Abstract

Background

Up to 20% of women experience anxiety and depression during the perinatal period. In the UK, management of perinatal mental health falls under the remit of GPs.

Aim

This review aimed at synthesising the available information from qualitative studies on GPs’ attitudes, recognition, and management of perinatal anxiety and depression.

Design and setting

Meta-synthesis of the available published qualitative evidence on GPs’ recognition and management of perinatal anxiety and depression.

Method

A systematic search was conducted on Embase, Medline, PsycInfo, Pubmed, Scopus, and Web of Science, and grey literature was searched using Google, Google Scholar, and British Library EThOS. Papers and reports were eligible for inclusion if they reported qualitatively on GPs’ diagnosis or treatment of perinatal anxiety or depression. The synthesis was constructed using meta-ethnography.

Results

Five themes were established from five eligible papers: labels: diagnosing depression; clinical judgement versus guidelines; care and management; use of medication; and isolation: the role of other professionals. GPs considered perinatal depression to be a psychosocial phenomenon, and were reluctant to label disorders and medicalise distress. GPs relied on their own clinical judgement more than guidelines. They reported helping patients make informed choices about treatment, and inviting them back regularly for GP visits. GPs sometimes felt isolated when dealing with perinatal mental health issues.

Conclusion

GPs often do not have timely access to appropriate psychological therapies and use several strategies to mitigate this shortfall. Training must focus on these issues and must be evaluated to consider whether this makes a difference to outcomes for patients.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, diagnosis, disease management, perinatal

INTRODUCTION

The perinatal period lasts from the onset of pregnancy until 12 months after birth. Perinatal depressive and anxiety disorders are common: about 18% of pregnant women have depression during pregnancy1 and 13–19% of new mothers have major or minor depression in the first year after delivery.1,2 Anxiety is also common, with 8% experiencing generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), 3% experiencing panic disorder, and 3% experiencing obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) in pregnancy. Following birth, up to 8% experience GAD, 9% experience panic, 2–3% experience new-onset OCD, and 3% experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3–6 The consequences of perinatal disorders are potentially more severe and far-reaching than such disorders at other times in women’s lives, having an adverse impact on the whole family if left untreated.7 Perinatal mental health is a strategic priority for health policy: although much data on costs are still missing, a recent UK report found that the annual cost to UK society of perinatal depression was £73 822 per case ($104 574),8 of which 70% resulted from the increased risk of psychological and developmental disturbances in children.7

In the UK, primary care is the first point of care for patients in the NHS, including perinatal women. This comprises GPs, midwives for pregnant women, and health visitors (community nurses specialised in maternal and child health) for new mothers and infants. England’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend that all primary care practitioners ask about possible depression and anxiety when women first have contact in pregnancy and at all subsequent perinatal contacts.9 If a perinatal mental health difficulty is identified, NICE recommends the GP as the first line of assessment and management.9

Despite GPs being in the front line of care for mental health, and the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) recognising perinatal mental health as a clinical priority,10 very little research has looked at how well GPs recognise, differentiate, and manage perinatal disorders. A recent systematic review of quantitative literature found large gaps in the literature and no studies on disorders other than depression.11 Qualitative research can provide a more detailed understanding of the complex factors that influence patient–clinician interactions and decision making. A number of studies have investigated the views of women and health visitors on help seeking and disclosure of symptoms of anxiety and depression in primary care,12–14 on women’s experience of care provided after disclosure15,16 and their preferences for taking antidepressants,17 but viewpoints of GPs have rarely been reported.18,19

Following a review of quantitative observational studies in the same area,11 the aim of this review was to synthesise qualitative studies on GPs’ attitudes, decision making, and routine clinical practice for the diagnosis and treatment of perinatal depression and anxiety in primary care.

How this fits in

Perinatal anxiety and depression is common in pregnant women and new mothers. In the UK, management of mild to moderate perinatal anxiety and depression falls under the GP’s remit but is potentially under-recognised. Qualitative studies were reviewed of GPs’ routine practice when seeing women with mild to moderate perinatal anxiety and depression. Research was sparse, but suggests that GPs consider perinatal depression to be a psychosocial phenomenon, and are frustrated at the lack of available therapy resources.

METHOD

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted conforming to the PRISMA statement, between October and December 2014 on Embase, Medline, PsycInfo, Pubmed, Scopus, and Web of Science. Broad search terms were used to ensure as many articles as possible were identified (for example, general practitioner; family physician; anxiety; depression; *natal; *partum; pregnan*; matern*;). The grey literature was searched using the same search terms on Google, Google Scholar, and British Library EThOS.

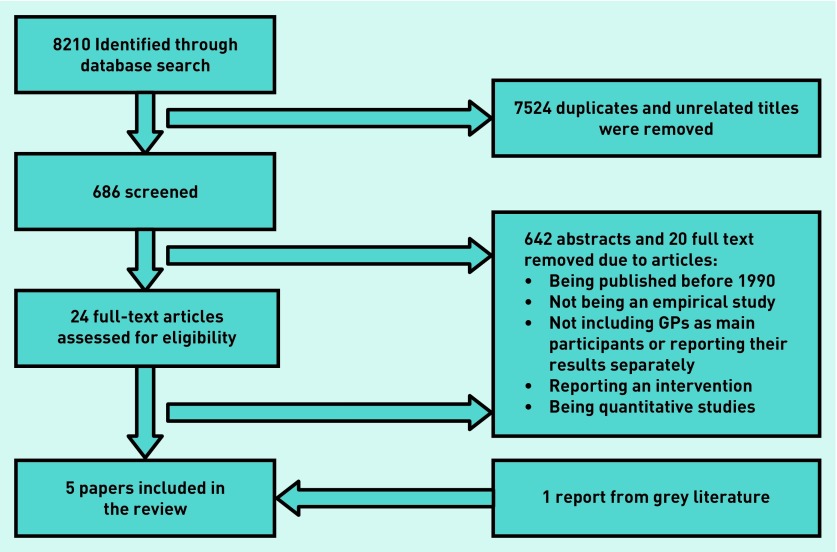

The systematic search returned 8210 papers (Figure 1). After removing duplicates and inspection of the title of each paper for relevance, 7524 papers were identified as not relevant for inclusion in this review. The abstracts of 686 papers were screened and 24 papers were scrutinised in full by two researchers. A further one eligible report was identified from the grey literature search.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

Eligibility

Papers and reports were eligible for inclusion if they reported qualitatively on GPs’ (UK, Australia, and Netherlands) or family physicians’ (FPs; US and Canada) attitudes, decision making, or routine clinical practice for the diagnosis or treatment of perinatal anxiety or depression in primary care. ‘Qualitative’ was defined very broadly to mean any results reported as text rather than numbers, and mixed-methods studies were included if they reported results analysed qualitatively. Papers were ineligible if they were published before 1990, did not report original research, were not published in English, GPs or FPs were not the main participants or reported as a separate group, or they reported interventions or quantitative results.

At the full-text stage, studies were excluded if they were not an empirical study (n = 5), if they did not include GPs as the main participant (n = 4), if they were randomised controlled trials evaluating an intervention (n = 4), and/or if they reported on quantitative methods only (n = 9) (studies were excluded for more than one reason so N >19). One Brazilian paper20 was excluded because primary care in the Brazilian healthcare system was non-comparable with general practice as described in other papers.

Quality assessment

There are no widely agreed criteria for quality of qualitative research21 or quality reporting in meta-syntheses.22 A checklist, based on that of Atkins et al21 was used to indicate the range of quality of studies and provide a means of testing the contribution of papers to the final meta-synthesis,23 but no studies were excluded on quality grounds.24

Out of 11 possible points, all studies scored 9 or 10. The checklist and results are available from the authors on request.

Analytic strategy

The synthesis was constructed using the process of meta-ethnography described by Noblit and Hare.25 The papers were read and quotes identified by two researchers. They were then re-read and key themes were identified by one of those researchers. Tables were constructed for each paper showing first- and second-order constructs for each theme. The definitions of these constructs were taken from Malpass et al,23 where first-order constructs are considered to be participants’ ‘views, accounts and interpretations’, that is, direct quotes from participants. Second-order constructs are considered to be ‘authors’ views and interpretations … of patients’ views’, that is, analytic commentary on the first-order constructs.

Using these tables, studies were then translated into one another using the processes of reciprocal and refutational translation.25 Quotes from participants were used to support the credibility of the new themes and to demonstrate their traceability back to the originals.26 To bring fresh insights and new understandings, a line of argument synthesis was carried out so that the translated themes were organised into a logical and coherent order.27 All authors read and agreed the thematic structure of results. Data on the structure of themes are available from the authors on request.

RESULTS

Studies

Five papers were found that met eligibility criteria, reporting on views from 323 GPs (Table 1). Three papers, reporting on depression only, used interviews to elicit GPs’ views.28–30 One paper reported content analysis of open questions in a survey31 and the fifth,32 a non-peer-reviewed report, covered perinatal mental health more generally. These papers were included because of the early stage of research in the area but their findings were used to support themes found in the other studies rather than initiating themes. Three papers focused on the postnatal period,28,29,31 one on pregnancy,30 and one on the ‘perinatal period’.32

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Authors | Country | Method | Sample | Sampling approach/response rate | Primary objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chew-Graham et al (2008) 28 | UK | In-depth interviews, thematic analysis | Purposive sample of 19 GPs recruited from participants in multicentre RCT (RESPOND — Randomised Evaluation of antidepressants and Support for women with POstNatal Depression) | Sampling was purposive and sought to achieve maximum variation in relation to GPs’ age, sex, length of time in general practice, practice size and level of deprivation | To explore the views of GPs and health visitors on the diagnosis and management of postnatal depression |

| Chew-Graham et al (2009) 29 | UK | In-depth interviews, thematic analysis | Same sample as Chew-Graham (2008) above | As above | To explore GPs’, health visitors’, and females’ views on the disclosure of symptoms that may indicate depression in primary care |

| Jayawickrama et al (2010) 31 | Australia | Anonymous postal survey, content analysis | 335 GPs: 70% female 37% aged 45–54 years 84% obtained medical degree in Australia 90% had children 49% of them (or their partners) had >12 months experience of breastfeeding | 125/640 (19.5%) GPs responded to survey and provided open-ended comments on prescribing decisions, 54 GPs (8.4%) mentioned depression | Explore GPs’ decision making when they are considering recommending or prescribing medication for a breastfeeding woman |

| McCauley and Casson (2013) 30 | UK (Northern Ireland) | Semi-structured interviews, Colaizzi’s process of analysis | Eight GPs: two male, six female | Ten practice managers were invited to identify GPs who were eligible for involvement, eight GPs were identified | Develop an in-depth understanding of GPs’ experience of using guidelines in the treatment of perinatal depression and if this enabled them to empower women to become involved in treatment decisions |

| Khan (2015) 32 | Mainly UK | Postal survey plus semi-structured interview with three survey responders, interpretive phenomenology | 43 GPs: 40 from England, one from Wales, one from Scotland, one from India Over half had <11 years’ experience in general practice, just over a third had practised for 1–3 years. Just over a quarter had >20 years’ experience. 14% felt they held a partially specialist role in perinatal mental health care | The GP survey was distributed to an unknown but large number of GPs through virtual portals. Only 43 GPs responded | To better understand the contribution of GPs to the area of perinatal mental health |

Findings

Five themes were established from five eligible papers:

labels: diagnosing depression;

clinical judgement versus guidelines;

care and management;

use of medication; and

isolation: the role of other professionals.

Table 2 shows which themes were drawn from which studies.

Table 2.

Themes drawn from the five studies

| Study | Theme | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labels: diagnosing depression | Clinical judgement versus guidelines | Care and management | Use of medication | Isolation: role of other professionals | |

| Chew-Graham et al (2008)28 | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Chew-Graham et al (2009)29 | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| Jayawickrama et al (2010)31 | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| McCauley and Casson (2013)30 | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | – |

| Khan (2015)32 | – | – | Yes | – | Yes |

Labels: diagnosing depression

GPs described conceptualising depression in psychosocial rather than biomedical terms and could be reluctant to identify the condition with a diagnostic label:

‘I call it emotional turmoil rather than depression, psychological disturbance, at various stages after the birth, and I don’t think of them as adjustment disorders, and often they are what I would think of as “existential crises”.’ 28,29

This could reflect an overall approach to management and a preference for non-pharmacological interventions:

‘I don’t want to medicalise it too much really I think it needs to be an informal sort of network because I do think most of the time people do recover from it if they are just given some support rather than medication.’ 28,29

It could, however, also result from a necessarily pragmatic perspective in the face of limited service availability:

‘If I call it depression, I need to do something. There’s no one to refer to, so I would rather call it something else and manage her myself.’ 28,29

GPs also referred to women’s reactions in the face of diagnosis and how these could influence their definition of the condition. Some women were wary of being labelled even when they were presenting in distress:

‘I mean, if they deny that they have got a problem but are still in tears, it becomes very difficult, because you can’t treat somebody if they don’t accept that there’s something to treat.’ 29

Others could be more willing to acknowledge there was something wrong:

‘And equally others will just come in and say “My husband said I’ve got to get this sorted out, and I need a tablet to calm me down” or whatever.’ 29

Clinical judgement versus guidelines

GPs often reported relying on their own judgement in detection of depression and anxiety:

‘I think any kind of flatness, it’s a difficult thing to explain, isn’t it? You can just tell by having a conversation, just chatting to them.’ 28,29

Clinical intuition was considered to be a reliable tool for identifying women with symptoms in preference to formal detection instruments such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale,33 but there was some reluctance to consciously ask about symptoms:

‘So I’m not saying I actively look for it, but I am hoping my antennae would tell me if there was a problem.’28,29

This preference for the use of clinical judgement also extended to decisions about treatment where clinical judgement was again seen as a more appropriate decision-making tool than formal guidelines:

‘I’m not a robot and doctors aren’t programmed to be robots … and you get to know your patients and you know who needs an antidepressant and who doesn’t.’30

Sometimes guidelines were not followed because it was considered that there was a lack of evidence to support them and the advice of trusted colleagues was perceived to be more reliable:

‘Depression. Most information is “personal decision” i.e. no good evidence. Reasons for decision — local psychiatrist opinion, [hospital] pharmacist’s opinion. Difficult finding up to date info.’ 31

Guidelines were also not regarded as the best way of identifying the optimum management plan for individual patients:

‘NICE guidelines are useful but I think you need to put your own experience into play as well, a lot of the time NICE guidelines are very strict and if you go strictly by the guidelines then quite often you don’t necessarily give the patient what they need or what help they need.’ 30

This reliance on individual judgement could lead to concerns about professional accountability:

‘There is no clear professional guidance either and you always feel a little bit isolated when that’s the case and a little bit at risk because you’re kind of working off your own experience.’ 30

Care and management

Some GPs described ensuring they made time for women with depression or anxiety:

‘Once you kind of know they’re in distress you don’t just give them one session, you ask them to come back always, you get them to come back two weeks later to see how they’re doing.’ 29

Although this approach was considered generally beneficial, it also raised its own issues:

‘It’s quite time consuming from the GP’s point of view that you end up seeing them much more often than you would if they weren’t on medication.’ 30

GPs acknowledged they relied on using medication, together with seeing the patient regularly, more often than was ideal because of a lack of other treatment options:

‘I mean, it’s best if it’s a multiple approach rather than just drugs. Unfortunately that’s all we can offer.’ 29

There was perceived to be a shortfall in the provision of talking therapies available for women:

‘Services are too stretched and referrals are refused.’ 32

GPs reported that they generally involved women in decisions about their care:

‘Postnatal depression. Antidepressant prescribed after long discussion with patient re: prob. areas and current literature/discussion re: safety and proven side effects. I was happy with the decision and I felt the patient was happy.’31

This was perceived as empowering for women and likely to improve compliance with treatment and improve outcomes:

‘It means giving patients the freedom and the confidence and the information they need to make their own decisions … I think if we can’t give patients empowerment then they can’t really be well or stay well.’30

It was acknowledged that this approach should be tailored according to the needs of individual women:

‘There’s the doctor centred consult where it’s “What do you think doctor?” and I say what I think and I give you what I think and you go away happy or there is a different type of patient who like the patient-centred consult which involves the patient’s agenda. I think the key in general practice is to pick up on the cue of which patient wants which particular style.’ 30

GPs also identified an occasional need for further intervention in the interests of safety:

‘Patient empowerment is good, but you have to, if you felt it was harming to themselves or to their baby you would have to maybe take stronger action.’30

GPs’ approach to the care of women with depression could be influenced by personal experience:

‘Tragically it is only because of my own personal experience of severe postnatal depression 8 years ago and my struggle to find help and treatment … has the perinatal mental health of my patients become a priority for me … I am very sensitive to this in my patients and have a high pick up rate and aim to provide excellent multidisciplinary care for patient and her baby/family.’32

It could also be altered by increased awareness of the issue:

‘It is quite recent that after a workshop I became more aware of this and since then I have diagnosed about 5–7 ladies and looked after them including referral to perinatal mental health service in our area.’32

Use of medication

GPs recognised that their use of medication was influenced by a lack of other services:

‘If I had easier access to counselling … my use of antidepressants would be much less.’30

Some described anxieties regarding prescribing medication to breastfeeding or pregnant mothers:

‘Concerns about SSRI during breastfeeding by both me and patient. Decision making process is always fraught and made difficult by conflicting information.’31

This anxiety occurred more often in relation to psychotropic drugs than other kinds of medication used in the perinatal period. There was, however, an acknowledgement that antidepressants were a necessary intervention for some women:

‘If I felt that somebody’s mental state was such that they were at risk, that their quality of life was … so bad that they weren’t going to have a good pregnancy, I would have no problem with prescribing.’30

GPs’ concerns about prescribing for breastfeeding women sometimes resulted in them being given unnecessarily cautious advice regarding breastfeeding, but others took an evidence-based approach and stressed the importance of continued breastfeeding:

‘Postnatal depression. Prescribed Zoloft [sertraline] advised to continue breastfeeding. Benefit outweigh risks. I felt okay with decision.’31

When GPs did wish to prescribe antidepressants, this could be met with reluctance by women:

‘Patient’s reluctance despite reassurance. No problem for me, but patient very reluctant to take anything.’31

Women’s concerns sometimes resulted in them making decisions about their medication without consultation with their GPs:

Isolation: the role of other professionals

GPs reported concerns that changes to the organisation of perinatal healthcare services, in particular their decreased contact with health visitors, had led to a worsening of service quality:

‘ [I now have] much less opportunity [to identify women]. [I] used to do joint clinics with [the] health visitor [but these have] now stopped so communication with other healthcare professionals [is] poor. I feel I am seeing fewer patients with post-natal depression which cannot be correct.’ 32

Concerns included lack of continuity of service:

‘Where we used to have a health visitor who was assigned to us, who we could discuss cases with, we are now assigned to a local team, so it could be anybody and it could change from day to day who the patient’s health visitor is and which team they are working for.’28

There was also uncertainty about both their own role and that of health visitors under the new system:

‘I feel my role has been marginalised since joint working with health visitors has effectively stopped.’32

‘Because I think [health visitors] seem very constrained on what they are prepared to do really. I think that they seem just to play a very non-interventionalist role and see themselves as being preventative, which I think is quite tragic.’28

Other professionals were sometimes consulted for advice regarding the management of women:

‘The pharmacist at [hospital] excellent — gives various sources of information and good opinion re: overall management. If not in, she always rings you back — very reliable.’ 31

This happened more often when the GP knew and trusted the individual professional. Otherwise, advice from others was not always perceived as useful:

‘Pharmacist [s] tend to be too conservative and advise against taking anything. Also, they sometimes provide advice against what I say and alarm patients.’31

DISCUSSION

Summary

This meta-synthesis shows that GPs consider perinatal depression within the context of women’s lives and are frustrated at the lack of talking-therapy resources they have available. It is clear that GPs try to plug the gap in mental health services by inviting women back regularly, thus developing a potentially therapeutic trusting relationship. Much more research is needed in this area, and particularly in how GPs manage perinatal anxiety, to inform training and resource interventions.

Where interventions are implemented, they must be evaluated to consider whether they make a difference to outcomes for women.

Strengths and limitations

The present search strategy was comprehensive so it is likely all available literature was captured, and the methodology for synthesising the papers was robust. Only one researcher screened titles and abstracts, however, which may have made study selection unreliable. The small number of studies and small samples mean that these findings represent only a narrow range of views, are not generalisable, and are likely to be subject to selection bias. Additionally, because of the small range of literature available, a lower-quality study was included, which used open-ended survey responses and a non-peer-reviewed report. The survey study was focused on prescribing for breastfeeding women rather than perinatal mental health, thus results from this study could only support rather than initiate themes. Additionally, no evidence was found for how perinatal anxiety is recognised or managed in primary care. Studies all originated from English-speaking countries (UK and Australia) and, given that four of the five were UK based, these results are very UK focused. Much more research is needed in this area to confirm these findings and set them in context, and explore how GPs manage perinatal mental health in other countries.

Comparison with existing literature

This meta-synthesis has highlighted that GPs consider perinatal depression a psychosocial phenomenon rather than a biomedical one, leading to a reluctance to label disorders and medicalise distress. This finding is congruent with other commentaries on recognition and management of depression in UK general practice.34 Practitioners vary considerably in the threshold at which they will label patients as cases needing treatments because depressive symptoms are widely distributed through the population and change quickly.35 GPs see a range of social problems leading to distress and sadness, so doubt the effectiveness of antidepressants35 and doubt that patients’ problems are solvable with medical treatment.36 This can lead them to approach disclosures of mental health symptoms with reassurance, or a ‘watch and wait’ approach.

Women may perceive this response as their symptoms being minimised and dismissed,37–39 after which they may become reluctant to pursue treatment.40 ‘Watch and wait’ is also potentially an inappropriate strategy in the perinatal period when suicide is a real risk41 and disorders may have profound impacts on the child’s emotional and behavioural development.7 Some evidence suggests that, when trusting relationships with healthcare professionals have time to develop, the risk of dismissing new or important symptoms is diminished.42 It could be argued that, rather than offering lesser treatments for perinatal women with anxiety or depression, GPs should be more proactive about initiating treatment during this vulnerable period, compared with at other times in a woman’s life.

The second theme suggests that GPs rely on their own clinical judgement more than established or evidence-based guidelines. Doctors’ confidence in their decisions is not, however, always related to their accuracy.43 When guidelines are not used in practice, unconscious biases can occur throughout doctors’ interactions with patients, such as selectively gathering and interpreting evidence that confirms a diagnosis and ignoring evidence that might disconfirm it.44 The adoption of evidence-based approaches and decision or screening tools may improve the quality of doctors’ reasoning, but more research is needed to confirm this. Insight via education appears to be the major means in which to avoid distorted decision-making processes.45

GPs reported on helping their patients to make informed choices about treatment, and on attempting to plug the gap in availability of ‘talking’ therapies by inviting women to come back regularly for GP visits. They prescribed antidepressants despite recognition that a psychological therapy may be more appropriate. This suggests a tension between what GPs consider to be best practice and what they can practicably offer. Studies suggest GPs are aware of patients’ dislike and reluctance to take antidepressants,35,46 and would prefer to offer patients treatments aligned with their preferences.

The final theme suggests that GPs feel isolated when dealing with perinatal mental health issues. Over recent years midwives’ and especially health visitors’ methods of working have moved from case loading and affiliation to a particular GP surgery, to corporate team working, where it is harder for professional relationships to develop. This may have reduced collaboration between different specialties, and may risk women losing out on joined-up care. For example, Chew-Graham et al 28 reported health visitors as having negative attitudes to GPs, and as saying that GPs do not have a ‘sympathetic attitude’ and would ‘just write a prescription’. Given that health visiting services are now commissioned by the local authority rather than the NHS, the coordination and continuity of care are becoming harder rather than easier within the primary care and community environment.

Implications for research and practice

Research with GPs on how they manage perinatal depression is currently sparse, and none was found exploring perinatal anxiety or PTSD. Future research is needed at all levels of the primary care pathway, from recognition of psychological distress, to outcomes of treatment both within primary care and following referral to specialist services.47 Training and resource interventions should be evaluated to see if they improve outcomes for women, their infants, and their families.

Continuity of care and trusting relationships are found to be important in the literature on women’s perception of help seeking. It is unlikely, however, that GPs will have more routine antenatal contact with pregnant women to develop a sense of continuity,48 or closer working relationships with midwives and health visitors in the near future. One potential strategy is for practices to have a GP lead for maternity and maternal mental health who regularly meets with local midwives and health visitors, coordinates strategy within the practice, and is visibly available for patients to consult with about perinatal mental health issues. A key issue for GPs is also to have specialist community perinatal mental health services available to refer patients to in a timely way. Very recently, there has been considerable investment in specialist perinatal mental health by the current UK government, for example, development of Mother and Baby Units and specialist community teams, but little so far to address the common mental health problems that are usually managed in primary care.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the help of Maithreyee Vipulananthan and Fatin Elias in conducting the literature searches.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

None required for this paper as it is a literature review.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, et al. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5, Part 1):1071–1083. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression — a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996;8(1):37–54. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zambaldi CF, Cantilino A, Montenegro AC, et al. Postpartum obsessive-compulsive disorder: prevalence and clinical characteristics. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50(6):503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross LE, McLean LM. Anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(8):1285–1298. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grekin R, O’Hara MW. Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(5):389–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farr SL, Dietz PM, O’Hara MW, et al. Postpartum anxiety and comorbid depression in a population-based sample of women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014;23(2):120–128. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, et al. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet. 2014;384(9956):1800–1819. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauer A, Parsonage M, Knapp M, et al. The costs of perinatal mental health problems. 2014 https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/costs-of-perinatal-mh-problems (accessed 15 May 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance. CG192. London: NICE; 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192 (accessed 15 May 2017) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayers S, Shakespeare J. Should perinatal mental health be everyone’s business? Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2015;16(4):323–325. doi: 10.1017/S1463423615000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford E, Shakespeare J, Elias F, Ayers S. Recognition and management of perinatal depression and anxiety by general practitioners: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2017;34(1):1119. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmw101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dennis CL, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: a qualitative systematic review. Birth. 2006;33(4):323–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slade P, Morrell CJ, Rigby A, et al. Postnatal women’s experiences of management of depressive symptoms: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2010 doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X532611. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp10X532611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russell K, Ashley A, Chan G, et al. Maternal mental health — women’s voices. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shakespeare J, Blake F, Garcia J. How do women with postnatal depression experience listening visits in primary care? A qualitative interview study. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2006;24(2):149–162. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sword W, Busser D, Ganann R, et al. Women’s care-seeking experiences after referral for postpartum depression. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(9):1161–1173. doi: 10.1177/1049732308321736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner KM, Sharp D, Folkes L, Chew-Graham C. Women’s views and experiences of antidepressants as a treatment for postnatal depression: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2008;25(6):450–455. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oates MR, Cox JL, Neema S, et al. Postnatal depression across countries and cultures: a qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2004;46:s10–16. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.46.s10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boots Family Trust Alliance. Perinatal mental health: experiences of women and health professionals. 2013 http://www.bftalliance.co.uk/the-report/ (accessed 15 May 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos Junior HP, Gualda DMR, Silveira MdFA, Hall WA. Postpartum depression: the (in) experience of Brazilian primary healthcare professionals. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(6):1248–1258. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atkins S, Lewin S, Smith H, et al. Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: lessons learnt. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dheensa S, Metcalfe A, Williams RA. Men’s experiences of antenatal screening: a metasynthesis of the qualitative research. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(1):121–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malpass A, Shaw A, Sharp D, et al. ‘Medication career’ or ‘moral career’? The two sides of managing antidepressants: a meta-ethnography of patients’ experience of antidepressants. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(1):154–168. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandelowski M, Docherty S, Emden C. Focus on qualitative methods. Qualitative metasynthesis: issues and techniques. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20:365–372. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199708)20:4<365::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications Inc; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen LA, Allen MN. Meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Qual Health Res. 1996;6(4):553–560. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh D, Downe S. Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;50(2):204–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chew-Graham C, Chamberlain E, Turner K, et al. GPs’ and health visitors’ views on the diagnosis and management of postnatal depression: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2008 doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X277212. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp08X277212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chew-Graham CA, Sharp D, Chamberlain E, et al. Disclosure of symptoms of postnatal depression, the perspectives of health professionals and women: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-10-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCauley C-O, Casson K. A qualitative study into how guidelines facilitate general practitioners to empower women to make decisions regarding antidepressant use in pregnancy. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2013;15(1):3–28. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jayawickrama HS, Amir LH, Pirotta MV. GPs’ decision-making when prescribing medicines for breastfeeding women: content analysis of a survey. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:82. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan L. Falling through the gaps: perinatal mental health and general practice. London: Centre for Mental Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas-MacLean R, Stoppard JM. Physicians’ constructions of depression: inside/outside the boundaries of medicalization. Health (London) 2004;8(3):275–293. doi: 10.1177/1363459304043461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kendrick T. Why can’t GPs follow guidelines on depression? We must question the basis of the guidelines themselves. BMJ. 2000;320(7229):200–201. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7229.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maxwell M. Women’s and doctors’ accounts of their experiences of depression in primary care: the influence of social and moral reasoning on patients’ and doctors’ decisions. Chronic Illn. 2005;1(1):61–71. doi: 10.1177/17423953050010010401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McIntosh J. Postpartum depression: women’s help-seeking behaviour and perceptions of cause. J Adv Nurs. 1993;18(2):178–184. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18020178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mauthner NS. Postnatal depression: how can midwives help? Midwifery. 1997;13(4):163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(97)80002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amankwaa LC. Postpartum depression among African-American women. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2003;24(3):297–316. doi: 10.1080/01612840305283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edge D, Baker D, Rogers A. Perinatal depression among black Caribbean women. Health Soc Care Community. 2004;12(5):430–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knight M, Kenyon S, Brocklehurst P, et al. Saving lives, improving mothers’ care — lessons learned to inform future maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2009–12. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Megnin-Viggars O, Symington I, Howard LM, Pilling S. Experience of care for mental health problems in the antenatal or postnatal period for women in the UK: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18(6):745–759. doi: 10.1007/s00737-015-0548-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berner ES, Graber M. Overconfidence as a cause of diagnostic error in medicine. Am J Med. 2008;121(5 Suppl):S2–S3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moskowitz AJ, Kuipers BJ, Kassirer JP. Dealing with uncertainty, risks, and tradeoffs in clinical decisions. A cognitive science approach. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108(3):435–449. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-3-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hall KH. Reviewing intuitive decision-making and uncertainty: the implications for medical education. Med Educ. 2002;36(3):216–224. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hyde J, Calnan M, Prior L, et al. A qualitative study exploring how GPs decide to prescribe antidepressants. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(519):755–762. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldberg DP, Huxley P. Mental illness in the community: the pathway to psychiatric care. London: Tavistock Publications Ltd; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Maternity Review. Better births Improving outcomes in maternity services in England A five year forward view for maternity care. 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/national-maternity-review-report.pdf (accessed 15 May 2017)