Abstract

Peritoneal mesothelioma (MPeM) is a scarce abdominal-pelvic malignancy that presents with non-specific features and exhibits a wide clinical spectrum from indolent to aggressive disease. Due to it being a rare entity, there is a lack of understanding of its molecular drivers. Most treatment data are from limited small studies or extrapolated from pleural mesothelioma. Standard treatment includes curative surgery or pemetrexed-platinum palliative chemotherapy. To date, the use of novel targeted agents has been disappointing.

Described is the management of two young women with papillary peritoneal mesothelioma with widespread recurrence having received platinum-pemetrexed chemotherapy. Both patients obtained symptomatic and disease benefit with apitolisib, a dual phosphoinositide 3-kinase-mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K-mTOR) inhibitor for subsequent relapses, with one patient having a partial response for almost 3 years. Both are alive and well 10–13 years from diagnosis.

Conclusion

These case presentations highlight a subgroup of rare MPeM that behave indolently that is compatible with long-term survival. This series identifies the use of targeted therapies with PI3K-mTOR-based inhibitors as a novel approach, warranting further clinical assessment. Development of prognostic biomarkers is essential to aid identify tumour aggressiveness, help stratify patients and facilitate treatment decisions.

Keywords: Peritoneal mesothelioma, PI3K, mTOR, Apitolisib, Therapy

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma is a rare clinical entity with few clinical trials being undertaken and most data derived from its pleural counterpart. Platinum-pemetrexed chemotherapy is the standard therapy and studies with novel targeted agents have been disappointing.

What does this study add?

These cases demonstrate significant sustained clinical benefit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase-mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K-mTOR) inhibition in peritoneal cases without PIK3CA mutations or phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) loss.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

This highlights a novel therapeutic strategy by targeting the PI3K-PTEN-AKT-mTOR signalling network and should encourage recruitment of peritoneal mesothelioma patients to early phase clinical studies.

Introduction

Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPeM) is a rare malignancy, accounting for 30% of all mesotheliomas.1 In contrast with pleural mesothelioma (MPM), it is common in younger women, often exhibiting a more indolent course with long-term survivors.2 3 Asbestos exposure is the prime risk factor for MPM, however, the evidence for its association with peritoneal disease is much weaker.4–6

Epithelioid, sarcomatoid and biphasic are the most common histological mesothelioma subtypes. Deciduoid epithelioid is a rare subtype associated with a poor prognosis.7–9 Borderline and benign variants have been described, including multicystic and well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma (WDPM). The latter, is a non-invasive subtype that occurs in women of reproductive age with no asbestos exposure, which demonstrates an indolent clinical course with a relatively good prognosis, although the potential for aggressive progression exists, thus, long-term follow-up is advocated.7 10 Due to the different clinical outcomes, WDPM should be histologically differentiated from the architecturally similar but more aggressive epithelioid papillary form.

MPeM typically presents with non-specific features, including abdominal pain, distension, palpable pelvic masses, altered bowel habit and rarely subcutaneous nodules. Constitutional symptoms such as asthenia, weight loss and fever also occur.1 11 Radiological findings suggestive of MPeM include peritoneal thickening, mesenteric nodules and omental cakes. Slow-growing disease is often an incidental surgical finding.1 5 11

Distant metastases are rarely associated with MPeM, thus, disease confined to the peritoneum is amenable to potentially curative cytoreductive surgery with a median overall survival of 28–35 months.5 Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy has been advocated as postoperative therapy and long-term survival can be achieved,12 13 although prospective randomised trials have not been conducted.14 Treatment for inoperable MPeM involves palliative chemotherapy with pemetrexed, cisplatin and gemcitabine alone or in combination.1 14 The former is based on data extrapolated from a large phase III pleural mesothelioma study that demonstrated a 2.8-month survival benefit with cisplatin-pemetrexed combination to 12.1 months.15 MPeM-specific studies with pemetrexed ± cisplatin include a phase II study16 and an expanded access programme in 109 patients that demonstrated a 57% 1-year survival rate with pemetrexed-cisplatin compared with 42% with pemetrexed alone.17 Additionally, a phase II study in 26 patients using pemetrexed and gemcitabine combination showed promising results with median overall survival of 26.8 months.18 Given the paucity of peritoneal randomised trials, this regimen is the accepted standard first-line therapy for metastatic MPeM.

Recent trials in pleural mesothelioma using novel targeted agents have been disappointing, despite promising preclinical data. Phase II studies using agents targeting the epidermal and vascular endothelial growth factor receptors have yielded little promise.19–21 Neither has the use of vorinostat, a histone deactylase (HDAC) inhibitor, nor the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus.22–24 Improved understanding of the pathogenesis and molecular drivers of MPeM is warranted, in order to elucidate new therapeutic options in this poorly understood disease.

Activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN)-AKT-mTOR signalling network, a critical driver of oncogenesis, has been reported in mesothelioma through loss of PTEN function, reported in 30%–60%,25 26 and somatic mutations in the neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) in up to half of malignant mesothelioma cases.27 Thus, pharmacological inhibition of the PI3K-PTEN-AKT-mTOR pathways could provide putative therapeutic benefit in mesothelioma. Herein, we report two patients with MPeM who were treated with apitolisib, a dual class I PI3K, mTORC 1 and 2 inhibitor.28 This agent has shown promise particularly in patients with mesothelioma in early phase studies. Three-quarters of the partial responses in the dose escalation phase were in patients with mesothelioma (one peritoneal and two pleural) with a 12% partial response rate confirmed in the phase II expansion.29 These cases show that PI3K-mTOR inhibitors may offer novel treatment strategies after palliative chemotherapy, enabling long-term survival despite disease recurrence.

Case reports

Two female patients treated at the Royal Marsden Hospital, London, UK are described. All patients provided written consent for research publications.

Case 1

A female aged 28 years presented with abdominal pain, percutaneous biopsy of a 15 cm pelvic mass was reported as a benign highly differentiated adenomatous tumour (table 1). At laparotomy the lesion was only amenable to partial resection. Final histology confirmed papillary MPeM. She received four cycles of adjuvant cisplatin-pemetrexed chemotherapy followed by pelvic radiotherapy and brachytherapy. Following a 2-year disease-free interval, further pelvic recurrence was resected with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and appendicectomy, followed by four cycles of cisplatin-pemetrexed and MRI surveillance thereafter. Inoperable pelvic progression occurred after 2 years and was rechallenged with eight cycles of carboplatin-pemetrexed, with stable disease. The third relapse occurred after 1.5 years, 6.5 years from diagnosis, and the patient commenced a phase I trial with the PI3K-mTOR kinase inhibitor, apitolisib.28 30 She received over 2.5 years of this agent with minimal toxicity and good symptomatic benefit. The CA-125 fell from 217 to 32 and a confirmed partial radiological response was detected. Interestingly, intermittent interruption of apitolisib dosing for toxicities during the intrapatient dose escalation was mirrored with a rise in the CA-125 and radiological evidence of minor growth, which was then suppressed following reinitiation of treatment. After 2.8 years, slow progression ensued and she was taken off study and actively monitored for 5 months before developing new peritoneal metastases. She was enrolled into a second phase I trial with the combination of a poly-ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP)31 and an AKT inhibitor. This was well tolerated, the CA-125 fell from 200 to 69. However, after 6 months she had slowly progressive disease. She is alive and well 13 years after diagnosis.

Table 1.

Case series overview: clinical presentation, treatment modality, best tumour marker, radiological response and time to progression*.

| Case | Age | Clinical presentation | Line of treatment | Treatment type | Best CA-125 response | Best radiological response | TTP (mo) | Time from diagnosis to last follow-up (mo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28 | Abdominalpain and 15 cm pelvic mass | 1st | Optimal tumour debulking, 4 cis-pem, pelvic RT and brachytherapy | NK | SD | 23 | |

| 2nd | Surgery, 4 cis-pem | NK | SD | 30 | ||||

| 3rd | 8 carbo-pem | 38→21 | SD | 17 | ||||

| 4th | 2.8 years PI3K-mTOR inhibitor | 217→32 | cPR | 34 | ||||

| 5th | 6 mo PARP-AKT inhibitor | 200→69 | SD | AWD | 156 | |||

| 2 | 19 | Vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain and distension | 1st | 4 cis-pem | NK | SD | 35 | |

| 2nd | 4 cis-pem | NK | SD | 11 | ||||

| 3rd | 2 mo HDAC inhibitor | NK | SD | 5 | ||||

| 4th | 15 mo PI3K-mTOR inhibitor | 200→172 | SD | AWD | 123 |

*TTP, time to progression; mo, months; SD, stable disease; cPR, confirmed partial response; AWD, alive with disease; RT, radiotherapy; cis, cisplatin; carbo, carboplatin; pem, pemetrexed; PI3K, phosphatidyl-3-kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PARP, poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase; HDAC, histone deacetylase; NK, not known.

Case 2

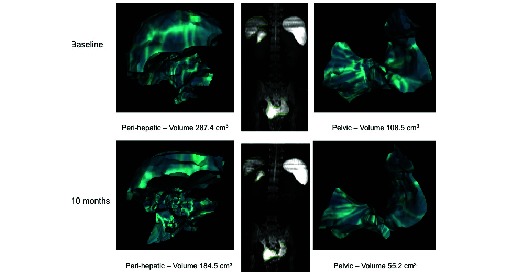

A female aged 19 years presented with vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain and distension; CT scan confirmed large volume pelvic and peritoneal disease (table 1). The omental mass was laparoscopically resected and histopathology confirmed a WDPM. She became pregnant almost immediately after diagnosis, hence was monitored until delivery of a healthy child. The disease progressed 1 year after diagnosis and was considered inoperable; therefore, she commenced four cycles of cisplatin-pemetrexed with stable disease. Further progression occurred 2 years later, disease stability was obtained with rechallenge of four further cycles of cisplatin-pemetrexed. The third significant progression occurred after 1 year and she enrolled into two sequential phase I trials. The first with an oral HDAC inhibitor that was terminated early due to cardiotoxicity. The second with apitolisib, which she received for 15 months with significant tumour regression (27% decrease), overall stable disease by the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST). The use of MRI volumetric assessment demonstrates a significant reduction of the large burden peritoneal disease by 39% (figure 1), highlighting the superiority of MRI imaging in this type of disease. She continues on follow-up with disease control without requiring further treatment to date. She remains alive, 10 years following initial presentation and has recently given birth to a healthy second child.

Figure 1.

Case 2—volumetric MRI tumour measurements of perihepatic and pelvic mesothelioma demonstrating a 39% reduction in tumour volume after 10 months treatment with apitolisib.

Discussion

Despite the majority of patients with MPeM demonstrating an aggressive biological phenotype, these cases highlight the potential for some cases of invasive epithelioid mesothelioma in younger women to behave indolently. Both patients are still alive with follow-up ranging from 123 to 156 months. These cases exhibit different MPeM histological subtypes (one papillary, one WDPM), but all appear slow growing. Some studies have suggested a cohort of MPeMs have a different biological behaviour compatible with long-term survival, but such cases cannot be identified on the basis of histology alone. Platinum-pemetrexed chemotherapy was the treatment backbone for both patients that led to disease stability.

Both patients subsequently achieved tumour shrinkage with apitolisib, the PI3K-mTOR inhibitor. Case 1 had symptomatic improvement, normalisation of the CA-125, a maintained radiological partial response and remained on treatment for 2.8 years. Case 2 received 15 months of apitolisib with significant tumour reduction of almost a third by RECIST and 40% using volumetric measurements. Molecular sequencing was undertaken to ascertain the reason for their responses. No mutations were detected in the 19 most common oncogenes tested using the prevalidated Sequenom panel V.1.0, specifically no PIK3CA or RAS/RAF mutations were evident. Also, no PTEN loss was evident by immunohistochemistry.29 Notably, no assays to assess NF2 have been undertaken, this would be interesting to know as mutations can occur in up to half of mesothelioma cases27 and could account for sensitivity to PI3K-mTOR pathway blockade. Another molecular change that would be interesting to assess is the BRCA-associated protein 1 (BAP1), a tumour suppressor, in which somatic mutations occur up to 60% in mesothelioma.32 33

Much of the data for peritoneal mesothelioma is derived from the pleural counterpart, however, should these be considered similar biological entities? Furthermore, in-depth molecular characterisation of these patients is required to elucidate the oncogenic drivers of MPeM. Targeting the loss of function of tumour suppressors PTEN and NF2 is pharmacologically challenging, and new efforts are needed through inhibition of synthetic lethal targets or other approaches such as targeting ubiquitin-mediated destruction or epigenetic gene silencing. The latter is mediated through the HDAC family that reduce DNA transcription through histone modifications. HDAC overexpression has been documented in MPM, but large-scale evaluation of the best-studied HDAC inhibitor, vorinostat, failed to show survival benefits in pleural mesothelioma; more specific HDAC inhibitors may be needed. In addition, prognostic biomarkers are needed to identify aggressiveness in tumour biology necessitating early treatment from the more indolent cases.

The CA-125 tumour marker is often elevated in peritoneal mesothelioma and has been associated with massive peritoneal involvement.6 Among CA-125 secretors, it can be used as a sensitive marker that correlates with the extent of debulking surgery and also in assessing disease progression.34 In our series, CA-125 mirrored the radiological and clinical course of the disease. However, multiple marker fluctuations occurred on treatment without obvious corroborative radiological evidence of disease alteration. Therefore, it remains undetermined whether CA-125 can be considered a reliable marker in indolent MPeM. More novel tumour markers are under investigation such as mesothelin, mesothelin-related proteins and osteopontin.35–37

This case series highlights the challenging nature of the initial diagnosis of peritoneal mesothelioma, given the non-specific symptoms coupled with difficulties in making an accurate diagnosis based on histology. MPeM in female patients shows similarity with epithelial ovarian, tubal and peritoneal cancer, leading to further diagnostic quandary. From our experience, laparoscopic biopsies were the most reliable approach to ensure the correct diagnosis and specific histological subtype was confirmed which is essential to facilitate the optimal clinical management.

Both cases were monitored by routine CT scans. MRI scans can provide more detailed assessment of diffuse peritoneal disease; it is especially useful during the follow-up period in order to identify significant disease progression in the context of slowly enlarging disease and to help determine when to instigate treatment. In addition, there is an increasing body of evidence supporting the use of diffusion-weighted MRI. Radiological assessment of MPeM can be challenging and RECIST criteria may not be the optimal radiological tool due to the diffuse pattern and often small-volume disease.

Many of these patients had slow progression over many years despite recurrences, and the question is when to initiate treatment? Both cases showed demonstrable clinical benefit and tumour shrinkage with frequent rechallenges of anticancer therapies. Generally, chemotherapy does not seem to cause significant tumour shrinkage, suggesting that MPeM is not particularly chemosensitive. Targeting the PI3K-AKT-mTOR axis has shown promising antitumour activity in two patients treated within our series. Newer experimental agents are obviously needed and are being investigated. The combination of a PARP inhibitor with an AKT inhibitor may merit further exploration; based on preclinical data suggesting that the combination can increase PARP inhibitor sensitivity. Other approaches could include targeting mesothelin itself and specific drug-related conjugates are now in clinical trial. Clearly, further research is warranted into optimal MPeM treatments, timing and the development of prognostic and therapeutic biomarkers that will hopefully translate into superior clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, these cases highlight the importance of obtaining the correct histological diagnosis to tailor treatment and to dissect out the indolent from the more aggressive subtypes. This must be carefully correlated with symptomatic and radiological changes to drive treatment decisions. Chemotherapy remains the backbone of treatment, and can offer long-term disease control. The molecular understanding of this condition is poor, which correlates with the paucity of biological treatment options available. These cases highlight the clinical success of the use of apitolisib, the PI3K-mTOR inhibitor, deriving symptomatic benefit and sustained tumour shrinkage. Moreover, this provides a much-needed novel therapeutic approach in this rare disease entity that warrants further clinical evaluation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Royal Marsden/Institute of Cancer Research Biomedical Research Centre for Cancer and the National Institute for Health Research. No financial report was received.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Mirarabshahii P, Pillai K, Chua TC, et al. . Diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma-an update on treatment. Cancer Treat Rev 2012;38:605–12. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kindler HL. Peritoneal mesothelioma: the site of origin matters. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2013:182–8. 10.1200/EdBook_AM.2013.33.182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yan TD, Popa E, Brun EA, et al. . Sex difference in diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Br J Surg 2006;93:1536–42. 10.1002/bjs.5377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boffetta P. Epidemiology of peritoneal mesothelioma: a review. Ann Oncol 2007;18:985–90. 10.1093/annonc/mdl345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chua TC, Yan TD, Morris DL. Surgical biology for the clinician: peritoneal mesothelioma: current understanding and management. Can J Surg 2009;52:59–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carbone M, Ly BH, Dodson RF, et al. . Malignant mesothelioma: facts, myths, and hypotheses. J Cell Physiol 2012;227:44–58. 10.1002/jcp.22724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Husain AN, Colby T, Ordonez N, et al. ; International Mesothelioma Interest Group. Guidelines for pathologic diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma: 2012 update of the consensus statement from the International Mesothelioma Interest Group. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2013;137:647–67. 10.5858/arpa.2012-0214-OA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mourra N, de Chaisemartin C, Goubin-Versini I, et al. . Malignant deciduoid mesothelioma: a diagnostic challenge. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2005;129:403–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ordóñez NG. Deciduoid mesothelioma: report of 21 cases with review of the literature. Mod Pathol 2012;25:1481–95. 10.1038/modpathol.2012.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Galateau-Sallé F, Vignaud JM, Burke L, et al. ; Mesopath group. Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma of the pleura: a series of 24 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:534–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Munkholm-Larsen S, Cao CQ, Yan TD. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. World J Gastrointest Surg 2009;1:38–48. 10.4240/wjgs.v1.i1.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yano H, Moran BJ, Cecil TD, et al. . Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal mesothelioma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2009;35:980–5. 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deraco M, Nonaka D, Baratti D, et al. . Prognostic analysis of clinicopathologic factors in 49 patients with diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma treated with cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion. Ann Surg Oncol 2006;13:229–37. 10.1245/ASO.2006.03.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kotova S, Wong RM, Cameron RB. New and emerging therapeutic options for malignant pleural mesothelioma: review of early clinical trials. Cancer Manag Res 2015;7:51–63. 10.2147/CMAR.S72814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vogelzang NJ, Rusthoven JJ, Symanowski J, et al. . Phase III study of pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:2636–44. 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jänne PA, Wozniak AJ, Belani CP, et al. . Open-label study of pemetrexed alone or in combination with cisplatin for the treatment of patients with peritoneal mesothelioma: outcomes of an expanded access program. Clin Lung Cancer 2005;7:40–6. 10.3816/CLC.2005.n.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carteni G, Manegold C, Garcia GM, et al. . Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma-Results from the International Expanded Access Program using pemetrexed alone or in combination with a platinum agent. Lung Cancer 2009;64:211–8. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Simon GR, Verschraegen CF, Jänne PA, et al. . Pemetrexed plus gemcitabine as first-line chemotherapy for patients with peritoneal mesothelioma: final report of a phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3567–72. 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Garland LL, Rankin C, Gandara DR, et al. . Phase II study of erlotinib in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: a Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:2406–13. 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.7634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Govindan R, Kratzke RA, Herndon JE, et al. ; Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 30101). Gefitinib in patients with malignant mesothelioma: a phase II study by the Cancer and leukemia group B. Clin Cancer Res 2005;11:2300–4. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kindler HL, Karrison TG, Gandara DR, et al. . Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase II trial of gemcitabine/cisplatin plus bevacizumab or placebo in patients with malignant mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2509–15. 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.5869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Krug LM, Curley T, Schwartz L, et al. . Potential role of histone deacetylase inhibitors in mesothelioma: clinical experience with suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid. Clin Lung Cancer 2006;7:257–61. 10.3816/CLC.2006.n.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ramalingam SS, Belani CP, Ruel C, et al. . Phase II study of belinostat (PXD101), a histone deacetylase inhibitor, for second line therapy of advanced malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:97–101. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318191520c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Garland LL, Ou S, Moon J, et al. . SWOG 0722: a phase II study of mTOR inhibitor everolimus (RAD001) in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM). J Clin Oncol 2012;30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Opitz I, Soltermann A, Abaecherli M, et al. . PTEN expression is a strong predictor of survival in mesothelioma patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;33:502–6. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.09.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Agarwal V, Campbell A, Beaumont KL, et al. . PTEN protein expression in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Tumour Biol 2013;34:847–51. 10.1007/s13277-012-0615-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Carbone M, Yang H. Molecular pathways: targeting mechanisms of asbestos and erionite carcinogenesis in mesothelioma. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:598–604. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wallin JJ, Edgar KA, Guan J, et al. . GDC-0980 is a novel class I PI3K/mTOR kinase inhibitor with robust activity in cancer models driven by the PI3K pathway. Mol Cancer Ther 2011;10:2426–36. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dolly SO, Wagner AJ, Bendell JC, et al. . Phase I Study of Apitolisib (GDC-0980), Dual Phosphatidylinositol-3-Kinase and Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Kinase Inhibitor, in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:2874–84. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dolly SO, Krug LM, Wagner AJ, et al. . Evaluation of tolerability and antitumour activity of GDC-0980, an oral PI3K/MTOR inhibitor, administered to patients with advanced malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM). J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:s2. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kaye SB, Lubinski J, Matulonis U, et al. . Phase II, open-label, randomized, multicenter study comparing the efficacy and safety of olaparib, a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and recurrent ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:372–9. 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.9215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bott M, Brevet M, Taylor BS, et al. . The nuclear deubiquitinase BAP1 is commonly inactivated by somatic mutations and 3p21.1 losses in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Nat Genet 2011;43:668–72. 10.1038/ng.855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yoshikawa Y, Sato A, Tsujimura T, et al. . Frequent inactivation of the BAP1 gene in epithelioid-type malignant mesothelioma. Cancer Sci 2012;103:868–74. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02223.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baratti D, Kusamura S, Martinetti A, et al. . Circulating CA125 in patients with peritoneal mesothelioma treated with cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:500–8. 10.1245/s10434-006-9192-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shiomi K, Hagiwara Y, Sonoue K, et al. . Sensitive and specific new enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for N-ERC/mesothelin increases its potential as a useful serum tumor marker for mesothelioma. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14:1431–7. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Robinson BW, Creaney J, Lake R, et al. . Mesothelin-family proteins and diagnosis of mesothelioma. Lancet 2003;362:1612–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14794-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pass HI, Lott D, Lonardo F, et al. . Asbestos exposure, pleural mesothelioma, and serum osteopontin levels. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1564–73. 10.1056/NEJMoa051185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]