Abstract

We present a listening grid for moral counseling, in which we pay particular attention, alongside the what, to how clients talk about themselves: as if they were spectators; aware what this talking does to them; how they perceive what is good from the past; and what they will strive for in the future. By this moral talk, clients discover a picture of the conviction that will enable them to make a decision.

Keywords: Contemplative listening, decision-making, ethics, existential decision, moral counseling, pastoral guiding

Introduction

In earlier publications, we have described moral counseling as a form of discussion support in which the primary focus is on issues (the what) raised by the client (De Groot & Leget, 2011). The strength of this technique is that it allows the client to consider the moral spectrum from different angles, assisted by a listening grid in which values and norms are interrelated, in order to arrive at a moral conviction.

In this article, we present a modified listening grid, in which we pay particular attention, alongside the what, to how clients talk about themselves. Do they talk as if they were spectators? Are they aware what this talking does to them? And, in the light of that experience, how do they perceive what is good from the past and what they will strive for in the future? By focusing on both the what and the how of this moral talk, clients discover a picture of the conviction that will enable them to make a decision.

Moral Counseling: A Method in Development

Moral counseling is defined as the professional support or supervision of clients when making decisions of which the outcome can be justified in moral terms, such as good, just or wise. Together with the client, the moral counselor examines what the moral problem is: does it involve a choice or a dilemma, or is there an unavoidable necessity to make a decision? This involves looking at what possible decision fits the “I” that must be rediscovered. Moral counseling can therefore definitely be recommended for clients who feel they have to make a decision that does not accord with their self-image – in short, if the decision to be taken propels them into a crisis situation.

The authors have considerable experience supervising clients faced with difficult healthcare choices: questions about life and death (e.g. abortion, euthanasia, and stopping treatment), questions about suitable intensive-care and neonatal treatment, and questions about organ donation (De Groot, 2016). But moral counseling can also be used outside the healthcare sector, for clients concerned about what is the moral course of action to take (prospective) and whether, seen from the present moment, their actions were the just ones (retrospective).

Our method is related to Carl Rogers’ discussion style (client-centered method) (Rogers & Dorfman, 1951; Rogers, 1966). Rogers’ primary focus is the counselor’s stance (realness, acceptance and respect, and empathic understanding) (Rogers & Freiberg, 1969). What this means for actual interventions by counselors became clear to us when we began using William Stiles’ taxonomy (Stiles, 1992) to analyze those interventions. For the discussion content, we used concepts from the work of Paul Ricoeur (Ricoeur, 1992). With these concepts, the focus was on the content of the client’s statements, the what. By reflecting on our courses and counseling practice, we have gained new insights, which Hans Evers describes elsewhere as contemplative listening. Using ideas from this approach, we look at how clients talk about themselves. Following Evers’ example, we have chosen below to use the terms “contemplative listening in moral issues”, and “auditor” rather than “counselor”.

Rogers and Stiles: From Tracking to Providing Space

Working in accordance with the method outlined, material was collected in an open, associative interview (Maso & Smaling, 1998), in which facts, emotions, attitudes and convictions could be addressed. The principles of client-centered therapy (the therapist’s congruence or genuineness, unconditional positive regard, a complete acceptance, and a sensitively accurate empathic understanding) were applied (Rogers, 1966). Initially, we found all interventions effective provided they were of a “tracking” nature. We started by using Stiles to analyze our discussions (Stiles, 1992). His definitions of the different interventions helped us gain a better understanding of the process by which people arrive at their convictions. Stiles also draws attention to the intent of an intervention. For example, a question can arise out of curiosity or judgment on the part of the auditor (QQ) , but also from the client’s need to check whether the reflection provided is correct. In the first instance, the discussion agenda is taken over by the auditor, rather than giving the client space to arrive at their own conviction. This led to a different view of the desired interventions. “Allowing space” became the key issue, rather than “tracking”. We opted for a radical application of the interview style that Stiles describes as “acquiescence”. Four interventions (Edification, Confirmation, Acknowledgment, and Reflection) demonstrate that the auditor is staying within the client’s frame of reference. Interventions such as Disclosure, Advisement, Question, and Interpretation should therefore be avoided. By being aware of their responses, auditors can ensure that they really are leaving the discussion agenda up to the client.

Ricoeur

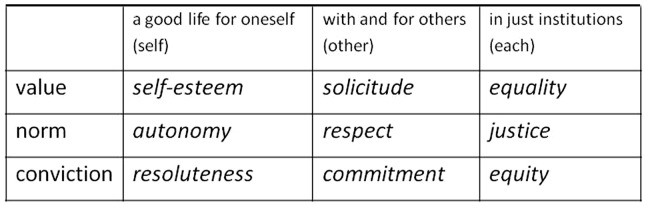

Once the client has been given every opportunity to make moral statements, the auditor and client will attempt to establish a coherent link between the statements. For this we used a listening grid with labels based on Ricoeur’s concepts (Ricoeur, 1992). The client and auditor are guided primarily by what the client has said. Ricoeur points out that when making a morally laden decision, people may justify their decision based on what they strive for in terms of values (ideal–teleological) or what they see as the norm for themselves (commandment, prohibition, and duty–deontological). For the first perspective, he draws on the ideas of Aristotle, and for the second on those of Kant. Ricoeur argues that both perspectives should be interrelated. He employs the image of a sieve. In order to come to a wise decision, Ricoeur explains, people need to pass what they label as “good” through the “sieve” of what they see as “just”. “Just” is about universal norms, norms that apply to everyone in all situations. Ricoeur advocates wisdom in a practical situation, a wisdom that is found by passing what you believe is worthwhile through the sieve of what is generally regarded as just.

Ricoeur also makes a distinction according to source of viewpoint: whether something comes from the individual themselves, from concern or respect for the (significant) other, or from emotions or rules of justice that are widely shared by society and all its institutions i.e. the anonymous other or “they”.

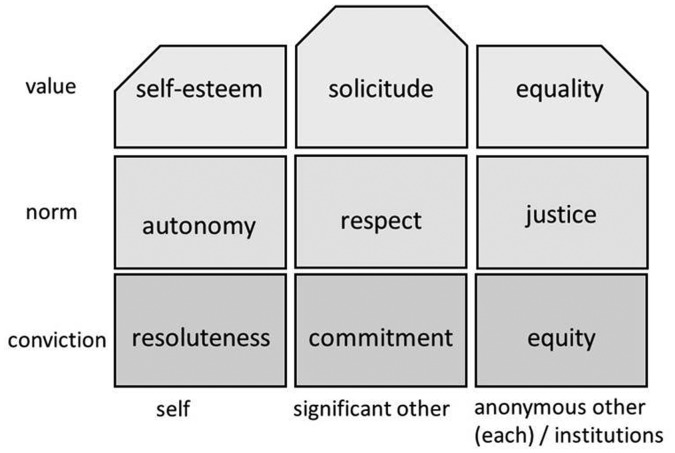

In our earliest publications (De Groot & Evers, 2007; De Groot & Leget, 2011), we presented several abstract terms that we took as labels from Ricoeur. Considerations that people use in order to arrive at a decision can always be traced back to one of these nine labels, which we have arranged in a listening grid (see the nine squares in diagram, Figure 1). In later publications (De Groot, 2008, 2011) we used the image of the moral house: people have everything “in-house” to justify their morally laden decisions. Their house accommodates values, norms and convictions which have their source in themselves, in their relationship with significant others or in social institutions that are just (see moral house, Figure 2). When making a decision, people intuitively open up some of the rooms. They will often have a preference for a particular “floor” or “story” of their moral house. Thus, whereas one person will tend to seek justification in certain values or ideals that they strive for, another will legitimize his or her decision by appealing to universal norms. Sometimes people will already have made a deliberation and will therefore speak with determination and conviction. In their discussion with the auditor, people are invited to examine every room of their moral house in order to see what they can contribute to their ultimate decision. Sometimes clients are confronted with “empty rooms” (e.g. no ideals of their own, or many norms), and they may become aware of these gaps. This can prompt them to supplement their spontaneous moral pronouncements. If clients feel that their moral considerations span the entire moral spectrum, they may decide which considerations weigh most heavily or which ones are in conflict. This gives rise in their mind to a “moral maps”, which they can then use to find their way through what was initially a bewildering tangle of thoughts and considerations.

Figure 1.

Ricoeur’s key concepts in regard to moral counselling.

Figure 2.

Ricoeur’s key concepts presented as a moral house.

Evers

The counseling discussion can be seen as an exchange of statements in which the content of the statements is paramount. In training situations and in our contact with clients, we have discovered that it is not only what clients say that matters, but also how clients talk about themselves. Talking can be viewed as the transmission of a message (content) by a person who is, but it can also be seen as a form of incarnation: a person becomes themselves while talking. Talking is therefore an act of creation, the person is engaged in self-realization. This calls for a particular kind of listening in order to bring the speaker to this self-realization. Hans Evers calls this “contemplative listening”: the auditor accompanies the client, who listens to themselves in order to seek a new self-understanding, a new conviction (Evers, 2017).

This form of contemplative listening can be used in moral counseling, which we have therefore renamed “contemplative listening in moral issues”. Whereas contemplative listening can relate to an entire life, with moral issues it is about the “moral life”, what Ricoeur called the “good life”. In this article, we follow Ricoeur in speaking about the “good life”. Clients give their opinions on the moral aspects of what they must decide. The moral (which we understand as a metaphor) is not something that can be encapsulated in one go, but a “picture of what is moral” arises when people talk about it from four different perspectives.

What is moral is revealed when people talk about their lives as though they were spectators. They talk about a range of facts with a moral dimension: the interests at stake, the usefulness of a particular decision, or effectiveness, efficiency and expediency. They survey the interests and factors that determine their room for maneuver because these are what conditions the moral decision. We call this perspective “overview”.

Talking involves not only an exchange of content, but also perception. This perception leads to a form of insight based on associations, emotions and behavior. Their insight tells clients something about how they relate to the act of speaking itself. They perceive that they can only achieve a “good life” within certain boundaries, by letting themselves be guided by certain norms and duties. The locus of morality is in their current emotions (Nussbaum, 2003). How people talk about themselves is determined not only by their spatial position in the present and their current talk within that (overview, and insight). Gauging the talk in the present vis-à-vis yesterday’s and tomorrow’s talk also determines the how – in other words, the temporal axis.

In seeking a “good life”, a client can report that value was always attached to a certain behavior in the past (retrospective). Clients then say what they until now have regarded as virtuous, as a good life. In the light of the dilemma they face, this is no longer self-evident.

Clients can also look ahead in time (prospective) and say, from the perspective of the present, what prospects there are of a good life in the future, as grounds for hope. These are the ideals and values at stake for them at that moment.

We find that this model, as an addition to Ricoeur, does justice not only to teleological and deontological viewpoints, but also to pragmatic and utilitarian considerations. The emphasis is not on providing a justification vis-à-vis the other, but on reorienting one’s own conviction. It is not about “sifting” or construing what is opportune within the justification, but about “discovering” the link that is already there. It is not about what is plausible, but about what is appropriate and authentic, an individual’s deepest conviction.

To illustrate our assumption that it is always possible to identify four perspectives in discourse, we cite several statements from a woman faced with the choice of whether or not to have an abortion. Her unborn child was given a negative diagnosis at the prenatal examination. The woman came to the auditor because she did not know what decision to make: to have an abortion or go ahead with the pregnancy and risk having a seriously disabled child. She made the following statements:

I have doubts about the self-evident nature of being a mother (insight–perception)

and I realize that I’ve always wanted children, without reservation (retrospective–conferring meaning)

and I think I’d be a good mother (prospective–ideal)

I already have a son (overview–fact)

and I also have to take him into account (insight–norm)

I was brought up to believe that you have to accept life as it comes (overview–fact)

and that’s why the idea of having an abortion makes me feel sick (insight–perception/boundary).

I think I have to be able to give my son all the time and care he needs (insight–norm)

My husband is opposed to us having this child (overview–interests).

Contemplative Listening in Moral Issues: Focus on the How and What

In our earliest publications on supporting clients in making a decision (De Groot & Leget, 2011), our focus was primarily on what clients talked about in relation to their choice of a good life. The schema that we derived from Ricoeur suggests a form of hierarchy: the “good life” is paramount but is corrected (using the analogy of the “sieve”) through normative ethics to arrive at wisdom in a specific situation. However, if we look at how people talk about themselves and their picture of a good life, we see that this hierarchy is absent. With our approach to a conviction based on four perspectives, we have shown that the picture of the conviction arises from these perspectives, which do not have a hierarchical relationship to one another.

Clients who come to an auditor face a choice that has caused them to feel confused. The solutions which, until now, they have applied to such choices no longer suffice. What they base their lives on and what they strive for as a “good life”, as they call it, have come under pressure. Yesterday’s convictions no longer provide grounds for today’s action: there are all manner of interests, as well as considerations of usefulness and necessity, which cause the individual and their world to change irreversibly. Clients feel that there are new boundaries to what is possible and to what they want. These limits trouble and confuse them: they have lost their conviction.

The Process of Contemplative Listening in Moral Issues

How can we support clients to make a choice or decision that they will not regret in the near future? The answer is: by supporting them in such a way that they arrive at a new conviction. In these cases, the auditor should focus on four elements. These are described using a case study, for which we present several illustrative excerpts. To avoid confusion in the description below, the male pronoun is used for the auditor and the female pronoun for the client.

| A chaplain (C) observes during a multidisciplinary conversation that that there is dissatisfaction among the nursing staff. Later, he asks Esther (E), the senior nurse, what is going on. She explains that a staff member from the department has been laid off because of cuts. Esther feels that it has not been handled in a satisfactory manner and wonders whether she should do something about it. She says it is not the first time that an older employee has lost their job because of cutbacks. The chaplain invites her (E) to come and discuss it calmly at a later time. |

Providing Space

When an auditor notices that a client is facing a moral dilemma, he can suggest contemplative listening in moral issues. The client states what the moral problem is and what decision she is intuitively inclining towards. She is then invited to explore her “moral map” by stating all the possible considerations that are relevant to her decision. The auditor maintains a low profile: he does not move outside the client’s frame of reference. The most common and effective intervention here is “Reflection” (Stiles, 1992), whereby the auditor “reflects” back what the client says. This usually takes the form of simply repeating, or summarizing using the auditor’s own words, what has just been said (e.g. C3). The auditor can also reflect on the discussion so far (a more complete summary, e.g. C4). This gives the client the space to talk about everything that occurs to her – in a more or less associative fashion – concerning what affects her most deeply. “Acknowledgment” is another suitable intervention. Small verbal and non-verbal encouragements can help the client to continue with her story (e.g. C2). During the discussion, the auditor takes notes for his own benefit of what is said. He may jot something down as a reminder of a particular statement. He may also make an audio recording of the discussion for later analysis.

| C1: | Esther, you told me what’s bothering you. |

| E1: | Yes, I have problems with how management is treating us. Staff here are simply discarded. Once again, an older colleague who I had a lot to do with has been sent packing. I don’t think it’s right, but I’m not doing anything about it. Should I? That might make me the focus of a lot of negative attention. |

| C2: | [nods] |

| E2: | She was put under pressure. She’s worked here, believe it or not, for 40 years! And now she’s simply been shoved out. I think it’s appalling. Should I just let it happen? |

| C3: | You think it’s appalling. |

| E3: | Yes, I do! That’s no way to treat people! I ask myself whether I should react if I see my employer doing things that I find appalling. |

| C4: | You have difficulty with the fact that a colleague who has worked here for 40 years has been laid off. You think it’s appalling. You want to say something but that would make you the focus of negative attention. |

All Perspectives

While exploring the moral map, the auditor should remember that the client can talk about herself from different perspectives. He should take this into account in his reflections, for example, by reflecting back both fact and perception (body language) (e.g. C11). It is then up to the client whether she addresses content (such as a factual matter) or focuses more on how talking about the content makes her feel. The auditor can also reflect two perspectives at the same time (such as ideal and interests, e.g. C13). Clients can change perspective very easily. By making good reflections, the auditor seeks to encourage the client to talk about considerations regarding her conviction from more than one perspective. There is no need, however, for the client to utilize all perspectives before arriving at a conviction. The client remains owner of the discussion and determines how she uses the space that is offered – the auditor does not need to “push and pull” the client.

| E10: | Hospital management thinks it’s okay to get rid of older people. But I think it’s not okay. Treating people like that is amoral. |

| C11: | You say amoral and you make a clear gesture with your arm. |

| E11: | It makes me angry! If nobody says anything, they’ll just think that it’s okay. It’s not okay, it’s appalling! |

| C12: | It makes you angry, it’s appalling. |

| E12: | Deep down, I have to say something, but what will happen to me if I do? I also have a family at home. But I can’t just sit back. |

| C13: | Deep in your heart you want to say something, but you’ve got a family too. |

| E13: | Yes, we’re breadwinners together, so I can’t just lose my job. And I worry that I’ll be next in line if I say something. It wouldn’t be the first time. |

Clarifying and Classifying the Moral Statements

In contemplative listening the auditor briefly records all relevant statements (facts, norms, virtues, and values) as if he were the secretary during the internal consultation. Once the topic has been examined from all sides and the client is not making any new statements, the client and auditor end the open discussion. The client has heard herself speak and has arrived at a new understanding of herself and her moral problem. New insights often emerge while speaking. The conviction or choice of direction may not yet be clear, however. To help the client to classify the many – sometimes contradictory – statements, the auditor and client look back at the statements that have been recorded. They now agree on a new direction for the discussion: once collected, the statements are formulated more specifically and then classified. The client is invited to formulate a statement she made during the discussion as a personal position (e.g. C101–103). For statements that are very general, the auditor encourages the client to make them more personal (e.g. C150–152). In the formulation, the auditor tries to pay attention not only to what is being said, but also how (from what perspective) it is being said. When the client says that a sentence truly reflects what she meant to say, that statement is recorded.

| C101: | Esther, you’ve made a number of statements. We’ll now write them down one by one. You said at the end of the discussion: “I want to be a big girl and say something about it.” Can you elaborate on that? |

| E101: | I think that I shouldn’t be afraid. I don’t want to be so afraid for my own job that I no longer protect the most vulnerable. Then I’d only be acting out of self-interest. |

| C102: | You don’t want to act out of self-interest, but instead stand up for the interests of others. |

| E102: | Exactly. If everyone only thought of themselves, that would be at the expense of the most vulnerable. I don’t want to be like that. |

| C103: | So, I’ll write down: “I want to stand up for the interests of the most vulnerable.” And also: “I don’t want to act out of self-interest.” |

| E103: | Not purely out of self-interest, no. |

| … | |

| C150: | And this statement from the beginning: “That’s no way to treat people.” |

| E150 | What management is doing isn’t just. You have to treat people with respect, you can’t just unceremoniously discard them. |

| C151 | Discard |

| E151 | If someone’s given her all for your hospital for 40 years, I think you should thank them for all that they’ve done and let them work in peace until they retire. It’s a question of respect and appreciation. |

| C152 | I’m writing down: “I believe you should treat people with respect and appreciation.” |

Once the statements have been recorded, the auditor asks the client to organize them by perspective. He asks her, in language she understands, what the differences in perspective are and how we can identify them as fact, norm and duty, virtue or ideal and value. A ranking can be made within the different perspectives: some values may be more important than others, some norms may weigh more heavily or be more binding than others, etc. Some things may also remain ambivalent.

| C201 | Esther, the statement “I want to stand up for the interests of the weakest” – is that something you have to do, something you would like to do or is it how you know yourself to be? |

| E202 | Well, I definitely don’t do it all the time, I try to do it more often. I’ve sometimes spoken out in the past, but it cost me dearly. So, it’s something that I’d like to do, but I don’t have to. |

| C202 | Is it your wish to act in such a way? |

| E202 | Yes. So that goes on the right with the ideals? |

| C203 | It’s up to you where you put it. You can always move it again. |

| E204 | With the ideals, then. |

| C205 | And how important is it to you? |

| E205 | Very important. So, put in the middle. |

A further distinction can be made with all four perspectives between what the client sees as coming from herself, what arises out of concern or respect for the significant other, or from the values and norms that she derives from certain institutions.

| C206 | Here I’ve got: “I’m a breadwinner, I have to keep my job.” Where would you put that? |

| E206 | Well, I don’t want to lose my job, otherwise I would have said something long ago and looked for other work. I have to keep this job in the interests of my family. Isn’t that a fact that I have to take into account? Weren’t interests at the top? |

| C207 | And are they your own interests, those of a significant other or of “them”? |

| E207 | My family, so in the middle square. And that’s very important, but also not so bad. As a mother, I’d rather set a good example than be afraid to open my mouth at work. |

However, Ricoeur’s distinction between self, significant other and anonymous other (“they”) can also be left out if there is not enough time available for ample consideration. In that case, the approach from four perspectives will suffice. The client takes the lead in classifying the statements. If she regards a particular statement as a norm or bottom line for herself, the auditor must go along with that, even if, based on his own frame of reference, he views the statement more as a virtue or value.

The Client Decides

Once all statements have been identified, the auditor asks finally: what do you see? If you cast your eye over all of this, is there a picture (of the good life), a sentence or saying that occurs to you? Here, the auditor asks about the “picture” of a new conviction.

To conclude the discussion, the auditor can ask how this picture relates to the client’s initial intuitions. Sometimes the discussion prompts the client to modify her earlier intuition or tie it to a different decision. For example, in various cases involving pregnant women, we have heard: “I’m opting for an abortion now, but I don’t ever want to be faced with this decision again.” For one woman, this meant deciding to never become pregnant again. For another, it meant that she did not want to undergo prenatal diagnostic testing during any subsequent pregnancy. In the case study presented here, this exercise uses arguments to reinforce the intuition articulated earlier, so that the client is more confident about her decision.

| E301 | Gosh, I thought I was doing the just thing by keeping my mouth shut. But in fact, I’ve known for a long time that I wanted to say something. It’s just that I was so scared about my job. But now I feel that I simply can’t ignore this injustice. Also, because otherwise, management would simply keep treating us this way. I can’t keep going on acting as though nothing has happened. |

Rounding Off the Discussion

The client goes home with a picture of a new conviction. It is not necessarily clear as yet what decision she will tie it to. The auditor has to curb his curiosity and not insist that the client make a decision in his presence. It is usually enough to express confidence in the client that she can make the decision herself. The client makes the decision with respect to herself. The auditor can only confirm that, however the decision turns out, the client knows for herself that she arrived at it after careful consideration. That knowledge may be comforting, even if the client later regrets her decision. What gives comfort is the conviction that she made a moral decision in that particular situation: “Here I stand, I can’t act in any other way”. The auditor does not take leave of the client until he has once again assured her that the privacy of this discussion will be respected and that he will never call her to account for her decision. He advises the client to go home and sleep on it for a night.

Table 1.

Casus.

| A chaplain (C) observes during a multidisciplinary conversation that that there is dissatisfaction among the nursing staff. Later, he asks Esther (E), the senior nurse, what is going on. She explains that a staff member from the department has been laid off because of cuts Esther feels that it hasn’t been handled in a satisfactory manner and wonders whether she should do something about it. She says it is not the first time that an older employee has lost their job because of cutbacks. The chaplain invites her (E) to come and discuss it calmly at a later time. |

Table 2.

Casus (continued).

| C1: | Esther, you told me what’s bothering you. |

| E1: | Yes, I have problems with how management is treating us. Staff here are simply discarded. Once again, an older colleague who I had a lot to do with has been sent packing. I don’t think it’s right, but I’m not doing anything about it. Should I? That might make me the focus of a lot of negative attention. |

| C2: | [nods] |

| E2: | She was put under pressure. She’s worked here, believe it or not, for 40 years! And now she’s simply been shoved out. I think it’s appalling. Should I just let it happen? |

| C3: | You think it’s appalling. |

| E3: | Yes, I do! That’s no way to treat people! I ask myself whether I should react if I see my employer doing things that I find appalling. |

| C4: | You have difficulty with the fact that a colleague who has worked here for 40 years has been laid off. You think it’s appalling. You want to say something but that would make you the focus of negative attention. |

Table 3.

Casus (continued).

| E10: | Hospital management thinks it’s okay to get rid of older people. But I think it’s not okay. Treating people like that is amoral. |

| C11: | You say amoral and you make a clear gesture with your arm. |

| E11: | It makes me angry! If nobody says anything, they’ll just think that it’s okay. It’s not okay, it’s appalling! |

| C12: | It makes you angry, it’s appalling. |

| E12: | Deep down, I have to say something, but what will happen to me if I do? I also have a family at home. But I can’t just sit back. |

| C13: | Deep in your heart you want to say something, but you’ve got a family too. |

| E13: | Yes, we’re breadwinners together, so I can’t just lose my job. And I worry that I’ll be next in line if I say something. It wouldn’t be the first time. |

Table 4.

Casus (continued).

| C101: | Esther, you’ve made a number of statements. We’ll now write them down one by one. You said at the end of the discussion: “I want to be a big girl and say something about it.” Can you elaborate on that? |

| E101: | I think that I shouldn’t be afraid. I don’t want to be so afraid for my own job that I no longer protect the most vulnerable. Then I’d only be acting out of self-interest. |

| C102: | You don’t want to act out of self-interest, but instead stand up for the interests of others. |

| E102: | Exactly. If everyone only thought of themselves, that would be at the expense of the most vulnerable. I don’t want to be like that. |

| C103: | So, I’ll write down: “I want to stand up for the interests of the most vulnerable.” And also: “I don’t want to act out of self-interest.” |

| E103: | Not purely out of self-interest, no. |

| … | |

| C150: | And this statement from the beginning: “That’s no way to treat people.” |

| E150 | What management is doing isn’t just. You have to treat people with respect, you can’t just unceremoniously discard them. |

| C151 | Discard |

| E151 | If someone’s given her all for your hospital for 40 years, I think you should thank them for all that they’ve done and let them work in peace until they retire. It’s a question of respect and appreciation. |

| C152 | I’m writing down: “I believe you should treat people with respect and appreciation.” |

Table 5.

Casus (continued).

| C201 | Esther, the statement “I want to stand up for the interests of the weakest” – is that something you have to do, something you would like to do or is it how you know yourself to be? |

| E202 | Well, I definitely don’t do it all the time, I try to do it more often. I’ve sometimes spoken out in the past, but it cost me dearly. So, it’s something that I’d like to do, but I don’t have to. |

| C202 | Is it your wish to act in such a way? |

| E202 | Yes. So that goes on the right with the ideals? |

| C203 | It’s up to you where you put it. You can always move it again. |

| E204 | With the ideals, then. |

| C205 | And how important is it to you? |

| E205 | Very important. So, put in the middle. |

Table 6.

Casus (continued).

| C206 | Here I’ve got: “I’m a breadwinner, I have to keep my job.” Where would you put that? |

| E206 | Well, I don’t want to lose my job, otherwise I would have said something long ago and looked for other work. I have to keep this job in the interests of my family.Isn’t that a fact that I have to take into account? Weren’t interests at the top? |

| C207 | And are they your own interests, those of a significant other or of “them”? |

| E207 | My family, so in the middle square. And that’s very important, but also not so bad. As a mother, I’d rather set a good example than be afraid to open my mouth at work. |

Table 7.

Casus (continued; end).

| E301 | Gosh, I thought I was doing the just thing by keeping my mouth shut. But in fact, I’ve known for a long time that I wanted to say something. It’s just that I was so scared about my job. But now I feel that I simply can’t ignore this injustice. Also, because otherwise, management would simply keep treating us this way. I can’t keep going on acting as though nothing has happened. |

Looking Back

In this article, we have attempted to record our latest experiences and insights about what we earlier labeled “moral counseling”. One insight is that “contemplative listening in moral issues” would be a more appropriate term. We have described the development of the model using our own experiences and reflections. We believe that the model is theoretically sound and that it has been tested in practice. This article does not seek to be a manual for contemplative listening in moral issues. In our view, this form of listening cannot simply be learned from a book, but requires a good deal of practice and in particular, learning from feedback. The over 100 course participants who we have taught the basic skills of contemplative listening in moral issues over the past ten years will confirm this. We are also grateful to them for their feedback. Without them, this article could not have been written.

Acknowledgments

We are particularly grateful to Hans Evers for the rationale behind our discussion method. We would also like to thank him for his critical comments on our manuscript and his contribution to developing our training courses. Furthermore, we wish to thank Radboud in’to Languages for translating the article and their editorial suggestions.

Biography

Jack de Groot, PhD, is emeritus hospital chaplain (BCC), pastoral supervisor in CPE-courses, trainer in moral counseling and moral casedeliberation. He is also an ethicist and did research about decision making by relatives in the context of postmortal organ donation.

Maria E.C. van Hoek, MSc, is co-trainer in moral counseling and moral case deliberation. She studied Biomedical Sciences and did research on various medical ethical issues.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Evers, H. (2017). Contemplative listening. A rhetorical-critical approach to facilitate internal dialogue. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- De Groot J. (2008) Morele counseling voor de patiënt als pendant voor moreel beraad [Moral counseling for the patient as a counterpart for moral case deliberation]. Tijdschrift voor Gezondheidszorg & Ethiek 18: 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot J. (2011) Ethische benadering – Nijmeegse methode voor morele counseling [Ethical approach – Nijmegen method for moral counseling]. Handelingen, Tijdschrift voor Praktische Theologie en Religiewetenschap 38(3): 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, J. (2016). Decision making by relatives of eligible brain dead organ donors. PhD Thesis, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

- De Groot J., Evers H. (2007) Morele counseling: Presentatie van de Nijmeegse methode [Moral counseling: Presentation of the Nijmegen method]. Praktische Theologie 34: 314–332. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot J., Leget C. (2011) Moral counselling: A method in development. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling 65(1–2): 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maso, I., & Smaling, A. (1998). Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktijk en theorie [Qualitative research: Theory and practice]. Meppel, The Netherlands: Boom Koninklijke Uitgevers. [In Dutch.].

- Nussbaum M. C. (2003) Upheavals of thought: The intelligence of emotions, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ricoeur P. (1992) Oneself as another, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, C. R. (1966). Client-centered therapy. In S. Arieti (Ed.), American handbook of psychiatry (Vol. 3, pp. 183–200). New York, NY; London, UK: Basic Books, Inc., Publishers.

- Rogers C. R., Dorfman E. (1951) Client-centered: Its current practice, implications, and theory, Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers C. R., Freiberg H. J. (1969) Freedom to learn, Columbus, OH: Merrill. [Google Scholar]

- Stiles W. B. (1992) Describing talk: A taxonomy of verbal response modes, Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]