Abstract

Objectives:

While topical corticosteroids are first-line therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), the data regarding long-term effectiveness are lacking. We aimed to determine long-term histologic and endoscopic outcomes of maintenance therapy in EoE steroid responders.

Methods:

We performed a retrospective study of adults with EoE at UNC Hospitals who had initial histologic response (<15 eos/hpf) after 8 weeks of topical steroids, and maintained on therapy. Endoscopic and the histologic data were recorded at baseline and follow-up endoscopies. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to assess loss of treatment response by steroid dose at recurrence, and Kaplan–Meier analysis to calculate durability of disease remission.

Results:

Of 55 EoE patients with initial response to swallowed/topical fluticasone or budesonide over a median 11.7 months, 33 had at least two follow-up EGDs. Of these patients, 61% had histologic loss of response and worse endoscopic findings. There was no difference in baseline steroid dose (P=0.55) between the groups, but those maintained on their initial dose had lower odds (OR: 0.10; 95% CI: 0.01, 0.90) of loss of response compared to those who had subsequent dose reduction. On survival analysis, 50% had loss of response to steroids by 18.5 months and 75% by 29.6 months.

Conclusions:

In adult EoE steroid responders, loss of treatment response is common, and is associated with a steroid dose reduction. Routinely lowering doses for maintenance steroids may provide inferior outcomes.

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune-mediated condition characterized by eosinophilic infiltration of the esophageal mucosa, leading to symptoms of esophageal dysfunction.1, 2 Current guidelines3 recommend that the first-line pharmacologic treatment for EoE should be swallowed, or topical, corticosteroids such as budesonide or fluticasone. While there are some patients with a severe fibrostenotic phenotype who may not respond very well to these medications,4, 5 most studies show initial histologic response rates ranging from 50% to >90%.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 The preliminary data have also shown that controlling inflammation with topical corticosteroids can decrease the need for future dilations.15, 16 As a result, topical corticosteroids are now commonly used for the management of EoE for both inflammatory and fibrostenotic phenotypes.

After an initial treatment course, there is controversy about whether all patients with EoE need to be maintained indefinitely on topical steroids for disease control.3, 17 This is because existing studies on the long-term outcomes of corticosteroid treatment in adult EoE patients are limited.5, 9, 18, 19 While these data consistently show nearly universal recurrent disease after discontinuation of initial treatment,5, 20 the long-term efficacy, durability, and safety of maintenance steroid treatment is not well understood. In addition, factors such as treatment duration after initial response as well as the ideal maintenance dose of steroids are not currently elucidated.

The aims of this study were to determine long-term histologic and endoscopic outcomes, and durability of response of maintenance topical corticosteroid treatment in EoE patients who achieved an initial histologic response after an 8-week course of topical corticosteroids. In addition, we aimed to explore the impact of topical steroid dose and type on the durability of ongoing histologic response.

Methods

Study design and data source

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of EoE patients at the University of North Carolina (UNC) Hospitals from 2006–2015 using the UNC EoE Clinicopathologic database. The database contains EoE patients of all ages who met consensus guidelines1, 2, 3 for a new diagnosis of EoE, including symptoms of esophageal dysfunction, ≥15 eosinophils per high-power field (eos/hpf) (hpf area=0.24 mm2), non-response to a high-dose proton-pump inhibitor trial, and exclusion of competing causes. The details of this database have been described previously.4, 21, 22, 23

Study population, procedures, treatments, and follow-up

All patients underwent a baseline endoscopy where EoE was diagnosed. For this procedure, endoscopic findings were noted and esophageal biopsies were obtained. The peak eosinophil counts (eos/hpf) were determined from esophageal biopsies as per clinical protocol. Patients with PPI responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE) were excluded, so the cases are a PPI-non-responsive EoE group. Following this, per clinical protocol at our institution, patients were placed on either budesonide (0.5–1 mg twice daily, based on patient age, with the aqueous formula mixed into a slurry with 5 g of sucralose)8, 24 or fluticasone (440–880 mcg twice daily, based on patient age).6 After an 8-week course of topical corticosteroid treatment, patients underwent a repeat upper endoscopy with documentation of endoscopic and histologic findings. Histologic responders were defined as patients with <15 eos/hpf and non-responders as those with ≥15 eos/hpf.25 The prior published data from our cohort showed initial histologic response in 57% of incident EoE cases who received topical corticosteroids.26 After this initial treatment course, patients continued to be treated on a clinical basis, and topical steroid dose, type, and dose adjustments were at the discretion and instruction of the individual provider.

For this study, we only included adults ≥18 years of age meeting EoE consensus guidelines who had an initial histologic response (<15 eos/hpf) after an 8-week course of topical corticosteroids (fluticasone or budesonide), and who were subsequently maintained on steroid therapy for ≥75% of the follow-up time. We determined this level of maintenance by reviewing the electronic medical record for prescriptions provided as well as clinic or endoscopy follow-up, which included routine documentation of ongoing use and compliance with the medication. Follow-up time was defined as time from baseline endoscopy to the time of histologic loss of response (defined as ≥15 eos/hpf) or to the end of the data collection period. Endoscopic and the histologic data from any upper endoscopy performed during the follow-up period were collected. The endoscopic data included the presence of edema, rings, exudates, furrows, or strictures. Since some included the data pre-dating the EREFS scoring system,27 a simplified endoscopic severity score (ESS) was used with each EREFS finding (edema, rings, exudates, furrows, and strictures) scored as absent or present (score range: 0–5). The presence of candida and whether dilation was performed at that endoscopy was also obtained. The histologic data comprised of maximum eosinophil counts (eos/hpf).

At each endoscopy, the use and dose of proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) or topical corticosteroids were noted. PPI dose was categorized as high (twice a day), low (daily), or none. For corticosteroids, the type (budesonide or fluticasone) and total daily dose at each follow-up endoscopy were documented. Detailed chart review was performed to determine the exact start and stop dates for each course of corticosteroid treatment. Any change in steroid dosing during the follow-up period was directed by the clinical provider. Participants who were enrolled in clinical trials for topical corticosteroids or other alternate EoE therapies were excluded, as were patients undergoing dietary elimination therapy.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed at both the patient and endoscopy level. For the per-patient analysis, only the data up to the first episode of loss of steroid response or to the end of the follow-up period in those with sustained steroid response were included. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline patient characteristics. Bivariate analyses were performed to determine the relationship between each independent variable and steroid response, using Student’s t-test and Wilcoxon rank-sum for continuous variables and Pearson’s χ2 tests for categorical variables. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to calculate odds of loss of response to steroid treatment based on steroid dose at the time of recurrence, adjusted for steroid type, history of dilation, and follow-up time. For this analysis, steroid dose was dichotomized into a high (daily >1000 mcg of budesonide or >880 mcg of fluticasone) or low (daily ≤1000 budesonide or ≤880 mcg of fluticasone) dose category.

For the per-endoscopy analysis, follow-up upper endoscopies were categorized into time periods from baseline endoscopy: ≤3, 3–12, 12–24, >24 months, in order to compare results to the previously reported data.18, 19 For each time period, we determined the mean ESS, maximum eosinophil count, mean steroid dose, and proportion of patients using a PPI. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to calculate the durability of topical corticosteroids in maintaining histologic remission.

For the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, repeated measures for each patient were allowed and patients were not censored at the time of first loss of response, as in the per-patient analysis. Therefore, the entire time under observation for each patient was incorporated and some patients may have had recurrent loss of treatment response. All analyses were performed using Stata 13 (College Station, TX, USA). The study was approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board.

Results

Patient characteristics

There were 55 patients who met the inclusion criteria (Table 1). Mean age was 39.9±11.9 years, 67% were men, and 96% were white. Most common presenting symptoms were dysphagia (93%), food impaction (49%), and heartburn (42%). Most common baseline endoscopic findings were esophageal rings (84%), furrows (73%), and plaques (44%). Mean baseline eosinophil count was 69.7±71.1 eos/hpf. More than half of the sample had a history of dilation, 75% were treated with budesonide, and 25% with fluticasone. The median follow-up time was 11.7 months.

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

| Steroid responders (n=55) | |

|---|---|

| Age, y, mean±s.d. | 39.9±11.9 |

| Male, n (%) | 37 (67) |

| White, n (%) | 52 (96) |

| Symptoms (n, %) | |

| Dysphagia | 51 (93) |

| Food impaction | 27 (49) |

| Chest pain | 11 (20) |

| Heartburn | 23 (42) |

| Abdominal pain | 6 (11) |

| Nausea | 2 (4) |

| Vomiting | 10 (18) |

| Failure to thrive | 1 (2) |

| Symptom duration before diagnosis, y, mean±s.d. | 10.5±9.1 |

| Atopic disease (n, %) | 27 (49) |

| Allergic Rhinosinusitis (n, %) | 35 (66) |

| Asthma (n, %) | 11 (20) |

| Food allergy (n, %) | 18 (35) |

| Baseline endoscopic findings (n, %) | |

| Rings | 46 (84) |

| Linear furrows | 40 (73) |

| White plaques | 24 (44) |

| Decreased vascularity | 14 (25) |

| Crêpe-paper mucosa | 0 (0) |

| Strictures | 18 (33) |

| History of dilation (n, %) | 31 (56) |

| Baseline eosinophil count, eos/hpf, mean±s.d. | 69.7±71.1 |

| Steroid type, n (%) | |

| Budesonide | 41 (75) |

| Fluticasone | 14 (25) |

| Follow-up time, months, median (IQR) | 11.7 (3.7–24.2) |

Results from per-patient analysis

Out of the 55 patients, 33 had at least two subsequent endoscopies after the baseline exam and were included in the per-patient analysis (Table 2). The two subsequent endoscopies consisted of one showing initial response post-treatment and one assessing the effect of maintenance therapy). Out of the 33 patients, 61% (n=20) had histologic loss of response to treatment and 39% (n=13) maintained histologic response. There were no differences in gender, race, symptom duration, or follow-up time between those with loss of response and ongoing response to topical corticosteroid therapy. Similarly, there was no difference between the groups in endoscopic severity score (ESS) and number of eosinophils at baseline or after 8 weeks of topical corticosteroid therapy. As expected, the group with loss of response had a higher ESS score and higher peak eosinophil count compared to the group with ongoing response. Indications for follow-up EGD after initial response during the maintenance period included surveillance EGD to assess for ongoing maintenance steroid response (n=21; 64%) or for recurrent symptoms such as dysphagia (n=9; 27%), heartburn (n=2; 6%), or abdominal pain (n=1; 3%).

Table 2. Characteristics of participants with ongoing response and loss of response following successful histologic response to steroid therapy.

| Loss of responsea (n=20) | Ongoing response (n=13) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean±s.d. | 37.75±10.15 | 40.41±9.33 | 0.45 |

| Male, n (%) | 12 (60) | 8 (62) | 0.93 |

| White, n (%) | 19 (95) | 13 (100) | 0.41 |

| Symptom duration before diagnosis, y, median (IQR) | 8 (2–20) | 10.5 (4.5–17.5) | 0.54 |

| Endoscopic Severity Score (ESS), median (IQR) | |||

| Baseline | 4 (2–5) | 3 (2–3) | 0.07 |

| Post-steroid | 1 (1–1.5) | 2 (1–2) | 0.15 |

| At recurrence or end of follow-up | 3 (1.5–4) | 1 (1–2) | 0.02 |

| Eosinophil count, eos/hpf, median (IQR) | |||

| Baseline | 47 (28–88) | 50 (25–60) | 0.59 |

| Post-steroid | 0 (0–3) | 0 (0–2) | 0.90 |

| At recurrence or end of follow-up | 63 (28–95) | 1 (1–5) | <0.01 |

| Steroid type, n (%) | 0.02 | ||

| Budesonide | 18 (90) | 7 (54) | |

| Fluticasone | 2 (10) | 6 (46) | |

| Daily steroid dose, mg, mean±s.d. (initial) | |||

| Budesonide | 2018±1070 | 2286±756 | 0.55 |

| Fluticasone | 1760±0 | 1760±0 | n/a |

| Daily steroid dose, mg, mean±s.d. (at recurrence or end of follow-up) | |||

| Budesonide | 708±643 | 1429±732 | 0.02 |

| Fluticasone | 440±622 | 733±585 | 0.57 |

| Follow-up time, months, median (IQR) | 27 (15–39) | 17 (11–24) | 0.22 |

| Candida, n (%) | 1 (5) | 1 (8) | 0.75 |

n=33 as the data restricted to patients who had at least two subsequent endoscopies after baseline exam.

≥15eos/hpf on histology.

While both groups were treated with comparable steroid doses at baseline (P=0.55), those who had loss of treatment response were on a significantly lower dose of budesonide at the time of disease recurrence compared to those with ongoing response (708 vs 1429 mcg, P=0.02). While the dose of fluticasone was also lower in those with histologic recurrence, this was not statistically significant (440 vs 733 mcg, P=0.57). The significant difference in steroid dose at the time of recurrence or end of follow-up period for ongoing responders persisted on multivariable logistic regression adjusted for steroid type, history of dilation, and follow-up time. After initial histologic response to topical corticosteroid therapy, those patients who were maintained on a higher dose (daily >1000 mcg of budesonide or >880 mcg of fluticasone) had lower odds of loss of treatment response (OR: 0.10; 95% CI: 0.01, 0.90) compared to the patients whose initial steroid dose was reduced (daily ≤1000 budesonide or ≤880 mcg of fluticasone).

Results from per-endoscopy analysis

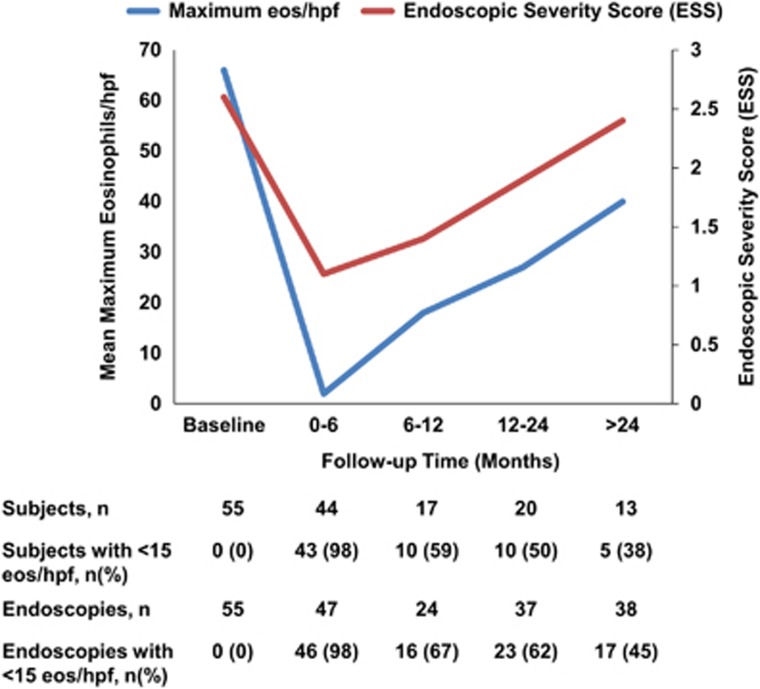

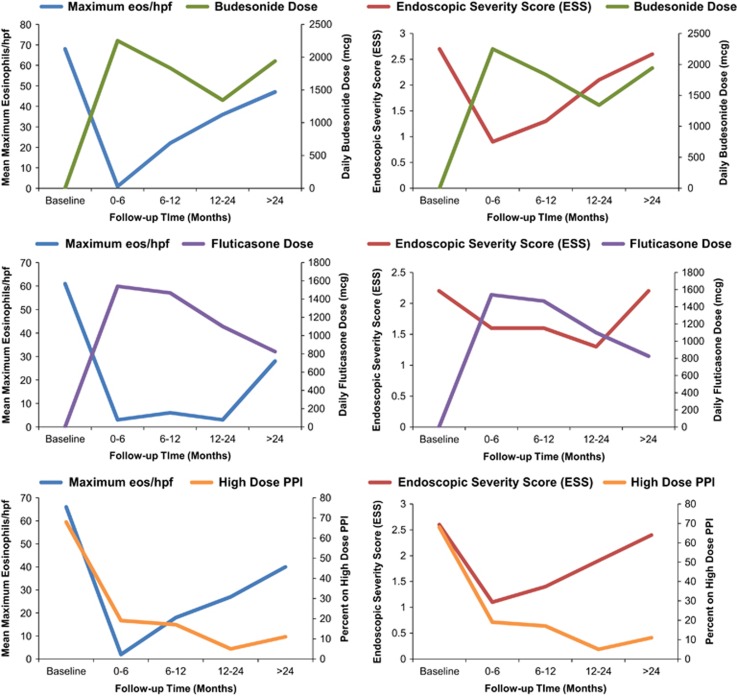

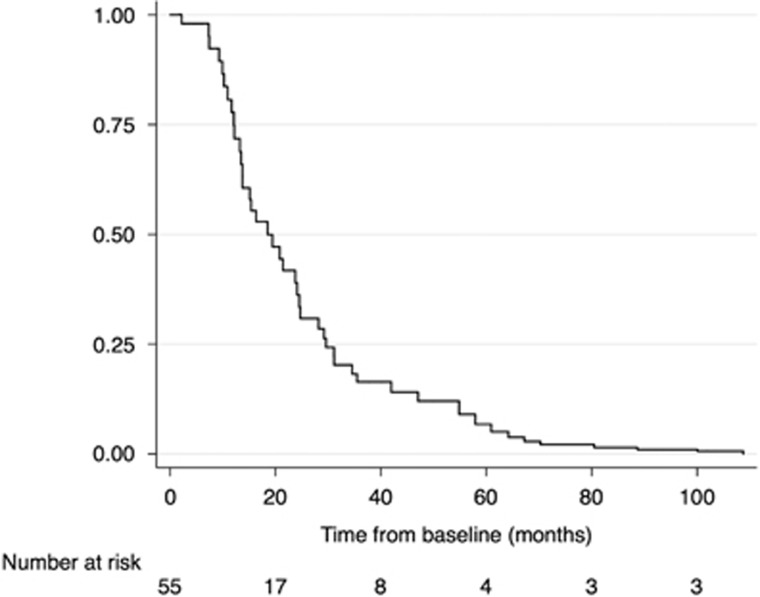

There were a total of 184 endoscopic exams that were included (Table 3). Peak eosinophil counts and ESS scores were lowest within the first 6 months and increased subsequently during the follow-up period (Figure 1). When the ESS and eosinophil count at each follow-up time point was assessed in relation to topical corticosteroid dose, there was an increase in ESS and peak eos/hpf after 6 months from baseline exam that correlated with decrease in budesonide dose (Figure 2). Notably, the response did not improve with subsequent increase of budesonide dose. For those on fluticasone, a similar trend of loss of response was seen, but after 12 months compared to 6 months with budesonide, and the increase in ESS and eosinophil counts also correlated with a drop in steroid dose. On Kaplan–Meier analysis, half the patients had loss of response to topical corticosteroid therapy by 18.5 months and 75% of the sample has loss of treatment response by 29.6 months (Figure 3).

Table 3. Endoscopic findings, eosinophil count, and mean steroid dose at follow-up time periodsa from baseline endoscopy.

| Baseline | 0–6 months | 6–12 months | 12–24 months | >24 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endoscopies, n (%) | 55 (30) | 30 (16) | 24 (13) | 37 (20) | 38 (21) |

| Maximum eos/hpf, mean±s.d. | 66±62 | 2±4 | 18±29 | 27±42 | 40±59 |

| Endoscopic findings, n (%) | |||||

| Edema | 14 (26) | 4 (9) | 2 (8) | 7 (19) | 14 (37) |

| Rings | 44 (81) | 27 (57) | 15 (63) | 25 (68) | 27 (71) |

| Exudates | 23 (43) | 2 (4) | 2 (8) | 7 (24) | 17 (45) |

| Furrows | 38 (70) | 8 (17) | 6 (25) | 17 (46) | 19 (50) |

| Strictures | 20 (36) | 9 (19) | 8 (33) | 12 (32) | 15 (39) |

| Endoscopic severity score (ESS)b, mean±s.d. | 2.6±1.4 | 1.1±1 | 1.4±0.9 | 1.9±1.3 | 2.4±1.5 |

| Mean steroid dose, mcg, mean±s.d. | |||||

| Budesonide | 0±0 | 2250±920 | 1833±794 | 1344±1172 | 1941±1130 |

| Fluticasone | 0±0 | 1540±407 | 1467±454 | 1100±660 | 825±367 |

| PPI, n (%) | |||||

| Highc | 36 (68) | 9 (19) | 4 (17) | 2 (5) | 4 (11) |

| Lowd | 7 (13) | 26 (55) | 11 (48) | 11 (30) | 11 (29) |

| None | 10 (19) | 12 (26) | 8 (35) | 24 (65) | 23 (61) |

The data from per-endoscopy analysis so each patient may be represented more than once during a specific follow-up interval.

Each EREFS finding (edema, rings, exudates, furrows and strictures) scored as absent or present (score range: 0–5).

PPI dosed twice a day

PPI dosed daily.

Figure 1.

Mean maximum eosinophil count and Endoscopic Severity Scores (ESS) at baseline and follow-up time periods in adult EoE patients treated with topical steroid treatment. Each EREFS finding (edema, rings, exudates, furrows and strictures) scored as absent or present for ESS score (range: 0–5). The data is from per-endoscopy analysis so each patient may be represented more than once during a specific follow-up interval.

Figure 2.

Mean maximum eosinophil count (eos/hpf) and endoscopic severity scores (ESS) at baseline and follow-up time periods by steroid type and use of high dose of proton-pump inhibitor (PPI). Each EREFS finding (edema, rings, exudates, furrows and strictures) scored as absent or present for ESS score (range: 0–5). The data is from per-endoscopy analysis so each patient may be represented more than once during a specific follow-up interval. High-dose PPI defined as twice a day dosing.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve for ongoing histologic response (<15 eos/hpf) for EoE patients maintained on topical corticosteroid treatment after initial histologic response.

Discussion

Topical corticosteroids are the first-line pharmacologic treatment for EoE, and after an initial treatment course, they are frequently used for maintenance therapy.17 However, our knowledge of the best long-term management of patients with initial response to steroid therapy is hobbled by a relative paucity of the long-term follow-up data on this approach. In this study of adult EoE patients who initially had a histologic response and subsequent maintenance of topical corticosteroid therapy with fluticasone or budesonide, 61% had histologic loss of response to treatment over a median follow-up time of 11.7 months, with associated worsening of endoscopic findings. There were no significant baseline differences in eosinophil count, endoscopic severity score (ESS), and steroid dose or type that predicted this loss of treatment response. However, there was an association with steroid dose at the time of histologic recurrence. Patients who were maintained on a high (daily >1000 mcg of budesonide or >880 mcg of fluticasone) steroid dose had lower odds of loss of response compared to those who had a decrease in steroid dose (daily ≤1000 budesonide or ≤880 mcg of fluticasone) after achieving initial histologic response. This finding is notable as it challenges the hypothesis that once histologic remission is achieved with topical steroids, the medications can be continued long-term without a detriment in efficacy. Additionally, our finding that recurrence appears to be dose dependent, and that re-increasing the dose may not lead to histologic improvement is also an important observation, potentially challenging whether decreasing the dose is appropriate clinically.

These data augment a sparse literature on the long-term outcomes of maintenance topical corticosteroid therapy in EoE, particularly in adults. In one prospective cohort of pediatric EoE patients,18 swallowed fluticasone was shown to be effective in maintaining symptom, endoscopic, and histologic features over a follow-up period of 2 years. However, in this study, patients were maintained on the same dose of fluticasone during the entire follow-up period and thus may have had more successful ongoing treatment response. Even in this study, with its standardized high dose of steroids, by two years of follow-up eosinophil counts were noted to increase above the level seen after the initial response. This deterioration of histological effect is consistent with our data. A similar trend was noted in a separate retrospective pediatric cohort study.19 In a randomized multicenter trial9 of patients of all ages, daily treatment with 1760 mcg of swallowed fluticasone resulted in histologic remission in 65–77% of the patients after 3 months. Of the 15 patients that had initial histologic response, the dose of fluticasone was reduced to 880 mcg after 3 months. Interestingly, a large proportion of this maintenance group (27%) lost response in the subsequent 3 months. The only RCT in adults to assess maintenance treatment in patients who initially responded to swallowed budesonide randomized the patients to a maintenance dose of 0.5 mg daily or to placebo for a year.5 In the treatment arm (n=14), the eosinophil load increased from 0.4 to 31.8 eos/hpf, and only 36% maintained a remission of 5 eos/hpf, indicating that this dose was likely too low for long-term use. However, doses of budesonide in our study were higher than this, and we still had a similar rate of loss of histologic response.

Perhaps the most comparable study is a recent open-label extension of a double-blind randomized controlled trial of budesonide oral suspension.28 In this study, of adolescents and adults initially treated with the medication at 2 mg twice daily, 47% of the initial histologic responders were able to maintain response, and non-response was most frequent in those patients who decreased to 2 mg once daily dosing. This is consistent with our finding that the loss of response in EoE patients who initially responded to topical corticosteroids correlated with dose reduction, especially for budesonide. In our practice, the general approach is to use the lowest topical steroid dose for maintenance that continues to achieve histologic and clinical remission, and we typically reduce the steroid dose by half in patients who show initial histologic response. The results of this study suggest that a dose reduction in steroid responding EoE patients may result in a higher risk of disease relapse, and patients do not always re-achieve remission. The data also raise the question of whether “steroid resistance” may develop over time, which is seen in other conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).29 However, more investigation would be needed to determine if this phenomenon of steroid resistance exists in EoE, and if it does, what the mechanism would be.

Our study is limited by the retrospective design, and the study population is from a single-center tertiary care referral center, which can limit generalizability. Because patients were treated and followed per clinical protocol, we may have preferentially included patients who were not doing well and returned for ongoing care and subsequent endoscopies. If patients maintained remission and were doing well clinically, they might not be seen frequently and this could give the impression that long-term outcomes are worse than they actually are. This might in turn inflate the apparent proportion of patients becoming non-responsive to steroids. However, even if all 22 of the patients satisfying inclusion criteria for the study but not seen in follow-up had no treatment failure, the overall loss of response rate would still be an unacceptably high 36% (20 out of 55). Also, if high–dose steroids are more effective than low dose steroids in maintaining treatment response, one would expect differential loss of follow-up due to effective therapy to attenuate, and not accentuate our primary finding. This is because high-dose patients who were doing poorly would be preferentially included in the study. However, issues regarding differential dropout can only be definitively addressed with a prospective study with per-protocol follow-up endoscopies at regular intervals. While the small sample size is also a limitation, this is a result of our stringent inclusion criteria. We purposefully restricted the sample size to only those who had an initial response, were maintained on steroid treatment for 75–100% of the follow-up time, and had complete data on steroid dosing, and endoscopic and histologic findings. Our sample size is also comparable to other studies in adult EoE patients focusing on long-term steroid treatment outcomes.18, 28 Another limitation is that the symptom data were not collected in an objective manner with a validated symptom score, so we cannot comment on symptomatic relapse and whether symptoms correlated with histologic loss of response. Finally, patient adherence could not be fully measured due to the retrospective study design. Despite these limitations, our study adds to the existing literature and shows that rates of loss of response to steroid therapy are similar to findings in the pediatric population.18 In addition, we showed that a decrease in steroid dose results in higher risk of loss of response, and questions the current practice in many centers of routinely lowering steroid dose for maintenance therapy. If such a strategy results in high rates of possible steroid resistance, which cannot be overcome by subsequently increasing the steroid dose, perhaps maintenance at the same dose as initial induction therapy is a superior strategy. These issues will need to be carefully studied, with the symptom data collected with validated instruments, in a prospective setting in the future.

In conclusion, in this retrospective cohort study of adult EoE patients who were initial histologic responders to topical corticosteroid therapy, half had loss of histologic response by 18 months from baseline exam, with associated worsening in endoscopic findings. Maintenance of histologic response appeared to be longer with fluticasone compared to budesonide and loss of response was associated with a dose reduction of daily ≤1000 budesonide or ≤880 mcg of fluticasone. In adult EoE patients, while guidelines recommend first-line treatment with swallowed topical corticosteroids, there is little guidance regarding the duration and management of dose changes. Results of this study suggest that maintaining the initial dose of topical budesonide or fluticasone may result in persistent maintenance of histologic and endoscopic remission, and that the practice of dose reduction, which is primarily done in an attempt to minimize steroid exposure and side effects, may not be the optimal strategy for best long-term outcomes.

Study Highlights

Footnotes

Guarantor of the article: Evan S. Dellon, MD, MPH.

Specific author contributions: Project conception, study design, data collection/interpretation, data analysis, manuscript drafting, critical revision: Swathi Eluri; study design, data collection/interpretation, critical revision: Thomas M. Runge; study design, data collection/interpretation, critical revision: Jason Hansen; study design, data collection/interpretation, critical revision: Bharati Kochar; study design, data collection/interpretation, critical revision: Craig C. Reed; study design, data collection/interpretation, critical revision: Benjamin S. Robey; data collection/interpretation, critical revision: John T. Woosley; data interpretation, supervision, critical revision: Nicholas J. Shaheen; project conception, study design, data interpretation, manuscript drafting, supervision, critical revision: Evan S. Dellon.

Financial Support: This research was funded by NIH Awards T32 DK007634 (SE, TMR, BK and CR), K24 DK100548 (NJS), and R01 DK101856 (ESD).

Potential competing interests: Ecan S. Dellon is a consultant for Adare, Alvio, Banner, Receptos, Regeneron, Roche, and Shire; receives research funding from Meritage, Miraca, Nutricia, Receptos, Regeneron, and Shire; and has received an educational grant from Banner. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 128: 3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment: sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute and North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition. Gastroenterology 2007; 133: 1342–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I et al. ACG clinical guideline: Evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis(EoE). Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 679–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eluri S, Runge TM, Cotton CC et al. The extremely narrow-caliber esophagus is a treatment-resistant subphenotype of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 83: 1142–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L et al. Long-term budesonide maintenance treatment is partially effective for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9: 400–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Blanchard C et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluticasone propionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2006; 131: 1381–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L et al. Budesonide is effective in adolescent and adult patients with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2010; 139: 1526–1537, 1537.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellon ES, Sheikh A, Speck O et al. Viscous topical is more effective than nebulized steroid therapy for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2012; 143: 321–324. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butz BK, Wen T, Gleich GJ et al. Efficacy, dose reduction, and resistance to high-dose fluticasone in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2014; 147: 324–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JA, Jung KW, Arora AS et al. Swallowed fluticasone improves histologic but not symptomatic response of adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10: 742–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellon ES, Katzka DA, Collins MH et al. Budesonide oral suspension improves symptomatic, endoscopic, and histologic parameters compared with placebo in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2016; 152: 776–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SK, Vitanza JM, Collins MH. Efficacy and safety of oral budesonide suspension in pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13: 66–76 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miehlke S, Hruz P, Vieth M et al. A randomised, double-blind trial comparing budesonide formulations and dosages for short-term treatment of eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut 2016; 65: 390–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ET, Fitzgerald JF, Molleston JP et al. Comparison of oral prednisone and topical fluticasone in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: a randomized trial in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6: 165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runge T, Eluri S, Woosley JT et al. Mo1187 control of inflammation with topical steroids decreases need for subsequent esophageal dilation in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: S664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchen T, Straumann A, Safroneeva E et al. Swallowed topical corticosteroids reduce the risk for long-lasting bolus impactions in eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy 2014; 69: 1248–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellon ES, Liacouras CA. Advances in clinical management of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2014; 147: 1238–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreae DA, Hanna MG, Magid MS et al. Swallowed fluticasone propionate is an effective long-term maintenance therapy for children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111: 1187–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan J, Newbury RO, Anilkumar A et al. Long-term assessment of esophageal remodeling in patients with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis treated with topical corticosteroids. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 137: 147–156 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helou EF, Simonson J, Arora AS. 3-Yr-follow-up of topical corticosteroid treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103: 2194–2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Fritchie KJ et al. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 7: 1305–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellon ES, Kim HP, Sperry SL et al. A phenotypic analysis shows that eosinophilic esophagitis is a progressive fibrostenotic disease. Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 79: 577–585. e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runge TM, Eluri S, Cotton CC et al. Outcomes of esophageal dilation in eosinophilic esophagitis: safety, efficacy, and persistence of the fibrostenotic phenotype. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111: 206–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohil R, Newbury R, Fox L et al. Oral viscous budesonide is effective in children with eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2010; 139: 418–429. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf WA, Cotton CC, Green DJ et al. Evaluation of histologic cutpoints for treatment response in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol Res 2015; 4: 1780–1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf WA, Cotton CC, Green DJ et al. Predictors of response to steroid therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis and treatment of steroid-refractory patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13: 452–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano I, Moy N, Heckman MG et al. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut 2013; 62: 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellon E, Katzka DA, Collins MH et al. 953 Safety and efficacy of oral budesonide suspension for maintenance therapy in eosinophilic esophagitis: results from a prospective open-label study of adolescents and adults. Gastroenterology 150: S188. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell RJ, Kelleher D. Glucocorticoid resistance in inflammatory bowel disease. J Endocrinol 2003; 178: 339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]