Abstract

Variation in FOXC1 and PITX2 is associated with Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome, characterised by structural defects of the anterior chamber of the eye and a range of systemic features. Approximately half of all affected individuals will develop glaucoma, but the age at diagnosis and the phenotypic spectrum have not been well defined. As phenotypic heterogeneity is common, we aimed to delineate the age-related penetrance and the full phenotypic spectrum of glaucoma in FOXC1 or PITX2 carriers recruited through a national disease registry. All coding exons of FOXC1 and PITX2 were directly sequenced and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification was performed to detect copy number variation. The cohort included 53 individuals from 24 families with disease-associated FOXC1 or PITX2 variants, including one individual diagnosed with primary congenital glaucoma and five with primary open-angle glaucoma. The overall prevalence of glaucoma was 58.5% and was similar for both genes (53.3% for FOXC1 vs 60.9% for PITX2, P=0.59), however, the median age at glaucoma diagnosis was significantly lower in FOXC1 (6.0±13.0 years) compared with PITX2 carriers (18.0±10.6 years, P=0.04). The penetrance at 10 years old was significantly lower in PITX2 than FOXC1 carriers (13.0% vs 42.9%, P=0.03) but became comparable at 25 years old (71.4% vs 57.7%, P=0.38). These findings have important implications for the genetic counselling of families affected by Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome, and also suggest that FOXC1 and PITX2 contribute to the genetic architecture of primary glaucoma subtypes.

Introduction

Anterior segment dysgenesis is a heterogeneous group of developmental disorders affecting the anterior structures of the eye.1 Axenfeld-Rieger malformation (ARM) represents a subgroup of anterior segment dysgenesis and refers to congenital ocular features including abnormal angle tissue, iris stromal hypoplasia, pseudopolycoria (additional pupillary opening in the iris), corectopia (displaced pupil), posterior embryotoxon (thickened and centrally displaced Schwalbe’s line) and/or peripheral anterior synechiae (irido-corneal adhesions).2, 3 A range of systemic features can also be present as part of the Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome (ARS), with the most common including facial dysmorphism, dental anomalies, periumbilical skin, cardiac defects and hearing loss.3, 4 The presence of anomalies in the anterior chamber angle and drainage structures of the eye contribute to a lifetime risk of developing glaucoma and can lead to irreversible blindness,5 although the severity of the anomalies does not seem to correlate well with the age at diagnosis, the severity or the progression of glaucoma.5 It is usually reported that ~50% of individuals with ARM will develop glaucoma, with an age of onset ranging from birth to late in adulthood.5 Guidelines for appropriate follow-up strategies for affected individuals without glaucoma lack a clear evidence base.

ARS is genetically heterogeneous. Deleterious sequence variants in the FOXC1 (6p25.3, MIM 601090)6, 7 and PITX2 genes (4q25, MIM 601542),8 as well as two additional loci (RIEG2 at 13q14 and 16q24),9, 10 have been associated with ARS. In addition, several copy number variants and chromosomal rearrangements disrupting FOXC1 or PITX2 have been reported in association with ARS.11, 12, 13, 14 Deleterious variants in both genes account for approximately 40% of individuals with ARS,11, 15 with inter- and intra-familial variable expressivity frequently reported.16, 17 Although the ARM ocular phenotype associated with variants in FOXC1 and PIXT2 is thought to be highly penetrant and undistinguishable between both genes, there is a variable expressivity of systemic features. Variants in PITX2 are more often associated with dental and/or umbilical anomalies, whereas individuals with FOXC1 variants often have the ARM phenotype alone, or display a range of other systemic anomalies including heart anomalies, hearing defects, developmental delay and/or growth delay.11, 15, 18 In addition, FOXC1 has recently been identified as a primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) susceptibility locus19 and an essential regulator of lymphangiogenesis.20

FOXC1 encodes a forkhead transcription factor encoded by a single exon, whereas PITX2 is a member of a paired class of homeodomain transcription factors and encodes four alternative transcripts (PITX2A, B, C and D). Both are expressed during embryonic development and regulate downstream genes important for cell differentiation and migration via DNA binding. FOXC1 and PITX2 are co-expressed in the periocular mesenchyme and can physically interact with each other via their C-terminal domain and their homeobox domain, respectively.21 PITX2 can inhibit the transactivation activity of FOXC1, which is lost in the presence of PITX2 loss-of-function variants.21 The transcriptional activity of both genes requires tight regulation during embryogenesis for proper development of anterior segment tissues.

Although the morphological ocular anomalies associated with FOXC1 and PITX2 variants have been well described, the spectrum and prevalence of glaucoma in mutation carriers have not been well characterised. In this study, we delineated the glaucoma prevalence and phenotype in a cohort of patients diagnosed with ARM and their family members with FOXC1 and PITX2 variants.

Methods

Participants’ recruitment

Ethics approval was obtained from the Southern Adelaide Clinical Human Research Ethics Committee. The study was conducted in accordance with the revised Declaration of Helsinki. Individuals were recruited through the Australian and New Zealand Registry of Advanced Glaucoma (ANZRAG) as described previously.22 Informed written consent and a blood or saliva sample for DNA extraction purposes were obtained. Clinical information was collected by the patient’s usual treating ophthalmologist. The feedback of results and genetic counselling was provided to the participants.

Individuals with ARM recruited in the ANZRAG were tested for the FOXC1 and PITX2 genes. Family members of individuals with variants in these genes were offered genetic testing. The cohort included all ARM probands and their family members identified as having a deleterious variant in the FOXC1 or the PITX2 genes. The diagnoses of ARM and glaucoma were made by the treating specialist who referred the patient to the ANZRAG. Individuals with ARM were recruited in the ANZRAG regardless of their glaucoma status. Advanced glaucoma was defined as visual field loss in the worse eye related to glaucoma with at least two out of the four central fixation squares having a pattern standard deviation <0.5% on a reliable Humphrey 24-2 field, or a mean deviation of <−22 dB. Ocular hypertension was defined by an intraocular pressure ⩾21 mm Hg.

Genetic testing

FOXC1 and PITX2 genetic testing was performed through the NATA (National Association of Testing Authorities) accredited laboratories of SA Pathology at the Flinders Medical Centre (Bedford Park, SA, Australia). Venous blood specimens were collected into EDTA tubes; genomic DNA was prepared from a 200 μl sample of blood and extracted by a QIAcube automated system using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit (Qiagen, Chadstone, VIC, Australia) reagents according to the manufacturer protocols. Saliva specimen were collected into an Oragene•DNA Self-Collection Kit (DNA Genotek Inc., Ottawa, ON, Canada) and the DNA was isolated from 500 μl of sample and extracted as described in the manufacturer’s instructions. The entire coding sequence and intron exon boundaries of FOXC1 and PITX2 were amplified as overlapping fragments in separate reactions with primer pairs (Supplementary Table 1).

Each polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was prepared using 100 ng of purified genomic DNA as template, 0.5 μm of each primer and a 1 × concentration of AmpliTaq Gold 360 Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Scoresby, VIC, Australia); 2.5 μl of 360 GC Enhancer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to each PITX2 reaction mix, and 5 μl to each FOXC1 reaction mix. All reactions were adjusted to a final volume of 25 μl with deionised water. Gene template targets were amplified in a Veriti thermal cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using separate conditions for each gene; FOXC1: Step 1, 95 °C for 10 min; Step 2, 95°C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s, repeated for 40 cycles; Step 3, 72 °C for 7 min. PITX2: Step 1, 94 °C for 5 min; Step 2, 94 °C for 30 s, 61 °C for 30 s (decreasing after five cycles by 1 °C every five cycles), 72 °C for 1 min, repeated for 15 cycles; Step 3, 94 °C for 30 sec, 58 °C for 50 s, 72 °C for 1 min, repeated for 35 cycles; Step 4, 72 °C for 10 min.

PCR amplified products were prepared for DNA sequencing by the 'ExoSAP' method using a 10 μl sample of each PCR reaction treated with 5 U of Exonuclease I (Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and 1 U of shrimp alkaline phosphatase (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH, USA) to remove residual primers and dNTPs. Bi-directional BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing (Thermo Fisher Scientific) reactions of the appropriate template and FOXC1 and PITX2 PCR primers were resolved and base called on an Applied Biosystems 3130xl Genetic Analyser (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Detection of sequence variants was performed with the aid of the Mutation Surveyor v4.0 (SoftGenetics LLC, State College, PA, USA) programme; all forward and reverse sequence trace files were assembled by the programme against the FOXC1 (NM_001453.2) and PITX2 (NM_153427.2) GenBank reference. Significant differences in the relative peak heights of the sequence traces observed between that of the patient sample and a normal control were automatically called as a sequence variant by Mutation Surveyor; all such calls were visually inspected for confirmation. The Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant (SIFT; http://sift.jcvi.org) and PolyPhen-2 HumVar (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2) software programmes were used to predict the potential impact of amino acid substitutions on the protein. Homologene (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/homologene) was used to assess the conservation among mammalian species. Allelic frequencies were compared with the population frequencies from the Exome Variant Server (EVS, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS) and the Exome Aggregation Consortium v0.3.1 (ExAC, http://exac.broadinstitute.org). All variants are publically available at the ClinVar database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/; accession numbers SCV000494251-SCV000494276).

FOXC1 and PITX2 were analysed for copy number variation by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) using the SALSA MLPA P054-B2 FOXL2-TWIST1 probemix (MRC Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The copy number present in the original DNA specimen was determined from the relative amplitude of each amplicon product detected using the ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer, and the data analysed using Peak Scanner v2.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Breakpoints of the genomic deletions and duplications that have been further characterised in Clinical Genetics using SNP arrays have been added in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Summary of FOXC1 variants identified and associated phenotype.

| ID | Age | Sex | Genomic location (NC_000006.12, hg38) | Nucleotide change (NM_001453.2) | Amino acid change (NP_001444.2) | Ocular features | Systemic features | Glc | Age glc dx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | 70 | M | g.1610545_1610554del | c.100_109del10 | p.(Gly34ThrfsTer8) | PAS, PE | Nil | Yes | 3 |

| 1B | 41 | F | g.1610545_1610554del | c.100_109del10 | p.(Gly34ThrfsTer8) | Haab’s striae, mild PAS | Nil | Yes | 4 |

| 2A | 25 | M | g.1610561_1610568del | c.116_123del8 | p.(Ala39GlyfsTer41) | PE, IH, corectopia | Nil | No | — |

| 2B | 34 | M | g.1610561_1610568del | c.116_123del8 | p.(Ala39GlyfsTer41) | IH, PE, PAS, corectopia | Nil | No | — |

| 3A | 37 | M | g.1610701C>T | c.256C>T | p.(Leu86Phe) | Corectopia | Nil | Yes | 33 |

| 3B | 6 | F | g.1610701C>T | c.256C>T | p.(Leu86Phe) | Corectopia | Nil | OHT | 5 |

| 4 | 56 | F | g.1610713G>A | c.268G>A | p.(Ala90Thr) | PE, PAS, ectropion uvea | Nil | Yes | 33 |

| 5A | 41 | F | g.1610761C>T | c.316C>T | p.(Gln106Ter) | IH, corectopia, Haab’s striae | Nil | No | — |

| 5B | 13 | F | g.1610761C>T | c.316C>T | p.(Gln106Ter) | PE, PAS | Pulmonary stenosis | No | — |

| 5C | 42 | M | g.1610761C>T | c.316C>T | p.(Gln106Ter) | IH, PE, PAS | Nil | Yes | 37 |

| 5D | 10 | F | g.1610761C>T | c.316C>T | p.(Gln106Ter) | PE, PAS | Nil | OHT | 6 |

| 6A | 37 | F | g.1610902A>C | c.457A>C | p.(Thr153Pro) | Haab’s striae, mild corectopia, cataracts | Short stature | Yes | 0 |

| 6B | 54 | F | g.1610902A>C | c.457A>C | p.(Thr153Pro) | PE, very mild PAS | Hearing Loss | Yes | 12 |

| 6C | 4 | M | g.1610902A>C | c.457A>C | p.(Thr153Pro) | Corneal haze, PE, mild corectopia | Nil | No | — |

| 6D | 17 | F | g.1610902A>C | c.457A>C | p.(Thr153Pro) | PE, PAS, mild corectopia | Intellectual disability, heart defect, hearing Loss, short stature, hydrocephalus | No | — |

| 7 | 26 | F | g.1611044_1611062del | c.599_617del19 | p.(Gln200ArgfsTer109) | PE, PAS, corneal oedema, ectropion uveae | Nil | Yes | 0 |

| 8A | 1 | M | g.1611111_1611126del | c.666_681del16 | p.(Ile223ProfsTer87) | PE | Heart defect | Yes | 0 |

| 8B | 28 | M | g.1611111_1611126del | c.666_681del16 | p.(Ile223ProfsTer87) | NA | Nil | Yes | 8 |

| 9A | 46 | M | g.1611370_1611394del | c.925_949del25 | p.(Ser309CysfsTer84) | Corectopia, pseudopolycoria, ectropion uveae, Haab’s striae | Nil | Yes | 1 |

| 9B | 44 | M | g.1611370_1611394del | c.925_949del25 | p.(Ser309CysfsTer84) | PE, IH, corectopia | Nil | No | — |

| 9C | 69 | F | g.1611370_1611394del | c.925_949del25 | p.(Ser309CysfsTer84) | PE, amblyopia | Club foot | No | — |

| 9D | 76 | M | g.1611370_1611394del | c.925_949del25 | p.(Ser309CysfsTer84) | IH, ectropion uveae | Club foot | No | — |

| 9E | 50 | F | g.1611370_1611394del | c.925_949del25 | p.(Ser309CysfsTer84) | NA | Nil | No | — |

| 10A | 29 | M | g.1611710C>A | c.1265C>A | p.(Ser422Ter) | PE, corectopia, megalocornea | Nil | OHT | 2 |

| 10B | 33 | M | g.1611710C>A | c.1265C>A | p.(Ser422Ter) | NA | Nil | Yes | 8 |

| 11A | 41 | F | g.1611936C>G | c.1491C>G | p.(Tyr497Ter) | Mild PAS, PE | Hearing Loss | Yes | 15 |

| 11B | 6 | M | g.1611936C>G | c.1491C>G | p.(Tyr497Ter) | PE, PAS | Nil | No | — |

| 12 | 7 | F | g.(?_165632)_(3549058_35532219)del | c.(?_-1)_(*1_?)del | — | PE, PAS, corectopia | Fine motor skills delay | Yes | 2 |

| 13A | 43 | M | g.?_?insNC_000006.12:g.(947938_951144)_(1832702_1833922)dup | c.(?_-1)_(*1_?)dup | — | PAS | Nil | Yes | 18 |

| 13B | 64 | F | g.?_?insNC_000006.12:g.(947938_951144)_(1832702_1833922)dup | c.(?_-1)_(*1_?)dup | — | Nil | Nil | Yes | 34 |

Abbreviations: Glc, glaucoma; IH, iris stromal hypoplasia; OHT, ocular hypertension; PAS, peripheral anterior synechiae; PE, posterior embryotoxon; NA, not available.

Table 2. Summary of PITX2 variants identified and associated phenotype.

| ID | Age | Sex | Genomic location (NC_000004.12, hg38) | Nucleotide change (NM_153427.2) | Amino acid change (NP_00316.2) | Ocular features | Systemic features | Glc | Age glc/ OHT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14A | 38 | M | g.110621211_110621232del | c.184_205del22 | p.(Arg62AlafsTer86) | Corectopia | Dental, periumbilical skin, WPW syndrome | Yes | 14 |

| 14B | 66 | F | g.110621211_110621232del | c.184_205del22 | p.(Arg62AlafsTer86) | PAS, IH | Dental, periumbilical skin | Yes | 12 |

| 15A | 82 | M | g.110621225G>A | c.191C>T | p.(Pro64Leu) | Nil | Dental, periumbilical skin | Yes | 48 |

| 15B | 55 | F | g.110621225G>A | c.191C>T | p.(Pro64Leu) | IH, PE, PAS | Dental, umbilical hernia | Yes | 25 |

| 15C | 42 | M | g.110621225G>A | c.191C>T | p.(Pro64Leu) | Mild IH | Dental, periumbilical skin | OHT | 20 |

| 15D | 20 | F | g.110621225G>A | c.191C>T | p.(Pro64Leu) | IH, PE | Dental, periumbilical skin | OHT | 18 |

| 16 | 42 | M | g.110621163C>T | c.252+1G>A | — | IH | Dental, umbilical hernia | Yes | 20 |

| 17A | 20 | M | g.110618670G>C | c.271C>G | p.(Arg91Gly) | PE, PAS, pseudopolycoria | Dental, periumbilical skin | Yes | 9 |

| 17B | 70 | M | g.110618670G>C | c.271C>G | p.(Arg91Gly) | PAS, pseudopolycoria, corectopia | Dental, umbilical hernia, absent left vas deferens | Yes | 28 |

| 17C | 26 | F | g.110618670G>C | c.271C>G | p.(Arg91Gly) | PE, PAS, corectopia | Dental, periumbilical skin | Yes | 26 |

| 18A | 49 | F | g.110618667C>G | c.274G>C | p.(Ala92Pro) | Corectopia, pseudopolycoria, PAS | Dental, periumbilical skin, epilepsy | Yes | 19 |

| 18B | 22 | F | g.110618667C>G | c.274G>C | p.(Ala92Pro) | Corectopia, pseudopolycoria, PAS, PE, IH | Dental, umbilical hernia | Yes | 21 |

| 18C | 16 | F | g.110618667C>G | c.274G>C | p.(Ala92Pro) | Peters, PAS, IH, cataract | Dental, umbilical hernia | OHT | 15 |

| 19 | 7 | M | g.110618315_110618316del | c.487_488delTC | p.(Ser163HisfsTer35) | Rieger anomaly | Dental, periumbilical skin, cleft palate | Yes | 1 |

| 20A | 59 | F | g.110618365_110618386del | c.555_576del22 | p.(Thr186SerfsTer4) | IH, PE | Dental, periumbilical skin | Yes | 26 |

| 20B | 37 | F | g.110618365_110618386del | c.555_576del22 | p.(Thr186SerfsTer4) | IH, PAS, PE | Dental, periumbilical skin | No | — |

| 21A | 24 | M | g.110618293A>T | c.648T>A | p.(Cys216Ter) | PAS, PE, IH, ectropion uvea, pseudopolycoria | Dental, periumbilical skin | Yes | 3 |

| 21B | 18 | F | g.110618293A>T | c.648T>A | p.(Cys216Ter) | PE | Dental, periumbilical skin | No | — |

| 22A | 45 | F | g.(?_110618049)_(110622472_?)del | c.(?_47-1103)_(*76_?)del | — | PE, PAS, IH | Dental, periumbilical skin | No | — |

| 22B | 20 | M | g.(?_110618049)_(110622472_?)del | c.(?_47-1103)_(*76_?)del | — | PE, IH, corectopia, pseudopolycoria | Dental, periumbilical skin, fine motor skills delay | No | — |

| 22C | 17 | F | g.(?_110618049)_(110622472_?)del | c.(?_47-1103)_(*76_?)del | — | PE, IH | Dental, periumbilical skin, imperforate anus | OHT | 17 |

| 23 | 36 | M | g.(111426357_111528916)_(111888401_111990971)del | c.(?_47-1103)_(*76_?)del | — | PAS, corectopia, pseudopolycoria | Dental, umbilical hernia | Yes | 13 |

| 24 | 28 | F | g.(?_110618124)_(110632999_?)del | c.(?_1)_(*1_?)del | — | PE, PAS, IH, corectopia | Dental, periumbilical skin, epilepsy | OHT | 6 |

Abbreviations: Glc, glaucoma; IH, iris stromal hypoplasia; OHT, ocular hypertension; PAS, peripheral anterior synechiae; PE, posterior embryotoxon; WPW, Wolff–Parkinson–White.

Statistical analysis

PASW Statistics, Rel. 18.0.1.2009 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analyses. Data are presented as median±standard deviation. Fisher’s exact test and Mann–Whitney U-test were used for the assessment of differences in non-parametric data.

Results

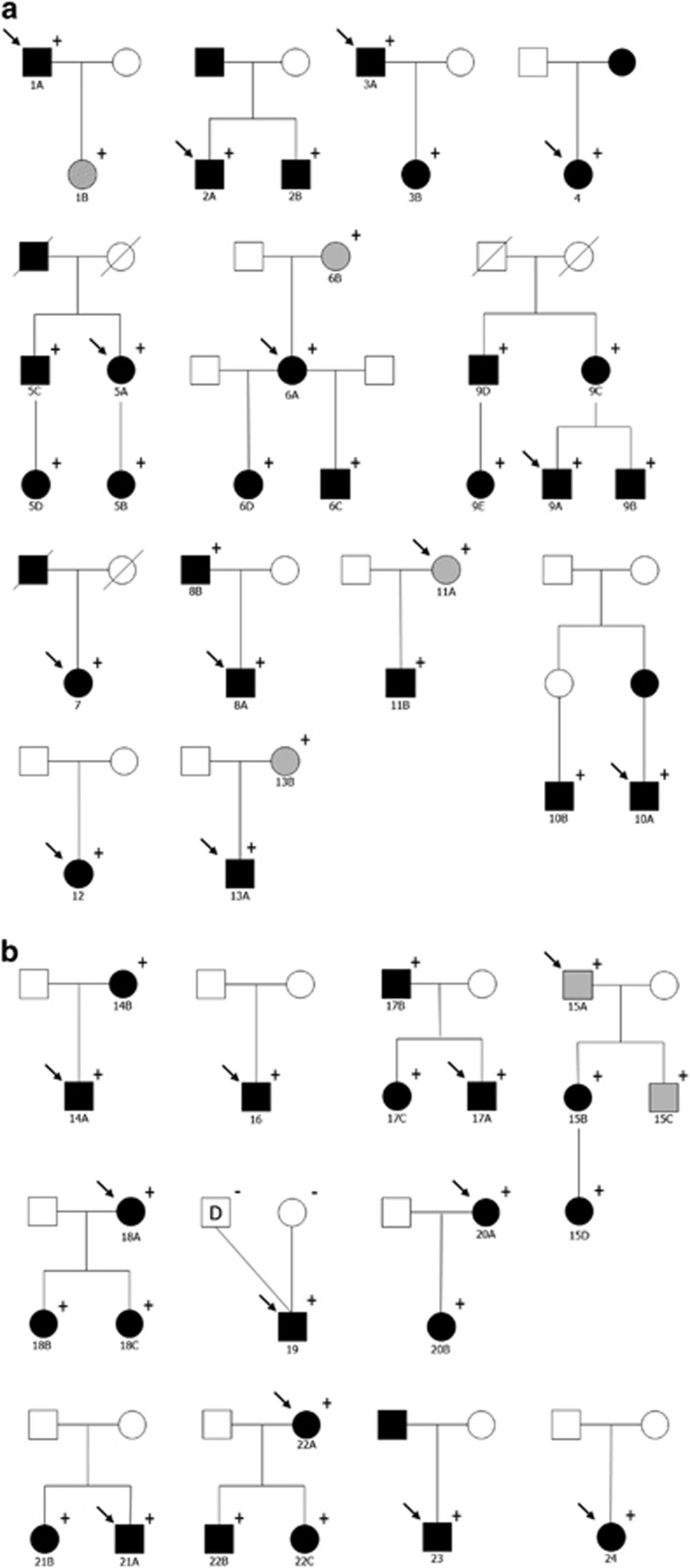

The cohort consisted of 53 individuals from 24 families with heterozygous FOXC1 or PITX2 variants. The pedigrees are depicted in Figure 1. There were 25 males (47.2%) and 28 females (52.8%). The majority were Caucasian (94.3%). The mean age of the participants was 35.7±20.4 years. Twenty probands (83%) had a family history of ARM and/or glaucoma.

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of the families. Round symbols indicate females; square symbols, males; black symbols, Axenfeld-Rieger Syndrome; grey symbols; primary open-angle glaucoma, dashed symbols; primary congenital glaucoma, unfilled symbols, unaffected; diagonal line, deceased; arrow, proband; D, sperm donor; +/−, presence/absence of the gene variant. (a) Families with FOXC1 variants. (b) Families with PITX2 variants.

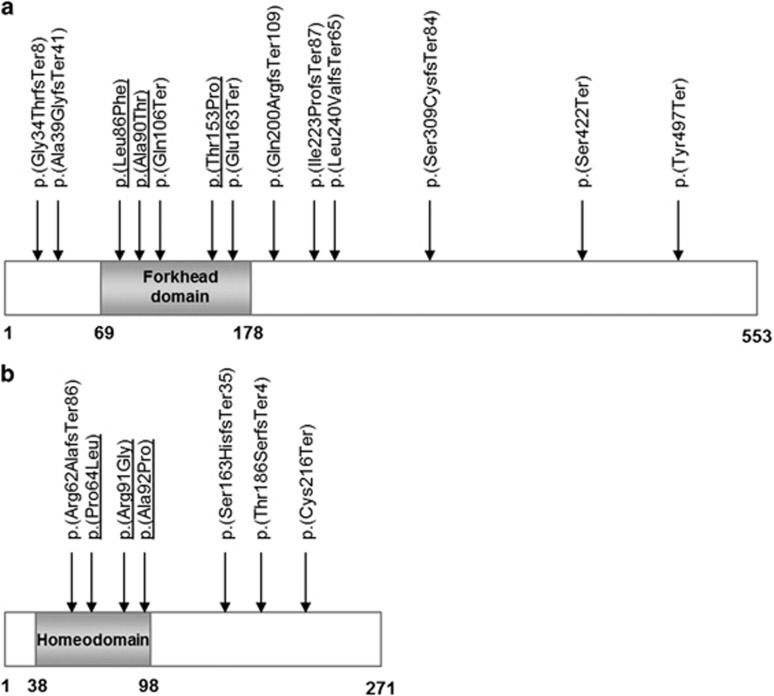

FOXC1 variants were present in 30 individuals (56.6%) compared with 23 (43.4%) in PITX2. We identified 19 sequence variants across both genes (Tables 1 and 2 and Figure 2), of which 15 were considered novel (not reported in the literature and not present in the EVS or the ExAC database). Four nonsense, eight frameshift and one splice site sequence variants were considered to affect function. Among six missense sequence variants identified, PITX2 p.(Pro64Leu) has previously been reported among different families as deleterious.23, 24, 25, 26 The other five missense sequence variants have not been reported before and were absent from the EVS and the ExAC database. Sequence variants p.(Leu86Phe), p.(Ala90Thr) and p.(Thr153Pro) are located in the forkhead domain of the FOXC1 gene which is important for DNA binding. Both Polyphen-2 and SIFT predicted these sequence variants to be damaging to the protein, with all three residues highly conserved across different species (Supplementary Figure 1). Similarly, PITX2 variants p.(Arg91Gly) and p.(Ala92Pro) are located in the homeobox domain, which is essential for binding to FOXC1,21 with both residues highly conserved across different species (Supplementary Figure 1) and predicted deleterious by Polyphen-2 and SIFT algorithms. As a result, these five missense variants were also considered likely to be disease-causing. Finally, we identified five copy number variants: one deletion and one duplication of the FOXC1 gene, and three deletions of the PITX2 gene. All encompassed the entire gene, apart from one PITX2 deletion, which spanned the last two coding exons.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the identified variants in the FOXC1 (a) and PITX2 proteins (b). Missense variants are underlined.

In this cohort, 31 individuals (58.5%) had glaucoma, 6 (11.3%) had ocular hypertension and 16 (30.2%) showed no sign of glaucoma (Tables 1 and 2 and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). Among the individuals with glaucoma, 48.4% (15/31) had advanced glaucoma as defined by the ANZRAG visual field criteria. The prevalence of glaucoma did not differ between FOXC1 (16/30, 53.3%) and PITX2 carriers (14/23, 60.9%, P=0.59), with the median age of glaucoma diagnosis at 13.5±12.2 years (range 0–48 years) for the entire cohort. Median age at diagnosis was significantly lower in FOXC1 compared with PITX2 carriers (6.0±13.0 years (range 0–37) vs 18.0±10.6 years (range 1–48), P=0.04). The penetrance at 10 years of age was 29.4% for the whole cohort and was significantly higher for FOXC1 carriers (42.9%) than PITX2 carriers (13.0%, P=0.03). Penetrance at 25 years was 63.8% for the whole cohort and was similar between both genes (57.7% for FOXC1 carriers vs 71.4% for PITX2 carriers, P=0.38). The median age of individuals who did not have glaucoma was 29.5±21.2 years (range 5–77 years) and was not significantly different between FOXC1 (34.0±24.2 years, range 5–77) and PITX2 carriers (20.0±13.1 years, range 17–46, P=0.74).

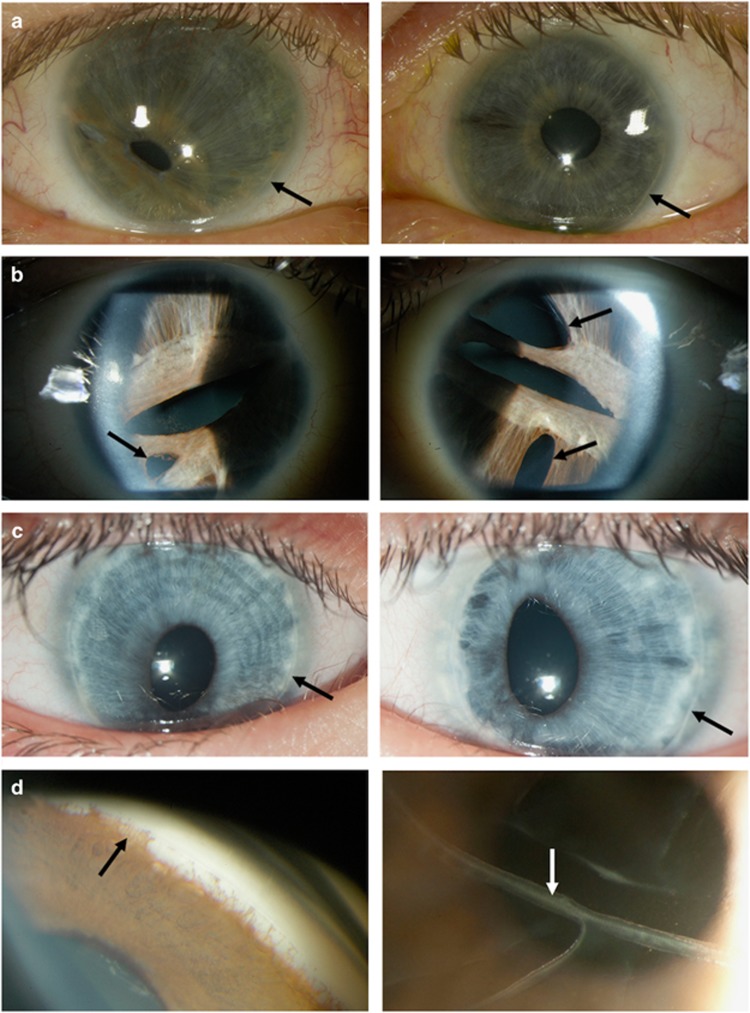

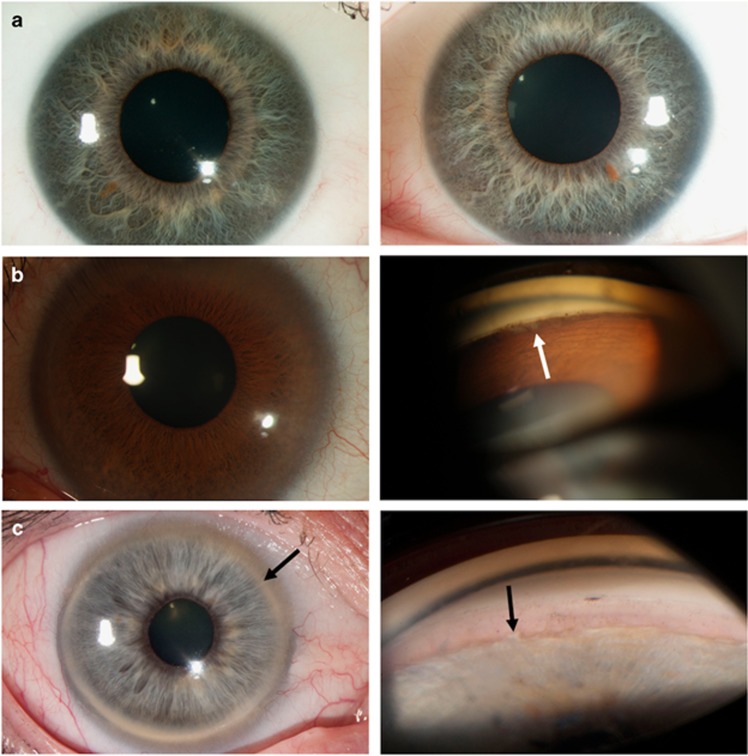

As shown in Tables 1 and 2, there was inter- and intra-familial phenotypic variability in ocular morphology and glaucoma type, although glaucoma prevalence was not different between loss-of-function variants, missense variants and copy number variants (P=0.72). Among the 53 individuals included in this study, 47 (88.7%) had classic ocular features of ARM (Figure 3). One family member of an individual with ARM was diagnosed with primary congenital glaucoma (PCG) and had mild features of ARM on re-examination after genetic testing (1B). Five family members of individuals with ARM had been diagnosed with POAG and had only mild or no features of ARM on re-examination after genetic testing (Figure 4). Four of the POAG cases had systemic features consistent with ASD, three carried FOXC1 variants (11A, 6B, 13B) and two had PITX2 variants (15A, 15C).

Figure 3.

Clinical photographs of individuals with ocular features of Axenfeld-Rieger Malformation. Photographs in (a–c) showing the right eye (left panel) and the left eye (right panel). (a) Slit lamp photos showing corectopia in the left panel, iris stromal hypoplasia in both eyes and posterior embryotoxon (black arrows) in both eyes (individual 9B). (b) Slit lamp photos showing corectopia, pseudopolycoria (black arrows) and iris stromal hypoplasia in both eyes (individual 18B). (c) Slit lamp photos showing corectopia and posterior embryotoxon (black arrows) in both eyes (individual 12). (d) Gonioscopy showing irido-corneal adhesions (black arrow, left panel) and photo showing the presence of breaks in the Descemet’s membrane (Haab’s striae, white arrow, right panel; individual 5A).

Figure 4.

Clinical photographs of individuals with glaucoma and no or mild ocular features of Axenfeld-Rieger malformation after re-examination. Photographs in a showing the right eye (left panel) and the left eye (right panel). (a) Slit lamp photos showing iris stromal hypoplasia and diffuse posterior embryotoxon in both eyes (individual 15D). (b) Slit lamp photo showing the absence of iris anomalies and diffuse posterior embryotoxon in the left panel and gonioscopy showing mild irido-corneal adhesions (white arrow) in the right panel (individual 11A). (c) Slit lamp photo showing posterior embryotoxon (black arrow) in the left panel and gonioscopy showing mild irido-corneal adhesions (black arrow) in the right panel (individual 6B).

All individuals with PITX2 variants had dental and umbilical anomalies including microdontia, hypodontia, redundant periumbilical skin or umbilical hernia. Additional systemic features were present in seven individuals and included Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome, cleft palate, imperforate anus, fine motor skill delay, unilateral vas deferens and epilepsy. In comparison with PITX2, the majority of FOXC1 carriers (21/30, 70.0%, P<0.001) had no systemic features. Among the FOXC1 carriers who did have systemic features, a range of abnormalities were reported including hearing loss (3/30, 10.0%), heart anomalies (3/30, 10.0%), short stature (2/30, 6.7%), club foot (2/30, 6.7%), hydrocephalus (1/30, 3.3%), intellectual disability (1/30, 3.3%) and fine motor skills delay (1/30, 3.3%).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the clinical phenotype of 53 ARM probands and their family members with variants in FOXC1 or PITX2. Glaucoma was present in 59% and ocular hypertension in an additional 11%. Shields5 reported glaucoma in 58% of individuals with a purely clinical diagnosis of ARM (with or without systemic features), and glaucoma prevalence among ARS patients with FOXC1 or PITX2 variants has previously been estimated at between 35% and 75%.11, 15, 18 This is the first study to investigate the age-related glaucoma prevalence of each gene, along with the associated glaucoma phenotype.

We found a similar prevalence of glaucoma between FOXC1 and PITX2 carriers. Previous studies found a higher prevalence of glaucoma among FOXC1 carriers than for PITX2 carriers.11, 15, 18 These differences can be explained by the age at diagnosis of affected individuals and the age of unaffected carriers reported. Although we have identified similar rates of glaucoma between both genes, the median age at diagnosis was significantly younger for FOXC1 carriers than for PITX2 carriers. Moreover, the prevalence at 25 years old was similar between both genes but the prevalence at 10 years old was significantly higher for FOXC1 carriers than for PITX2 carriers. Our results suggest that young unaffected individuals can still develop glaucoma at a later age. As a result, previous studies that were skewed toward PITX2 carriers15 or had young unaffected individuals11, 15 had a lower glaucoma prevalence than studies including a high proportion of FOXC1 carriers.18 Our findings showed that although the prevalence of glaucoma is similar between both genes, patients with FOXC1 variants are likely to develop glaucoma at a younger age than PITX2 carriers. In addition, our cohort included all available family members who were found to carry the suspected deleterious variant, which reduced the risk of recruitment bias.

In our study, one individual was initially diagnosed as PCG and five as POAG by their referring ophthalmologist. On re-examination, the individual with PCG and two individuals diagnosed with POAG had mild irido-corneal adhesions, whereas one individual with POAG had mild iris stromal hypoplasia. Two of the four FOXC1 carriers had hearing loss and the other two PITX2 carriers had dental and/or umbilical anomalies, none of which had been recorded before the molecular diagnosis. Individuals with variants in FOXC1 or PITX2 but without ocular features of ARS have been reported before,15, 27, 28 and in some individuals ARM can be so mild that it results in a clinical diagnosis of PCG or POAG. The variable expressivity associated with FOXC1 and PITX2 variants can make clinical diagnosis of ARS challenging, especially in the absence of ARM. However, all individuals were part of families with ARM and four out of six had systemic features consistent with ARS, emphasising the importance of delineating the systemic features associated with each gene to assist clinicians in reaching a differential diagnosis. Our findings confirmed that PITX2 variants are strongly associated with dental and umbilical anomalies, whereas the majority (70%) of FOXC1 carriers lack systemic features; however, our cohort is biased toward participants with ocular features.

In ARS, glaucoma is often challenging to treat and the intraocular pressure difficult to control, often requiring incisional surgery (trabeculectomy or glaucoma drainage implant) and in some cases repeated surgical procedures.5, 18 Standard medications and surgical procedures often have a lower success rate than in non-ARS glaucoma patients.29 In our study, 48% of individuals with glaucoma had advanced visual field loss and all had incisional surgery. This highlights the importance of early molecular diagnosis for effective monitoring and treatment options.

Although the exact mechanism by which ARS causes glaucoma is not fully understood, it is hypothesised that an arrested development of the anterior chamber angle structures during gestation (characterised by an incomplete maturation of the trabecular meshwork, an absent or poorly developed Schlemm’s canal and/or a high insertion of the iris) alters the aqueous humour flow, thereby increasing intraocular pressure and resulting in glaucoma.5 Broad phenotypic variability associated with FOXC1 and PITX2 variants has been reported before,11, 14, 17, 18 as it has in this study, although Shields5 previously reported that the severity of ocular defects did not correlate with the development of glaucoma. FOXC1 and PITX2 both encode developmental transcription factors expressed in a tightly regulated temporal and spatial manner during development. Therefore, it is likely that disruption to the protein expression or activity level might not be well tolerated. However, inter- and intra-familial variability is often reported,16, 17, 30 and is reflected by the variability in glaucoma phenotype within the families described here. Clinical heterogeneity of FOXC1 and PITX2 variants is likely to be explained by genetic modifiers, as suggested by the differing ocular phenotypes of Foxc1-deficient mice on different genetic backgrounds.31 However, these modifiers remain to be identified.

A limitation of the study is that not every family member was tested, although all first-degree relatives of mutation carriers were invited to participate. Therefore, it is possible that individuals with milder phenotypes exist in the population but were not included. In addition, recruitment was somewhat biased towards glaucoma since participants were part of an advanced glaucoma registry, although the registry includes participants with ARM irrespective of their glaucoma status. Finally, diagnoses were made by different treating specialists, which may have introduced some variation in the phenotypic descriptions.

In conclusion, 59% of FOXC1 and PITX2 carriers in our cohort had glaucoma. Variants in both genes were associated with a similar risk of glaucoma, with FOXC1 carriers displaying an earlier age of onset than PITX2 carriers. These findings have implications when counselling individuals and their family members about their risk of developing glaucoma following genetic testing results. Furthermore, one family member was diagnosed with PCG and five with POAG, suggesting that variants in FOXC1 and PITX2 may also contribute to the genetic architecture of POAG and PCG. Further sequencing of large patient cohorts will be needed to determine the contribution of these genes to other glaucoma subtypes.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by The RANZCO Eye Foundation (www.eyefoundation.org.au, Sydney, Australia), the Ophthalmic Research Institute of Australia, Glaucoma Australia (www.glaucoma.org.au, Sydney, Australia) and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centres of Research Excellence Grant 1023911 (2012-2016). JEC is an NHMRC Practitioner Fellow. KPB and AWH are supported by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship. The Centre for Eye Research Australia (CERA) received Operational Infrastructure Support from the Victorian Government. We thank Angela Chappell and Carly Emerson for the ophthalmic photographs and Bastien Llamas for Figures 3 and 4.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Idrees F, Vaideanu D, Fraser SG, Sowden JC, Khaw PT: A review of anterior segment dysgeneses. Surv Ophthalmol 2006; 51: 213–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields MB, Buckley E, Klintworth GK, Thresher R: Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome. A spectrum of developmental disorders. Surv Ophthalmol 1985; 29: 387–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alward WL: Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome in the age of molecular genetics. Am J Ophthalmol 2000; 130: 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch N, Kaback M: The Axenfeld syndrome and the Rieger syndrome. J Med Genet 1978; 15: 30–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields MB: Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome: a theory of mechanism and distinctions from the iridocorneal endothelial syndrome. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1983; 81: 736–784. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura DY, Swiderski RE, Alward WL et al: The forkhead transcription factor gene FKHL7 is responsible for glaucoma phenotypes which map to 6p25. Nat Genet 1998; 19: 140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mears AJ, Jordan T, Mirzayans F et al: Mutations of the forkhead/winged-helix gene, FKHL7, in patients with Axenfeld-Rieger anomaly. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 63: 1316–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semina EV, Reiter R, Leysens NJ et al: Cloning and characterization of a novel bicoid-related homeobox transcription factor gene, RIEG, involved in Rieger syndrome. Nat Genet 1996; 14: 392–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JC, del Bono EA, Haines JL et al: A second locus for Rieger syndrome maps to chromosome 13q14. Am J Hum Genet 1996; 59: 613–619. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson JG Jr, Hicks EL: Rieger's anomaly and glaucoma associated with partial trisomy 16q. Case report. Arch Ophthalmol 1987; 105: 323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Haene B, Meire F, Claerhout I et al: Expanding the spectrum of FOXC1 and PITX2 mutations and copy number changes in patients with anterior segment malformations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011; 52: 324–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann OJ, Ebenezer ND, Ekong R et al: Ocular developmental abnormalities and glaucoma associated with interstitial 6p25 duplications and deletions. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2002; 43: 1843–1849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delahaye A, Bitoun P, Drunat S et al: Genomic imbalances detected by array-CGH in patients with syndromal ocular developmental anomalies. Eur J Hum Genet 2012; 20: 527–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lines MA, Kozlowski K, Kulak SC et al: Characterization and prevalence of PITX2 microdeletions and mutations in Axenfeld-Rieger malformations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004; 45: 828–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis LM, Tyler RC, Volkmann Kloss BA et al: PITX2 and FOXC1 spectrum of mutations in ocular syndromes. Eur J Hum Genet 2012; 20: 1224–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honkanen RA, Nishimura DY, Swiderski RE et al: A family with Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome and Peters Anomaly caused by a point mutation (Phe112Ser) in the FOXC1 gene. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 135: 368–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perveen R, Lloyd IC, Clayton-Smith J et al: Phenotypic variability and asymmetry of Rieger syndrome associated with PITX2 mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2000; 41: 2456–2460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strungaru MH, Dinu I, Walter MA: Genotype-phenotype correlations in Axenfeld-Rieger malformation and glaucoma patients with FOXC1 and PITX2 mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007; 48: 228–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JN, Loomis SJ, Kang JH et al: Genome-wide association analysis identifies TXNRD2, ATXN2 and FOXC1 as susceptibility loci for primary open-angle glaucoma. Nat Genet 2016; 48: 189–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatima A, Wang Y, Uchida Y et al: Foxc1 and Foxc2 deletion causes abnormal lymphangiogenesis and correlates with ERK hyperactivation. J Clin Invest 2016; 126: 2437–2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry FB, Lines MA, Oas JM et al: Functional interactions between FOXC1 and PITX2 underlie the sensitivity to FOXC1 gene dose in Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome and anterior segment dysgenesis. Hum Mol Genet 2006; 15: 905–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souzeau E, Goldberg I, Healey PR et al: Australian and New Zealand Registry of Advanced Glaucoma: methodology and recruitment. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2012; 40: 569–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JC: Four novel mutations in the PITX2 gene in patients with Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome. Ophthalmic Res 2002; 34: 324–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisschuh N, Dressler P, Schuettauf F, Wolf C, Wissinger B, Gramer E: Novel mutations of FOXC1 and PITX2 in patients with Axenfeld-Rieger malformations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006; 47: 3846–3852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler S, Meyer-Marcotty P, Weisschuh N et al: Dental and craniofacial anomalies associated with Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome with PITX2 mutation. Case Rep Med 2010; 2010: 621984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Marcotty P, Weisschuh N, Dressler P, Hartmann J, Stellzig-Eisenhauer A: Morphology of the sella turcica in Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome with PITX2 mutation. J Oral Pathol Med 2008; 37: 504–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasutto F, Mauri L, Popp B et al: Whole exome sequencing reveals a novel de novo FOXC1 mutation in a patient with unrecognized Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome and glaucoma. Gene 2015; 568: 76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Trillo C, Sanchez-Sanchez F, Aroca-Aguilar JD et al: Hypo- and hypermorphic FOXC1 mutations in dominant glaucoma: transactivation and phenotypic variability. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0119272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal AK, Pehere N: Early-onset glaucoma in Axenfeld-Rieger anomaly: long-term surgical results and visual outcome. Eye (Lond) 2016; 30: 936–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatireddy S, Chakrabarti S, Mandal AK et al: Mutation spectrum of FOXC1 and clinical genetic heterogeneity of Axenfeld-Rieger anomaly in India. Mol Vis 2003; 9: 43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RS, Zabaleta A, Kume T et al: Haploinsufficiency of the transcription factors FOXC1 and FOXC2 results in aberrant ocular development. Hum Mol Genet 2000; 9: 1021–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.