Abstract

The present work explores the theoretical relationship between positive spontaneous thoughts and incentive salience – a psychological property thought to energize wanting and approach motivation by rendering cues that are associated with enjoyment more likely to stand out to the individual when subsequently encountered in the environment (Berridge, 2007). We reasoned that positive spontaneous thoughts may at least be concomitants of incentive salience, and as such, they might likewise mediate the effect of liking on wanting. In Study 1, 103 adults recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk reported on key aspects of ten everyday activities. As predicted, positive spontaneous thoughts mediated the relationship between liking an activity in the past and wanting to engage in it in the future. In Study 2, 99 undergraduate students viewed amusing and humorless cartoons and completed a thought-listing task, providing experimental evidence for the causal effect of liking on positive spontaneous thoughts. In Study 3, we tested whether positive spontaneous thoughts play an active role in energizing wanting rather than merely co-occurring with (inferred) incentive salience. In that experiment involving 80 undergraduates, participants who were led to believe that their spontaneous thoughts about a target activity were especially positive planned to devote more time to that activity over the coming week than participants who received no such information about their spontaneous thoughts. Collectively, these findings suggest that positive spontaneous thoughts may play an important role in shaping approach motivation. Broader implications and future directions in the study of positive spontaneous thoughts are discussed.

Keywords: positive spontaneous thoughts, incentive salience, positive emotions, automaticity, motivation

Humans are in many ways not unlike Looney Tunes. Though people’s eyes do not spring out of their faces when they perceive a delicious meal or other highly desirable stimulus, the ways in which they do process cues related to previously enjoyed experiences are comparable in some respects (although bounded by the constraints of facial anatomy). One influential perspective suggests that the construct “reward” is comprised of separable sub-processes (Berridge, 2007). Specifically, liking a given stimulus is distinct from wanting it, and the two are mediated by a third psychological construct called incentive salience. In more concrete terms, experiencing pleasant affect during some activity or behavior (i.e., “liking” the activity) may imbue that concept and closely associated concepts (e.g., physical objects, people) with incentive salience, enhancing the ability of these cues to capture attention in subsequent encounters. That heightened salience in turn generates wanting and motivates approach behavior, increasing the likelihood that the individual will repeat the behavior in question. The primary purpose of the research reported herein is to evaluate positive spontaneous thoughts (i.e., pleasant thoughts that arise without the subjective experience of intent) as a specific psychological mechanism by which incentive salience operates within this theoretical framework. That is, we predict that enjoying an activity will facilitate positive spontaneous thoughts about that activity (i.e., thoughts popping into one’s head instead of eyes popping out of one’s head), and in turn, positive spontaneous thoughts will energize approach behavior.

Incentive Salience

The incentive-salience framework was developed to address questions about the role of dopamine in approach motivation (Berridge, 2007). Whereas prior theories struggled to account for findings that dopamine manipulations seemed to increase appetitive behavior toward a target stimulus with no effect on how well the stimulus was liked, this model separates reward processing into three components: liking, wanting, and learning. In particular, incentive-salience theory unpacks the subprocesses that underlie classical conditioning and suggests that dopamine facilitates only the wanting component of the reward process, which is separately guided by liking and learning (Berridge, 2007; Smith, Berridge, & Aldridge, 2011). That is, when an individual repeatedly encounters a stimulus that is experienced as pleasant (i.e., “liking”), the learned associations between that pleasantness and the cues that are predictive of it endow those cues with incentive salience, making them more likely to capture attention in the future. That heightened salience in turn prompts dopaminergic wanting and reward-seeking behaviors when the individual subsequently encounters the salient cues (see Berridge, 2007 for a discussion of how incentive salience underlies classical conditioning). Findings in animal models have been consistent with this framework (Cagniard, Balsam, Brunner, & Zhuang, 2005; Peciña, Cagniard, Berridge, Aldridge, & Zhuang, 2003; Smith et al., 2011). And in addition, several studies have documented compelling evidence for how incentive salience operates in humans.

First, indexing behavioral effort allowed researchers to disentangle the relationship between liking and wanting in humans (Waugh & Gotlib, 2008). In an initial study, individual differences in the degree to which participants previously enjoyed viewing cartoons were predictive of the effort those individuals were willing to expend to earn the opportunity to view more cartoons when low levels of effort were required. The evidence also showed that the constructs of liking and wanting do not always go hand-in-hand: when participants had to expend more effort to view additional cartoons, the tie between liking and wanting was severed.

Other research has helped to clarify the salience attribute of incentive salience by showing that positively valenced words are perceived in ways suggestive of heightened approach motivation. That is, study participants overestimated the font size of the text in which positive words were presented (relative to neutral words), as well as the duration of time for which they were displayed, implying that positive cues possess a perceptual emphasis (Ode, Winters, & Robinson, 2012).

To clarify how incentive salience seems to energize appetitive behavior, consider the following example. When individuals attend an exercise class, the extent to which they experience positive affect during the class may engender the concept of that class, as well as related people and objects (e.g., their exercise buddy, workout clothes, water bottle, exercise mat) with heightened salience. As such, upon encountering those people and objects in the future, those visual cues will be more likely to capture attention and evoke some urge, however subtle, to attend that class again.

In light of this framework, positive spontaneous thoughts may relate to incentive salience in several ways. First, positive spontaneous thoughts may be indicators of the incentive salience attributed to cues linked with past pleasurable activities. If positive affect endows the mental concept of a stimulus with heightened salience, that concept and cues related to it may be more likely to emerge spontaneously within conscious awareness at any given time. If so, positive spontaneous thoughts may be an epiphenomenon of incentive salience: a mere marker without downstream effects.

A second possibility, however, is that positive spontaneous thoughts are an active ingredient through which incentive salience functions to motivate subsequent reward-seeking behaviors. To the extent that incentive salience promotes positive spontaneous thoughts through heightened mental accessibility, those thoughts may in turn amplify the resulting sense of wanting, or prompt individuals to develop plans for how they will further pursue the object or activity. We favor this second possibility, which is consistent with prior research suggesting that mental accessibility and positive affect interact to motivate goal pursuit (Aarts, Custers, & Marien, 2008; Custers & Aarts, 2005, 2007). The studies reported herein represent a progressive test of these two kinds of relationships, first exploring whether positive spontaneous thoughts mediate the effect of liking on wanting and then evaluating whether they may actively shape wanting and subsequent behavior. The overarching hypothesis of the current research is that positive spontaneous thoughts occupy a key motivational role situated between liking and wanting. Further, we predict that positive spontaneous thoughts don’t simply reflect incentive salience, but rather function as incentive salience by amplifying approach motivation.

Positive Spontaneous Thoughts

At least four distinct lines of research are congruent with the overarching hypothesis that positive spontaneous thoughts may be a key mechanism through which incentive salience generates appetitive behavior. First, recent research on people’s perceptions of their own spontaneous thoughts indicates that such thoughts are felt to be more meaningful than their deliberate counterparts (Morewedge, Giblin, & Norton, 2014). Positive spontaneous thoughts may thus be particularly potent drivers of approach behavior. For instance, it seems plausible that repeatedly noticing the prominence of a given activity (or person, object, etc.) in one’s mind could spur an individual to make specific plans to pursue that activity. In this way, positive spontaneous thoughts may operate as small nudges that collectively facilitate approach behavior. This view is consistent with the logic of self-perception theory, which suggests that people infer their own attitudes and other information about themselves by observing their behavior (Bem, 1967, 1972), and in this extension, their thoughts.

Second, one model of recurrent thought posits that concepts and cues associated with unfulfilled goals are granted extra salience, which results in repeated, unintended thoughts related to the goal (Martin & Tesser, 1996). To bridge this model with the perspective on incentive salience as developed here, one may consider how previously enjoyed activities (or persons) that bear the promise of future repetition (or encounters) may be held in mind as perpetually unfinished business in ways that increase the likelihood that at any given time, thoughts about these activities (or persons) will spontaneously enter conscious awareness. Although recurrent or even intrusive thoughts are more traditionally associated with unpleasant experiences, this perspective highlights one pathway by which pleasant experiences might generate positive spontaneous thoughts and energize approach motivation. For instance, evidence regarding other-praising emotions (e.g., gratitude; Algoe & Haidt, 2009) suggests that among the aftereffects of these positive emotions is an unbidden shift in cognitions about the praised other – such as becoming aware of that person’s positive qualities – that may serve to inspire subsequent interactions and other relationship-promoting behaviors (Algoe, 2012).

Third, research on the basic mental constructs that support goal pursuit is also congruent with the perspective we advance here. Specifically, recent research demonstrates that concepts that possess heightened mental accessibility and are associated with positive affect are wanted more and pursued more vigorously, relative to concepts paired with neutral or negative affect (Aarts et al., 2008; Custers & Aarts, 2005, 2007). Positive spontaneous thoughts by definition entail both mental accessibility and positive valence, and as such, they are well suited to energize wanting and approach behavior. Indeed, one study found that positivity of spontaneous thoughts about physical activity was cross-sectionally related to engagement in physical activity assessed daily over two weeks (Rice & Fredrickson, 2016, Study 2).

Fourth, research on cognitive broadening and narrowing effects is also consistent with our predictions. Although the first two processes described above apply to thoughts of any affective valence, theory and past evidence suggest that pleasant and unpleasant spontaneous thoughts may diverge in at least one key domain. To the extent that positive affect broadens attention (Fredrickson, 1998, 2001, 2013; Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005) and promotes cognitive processing that is flexible and divergent (Estrada, Isen, & Young, 1994; Isen, Daubman, & Nowicki, 1987), relative to negative affect and neutral states, positive affect experienced during an activity may cast a wider net of salience onto co-occurring cues. This conceptualization offers a new lens on the robust findings of “less marked cuing effects for negative than for positive affect” (Isen, 1993, p. 262). Data indicating that positive affect improves people’s ability to detect semantic associations among groups of words provides suggestive evidence (Isen et al., 1987). Though one might expect the avoidance-oriented salience created by negative affect to be especially intense (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, & Vohs, 2001), its cue-driven repellant effect appears to have a narrower foothold.

The Present Research

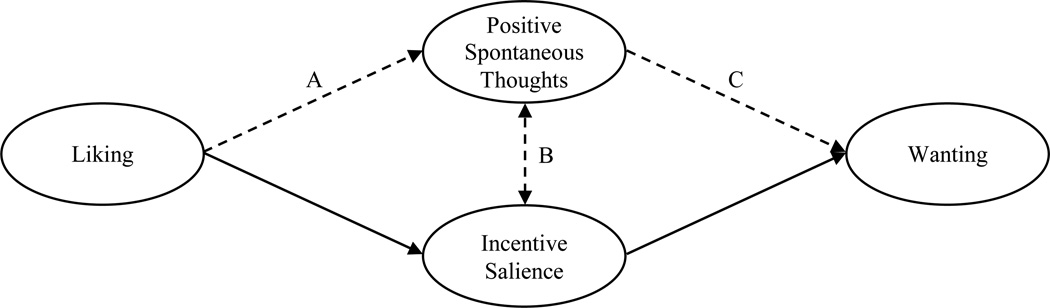

The three studies reported here were designed to investigate positive spontaneous thoughts in a variety of contexts, and to evaluate the larger conceptual model with the added rigor of experimental control; see Figure 1. Specifically, Study 1 uses survey methodology to test the predicted mediation model – from liking to wanting, through positive spontaneous thoughts – across a diverse array of behavioral contexts. Study 2 incorporates an experimental manipulation of liking to test the causal effect of experienced positive affect on subsequent spontaneous thoughts. Finally, Study 3 uses a bogus-feedback paradigm to experimentally manipulate individuals’ perceptions of the positivity of their spontaneous thoughts about a particular activity to test the causal effect of these thoughts on wanting and intentions to engage in that activity. To the extent that incentive salience and positive spontaneous thoughts co-occur as hypothesized, the present studies also afford an opportunity to advance measurement in this area by evaluating positive spontaneous thoughts as indicators of heightened incentive salience (Figure 1, path B). All three studies were approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board and were planned, conducted, and reported according to guidelines for the responsible and transparent conduct of research (Simmons, Nelson, & Simonsohn, 2011).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of central hypotheses

Note: Previously theorized or established paths are depicted in solid lines and key hypothesized paths are in dashed lines. The overarching hypothesis of the studies presented herein is that positive spontaneous thoughts occupy a key motivational role situated between liking and wanting. Further, we predict that positive spontaneous thoughts don’t merely reflect incentive salience, but rather function similarly to incentive salience by amplifying approach motivation. Study 1 tests paths A and C in a correlational design, Study 2 tests path A in an experimental design and path B in a correlational design, and Study 3 tests path C in an experimental design.

Study 1

The primary purpose of Study 1 was to test whether people tend to have more positive spontaneous thoughts about activities they enjoy, and whether those thoughts in turn predict differences in wanting across a variety of contexts. To those ends, we asked participants to rate multiple activities in terms of how much they enjoyed them during the previous week (excluding “yesterday”) and how positive their spontaneous thoughts about those activities had been in the previous 24 hours. Participants also reported how much they wanted to engage in each activity in the coming 24 hours. Further, to rule out alternative explanations, participants reported on how much control they typically felt they had over whether and when to enact the activity (to disentangle obligation from autonomous wanting), when they last engaged in the activity, when they planned to engage in the activity next, and how frequently they typically engaged in the activity. Based on our overarching hypothesis that positive spontaneous thoughts mediate the relationship between liking an activity and subsequently wanting to engage in that activity, we predicted that participants would report more positive spontaneous thoughts about activities that were more well-liked, and in turn, the positivity of spontaneous thoughts would predict wanting, above and beyond obligation and frequency of actual behavior.

Method

Participants

The study sample included 103 adults living in the United States recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk; our aim was to recruit 100 participants based on the results of a power analysis, though 103 actually completed the entire procedure. The sample was fairly balanced in terms of gender (52.4% identified as male; 47.6% identified as female), and participants predominantly identified as White or Caucasian (83.5%), although other ethnicities were represented (1.9% American Indian or Alaska Native, 6.8% Asian, 4.9% Black or African American, 2.9% “other”). Participants ranged in age from 19 to 65, and the mean age was 35.73 (SD = 11.60). Commensurate with MTurk norms, participants were compensated $0.25 for completing the brief online survey.

Procedure

Participants who provided informed consent completed the study by reporting on different aspects of target activities. Ten activities were randomly drawn from a list of common daily activities gathered from multiple sources including the American Time Use Survey and items included in the Day Reconstruction Method (Kahneman, Krueger, Schkade, Schwarz, & Stone, 2004). The final list of target activities included exercising or being physically active, eating a nutritious meal, commuting, learning something new, socializing, running errands, relaxing, doing chores, purchasing consumer goods, and caring for household members.

First, participants read a description of spontaneous thoughts (provided below) and then estimated how many times they noticed having a spontaneous thought about each activity in the past 24 hours. Then, for activities that had been the subject of at least one spontaneous thought, they rated how positive and negative those thoughts were on separate scales that ranged from 0 (“Not at all”) to 10 (“Extremely”). In answering the valence items, participants were asked to consider how positive and negative their thoughts about each activity had been on average in the past 24 hours.

“Take a moment to reflect on the spontaneous thoughts you have about each activity listed below. Sometimes, you might deliberately think about a given activity - maybe cooking, if you are trying to remember a recipe - but other times, you might find yourself thinking about that activity without meaning to - perhaps because excited thoughts about an upcoming meal just keep coming to mind. Here, we are especially interested in that second kind of thought - the kind that you have without trying. Sometimes spontaneous thoughts might seem to just pop into your head, or other times you might catch yourself thinking about something without remembering why you started. Sometimes these thoughts are pleasant, and other times they are unpleasant.”

Next, participants reported on the positive and negative emotions they experienced during each activity in the week before the previous day. Specifically, participants responded to items asking them to estimate the extent to which they experienced positive and negative emotions during the target activities, using separate scales that ranged from 1 (“Not at all”) to 7 (“Extremely”). Participants were also able to select a “Not applicable” option if they had not engaged in a given activity during the specified time period.

In the next section, participants reported how much they wanted to do each activity in the next 24 hours, using a scale that ranged from 1 (“Not at all”) to 7 (“Extremely”). The instructions specifically asked respondents to consider wanting strictly in terms of what they felt, regardless of practical issues, such as scheduling constraints. Again, participants were able to select a “Not applicable” option if they felt the activity did not apply to them.

Last, participants reported in the same manner on several other factors including how much autonomy versus obligation they generally felt in deciding whether and when to engage in each activity, how recently they last engaged in each activity, how soon they planned to engage in each activity next, and how often they generally engaged in each activity. After completing these items, they provided demographic information and were provided with a debriefing statement that explained the purpose of the study and the primary hypotheses.

Analytic Strategy

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3. Given the nested structure of the data (i.e., multiple activities rated by each participant), we used multilevel modeling to test the predicted associations among liking, positive spontaneous thoughts, and wanting. More specifically, we first tested whether liking predicted positivity of spontaneous thoughts, parsing within- and between-person effects by including both the person-mean centered values and the mean-centered person means as predictors. We then tested whether positivity of spontaneous thoughts predicted wanting using an analogous model, while also controlling for obligation and activity frequency. Both models included a random intercept and a random slope for the key predictor variable. To test our prediction that positive spontaneous thoughts mediate the relationship between liking an activity and wanting to engage in it, we analyzed a lower-level (1-1-1) mediation model using the selection-variable approach (Bauer, Preacher, & Gil, 2006) to estimate the entire model simultaneously. In ancillary sensitivity analyses, we tested the specificity of the predicted effects by evaluating analogous processes both in the context of negative affectivity and in terms of spontaneous thought frequency, regardless of valence.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Although participants were allowed to opt out of responding to items that were not applicable (e.g., if they never engaged in a particular activity), missing data accounted for less than 6% of cases on most variables. If participants reported not having any spontaneous thoughts about a given activity in the past 24 hours, they were not asked follow-up questions about thought valence, so these variables have higher rates of missingness (positivity = 14.76%; negativity = 18.35%). See Tables 1 and 2 for more detailed information on missing data and descriptive statistics.

Table 1.

Study 1 Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | N | Min | Max | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST Frequency | 1030 | 0 | 100 | 3.30 | 5.50 |

| ST Positivity | 878 | 0 | 10 | 6.06 | 2.82 |

| ST Negativity | 841 | 0 | 10 | 2.00 | 2.78 |

| Positive Emotions | 970 | 1 | 7 | 4.53 | 1.73 |

| Negative Emotions | 975 | 1 | 7 | 2.99 | 1.82 |

| Wanting | 992 | 1 | 7 | 4.10 | 2.11 |

| Autonomy | 991 | 1 | 7 | 4.41 | 1.98 |

| Last Time | 1030 | 1 | 6 | 4.68 | 1.22 |

| Next Time | 1030 | 1 | 7 | 2.25 | 1.59 |

| How Often | 1030 | 1 | 7 | 5.55 | 1.61 |

Note: Sample sizes differ across variables because in some cases participants were given the option not to report on individual activities if a particular item did not apply. In other cases, as with spontaneous thought frequency, if participants did not have any spontaneous thoughts about a given activity in the specified time period, they would enter “0” rather than “not applicable.”

Table 2.

Study 1 Correlation Matrix

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ST Frequency | - | |||||||||

| 2 | ST Positivity | .12* | - | ||||||||

| 3 | ST Negativity | −.03 | −.50* | - | |||||||

| 4 | Positive Emotion | .17* | .61* | −.35* | - | ||||||

| 5 | Negative Emotion | −.01 | −.25* | .43* | −.18* | - | |||||

| 6 | Wanting | .20* | .57* | −.35* | .67* | −.16* | - | ||||

| 7 | Autonomy | .08* | .40* | −.27* | .52* | −.11* | .57* | - | |||

| 8 | Last Time | .22* | .14* | −.05 | .27* | .02 | .24* | .14* | - | ||

| 9 | Next Time | −.19* | −.13* | .13* | −.24* | .06 | −.26* | −.16* | −.71* | - | |

| 10 | How Often | .21* | .11* | −.02 | .29* | .07* | .27* | .22* | .76* | −.79* | - |

Note: * p < .05

Hypothesis Testing

First, we tested whether positive emotions experienced during an activity, our index of liking, predicted positivity of spontaneous thoughts about that activity by analyzing a multilevel model with a random intercept and random slope; Table 3 presents all parameter estimates for primary analyses in Study 1. As predicted, a significant effect of liking on positivity of spontaneous thoughts emerged both between and within individuals.

Table 3.

Study 1 Primary Analyses

| Outcome | Effects | Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positivity of STs |

Intercept | 5.91 | 0.13 | 45.73 | 101 | <.001 | 5.65, 6.17 |

| Positive Emotion (W) | 1.03 | 0.07 | 14.97 | 766 | <.001 | 0.89, 1.16 | |

| Positive Emotion (B) | 1.02 | 0.15 | 7.04 | 101 | <.001 | 0.73, 1.31 | |

| Wanting | Intercept | 1.64 | 0.26 | 6.32 | 101 | <.001 | 1.13, 2.16 |

| Positivity of STs (W) | 0.35 | 0.03 | 10.80 | 757 | <.001 | 0.29, 0.41 | |

| Positivity of STs (B) | 0.21 | 0.05 | 4.22 | 101 | <.001 | 0.11, 0.32 | |

| Autonomy of Behavior | 0.37 | 0.03 | 12.44 | 747 | <.001 | 0.31, 0.43 | |

| Frequency of Activity | 0.17 | 0.04 | 4.37 | 747 | <.001 | 0.09, 0.25 | |

| Time to Next Activity |

Intercept | 5.59 | 0.17 | 32.54 | 101 | <.001 | 5.25, 5.93 |

| Positivity of STs (W) | −0.04 | 0.01 | −3.39 | 773 | <.001 | −0.07, −0.02 | |

| Positivity of STs (B) | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.65 | 101 | .52 | −0.06, 0.12 | |

| Time Since Last Act. | −0.74 | 0.03 | −22.79 | 773 | <.001 | −0.80, −0.68 | |

Note: All models include random intercepts and random slopes for the within-person effects (W). Between-person effects are denoted (B).

Next, we tested whether positivity of spontaneous thoughts predicted subsequent levels of wanting by testing an analogous model. As predicted, a significant effect of positive spontaneous thoughts on wanting emerged – again, between and within individuals – even when obligation and overall frequency of behavior were included in the model as covariates; the within- and between-person effects of positive spontaneous thoughts on wanting were significant regardless of whether obligation and frequency of behavior were included as covariates. In an additional analysis, positivity of spontaneous thoughts also predicted how soon participants planned to next engage in a given activity, controlling for how recently they had last engaged in the activity, although in this model, only the within-person effect was significant; the pattern of results did not change when the covariate was excluded from the model.

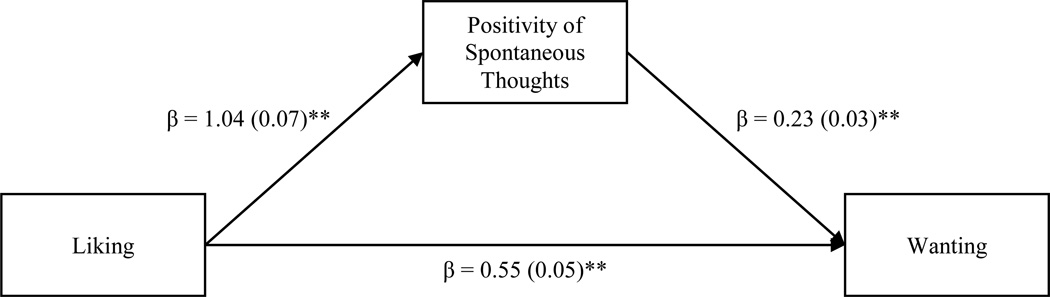

To test our hypothesis that positivity of spontaneous thoughts would mediate the relationship between liking and wanting, we used the selection-variable method for simultaneously estimating the paths of a 1-1-1 multilevel model (Bauer et al., 2006). Because the within- and between-person effects were all significant in the previously reported models, we did not test those effects separately in the mediation model. Consistent with the analyses reported above, the total effects of liking on positivity of spontaneous thoughts and of positivity of spontaneous thoughts on wanting were both significant; see Figure 2. Further, the direct effect of liking on wanting was significant as well (β = 0.55, SE = 0.05, t(85.7) = 10.60, p < .001, 95% CI = [0.45, 0.66]). Subsequent bootstrapping analysis with 10,000 draws revealed that the average indirect effect of liking on wanting through spontaneous thoughts was significant as hypothesized (estimate = 0.26, SE = 0.05, p < .001, 95% CI = [0.17, 0.35]).

Figure 2.

Study 1: Positive spontaneous thoughts mediate the effect of liking on wanting (N = 103)

Note: As hypothesized, the total effect of positive emotions experienced during an activity (“liking”) on positivity of subsequent spontaneous thoughts about that activity was significant; standard errors are included in parentheses. Likewise, the effect of positivity of spontaneous thoughts about an activity on subsequent wanting to do that activity was also significant. Further, the direct effect of liking on wanting was significant as well. Subsequent bootstrapping analysis with 10,000 draws revealed that the average indirect effect of liking on wanting through spontaneous thoughts was also significant as hypothesized. ** p < .001

Ancillary Sensitivity Analyses

Given that the planned analyses were consistent with our hypotheses, we pursued ancillary analyses to determine whether the observed effects were specific to positive spontaneous thoughts or they reflected more general phenomena that applied regardless of valence. As such, we first removed thought positivity from the model and tested whether the mere frequency of spontaneous thoughts about an activity – positive or negative – predicted subsequent levels of wanting to engage in that activity above and beyond the effects of obligation and the frequency with which the activity is typically completed. This analysis revealed a significant within-person effect, such that participants reported greater levels of wanting to do activities about which they had more frequent spontaneous thoughts, regardless of the valence of those thoughts; see Table 4 for parameter estimates. However, the between-person effect was not significant; the pattern of results did not change when covariates were omitted. To further explore processes related to spontaneous-thought frequency, we tested a model in which positive emotions and negative emotions during an activity both predicted spontaneous-thought frequency. Interestingly, the within-person effect of positive (but not negative) emotions was significant, which means that participants had more frequent spontaneous thoughts about activities they enjoyed more intensely. Neither between-person effect was significant.

Table 4.

Study 1 Ancillary Sensitivity Analyses

| Outcome | Parameter | Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wanting | Intercept | 0.66 | 0.26 | 2.57 | 101 | .01 | 0.150, 1.162 |

| Frequency of STs (W) | 0.13 | 0.03 | 5.27 | 875 | <.001 | 0.084, 0.183 | |

| Frequency of STs (B) | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.37 | 101 | .17 | −0.014, 0.074 | |

| Autonomy of Behavior | 0.54 | 0.03 | 19.55 | 875 | <.001 | 0.485, 0.593 | |

| Frequency of Activity | 0.19 | 0.04 | 4.60 | 875 | <.001 | 0.107, 0.266 | |

| Frequency of STs |

Intercept | 3.48 | 0.36 | 9.74 | 100 | <.001 | 2.767, 4.183 |

| Positive Emotion (W) | 0.59 | 0.11 | 5.26 | 861 | <.001 | 0.371, 0.813 | |

| Positive Emotion (B) | 0.50 | 0.36 | 1.42 | 100 | .16 | −0.201, 1.207 | |

| Negative Emotion (W) | 0.17 | 0.12 | 1.50 | 861 | .13 | −0.053, 0.398 | |

| Negative Emotion (B) | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 100 | .45 | −0.303, 0.673 | |

| Wanting | Intercept | 1.03 | 0.27 | 3.76 | 100 | <.001 | 0.487, 1.576 |

| Negativity of STs (W) | −0.29 | 0.04 | −7.64 | 723 | <.001 | −0.358, −0.212 | |

| Negativity of STs (B) | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.31 | 100 | .76 | −0.109, 0.079 | |

| Autonomy of Behavior | 0.46 | 0.03 | 14.98 | 723 | <.001 | 0.396, 0.516 | |

| Frequency of Activity | 0.20 | 0.04 | 4.79 | 723 | <.001 | 0.118, 0.283 | |

| Wanting | Intercept | 1.71 | 0.36 | 6.55 | 99 | <.001 | 1.192, 2.228 |

| Positivity of STs (W) | 0.32 | 0.04 | 8.78 | 717 | <.001 | 0.246, 0.387 | |

| Positivity of STs (B) | 0.22 | 0.05 | 4.15 | 88 | <.001 | 0.116, 0.327 | |

| Negativity of STs (W) | −0.07 | 0.04 | −1.97 | 717 | .05 | −0.138, −0.001 | |

| Negativity of STs (B) | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 99 | .41 | −0.052, 0.127 | |

| Autonomy of Behavior | 0.37 | 0.03 | 12.43 | 717 | <.001 | 0.310, 0.427 | |

| Frequency of Activity | 0.16 | 0.04 | 3.99 | 717 | <.001 | 0.079, 0.232 | |

Note: All models include random intercepts and random slopes for the within-person effects (W). However, the random slope for the within-person effect of negative emotion on frequency of spontaneous thoughts was omitted because the model failed to converge when it was included. Between-person effects are denoted (B).

Next, we tested whether negativity of spontaneous thoughts was related to wanting, controlling for obligation and frequency of behavior. This analysis revealed a significant within-person effect, such that activities that were the topic of more negative spontaneous thoughts were wanted less than other activities reported on by the same participant. The corresponding between-person effect was not significant. To further explore the relationship between valenced spontaneous thoughts about an activity and wanting, we created a new model with positivity of spontaneous thoughts and negativity of spontaneous thoughts as simultaneous predictors and autonomy and frequency of behavior included as additional covariates. This analysis revealed robust effects of positive spontaneous thoughts on wanting both within and between participants. By contrast, only the within-person (and not the between-person) effect of negative spontaneous thoughts on wanting was significant (albeit in the opposing direction). The pattern of results in both analyses was unchanged when autonomy and frequency as behavior were omitted from the model.

Discussion

The results of Study 1 are consistent with the predicted model wherein positive spontaneous thoughts mediate the relationship between liking an activity in the past and subsequently wanting to engage in it. That is, consistent with our hypothesis that liking generates positive spontaneous thoughts about a target, we found that activities that were enjoyed to a greater degree were associated with spontaneous thoughts that were more positive. Likewise, we found that activities that were the topic of more positive spontaneous thoughts were wanted in the coming 24 hours to a greater degree, which is consistent with our hypothesis that positive spontaneous thoughts energize wanting. These effects also emerged as significant at the level of the individual, suggesting systematic variability in liking, positive spontaneous thoughts, and wanting across people. Finally, the overarching indirect effect of liking on wanting through positive spontaneous thoughts was also significant.

Ancillary analyses suggested that while these processes are not entirely specific to positive affect (which would have been a surprising outcome, as negative affect is likely to have some bearing on reducing approach motivation), the overall pattern of results suggests that the relationship between positive spontaneous thoughts and wanting may be stronger than that of their negative counterparts. Interestingly, whereas positive emotions during an activity predicted frequency of subsequent spontaneous thoughts, there was no analogous relationship between negative emotions and spontaneous-thought frequency. This finding is consistent with the prediction that enjoyment, relative to displeasure, may cast a wider net of salience onto related cues.

Altogether, these data are consistent with the overarching hypothesis that positive spontaneous thoughts mediate the relationship between liking and wanting across a wide array of behavioral contexts. Central limitations of Study 1, however, are that the data are primarily retrospective and correlational, thus allowing no inferences about causality. Studies 2 and 3 were designed to overcome these limitations by testing the causal relationships between (a) liking and positive spontaneous thoughts (Study 2) and (b) perceived positive spontaneous thoughts and wanting (Study 3).

Study 2

The central purpose of Study 2 was to use an experimental design to test whether liking an activity (in this case, viewing cartoons) causes increases in the positivity of subsequent spontaneous thoughts about that activity. To these ends, we presented participants with a series of cartoons. After viewing and evaluating each cartoon, we measured, in real-time, the spontaneity of thoughts participants reported in a thought-listing task, and shortly thereafter assessed the valence of the reported thoughts and whether they pertained to the cartoons. In preliminary validation analyses, we compared a derived index of positive spontaneous thoughts to a previously validated measure of incentive salience (i.e., font size estimation; Ode et al., 2012) . Unbeknownst to participants, we manipulated the degree of positive affect they were likely to experience while viewing the cartoons by systematically altering the captions of selected cartoons to be humorless. Following our hypothesis that liking an activity generates positive spontaneous thoughts about that activity (and related cues), we predicted that participants who viewed the funnier set of cartoons would subsequently report spontaneous thoughts about those cartoons that were more positive than participants who viewed the less amusing set of cartoons. For secondary analyses, we also measured how much effort participants were willing to expend to view more cartoons of a similar type. This allowed us to investigate whether the positivity of participants’ spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons in this laboratory setting would predict the degree to which they would expend effort to experience more cartoons, a behavioral index of wanting.

Method

Participants

The study sample included 99 undergraduates enrolled in Introductory Psychology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; our aim was to recruit 100 individuals based on the results of a power analysis and estimates of participant-pool activity, although computer issues resulted in lost data for one participant, reducing the final sample to 99 cases. The sample predominantly identified as female (71.43%; 28.57% identified as male), and the majority of participants identified as White or Caucasian (74.49%), although other ethnicities were represented (i.e., 15.31% Asian, 8.16% Black or African American, 2.04% other). Participants ranged in age from 17 to 24, and the mean age was 18.71 (SD = 1.04). Participants earned partial course credit for completing the lab-based experiment.

Procedure

Participants who provided informed consent were randomly assigned to one of two conditions before beginning the study procedure, which was largely adapted from earlier research (Sherdell, Waugh, & Gotlib, 2012; Waugh & Gotlib, 2008). In the first section of the study, participants completed 10 trials that involved simultaneously viewing one cartoon from each of two decks (arbitrarily labeled “LUM” or “GUP”; labels counterbalanced). Their task was to indicate how much they preferred one cartoon or the other using a response scale that ranged from 1 (“Strongly prefer the left cartoon”) to 7 (“Strongly prefer the right cartoon”). In the “funny” condition, all of the cartoons in one deck were funny, and all of the cartoons in the other deck were not funny; that is, their original humorous captions had been replaced by dry statements that merely described the action portrayed. In the “mixed” condition, the makeup of the humorless deck remained the same, but half of the cartoons in the other deck were altered (by removing the captions or replacing them with dry, descriptive captions) so that they were comparable to those in the humorless deck. To summarize, all participants viewed one deck that was entirely humorless, and the other deck was composed of either only amusing cartoons (“funny” condition) or a mix of amusing and humorless cartoons (“mixed” condition). The dual purpose of this task was to provide variable experiences of liking and an opportunity to learn that one deck (“LUM” or “GUP”) was generally more amusing than the other.

In the next section, participants viewed the same 20 cartoons that had appeared in the preference task, this time, one by one. They were asked to rate how much they enjoyed each one when it first appeared by clicking on a visual analog scale spanning the width of the computer screen; responses were recorded in pixels (possible range: 1–1920). These ratings provided an index of liking and were thus used as a manipulation check to ensure that participants in the funny condition found the cartoons in the targeted deck to be more amusing than participants in the mixed condition. Within the context of the procedure, this task enabled participants to learn that one deck was full of humorless cartoons, whereas the cartoons in the other deck tended to be more amusing, but to varying degrees across the two experimental conditions.

Next, participants completed a thought-listing task that lasted three minutes. In this task, participants were asked to clear their minds and let them wander. They were also asked to write down a keyword or brief phrase that described every distinct thought they had during the allotted time. Immediately after reporting a thought, participants were asked to indicate how spontaneous it felt using a response scale ranging from 1 (“Not at all”) to 5 (“Completely”). The experimenter (who was blind to condition) read a set of instructions that explained how to rate thought spontaneity: “a thought would be not at all spontaneous if you deliberately tried to have it or completely spontaneous if it just seemed to pop into your head.” After rating each thought, participants were instructed to clear their minds again and continue the thought-listing task as before.

After the three minutes elapsed, participants were asked to respond to two follow-up questions about each thought they reported, using the keywords and phrases they provided earlier to facilitate recall. Specifically, they were asked to indicate how positive each thought felt on a scale that ranged from 1 (“Not at all”) to 5 (“Completely”) and to complete a binary measure indicating whether each thought pertained to the cartoons from earlier in the study.

Next, participants completed a click-count task previously used as a behavioral measure of wanting (Sherdell et al., 2012; Waugh & Gotlib, 2008). In each of the 36 trials in this task, participants were given the choice to view a cartoon from the LUM or GUP deck, but each deck was associated with a variable cost, such that they had to click on a moving black square a certain number of times to earn the opportunity to view a cartoon from each deck. The values associated with each deck were determined by an algorithm that adjusted the click costs across trials (both in terms of absolute values for each deck and relative differences between them) to determine two indifference points. One indifference point corresponded to how many times participants were willing to click for the funnier deck when the unfunny deck was anchored at 0 (i.e., no effort). A second indifference point corresponded to the analogous value when the unfunny deck was anchored at 15 clicks (i.e., some effort). For example, when the unfunny deck was anchored at 0, perhaps a participant would consistently opt for the funny deck when it cost 5, 10, or 15 clicks, but when it cost 20 clicks or above, his or her choices would become more random. In this way, the algorithm scored how much extra effort participants were willing to exert to earn a cartoon from the funnier deck over a cartoon from the unfunny deck. In cases in which participants’ responses were too random, the algorithm was not able to determine an indifference point within the 36 trials included in the study.

In the next phase of the study, participants completed a font-size estimation task that has previously been used to measure incentive salience (Ode et al., 2012). In this task, participants completed multiple trials that involved comparing target words to a vertical array of the letter “Z” presented along the far left side of the screen in increasing font sizes. Their task was to quickly estimate the size of the font in which the stimulus word was presented, using the array of letters as a reference. Stimuli included 12 words normed as somewhat positive (e.g., melody) or neutral (e.g., paper) that were drawn from a prior study (Ode et al., 2012) as well as the single target word, “cartoon.”

Last, participants provided demographic information and read a debriefing statement that described the hypotheses and the purpose of the study and emphasized the importance of not discussing the study with classmates.

Analytic Strategy

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3. First, preliminary analyses tested whether the experimental manipulation of liking was successful and how our new measure of positive spontaneous thoughts related to a previously validated measure of incentive salience. To achieve the latter, we created an index of positivity of spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons by excluding thoughts rated below the mid-point of the spontaneity scale (i.e., thoughts that were not perceived to be at least moderately spontaneous) as well as thoughts that were reported to be not relevant to the cartoons. We then computed the average positivity ratings of the remaining thoughts (i.e., those that were experienced as relatively spontaneous and pertained to the cartoons) for each participant and compared those scores to responses on the font-estimation task using simple linear regression. We also compared frequency of spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons (i.e., a ratio of number of spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons to total number of spontaneous thoughts) to responses on the font-estimation task in the same way. To evaluate our primary hypothesis, we used simple linear regression to test whether participants randomly assigned to the funny condition experienced spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons that were more positive than those reported by participants in the mixed condition. Finally, in a secondary analysis, we used a similar approach to test whether positivity of spontaneous thoughts predicted indifference points in the click-count task – the behavioral index of wanting.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

See Table 5 for descriptive statistics for key variables.

Table 5.

Study 2 Descriptive Statistics by Condition

| Funny Condition (n = 50) |

Mixed Condition (n = 49) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD |

| Cartoon Ratings | 50 | 1318.59 | 198.20 | 49 | 1163.42 | 157.63 |

| ST Raw Counts | 50 | 8.68 | 5.56 | 47 | 8.55 | 4.37 |

| ST Frequency | 50 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 46 | 0.24 | 0.25 |

| ST Positivity | 36 | 3.64 | 0.84 | 31 | 2.71 | 1.14 |

| Indifference (0) | 38 | 14.87 | 13.18 | 41 | 9.63 | 12.37 |

| Indifference (15) | 40 | 28.00 | 12.34 | 42 | 21.43 | 8.92 |

| Font Estimate | 50 | 0.92 | 1.29 | 49 | 0.76 | 1.33 |

Note: Cartoon ratings were measured in pixels based on a visual analog scale spanning the width of the computer screen was used to record responses; possible values ranged from 1 to 1920. ST Raw Counts corresponds to the number of spontaneous thoughts participants reported, regardless of whether they pertained to the cartoons. ST Frequency corresponds to ratios of number of spontaneous thoughts about cartoons relative to total number of spontaneous thoughts reported during the thought-listing task; ST Positivity refers to the mean positivity scores of spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons; this score could not be calculated for participants who reported no spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons. Indifference (0) and Indifference (15) refer to the indifference points when the unfunny deck was anchored at the value in parentheses. Font Estimate is computed as the difference between participants’ estimates of the size of the font in which the word “cartoon” was displayed and the actual size of the font, so a score of zero would indicate perfect accuracy, and positive values indicate a tendency to overestimate the size of the word cartoon.

Preliminary Analyses

To determine whether participants in the funny condition liked the cartoons in the amusing deck more than participants in the mixed condition liked their analogous cartoons, we aggregated the individual liking ratings (in pixels) for those cartoons into an average liking score for each participant. We then submitted these scores to a simple linear regression analysis in which experimental condition was a dummy-coded predictor variable. Results revealed a significant difference in liking across conditions (β = 155.16, SE = 36.04, t(1) = 4.31, p < .001, 95% CI = [83.64, 226.69]). As expected, participants in the funny condition reported greater liking for the cartoons in the amusing deck than participants in the mixed condition.

Next, we sought to determine whether positive spontaneous thoughts about cartoons corresponded to a previously validated measure of incentive salience. Before testing the predicted association, we analyzed participants’ estimates of positive and neutral words, to determine whether the effect found in previous research (Ode et al., 2012) replicated in the current sample. A paired-sample t-test revealed that participants estimated the text in which positively valenced words were displayed (M = 4.59, SD = 3.82) to be larger than the text in which neutral words were presented (M = 3.46, SD = 3.19), t(105) = 3.63, p < .001, 95% CI = [0.51, 1.74]. Given that the task appeared to have operated as intended, we regressed participants’ font-size estimates for the single word “cartoon” on the average positivity of the spontaneous thoughts they reported about the cartoons. As predicted, the two were positively related, although not at the level of α = .05 (β = 0.30, SE = 0.14, t = 1.98, p = .052, 95% CI = [−0.002, 0.598]). It is worth noting that when all thoughts about the cartoons (regardless of spontaneity) were included, thought positivity was not significantly related to font-size estimates (β = 0.20, SE = 0.15, t = 1.36, p = .18, 95% CI = [−0.09, 0.49]). In addition, frequency of spontaneous thoughts (regardless of valence) was not significantly related to size estimates (β = −0.05, SE = 0.53, t = −0.09, p = .93, 95% CI = [−1.10, 1.00]). Finally, font-size estimates did not differ by experimental condition (β = 0.17, SE = 0.26 t = 0.63, p = .53, 95% CI = [−0.36, 0.69]).

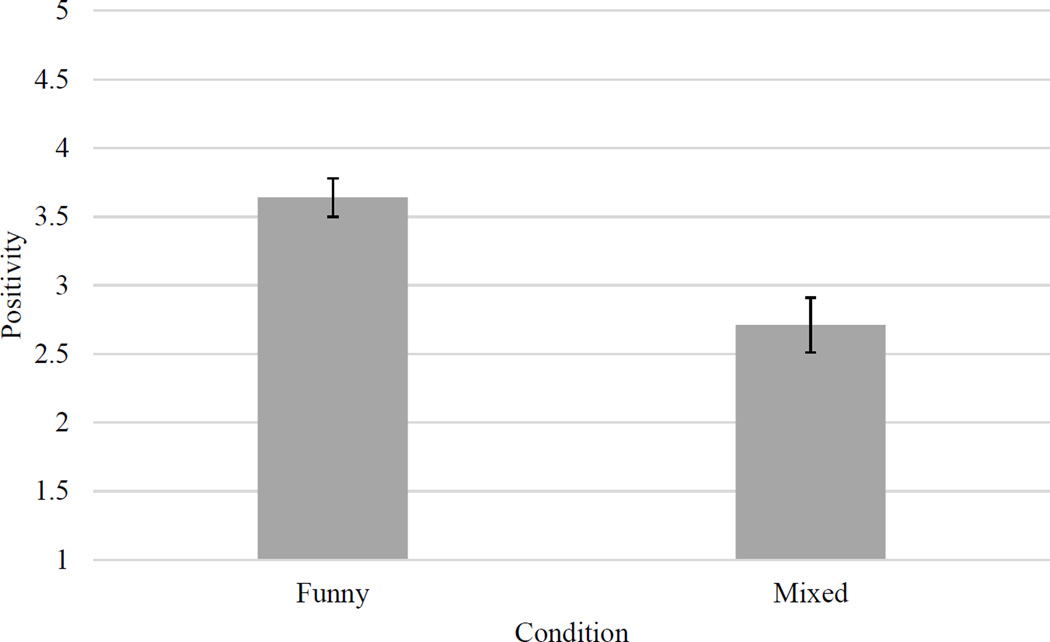

Hypothesis Testing

To test whether the manipulation altered the positivity of participants’ spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons, we submitted those scores to a simple linear regression analysis with experimental condition used to predict positivity of spontaneous thoughts. Consistent with our hypothesis, results revealed a significant effect of condition (β = 0.93, SE = 0.24, t = 3.83, p < .001, 95% CI = [0.45, 1.42]), such that participants in the funny condition reported spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons that were more positive than those reported by participants in the mixed condition (see Figure 3). This pattern suggests that liking an experience generates positive spontaneous thoughts about that experience.

Figure 3.

Study 2: Participants randomly assigned to the funny condition reported spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons that were more positive than those reported by participants in the mixed condition

Note: Consistent with our hypothesis, a simple linear regression analysis revealed a significant effect of condition on positivity of spontaneous thoughts, such that participants who viewed the set of amusing cartoons (n = 50) reported spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons that were more positive than those reported by participants who viewed the mixed set of amusing and bland cartoons (n = 49). This pattern suggests that liking an experience generates positive spontaneous thoughts about that experience. Error bars denote ± 1 standard error.

Ancillary Sensitivity Analysis

In an ancillary sensitivity analysis, we tested whether the experimental manipulation also altered the frequency of participants’ spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons (regardless of valence) to examine the specificity of the effect to positive spontaneous thoughts. Specifically, we submitted thought-frequency scores (i.e., ratios of number of spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons to total number of spontaneous thoughts reported) to a simple linear regression analysis with experimental condition as a binary predictor. This analysis revealed that there was no effect of condition on frequency of spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons (β = 0.03, SE = 0.05, t = 0.58, p = .57, 95% CI = [−0.07, 0.13]). This result supports the conclusion that liking an experience produces positive spontaneous thoughts in particular.

Secondary Analyses

To determine whether the click-cost task operated as expected, we tested whether indifference points differed as a function of experimental condition. Consistent with prior research (Waugh & Gotlib, 2008), participants in the funny condition were willing to work harder than participants in the mixed condition when the unfunny deck was anchored at 15 (β = 6.57, SE = 2.37, t = 2.77, p = .01, 95% CI = [1.86, 11.28]). The analogous effect when the unfunny deck was anchored at 0 merely approached significance (β = 5.23, SE = 2.87, t = 1.82, p = .07, 95% CI = [−0.49, 10.96]). However, the means were in the predicted direction: participants in the funny condition exerted more effort than participants in the mixed condition.

We next explored whether the positivity of participants’ spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons predicted their behavior in the click-cost task. To that end, we first submitted the indifference points when the unfunny deck was anchored at 0 clicks to a simple linear regression analysis with positivity of spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons as the predictor variable. The results of this analysis suggested that there was no association between the positivity of participants’ spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons and the subsequent effort they exerted to view additional funny cartoons (β = −0.05, SE = 1.49 t = −0.03, p = .98, 95% CI = [−3.02, 2.93]). We conducted a similar analysis using the indifference points when the unfunny deck was anchored at 15 clicks, and this model also yielded null results (β = 1.07, SE = 1.13, t = 0.94, p = .35, 95% CI = [−1.20, 3.33]). Frequency of spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons was also unrelated to effort when the unfunny deck was anchored at 0 clicks (β = −4.72, SE = 5.78 t = −0.82, p = .42, 95% CI = [−16.24, 6.81]) and 15 clicks (β = −2.23, SE = 4.92 t = −0.45, p = .65, 95% CI = [−12.03, 7.57]).

Discussion

Study 2 extended the findings of Study 1 by testing the causal link between liking and positive spontaneous thoughts in an experimental context. Consistent with our hypothesis that liking an experience generates subsequent positive spontaneous thoughts about it, participants randomly assigned to the funny condition reported spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons that were more positive than the analogous thoughts reported by participants in the mixed condition. This result enables greater confidence in the hypothesized causal relationship between liking and positive spontaneous thoughts. Further, it is notable that this result is based on thought data reported in real time as opposed to global estimates made retrospectively. Suggesting specificity to positive spontaneous thoughts, no such effect of experimental condition emerged for frequency of spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons.

Study 2 also provided an opportunity to compare patterns of positive spontaneous thoughts to a previously validated indicator of incentive salience based on estimating the font size of a target word. Consistent with our guiding assumption that positive spontaneous thoughts at minimum reflect incentive salience, average positivity of spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons showed an association (albeit at p = .052) with font-size estimation in the predicted direction. That is, participants who had more positive spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons they had viewed tended to perceive the word “cartoon” as being displayed in larger text. We note that the index of font-size estimation used here was based on a single trial (i.e., the word “cartoon”) and thus may not be as reliable as aggregate scores that have been used in prior research (i.e., Ode et al., 2012).

Finally, we explored whether positivity of spontaneous thoughts predicted participants’ willingness to work to view subsequent cartoons (i.e., higher indifference points in the click-count task). Results were null and as such cannot rule out the possibility that positive spontaneous thoughts are epiphenomenal to incentive salience, rather than active ingredients that energize wanting. Even so, alternative explanations for this null result are plausible. Perhaps, for example, the click-count task did not operate in this sample as expected. This interpretation is undermined, however, by the finding that participants in the funny condition were generally willing to work more to view the cartoons – which they reported enjoying more – relative to participants in the mixed condition. Another alternative explanation may be that the effect of positive spontaneous thoughts on subsequently wanting a particular stimulus depends on individuals perceiving that these thoughts are notably positive. In the present study, however, spontaneous thoughts about the cartoons comprised only a minority of people’s spontaneous thoughts (approximately one quarter of spontaneous thoughts in both conditions, see Table 5), and their valence on average, was near the midpoint of the positivity scale. The perception of one’s spontaneous thoughts as notably positive is perhaps a necessary feature for mobilizing approach behavior. To address this possibility, Study 3 deploys an experimental manipulation of the perception of spontaneous thoughts to test whether perceiving such thoughts as especially positive produces greater wanting.

Study 3

The previous studies demonstrate that positive spontaneous thoughts share properties with incentive salience, an inferred construct that yokes liking to subsequent wanting, two neurally-distinct components of reward processing. However, the extent of the similarity remains unclear. Are positive spontaneous thoughts simply indicators or read-outs of incentive salience, or do they also play an active role in energizing wanting?

The present study was designed to test whether the perception of one’s own spontaneous thoughts as especially positive is sufficient to cause increases in wanting. One reason that positive spontaneous thoughts may be potent triggers for appetitive behavior is that people seem to infer more meaning from spontaneous thoughts than from their more deliberate or controlled counterparts (Morewedge et al., 2014). If people perceive their spontaneous thoughts as indicators that they should do something, it may be the case that providing people with feedback to suggest that their spontaneous thoughts about a given activity are especially positive may be sufficient to make them want to engage in that activity.

To test the effect of perceived positivity of spontaneous thoughts on wanting, this experiment adopted a framework inspired by prior research on post-decision spreading of alternatives (e.g., Brehm, 1956). The classic paradigm in that research involves asking participants to rank a series of items (such as household products) in order of desirability and then to choose between two of the items (often the two rated as fifth or sixth most desirable) to receive as a gift. Later, participants are asked to re-rank the items, and the two sets of rankings are analyzed. Typically, the chosen item rises in the rankings, whereas the rejected item falls as the result of a subtle mental calculus that justifies the prior decision.

In the present study, participants rated a series of activities in terms of how much they wanted to do them, then engaged in thought-listing tasks. We implemented a bogus pipeline procedure (Jones & Sigall, 1971) by recording facial EMG and cardio-respiratory responses during the thought-listing tasks. Psychophysiological data were collected to test distinct hypotheses and will be reported elsewhere. For the purposes of the present study the psychophysiological recordings simply served to bolster the credibility of the bogus thought profile presented to participants in one experimental condition. In this “feedback” condition, the computer delivered a prefabricated message suggesting that patterns of subtle facial and physiological activity during the thought tasks indicated that the participant likely experienced spontaneous thoughts about one of the activities that were especially positive. Participants in the control condition received no such message. Next, participants rated the activities once again. To the extent that perceptions of positive spontaneous thoughts motivate wanting, we predicted that participants who received the bogus feedback would report wanting to engage in the target activity more than they had previously, whereas there would be no changes for participants in the control condition. Further, we predicted that participants who received the feedback would intend to engage in the target activity more over the following week than participants in the control condition. Participants’ suspicion was assessed via funneled debriefing (Bargh & Chartrand, 2000) as a possible criterion for exclusion.

Method

Participants

Our a priori aim was to test 80 participants based on the results of a power analysis and estimates of participant-pool activity; accordingly, we recruited 80 undergraduate students enrolled in Introductory Psychology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The average age of participants was 19.18 (SD = 2.54), and the majority of participants identified as female (72.50%; 26.50% identified as male). Although most participants identified as White or Caucasian (64.56%), other ethnicities were represented in the sample (12.66% Asian, 16.46% Black or African American, 6.33% “other”). Participants earned partial course credit by completing the lab-based experiment.

Procedure

Participants enrolled in the study via the psychology participant pool website and were contacted by email 12–24 hours before the beginning of their lab session. The message included a reminder about the scheduled session and asked the participant to complete a brief pre-lab questionnaire. After providing electronic consent, participants rated how much they wanted to do 10 distinct physical activities in the next 24 hours, using a response scale from 0 (“Not at all”) to 10 (“Extremely”). The instructions specifically asked participants to consider their responses strictly in terms of how much they wanted to do each activity, regardless of practical constraints like other obligations, the weather, or the availability of necessary equipment. The 10 activities included running, hiking, walking, swimming, dancing, playing basketball, cycling, playing soccer, doing yoga, and lifting weights. These activities were pre-tested to ensure that they are the kinds of activities undergraduate students on this campus actually do.

Shortly before the beginning of each lab session, the experimenter accessed the prospective participants’ wanting ratings and determined which activity was given the fourth-highest rating. This selection process was also pre-tested to ensure that the target activity would not be consistently given ratings at the very top of the 0–10 wanting scale (in an attempt to avoid a ceiling effect) but would still be something the participant wanted to do at least a little. The experimenter then prepared the electronic questionnaire to be administered during the lab session by specifying which of the ten physical activities would be the target activity for that participant.1

When participants arrived for the scheduled lab session, they were provided with a paper copy of the same consent form and asked to review it before beginning. If participants had not completed the pre-lab questionnaire, they completed the pre-test wanting ratings at the beginning of the lab session, and the experimenter surreptitiously used those ratings to determine which activity would be the target activity and prepared the electronic questionnaire accordingly. Then, the experimenter explained to the participant how she would affix the physiological sensors (i.e., two ECG sensors on opposite sides of the lower torso, a ground sensor on the back of the left hand, a respiration band around the upper torso, a finger-pulse sensor on the middle finger of the left hand, two sensors placed above the left eyebrow to measure activity of the corrugator supercili, two sensors placed below the outer corner of the left eye to measure activity of the orbicularis oculi, and two sensors placed in the middle of the left cheek to measure activity of the zygomaticus major). Once all the sensors were in place, they were connected to the recording equipment (James Long Company, Caroga Lake, NY), and the experimenter visually examined sensor output using Snap-Master data acquisition software (HEM Data Corporation, Southfield, MI) to ensure that the signals were calibrated and recording properly.

Next, participants began the computerized portion of the experiment, during which their only interaction with the experimenter involved listening to scripted instructions. In the first step, they completed a three-minute task that involved viewing neutral pictures of plants to allow for baseline physiology recording. Then, they completed a one-minute task that involved vividly imagining doing the target activity (i.e., the activity that had been given the fourth highest rating on the pre-test wanting questionnaire).

Next, participants completed a three-minute thought-listing task as in Study 2. After the thought-listing phase was completed, participants were asked follow-up questions about each of the thoughts they reported when prompted with the keywords they provided. Specifically, participants were asked to rate how positive and negative each thought felt, using a 7-point response scale that ranged from “Not at all” to “Extremely.” They also indicated whether each thought pertained to the target activity they imagined doing earlier in the study.

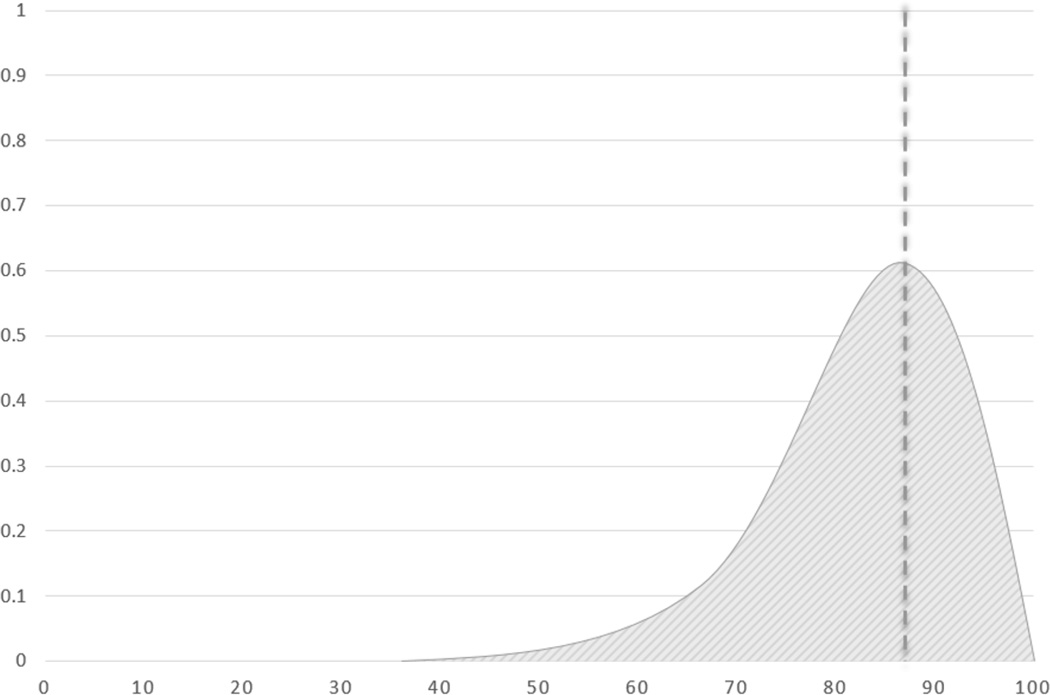

Next, participants who had been randomly assigned to the feedback condition viewed a “thought profile” (see Appendix A) that included the false feedback. The message explained that the participant’s physiological responses and thought data collectively suggested that their spontaneous thoughts about the target activity were likely to be especially positive and was accompanied by a simple graph designed to support the text. The message was pilot tested in a small sample of undergraduates before data collection commenced to ensure that most participants would understand and believe the information. Participants assigned to the no-feedback condition moved to the next section without receiving any feedback.

In the next section, all participants completed a second thought-listing task (this one only one-minute long) and then rated the second set of thoughts they reported; this served primarily as a filler task to temporally separate the manipulation and the dependent measures. Then, they once again rated how much they wanted to engage in each of the ten activities in the next 24 hours. They also reported their plans to engage in each by indicating whether they intended to engage in each activity in the morning, afternoon, or evening of each of the following seven days. Then they used those planned schedules to estimate how many total hours they would devote to each activity in the coming week. Finally, all participants completed two scales (i.e., the Passion Scale Vallerand et al., 2003 and the short form of the Mental Health Continuum scale, Keyes 2002) for exploratory analyses unrelated to the hypotheses of the present study.

After participants completed the computerized tasks, the experimenter removed all physiological sensors and measured the participants’ height and weight to be used as a covariate in analyses of psychophysiological data. Then, the experimenter asked the participant several questions as part of a funneled debriefing procedure designed to detect suspicion of the false feedback or whether the participant had guessed the study hypotheses (Bargh & Chartrand, 2000). Finally, the experimenter read a debriefing statement to the participant that explained the purpose and hypotheses of the study and emphasized the importance of not discussing the study with classmates.

Analytic Strategy

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3. To test the hypothesis that the bogus feedback altered wanting to pursue the target activity, we submitted the wanting scores for the target activities to a repeated-measures ANOVA with condition (feedback, no feedback) as a between-subjects factor and rating (pre-test, post-test) as a within-subjects factor. To test the hypothesis that perceptions of positive spontaneous thoughts amplified wanting, we analyzed the data on participants’ behavioral intentions. We did so by submitting the total number of times each participant intended to engage in the target activity over the following week and the anticipated total duration of those planned instances to separate simple linear regression analyses with condition as a dummy-coded predictor variable.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

See Table 6 for descriptive statistics pertaining to key variables.

Table 6.

Study 3 Descriptive Statistics by Condition

| Control (n = 40) |

Feedback (n = 40) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD |

| Wanting (pre-test) | 39 | 5.46 | 2.11 | 39 | 5.33 | 2.20 |

| Wanting (post-test) | 40 | 4.70 | 2.81 | 40 | 4.58 | 3.00 |

| Thought Frequency | 39 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 40 | 0.24 | 0.26 |

| Thought Positivity | 18 | 4.75 | 1.75 | 25 | 5.01 | 1.74 |

| Intended Episodes | 40 | 3.30 | 5.61 | 40 | 4.03 | 5.74 |

| Intended Hours | 39 | 1.58 | 2.22 | 40 | 2.35 | 2.71 |

Note: Responses on the wanting measure ranged from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating greater wanting. Thought Frequency and Thought Positivity were not included in analyses, but are presented here for context. Thought Frequency refers to the proportion of spontaneous thoughts participants reported during the first thought-listing task that pertained to the target activity. Thought Positivity refers to the average positivity of those spontaneous thoughts that were about the target activity. As is evident in the reduced sample sizes for the Thought Positivity measure, many participants reported no spontaneous thoughts about the target activity during the first thought-listing task.

Suspicion Check

None of the participants in the feedback condition suspected that the message was prefabricated, although five indicated general suspicion in the most stringent interpretation of the results from the funneled debriefing procedure. Excluding those participants from the analyses does not substantially alter the pattern of results2. All analyses below are based on the full sample.

Hypothesis Testing

To test whether participants’ wanting ratings were influenced by their perceptions of positive spontaneous thoughts, we submitted pre- and post-test wanting ratings to a repeated-measures ANOVA with experimental condition as a between-participants factor. The predicted interaction of time and condition was not significant, F(1, 76) = 0.03, p = .86, nor was the main effect of condition, F(1, 76) = 0.13, p = .72. The main effect of time approached significance, F(1, 76) = 3.30, p = .07, with the pattern of means suggesting that participants wanted to do the target activity less at post-test measure than at pre-test.

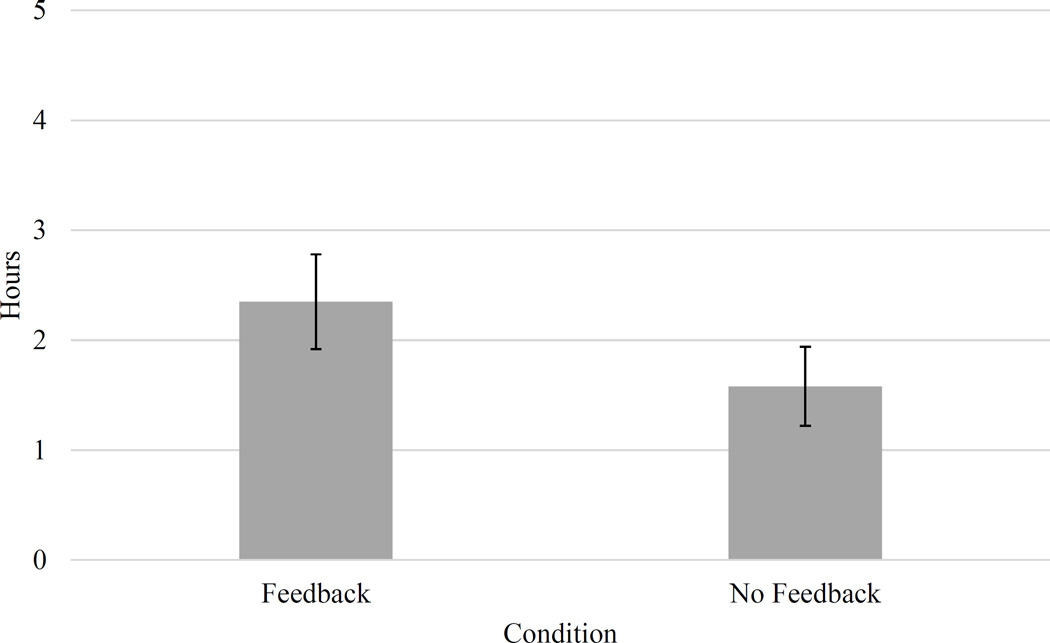

To test whether perceptions of positive spontaneous thoughts altered participants’ intentions to engage in the target activity, we first created a variable corresponding to the number of times participants intended to engage in the target activity in the following week based on the schedules they completed. Then, we submitted those scores to a simple linear regression analysis following a Poisson distribution (given the count nature of the outcome variable) with experimental condition as a dummy-coded predictor variable. This analysis revealed a marginally significant effect of condition on number of behavioral intentions (β = 0.20, SE = 0.12, p = .09, 95% CI = [−0.03, 0.43]). As a second index of behavioral intentions, we submitted participants’ estimates of how long they planned to engage in the target activity over the following week to an analogous regression model. This analysis revealed a significant effect of experimental condition on behavioral intentions (β = 0.30, SE = 0.16, p = .02, 95% CI = [0.08, 0.72]); see Figure 4. In each case, the pattern of means suggested that, as hypothesized, participants in the feedback condition reported greater behavioral intentions.

Figure 4.

Study 3: Participants who were randomly assigned to receive bogus feedback suggesting their spontaneous thoughts about a target activity were especially positive planned to devote more time to that activity in the coming week than participants who received no feedback

Note: Consistent with our prediction, a simple linear regression analysis (following a Poisson distribution) revealed a significant effect of feedback on intended duration of behavior, such that participants who received the bogus feedback (n = 40) planned to devote more time to the target activity in the coming week than participants who received no feedback (n = 40). Error bars denote ± 1 standard error.

Discussion

In the present study, we explored the process by which positive spontaneous thoughts may drive appetitive behavior, specifically testing whether mere perceptions of spontaneous thoughts as especially positive may energize wanting. Although self-reports of “wanting” were not affected by the manipulation, other outcome measures suggest that merely believing that one’s spontaneous thoughts about a particular activity are especially positive is sufficient to alter one’s plans to engage in that activity in the coming week.

The theoretical model at the heart of this endeavor suggests that positive spontaneous thoughts should amplify wanting and motivate appetitive behavior. It remained unclear, however, whether this step proceeds nonconsciously or whether some conscious awareness and possibly even active contemplation of one’s own thoughts contribute to the effects on behavior. Our primary prediction was that participants who were led to believe their spontaneous thoughts about a target activity were notably positive would demonstrate increases in wanting and plan to engage in that activity more, compared to participants who held no such belief. This pattern of results would suggest that meta-cognitive evaluations may play a role in driving behavior. Although no change in subjective wanting was observed, participants who received the false feedback reported that they intended to devote more time to the target activity in the coming week, relative to those in the control condition. Future research will be needed to identify whether similar mechanisms drive this process in more ecologically valid contexts. For example, if perceptions (accurate or not) of one’s thoughts about an activity can alter behavior, could contemplating or savoring positive spontaneous thoughts as they arise in daily life have a similar behavioral effect?

This study also begins to address the question of how positive spontaneous thoughts are related to incentive salience. As articulated previously, positive spontaneous thoughts may simply be epiphenomenal to incentive salience; they are amusing or interesting at most, but they are little more than side effects with no causal effect on behavior. On the other hand, positive spontaneous thoughts may be an active mechanism through which incentive salience facilitates appetitive behavior. Whereas Study 2 did not demonstrate an effect of positive spontaneous thoughts on behavior, the results of the present study suggest that when these thoughts are perceived as especially positive, they may indeed cultivate approach motivation, at least at the level of behavioral intentions.

Although this study represents a promising step toward understanding how positive spontaneous thoughts may facilitate appetitive behavior, important questions linger. First, the current research only goes as far as intentions, and it is not clear whether the experimental differences would span the intention-behavior gap (Sheeran, 2002) to influence actual behavior. Second, this experiment explores how perceptions of positive spontaneous thoughts – rather than positive spontaneous thoughts themselves – may influence approach motivation. On the one hand, this design offers insight about whether conscious awareness and perception may be involved in the effect of positive spontaneous thoughts on approach behavior. However, it also sidesteps the direct question of how positive spontaneous thoughts themselves may influence wanting, which remains to be tested in an experimental paradigm. Third, the results from this study demonstrate an effect of positive spontaneous thoughts on behavioral intentions but not subjective wanting, which suggests a need to carefully consider distinctions between intentions (which are arguably more closely related to behavior) and wanting. All three studies reported herein included a focus on wanting, given its prominence in the incentive-salience model, although future research should explore alternative pathways through which positive spontaneous thoughts influence approach behavior.