Abstract

Though the presence, composition, and quality of social relationships—particularly as found in family networks—has an important influence on adolescent well-being, little is known about the social ecology of youth in foster care. This study examined the social networks of foster youth participating in a large RCT of an intervention for siblings in foster care. Youth reported on the people they lived with and the relatives they were in contact with, which provided indicators of network size, composition, and relationship quality. Cluster analysis was used to identify five family network profiles for youth living in foster homes. Two identified subgroups reflected robust family networks where youth were living with relative caregiver(s) and related youth, and also reported multiple family ties outside the household, including with biological parents. The remaining three profiles reflected youth reports of fewer family connections within or beyond the foster household, with distinctions by whether they lived with siblings and/or reported having positive relationships with their mothers and/or fathers. The identified network profiles were validated using youth- and caregiver-reported measures of mental health functioning, with increased caregiver report of post-traumatic stress symptoms indicated for the three subgroups that were not characterized by a robust family network.

Keywords: foster youth, social networks, social ecology, kinship care, child welfare

Introduction

Research has documented that the presence, consistency, and quality of caregiving relationships influence adolescent psychosocial development (Steinberg, 2001) and affect youth safety and wellbeing (Fox, Berrick, & Frasch, 2008). Adolescents in out-of-home foster care have by definition experienced some degree of disruption in normative caregiver relationships and studies have documented the importance of a network of caregiving adults in contributing to the well-being of youth in foster care (Cushing, Samuels, & Kerman, 2014; Perry, 2006). Furthermore, evidence suggests that stable placement in family-based settings is associated with better adaptation and functioning (Aarons et al., 2010; Barber & Delfabbro, 2003; Newton, Litrownik, & Landsverk, 2000; Rubin, O'Reilly, Luan, & Localio, 2007). Although research highlights the importance of the social ecology of foster youth, little is known about their family networks after they are placed in foster care. Few child welfare studies have described the social ecology of adults, relatives, siblings, and others involved in the lives of foster youth, evaluated the composition of adults and other individuals forming the social networks of youth in foster care, or focused on foster youth perceptions of these individuals.

Social Ecology of Youth in Foster Care

Social ecology refers to the “nested arrangement of family, school, neighborhood, and community contexts in which children grow up” (Earls & Carlson, 2001, p. 143), and proximal contexts, specifically familial relationships, are a focal point in understanding children's health and well-being. However, foster youth's social contexts are often complex and may include biological and foster family members, as well as children and adults who are not related by residence or blood. Given the importance of these familial relationships, kinship and non-kinship foster families have been compared in a number of ways (e.g., Farmer, 2009), although evidence suggests heterogeneity within these groups, with much attention to variation in kinship care (Berrick & Hernandez, 2016; Storer et al., 2014; Zinn, 2010). Further, non-relative foster family members are often incorporated in youth's definitions of family (Ellingsen, Stephens, & Storksen, 2012; Gardner, 1996), and family structure and household composition differ within and between placement types, as does the presence and quality of contact between biological family ties and people in the foster home (Hedin, 2014; Kiraly & Humphreys, 2013).

Although these proximal networks are critical contexts within which foster youth experience adolescence, little attention has been paid to the ways in which foster youth perceive their key relationships, and few studies have examined how foster youth negotiate the presence and quality of these complex and potentially multiple family relationships and identities (Biehal, 2012; Storer et al., 2014). In family foster care settings, youth relationships center on caregiving figures (biological and foster), other adults (notably relatives), and other proximal youth (including siblings and other youth within foster settings). Placement(s) in foster homes is the primary intervention most youth experience as wards of the state; therefore, it is imperative to understand this immediate context and the relationships within it to determine which factors create a nurturing environment (Biglan et al., 2012).

The current study takes a person-oriented approach to describe foster youth perceptions of the social ecology centered within their specific foster home placements. Recent person-oriented studies have identified subgroups of older foster youth with distinct profiles in terms of individual-level predictors (e.g., behavior, placement type) (Keller, Cusick, & Courtney, 2007) and longer-term outcomes (Courtney, Hook, & Lee, 2012; Yates & Grey, 2012). Some studies have taken a more ecological approach to understanding subgroups of maltreated children and youth by considering their short-term placement contexts versus long-term preferences (Merritt, 2008), and by including factors beyond the individual, such as family structure and caregiver absence prior to coming into foster care (Yampolskaya et al., 2014). A recent profile analysis with foster youth at age 22 measured dimensions of relationships with birth parents and other parental figures, and found that those who reported supportive ties to both of these had the most promising outcomes (e.g., high competence and low vulnerability) (Cushing, Samuels, & Kerman, 2014). These person-oriented child welfare studies and other profile analyses of vulnerable youth populations (Etzion & Romi, 2015; Mallet et al., 2004; Milburn et al., 2009) have identified distinct subgroups that may be used by policymakers and program developers to refine services to address the socio-emotional and relational needs of different types of youth.

Despite the potential policy and programmatic benefit of understanding the networked relationships forming the social ecology of youth in care, few studies have sought to describe the constellations of key individuals surrounding youth in foster homes. In general, little is known about foster youth networks, in terms of structural characteristics of size and composition, or the combinations of relational characteristics occurring in different kinds of networks for youth with child welfare involvement (Blakeslee, 2012). However, two recent studies highlight family network factors for youth in foster care. Perry (2006) found that psychological distress due to experiences of foster placement-related disruption of family and friend networks was alleviated when weak or absent network ties were replaced by strong and supportive ties to other members of the biological family, new foster family members, or peers. More recently, Negriff and colleagues (2014) measured networks of early adolescents with open maltreatment cases and found that compared to a non-maltreated sample, the number of supportive relationships (notably biological parents) in these networks decreased over time. There was not a difference in the presence of a supportive biological parents by relative care versus non-relative care, though youth in non-relative care were less likely to identify their caregiver as supportive, compared to youth in relative care or those living with a biological parent. Overall, the authors concluded that out-of-home care is detrimental to maintaining youth ties to biological parents, though placement stability is associated with retaining family members in networks, including a supportive biological parent (Negriff, James, & Trickett, 2014). Taken together, the extant research highlights the importance of evaluating the composition, consistency over time, and quality of the connections between youth and those individuals forming their social network.

In applying a network perspective to the description of the social ecology of adolescents in foster care, of concern are the measurement of dimensions of (a) network structure and (b) network composition according to established theory and methods (Blakeslee, 2012). A fundamental measure of network structure is size, because the number of people in a network determines the potential support available to network members (Barerra, Sandler, & Ramsay, 1981; Walker, et al., 1993). For adolescents in foster care, network size can be an indicator of “support capacity” (Blakeslee, 2015), in terms of the presence of people who may potentially provide a range of emotional, informational, or tangible resources to address youth needs. Measures of network composition help determine what these people may bring to the network. Sociological research suggests that the provision of emotional and concrete support—whether this is provided day-to-day or in response to a crisis—often occurs through long-term, family-based (or family-like) relationships (e.g., Wellman & Gulia, 1999; Wellman & Wortley, 1990). This also relates to relationship strength, in that stronger relationships are marked by relationship stability and the provision of a range of support (e.g., Degenne & Lebeaux, 2005; Walker, Wasserman, & Wellman, 1993). In summary, an ideal social network for an adolescent in foster care might include a core group of strong ties that are connected to the youth and to each other, such that they can easily communicate about a youth's needs and coordinate multi-dimensional support (Morgan, Neal, & Carder, 1997; Wellman, Wong, Tindall, & Nazer, 1997).

More generally, social network dimensions can be used to frame and explore questions of interest about the social ecology of youth in foster care in ways that may advance research and practice towards a more comprehensive understanding of foster youth social context. Such approaches can move beyond traditional administrative proxies for aspects of social ecology, such as placement type or permanency plan designation. For example, placement with relatives is considered desirable in policy and practice, likely because kinship care is assumed to provide youth with access to proximal social contexts in which there exist patterns of relationship characteristics (e.g., supportive, long-term, permanent) that reflect extant family and cultural relational norms and structural stability. A more socioecological approach frames kinship care as a type of placement marked by certain network characteristics, as opposed to a caregiver or placement designation. Table 1 outlines this approach, in terms of network dimensions of interest for understanding the social ecology of youth in care. Stated differently, the aim is to begin to explore how familial social context might be described for youth in foster placements by exploring network dimensions associated with family network functioning, such as adequate network size, interconnection between members, and a core of high-quality relationships.

Table 1. Question-based rubric for understanding the social context of youth in foster care.

| Network Dimensions | Socioecological Questions |

|---|---|

| Composition |

|

| Structure |

|

| Relationship Characteristics |

|

Study Aims

The primary aim of the current investigation was to take a preliminary network perspective in analyzing an existing dataset that included pre-adolescent and adolescent foster youth reports of the different people they lived with, visited with, and/or were in contact with. This exploratory study took a person-centered approach to describing the reported socio-ecological context of these youth in terms of networks of various family or household-based social roles, including biological or otherwise-related family members and any non-relative adults or youth in the foster family household. In keeping with network-oriented approaches, these networks were conceptualized as having measurable characteristics related to the size and composition of the networks, the strength of particular relationships, and the combination of relationships that constitute the identified network as a whole.

Clustering methodology was employed given that its flexibility suited the exploratory nature of the research. Cluster analysis was preferred to other methods (e.g., latent class analysis) because it can accommodate any combination of continuous or categorical variables, and it assigns cases to groups for follow-up analysis (rather than resulting in an estimated probability that a case would fall into a group). The purpose was to develop and validate profiles of family networks or constellations reported by youth living in foster family settings using youth- and caregiver-reported measures of youth mental health and functioning. Describing these various important relationships in terms of interpretable socio-ecological profiles, or “types” of family networks, can help child welfare researchers, practitioners, and policy makers better understand the social resources available (or unavailable) to youth in foster care contexts.

Importantly, this study also sought to illuminate the youth's perspective on their family network. A recent review (Prichett et al., 2013) highlighted that foster youth research often relies upon administrative data or state-sanctioned reporting agents (e.g., caregivers, caseworkers), rather than youth themselves. Reliance upon administrative data and adult perspectives is less appropriate when the research purpose is to develop valid understandings of the quality of the connections youth have with others within often fluid social networks. As children and youth in foster care do not always have stable relationships with adults, it is particularly important for studies to solicit and attend closely to youth perceptions of their social environments.

Methods

Data for this investigation were drawn from Supporting Siblings in Foster Care (SIBS-FC), the first large-scale randomized clinical trial to evaluate a sibling relationship development intervention for preadolescent and adolescent foster youth. The behavioral intervention program tested in the SIBS-FC study was designed specifically for pre-adolescent youth in foster care. The study utilized a universal recruitment strategy that drew from the population of sibling pairs from a three-county metropolitan region. To be eligible for participation, youth had to be in the legal custody of the local child welfare agency at the time of study enrollment, reside in the three-county region, meet age eligibility requirements and speak English. The study limited inclusion to older siblings in care between 11 and 15 years of age, with the younger sibling within four years of age (Kothari et al., 2014, Kothari et al., 2017 and McBeath et al., 2014).

Siblings in the intervention group were taught and practiced communication, cooperation, and problem solving skills, as well as ways they could improve their relationship. Sibling dyads living together and sibling dyads living apart participated in the study. Findings suggest that this program was delivered with a high degree of fidelity, was feasible and well-liked by foster youth (Kothari et al., 2014), and improved sibling relationship quality among those in the intervention group (Kothari et al., 2017). The SIBS-FC study utilized a multiple method, multiple indicator data collection and measurement strategy (Chamberlain & Bank, 1989). Data were collected by trained assessors between 2010-2015 on the major project domains (i.e., mental health, education, quality of life, and sibling relationship quality) using multiple methods across the 18-months families were enrolled in the study. Assessors completed in-person interviews with youth participants (i.e., older and younger siblings) which included video-recorded observation. Data were also collected from foster parents/caregivers via surveys and phone calls, and from teachers and caseworkers via a web-based platform (i.e., Qualtrics). Outside observers also completed rating forms. At the end of study participation, administrative data was collected from the state's Department of Human Services (DHS) and Department of Education (DOE).

Participants

SIBS-FC Study Participants

In the larger SIBS-FC study, data were gathered from 164 sibling pairs (328 total youth in foster care), for a total of 164 older siblings (mean age=13.1, SD=1.4) and 164 younger siblings (mean age=10.7, SD=1.7). The average age difference between siblings was 2.4 years (SD=1.1). The majority of youth were full siblings (62%, n=202); almost three-quarters lived in the same foster placement (73%, n=238); and 60% (n=201) identified as non-White. Approximately equal numbers were male and female. At baseline, slightly over half of youth lived in non-relative foster settings (56%, n=183) and had been living with their current caregiver for over 2 years.

This sample has similarities to both the Oregon child welfare population and the national child welfare population. Data reported from the 2012 fiscal year (approximately the midpoint of this longitudinal study) indicated that 39% of Oregon foster youth were in the 7–15 year age range and 42% were non-Caucasian (USDHHS, 2012). In addition, the 2012 Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) report indicated that 39% of youth in foster care nationally were in this 7–15 year age range and 58% were persons of color.

As described above, longitudinal data in the larger SIBS-FC randomized clinical trial (RCT) were collected from multiple informants and from administrative records over an 18-month period. The primary purpose of the RCT was to test the efficacy of a dyadic sibling-relationship enhancing intervention (see Kothari et al., 2014 and Kothari et al., 2017 and McBeath et al., 2014 for additional details). Youth in this larger study were universally recruited from the Department of Human Services; therefore, this existing longitudinal data set provides a rich source of information for understanding children and youth in foster care.

Sample for this Study

The current study examined the social ecology of foster youth using baseline data from the SIBS-FC study. This study specifically explores the proximal networks of youth in family foster care settings, which would include relative caregivers or unrelated foster parents, as well as biological parents and other family members. Therefore, youth living in residential care settings, pre-adoptive homes, and those in trial reunification with their parent(s) (13% of baseline sample) were not included in the analysis so as to consistently include foster caregivers in the networks. Because the sibling pairs are expected to be highly correlated on many of the indicators, this analysis excluded younger siblings, resulting in a sample of 143 older siblings. The mean age for this sample was 13 years (ranging from 10.44-16.15 years). Slightly more than half (52.2%) were female, half (50%) were people of color, and almost one-fifth (18.8%) were Hispanic.

Measures

The following describes the variables used in this study. The family network indicators were developed for use in the cluster analysis to identify subgroups of youth on socio-ecological dimensions of interest. Next, selected measures were used to describe post-hoc differences and similarities in the characteristics of the groups identified by the cluster analysis. Note that both of these sets of measures were all gathered from baseline data from the SIBS-FC dataset.

Family network indicators

The Essential Youth Experiences (EYE) measure (Kothari et al., 2016) captured youth perceptions of the presence, contact frequency, and quality of their relationships with biological parents, foster caregivers, and the younger sibling in the study. Youth also reported on family members (e.g., biological relatives, step-relatives, adoptive relatives, or otherwise-related) they lived with or were in contact with (at least a few times a year), as well as any non-relatives in the foster home. To determine which variables to include in the profile analysis, network-related indicators were conceptually identified as existing or calculable measures of network structure (size, interconnection), composition, and relationship characteristics. To develop the set of potential indicators, youth-identified relationships were coded by roles (e.g., biological aunt, step-father, non-relative foster parent) which were then aggregated by compositional category (biological adult, biological youth, other related adult or youth, foster adult or youth), and by contact frequency (e.g., same household, in person contact at least monthly, any contact in past few months). Individual (foster adults in household) and combined (foster adults and youth in household) category counts were computed to describe compositional dimensions. These were then aggregated as global indicators (all adults and youth in household) to describe network size independent of composition. Youth specifically reported relationship quality on a scale of 1 (“not good at all”) to 10 (“very good”) for their foster parent(s), biological mother and father, and their sibling in the study.1 29 initial variables were reduced to 11 indicators using exploratory factor analysis.2 Table 2 shows the set of indicators reflecting the dimensions of network size, composition, and relationship quality included in the cluster analysis.

Table 2. Network Indicators.

| Mean (SD) | Range | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Family network size (bio/step/adopt/other, adults or youth, lives with or in contact) | 5.97 (3.44) | 0-18 | 1 | 16 |

| Foster household size (adults/youth lives with) | 4.50 (2.13) | 0-12 | 1 | 12 |

| Family members in foster household | 2.23 (2.29) | 0-12 | 0 | 12 |

| Bio-Relative Adults in foster household | .64 (1.04) | 0-5 | 0 | 5 |

| Bio-Relative Youth in foster household | 1.47 (1.51) | 0-9 | 0 | 4 |

| Non-Relative Foster Adults in foster household | 1.30 (1.12) | 0-5 | 0 | 4 |

| Non-Relative Foster Youth in foster household | .95 (1.44) | 0-9 | 0 | 7 |

| Family members (bio/step/adopt/other) in contact | 3.78 (2.53) | 0-15 | 0 | 15 |

| Relationship quality with bio mom | 5.71 (4.45) | 0-10 | 0 | 10 |

| Relationship quality with bio dad | 3.11 (4.35) | 0-10 | 0 | 10 |

| Relationship with foster parent(s) | 8.45 (1.99) | 1-10 | 1 | 10 |

Note. For relationship quality with biological parents, 0 = no contact (to reduce missing data in the analysis), 1 = not good at all, and 10 = very good. For foster parent relationship quality, 1 = not good at all, and 10 = very good (if youth reported on two foster parent relationships, the quality indicator reflects the mean of these ratings).

Validation measures

The following measures were used to validate the network profiles in this study, including personal and placement characteristics, as well as youth- and caregiver-reported measures. The youth- and caregiver-reported outcome measures were chosen because the existing literature has established a link between youth's social ecology (i.e., their network size/composition) and their mental health functioning (e.g., Cushing et al., 2014; Perry, 2006).

Personal characteristics included age at baseline, gender, race (dichotomous measure of white or persons of color), ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic) and quality of relationship with sibling. Placement characteristics include kinship placement status (i.e., kin or non-kin) and whether the youth lived in same placement with sibling (i.e., together or apart).

The youth-reported outcome instruments included the Quality of Life-Surveillance (YQOL-S, Topolski, Edwards & Patrick, 2002), the Hopelessness Scale for Children (HSC; Kazdin, Rodgers & Colbus, 1986), and the Children's Report of Post-traumatic Stress Symptoms (CROPS; Greenwald & Rubin, 1999).

The YQOL-S is an 8-item youth reported scale designed to assess the youth's self-perceived quality of life. The score is calculated by converting the item scores into t-scores, and then taking a mean score of the t-scores. A higher score indicates a higher quality of life (e.g., I feel good about myself; I feel life is worthwhile). The YQOL-S had good internal consistency in the SIBS-FC sample (OS α=.78; YS α=.73).

The HSC is a 17-item youth-reported scale designed to capture youth's sense of hopelessness. The items (e.g., I will have more good times than bad times; When things are going badly, I know that they won't be as bad all of the time) consist of true/false questions that are then summed, with higher overall values denoting greater feelings of hopelessness. The HSC scale demonstrated good internal consistency in the SIBS-FC sample (OS α=.78; YS α=.75).

The CROPS is a 28-item youth-reported measure designed to assess the prominent symptoms of child trauma. Items (e.g., I feel all alone) are scored on a 0-2 point scale and then summed. A cutoff point of 19 is suggested as having clinical significance. The CROPS demonstrated strong internal consistency in this sample (OS α=90; YS α=88).

Caregiver-reported outcome focused instruments included the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991) and Parent Report of Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms (PROPS; Greenwald & Rubin, 1999). The CBCL for children 6-18 is a parent-reported measure designed to assess behavior problems of youth (e.g., Feels or complains no one loves him/her). It has been widely used with child welfare populations and other at-risk and normative populations. In the SIBS-FC study, the measure was completed by the primary foster caregiver and demonstrated strong internal consistency for the total problem scale (OS α=97; YS α=97).

The PROPS is a 30-item parent-reported measure to assess prominent symptoms of child trauma. Items (e.g., clings to adults) are scored on a 0-2 point scale and then summed. The PROPS scale showed good internal consistency in the full SIBS-FC sample (OS α=93; YS α=93).

Data Analysis

K-means cluster analysis was used to estimate a parsimonious number of distinct groups of foster youth networks. Cluster analysis iteratively groups cases to reduce within-group variance and increase between-group variance. There are multiple hierarchical clustering algorithms that can be used for different descriptive purposes (Borgen & Barnett, 1987; Kaufmann & Rousseeuw, 2009), where the resulting number of groups is often determined by the pre-set number of iterations. Alternatively, k-means cluster analysis iteratively groups cases until it reduces within-group variance and increases between-group variance as much as possible for a pre-set number of groups. This approach may be chosen when the purpose is to use selected indicators to describe substantively relevant groups in a way that explains as much variance as possible without losing interpretability by having too many groups or by having groups that are incomparably-sized.

Because this pre-determination impacts how the clustering algorithm groups cases, it is important to evaluate whether the solution represents a reasonable number of clusters for the dataset. There is no model statistic for k-means cluster analysis, although there are some recommended rules-of-thumb. The “elbow method” is one way to evaluate the variance explained by a cluster solution. The k-means algorithm assigns cases to the pre-set number of clusters and then iteratively re-assigns these to minimize the within-groups variance relative to the total variance (therefore increasing between-groups variance). Because a one-cluster solution does not explain any between-groups variance and an n-cluster solution explains all between-groups variance, the “elbow” in the within-groups variance represents the start of diminished returns on additional variance explained by adding more clusters.

For these data, the inflection point was at 5 clusters, indicating that each cluster added after 5 explained less and less additional variance. The reported 5-cluster solution explained 55% of the variance in the indicators. The suitability of a 5-cluster solution for these data also aligned with interpretability, in that a 4-cluster solution was less distinct, which made it difficult to describe group differences, and the 6-cluster solution was too distinct, such that indicators that were less substantively meaningful (e.g., number of foster youth lives with) would split one cluster into two that were much smaller than the others.

A cluster solution can also be evaluated by whether the clusters are grouping on the variables of substantive interest. The k-means cluster analysis produces an F-test statistic for use in interpreting which indicators determined the cluster solution (in combination with all others) by contributing to mean differences between clusters. This test was statistically significant at p=.000 for all variables except two: the count of non-relative youth in the household; and the quality of the relationship with foster parent(s).

Lastly, cluster assignments were used in separate analysis of variance tests of the youth-reported outcomes (e.g., CROPS, YQOL-S) and caregiver-reported outcomes (e.g., CBCL total score, PROPS). These ANOVAs sought to examine whether the five groups identified by the cluster analysis were significantly different on average in their mental health profiles.

Results

The following section describes the groups produced by the cluster analysis in terms of the indicators used to create the family network profiles. Next we report findings from the post-hoc analysis of demographic and mental health outcome differences between the groups.

Cluster Analysis

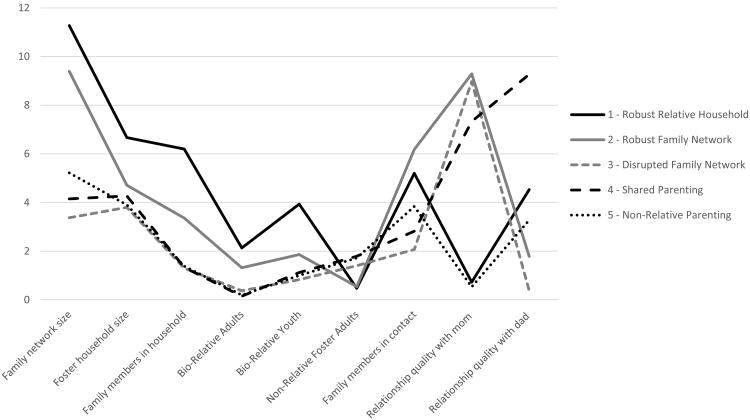

Table 3 shows the cluster group means for the 5-cluster solution produced in the analysis, also illustrated in Figure 1. Five cases were excluded from the cluster analysis due to missing data on one of the clustering variables (n=138). One of the first ways to validate the clusters is substantive interpretability (i.e., face validity). As shown in Table 3, the clusters represent distinct subgroups of youth with different socio-ecological profiles. These groups are summarized as follows from the youth perspective, and are described below in detail.

Robust Relative Household (n=15, 11%) – lives with the most related caregivers and related youth in the largest households, in contact with many additional family members beyond the foster household, moderately good relationship with father

Robust Family Network (n=28, 20%) – lives with a related caregiver and related youth in large households, in contact with the most family members beyond the foster household, very good relationship with mother

Disrupted Family Network (n=30, 22%) – lives with a non-relative caregiver and may live with sibling in the smallest households, very good relationship with mother, but has the least contact with father or other family members

Shared Parenting (n=33, 24%) – lives with non-relative caregivers and sibling in small households, very good relationships with both parents, but in contact with the fewest other family members

Non-Relative Parenting (n=32, 23%) – lives with non-relative caregivers and may live with sibling in small households, low-quality or absent relationships with both parents, but in contact with some other family members

Table 3. Final Cluster Centers.

| 1 - Robust Relative Household (n=15) | 2 - Robust Family Network (n=28) | 3 - Disrupted Family Network (n=30) | 4 - Shared Parenting (n=33) | 5 -Non-Relative Parenting (n=32) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family network size | 11.27 | 9.39 | 3.37 | 4.15 | 5.22 |

| Foster household size | 6.67 | 4.71 | 3.80 | 4.27 | 3.90 |

| Family members in foster household | 6.20 | 3.36 | 1.30 | 1.33 | 1.38 |

| Bio-Relative Adults in foster household | 2.13 | 1.32 | .37 | .15 | .19 |

| Bio-Relative Youth in foster household | 3.93 | 1.86 | .83 | 1.12 | 1.00 |

| Non-Relative Adults in foster household | .47 | .54 | 1.40 | 1.79 | 1.72 |

| Non-Relative Youth in foster household* | .00 | .82 | 1.10 | 1.15 | .81 |

| Family members in contact | 5.20 | 6.18 | 2.07 | 2.82 | 3.84 |

| Relationship quality with bio mom | .73 | 9.29 | 8.97 | 7.33 | .53 |

| Relationship quality with bio dad | 4.53 | 1.78 | .37 | 9.27 | 3.28 |

| Relationship with foster parent(s)* | 9.13 | 7.89 | 8.63 | 8.45 | 8.73 |

Not a significant clustering variable

Figure 1. Final cluster centers.

In the Robust Relative Household group (Cluster 1, n=15), youth generally lived with two biologically-related adults and multiple related youth (e.g., siblings, cousins), resulting in the largest reported households. Youth in this group also reported many additional family members (biological, step-, adoptive, or otherwise-related) that they were in contact with outside the foster household, resulting in the largest family networks overall. These youth reported relatively good relationships with their biological father (M=4.53, SD=5.03) compared to most of the other groups, but also reported either no contact or very low relationship quality with their biological mothers (M=0.73, SD=1.94).

Conversely, in the Robust Family Networks subgroup (Cluster 2, n=28), youth had relatively large family networks overall, and were living with one or two related adults and one or two related youth. These youth reported the most additional family members that they were in contact with beyond the household, and these youth reported excellent relationships with their biological mothers on average (M=9.29, SD=1.17), and relatively poor or inactive relationships with their biological fathers (M=1.18, SD=2.91).

These first two family constellation profiles, the smallest clusters overall, indicate relatively plentiful kinship-oriented networks with the resources to provide a relative foster placement and to help youth maintain connections to additional family members, including at least one biological parent. The primary distinction between these two subgroups is whether the youth report having an active and positive relationship with their biological mother or with their biological father.

The three remaining clusters had comparatively small family constellations and youth were more likely to be living with one or more non-relative caregivers. For the first of these, named the Disrupted Family Network (Cluster 3, n=30), youth assigned to the group reported excellent relationships with their biological mothers and no contact or very poor relationships with their biological fathers. However, unlike the more robust family-based profiles described above, youth in this subgroup were likely to be living with one non-relative foster parent and were least likely to be living with more than one related youth, and they reported being in contact with the fewest family members overall, resulting in the smallest family networks overall.

Similarly, youth in the Shared Parenting subgroup (Cluster 4, n=33) were likely to be living with two non-relative caregivers and one other related youth on average, and they were in contact with relatively few biological family members, resulting in relatively small family networks overall. Notably, however, this group reported having very good relationships with their biological mothers and excellent relationships with their biological fathers, resulting in youth-reported relationships with at least four total parent-figures.

Lastly, youth in the Non-Relative Parenting group (Cluster 5, n=32) were living with two non-relative caregivers and with one related youth on average. Youth in this group were in contact with some family members outside the foster home. However, it is notable in that the youth in this group reported very poor or inactive relationships with their biological mothers (M=0.53, SD=1.30), and poor relationships with their fathers (M=0.28, SD=1.11).

Differences by Cluster Assignment

As shown in Table 4, the cluster assignments were not associated with youth age, gender, or race. There were differences by whether the youth lived in relative care (x2=45.483, p=.000), where 87% of Cluster 1 (Robust Relative Household) was living with kin, compared to 16% of Cluster 5 (Non-Relative Parenting). There were also differences by whether youth lived with their sibling (recalling that all youth in sample had at least one younger sibling who was also in care), where 93% of the sibling pairs were placed together in Cluster 1, compared to 60% in the Disrupted Family Network Cluster 3 (x2=9.974, p=.041). There was not a difference in relationship quality with the sibling by cluster group.

Table 4. Differences in Personal and Placement Characteristics and Outcomes by Cluster Groups.

| Sample (N=138) | 1 - Robust Relative Household | 2 - Robust Family Network | 3 - Disrupted Family Network | 4 - Shared Parenting | 5 - Non-Relative Parenting | F (4, 133) or x2 (4) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 13.01 | 12.77 | 12.97 | 13.04 | 13.20 | 12.93 | .263 | .901 |

| Gender (% female) | 52.2% | 66.7% | 42.9% | 66.7% | 42.4% | 50.0% | 6.080 | .193 |

| Race (% persons of color) | 50.0% | 60.0% | 46.4% | 40.0% | 54.5% | 53.1% | 2.341 | .673 |

| Lives in relative care | 36% | 87% | 71% | 20% | 18% | 16% | 45.483 | .000 |

| Lives with sibling | 73% | 93% | 86% | 60% | 76% | 63% | 9.974 | .041 |

| Relationship with Sibling (1-10) | 7.62 | 8.33 | 7.46 | 7.07 | 7.85 | 7.69 | .890 | .472 |

| Youth-reported quality of life (YQOL-S) | 82.2 | 83.33 | 86.77 | 79.81 | 84.89 | 77.23 | 1.614 | .175 |

| Youth-reported hopelessness (HSC) | 30.17 | 32.13 | 28.86 | 29.63 | 30.03 | 31.00 | .626 | .645 |

| Parent-reported trauma symptoms (PROPS) | 15.64 | 10.864 | 10.964 | 17.19 | 20.681,2 | 15.63 | 4.040 | .004 |

| Parent-reported behavior problems (CBCL) | 60.38 | 59.43 | 61.79 | 60.75 | 61.84 | 57.71 | .625 | .645 |

Note. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for statistically significant group differences on the four outcome variables, with a Tukey post-hoc test for individual group differences (shown with subscripts referring to the category columns in the order listed in the table). Given the number of statistical tests, a Bonferroni correction for Type I error rate would be p < .0125.

Among the validation measures tested, there were no statistically significant differences by cluster assignment, with the exception of the caregiver reported post-traumatic stress symptoms (PROPS; F=4.040, p=.004). Specifically, the three groups (Clusters 3-5) that were not distinguished by a robust kinship network had caregiver reports of post-traumatic stress that were at least 50% higher than the two relative-based clusters (Clusters 1-2). Although there were no differences by cluster on the demographic variables, follow-up sensitivity tests were conducted (via MANCOVA) to test for cluster-based differences on each of the validation measures of youth mental health symptomatology, controlling for differences in youth age, race, and gender. These tests were not statistically significant and did not alter the ANOVA-based findings displayed in Table 4.

Discussion

The present study contributes to the small set of studies describing the social ecology of youth in foster care. Drawing upon secondary analyses of a unique study of pre-adolescent and adolescent youth in foster care, the current study identifies patterns in the size, composition, and strength of relationships reported by youth in foster home placements, including with foster parents, biological parents, and other relatives. Although researchers interested in the social context of youth experiences while in foster care have begun taking a more socioecological or social network perspective, studies to date have focused primarily on functional measures of social support, including the presence of particular relationships of interest (e.g., natural mentors). In contrast, network-focused questions pertaining to the overall social context within which youth in foster care are embedded—including those concerned with social network composition, interconnection between network members (or network density), and network member stability—have not been addressed to date in empirical research (Blakeslee, 2012).

In focusing on these dimensions of youth-perceived networks, this study first used cluster analysis to identify distinct groups of youth based on network characteristics; and then validated these groups in reference to personal characteristics, placement factors, and psychosocial outcomes. In so doing, the current study explored the underlying heterogeneity in the social ecology of foster youth in fostering households and tested for linkages between youth networks and outcomes of interest to policymakers and practitioners (e.g., placement with relatives and co-placement with siblings, and mental health and posttraumatic stress symptomology).

Findings based on youth reports of family network characteristics suggested the existence of distinct groups of youth. Descriptive group profiles highlighted the combination of social resources that were available for youth in foster home settings in terms of network indicators accounting for the potential complexity of these family constellations. Indicators also reflected network dimensions identified in previous studies to be of importance. Specifically, the chosen indicators: attended to the possible presence of kin beyond biological relatives in the family network size measure; accounted for family members (i.e., adults and youth) in foster households as well as non-family members; and reflected the number of family members with whom youth were in contact. Two indicators—non-relative youth in the household, and relationship quality with foster parents—did not uniquely contribute to the assignment of youth to the cluster groups.

The clusters that aligned with relative placement and placements with siblings also aligned with caregiver reports of youth post-traumatic stress. In the Robust Relative Household and Robust Family Network constellations, youth appeared to have access to a stable, family-based core of interconnected relationships involving multiple youth and adults. From a network perspective, this may suggest that these youth were embedded within a social setting in which adults had some capacity to effectively monitor and provide for youth needs, including maintaining important positive relationships with at least one biological parent. It is also possible that these networks were structured to resist disruption, such that if one member left the immediate network—e.g., if a parent with whom the youth had a strong relationship was incarcerated—the remaining members could be expected to maintain communication and support between the youth, the absent adult, and others. These two profiles illustrate how relative placement or kinship care can be seen as a mechanism to keep youth connected to a larger family-based network comprised of previously established network relationships, as well as to the youth's non-custodial biological parents (Kiraly & Humphries, 2013; 2015).

The other three clusters, with fewer reported family members in the household or otherwise in contact with the focal youth, appeared to represent social contexts in which there were weaker family-based relationships, as understood in terms of network size and relationship quality. The Shared Parenting cluster was notable for the number of caregivers available to youth, including both biological parents and two non-relative foster parents, which may suggest there could be less focus on maintaining additional family relationships while the youth was in placement. The remaining two profiles—Disrupted Family Network and Non-Relative Parenting—are more concerning, in that the overall support capacity of the youth-reported network appeared limited. These latter constellations reflected an emphasis on non-relative foster placements for primary caregiving, with absent or low-quality connections to one or both biological parents and relatively few other family members named in the network. Additionally, though all youth in this study had a younger sibling who was also in care, youth in these subgroups were least likely to be placed with that sibling. Such youth-reported family constellations may reflect network disruption related to youth placement into foster care; they also may reflect settings where familial resources are limited.

Relatedly, the increased caregiver report of PTSD symptoms in these three clusters may imply a higher risk of further network disruption for these youth. It may be that this finding reflects fewer symptoms in less disrupted family networks. However, it is also possible that relative caregivers perceived such symptoms differently as compared to non-family caregivers, who may have been less aware of youth mental health needs, and as a result, may be less likely to normalize youth behavior. The finding of group-based differences in PROPS scores requires further exploration, particularly as compared to the other outcomes examined in relation to group membership that were found to not be significantly different across groups.

More broadly, the three clusters that were not characterized by larger relative-based networks reflect important variation in youth perceptions of their proximal networks and ongoing family connections. For example, those in the Shared Parenting group reported good relationships with four biological and foster parent figures on average. It is conceivable that having this parenting support function spread across multiple parent figures in adolescence may be an important contributor to longer-term well-being in early adulthood (Cushing et al., 2014). In the other two non-relative clusters—Disrupted Family Network and Non-Relative Parenting— it is concerning that there exist indicators that important family relationships had not been maintained or replaced by new network members. In these groups, future research may examine whether the presence or absence, strength, and consistency of these relationships are associated with psychological well-being following the network disruption of foster placement (Perry, 2006). Further, these profiles prompt consideration of the roles relative and non-relative caregivers play in preventing further network disruption by linking youth to larger kin networks, including non-custodial biological parents where possible, to support the maintenance of strong social bonds for youth (Beihal, 2012; Hedin, 2014; Holtan, 2008; Negriff et al., 2015).

Study Limitations

These findings, and the conclusions derived from them, should be understood in relation to a number of study limitations. First, due to the secondary nature of the study, the indicators comprising the family constellations were limited in important ways. More precise indicators of network membership—including measures of the consistency of critical relationships over time—were unavailable. Nor were measures of network composition available from the perspective of other key individuals. Although the development of youth-centered ego networks is a critical initial step in understanding the social ecology of foster youth, youth perspectives should ideally be supplemented with the perspectives of key individuals in the network so as to avoid reporting bias and permit more refined analyses testing for reciprocal ties between youth and others. Second, although the SIBS-FC study from which data were drawn involved an RCT, the current study reflected analyses of cross-sectional data. As a result, statistically significant relationships between cluster membership and personal, placement, and psychosocial outcomes should be understood to be relational as opposed to causal. Relatedly, this is a smaller subsample drawn from the original study and further reduced to older siblings only, which is a limitation given the relatively exploratory nature of the current analyses. Finally, although the study sample included large proportions of youth of color (non-Caucasian) as well as siblings in foster care, study data were drawn from a 3-county metropolitan region of Oregon. Additionally, selection criteria from the original RCT from which this subsample was drawn may have resulted in selection bias. Specifically, youth may have been more likely to participate in both the parent study and in the current investigation if they had been in more stable placements than might be found in the general foster youth population. Such selection bias, if present, might have limited the underlying heterogeneity in the study sample by reducing the range of scores between clusters and increasing the likelihood that indicator scores were high. For these reasons, generalizability to other child welfare populations and jurisdictions may be limited.

Implications and Conclusion

Notwithstanding these limitations, study findings have implications for child welfare practice and research. Our results suggest that common indicators of placement quality in foster care, including co-placement with relatives and/or siblings, may co-vary in non-obvious ways with measures of the quality, consistency, and stability of the critical relationships between youth and other key individuals. It should not be assumed, for example, that placing a youth in a kinship setting will result in the level of relational permanence that undergirds current federal and state child welfare policies preferring relative placement over non-relative foster care. More generally, study findings highlight the importance of assessing opportunities for youth to receive social support from foster parents as well as family members regardless of whether they are placed with kin or siblings, or if they remain in stable home-like settings. However, such ongoing assessment of the availability of social resources may be especially important for youth who are not placed with sibling(s) or relatives, and/or those who do not have identified connections to family members outside their foster placement. It is these youth who may have the greatest need for social ecological interventions, and who may be at greatest risk of experiencing poor permanency and wellbeing outcomes.

Finally, the current study reinforces the importance of conducting research on the social ecology of youth in the foster home setting. The manner in which youth integrate into the foster family, the proximal networks of adults and youth connected to the home, and the perceptions of youth as to the degree of support they are afforded within and beyond the home are important topics for future research. So too are questions pertaining to change vs. consistency in the relationships youth have with relatives including siblings and non-relatives, particularly in relation to the dynamic social and mental health needs of youth. Such research may go beyond the focus of the current study on network size and composition, and may benefit from attention to other social network concepts such as social norms, reciprocal ties, embeddedness, and network centrality. Ideally, research would be conducted (as in the current study) by focusing first upon the ego network centered upon the perspective of youth. The development of a body of studies on these topics should improve our understanding of the manner in which youth are integrated effectively and supported consistently while in foster care.

Highlights.

Foster youth reported on their current household composition and family networks.

Cluster analysis identified family network profiles within and beyond foster homes.

Two profiles reflect relative placements and robust family networks.

Three profiles show fewer family connections within or beyond the foster home.

Profiles showed differences in caregiver reports of post-traumatic stress symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Research support is gratefully acknowledged from the National Institute of Mental Health for the project, 'Evaluation of Intervention for Siblings in Foster Care,' (R01 MH085438, Lew Bank, PI). The information reported herein reflects solely the positions of the authors.

Footnotes

Note that for relationship quality with biological parents, “no contact” was coded as “0” on the 10-point scale, toreduce missing data in the analysis (given that many youth had no contact with one or both parents). If youthreported on two foster parent relationships, the quality indicator reflects the mean of these.

For example, there were counts for biological relatives youth were (1) living with, or (2) in contact with, and therewere similar counts for other relatives. We include a combined count of all of these as a family network sizeindicator, but also the count of biological relatives they were living with, as these were each factors in the EFA.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Blakeslee, Portland State University

Brianne H. Kothari, Oregon State University

Bowen McBeath, Portland State University

Paul Sorenson, Portland State University.

Lew Bank, Portland State University

References

- Aarons GA, James S, Monn AR, Raghavan R, Wells RS, Leslie LK. Behavior problems and placement change in a national child welfare sample: A prospective study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(1):70–80. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201001000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: Dept of Psychiatry. University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barber JG, Delfabbro PH. Placement stability and the psychosocial well-being of children in foster care. Research on Social Work Practice. 2003;13(4):415–431. [Google Scholar]

- Berrick JD, Hernandez J. Developing consistent and transparent kinship care policy and practice: State mandated, mediated, and independent care. Children and Youth Services Review. 2016;68(1):24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Biehal N. A sense of belonging: Meanings of family and home in long-term foster care. British Journal of Social Work. 2012;44(4):955–971. [Google Scholar]

- Blakeslee J. Expanding the scope of research with transition-age foster youth: Applications of the social network perspective. Child & Family Social Work. 2015;17:326–336. [Google Scholar]

- Blakeslee J. Measuring the support networks of transition-age foster youth: Preliminary validation of a social network assessment for research and practice. Children and Youth Services Review. 2015;52:123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Borgen FH, Barnett DC. Applying cluster analysis in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1987;34(4):456. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Bank LI. Toward an integration of macro and micro measurement systems for the researcher and the clinician. Journal of Family Psychology. 1989;3(2):199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Hook JL, Lee JS. Distinct subgroups of former foster youth during young adulthood: Implications for policy and practice. Child Care in Practice. 2012;18(4):409–418. [Google Scholar]

- Cushing G, Samuels GM, Kerman B. Profiles of relational permanence at 22: Variability in parental supports and outcomes among young adults with foster care histories. Children and Youth Services Review. 2014;39:73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Degenne A, Lebeaux M. The dynamics of personal networks at the time of entry into adult life. Social Networks. 2005;27(4):337–358. [Google Scholar]

- Earls F, Carlson M. The social ecology of child health and well-being. Annual Review of Public Health. 2001;22(1):143–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingsen IT, Stephens P, Størksen I. Congruence and incongruence in the perception of ‘family’ among foster parents, birth parents and their adolescent (foster) children. Child & Family Social Work. 2012;17(4):427–437. [Google Scholar]

- Etzion D, Romi S. Typology of youth at risk. Children and Youth Services Review. 2015;59:184–195. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer E. How do placements in kinship care compare with those in non-kin foster care: placement patterns, progress and outcomes? Child & Family Social Work. 2009;14(3):331–342. [Google Scholar]

- Fox A, Berrick JD, Frasch K. Safety, family, permanency, and child well-being: What we can learn from children. Child Welfare. 2008;87(1):63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner H. The concept of family: Perceptions of children in family foster care. Child Welfare. 1996;75161(2) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald R, Rubin A. Assessment of posttraumatic symptoms in children: Development and preliminary validation of parent and child scales. Research on Social Work Practice. 1999;9(1):61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hedin L. A sense of belonging in a changeable everyday life-a follow-up study of young people in kinship, network, and traditional foster families. Child & Family Social Work. 2014;19(2):165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Holtan A. Family types and social integration in kinship foster care. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30(9):1022–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman L, Rousseeuw PJ. Finding groups in data: an introduction to cluster analysis. Vol. 344. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Rodgers A, Colbus D. The Hopelessness Scale for Children: Psychometric characteristics and concurrent validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54(2):241–245. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller TE, Cusick GR, Courtney ME. Approaching the transition to adulthood: Distinctive profiles of adolescents aging out of the child welfare system. The Social Service Review. 2007;81(3):453. doi: 10.1086/519536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiraly M, Humphreys C. Perspectives from Young People about Family Contact in Kinship Care: “Don't Push Us—Listen More”. Australian Social Work. 2013;66(3):314–327. [Google Scholar]

- Kiraly M, Humphreys C. A tangled web: parental contact with children in kinship care. Child & Family Social Work. 2015;20(1):106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kothari BH, McBeath B, Lamson-Siu E, Webb SJ, Sorenson P, Bowen H. Development and feasibility of a sibling intervention for youth in foster care. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2014;47:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothari BH, McBeath B, Bank L, Sorenson P, Waid J, Webb SJ. Validation of a measure of foster home integration for foster youth. Research on Social Work Practice. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1049731516675033. 1049731516675033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothari BH, McBeath B, Sorenson P, Bank L, Waid J, Webb SJ, Steele J. An intervention to improve sibling relationship quality among youth in foster care: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2017;63:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett S, Rosenthal D, Myers P, Milburn N, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Practising homelessness: a typology approach to young people's daily routines. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27(3):337–349. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBeath B, Kothari BH, Blakeslee J, Lamson-Siu E, Bank L, Linares L, Shlonsky A. Intervening to improve outcomes for siblings in foster care: Conceptual, substantive, and methodological dimensions of a prevention science framework. Children and Youth Services Review. 2014;39:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt DH. Placement preferences among children living in foster or kinship care: A cluster analysis. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30(11):1336–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Milburn N, Liang LJ, Lee SJ, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Rosenthal D, Mallett S, et al. Lester P. Who is doing well? A typology of newly homeless adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;37(2):135–147. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D, Neal M, Carder P. The stability of core and peripheral networks. Social Networks. 1996;9(1):9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Negriff S, James A, Trickett PK. Characteristics of the social support networks of maltreated youth: Exploring the effects of maltreatment experience and foster placement. Social Development. 2015 doi: 10.1111/sode.12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton RR, Litrownik AJ, Landsverk JA. Children and youth in foster care: Disentangling the relationship between problem behaviors and number of placements. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24(10):1363–1374. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry BL. Understanding social network disruption: The case of youth in foster care. Social Problems. 2006;53(3):371–391. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett R, Gillberg C, Minnis H. What do child characteristics contribute to outcomes from care: A PRISMA review. Children and Youth Services Review. 2013;35(9):1333–1341. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DM, O'Reilly AL, Luan X, Localio AR. The impact of placement stability on behavioral well-being for children in foster care. Pediatrics. 2007;119(2):336–344. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. We know some things: Parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Storer HL, Barkan SE, Stenhouse LL, Eichenlaub C, Mallillin A, Haggerty KP. In search of connection: The foster youth and caregiver relationship. Children and Youth Services Review. 2014;42:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topolski TD, Edwards TC, Patrick DL. User's manual and interpretation guide for the Youth Quality of Life (YQOL) Instruments. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Department of Health Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children's Bureau. 2012 http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb.

- Walker M, Wasserman S, Wellman B. Statistical models for social support networks. Sociological Methods & Research. 1993;22(1):71. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman B, Gulia M. The network basis of social support: A network is more than the sum of its ties. In: Wellman B, editor. Networks in the Global Village: Life in Contemporary Communities. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1999. pp. 83–118. [Google Scholar]

- Yampolskaya S, Sharrock P, Armstrong MI, Strozier A, Swanke J. Profile of children placed in out-of-home care: Association with permanency outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review. 2014;36:195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Yates TM, Grey IK. Adapting to aging out: Profiles of risk and resilience among emancipated foster youth. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24(2):475–492. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinn A. A typology of kinship foster families: Latent class and exploratory analyses of kinship family structure and household composition. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32(3):325–337. [Google Scholar]