Abstract

A high‐valent Fe(IV) species is proposed to be generated from the decay of a peroxodiferric intermediate in the catalytic cycle at the di‐iron cofactor center of dioxygen‐activating enzymes such as methane monooxygenase. However, it is believed that this intermediate is not formed in the di‐iron substrate site of ferritin, where oxidation of Fe(II) substrate to Fe(III) (the ferroxidase reaction) occurs also via a peroxodiferric intermediate. In opposition to this generally accepted view, here we present evidence for the occurrence of a high‐valent Fe(IV) in the ferroxidase reaction of an archaeal ferritin, which is based on trapped intermediates obtained with the freeze‐quench technique and combination of spectroscopic characterization. We hypothesize that a Fe(IV) intermediate catalyzes oxidation of excess Fe(II) nearby the ferroxidase center.

Keywords: Fe(IV), ferritin, ferroxidase, peroxodiferric, tyrosine radical

Abbreviations

EPR, electron paramagnetic resonance

MMO, methane monooxygenase

PfFtn, Pyrococcus furiosus ferritin

RNR, ribonucleotide reductase

SVD, singular value decomposition

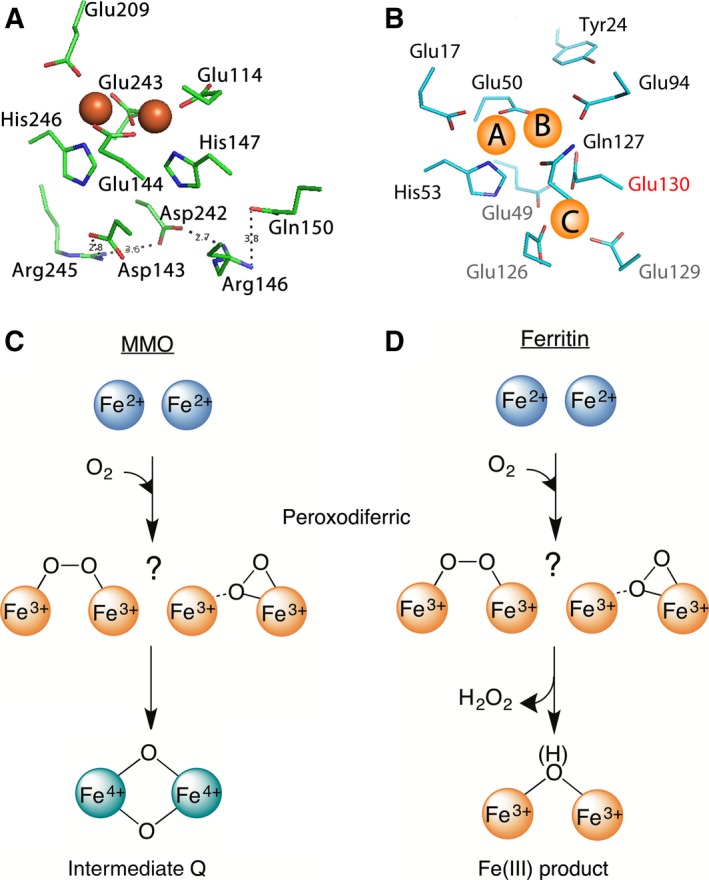

A di‐iron catalytic center is key to the functioning of ferritin, the ubiquitous iron‐storage protein of life 1. Unlike the di‐iron cofactor site in dioxygen‐activating enzymes, the di‐iron center in ferritin catalyzes the oxidation of Fe(II) as substrate. This di‐iron catalytic site, which is known as the ferroxidase center, has three major structural differences with the di‐iron cofactor site of dioxygen‐activating enzymes (Fig. 1A–B): (a) the ferroxidase center has only one coordinating glutamate as bridging ligand, (b) there is a Fe(II) binding site next to the ferroxidase center (site C), which is replaced by a network of hydrogen bonds in the di‐iron cofactor site of dioxygen activating enzymes like methane monooxygenase (MMO) 2, and (c) in ferritins one active site residue that is not conserved (Glu130 in Pfu Ftn) 1, is a conserved histidine coordinating one of the Fe atoms in the di‐iron cofactor site of dioxygen‐activating enzymes. Nevertheless, during catalysis both in the di‐iron cofactor site of dioxygen‐activating enzymes 3 and in the ferroxidase center 4, 5 a peroxodiferric intermediate is formed (Fig. 1C–D). In dioxygen‐activating enzymes such as MMO 3, 6 when the substrate is present, the peroxodiferric intermediate rapidly oxidizes the substrate, but in the absence of a substrate it generates intermediate Q (Fig. 1C), an antiferromagnetically coupled di‐iron Fe(IV) species 3. The molecular structure of the peroxodiferric species in MMO is still unknown 3 and Q is proposed to have a bis‐μ‐oxo diamond core 7. In contrast, it is generally believed that the peroxodiferric species in ferritin decays directly to Fe(III) products 4, 5, 8, 9 (Fig. 1D) and a high‐valent Fe(IV) species has never been reported. The exact molecular structure of the peroxodiferric intermediate in ferritin is under debate 1, 10. While it was originally proposed that the dioxygen in the peroxodiferric species has a μ‐1,2 bonding mode 5, 11, recent data obtained by X‐ray crystallography 12 and Mössbauer spectroscopy 10 suggest a μ‐η1‐η2 bonding mode.

Figure 1.

The di‐iron cofactor site of dioxygen‐activating enzymes is different from the di‐iron substrate site of ferritin. (A) The coordinating residues of the di‐iron cofactor site of MMO (PDB 1FYZ) are compared with (B) those of the di‐iron substrate site (the ferroxidase center) of PfFtn (PDB 2JD7). Three main differences are observed (see text). (C) In the di‐iron cofactor site of MMO the peroxodiferric intermediate (two possible molecular structures are shown) decays to intermediate Q, an antiferromagnetically coupled di‐iron Fe(IV) species with a bis‐μ‐oxo diamond core. (D) In ferritin, however, it is believed that the peroxodiferric intermediate directly decays to Fe(III) products.

We have used Pyrococcus furiosus ferritin (PfFtn) to further characterize the possible intermediate species involved in catalysis of Fe(II) oxidation. PfFtn was chosen because the optimum reaction temperature of this protein is ~ 100 °C, and in mechanistic studies at temperatures below, for example, 50 °C, the reaction rate will be slowed down by more than one order of magnitude. Consequently, there will be a higher chance to resolve possible short‐lived intermediates during the catalytic cycle of the protein. We combined the freeze‐quench technique with electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) and Mössbauer spectroscopy to trap and characterize the intermediates of the reaction. We have identified a new species whose spectroscopic characteristics are consistent with a high‐valent Fe(IV).

Results

Evidence for the presence of a new intermediate in the ferroxidase reaction

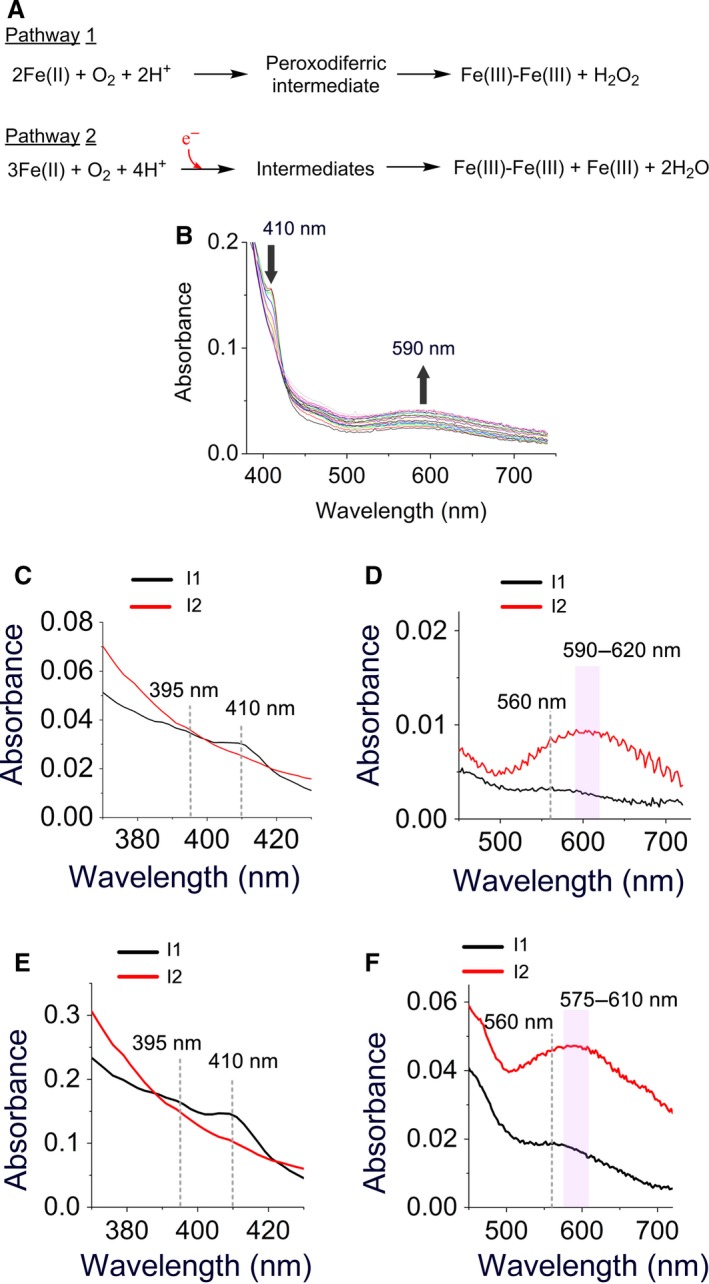

Previously, we showed that due to the presence of three distinct Fe(II)‐binding sites (Fig. 1B) with potentially variable occupancy patterns 1, 2, 10, 13, at least two parallel pathways for catalysis of Fe(II) oxidation exist (Fig. 2A) 1, 13: a pathway for subunits in which only sites A and B are occupied with Fe(II) ions (AIIBIIC0 subunits; pathway 1 in Fig. 2A) and a pathway for subunits in which sites A, B, and C are all occupied with Fe(II) ions (AIIBIICII subunits; pathway 2 in Fig. 2A). Mössbauer spectroscopy showed that in PfFtn upon the addition of 48 Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer ~ 80–82% of Fe(II) ions fill sites A and B, and about 18–19% of Fe(II) ions fill site C. Based on the affinity of each site for Fe(II) and an statistical model it was shown that ~ 56% of subunits is in the AIIBIIC0 form and 32% is in the AIIBIICII form 10. In the AIIBIIC0 subunits Fe(II) is oxidized via the peroxodiferric intermediate to form the Fe(III) products and hydrogen peroxide, while in the AIIBIICII subunits two Fe(II) in the ferroxidase center and an Fe(II) in site C are somehow oxidized together to form Fe(III) products and reduce a molecule of oxygen to two water molecules 13. In this pathway a highly conserved tyrosine near the ferroxidase center provides a fourth electron for complete reduction of molecular oxygen to water. For the addition of 48 or less Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer pathway 1 predominates, and as the amount of Fe(II) added is increased more Fe(II) is being oxidized via pathway 2. In order to obtain new insight into the intermediates of each reaction pathway we measured oxidation of 48 or 96 Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer using UV‐visible stopped‐flow spectroscopy (Fig. 2B and Fig. S1), and we analyzed the data using the singular value decomposition (SVD) method (Appendix S1). The SVD analysis was based on a model for three chromophores (S→I1→I2 Appendix S1) where S is the Fe(II) substrate, I1 is the first intermediate, and I2 is the second intermediate. This model was the simplest model required for analysis of the data. The data were analyzed for the time period immediately after the addition of Fe(II) and before the broad absorbance of the intermediates between 550 and 750 nm begins to decay (Fig. S1). This is because the majority of the Fe(III) products, whose spectroscopic properties might interfere with those of Fe(III) intermediates are expected to form upon decay of the intermediates.

Figure 2.

UV‐visible stopped‐flow spectroscopy suggests the presence of a new intermediate. (A) Two possible pathways proposed for the oxidation of Fe(II) in the ferroxidase center. Pathway 1 occurs in subunits whose sites A and B only are occupied with Fe(II) (AIIBIIC0 subunits) and pathway 2 occurs in subunits whose sites A, B, and C are occupied with Fe(II) (AIIBIICII subunits). In the second pathway the highly conserved tyrosine in the ferroxidase center is proposed to provide the fourth electron for a complete reduction of molecular oxygen to water. (B) UV‐visible absorbance spectra of different intermediates recorded for 5 s after the addition of circa 96 Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer to PfFtn. Measurements were performed at 47 °C. Concentration of PfFtn was 4.5 μm, which is 10 times less than the concentration of protein used for freeze‐quench experiments. The absorbance at 410 nm disappears after 5 s while the broad absorbance between 500 and 750 increases continuously. (C–F) The UV‐visible absorbance spectra of the intermediates during catalysis of Fe(II) oxidation by PfFtn were obtained using SVD analysis. (C–D) The absorbance spectrum of the intermediates obtained for the addition of 48 Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer (4.4 μm), or (E–F) for the addition of 96 Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer (15 μm).

For the addition of 48 Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer to apo‐PfFtn the SVD analysis suggested the presence of two major intermediate species: Intermediate I1 with three bands at 395, 410, and 560 nm (black trace, Fig. 2C–D). These bands are typical of a tyrosine radical in other enzymes such as TauD 14. The absorbance at 410 nm reached its maximum within < 60 ms and subsequently, disappeared within 1 s (Fig. S1). Intermediate I2 (blue color) had a broad absorbance spectrum at 500–750 nm and centered between 590 and 620 nm (red trace, Fig. 2C–D). The absorbance of this intermediate reached its maximum ~ 2 s after the addition of Fe(II) and disappeared after more than 40 s Fig. S1.

The addition of 96 Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer led to formation of a tyrosine radical intermediate whose absorbance spectrum (intermediate I1, black trace, Fig. 2E–F) was similar to that found for the addition of 48 Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer (intermediate I1, black trace, Fig. 2C–D). However, compared to the addition of 48Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer the center of the broad absorbance spectrum between 500 and 750 nm (intermediate I2;) was shifted from ~ 590–625 nm (red trace, Fig. 2D) to ~ 575–610 nm (red trace, Fig. 2F). The reason for this observation is not known. We speculate that the second chromophore (I2) with a broad absorbance spectrum between 500 and 750 nm may be the sum of the absorbance of at least two intermediates, a peroxodiferric and a second unknown intermediate. The ratio of these intermediates changes as a function of Fe(II) added and thus, the center of the broad absorbance spectrum between 500 and 750 nm changes. One possibility for the second unknown intermediate is an Fe(IV) species observed in the di‐iron cofactor site of dioxygen‐activating enzymes.

A tyrosine radical is formed next to the ferroxidase center

We used freeze‐quench preparations (Appendix S1) to trap reaction intermediates for EPR and Mössbauer spectroscopy. The maximum amount of Fe(II) that could be added was 48 Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer because for higher iron contents there was not sufficient dissolved dioxygen present in the sample to catalyze the oxidation of all the irons 10. This was because the enzyme concentration had to be high for the freeze‐quench experiments 10. When the reaction of apo‐PfFtn with 48 Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer was quenched after circa 1.0 s, the EPR spectrum of a sample with natural abundance Fe(II) (NATFe(II)) showed an isotropic EPR signal with g = 2.0031 (Fig. S2). This signal was not observed in the absence of dioxygen suggesting that it originates from the oxidation of Fe(II) in the ferroxidase center by O2 and was similar to the tyrosine radical previously observed for oxidation of Fe(II) by Fe(III)‐loaded PfFtn 13. The spin concentration of the EPR signal was circa 3% of the total amount of Fe(II) added. We checked if the EPR signal is due to an isolated tyrosine radical. The signal at g = 2.0031 did not saturate even at low temperature and maximal microwave power (Fig. S3). This suggests that the radical species is coupled to a paramagnetic metal center. The temperature dependence of the EPR signal intensity measured under nonsaturation conditions showed Curie behavior (S = 1/2; Fig. S4). Therefore, we conclude that the EPR signal is due to a radical species coupled to iron in the ferroxidase center and not due to a free radical. This observation is consistent with our previous site‐directed mutagenesis study 13 in combination with EPR spectroscopy in which we found that the highly conserved tyrosine in the vicinity of the ferroxidase center, that is, Tyr24 in PfFtn (Fig. 1B) is essential for catalysis of Fe(II) oxidation 13. Subsequently, we measured the hyperfine effect of the 57Fe nucleus on this signal. Preparing the sample with 57Fe(II), I = 1/2, instead of NATFe(II) slightly broadened the g = 2.0031 signal at its shoulders. This small broadening effect is considerably less than that observed for the 57Fe hyperfine broadening in the g = 2.00 EPR signal of the [Fe(III)‐Fe(IV)] species (S = 1/2) in a synthetic complex 15 or that reported for [Fe(III)‐Fe(IV)] species in ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) 16, 17. The hyperfine effect of 57Fe on the S = 1/2 EPR signal in ferritin was also less than the hyperfine effect of 57Fe on the EPR signal of the proposed [Fe(III)‐Fe(IV)]‐Trp radical species in toluene/o‐xylene monooxygenase hydroxylase 18. Nevertheless, from the results of EPR spectroscopy it is not clear whether the slight effect of 57Fe on the EPR signal is due to a [Fe(III)‐Fe(III)]‐Tyr radical species or a [Fe(III)‐Fe(IV)]‐Tyr radical species in the ferroxidase center.

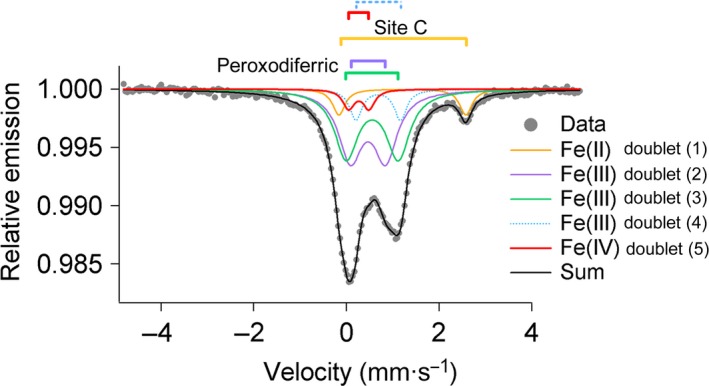

Mössbauer spectroscopy provides evidence for the presence of an Fe(IV) intermediate

The reaction of PfFtn with 48 Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer was quenched at 1.0 s. The reaction was quenched after 1.0 s, because at this time the absorbance of the intermediates in the ferroxidase center was close to their maximum (Fig. S1). This suggests that the amount of Fe(III) products, which might obscure the Mössbauer spectra of the intermediates of the reaction, is still negligible. Before the addition of dioxygen to ferritin containing 48 Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer, the percentages of 57Fe(II) in sites A, B, and C were 41%, 40%, and 19%, respectively (Table 1). According to the distribution model we explained previously 10 it could be concluded that in 32% of the subunits (~ 7 subunits per 24‐mer) sites A, B, and C were occupied with Fe(II) (AIIBIICII subunits). After 0.7 s all the Fe(II) in sites A and B was converted to the peroxodiferric species but the Fe(II) in site C was not oxidized (Table 1). One second after the addition of dioxygen simulation of the Mössbauer data required five doublets (Fig. 3, Table 1, and Fig. S5). Doublet 1 (orange trace) is a minor Fe(II) species (Table 1), which might be assigned to the unreacted Fe(II) in site C. Doublets 2 and 3 (purple and green trace) are two major Fe(III) species (each 39%) whose Mössbauer parameters (Table 1) are very similar to those typically reported for an iron pair with η2‐O2 bonding mode and consistent with those observed previously 19. These Mössbauer parameters specially suggest a μ‐η1‐η2 bonding mode as proposed previously for HuHF and PfFtn based on Mössbauer spectroscopy 10, or as suggested based on the results of X‐ray crystallography for Helicobacter pylori ferritin 12. We assign these doublets to the major peroxodiferric species in sites A and B of the ferroxidase center. The fourth doublet (9 ± 2%; light‐blue trace) has Mössbauer parameters of δ = 0.69 mm/s, ΔEQ = 0.97 mm/s (Table 1), which are close to those of high‐spin Fe(III) species (S = 5/2) reported for intermediate (X) in RNR (Table 2).

Table 1.

Iron species observed in PfFtn at different times points for addition of 48 Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer

| Time (s) | Doublet | Fe species | % of 57Fe(II) | Mössbauer parameters | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ (mm/s) | ΔEQ (mm/s) | |||||

| 0 | 1 | Fe(II) | 19(1) | 1.39 (1) | 3.27 (1) | 10 |

| 2 | Fe(II) | 41(2) | 1.38 (1) | 2.73 (2) | ||

| 3 | Fe(II) | 40(1) | 1.17 (1) | 2.54 (1) | ||

| 0.7 | 1 | Fe(II) | 16(2) | 1.20 (1) | 2.77 (1) | 10 |

| 2 | Fe(III)a | 42(1) | 0.49 (1) | 0.76 (1) | ||

| 3 | Fe(III)b | 42(1) | 0.56 (2) | 1.12 (1) | ||

| 1 | 1 | Fe(II) | 8(1) | 1.20 (1) | 2.77 (2) | This work |

| 2 | Fe(III)a | 39(1) | 0.46 (2) | 0.76 (1) | ||

| 3 | Fe(III)b | 39(1) | 0.56 (1) | 1.12 (1) | ||

| 4 | Fe(III) | 9(2) | 0.69 (1) | 0.97 (2) | ||

| 5 | Fe(IV) | 5(2) | 0.25 (2) | 0.46 (2) | ||

| 300 | 1 | Fe(III) | 42 | 0.49 (1) | 1.14 (1) | 10 |

| 2 | Fe(III) | 58 | 0.48 (1) | 0.67 (1) | ||

At time 0 no dioxygen was added. After the addition of dioxygen samples were rapidly frozen at 0.7, 1, and 300 s.

a,bThe Fe(III) doublets were assigned to the peroxodiferric intermediate in the ferroxidase center.

Figure 3.

Mössbauer spectroscopy provides evidence for the presence of an [Fe(III)‐Fe(IV)] species during catalysis of Fe(II) oxidation in subunits whose sites A, B, and C are occupied with Fe(II). Mössbauer spectrum was recorded for a sample quenched circa 1.0 s after aerobic addition of 48 57Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer (45 μm) to apo‐PfFtn. The black solid line (Sum) is the superposition of the simulated spectra. Measurements were performed at 80 K.

Table 2.

Comparison of the Mössbauer parameters of Fe(IV) species in ferritin with those reported for the Fe(IV) in model compounds or dioxygen‐activating enzymes. RNR (X), intermediate X in ribonucleotide reductase; Mc, Methylococcus capsulatus; Mt, Methylosinus trichosporium; ([H3buea]3−), tris[(N’‐tert‐butylureaylato)‐N‐ethylene]aminato

| Sample | Fe species | % of 57Fe(II) | Mössbauer parameters | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ (mm/s) | ΔEQ (mm/s) | ||||

| PfFtn | Fe(III) | 9(2) | 0.69 (1) | 0.97 (2) | This work |

| Fe(IV) | 5(2) | 0.25 (2) | 0.46 (2) | ||

| RNR (X) | Fe(III) | — | 0.56 (3) | −0.9 (1) | 20 |

| Fe(IV) | — | 0.26 (4) | −0.6 (1) | ||

| MMOH Q (Mc) | Fe(IV) | 0.21;0.14 | 0.68; 0.55 | 21 | |

| MMOH Q (Mt) | Fe(IV) | 0.17 | 0.53 | 22 | |

| [FeH3buea(O)]− | Fe(IV) | 0.02 | 0.43 | 23 | |

| [(H2O)5FeO]2+ | Fe(IV) | 0.38 (2) | 0.33 (2) | 24 | |

The numbers in parentheses show the error of the last digit. In PfFtn the signs of ΔEQ were not determined.

The fifth doublet (red trace) has Mössbauer parameters of δ = 0.25 mm/s, ΔEQ = 0.46 mm/s (Tables 1, 2), which are particularly close to those reported for Fe(IV) species (Table 2). In PfFtn the amount of Fe(IV) doublet was circa 5 ± 2% relative to the total amount of Fe(II) added). The amount of Fe(IV) (5 ± 2% of the total 57Fe(II) added), which we detected by Mössbauer spectroscopy, accounts for circa 30% of the subunits whose site C is occupied with Fe(II) (AIIBIICII subunits) 10, 13. Because for the addition of 48 Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer 7–8 subunits were in the AIIBIICII form 10, the Fe(IV) species was detected in ~ 2 subunits. We conclude that an Fe(III)‐Fe(IV) species was formed as a result of decay of the peroxodiferric species because: (a) no Fe(IV) was observed at 0.7 s when all of the Fe(II) in the ferroxidase center was converted to the peroxodiferric species (Table 1), (b) formation of Fe(IV) species in solution due to Fenton chemistry has been ruled out previously 24, (c) the Mössbauer parameters of the high‐spin Fe(III) and the Fe(IV) species are close to those reported for the Fe(III)‐Fe(IV) couple in RNR (Table 2), and (d) the sum of the amount of the high‐spin Fe(III) (9%) and the Fe(IV) (5%) species 1.0 s after the addition of dioxygen (doublets 4 and 5 in Table 1) is equal to the sum of the amount of Fe(II) oxidized in site C (8%) and the amount of Fe(III) species in the form of the peroxodiferric species disappeared (6%) from 0.7 s to 1 s after the addition of dioxygen (Table 1). Therefore, ~ 5% of the high‐spin Fe(III) species is coupled to Fe(IV) to form a Fe(III)‐Fe(IV) mixed‐valence species. The remaining 4% of Fe(III) species might be assigned to the Fe(III) product. It should be noted that since a model with five doubles was sufficient to obtain a good fit to the data (Fig. 3), the Mössbauer parameters of the remaining 4% Fe(III) assigned to the Fe(III) products are assumed to be the same as that of the Fe(III) in the Fe(III)‐Fe(IV) mixed valence.

Discussion

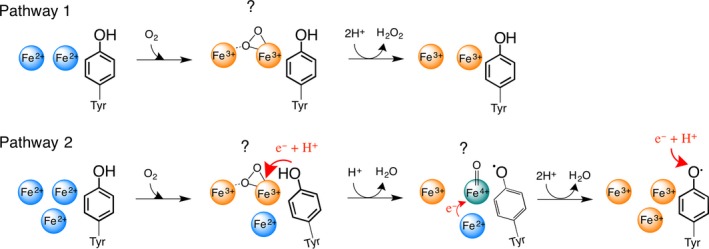

Our present data for PfFtn together with our previous Mössbauer 10 and EPR 13 studies of this protein provide evidence for the presence of an Fe(IV) intermediate and a tyrosine radical in the catalytic cycle of the ferroxidase center besides the peroxodiferric species. At 0.7 s all the iron in the ferroxidase center was in the form of the peroxodiferric species and the Fe(II) in site C was not oxidized (Table 1). At 1.0 s the amount of Fe(III) assigned to the peroxodiferric species decreased 6% compared to that at 0.7 s. Moreover, at 1.0 s the amount of Fe(II) in site C was ~ 8%, which is a decrease of 8% compared to that at 0.7 s. This decrease in the amount of the peroxodiferric and Fe(II) species from 0.7 to 1.0 s, which was about 14% of the Fe(II) initially added, is equivalent to the amount of Fe(III) and Fe(IV) species formed. The Mössbauer parameters of the Fe(III) and the Fe(IV) species (Table 2) are very similar to those reported for the Fe(III)‐Fe(IV) couple in RNR (Table 2). Based on these data, we propose a model for the role of Fe(IV) species in oxidation of Fe(II) substrate in site C (Fig. 4): when there is no extra Fe(II) near the ferroxidase center (AIIBIIC0 subunits), the peroxodiferric species decays to Fe(III) products and H2O2 is released (pathway 1, Fig. 4). In contrast when site C is occupied with Fe(II) substrate (AIIBIICII subunits), the conserved tyrosine provides an electron to the peroxodiferric intermediate and consequently a water molecule is formed and the peroxodiferric intermediate is rapidly converted to an [Fe(III)‐Fe(IV)]‐Tyr radical species (pathway 2, Fig. 4). This intermediate subsequently oxidizes the nearby Fe(II) substrate in site C to generate a second water molecule. This two‐step reduction of molecular oxygen prevents formation of highly reactive hydroxyl or superoxide radicals. Under reducing conditions the tyrosine radical might be reduced via an electron transfer mechanism from a yet to be identified partner and the addition of a proton or alternatively by an Fe(II) ion. The final Fe(III) products will stay metastably in the ferroxidase center and are displaced by incoming Fe(II) as demonstrated previously 2. The amount of the Fe(IV) species and the tyrosine radical intermediate under single turnover conditions, that is, addition of 48 Fe(II) per ferritin 24‐mer, was substoichiometric and consistent with their formation in AIIBIICII subunits (subunits in which sites A, B, and C were filled with Fe(II)). The reason why the Fe(IV) intermediate was apparently only formed in subunits whose site C was occupied with Fe(II) is not known. It is possible that binding of Fe(II) to site C induces conformational changes in the ferroxidase center and as a consequence, oxidation of the conserved tyrosine, which will be followed by the formation of the [Fe(III)‐Fe(IV)] species. This speculation is strengthened by the fact that the amino acid residues in the coordination environment of site C are directly linked to those in the coordination environment of sites A and B of the ferroxidase center (Fig. 1B), and conformational changes in amino acid residues of sites C and B have been observed 19. Moreover, consistent with this speculation is our previous Mössbauer study of PfFtn, in which we found that the Mössbauer parameters of Fe(II) in site C before the addition of dioxygen are different than those after the addition of dioxygen (Table 1) 10. The importance of site C for efficient catalysis of Fe(II) oxidation has been reported for other ferritins namely Escherichia coli ferritin A 25, 26 and Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough ferritin 27.

Figure 4.

The proposed model for the role of the high‐valent Fe(IV) intermediate in the catalysis of Fe(II) oxidation. In pathway 1, when there is no extra Fe(II) nearby the ferroxidase center (site C), the two Fe(II) ions in the ferroxidase center are oxidized via a peroxodiferric intermediate to form the product. The bonding mode of dioxygen in peroxodiferric intermediate is under debate. Recent data based on X‐ray crystallography and Mössbauer spectroscopy suggest a μ‐η1‐η2 bonding mode. In pathway two, when extra Fe(II) is present in the vicinity of the ferroxidase center, first the two Fe(II) ions in the ferroxidase center form the peroxodiferric species. A conformational change occurs due to the presence of Fe(II) at site C. Consequently, the peroxodiferric species rapidly decays as the highly conserved tyrosine provides an electron and a proton. As a result a water molecule and an Fe(IV) intermediate species is formed. The exact binding mode of oxygen in Fe(IV) species is not known (?) and in the picture a terminal oxo group is shown for simplicity. The high‐valent Fe(IV) species then rapidly oxidizes the extra Fe(II) nearby to form a second water molecule and the Fe(III) products. Under reducing conditions the tyrosine radical is possibly reduced by an electron from a yet to be identified redox partner followed by the addition of a proton.

The highest mid‐point potential for the first one‐electron reduction of the Fe(III)‐Fe(III) couple in the ferroxidase center is circa 200 mV 28, 29. An Fe(IV) species will have a more positive potential than this value and will be able to oxidize extra Fe(II) ions nearby the ferroxidase center, that is, Fe(II) in site C. The proposed model for catalysis of Fe(II) oxidation in site C by the [Fe(III)‐Fe(IV)] species in the ferroxidase center (pathway 2, Fig. 4) is consistent with our previous simulation of the progress curves of Fe(III) formation and those of the peroxodiferric intermediate 13, which predicted oxidation of Fe(II) in site C by the iron in the ferroxidase center. Moreover, our model is consistent with the reported increase in the stoichiometry of Fe(II) oxidized per dioxygen for microbial and eukaryotic ferritins upon increasing the amount of Fe(II) added per ferritin 24‐mer 13, 30. At Fe(II) per subunit ratios of more than 2, the occupancy of site C increases, thereby more Fe(II) at site C will be oxidized via the high‐valent Fe(IV) species in the ferroxidase center. As a result, the stoichiometry of Fe(II) oxidized per dioxygen molecule increases. Oxidation of Fe(II) via the [Fe(III)‐Fe(IV)] intermediate appears to be dependent on the affinity and coordination of site C and might be more efficient in ferritins whose site C has a higher affinity for Fe(II). Nevertheless, further investigation is required to test the hypothesis that an Fe(IV) species is formed in the ferroxidase center and to confirm its role in catalysis.

Author contributions

KHE conceived the study, performed the experiments, and analyzed data, WRH wrote the programs for SVD analysis and help with analysis, EB performed Mössbauer measurements and help with analysis of data, KHE wrote the manuscript with contribution from all the authors.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Materials and methods.

Fig. S1. UV‐visible absorbance spectrum of Fe(II) oxidation by PfFtn.

Fig. S2. EPR spectroscopy confirmed formation of a tyrosine radical near a metal center.

Fig. S3. A plot of the intensity of the g=2.0031 signal obtained using numerical double integration of the experimental derivative signal as a function of microwave power.

Fig. S4. A plot of the double integral (area) of the g=2.0031 signal as a function of inverse temperature.

Fig. S5. Different models were used to simulate the Mössbauer spectrum of 48 57Fe per PfFtn 24‐mer 1.0 s after addition of molecular oxygen.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an EMBO Long‐Term Fellowship to Kourosh H. Ebrahimi (ALTF 157‐2015). We thank Marc Strampraad for his assistance with freeze‐quench experiments.

Edited by Miguel De la Rosa

References

- 1. Ebrahimi KH, Hagedoorn P‐L and Hagen WR (2015) Unity in the biochemistry of the iron‐storage proteins ferritin and bacterioferritin. Chem Rev 115, 295–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ebrahimi KH, Bill E, Hagedoorn P‐L and Hagen WR (2012) The catalytic center of ferritin regulates iron storage via Fe (II)‐Fe (III) displacement. Nat Chem Biol 8, 941–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tinberg CE and Lippard SJ (2011) Dioxygen activation in soluble methane monooxygenase. Acc Chem Res 44, 280–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pereira AS, Small W, Krebs C, Tavares P, Edmondson DE, Theil EC and Huynh BH (1998) Direct spectroscopic and kinetic evidence for the involvement of a peroxodiferric intermediate during the ferroxidase reaction in fast ferritin mineralization. Biochemistry 37, 9871–9876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moënne‐Loccoz P, Krebs C, Herlihy K, Edmondson DE, Theil EC, Huynh BH and Loehr TM (1999) The ferroxidase reaction of ferritin reveals a diferric μ‐1, 2 bridging peroxide intermediate in common with other O2‐activating non‐heme diiron proteins. Biochemistry 38, 5290–5295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xue G, Wang D, De Hont R, Fiedler AT, Shan X, Münck E and Que L (2007) A synthetic precedent for the [FeIV2(μ‐O)2] diamond core proposed for methane monooxygenase intermediate Q. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104, 20713–20718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Banerjee R, Proshlyakov Y, Lipscomb JD and Proshlyakov DA (2015) Structure of the key species in the enzymatic oxidation of methane to methanol. Nature 518, 431–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hwang J, Krebs C, Huynh BH, Edmondson DE, Theil EC and Penner‐Hahn JE (2000) A short Fe‐Fe distance in peroxodiferric ferritin: control of Fe substrate versus cofactor decay? Science 287, 122–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schwartz JK, Liu XS, Tosha T, Theil EC and Solomon EI (2008) Spectroscopic definition of the ferroxidase site in m ferritin: comparison of binuclear substrate vs cofactor active sites. J Am Chem Soc 130, 9441–9450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ebrahimi KH, Bill E, Hagedoorn P‐L and Hagen WR (2016) Spectroscopic evidence for the role of a site of the di‐iron catalytic center of ferritins in tuning the kinetics of Fe(ii) oxidation. Mol BioSyst 12, 3576–3588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bou‐Abdallah F, Papaefthymiou G, Scheswohl D, Stanga S, Arosio P & Chasteen N (2002) μ‐1, 2‐Peroxobridged di‐iron (III) dimer formation in human H‐chain ferritin. Biochem J 364, 57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim S, Lee J‐H, Seok JH, Park Y‐H, Jung SW, Cho AE, Lee C, Chung MS and Kim KH (2016) Structural basis of novel iron‐uptake route and reaction intermediates in ferritins from gram‐negative bacteria. J Mol Biol 428, 5007–5018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ebrahimi KH, Hagedoorn PL and Hagen WR (2013) A conserved tyrosine in ferritin is a molecular capacitor. ChemBioChem 14, 1123–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ryle MJ, Liu A, Muthukumaran RB, Ho RY, Koehntop KD, McCracken J, Que L and Hausinger RP (2003) O2‐and α‐ketoglutarate‐dependent tyrosyl radical formation in TauD, an α‐keto acid‐dependent non‐heme iron dioxygenase. Biochemistry 42, 1854–1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dong Y, Que LJ, Kauffmann K and Münck E (1995) An exchange‐coupled complex with localized high‐spin FeIV and FeIII sites of relevance to cluster X of Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase. J Am Chem Soc 117, 11377–11378. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Voevodskaya N, Galander M, Högbom M, Stenmark P, McClarty G, Gräslund A & Lendzian F (2007) Structure of the high‐valent Fe III Fe IV state in ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) of Chlamydia trachomatis—Combined EPR, 57 Fe‐, 1 H‐ENDOR and X‐ray studies. Biochim Biophys Acta 1774, 1254–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Doan PE, Shanmugam M, Stubbe J and Hoffman BM (2015) Composition and structure of the inorganic core of relaxed intermediate X (Y122F) of Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase. J Am Chem Soc 137, 15558–15566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murray LJ, García‐Serres R, Naik S, Huynh BH and Lippard SJ (2006) Dioxygen activation at non‐heme diiron centers: characterization of intermediates in a mutant form of toluene/o‐xylene monooxygenase hydroxylase. J Am Chem Soc 128, 7458–7459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stillman T, Hempstead P, Artymiuk P, Andrews S, Hudson A, Treffry A, Guest J and Harrison P (2001) The high‐resolution X‐ray crystallographic structure of the ferritin (EcFtnA) of Escherichia coli; comparison with human H ferritin (HuHF) and the structures of the Fe 3 + and Zn 2 + derivatives. J Mol Biol 307, 587–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sturgeon BE, Burdi D, Chen S, Huynh B‐H, Edmondson DE, Stubbe J and Hoffman BM (1996) Reconsideration of X, the diiron intermediate formed during cofactor assembly in E. coli ribonucleotide reductase. J Am Chem Soc 118, 7551–7557. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu KE, Valentine AM, Wang D, Huynh BH, Edmondson DE, Salifoglou A and Lippard SJ (1995) Kinetic and spectroscopic characterization of intermediates and component interactions in reactions of methane monooxygenase from Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath). J Am Chem Soc 117, 10174–10185. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee SK, Fox BG, Froland WA, Lipscomb JD and Munck E (1993) A transient intermediate of the methane monooxygenase catalytic cycle containing an FeIVFeIV cluster. J Am Chem Soc 115, 6450–6451. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lacy DC, Gupta R, Stone KL, Greaves J, Ziller JW, Hendrich MP and Borovik A (2010) Formation, structure, and EPR detection of a high spin FeIV‐oxo species derived from either an FeIII‐oxo or FeIII‐OH complex. J Am Chem Soc 132, 12188–12190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pestovsky O, Stoian S, Bominaar EL, Shan X, Münck E, Que L and Bakac A (2005) Aqueous FeIV==O: spectroscopic Identification and Oxo‐Group Exchange. Angew Chem Int Ed 44, 6871–6874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bou‐Abdallah F, Yang H, Awomolo A, Cooper B, Woodhall M, Andrews S and Chasteen N (2014) Functionality of the three‐site ferroxidase center of escherichia coli bacterial ferritin (EcFtnA). Biochemistry 53, 483–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Treffry A, Zhao Z, Quail MA, Guest JR and Harrison PM (1998) How the presence of three iron binding sites affects the iron storage function of the ferritin (EcFtnA) of Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett 432, 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pereira AS, Timóteo CG, Guilherme M, Folgosa F, Naik SG, Duarte AG, Huynh BH and Tavares P (2012) Spectroscopic evidence for and characterization of a trinuclear ferroxidase center in bacterial ferritin from desulfovibrio vulgaris hildenborough. J Am Chem Soc 134, 10822–10832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tatur J and Hagen WR (2005) The dinuclear iron‐oxo ferroxidase center of Pyrococcus furiosus ferritin is a stable prosthetic group with unexpectedly high reduction potentials. FEBS Lett 579, 4729–4732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ebrahimi KH, Hagedoorn P‐L and Hagen WR (2013) Phosphate accelerates displacement of Fe(III) by Fe(II) in the ferroxidase center of Pyrococcus furiosus ferritin. FEBS Lett 587, 220–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xu B and Chasteen N (1991) Iron oxidation chemistry in ferritin. Increasing Fe/O2 stoichiometry during core formation. J Biol Chem 266, 19965–19970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Materials and methods.

Fig. S1. UV‐visible absorbance spectrum of Fe(II) oxidation by PfFtn.

Fig. S2. EPR spectroscopy confirmed formation of a tyrosine radical near a metal center.

Fig. S3. A plot of the intensity of the g=2.0031 signal obtained using numerical double integration of the experimental derivative signal as a function of microwave power.

Fig. S4. A plot of the double integral (area) of the g=2.0031 signal as a function of inverse temperature.

Fig. S5. Different models were used to simulate the Mössbauer spectrum of 48 57Fe per PfFtn 24‐mer 1.0 s after addition of molecular oxygen.