Abstract

We evaluated five competing hypotheses about what predicts romantic interest. Through a half-block quasi-experimental design, a large sample of young adults (i.e., responders; n = 335) viewed videos of opposite-sex persons (i.e., targets) talking about themselves and responders rated the targets’ traits and their romantic interest in the target. We tested whether similarity, dissimilarity, or overall trait levels on mate value, physical attractiveness, life history strategy, and the Big-Five personality factors predicted romantic interest at zero acquaintance, and whether sex acted as a moderator. We tested the responders’ individual perception of the targets’ traits, in addition to the targets’ own self-reported trait levels and a consensus rating of the targets made by the responders. We used polynomial regression with response surface analysis within multilevel modeling to test support for each of the hypotheses. Results suggest a large sex difference in trait perception; when women rated men, they agreed in their perception more often than when men rated women. However, as a predictor of romantic interest, there were no sex differences. Only the responders’ perception of the targets’ physical attractiveness predicted romantic interest; specifically, responders’ who rated the targets’ physical attractiveness as higher than themselves reported more romantic interest.

Keywords: Attraction, Social Relations Model, Trait Perception, Big-Five Personality Factors, Life History Strategy, Mate Value, Polynomial Regression, Response Surface Analysis, Multilevel Model

Attraction to a person during an initial encounter is traditionally the first step in any beginning romantic relationship. Theoretically and empirically, researchers have proposed a variety of traits and mechanisms by which initial attraction operates. These include the potential partner’s traits, such as his or her personality (e.g., Klohnen & Luo, 2003), and physical appearance, such as his or her physical attractiveness (e.g., Buss & Schmitt, 1993). Theoretically, researchers have proposed individuals are attracted to someone who is similar (e.g., Bryne, 1997), dissimilar (e.g., Aron & Aron, 1986), or has high values on socially desirable traits (e.g., Walster, Aronson, Abrahams, & Rottman, 1966), and that sex may moderate which traits predict attraction (e.g., Buss & Schmitt, 1993), and the extent to which one directs attention towards perceiving a particular trait, with traits that are perceived predicting attraction (Fisher, 1930).

In this paper, we apply the Method of Multiple Working Hypotheses (Chamberlin, 1890) and with inclusive statistical models evaluate five competing hypotheses about what predicts attraction. In line with recommendations from Schimmack (2012), and more recently Finkel, Eastwick, and Reis (2015), instead of presenting results from several studies with relatively small sample sizes (e.g., 80 subjects, which is the median sample size of most relationship research), we present an exhaustive study based on one relatively large sample size (n = 335). This larger sample size decreases the likelihood that the statistically based inferences are due to Type I errors while simultaneously decreasing the likelihood of Type II errors, partially due to the more stable parameter estimates, but also because of the increased statistical power. Because the mechanism of attraction may operate differently depending on the trait studied, the hypotheses will be evaluated for a variety of individual difference traits. In addition, we apply trait perception theory to estimate the extent to which the traits were reliably detected in our study and whether this differs between the sexes, informing decisions surrounding the expected influence of the traits on attraction. Finally, because the hypotheses differ depending on whether they are describing individual perception of a potential partner’s trait levels, the potential partner’s actual trait levels, or both, we will test the extent to which these hypotheses apply to three measures of the potential partners’ traits (described in detail below).

First, we introduce five broad hypotheses, and their empirical support, regarding predictors of romantic attraction, which present competing hypotheses as to the primary predictor of attraction. The first two hypotheses propose potential partners are evaluated relative to oneself, with the goal of finding someone similar (Hypothesis 1) or dissimilar (Hypothesis 2). The next three hypotheses propose that an evaluation of a potential romantic partner is done independent of one’s self-concept, and instead individuals are attracted to persons high on socially desirable traits (Hypothesis 3), which is moderated by one’s sex ( Hypothesis 4), and that only those traits that are perceived predict romantic interest (Hypothesis 5). Each is discussed in turn in the next section.

Predictors of Attraction: Five Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1: Similarity predicts attraction

Bryne’s (1997) attraction paradigm proposes that the perception of similarity in attitudes with a potential partner leads to greater attraction to that person. He described a weighted ratio of reinforcements and punishments, whereby reinforcements come from perceiving similarity and punishments come from perceiving dissimilarity, and identified a linear relation between the proportion of similar attitudes and attraction (Bryne & Nelson, 1965). Similarly, researchers have argued that individuals select for someone phenotypically similar, with the goal of attaining a partner genetically similar (except to the point of incest; Rushton, 1989) in what is referred to as assortative mating (Buss, 1985).

Research suggests that when individuals are asked about their ideal romantic partner, they prefer someone who is similar on the attachment dimensions (Holmes & Johnson, 2009), and the Big-Five personality factors (Figueredo, Sefcek, & Jones, 2006). Hitsch, Hortaçsu, and Ariely (2010), in a study examining the behavior of online dating users, found that individuals were more likely to initiate contact with someone who was similar to themselves on education, ethnicity, marital status (i.e., single versus divorced), parental status, religion, political views, and smoking. Finally, romantic couples have been found to be assortatively mated on a variety of characteristics and traits including age, religion, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (Buss, 1985), height, hair and eye color (Vandenberg, 1972), physical attractiveness (Buss, 1985; Feingold, 1988), intelligence (Mascie-Taylor & Vandenberg, 1988; Keller et al., 1996), the Big-Five personality factors (e.g., Mascie-Taylor & Vandenberg, 1988; Price & Vandenberg, 1980; Watson, Hubbard, and Weise, 2000; cf. Luo & Klohnen, 2005 and Watson et al., 2004), values, political attitudes, religiosity (Luo & Klohnen, 2005; Watson et al., 2004), avoidant attachment (Watson et al., 2004, cf. Luo & Klohnen, 2005), anti-social behavior (Frisell, Pawitan, Langström, & Lichtenstein, 2012), life history strategy, and mate value (e.g., Figueredo & Wolf, 2009; Figueredo, et al., 2015; Olderbak & Figueredo, 2012).

Hypothesis 2: Dissimilarity predicts attraction

The Self-Expansion Model, by Aron and Aron (1986), proposes that greater perceived dissimilarity on attitudes and traits will lead to increased attraction because the dissimilarity will lead to a greater expansion of the self-concept. Winch’s (e.g., 1955, 1967) Theory of Complementary Needs suggested that while couples may be similar on demographic characteristics (e.g., socioeconomic status), successful relations are characteristic of individuals who differ on personality variables (e.g., dominance versus submissiveness).

In the attachment literature, researchers found that individuals with complementary attachment styles (i.e., avoidant with anxious) is more common in couples who remain together (Holmes & Johnson, 2009). Olderbak and Figueredo (2012) found disassortative mating, the phenomenon whereby individuals have a romantic partner who has different or complementary values on phenotypic traits more than would be expected by random pairing, on indicators of the divergent interest strategies construct (Malamuth, 1998). These variables were mating effort (the effort one directs towards attaining and retaining a romantic partner; Rowe, Vazsonyi, & Figueredo, 1997), intentions towards infidelity (the likelihood one would commit an infidelity; Jones, Olderbak, & Figueredo, 2010), and self-monitoring (the extent to which one actively tries to present the most socially appropriate behavior in a given context; Snyder, 1974). Research suggests that individuals disassortatively mate on the smell complex associated with the Major Histocompatibility Complex (e.g., Penn & Potts, 1999), however the results are mixed (Havlicek & Roberts, 2008; Thornhill et al., 2003), and may be moderated, for example, by the population studied (e.g., Chaix, Cao, & Donnelly, 2008).

Hypothesis 3: High (or higher) values on socially desirable traits predicts attraction

The third hypothesis is that individuals are attracted to someone they perceive to be, or who actually is, high on particular traits and/or is relatively higher than themselves. Social Aspiration Theory (Berscheid, Dion, Walster, & Walster, 1971; Walster et al., 1966) proposes that individuals prefer to date someone with a level of social desirability higher than themselves, where social desirability is defined as the sum of an individual’s social assets, such as physical attractiveness, popularity, personableness, and material resources, weighted by importance and salience for others. A comparable theory suggests individuals are attracted to someone high on mate value, which is defined as having high reproductive value (the potential to produce a high number of offspring in his or her lifetime), and high resource holding potential/status (high dominance status in his or her social group aggregated across socially desirable characteristics; Kirsner, Figueredo, & Jacobs, 2003). Research indicates that individuals express a preference for a romantic partner who is physically attractive (e.g., Buss, 1989; Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Trivers, 1972), with this rated especially important for initial attraction (Sprecher, 1998). In addition, individuals express a preference for a romantic partner with a secure attachment style (Holmes & Johnson, 2009), and with high levels on the Big-Five personality factors (Luo & Zhang, 2009), or slightly higher than themselves (Figueredo, Sefcek, & Jones, 2006).

Hypothesis 4: Sex moderates what predicts attraction

Sexual Strategies Theory (Buss & Schmitt, 1993), an extension of Trivers’ (1972) theory of sexual selection and parental investment, proposed that due to differential investment in childrearing, there are quantitative and qualitative differences in approaches towards short and long-term romantic relationships depending on one’s biological sex. Gangestad and Simpson (2000) further expanded these theories by proposing that men and women adjust their strategies depending on environmental circumstances, and that there is considerable variation in the choice of strategies within a sex. However, evidence for an overall effect of sex is often found. Buss’ (1989) large cross-cultural study found that characteristics indicative of resource acquisition (i.e., good financial prospects, ambition, industriousness) are more desired by women in men, whereas characteristics indicative of reproductive capacity (i.e., younger in age, physical attractiveness, chastity prior to the relationship) are more desired by men in women. Finally, there is partial support for sex differences on the effect of a potential partner’s personality on attraction. Furham (2009) found that women, more than men, prefer a romantic partner who is emotionally stable and conscientious, however, he found no sex difference for the other traits.

Hypothesis 5. Readily perceived traits predict attraction

A fifth hypothesis is that only those traits that are readily perceived (i.e., a “good trait” according to Funder’s [1995] Realistic Accuracy Model) will predict romantic interest. Fisher’s (1930) Runaway Sexual Selection theory suggests that in mating systems where females incur greater reproductive costs and hence are more selective in their choice of partners, as is the case for humans (Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Trivers, 1972), any arbitrary female preference for a male trait (i.e., traits that are not necessarily tied to reproductive success), once established in the population, will be sexually selected for by women leading to increasingly exaggerated and otherwise maladaptive versions of that trait in men (e.g., peacock tails). Thus, this theory suggests that women will learn to direct attention towards these traits when considering a man as a potential romantic partner. This process consists of a positive feedback mechanism in population genetics that is generated between selection for the possession of a sexually attractive trait and selection for the preference for that given trait. If a particular sexually selected trait is at least partially heritable, women will inevitably be selected to consider the effects of that trait upon the mating success of their offspring. This theory has been empirically supported in a variety of species of nonhuman animals (e.g., Weatherhead & Robertson, 1979) and research suggests that these female preferences need not be innate; all that is needed is a tendency to “copy” the mating preferences of other females in the population (e.g., White, 2004). This hypothesis was presented in the trait perception literature where researchers found that those traits that were accurately perceived at zero acquaintance (i.e., physical attractiveness, extraversion) were the traits that predicted romantic interest (Fletcher, Kerr, Li, & Valentine, 2014).

Overall, hypotheses 1 to 5 make unique predictions. Hypotheses 1 and 2 predict that variables that measure the comparison of a potential romantic partner relative to oneself will significantly predict romantic interest, with hypothesis 1 proposing similarity predicts romantic interest and hypothesis 2 proposing that dissimilarity predicts romantic interest. Hypotheses 3, 4, and 5 however, predict that interest is not based on a comparison of the potential romantic partner against one’s perspective on him or herself, but instead that a romantic partner is evaluated in comparison with the population of potential romantic partners, with individuals showing more romantic interest in individuals high, or higher than themselves, on particular traits. Hypothesis 4 differs from hypothesis 3 by predicting that the extent to which a potential romantic partner’s overall trait levels predict romantic interest will differ depending on one’s sex, and hypothesis 5 predicts that only those traits that are perceived will predict romantic interest. Hypotheses 4 and 5 should apply only as moderators to hypothesis 3, however we will test sex differences for hypotheses 1 and 2 as well, and indirectly, we test whether hypothesis 5 moderates hypothesis 1 and 2.

Next, we will discuss how these hypotheses were tested.

Current Study

Individual Difference Traits

As a test of the aforementioned hypotheses, we chose a variety of individual difference traits previously identified as influencing romantic attraction or because they are traits on which individuals assortatively mate, specifically the Big-Five personality factors (Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Openness to Experience, Emotional Stability), life history strategy, and mate value estimated with and without physical attractiveness, with physical attractiveness also tested separately. Briefly in support of the inclusion of the Big-Five personality factors, when asked about the personality of one’s ideal romantic partner, participants report interest in a partner who is somewhat similar to themselves, but also somewhat higher (Figueredo, Vásquez, et al., 2006), romantic interest in a potential partner can be predicted by the potential partner’s self-reported trait levels (Luo & Zhang, 2009), and romantic partners tend to be assortatively mated on the Big-Five personality factors (e.g., Price & Vandenberg, 1980). In support of the inclusion of mate value and life history strategy, these are traits on which romantic partners are assortatively mated (Figueredo, et al., 2015), self and partner trait levels have been shown to predict not only current (Olderbak & Figueredo, 2009, 2012) but also future satisfaction in a romantic relationship, in addition to relationship dissolution (Olderbak & Figueredo, 2010), and participants rate their ideal partner’s mate value, for a short or long-term relationship, as similar to their own (Kirsner et al., 2003).

While mate value was defined previously, and the Big-Five personality factors are well-known constructs within the field of psychology, life history strategy is not as well known so we provide a definition here. Life history strategy describes the pattern of trade-offs individuals must make between allocating time and energy towards one’s own survival, attaining and retaining a romantic partner, and taking care of one’s offspring, with person-level scores on a continuum ranging from fast to slow life history strategy (Roff, 1992). Variability between persons has a heritable component (Figueredo, Vásquez, Brumbach, & Schneider, 2004) and can be predicted by one’s environment; individuals raised in a more unpredictable and harsh environment are more likely to develop a fast life history strategy, whereas those from a more predictable and stable environment are more likely to develop a slow life history strategy (Belsky, Steinberg, & Draper, 1991; Ellis, Figueredo, Brumbach, & Schlomer, 2009). A fast life history strategy is associated with reaching puberty at an earlier age and having a more unrestricted sociosexuality while a slow life history strategy is associated with reaching puberty at an older age and having a more restricted sociosexuality (Dunkel & Decker, 2010; Dunkel, Summerville, Mathes, & Kesserling, 2015).

Study Design

Our hypotheses were tested in a half-block quasi-experimental social relations design (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006) and we looked at attraction at zero acquaintance (i.e., a situation where one participant observes another [i.e., target], but never interacts with the target or sees the target interact with someone else; Kenny, 2004). In this design, one set of participants, referred to as the responders, “met” another set of participants, referred to here as the targets, by watching a videotape of the target talk about him or herself. Then, the responders rated the targets’ traits and the extent to which they were romantically interested in the target. In essence, we employed Revealed Preference Theory (Samuelson, 1938), in that participants were never directly asked to what they were attracted, but instead we inferred attraction by comparing how the target was rated with how that predicted the responders’ romantic interest.

The data was collected in two rounds. The first round provided 10-minute video observations and corresponding self-report of the male and female targets (Study 1). For the targets, we chose questions and a setting that would allow for differential expression between the targets due to their traits. Then, 24 targets were selected as stimuli representing potential romantic mates. In the second round of data collection, a second set of participants, the responders, were asked to rate the traits of the targets after observing the videos of the targets created during Study 1 and answer whether they were romantically interested in the target (Study 2). Both studies were approved by the Internal Review Board of the hosting university and written consent was obtained from each participant.

We sampled responders and targets from the same university with the target sample collected one year prior to the recruitment of the responder sample. This ensured that the samples were similar, but because of the difference in school years, the responders usually did not know the target persons (this was also asked and those who did had their data omitted from our analyses; less than 1% of the observations). A sample of university students is especially useful for testing this study’s hypotheses because individuals engage in increased sexual activity in their early twenties (Kan, Cheng, Landale, & McHale, 2010), when most students are in college, and with individuals on average not marrying until their mid to late twenties (Copen, Daniels, Vespa, & Mosher, 2012), university students are often engaged in a mate acquisition mindset. A typical university campus is a setting with individuals of a similar age and socioeconomic status (Astin & Oseguera, 2004) concentrated in one environment. We consider the restricted sample a strength of this study because dating is typically reduced to a restricted pool of potential partners, limited by self-selection processes related to socio-economic variables (e.g., Arum, Roksa, & Budig, 2008; Kalmijn & Flap, 2001).

This study includes several methodological improvements over previous studies. First, unlike previous studies that examine only similarity, dissimilarity, or trait levels as predictors of romantic interest, this study evaluated all hypotheses in one sample, testing all hypotheses simultaneously in the same statistical model. Second, the utilization of a half-block design, over a full round-robin design, allowed us to control that the target presented him or herself in the same way to all responders, which is important given research suggesting that how one’s personality is perceived can vary in dyadic settings depending on who the target is talking with (e.g., Kenny et al., 1992, 2007), and allowed us to control for presentation order by randomizing the order in which videos were presented.

Third, we provide three assessments of the targets’ trait levels: 1) the responders’ perception of the target, 2) the consensus view amongst the responders of the target, and 3) the targets’ self-reported trait levels. The consensus score is an application of Kruglanski’s (1989) constructivist approach, one of the three different theoretical approaches to estimating a target’s trait levels identified by Funder (1995), which states that the targets’ trait levels are defined as the collective rating of the target made by the whole sample of responders. It is important to examine both a responders’ individual perception of the target as a predictor of romantic interest, as well as the consensus score and the targets’ self-report, because they examine different processes, specifically who one personally thinks the target is (i.e., the responders’ personal perception of the target), who a set of observers thinks the target is (i.e., the consensus rating by a group of responders), and who the target thinks he or she is (i.e., the target’s self-report).

We chose to use both consensus scores and the targets’ self-report because each score type has its own strengths and limitations, however generally, the two types of scores are correlated with one another (e.g., Stillman & Maner, 2009). A strength of the targets’ self-report rating, over the consensus rating, is it is based on a lifetime of experiences, however it might also be biased by self-enhancement by the target (Sedikides, Gaertner, & Toguchi, 2003). The consensus score, compared with the targets’ self-report, is based on only the limited information provided through the videos; however, it has some measurement advantages over the more traditional self-report from the target. A consensus score controls for biases in the responder’s perception (e.g., hormone cycle [Johnston, Hagel, Franklin, Fink, & Grammer, 2001] or relationship status [Simpson, Gangestad, & Lerma, 1990]), which are removed once placed into the aggregate of the consensus scores. And because the consensus score is based on many ratings, it is considered to be a more stable score and in some cases, superior to other methods (Legree, Heffner, Psotka, Martin, & Medsker, 2003), with some fields, most notably in the assessment of ability emotion intelligence, using the consensus rating as the veridical solution to an item (e.g., MSCEIT; Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2002).

Next, we present our methodology.

Study 1 – Target Participants

Method

Participants

The targets were sampled from 102 undergraduate students recruited from the Introductory Psychology Participant Pool and compensated with class credit for participating. During our selection procedure, we excluded four participants who gave an inappropriate response (i.e., selected the same response option for an entire scale) and three participants with outlying values (i.e., 3 standard deviations from the mean) for at least one scale, resulting in a reduced sample of 95. Of the remaining sample, the majority of the participants were female (56%), Caucasian (80%, 10% Multiracial, 10% Other), the average age was 18.85 years (SD = 1.05), and 51% were involved in a romantic relationship.

Measures

All targets completed several self-report measures assessing numerous personality constructs. The questionnaires relevant to this study are presented below.

Mate Value Inventory

The Mate Value Inventory (Kirsner et al., 2003) is a 17-item measure of one’s personal perception of the qualities that are desirable in a romantic partner. Items are “Ambitious”, “Attractive Body”, “Attractive Face”, “Desires children”, “Emotionally stable”, “Enthusiastic about sex”, “Faithful to partner”, “Financially Secure”, “Generous”, “Good sense of humor”, “Healthy”, “Independent”, “Intelligence”, “Kind and understanding”, “Loyal”, “Responsible”, and “Sociable”. Participants responded using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from −3 extremely low on this characteristic to 0 don’t care/average on this characteristic to 3 extremely high on this characteristic and high scores on this measure indicate high mate value. The scale could be considered a general measure of physical attractiveness (e.g., attractive face), sociosexuality (e.g., faithful to partner), personality (e.g., kind and understanding), as well as access to and willingness to provide resources (e.g., generous) and evokes comparable factor scores and sample-level means between men and women. With values above .70 indicating acceptable reliability, Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was acceptable (Full Sample: α = .78; Selected Targets: α = 0.86).

Physical Attractiveness

Physical attractiveness was assessed with a subset of the Mate Value Inventory items, specifically “Attractive Body”, “Attractive Face”, and “Healthy”. This subscale had acceptable reliability (Full Sample: α = .72; Selected Targets: α = 0.84).

Mate Value-Reduced

This subscale included all of the original Mate Value Inventory items, with the exception of the physical attractiveness items, specifically items regarding sociosexuality (e.g., “Faithful to partner”), personality (e.g., “Kind and understanding”), as well as access to and willingness to provide resources (e.g., “Generous”). This subscale had acceptable reliability (Full Sample: α = .72; Selected Targets: α = 0.84).

NEO Five Factor Inventory

The NEO Five Factor Inventory (Costa & McCrae, 1992) consists of 60 questions, which measure the Big-Five personality factors, with 12 items for each factor. Some example items include “I am not a worrier” (Emotional Stability), “I like to have a lot of people around me” (Extraversion), “I don’t like to waste my time daydreaming” (Openness to Experience), “I try to be courteous to everyone I meet” (Agreeableness), and “I keep my belongings neat and clean” (Conscientiousness). Participants responded using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from −2 strongly disagree to 0 neutral to 2 strongly agree and high scores indicate high levels on that factor. Cronbach’s alphas for each factor were acceptable - Openness to Experience (Full Sample: α = .73; Selected Targets: α = .75), Conscientiousness (Full Sample: α = .85; Selected Targets: α = .85), Agreeableness (Full Sample: α = .77; Selected Targets: α = .78), Emotional Stability (Full Sample: α = .79; Selected Targets: α = .68) – with the exception of Extraversion (Full Sample: α = .62; Selected Targets: α = .64), which was just below standards of acceptability.

Mini-K

The Mini-K is a 20-item short form measure of slow life history strategy (Figueredo, Vásquez, et al., 2006). Two example items include “I can often tell how things will turn out” and “I am closely connected to and involved in my community.” Participants responded using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from −3 disagree strongly to 0 don’t know/not applicable to 3 agree strongly and high scores on this measure indicate a slow life history strategy. The measure shows adequate convergent validity with other measures of life history strategy (Olderbak, Gladden, Wolf, & Figueredo, 2014) and expected criterion validity with self-reported indicators of covitality, personality, the attachment dimensions, sociosexual orientation, mutualistic and antagonistic social strategies, trait emotional intelligence, executive functioning, and evaluative self-assessment (Figueredo et al., 2014). Low scores are positively related with having an internal schemata of economic instability, maternal insensitivity, and general environmental unpredictability as well as a low socioeconomic status, parent divorce, and parental remarriage, however the measure is unrelated to age of puberty or age of first sexual intercourse (Black, 2015). Cronbach’s alpha was acceptable (Full Sample: α = .73; Selected Targets: α = 0.79).

Procedure

In a counterbalanced order, targets either completed questionnaires about themselves, or created a 10-minute video clip in which they responded to a series of questions about themselves. For the videotaping, the target was alone in a room with the series of questions presented on a computer monitor directly in front of them. The participant sat in a chair placed roughly three to four feet in front of the computer monitor with a video camera pointed at them placed directly above that monitor and a white sheet, used as a neutral backdrop, hanging about one to two feet behind the chair. The researcher began the video recording, and a PowerPoint presentation, which, every 45 seconds, presented the target with a question to respond to about themselves, and then the researcher left the room. The questions were designed to be questions one might ask in an initial encounter, at a social gathering, and/or in a dating situation. We chose questions that would allow the participant to reveal personal aspects about themselves, but were not too personal that the questions would seem uncommon or would make the target would feel uncomfortable. The questions, in order of presentation, were: 1) “What do you like to do for fun?”; 2) “How would your friends describe you?”; 3) “What are some things you like about yourself?”; 4) “What are some things others like about you?”; 5) “What types of things are you good at doing?”; 6) “What is your passion in life?”; 7) “Where do you see yourself in the future?”; 8) “What things would make you not date someone?”; 9) “Describe the best relationship you ever had.”; 10) “Some people say ‘Rules are made to be broken.’ What is your attitude about this?”; 11) “When getting into a dating relationship, some people really want a partner who is attractive and energetic, while others place more value on finding someone who is kind and honest. Where do you stand on this and why?” We presented each target with the same list of questions, in the same order. Targets were asked to first read the presented question aloud, and then to respond to the video camera. We told participants to imagine that the videos would be played to a potential romantic partner, and to respond accordingly.

Selection of targets

Twenty-four targets were selected as stimuli for study 2. To ensure that there was sufficient trait-level variance in our final stimuli sample, we created a composite score that was the average of the targets’ self-reported scores for all traits, and then selected participants with the highest and lowest scores (in a few cases, there was a technical problem with the PowerPoint presentation and/or video recording so that the collected video did not have the participant answering all questions, so we selected the next participant on the list). However, as was pointed out during the review process, this method has many flaws; most importantly, it could have led to a restriction of range on many variables, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Hence, we recommend that in future studies, researchers randomly select participants from the full sample and not duplicate the method we employed here.

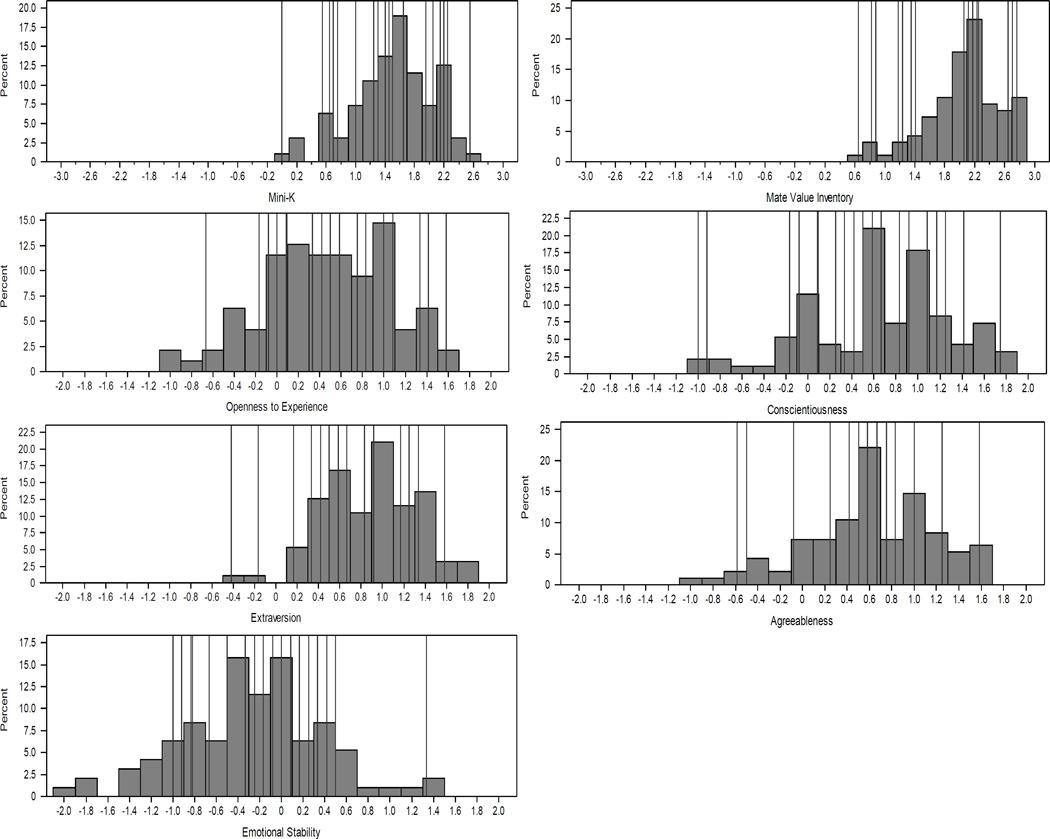

Nevertheless, the method resulted in a final set of selected targets whose mean scores were not significantly different from the full set of targets (see Table 1 and section “Comparability of targets and responders” section), with the trait scores of our selected targets showing a similar range as those of the original sample (see Figure 1), suggesting we had a sufficient sample of the larger target sample. This led to six male and six female stimuli reporting higher scores on the aforementioned traits and six male and six female stimuli reporting lower scores. The final sample was all Caucasian with 11 persons involved in a romantic relationship and the average age was 19.2 years (SD = 1.47). These stimuli targets were divided into six groups, with each group consisting of: 1) one male with higher trait levels, 2) one male with lower trait levels, 3) one female with higher trait levels, and 4) one female with lower trait levels. Then, for each group, we counterbalanced the presentation of each type of target. This procedure resulted in 6 groups of targets and 24 presentation combinations of targets.

Table 1.

Sample-level descriptive statistics of the responders’ and the targets’ self-reported traits

| Trait | Responders (n = 335) | Targets (n = 95) | Selected Targets (n = 24) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X̅ | s | s2 | X̅ | s | s2 | X̅ | s | s2 | |

| Mate Value | 1.97 | 0.52 | 0.27* | 2.06 | 0.49 | 0.24* | 1.99 | 0.66 | 0.42* |

| Physical Attractiveness | 1.49 | 0.99 | 0.97* | 1.78 | 0.77 | 0.59* | 1.65 | 0.92 | 0.85* |

| Mate Value - Reduced | 2.07 | 0.50 | 0.25* | 2.12 | 0.49 | 0.24* | 2.06 | 0.63 | 0.39* |

| Slow Life History Strategy | 1.42 | 0.56 | 0.32* | 1.48 | 0.55 | 0.30* | 1.42 | 0.63 | 0.38* |

| Openness to Experience | 1.45 | 1.01 | 1.02* | 0.45 | 0.59 | 0.35* | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.30* |

| Conscientiousness | 1.26 | 1.07 | 1.15* | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.41* | 0.56 | 0.68 | 0.44* |

| Extraversion | 0.79 | 1.35 | 1.84* | 0.88 | 0.44 | 0.19* | 0.68 | 0.48 | 0.22* |

| Agreeableness | 0.81 | 0.95 | 0.91* | 0.61 | 0.58 | 0.33* | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.27* |

| Emotional Stability | 0.76 | 1.20 | 1.44* | −0.28 | 0.66 | 0.44* | −0.09 | 0.56 | 0.32* |

Note:

p < .05,

X̅ = Mean, s = Standard Deviation, s2 = Variance

Figure 1.

Histograms of questionnaire composite-scores for the original target sample, after excluding participants with inappropriate response patterns and outlier values for at least one questionnaire, with the scores of the 24 selected targets marked with a vertical line.

Study 2 – Responder Participants

Method

Participants

Next, we sampled 368 undergraduate students from the Introductory Psychology Participant Pool who received course credit for participation. Of that sample, 33 participants described themselves as homosexual, bisexual, uncertain, or did not indicate their sex, so these participants were excluded from our analyses, resulting in a final sample of 335 participants who served as our responders. The reduced sample was half male (51%), with the majority of participants Caucasian (72%, 11% Multiracial, 17% Other) and the average age was 18.89 years (SD = 1.21). Less than half of the sample (43%, 70 males and 75 females) was in a romantic relationship while the other half was single.

Measures

The responders completed several self-report questionnaires measuring various personality constructs, including the aforementioned demographics measure, the Mini-K (Male Responders: αMales = .69; Female Responders: αFemales = .73; note because these scores are later estimated separately for each sex, the reliability estimates were also estimated separately for each sex) and the Mate Value Inventory (αMales = .81; αFemales = .75; Physical Attractiveness: αMales = .73; αFemales = .77; Mate Value – Reduced: αMales = .77; αFemales = .68), which met or were just below our standards for acceptability. In addition, the responders completed a personality measure about themselves.

Then, for each target, we asked the responders to complete the Mini-K, the Mate Value Inventory, a personality measure, the Mating Effort Scale (Rowe et al., 1997) in a way that would describe the target, and when responding about a target whose sex they were attracted to, the Romantic Interest Measure, or when responding about a target whose sex they were not attracted to, the Friendship Interest Measure. Because the interest of this paper is on predictors of romantic interest, we do not present results from the Friendship Interest Measure. Also, while the Mating Effort Scale was administered, we decided against analyzing the data because the measure, when revised for the responders to complete in regards to the targets, had a structure that was too confusing for many responders, suggesting the data would be unreliable and inappropriate for interpretation.

To reduce the response burden when completing questionnaires about the targets, the measure of personality was switched from the NEO-FFI (60 items) to the Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI; 10 items; Gosling, Rentfrow, & Swann, 2003) both for the responders’ self-report about themselves and for their description of the target. This was also done by Stillman and Maner (2009) who found that, with the TIPI, responders came to an agreement about the personality factors of the targets roughly to the extent of other studies with longer measures.

Ten-Item Personality Inventory

The TIPI (Gosling et al., 2003) consists of 10 questions that measure the Big-Five personality factors with two questions per factor. Example items include “Extraverted, enthusiastic” (Extraversion), “Critical, quarrelsome” (Agreeableness), “Dependable, self-disciplined” (Conscientiousness), “Anxious, easily upset” (Emotional Stability), and “Open to new experiences, complex.” Participants responded using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from −3 disagree strongly to 0 neutral to 3 agree strongly. We used the Spearman-Browne formula to estimate reliability because it is most appropriate for two-item scales (Eisinga, te Grotenhuis, & Pelzer, 2013). The reliability coefficients for all of the Big-Five personality factors where the responder is rating themselves, while similar to those published by Gosling and colleagues (2003; alphas ranged from .40 to .73), were mostly well below acceptable standards - Openness to Experience (ρMales = .35; ρFemales = .34), Conscientiousness (ρMales = .47; ρFemales = .24), Agreeableness (ρMales = .13; ρFemales = .31), Emotional Stability (ρMales = .47; ρFemales = .58) - with the exception of extraversion (ρMales = .63; ρFemales = .67), which was comparable to our estimates with the NEO-FFI.

Given that estimates of internal consistency can be easily influenced by test length, Clark and Watson (1995) suggested it is also important to consider the interitem correlations, which when within the range of .15 to .50, are seen as evidence for unidimensionality. The five subscales, with two exceptions, fit this criteria, suggesting each subscale measured a single construct: - Openness to Experience (rMales = .21; rFemales = .21), Conscientiousness (rMales = .31; rFemales = .14), Agreeableness (rMales = .07; rFemales = .19), Emotional Stability (rMales = .31; rFemales = .41), Extraversion (rMales = .45; rFemales = .50). Clark and Watson also argued that “goal of scale construction is to maximize validity rather than reliability” (p. 316), which was done by the authors of the TIPI. The TIPI has adequate convergent validity with the Big-Five personality factors, as assessed with the Big-Five Inventory (correlations ranged from .65 to .87), which is often highlighted as support for its psychometric adequacy. Given the scales show evidence for unidimensionality and, in other samples, evidence for convergent validity, we cautiously proceed with their use here. However, it should be noted that a specific concern with the use of this measure is that the reduced scales necessarily have a reduction in the content they can assess and, as a result, there is a higher likelihood of Type II errors, as was highlighted by Credé, Harms, Niehorster, and Gaye-Valentine (2012).

Romantic Interest Measure

This measure consisted of two questions: (1) “How interested would you be in dating this person on a regular basis?, and (2) How much would you like to be romantically involved with this person?” Participants were asked to use a Likert scale, ranging from −3 not interested at all or not at all to 3 extremely interested or a lot for the two questions respectively. Because this measure was completed two times by each responder, estimates of reliability were calculated with Generalizability Theory (GT; Shavelson, Webb, & Rowley, 1989). We applied the estimator restricted maximum likelihood (REML), which prevents against negative variance components, with the predictors in the following order: responder, target, responder*target, item, responder*item, and target*item. To estimate the generalizability of responses across items (i.e., the reliability of this scale), we used the variance attributable to the responder*target interaction as the “true score” effect and the responder*item interaction variance as the “error” variance (i.e., responder*target / [responder*target + responder*item]). The GT coefficient was 1.00 for male responders and .97 for the female responders indicating the scale had good reliability.

The reliability of the responders’ other ratings of the target are discussed below.

Procedure

Responders participated in groups of two to four persons, with each group receiving one of the 24 combinations of targets, and they were not allowed to verbally discuss their responses with each other. During the testing session, participants were first asked to complete the above listed series of questionnaires about themselves. Then, responders were presented with one 10-minute video of a target and, after they watched the entire video, each responder completed the aforementioned measures about the target. We repeated this process for the three additional target videos. Responders were always asked if they knew any of the persons they saw on the video; if so, those data were deleted (less than 1% of the observations). Due to some technical problems, 11% the responders saw only one opposite-sex target while the other 89% saw two opposite-sex targets.

Results

Data Preparation

Comparability of targets and responders

Because all participants were sampled from the same college population, we first tested whether there was sufficient variance within our data to test our hypotheses. The variance for the responders’ and targets’ self-report was significantly different from zero indicating sufficient variance in the scores (see Table 1). A series of between-group t-tests revealed that each target group (n = 4) was not significantly different from the full sample of targets (n = 91, which excluded the four targets in the respective target group), suggesting each group of four targets was a sufficient representation of the target sample. The scale-level means of the responders were not significantly different from the scale-level mean scores of the selected target sample on mate value, physical attractiveness, mate value-reduced, and slow life history strategy. However, the means were significantly different for each of the Big-Five personality factors (with the exception of Extraversion), but this is most likely due to the different measures of personality, and a different range of response options, employed in each sample. When the TIPI composite scores were rescaled to be on the same metric as the NEO-FFI composite scores (NEO-FFI subscale scores were multiplied by 1.5), there was no longer a significant difference between the scale-level means for conscientiousness, extraversion, or agreeableness.

Score computation

Our models included four types of scores: (1) responders’ report on their own traits (denoted as R); (2) responders’ ratings of the targets’ traits (S); (3) the average score among all responders’ ratings of the targets called the consensus score (C = Sn/n where n is the total responder sample size; e.g., Kenny, 1994); and (4) targets’ report on their own traits (T). The consensus score was based on only the ratings from responders rating opposite-sex targets, thus representing an opposite-sex specific view of the target.

Reliability

Since responders offered repeated ratings of the targets, we again used GT to estimate the reliability of the responders’ ratings of the target (S; i.e., the reliability of our scales for this purpose) with the same parameters in the same order as with the Romantic Interest Measure (described under Measures for Study 2). We could not model the dual nested structure so the GT coefficients (ρ2) should be considered an underestimate. For this paper, we set the cutoff for acceptability at ρ2 ≥ .50. Most of the GT coefficients met or were just below our standards for acceptability except for conscientiousness (male responders only), emotional stability (male responders only), and agreeableness (male and female responders; Table 2).

Table 2.

Reliability coefficients, correlations between the consensus rating (C) and the targets’ self-report (T), estimates of perception bias, and proportion of variance in the responders’ ratings of the targets (S) attributable to the target and to the responder

| Generalizability (ρ2) of the responders’ ratings of the target (S) across items |

Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for the Consensus Score (C) |

Correlations between the consensus rating (C) and the targets’ self- report (T) |

Correlation between the responders’ self- report (R) and the responders’ rating of the targets (S) |

Proportion of Variance in the Responders’ Ratings of the Target (S) Attributable to the |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responder | Target | ||||||||||

| Trait | M | F | M | F | M & F | M | F | M | F | M | F |

| Mate Value | .59 | .69 | .20 | .49 | .64* | .22* | .10 | .45* | .18* | .11* | .40* |

| Physical Attractiveness |

.77 | .84 | .38 | .56 | .57* | .03 | .13* | .32* | .21* | .25* | .44* |

| Mate Value – Reduced |

.62 | .71 | .12 | .51 | .60* | .27* | .10 | .45* | .15* | .06 | .43* |

| Slow Life History Strategy |

.47 | .67 | .06 | .57 | .36 | .04 | .08 | .22* | .11* | .04 | .50* |

| Openness to Experience |

.61 | .62 | .10 | .35 | −.13 | .08 | .02 | .19* | .14* | .08 | .30* |

| Conscientiousness | .41 | .71 | .16 | .30 | .36 | .04 | .09 | .27* | .00 | .11* | .30* |

| Extraversion | .54 | .73 | .38 | .42 | .52* | −.01 | −.03 | .04 | .20* | .36* | .33* |

| Agreeableness | .16 | .31 | .01 | .34 | .31 | .36* | .16* | .39* | .11* | .01 | .31* |

| Emotional Stability |

.41 | .62 | .05 | .08 | −.30 | .07 | .03 | .24* | .15* | .03 | .06 |

Note: Values are separated by sex: M indicates the parameters are based on data from male responders rating female targets and F indicates the parameters are based on data from female responders rating male targets. Correlations and variance components that are statistically significant (*p < .05) are presented in boldface.

Next, we used intraclass correlation (ICC), based on the variance components (s2) estimated through social relations modeling (Snijders & Kenny, 1999; described in the next section, Trait Perception), to estimate agreement between responders regarding the traits of the target, thus providing an estimate of the reliability of the consensus scores (; Table 2). Overall, the ICC estimates were very low suggesting relatively low levels of agreement between the responders regarding the targets.

Agreement between the targets’ self-report and the consensus rating

Based on correlations between the targets’ self-report (T) and the consensus scores (C), and applying Cohen’s (1988, 1992) suggestions for effect size interpretation, we see that there is strong agreement between the targets’ ratings of themselves and how they were rated by the responders for mate value, the mate value components, and extraversion, moderate agreement for slow life history strategy, conscientiousness, and agreeableness, and disagreement for openness to experience and emotional stability (Table 2).

Trait perception

Next, we tested whether there was a perception bias in the ratings by the responders of the targets, exhibited as responders rating the targets similarly to themselves, and we examined the proportion of variance in the ratings of the target attributable to the responder and the target, examining possible halo effects.

Perception bias

There was a slight perception bias for some of the traits such that male responders rated targets similar to themselves on mate value, mate value – reduced, and agreeableness and female responders rated the targets similar to themselves on physical attractiveness and agreeableness (see Table 2).

Target and responder variance

With the application of social relations modeling (Snijders & Kenny, 1999) we estimated the proportion of variance attributable to the target and to the responder (Table 2). For female responders, there was a significant proportion of variance attributable to the target for all traits, with the exception of emotional stability, with the proportions .30 or higher (again, except for emotional stability), which is well above the .10 cut-off sometimes used in the literature (e.g., Kenny et al., 1992) indicating there was agreement among women for almost all of the traits as to which men had high and low values. However, for male responders there was a significant proportion of variance attributable to the target only for mate value, physical attractiveness, conscientiousness, and extraversion, which were also above .10 but on average, lower than those for the female responders. Overall, we found that when women rated men, they agreed in their perception more often than when men rated women.

Because the relationship status of the responder could motivate their attention, we also examined effects separated by the relationship status of the responder. For female responders, the traits with a significant proportion of variance attributable to the target did not differ between those who were in a relationship versus those who were not (the pattern matched that of table 2). For male responders who were single, the proportion of variance attributable to the target was significant only for physical attractiveness, conscientiousness, and extraversion, and for male responders who were in a relationship, the proportion of variance attributable to the target was significant only for physical attractiveness. Because there was not much difference regarding which traits male and female responders came to an agreement for based on the relationship status of the responder, we continue to examine these effects combining responders who are and are not in a relationship.

Testing for halo effects

Ratings by the responders may have a halo effect such that the rating of one trait strongly bias the ratings of another (Nisbett & Wilson, 1977). A result is that those traits biased by the halo effect may not be as well perceived as the resulting proportions of variance would suggest. To test for halo effects, we first correlated the responders’ ratings of the targets’ traits for all traits assessed and estimated the shared variance amongst the ratings, identifying trait pairs where the ratings of one trait were strongly related (r > .50) to the ratings of the other trait, with a proportion of shared variance .25 or higher (Table 3)

Table 3.

Correlations between the responders’ ratings of the targets’ traits (S)

| Correlations (r) | Shared Variance (R2) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MV | PA | MVR | SLHS | OE | C | E | A | ES | MV | PA | MVR | SLHS | OE | C | E | A | ES | |

| Mate Value (MV) | .78* | .98* | .58* | .46* | .49* | .22* | .33* | .33* | .60 | .96 | .34 | .21 | .24 | .05 | .11 | .11 | ||

| Physical Attractiveness (PA) | .65* | .63* | .32* | .43* | .31* | .26* | .30* | .27* | .42 | .40 | .10 | .18 | .10 | .07 | .09 | .07 | ||

| Mate Value –Reduced (MVR) | .97* | .44* | .61* | .42* | .50* | .19* | .31* | .32* | .94 | .19 | .38 | .18 | .25 | .04 | .10 | .10 | ||

| Slow Life History Strategy (SLHS) | .72* | .23* | .78* | .17* | .40* | .01 | .14* | .20* | .52 | .05 | .60 | .03 | .16 | .00 | .02 | .04 | ||

| Openness to Experience (OE) | .51* | .23* | .53* | .39* | .30* | .46* | .38* | .31* | .26 | .05 | .28 | .15 | .09 | .21 | .14 | .10 | ||

| Conscientiousness (C) | .56* | .20* | .60* | .66* | .34* | −.02 | .26* | .42* | .32 | .04 | .36 | .43 | .12 | .00 | .07 | .18 | ||

| Extraversion (E) | .42* | .35* | .38* | .18* | .56* | .17* | .21* | .14* | .17 | .12 | .14 | .03 | .31 | .03 | .04 | .02 | ||

| Agreeableness (A) | .54* | .24* | .56* | .55* | .39* | .45* | .18* | .38* | .29 | .06 | .31 | .31 | .15 | .20 | .03 | .15 | ||

| Emotional Stability (ES) | .44* | .28* | .42* | .30* | .25* | .38* | .19* | .41* | .19 | .08 | .18 | .09 | .06 | .15 | .04 | .17 | ||

Note: Estimates specific to female responders are presented below the diagonal and estimates specific to male responders are presented above the diagonal. Correlations that are statistically significant (*p < .05) and shared variance coefficients greater than .25 are presented in boldface.

Overall, the ratings by female responders of male targets had more shared variance than those by male responders of female targets suggesting there was a stronger halo effect amongst female responders than male responders. Interpreting shared variance coefficients above 25%, we found a possible halo effect between mate value and mate value-reduced with slow life history strategy for female and male responders. Specifically amongst female responders, we found that ratings of mate value, mate value-reduced, and slow life history strategy were related to ratings of conscientiousness and agreeableness, ratings of mate value and mate value-reduced were related to ratings of openness to experience, and ratings of extraversion shared variance with ratings of openness to experience. Specifically amongst male responders, there was shared variance between ratings of mate value-reduced with physical attractiveness and conscientiousness.

Because the shared variance mostly involved mate value and slow life history strategy, we interpreted these results to mean that part of the personality ratings by female responders were influenced by their ratings of the targets’ mate value and slow life history strategy, and for male and female responders, ratings of the targets’ mate value and slow life history strategy were related. Life history theory suggests a moderate to strong relation between slow life history strategy, mate value, and personality (e.g., Figueredo, Vásquez, et al., 2006), with personality in these models typically assessed as a general factor of personality (for which there is also evidence of shared variance between personality factors; e.g., van der Linden, te Nijenhuis, & Bakker, 2010), which would suggest that female responders’ ratings are not suffering from a halo effect but instead they represent the true relations between these constructs.

Controlling for halo effects

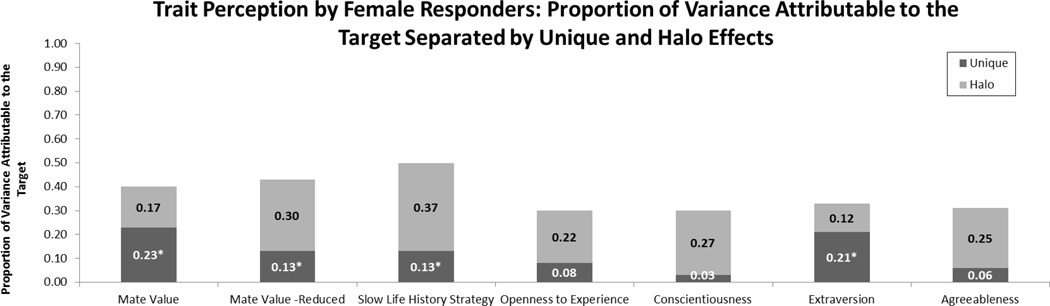

To test the extent to which mate value and slow life history strategy led ratings of the other traits, we re-estimated the proportion of variance attributable to responder and target, after partialling out variance due to the variables with which there was a strong relation (see Table 4). First, we regressed the responders’ ratings of the targets’ traits on the responders’ ratings of the trait that might be leading the ratings (e.g., mate value), and for the residuals, estimated the proportion of variance due to target and responder (as was done above). In all cases, the absolute variance decreased, both for the total amount and for the portion attributable to the target, and the proportion of variance attributable to the target decreased in all instances (with male responders the proportion of .15 was still similar to the previous proportion of .11). The change for male responders was minimal, however for female responders, the drop in proportion of variance attributable to the target was quite large, which we illustrate in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Proportion of variance in responders’ perception of the targets’ traits (S) after controlling for ratings of other traits

| Trait | Trait Partialled Out | Absolute Target Variance (Total Variance) |

Proportion of Target Variance After Partialling |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Partialling | After Partialling | |||

| Female Responders | ||||

| Mate Value | Slow Life History Strategy | .29*(.74) | .08* (.34) | .23* |

| Mate Value – Reduced | Slow Life History Strategy | .33* (.77) | .04* (.30) | .13* |

| Slow Life History Strategy | Mate Value | .49* (.98) | .16* (.46) | .13* |

| Openness to Experience | Mate Value, Slow Life History Strategy, Extraversion |

.48* (1.62) | .07 (1.16) | .08 |

| Conscientiousness | Mate Value, Slow Life History Strategy | .50* (1.67) | .03 (.91) | .03 |

| Extraversion | Openness to Experience | .82* (2.47) | .35* (1.65) | .21* |

| Agreeableness | Mate Value, Slow Life History Strategy | .50* (1.62) | .06 (1.03) | .06 |

| Male Responders | ||||

| Mate Value | Slow Life History Strategy | .06* (.57) | .06* (.38) | .15* |

| Physical Attractiveness | Mate Value – Reduced | .34* (1.34) | .18* (.78) | .23* |

Note: Variance components that are statistically significant (*p < .05) are presented in boldface.

Figure 2.

Proportion of variance in ratings by female responders of male targets that is attributable to the target, both before controlling for halo effects (Unique and Halo combined), and after (identified as Unique), including the proportion specific to halo effect (identified as Halo). Unique portions, that were still statistically significant after controlling for halo effects, are identified with an asterisk (* p < .05).

For both male and female responders, their ratings of the targets’ mate value (as well as the female responders’ ratings of the targets’ mate value-reduced) could not be completely explained by their ratings of the targets’ slow life history strategy. For women, their ratings of the targets’ slow life history strategy could also not be completely explained by their ratings of the targets’ mate value (note: this analysis was not run for male responders because the original proportion of variance in their ratings of female targets’ slow life history strategy attributable to target was never significant). In addition, female responders’ ratings of the targets’ extraversion could not be completely explained by their ratings of the targets’ openness to experience and for male responders, their ratings of the targets’ physical attractiveness could not be completely explained by their ratings of the targets’ mate value-reduced. However, the proportion of variance in female responders’ ratings of male targets’ openness to experience, conscientiousness, and agreeableness specific to the target was no longer significant once controlling for their ratings of the targets’ mate value, slow life history strategy, and extraversion (for openness to experience only) suggesting the latter two to three variables led the ratings of the former three.

In summary, these results suggest that, among female responders, there is evidence of halo effects. Female responders agreed on the male targets’ mate value, mate value-reduced, physical attractiveness, slow life history strategy, and extraversion, but female responders did not agree on the male targets’ openness to experience, conscientiousness, agreeableness, or emotional stability. Among male responders, halo effects were much weak and there was no evidence that the ratings of one trait inappropriately suggested that male responders agreed about another trait. However, given that there was no significant variance attributable to the target for mate value-reduced, but there was for mate value and physical attractiveness, the significant effect for mate value is mostly likely led by the physical attractiveness items, so we conclude that male responders came to an agreement about the female responders’ physical attractiveness and not for the full mate value construct. Thus, our data suggests that male responders came to an agreement about the female responders’ physical attractiveness, conscientiousness, and extraversion, but they did not for mate value, mate value-reduced, slow life history strategy, openness to experience, agreeableness, or emotional stability.

Testing Hypotheses about the Predictors of Attraction

Modeling

Hypotheses 1 to 5 of the predictors of attraction were evaluated simultaneously in a single statistical model, but to keep the models manageable (and because of possible issues with collinearity), they were evaluated separately for each individual difference trait, and separately with the perception, consensus, and target scores (because at least the first two are linearly dependent). We used Multilevel Modeling (MLM) because MLM allows for the partitioning of variance into within- and between-subject effects. Because of the half-block design, observations were dual-nested, nested both within a responder and within a target (Kenny, 2007). The previously presented proportion of variances indicate that a significant proportion of the variance in responses is due to the nested structure, specifically the responder and target, indicating that observations were not independent and that nesting observations within the aforementioned structure was needed. To estimate how similarity, dissimilarity, and high scores predicted romantic interest, we applied polynomial regression with response surface analysis (RSA; see Shanock, Baran, Gentry, Pattison, & Heggestad, 2010, 2014, for a description). We avoided the use of difference scores because of known problems with their reliability (e.g., Peter, Churchill, & Brown, 1993) and decided against tracking accuracy because it does not capture bias (cf. Fletcher & Kerr, 2010). RSA allows one to test the relation between two predictor variables (in our study this is the responders’ self-reported trait levels and one of the three scores representing the targets’ trait levels) as they predict an outcome variable, specifically romantic interest by the responder. The method tests whether agreement or discrepancy between the predictors is related to higher or lower scores on romantic interest, providing the direction of discrepancy as it relates to romantic interest (i.e., responders rating the target as higher than themselves on physical attractiveness predicted more romantic interest), and testing for linear and quadratic relations.

We tested four sets of MLMs that iteratively controlled for possible confounds and allowed us to test the robustness of our effects. In accordance with RSA, the first set of MLMs included the following terms: 1) the responders’ self-reported trait level (R), 2) the responders’ rating of the targets’ traits (S), 3) the quadratic effect of the responders’ self-reported trait levels (R2), 4) the interaction of the responders’ self-reported trait level and the responders’ rating of the targets’ traits (R*S), and 5) the quadratic effect of the responders’ rating of the targets’ trait (S2). These are the five basic terms needed for a RSA analysis and are referred to as the RSA terms throughout this manuscript. In addition, to test hypothesis 4, that sex acts as a moderator, we also included: 6) the responder’s sex as a main effect (X; dummy coded where 0 = female and 1 = male) and an interaction of the RSA terms with the responders’ sex: 7) X*R, 8) X*S, 9) X*R2, 10) X*R*S, 11) X*S2.

Finally, we also controlled for possible confounding variables. Research suggests that individuals who are involved in a long-term romantic relationship rate targets, on average, lower in attractiveness (Simpson et al., 1990), and since attractiveness is related to being perceived as extraverted (e.g., Albright, Kenny, & Malloy, 1988) and responders’ expressing romantic interest (e.g., Buss, 1989), the responders’ relationship status may have an effect on our models. Theoretically, one could also hypothesize that targets’ who were in a relationship at the time they were videotaped acted differently than they would when they are not in a relationship (e.g., less friendly). So we also included the following variables as main effects: 12) the responders’ relationship status (P; dummy coded where 0 = single and 1 = in a relationship), and 13) the targets’ relationship status (G; dummy coded where 0 = single and 1 = in a relationship).

The intercepts were treated as random effects, nested inside the level-2 variables (responders, j, and targets, k) and the predictors were treated as fixed effects. At level 1, the responders’ expressed romantic interest in the target (the outcome variable, Yjk) was expressed as the sum of an intercept for the responder (β0j), an intercept for the target (β0k), a slope for each of the variables presented above, and a random error (rjk):

At level 2, the intercepts for responder and target were expressed as the sum of the overall mean (γ00) and random deviations from that mean (i.e., υ0j or υ0k):

For the consensus models, S was replaced with C, and for the target models, S was replaced with T. All models were estimated in SAS 9.3 with PROC MIXED (TYPE = VC DDFM = SATTERTH; examples of our syntax, along with the data, can be found at https://osf.io/wds5y). To control for multiple significance tests, we employed the Benjamini-Hochberg method (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995) within each MLM, and within each set of surface test estimates (described below) to control for the false discovery rate. This method was chosen over controlling for family-wise error rate because it is considered to have more statistical power (Thissen, Steinberg, & Kuang, 2002). The adjusted p values (padj) were calculated with SAS PROC MULTTEST (Westfall, Tobias, Rom, Wolfinger, & Hochberg, 1999).

An assumption of RSA is that both predictors are on the same numeric scale. This was true for all variables except for the Big-Five personality factors where targets’ self-report scores were assessed with the NEO-FFI, which used 5-point Likert scale, while all other scores were assessed with the TIPI, which used a 7-point Likert scale. Thus, before the MLM analyses, the targets’ self-reported personality scores were adjusted to be on the 7-point Likert scale used by the TIPI by multiplying the targets’ self-reported scores by 1.5. Finally, in accordance with recommendations for the RSA analyses, the R, S, C, and T predictors were kept centered around zero, the midpoint of the scale (Edwards, 1994).

For the first set of models, across all individual difference traits and score types, none of the interactions with sex were statistically significant. Thus, for ease of interpretation, those interactions were removed (per the recommendations of Curran, Bauer, & Willoughby, 2006; this is referred to as a stepwise approach; Muthén, 1994). Our second set of models tested whether the responders’ relationship status moderated any of the effects; here we included an interaction of the RSA terms with the responders’ relationship status. However, across all models there were also no significant interactions. Our third set of models excluded all interactions and included just the RSA coefficients and the main effects of the confounding variables (i.e., responders’ sex, responders’ relationship status, targets’ relationship status). Finally, our fourth set of models included just the RSA coefficients.

When the RSA coefficients were significant, the unstandardized coefficients were entered into four surface test equations (the following are from Shanock and colleagues, 2010, 2014; here, the coefficient numbering of the unstandardized b-weights are directly from the above MLM equation). These were used to create a three-dimensional surface graph that was then interpreted to identify patterns in how the two predictors were related to romantic interest (see Shanock et al., 2010 for an interpretation of the effects a1 to a4). Ultimately, these were the coefficients we interpreted and used to evaluate support for hypotheses 1–5.

Individual perception

First, we examined the extent to which the responders’ self-reported trait levels (R) and the responders’ perception of the target (S) predicted the responders’ romantic interest in the targets. As mentioned above, we found no significant moderating effect of the responders’ sex or of the responders’ relationship status, so the interactions were removed and we estimated just the RSA coefficients, either with or without controlling for the main effects of the confounding variables. See Table 5 for the unstandardized coefficients from the MLMs that did not control for confounding variables. For mate value, mate value – reduced, life history strategy, openness to experience, and extraversion, regardless of whether we did or did not control for the confounding variables, the RSA coefficients were not significant. However, there was a significant effect for the other individual difference traits, which we discuss next.

Table 5.

Responders’ self-reported trait levels (R) and the responders’ ratings of the targets’ traits (S) predicting romantic interest in the target (without controlling for confounding variables)

| Trait | Intercept | R | S | R2 | R*S | S2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mate Value | −.24 | −1.15 | .11 | .12 | .32 | .07 |

| Physical Attractiveness | −1.11* | −.26 | .51* | −.02 | .11* | .04 |

| Mate Value – Reduced | −.06 | 1.35 | .22 | .21 | .26 | .01 |

| Slow Life History Strategy | −.42 | −.90 | .46 | .17 | .26 | −.06 |

| Openness to Experience | −.40 | −.11 | .23 | −.02 | .07 | −.06 |

| Conscientiousness | −.39 | −.32 | .34* | .05 | .08 | −.09 |

| Extraversion | −.43 | −.12 | .01 | .01 | .09 | .01 |

| Agreeableness | −.55* | .07 | .36* | −.003 | −.01 | −.10* |

| Emotional Stability | −.70* | .17 | .34* | −.02 | −.03 | −.05 |

Note: Unstandardized b coefficients are presented. Coefficients that are statistically significant (padj < .05) are presented in boldface.

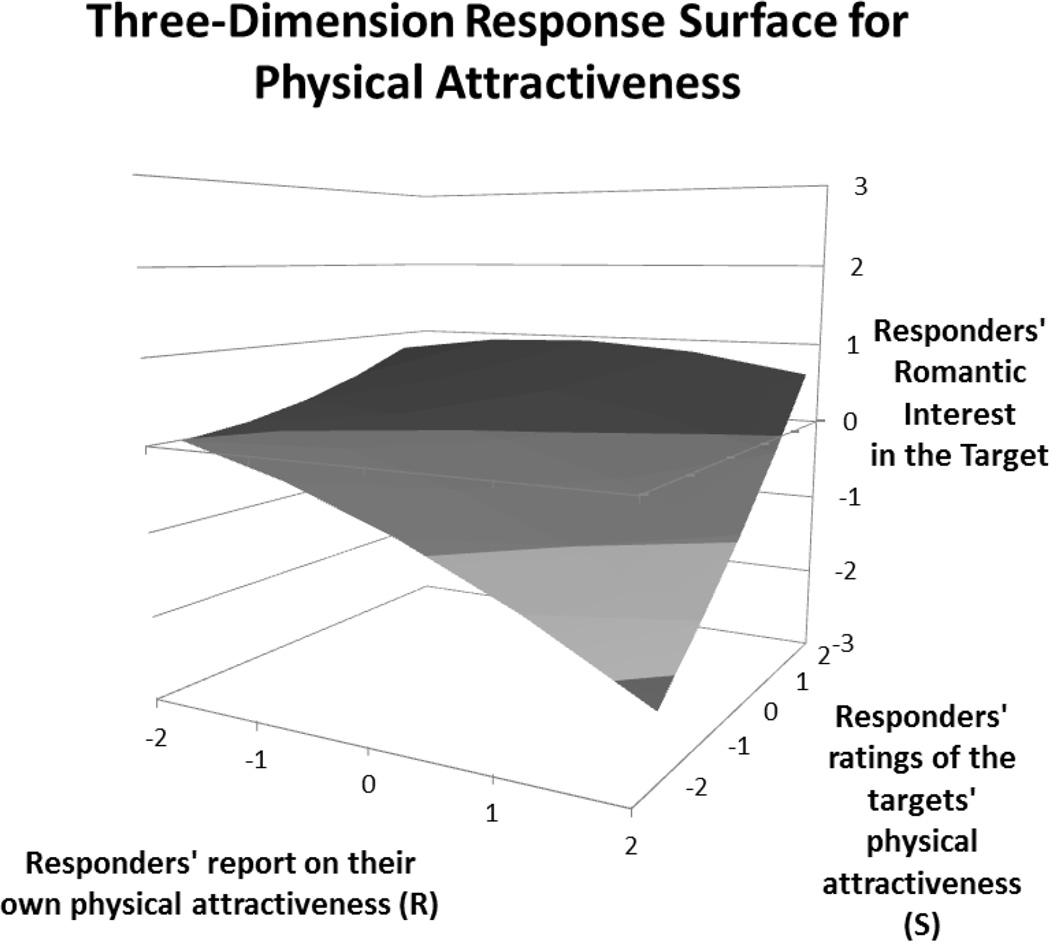

First, the RSA coefficients were significant for physical attractiveness and were robust to controlling for confounding variables. Based on the surface tests (a1 = .25, SE = .18, padj = .22; a2 = .13, SE = .07, padj = .12; a3 = −.77, SE = .15, padj < .0001; a4 = −.10, SE = .08, padj = .22; coefficients are based on the model where the confounding variables were not controlled for), we see that perceiving the target as having higher physical attractiveness than themselves predicted more romantic interest by the responder (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional response surface figure based on the coefficients of the polynomial regression multilevel models with response surface analysis relating the responders’ self-reported physical attractiveness (R) and the responders’ ratings of the targets’ physical attractiveness (S) predicting the responders’ romantic interest in the target.

For conscientiousness, the significance of the RSA coefficients changed depending on whether or not we controlled for the confounding variables, suggesting the significant effects found were not stable. We reran both models, this time including the responders’ perception of the targets’ physical attractiveness (since this was already found this to be a robust predictor of romantic interest) and found that for both models, the RSA coefficients were no longer significant, so the significant effects of the previous model were not interpreted. In these models, the responders’ perception of the targets’ physical attractiveness was still a significant predictor of romantic interest (without controlling for confounding variables, b = .69, padj < .0001).

The RSA coefficients for emotional stability were also significant, and robust to controlling for confounding variables. Because we found that the responders’ perception of the targets’ physical attractiveness was an important predictor in the previous models, we reran both models for emotional stability including this term. In both models, the RSA coefficients for emotional stability were no longer statistically significant, while the responders’ perception of the targets’ physical attractiveness was still a significant predictor of romantic interest (without controlling for confounding variables, b = .71, padj < .0001).

Finally, for agreeableness, the significance of the RSA coefficients changed depending on whether or not we controlled for the confounding variables, suggesting significant effects found were not stable. This pattern did not change when we included the responders’ perception of the targets’ physical attractiveness (without controlling for confounding variables, b = .70, padj < .0001), however the main effect of the responders’ perception of the targets’ agreeableness was no longer a significant predictor, so we proceeded to conducting the surface tests for each version of the model (both with and without confounds with and without controlling for the responders’ perception of the targets’ physical attractiveness). For each of the four models the surface tests were not significant.

In summary, when examining the responders’ perception of the targets’ traits, only physical attractiveness was a significant predictor; responders who perceived the target as having higher physical attractiveness than themselves reported higher romantic interest in that target.

Consensus score

Next, we investigated the extent to which the responders’ self-reported trait levels (R) and the consensus score of the targets’ trait levels (C) were related to romantic interest (Table 6). As mentioned before, there were no significant interactions with the responders’ sex or relationship status, so the interactions were removed and we estimated just the RSA coefficients, either with or without controlling for the main effects of the confounding variables. However, none of the RSA coefficients for any of the traits were statistically significant, which were robust to controlling for the confounding variables. Thus, we found that the consensus ratings were unrelated to the responders’ romantic interest in the target.

Table 6.

Responders’ self-reported trait levels (R) and the consensus score (C) predicting romantic interest in the target (without controlling for confounding variables)

| Trait | Intercept | R | C | R2 | R*C | C2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mate Value | .06 | −2.01 | .18 | .21 | .73 | −.09 |

| Physical Attractiveness | −1.32* | −.15 | .40 | −.04 | .10 | .16 |

| Mate Value – Reduced | −.94 | −1.88 | 1.61 | .27 | .55 | −.52 |

| Slow Life History Strategy | −.55 | −.90 | 1.27 | .19 | .29 | −.61 |

| Openness to Experience | −1.20 | −.11 | 1.07 | −.01 | .05 | −.18 |

| Conscientiousness | −.89 | −.27 | 1.08 | .05 | .04 | −.36 |

| Extraversion | −.73* | −.13 | .20 | .01 | .12 | .10 |

| Agreeableness | −.61 | .18 | .88 | −.03 | −.03 | −.64 |

| Emotional Stability | −.84 | .26 | .46 | −.02 | −.13 | −.08 |

Note: Unstandardized b coefficients are presented. Coefficients that are statistically significant (padj < .05) are presented in boldface.

Targets’ self-report

Finally, we examined the relation between the responders’ self-reported trait levels (R) with the targets’ self-reported trait levels (T) on the responders’ romantic interest in the targets (Table 7). Like with the previous models, there were no significant interactions with the responders’ sex or relationship status, so the interactions were removed and we estimated just the RSA coefficients, either with or without controlling for the main effects of the confounding variables. Of these models, there was only one variable, specifically physical attractiveness, where there was a significant effect amongst the RSA coefficients used to create the surface tests, which was robust to controlling for the confounding variables. The RSA coefficients remained significant, even after controlling for the responders’ ratings of the targets’ physical attractiveness, so we proceeded to conducting the surface tests for each version of the model (both with and without confounds with and without controlling for the responders’ perception of the targets’ physical attractiveness). However, the surface tests for each of the four models were not significant.

Table 7.

Responders’ self-reported trait levels (R) and the targets’ self-report on their own traits (T) predicting romantic interest in the target (without controlling for confounding variables)

| Trait | Intercept | R | T | R2 | R*T | T2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mate Value | 1.32 | −1.78 | −1.00 | .19 | .55 | .18 |

| Physical Attractiveness | −.46 | −.49 | −.01 | −.03 | .25* | .07 |

| Mate Value – Reduced | .87 | −1.86 | −.40 | .27 | .46 | .05 |

| Life History Strategy | −1.34 | −.29 | .94 | .15 | −.11 | −.06 |

| Openness to Experience | −.20 | −.09 | .32 | −.01 | .04 | −.26 |

| Conscientiousness | −.67 | −.26 | .29 | .05 | .03 | .10 |

| Extraversion | −.58 | −.05 | −.62 | .01 | .02 | .53 |

| Agreeableness | −.49 | .12 | .22 | −.03 | .05 | −.14 |

| Emotional Stability | −.55 | .14 | −.43 | −.01 | .08 | −.02 |

Note: Unstandardized b coefficients are presented. Coefficients that are statistically significant (padj < .05) are presented in boldface.

In summary, we found that the target’s self-reported scores were unrelated to the responders’ romantic interest in the target.