Abstract

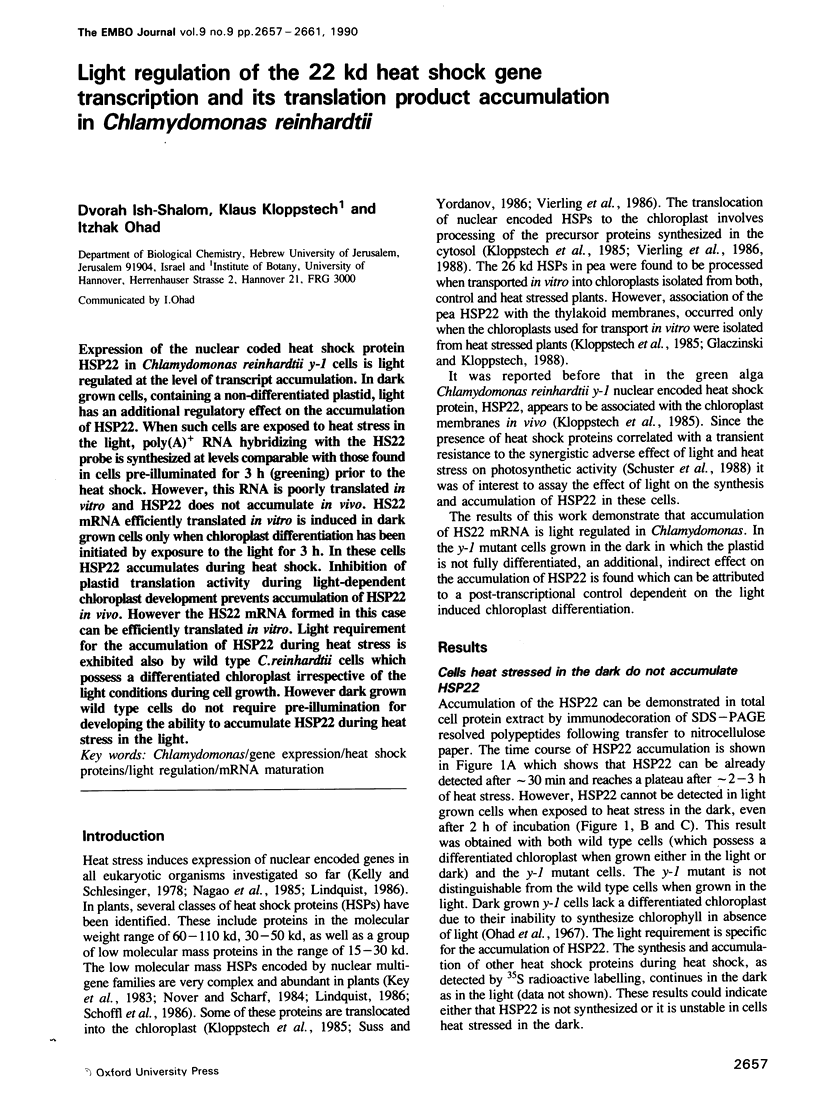

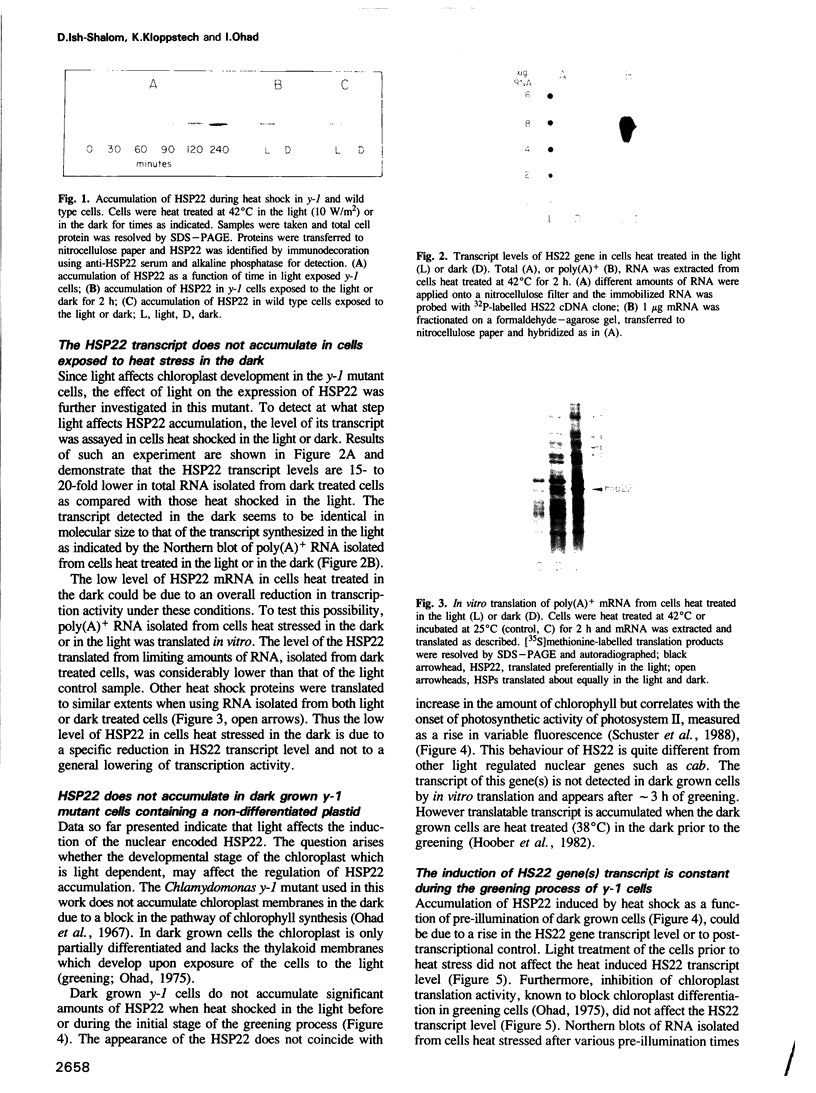

Expression of the nuclear coded heat shock protein HSP22 in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii y-1 cells is light regulated at the level of transcript accumulation. In dark grown cells, containing a non-differentiated plastid, light has an additional regulatory effect on the accumulation of HSP22. When such cells are exposed to heat stress in the light, poly(A)+ RNA hybridizing with the HS22 probe is synthesized at levels comparable with those found in cells pre-illuminated for 3 h (greening) prior to the heat shock. However, this RNA is poorly translated in vitro and HSP22 does not accumulate in vivo. HS22 mRNA efficiently translated in vitro is induced in dark grown cells only when chloroplast differentiation has been initiated by exposure to the light for 3 h. In these cells HSP22 accumulates during heat shock. Inhibition of plastid translation activity during light-dependent chloroplast development prevents accumulation of HSP22 in vivo. However the HS22 mRNA formed in this case can be efficiently translated in vitro. Light requirement for the accumulation of HSP22 during heat stress is exhibited also by wild type C. reinhardtii cells which possess a differentiated chloroplast irrespective of the light conditions during cell growth. However dark grown wild type cells do not require pre-illumination for developing the ability to accumulate HSP22 during heat stress in the light.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Apel K., Kloppstech K. The plastid membranes of barley (Hordeum vulgare). Light-induced appearance of mRNA coding for the apoprotein of the light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b protein. Eur J Biochem. 1978 Apr 17;85(2):581–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batschauer A., Mösinger E., Kreuz K., Dörr I., Apel K. The implication of a plastid-derived factor in the transcriptional control of nuclear genes encoding the light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b protein. Eur J Biochem. 1986 Feb 3;154(3):625–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond U. Heat shock but not other stress inducers leads to the disruption of a sub-set of snRNPs and inhibition of in vitro splicing in HeLa cells. EMBO J. 1988 Nov;7(11):3509–3518. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell D. C., Emerson C. P., Jr The role of cap methylation in the translational activation of stored maternal histone mRNA in sea urchin embryos. Cell. 1985 Sep;42(2):691–700. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirgwin J. M., Przybyla A. E., MacDonald R. J., Rutter W. J. Isolation of biologically active ribonucleic acid from sources enriched in ribonuclease. Biochemistry. 1979 Nov 27;18(24):5294–5299. doi: 10.1021/bi00591a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choquet Y., Goldschmidt-Clermont M., Girard-Bascou J., Kück U., Bennoun P., Rochaix J. D. Mutant phenotypes support a trans-splicing mechanism for the expression of the tripartite psaA gene in the C. reinhardtii chloroplast. Cell. 1988 Mar 25;52(6):903–913. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoni J. M., Ohad I. Chloroplast-cytoplasmic interrelations involved in chloroplast development in Chlamydomonas reinhardi y-1: effect of selective depletion of chloroplast translates. J Cell Biol. 1980 Oct;87(1):124–131. doi: 10.1083/jcb.87.1.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaczinski H., Kloppstech K. Temperature-dependent binding to the thylakoid membranes of nuclear-coded chloroplast heat-shock proteins. Eur J Biochem. 1988 May 2;173(3):579–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M. R. Pre-mRNA processing and mRNA nuclear export. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1989 Jun;1(3):519–525. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(89)90014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm B., Ish-Shalom D., Even D., Glaczinski H., Ottersbach P., Ohad I., Kloppstech K. The nuclear-coded chloroplast 22-kDa heat-shock protein of Chlamydomonas. Evidence for translocation into the organelle without a processing step. Eur J Biochem. 1989 Jul 1;182(3):539–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoober J. K., Marks D. B., Keller B. J., Margulies M. M. Regulation of accumulation of the major thylakoid polypeptides in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii y-1 at 25 degrees C and 38 degrees C. J Cell Biol. 1982 Nov;95(2 Pt 1):552–558. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.2.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley P. M., Schlesinger M. J. The effect of amino acid analogues and heat shock on gene expression in chicken embryo fibroblasts. Cell. 1978 Dec;15(4):1277–1286. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloppstech K., Meyer G., Schuster G., Ohad I. Synthesis, transport and localization of a nuclear coded 22-kd heat-shock protein in the chloroplast membranes of peas and Chlamydomonas reinhardi. EMBO J. 1985 Aug;4(8):1901–1909. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03869.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S. The heat-shock response. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:1151–1191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield S. P., Taylor W. C. Carotenoid-deficient maize seedlings fail to accumulate light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b binding protein (LHCP) mRNA. Eur J Biochem. 1984 Oct 1;144(1):79–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestril R., Schiller P., Amin J., Klapper H., Ananthan J., Voellmy R. Heat shock and ecdysterone activation of the Drosophila melanogaster hsp23 gene; a sequence element implied in developmental regulation. EMBO J. 1986 Jul;5(7):1667–1673. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao R. T., Czarnecka E., Gurley W. B., Schöffl F., Key J. L. Genes for low-molecular-weight heat shock proteins of soybeans: sequence analysis of a multigene family. Mol Cell Biol. 1985 Dec;5(12):3417–3428. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.12.3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville D. M., Jr Molecular weight determination of protein-dodecyl sulfate complexes by gel electrophoresis in a discontinuous buffer system. J Biol Chem. 1971 Oct 25;246(20):6328–6334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nover L., Scharf K. D. Synthesis, modification and structural binding of heat-shock proteins in tomato cell cultures. Eur J Biochem. 1984 Mar 1;139(2):303–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohad I., Siekevitz P., Palade G. E. Biogenesis of chloroplast membranes. II. Plastid differentiation during greening of a dark-grown algal mutant (Chlamydomonas reinhardi). J Cell Biol. 1967 Dec;35(3):553–584. doi: 10.1083/jcb.35.3.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddihough G., Pelham H. R. Activation of the Drosophila hsp27 promoter by heat shock and by ecdysone involves independent and remote regulatory sequences. EMBO J. 1986 Jul;5(7):1653–1658. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04408.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts B. E., Paterson B. M. Efficient translation of tobacco mosaic virus RNA and rabbit globin 9S RNA in a cell-free system from commercial wheat germ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973 Aug;70(8):2330–2334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.8.2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster G., Even D., Kloppstech K., Ohad I. Evidence for protection by heat-shock proteins against photoinhibition during heat-shock. EMBO J. 1988 Jan;7(1):1–6. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02776.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierling E., Mishkind M. L., Schmidt G. W., Key J. L. Specific heat shock proteins are transported into chloroplasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Jan;83(2):361–365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.2.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierling E., Nagao R. T., DeRocher A. E., Harris L. M. A heat shock protein localized to chloroplasts is a member of a eukaryotic superfamily of heat shock proteins. EMBO J. 1988 Mar;7(3):575–581. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02849.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost H. J., Lindquist S. RNA splicing is interrupted by heat shock and is rescued by heat shock protein synthesis. Cell. 1986 Apr 25;45(2):185–193. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90382-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gromoff E. D., Treier U., Beck C. F. Three light-inducible heat shock genes of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Sep;9(9):3911–3918. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.9.3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]