Abstract

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is considered as one of the most important bacterial indicators of a healthy gut. We studied the effects of oral F. prausnitzii treatment on high-fat fed mice. Compared to the high-fat control mice, F. prausnitzii-treated mice had lower hepatic fat content, aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase, and increased fatty acid oxidation and adiponectin signaling in liver. Hepatic lipidomic analyses revealed decreases in several species of triacylglycerols, phospholipids and cholesteryl esters. Adiponectin expression was increased in the visceral adipose tissue, and the subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissues were more insulin sensitive and less inflamed in F. prausnitzii-treated mice. Further, F. prausnitzii treatment increased muscle mass that may be linked to enhanced mitochondrial respiration, modified gut microbiota composition and improved intestinal integrity. Our findings show that F. prausnitzii treatment improves hepatic health, and decreases adipose tissue inflammation in mice and warrant the need for further studies to discover its therapeutic potential.

Introduction

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is considered as one of the most important bacterial indicators of a healthy gut. It is the dominant member of Clostridium leptum subgroup accounting >5% of the total gut microbiota in healthy humans (Lay et al., 2005; Flint et al., 2012). The health-beneficial effects of F. prausnitzii stem from its ability to produce butyrate, which favorably modulates intestinal immune system, oxidative stress and colonocyte metabolism (Hamer et al., 2008; 2009). In addition, F. prausnitzii has been shown to secrete anti-inflammatory compounds, such as salicylic acid to its surrounding environment (Miquel et al., 2015; Quevrain et al., 2015). Besides, F. prausnitzii produces a microbial anti-inflammatory molecule, MAM protein with anti-inflammatory properties that is suggested to alleviate colitis in vivo and to decrease activation of nuclear factor-κB signaling (Quevrain et al., 2016). Recently, a number of studies have associated a decreased abundance of this bacterium in the gut with several human diseases. Among others, the low levels of F. prausnitzii have been detected in inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, obesity and diabetes (reviewed in Miquel et al., 2013), all of which are characterized either by food intolerance, inadequate calorie intake and/or abnormal energy metabolism.

As a proof of its anti-inflammatory properties, F. prausnitzii strain A2-165 has been shown to reduce colitis and inflammatory bowel disease in a mouse model (Sokol et al., 2008; Rossi et al., 2016). Similarly, F. prausnitzii A2-165 increased ovalbumin-specific T-cell proliferation and reduced the number of IFN-γ+ T cells in vitro (Rossi et al., 2016). In addition, we have found in humans that hepatic fat content >5% was associated with low F. prausnitzii abundance and increased adipose tissue inflammation independent of weight (Munukka et al., 2014). Hepatic fat accumulation may lead to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease that is the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic disorders and highly frequent in obese individuals (Pereira et al., 2015).

By far, most of the studies described above have evaluated the effects of F. prausnitzii A2-165 strain on the host, while the properties of ATCC 27766 strain have been scarcely studied. In one study, F. prausnitzii ATCC 27766 culture supernatant was found to exert protective effects on colitis in mice, probably via inhibition of Th17 differentiation, IL-17A secretion, by downregulating IL-6 and by upregulating IL-4 (Huang et al., 2016). Therefore, in this work, we were interested in determining more profoundly the effects of ATCC 27766 strain on mice physiology.

Materials and methods

In vitro cultures

F. prausnitzii ATCC 27766 pure cultures were maintained at +37 °C on yeast extract, casitone, fatty acid and glucose (YCFAG) agar plates (modified from Lopez-Siles et al., 2012), in Whitley A35 anaerobic workstation (Don Whitley Scientific, Shipley, UK). The cell solutions for the intragastric inoculation were prepared by suspending the cultured bacterial cells in PBS at an approximated cell density of 9 × 108 CFU per ml. The volume of a single inoculum, including ~2 × 108 bacterial cells, was 220 μl. The suspensions were prepared at the anaerobic atmosphere using anaerobic PBS, and the dosing syringes were sealed with parafilm to enable the viability of the bacteria prior to the inoculation.

Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the National Ethics Committee of animal experimentation in Finland (license: ESAVI/7258 /04.10.07/2014). Seven-week-old C57BL/6N female mice were purchased from Charles River laboratories (Lyon, France). At the age of 8 weeks, they were randomly divided into control high-fat diet (HFD), Control chow and F. prausnitzii-treatment groups (n=6 per group, three mice per cage), and were housed in individually ventilated cages under specific-pathogen-free conditions. During the treatment period, one mouse from HFD Control and one from F. prausnitzii-treatment group had to be excluded due to significant weight loss. The mice received food and water ad libitum, and were maintained on a 12/12 h light/dark cycle. The irradiated HFD (HFD, 58126 DIO Rodent Purified Diet w/60% energy) and the matching irradiated chow diet (58124 DIO Rodent Purified Diet w/10% energy) were purchased from Labdiet/Testdiet (Herfølge, Denmark). Approximately 2 × 108 F. prausnitzii (F. prausnitzii-treated group) cells in PBS or PBS (control groups) were inoculated intragastrically twice a week every 2 weeks. The body weight was measured in electronic scale (d=0.01 g) at the same time of day every week. Food intake was monitored at four different time points by weighing the consumed food in 24 h period.

Tissue collections, blood analyses, and liver AST and ALT analyses

After the 13-week treatment, the overnight fasted mice were anesthetized and blood was drawn by puncturing the heart. Serum glucose and glycerol were analyzed using the KONELAB 20XTi analyser (Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles, CA, USA). The subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue, liver and gastrocnemius muscle were harvested, weighed with electronic scale (d=0.01 g), immersed in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. For the subsequent analyses of protein and gene expression, as well as fat content measurements, the tissues were pulverized in liquid nitrogen to obtain a homogeneous mixture of whole tissues. To analyze aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), ~20 mg of pulverized livers were homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl2, 2 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol and 1 mm DTT), supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) using TissueLyzer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). After centrifugation at 12 000 g, AST and ALT were measured from soluble liver protein extracts with KONELAB 20XTi analyser.

Extraction and isolation of liver lipids

The lipids were isolated by a variation of the Folch method (Folch et al., 1957). Total lipids were extracted from ~30 mg pulverized liver by 2.5 ml chloroform:methanol (CHCl3:MeOH) (2:1, v/v), vortexed before and after addition of 0.8 ml water with 0.88% KCl. After centrifugation at 2000 g for 3 min, the lower CHCl3-rich phase was saved, and 2 ml CHCl3:MeOH (86:14, v/v) was added to the upper phase and the procedure repeated. Thereafter, the CHCl3-rich phased was pooled and evaporated to dryness under nitrogen. The triacylglycerol (TAG), phospholipid (PL) and cholesteryl ester fractions were isolated using a solid-phase extraction procedure with preconditioned Sep-Pak Vac 6cc Silica cartridges (Waters, Dublin, Ireland). After elution of cholesteryl esters with hexane:methyl tert-butyl ether (MtBE) (200:0.8, v/v), the TAG fraction was eluted with hexane:MtBE (96:4, v/v), the column was conditioned with hexane:acetic acid (100:0.2, v/v) and MtBE:acetic acid (100:0.2, v/v), and finally the PL fraction was eluted with MeOH:MtBE:H2O (32:5:2, v/v/v). The initial extraction solvent contained the internal standards triheptadecanoin (Larodan Fine Chemicals, Malmö, Sweden), dinonadecanoyl-phosphatidylcholine (Larodan Fine Chemicals, Malmö, Sweden) and cholesteryl pentadecanoate (Nu-Check-Prep, Elysian, MN, USA).

Preparation and gas chromatography analysis of fatty acid methyl esters

The fatty acids were analyzed as methyl esters, prepared by the sodium methoxide-catalyzed transesterification method (Christie, 1982), and analyzed with a Shimadzu (Duisburg, Germany) GC-2010 gas chromatograph (Duisburg, Germany) equipped with an AOC-20i auto injector and a flame ionization detector. A wall coated open tubular DB-23 column (60 m × 0.25 mm inner diameter, df 0.25 μm; Agilent Technologies, J.W. Scientific, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used. The program used to separate the fatty acid methyl esters had an initial oven temperature of 130 °C for 1 min, increased to 170 °C (6.5 °C per min), further increased to 220 °C (2.5 °C per min) held for 14.5 min, and finally increased to 230 °C (60 °C per min) and held for 3 min. The detector temperature was 280 °C and the injector temperature was 270 °C. The injection volume was 1 μl. Peak identification and fatty acid methyl ester response factors were based on the fatty acid methyl ester 37 reference mixture (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA) and quantification was carried out in relation to the internal standards.

Histological and immunohistochemical analyses

For immunohistochemical staining, 5 μm thick frozen liver sections were cut on a cryomicrotome (Leica CM 3000, Wetzlar, Germany) at −24 °C. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Oil Red O staining were performed as previously described (Weston et al., 2015). In addition, acetone-fixed liver tissues were stained with Cy3-conjugated anti-smooth muscle actin (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA; C6198, 1:200).

Adipose tissues were fixed in Tris-buffered zinc fixative (2.8 mm calcium acetate, 22.8 mm zinc acetate, 36.7 mm zinc chloride in 0.1 m Tris-buffer, pH 7.4). After paraffin and endogenous peroxidase removal, the sections were stained using Vectastain Elite ABC kit (PK-6104 Vector Laboratories, Cambridgeshire, UK) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The first-stage antibody was anti-mouse CD45 (clone 30F11, BD 553076) 1 μg per ml (overnight at +4 °C) or negative control antibody. Diaminobenzedine (Dako, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used as a chromogen and the sections were counterstained using Mayer’s hematoxylin.

Gene and protein expression analyses

Real-time quantitative PCR and western blot were performed as previously described by us (Pekkala et al., 2015). Real-time PCR analysis was carried out according to MIQE guidelines using in-house designed primers (from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), iQ SYBR Supermix and CFX96 Real-time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA, USA). The sequences of the primers used in quantitative PCR are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Western blots were carried out with primary antibodies from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA), and by scanning the blots using Odyssey CLX Infrared Imager of Li-COR and Odyssey anti-rabbit IRDye 800CW and anti-mouse IRDye 680RD (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) as secondary antibodies. The quantified bands were normalized to two Ponceau S-stained bands due to that there were differences in the levels of housekeeping proteins between the groups.

DNA extraction from stools and colon content

Stool samples were collected before the treatments and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Following the killing, the colon and cecum content was collected and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The samples were stored at −75 °C until further use. The microbial DNA was extracted from ~100 mg of the frozen samples with GXT Stool Extraction Kit VER 2.0 (Hain Lifescience GmbH, Nehren, Germany) combined with an additional homogenization by bead beating in 1.4 mm Ceramic Bead Tubes with MO BIO PowerLyzer 24 Bench Top Bead-Based Homogenizer (MO BIO Laboratories, Inc., CA, USA). The DNA concentrations of the extracts were measured with Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and the DNAs were stored at −75 °C.

Gut microbiota composition analysis

The microbiota composition of stool and gut content were analyzed with Illumina MiSeq (San Diego, CA, USA) next-generation sequencing approach. The 16S ribosomal RNA gene libraries were generated in a single PCR with the custom-designed dual-indexed primers containing the adapter and specific index sequences required for sequencing. The approach is described in Supplementary Methods.

Statistics

All data were checked for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk’s test in PASW 18.0 for Windows. Because of a small sample size and that most of the data were not normally distributed, the group differences in gene expression, protein phosphorylation levels, liver triglyceride content, and variables related to body composition and the number of leukocytes were analyzed by nonparametric tests using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (Armonk, NY, USA). First, differences between the groups were analyzed using Kruskal–Wallis test (for k samples), and second, the difference was identified and statistical significance determined using the Mann–Whitney U-test. The group differences in the gut microbiota composition were analyzed by the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test using JMP Pro 11 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA) and the statistical tools of QIIME pipeline. Taxonomic levels L2 (phyla) and L6 (genera) were studied.

Results

F. prausnitzii treatment improves hepatic AST and ALT, lipid profile, and enhances adiponectin signaling and lipid oxidation in mice liver

C57BL/6 mice on a HFD are widely used as a model for obesity and hepatic diseases (Takahashi et al., 2012). The HFD mice were treated with F. prausnitzii to study the effects of the bacterium on the host health and metabolism. The results were compared to those of mice on HFD (Control HFD) and chow diet (Control chow). The study outline and weight gain during the experiment are presented in Supplementary Figures S1A and B, respectively. In the F. prausnitzii-treated mice, weight gain was higher than in the Control chow group during weeks 1–4 and week 10 (P=0.017, 0.004, 0.004, 0.004 and 0.009, respectively).

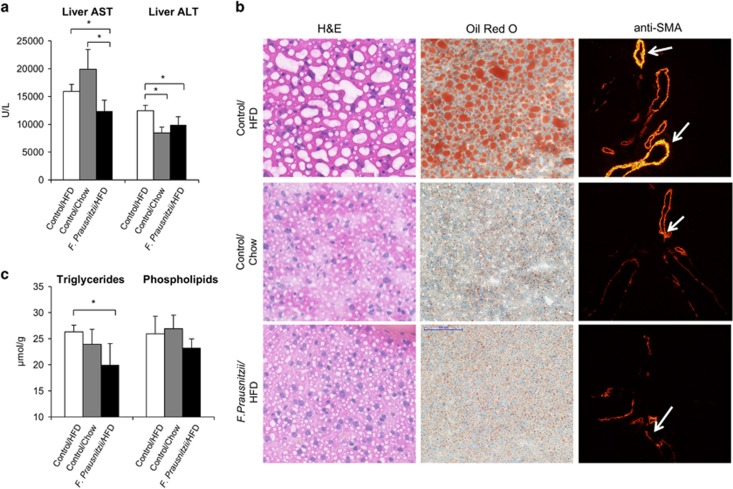

Compared to Control HFD, F. prausnitzii-treated mice had significantly lower hepatic AST (P=0.029) and ALT (P=0.029) values, and the Control chow lower ALT (Figure 1a). The Oil Red O staining of liver sections confirmed the consequences of HFD. Moreover, this was accompanied with ballooning and bright α-smooth muscle actin staining (Figure 1b). The mice treated with F. prausnitzii had significantly less triglycerides in liver (P=0.029) compared to the Control HFD mice (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii treatment decreases hepatic AST and ALT levels, fat content and improves histological changes caused by high-fat diet. The figure shows the effects of the treatments on (a) hepatic AST and ALT levels, (b) H&E, Oil Red O and α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) staining of the frozen liver sections. The SMA signal is high in vasculature of mice under high-fat diet. The arrows point to the highly positive vessels (looking overexposed and seen as bright yellow) in a high-fat diet mouse. The signal was weaker in other groups and the arrows point to those vessels as comparison (middle and bottom panels). Instead, the signal was weak outside the vasculature of the mice under high-fat diet and hardly visible in other groups. Note that the exposure time was exactly the same in all cases. Scale bar: 100 μm. (c) Total triglycerides and phospholipids contents. All data are presented as mean±s.d. n was 4–6 per group. The statistical significance was set to P<0.05, and the significant differences are presented with lines and * between the groups. The full colour version of this figure is available at ISME Journal online.

Gas chromatography analyses of hepatic lipid classes revealed a decrease in F. prausnitzii-treated mice in the molar percentages of 18:0 (stearate), 20:4n-6 (arachidonic acid), 20:5n-3 (eicosapentaenoic acid) and 22:6n-3 (docosahexanoic acid) in TAGs compared to the Control HFD mice (Table 1). Compared to the Control chow group, the Control HFD mice had higher proportions of most fatty acids in TAG except 18:1n-9 (oleic acid), 20:1n-9 (eicosenoic acid) and 20:2n-6 (eicosadienoic acid) that were lower in the Control HFD mice (P<0.05, Table 1). Compared to the Control HFD group, the molar percentages of several fatty acids in PLs were decreased in the Control chow group and the F. prausnitzii-treated group (Table 1). In contrast, 16:1 (palmitate), 18:1n-9, 20:2n-6 and 20:3n-6 (eicosatrienoic acid) increased in the PLs of the Control chow group (P<0.05 for all, Table 1), and 20:2n-6 and 20:4n-6 (arachidonic acid) in the F. prausnitzii-treated group (P<0.05 for both, Table 1). For cholesteryl esters, the F. prausnitzii-treated mice had higher proportions of 20:2n-6 and 20:3n-6, and lower levels of 16:0 and 20:1n-9 (P<0.05 for all, Table 1) compared to the Control HFD group. Compared to the Control HFD group, the Control chow group had higher levels of 16:1, 18:1n-9 and 20:3n-6, and lower proportions of 16:0, 18:0, 18:2n-6 (linoleic acid), 18:3n-3 (α-linoleic acid), 20:5n-3 and 22:6n-3 (P<0.05 for all, Table 1).

Table 1. Molar percentages of hepatic triacylglycerol (TAG), phospholipid (PL) and cholesteryl ester (CE) classes.

| Control/HFD, mol%, mean±s.d. | Control/chow, mol%, mean±s.d. | F. prausnitzii/HFD, mol%, mean±s.d. | P-value Control/HFD vs control/chow | P-value Control/HFD vs F. prausnitzii/HFD | P-value Control/chow vs F. prausnitzii/HFD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAG | ||||||

| 14:0 | 0.44±0.08 | 0.50±0.09 | 0.46±0.07 | 0.413 | 0.73 | 0.886 |

| 16:0 | 22.91±1.52 | 19.27±1.74 | 23.23±1.12 | 0.063 | 1.00 | 0.029 |

| 16:1 | 2.44±0.16 | 1.32±0.46 | 2.10±0.68 | 0.016 | 0.413 | 0.114 |

| 18:0 | 3.19±0.29 | 1.12±0.08 | 2.44±0.26 | 0.016 | 0.036 | 0.057 |

| 18:1n-9 | 39.41±0.72 | 60.86±1.43 | 41.52±2.46 | 0.029 | 0.686 | 0.029 |

| 18:2n-6 | 17.79±0.43 | 4.14±0.50 | 16.78±1.65 | 0.029 | 0.686 | 0.029 |

| 18:3n-3 | 0.83±0.12 | 0.18±0.09 | 0.73±0.07 | 0.016 | 0.393 | 0.057 |

| 18:3n-6 | 0.68±0.15 | 0.13±0.07 | 0.52±0.09 | 0.016 | 0.111 | 0.029 |

| 20:1n-9 | 0.33±0.03 | 0.64±0.10 | 0.40±0.07 | 0.029 | 0.200 | 0.029 |

| 20:2n-6 | 0.35±0.03 | 0.54±0.08 | 0.38±0.04 | 0.029 | 0.343 | 0.057 |

| 20:3n-6 | 0.42±0.16 | 0.22±0.12 | 0.40±0.06 | 0.111 | 0.571 | 0.229 |

| 20:4n-6 | 2.36±0.18 | 0.57±0.16 | 2.01±0.18 | 0.036 | 0.016 | 0.057 |

| 20:5n-3 | 0.51±0.01 | 0.12±0.04 | 0.35±0.01 | 0.029 | 0.036 | 0.057 |

| 22:6n-3 | 2.93±0.26 | 0.29±0.07 | 2.12±0.29 | 0.016 | 0.036 | 0.057 |

| PL | ||||||

| 14:0 | 0.08±0.01 | 0.08±0.01 | 0.06±0.01 | 0.556 | 0.063 | 0.016 |

| 16:0 | 21.71±0.45 | 20.25±0.73 | 20.30±1.31 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.841 |

| 16:1 | 0.57±0.06 | 2.03±0.23 | 0.48±0.09 | 0.008 | 0.190 | 0.016 |

| 18:0 | 17.04±0.87 | 12.29±0.72 | 17.97±0.81 | 0.008 | 0.095 | 0.008 |

| 18:1n-9 | 9.18±1.52 | 17.77±0.81 | 8.63±0.84 | 0.008 | 0.905 | 0.016 |

| 18:2n-6 | 11.34±0.50 | 6.56±0.43 | 10.87±1.13 | 0.008 | 0.690 | 0.008 |

| 18:3n-3 | 0.08±0.01 | 0.04±0.00 | 0.07±0.01 | 0.016 | 0.190 | 0.008 |

| 18:3n-6 | 0.18±0.01 | 0.16±0.03 | 0.14±0.02 | 0.286 | 0.032 | 0.222 |

| 20:1n-9 | 0.24±0.02 | 0.21±0.04 | 0.11±0.02 | 0.286 | 0.029 | 0.016 |

| 20:2n-6 | 0.07±0.01 | 1.74±0.60 | 0.28±0.03 | 0.286 | 0.029 | 0.016 |

| 20:3n-6 | 0.74±0.06 | 1.98±0.27 | 1.09±0.17 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.008 |

| 20:4n-6 | 20.04±0.58 | 19.85±1.19 | 21.18±1.38 | 1.000 | 0.150 | 0.008 |

| 20:5n-3 | 0.31±0.08 | 0.15±0.02 | 0.27±0.09 | 0.008 | 0.548 | 0.151 |

| 22:6n-3 | 14.01±1.75 | 9.72±0.49 | 13.88±1.60 | 0.008 | 0.841 | 0.008 |

| CE | ||||||

| 14:0 | 0.68±0.05 | 0.57±0.08 | 0.47±0.10 | 0.057 | 0.034 | 0.157 |

| 16:0 | 23.96±0.24 | 19.11±1.73 | 22.10±2.20 | 0.057 | 0.077 | 0.157 |

| 16:1 | 2.52±0.26 | 6.83±0.58 | 2.11±0.56 | 0.034 | 0.248 | 0.034 |

| 18:0 | 2.6±0.33 | 1.02±0.17 | 2.46±0.16 | 0.034 | 0.289 | 0.050 |

| 18:1n-9 | 37.60±0.75 | 57.44±0.88 | 43.20±6.89 | 0.050 | 0.289 | 0.034 |

| 18:2n-6 | 16.36±0.542 | 3.42±0.64 | 13.33±2.02 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.050 |

| 18:3n-3 | 0.79±0.02 | 0.07±0.01 | 0.45±0.17 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.050 |

| 18:3n-6 | 0.60±0.03 | 0.15±0.04 | 0.42±0.10 | 0.034 | 0.100 | 0.050 |

| 20:1n-9 | 0.48±0.33 | 0.68±0.11 | 0.62±0.48 | 0.400 | 0.289 | 0.050 |

| 20:2n-6 | 0.043±0.20 | 0.47±0.08 | 0.34±0.03 | 0.289 | 0.773 | 0.034 |

| 20:3n-6 | 0.42±0.019 | 0.12±0.03 | 0.46±0.15 | 0.034 | 0.724 | 0.050 |

| 20:4n-6 | 2.15±0.11 | 0.42±0.17 | 1.67±0.30 | 0.057 | 0.021 | 0.057 |

| 20:5n-3 | 0.42±0.02 | 0.01±0.00 | 0.22±0.11 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.050 |

| 22:6n-3 | 2.51±10.20 | 0.16±0.05 | 1.73±0.83 | 0.034 | 0.480 | 0.100 |

Abbreviation: HFD, high-fat diet.

All data are presented as mean±s.d. n was 4–6 per group. The statistical significance was set to P<0.05. The statistically significant values are indicated in bold.

The reduced hepatic fat content was not due to changes in serum glycerol and glucose that are substrates of lipid synthesis (Supplementary Figure S2A). In addition, no significant differences in food intake were found between the groups in long term (Supplementary Figure S2B). However, at one measurement point at the beginning of the treatments, compared to the HFD Control group, the other groups consumed less food (Supplementary Figure S2B).

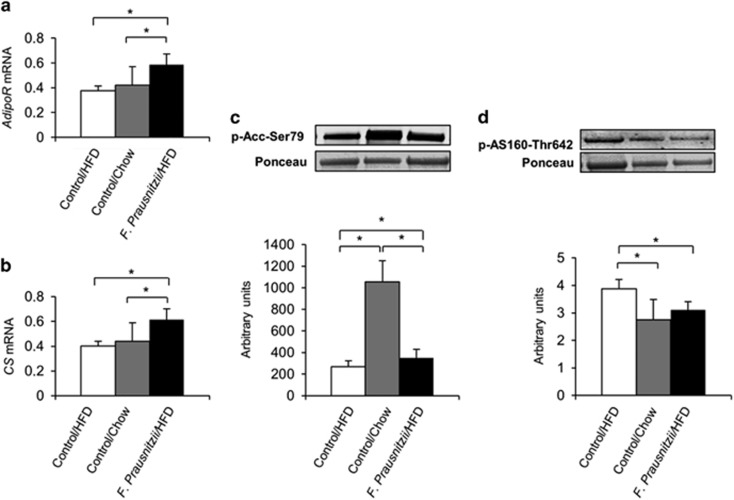

Despite the lower triglyceride levels and fat content in the liver, the F. prausnitzii-treated mice and the Control chow mice expressed more triglyceride-synthesizing diacylglycerol-acyltransferase, DGAT2 (P=0.008 and P=0.009, respectively, Supplementary Figure S3A) and fatty acid-synthesizing acetyl coenzyme carboxylase, Acc2 (P=0.029 and P=0.016, respectively, Supplementary Figure S3A) than the HFD control group. The lipid clearance in the F. prausnitzii-treated mice was likely increased, as these mice expressed more lipid metabolism-regulating adiponectin receptor, AdipoR (P=0.008, Figure 2a) and lipid-oxidizing citrate synthase, CS (P=0.008, Figure 2b). In addition, the F. prausnitzii-treated mice had more Ser79-phosphorylated Acc2 that turns the fatty acid metabolism onto oxidation instead of synthesis (P=0.048, Figure 2c) (Ha et al., 1994). In turn, less phosphorylated AS160 in the F. prausnitzii-treated mice compared to the HFD control group (P=0.043, Figure 2d) may indicate decreased glucose uptake for fat synthesis, as AS160 promotes the translocation of GLUT4 glucose transporters to the cell membrane (Lansey et al., 2012). The expression of CDKN1A and DDIT4, whose reduced expression has been associated with fibrosis and overactive mTOR signaling, respectively (Aravinthan et al., 2014; Williamson et al., 2014) was highest in the F. prausnitzii-treated mice (P<0.05 for both, Supplementary Figure S3B).

Figure 2.

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii treatment enhances adiponectin signaling and lipid oxidation in liver. The figure shows the effects of the treatments on (a) the expression of adiponectin receptor (AdipoR) mRNA, (b) the expression of citrate synthase (CS) mRNA, as well as (c) the phosphorylation levels of acetyl coenzyme carboxylase (Acc) and (d) the phosphorylation levels of AS160. mRNA, messenger RNA.

When compared to the HFD Control group, the direction of the effects of the F. prausnitzii treatment was almost exclusively the same as in the chow diet except that the chow diet did not increase CS and AdipoR (Figures 2a and b), but increased insulin receptor IRβ (P=0.008, Supplementary Figure S3C), while the F. prausnitzii-treated mice had a nonsignificant trend toward increased IRβ expression (P=0.09, Supplementary Figure S3C).

The participation of other peripheral tissues in hepatic fat accumulation has been recognized (Deivanayagam et al., 2008; Lomonaco et al., 2012), and therefore we further studied the molecular changes in the visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue as well as gastrocnemius muscles.

F. prausnitzii treatment increased adiponectin expression and insulin sensitivity, and decreased inflammation in the visceral adipose tissue

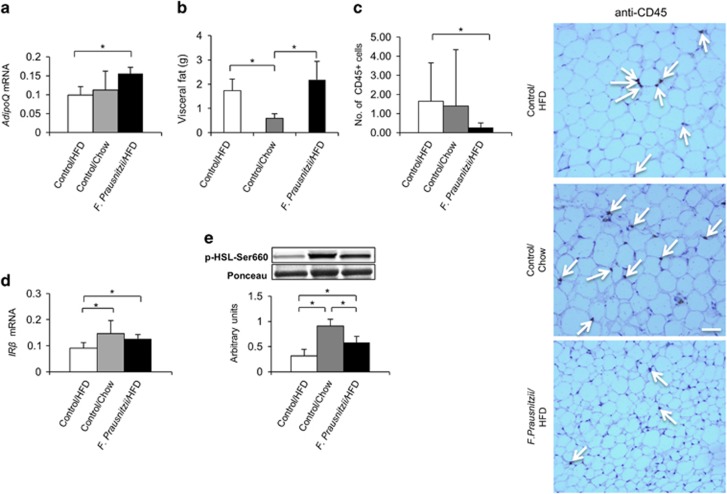

The visceral adipose tissue drains to the portal vein and therefore liver is directly exposed to, for example, adipokines secreted by this tissue (Rytka et al., 2011). Importantly, the expression of visceral fat-specific adipokine adiponectin that enhances fat oxidation in the liver was increased in the F. prausnitzii-treated mice compared to the HFD control group (AdipoQ, P=0.029, Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

F. prausnitzii treatment increases adiponectin expression and insulin sensitivity, and decreases inflammation in the visceral adipose tissue. The figure shows the effects of the treatments on (a) the expression of adiponectin (AdipoQ) mRNA, (b) the visceral fat mass indicated in grams (g), (c) the number of CD45-positive leukocytes in the histological samples/high power field and the histological stainings (the arrows point toward the CD45-positive brown cells), scale bar: 100 μm, (d) the expression of insulin receptor β (IRβ) mRNA, and (e) the phosphorylation levels of hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL). All data are presented as mean±s.d. n was 4–6 per group. The statistical significance was set to P<0.05, and the significant differences are presented with lines and * between the groups. mRNA, messenger RNA.

The increased fat mass in obesity-related metabolic disorders is associated with infiltrations of leukocytes to the adipose tissue, which subsequently exacerbates insulin resistance (Olefsky and Glass, 2010). Despite the higher visceral adipose tissue mass compared to the Control chow group (P=0.006, Figure 3b), compared to Control HFD group, the F. prausnitzii-treated mice had significantly reduced number of CD45-positive leukocytes (P=0.006, Figure 3c) that were determined from the histological samples. Consequently, the visceral adipose tissue of the F. prausnitzii-treated mice was more insulin sensitive in terms of increased IRβ expression (P=0.016, Figure 3d) and insulin-responsive hormone-sensitive lipase phosphorylation (P=0.021, Figure 3e).

Compared to the HFD, the chow diet again resulted in similar insulin signaling-related changes as the F. prausnitzii treatment (Figures 3d and e) suggesting that the treatment was able to protect from some deleterious effects of the HFD. The circumstance that F. prausnitzii-treated mice had higher visceral fat mass than the chow mice may be explained by the fact that the chow group likely oxidized more fat due to a higher expression of Acc2 (P=0.014, Supplementary Figure S4A), which also was more phosphorylated (P=0.014, Supplementary Figure S4B).

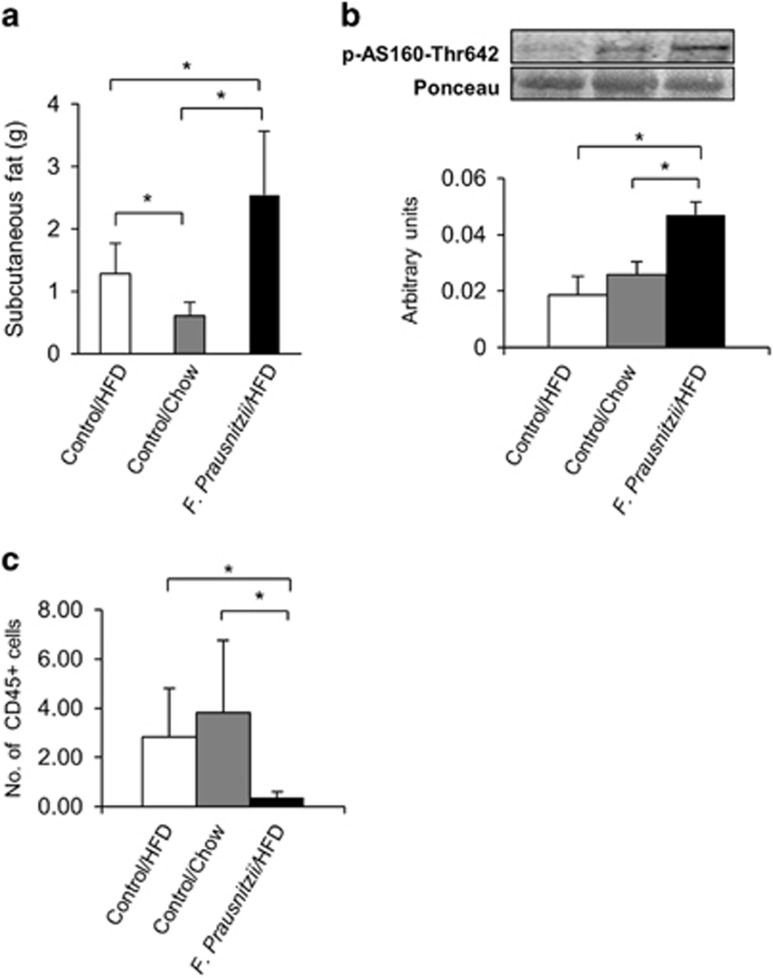

F. prausnitzii treatment reduced inflammation and affected the phosphorylation of glucose-uptake-related protein in the subcutaneous adipose tissue

It has been suggested that in obesity the glucose uptake by the adipose tissue is reduced (Virtanen et al., 2002). However, though the F. prausnitzii-treated mice had higher subcutaneous fat mass than the Control HFD group (P=0.047) and the Control chow group (P=0.006, Figure 4a), the treatment significantly increased AS160 phosphorylation compared to both control groups (P<0.05 for both, Figure 4b). Compared to the HFD control group, the F. prausnitzii-treated mice had less CD45-positive cells (P<0.05, Figure 4c), which is an indication of reduced inflammation. No other major changes in response to the F. prausnitzii treatment were detected in the subcutaneous adipose tissue.

Figure 4.

F. prausnitzii treatment decreases inflammation and affects the phosphorylation of the glucose-uptake-related protein in the subcutaneous adipose tissue. The figure shows the effects of the treatments on (a) the subcutaneous fat mass, (b) the phosphorylation levels of glucose-uptake-related AS160 and (c) the number of CD45-positive leukocytes in the histological samples divided by the counted fields. All data are presented as mean±s.d. n was 4–6 per group. The statistical significance was set to P<0.05, and the significant differences are presented with lines and * between the groups.

The Control chow group expressed more Acc2 (P=0.016, Supplementary Figure S5A) that was more phosphorylated (P=0.014, Supplementary Figure S5B) compared to the HFD group. In addition, compared to the HFD, the chow diet increased hormone-sensitive lipase phosphorylation (P=0.01).

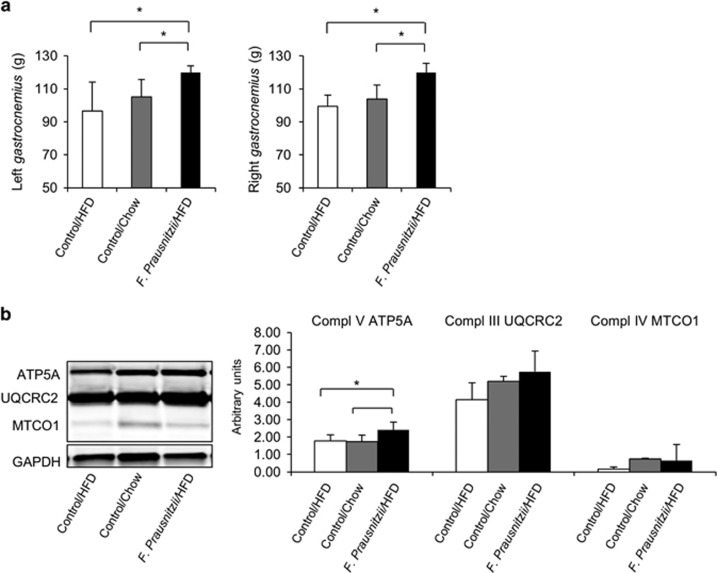

F. prausnitzii treatment increased gastrocnemius muscle size and the expression of mitochondrial respiratory chain protein ATP5A

Recently, it has been proposed that the gut microbiota may affect muscle growth and metabolism (Bindels and Delzenne, 2013). F. prausnitzii-treated mice had higher muscle mass than the HFD control group (for the left gastrocnemius, P=0.028, and for the right gastrocnemius, P=0.009, Figure 5a). However, the expression of muscle growth-related PGC1α protein was not increased (data not shown). Compared to the HFD control group, the F. prausnitzii-treated mice had higher expression levels of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex subunit ATP5A (P=0.047, Figure 5b), and a tendency for higher UQCRC2 and MTCO1 expression (P=0.05 for both, Figure 5b), while no differences were found in the expression of NDUFS88 and SDHB, or in the phosphorylation levels of Acc, AS160 and hormone-sensitive lipase (data not shown).

Figure 5.

F. prausnitzii treatment increases gastrocnemius muscle size and the expression of the mitochondrial respiratory chain protein ATP5A. The figure presents the effects of the treatments on (a) the gastrocnemius muscle mass in grams (g) and (b) the expression of the subunits of the mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes. All data are presented as mean±s.d. n was 4–6 per group. The statistical significance was set to P<0.05, and the significant differences are presented with lines and * between the groups.

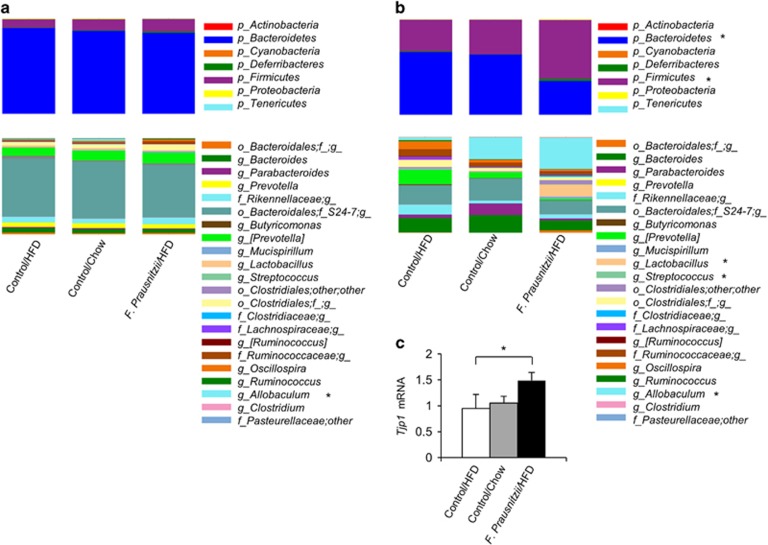

F. prausnitzii treatment changed the gut microbiota composition and increased the intestinal Tjp1 gene expression

In the stool samples collected before the treatment, no phylum level differences were seen between the treatment groups (Figure 6a), while in the samples collected after killing, the phylum level bacterial composition differed significantly between the groups (Figure 6b). Compared to the Control HFD group, the amount of phylum Bacteroidetes was significantly lower and the abundance of Firmicutes was significantly higher in the F. prausnitzii-treated mice (P<0.05 for both, Figure 6b). The same trend was noticed when F. prausnitzii-treated mice were compared to the Control chow group (P=0.07 for both, Figure 6b). In addition, phylum Cyanobacteria was more abundant in Control chow mice than in Control HFD and F. prausnitzii-treated mice (P<0.05 for both).

Figure 6.

F. prausnitzii treatment changes the gut microbiota composition. (a) Pretreatment stool samples. No phylum level differences were seen between the treatment groups. The genus Allobaculum being higher in chow control mice than in HFD control and F. prausnitzii-treated mice. (b) Post-treatment colon content samples. Compared to the HFD control group, the amount of phylum Bacteroidetes was significantly lower and the abundance of Firmicutes was significantly higher in the F. prausnitzii-treated mice. In addition, phylum Cyanobacteria was more abundant in chow control mice than in HFD control and F. prausnitzii-treated mice (P<0.05 for both). The abundances of genera Lactobacillus and Streptococcus increased in F. prausnitzii-treated mice compared to the HFD and normal chow controls. In addition, genus Allobaculum, which was not prevalent in the HFD controls, was highly abundant in the majority of the normal chow controls and in all F. prausnitzii-treated mice. (c) The expression of Tjp1 mRNA. Mean values ±s.d. are presented. n was 3–5 per group. The statistical significance was set to P<0.05 and the significant differences are presented with * next to the name of the bacteria. mRNA, messenger RNA.

In the bacterial genus level, the only pretreatment difference was the abundance of genus Allobaculum being higher in Control chow mice than in Control HFD and F. prausnitzii-treated mice (P<0.05 for both; Figure 6a). By contrast, several differences were seen in the post-treatment colon content samples between the groups, most prominent being the increased abundances of genera Lactobacillus and Streptococcus in F. prausnitzii-treated mice compared to the Control HFD and Control chow mice (P<0.05 for both; Figure 6b). In addition, genus Allobaculum, which was not prevalent in the Control HFD mice, was highly abundant in the majority of the Control chow mice and in all F. prausnitzii-treated mice (P=0.12 and P<0.05, respectively, Figure 6b).

The beneficial, anti-inflammatory bacteria have been shown to enhance intestinal barrier functions and integrity (Eun et al., 2011). Similarly, we found that compared to the HFD control group, F. prausnitzii treatment significantly increased the intestinal tight junction protein-encoding Tjp1 gene expression (P=0.043, Supplementary Figure S5A) that may indicate increased gut integrity.

Discussion

In this work, we found that the hepatic lipid content was lower in the F. prausnitzii-treated and Control chow mice than in the HFD Control mice. The findings of the lipid measurements, histological liver samples, as well as the AST and ALT of the F. prausnitzii-treated mice and the Control chow mice support each other, and suggest that these mice had healthier liver than the Control HFD mice.

Several molecular changes may explain the lower lipid content in either F. prausnitzii-treated mice or the Control chow group or in both. First, in addition to absorbing circulating fatty acids, hepatocytes synthesize fatty acids from dietary carbohydrates that reach the hepatocytes via the portal vein (Bechmann et al., 2012). We did not find any differences in food intake or blood glucose levels that would directly support a carbohydrate-dependent mechanism. However, compared to the HFD control group, the F. prausnitzii-treated mice had lower phosphorylation levels of AS160 that may lead to a decrease in glucose uptake and further reduced fat synthesis as the phosphorylated AS160 promotes translocation of GLUT4 glucose transporters to the cell membrane upon insulin stimulation (Wang et al., 2013; Brewer et al., 2014). Nevertheless, we did not measure glucose uptake in vivo. Second, an enhanced lipid clearance may have occurred due to higher expression levels of adiponectin receptor and higher phosphorylation levels of acetyl coenzyme carboxylase (Acc) in both F. prausnitzii-treated and chow mice. In liver, adiponectin signaling regulates both glucose and lipid metabolism (Liu et al., 2012). Adiponectin receptor activates AMPK that further acts a major regulator of lipid metabolism through direct phosphorylation of its substrates, such as Acc (Rogers et al., 2008). Acc in turn catalyzes the pivotal step of fatty acid synthesis pathway, and the phosphorylation of Acc at Ser79 inhibits the enzymatic activity of Acc turning the lipid metabolism on oxidation (Ha et al., 1994). In addition, increased expression of citrate synthase in the F. prausnitzii-treated mice may provide additional evidence of enhanced fatty acid β-oxidation and lipid clearance from liver as it shuttles the fatty acid-derived acetyl CoA-moieties to the tricarboxylic acid cycle (Turner et al., 2007). Similarly, an increased expression of DDIT4 may limit hyperactive mTORC1 signaling and further reduce lipogenesis (Williamson et al., 2014).

However, our findings about the molar percentages of some lipid classes are not completely in line with reports from humans and high-fat fed mice. Jordy et al. (2015) showed that 16:0 and 18:0 were increased in TAG of high-fat fed mice compared to normal chow, while we did not find an increase in 16:0. Depletion of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexanoic acid in TAG has been reported in steatosis and steatohepatosis (Videla et al., 2004; Puri et al., 2007), while our results show the depletion in F. prausnitzii-treated and chow mice that according to histology and ALT measurements have healthier liver. Nevertheless, several PLs were decreased compared to the Control HFD, which is in agreement with the higher amount of PLs detected in steatosis (Videla et al., 2004). In turn, eicosanoids are key mediators and regulators of inflammation and are generated from 20 carbon polyunsaturated fatty acids (Calder, 2011). Notably, 20:2n-6 (eicosadienoic acid) was increased in PLs of both chow and F. prausnitzii-treated mice and 20:4n-6 (arachidonic acid) of F. prausnitzii-treated mice compared to HFD Controls, and may be an indication of anti-inflammatory effects.

Recently, SNP rs762623 that reduces the expression of CDKN1A (Kong et al., 2007) has been shown to associate with fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients (Aravinthan et al., 2014). Therefore, an increased expression of CDKN1A in response to F. prausnitzii treatment may be an indication of reduced hepatic fibrosis. In agreement with decreased fibrosis, hepatic AST and ALT levels and α-smooth muscle actin, all markers of liver fibrosis (Naveau et al., 2009; Weston et al., 2015) were lower in F. prausnitzii-treated and Control chow mice.

The higher subcutaneous fat mass of the F. prausnitzii-treated mice may be explained by decreased β-oxidation and increased fat deposition due to lower Acc and citrate synthase levels. Generally, in obesity, adipocyte hypertrophy in the expanding adipose tissue leads to local hypoxia and subsequent cell death that drive leukocyte infiltration into the adipose tissue ensuing increased inflammation (Kanda et al., 2006). However, despite the higher fat mass, intensely decreased infiltration of CD45-positive leukocytes was observed in F. prausnitzii-treated group, which is in agreement with the known anti-inflammatory effects of this bacterium (Miquel et al., 2015; Quevrain et al., 2015).

In the visceral adipose tissue, F. prausnitzii treatment increased the expression of adiponectin, which, predominantly secreted by the visceral adipose tissue, has several insulin-sensitizing effects at the whole organism level (Caselli, 2014). In accordance, low concentrations of this adipokine have been associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease that are characterized by insulin resistance (Meier and Gressner, 2004). A recent study shed light to the possible mechanisms that connect the gut microbes to host’s adiponectin signaling by showing that the cell wall components of Gram-positive bacteria stimulated adiponectin secretion from mesenteric adipocytes, while lipolysaccharides from Gram-negative bacteria inhibited the secretion (Taira et al., 2015). In agreement with the findings of Taira et al. (2015), though initially F. prausnitzii was classified as Gram-negative, it resembles phylogenetically more Gram-positive than negative bacteria and therefore likely has similar cell wall properties to Gram-positive ones being able to stimulate adiponectin expression (Lopez-Siles et al., 2012).

It has been suggested that gut microbiota may also influence muscle size and metabolism (Bindels and Delzenne, 2013). Initially, it was proposed that intestine-derived Fiaf could increase muscular PGC1α expression, which is one of the master regulators of oxidative metabolism and prevents muscles from atrophy (Backhed et al., 2007). In this study, we did not find any differences between the groups in PGC1α expression. However, it should be noted that we only observed the end point situation of the treatments, and it may be that at some point during the muscle growth, the F. prausnitzii-treated mice may have displayed higher expression levels. Yet, at the time of killing, the oxidative metabolism may have been enhanced as these mice expressed higher levels of mitochondrial ATP5A that forms a part of the mitochondrial respiratory complex. Notwithstanding, the studies on the mechanistic effects of the so-called beneficial microbes on muscles are scarce (Bindels et al., 2012), and definitely are increasingly needed, as for instance, cancer-associated cachexia is an important health problem.

The F. prausnitzii treatment caused substantial changes in the gut microbiota, especially by promoting the growth of genera Lactobacillus and Streptococcus. In addition, the abundance of the genus Allobaculum was remarkably higher in both normal chow and F. prausnitzii-treated mice than in the HFD control group. Allobaculum genus consists of short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria and has been previously linked to weight reduction in mice (Ravussin et al., 2012). The changes in gut microbiota composition may be linked to the increased Tjp1 expression in the F. prausnitzii-treated mice. In agreement, health-beneficial probiotic bacteria have been shown to improve gut integrity through increased Tjp1 expression (Bomhof et al., 2014).

In conclusion, F. prausnitzii-treated mice had lower hepatic fat content, fibrosis, and AST and ALT than mice on HFD without treatment. The related molecular changes seem to involve increased fatty acid oxidation and adiponectin signaling in liver and increased adiponectin expression in visceral adipose tissue. In addition, the subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissues were less inflamed and more insulin sensitive in F. prausnitzii-treated mice.

Acknowledgments

We thank the laboratory technicians Mervi Matero, Kaisa-Leena Tulla, Risto Puurtinen, Heidi Isokääntä and Anna Aatisinki for the excellent technical assistance. This study has been financially supported by The Academy of Finland postdoctoral research fellow for SP (Grant ID 267719), by The Finnish Diabetes Research Foundation, Finnish Cultural foundation (Central and Southwest Finland funds for SP and EM, respectively), and by the Turku University foundation for MSc. AR, by Instrumentarium Research foundation and Diabetes Wellness foundation.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Aravinthan A, Mells G, Allison M, Leathart J, Kotronen A, Yki-Jarvinen H et al. (2014). Gene polymorphisms of cellular senescence marker p21 and disease progression in non-alcohol-related fatty liver disease. Cell Cycle 13: 1489–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhed F, Manchester JK, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. (2007). Mechanisms underlying the resistance to diet-induced obesity in germ-free mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 979–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechmann LP, Hannivoort RA, Gerken G, Hotamisligil GS, Trauner M, Canbay A. (2012). The interaction of hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism in liver diseases. J Hepatol 56: 952–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindels LB, Beck R, Schakman O, Martin JC, De Backer F, Sohet FM et al. (2012). Restoring specific lactobacilli levels decreases inflammation and muscle atrophy markers in an acute leukemia mouse model. PLoS One 7: e37971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindels LB, Delzenne NM. (2013). Muscle wasting: the gut microbiota as a new therapeutic target? Int J Biochem Cell Biol 45: 2186–2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomhof MR, Saha DC, Reid DT, Paul HA, Reimer RA. (2014). Combined effects of oligofructose and Bifidobacterium animalis on gut microbiota and glycemia in obese rats. Obesity 22: 763–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer PD, Habtemichael EN, Romenskaia I, Mastick CC, Coster AC. (2014). Insulin-regulated Glut4 translocation: membrane protein trafficking with six distinctive steps. J Biol Chem 289: 17280–17298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder PC. (2011). Fatty acids and inflammation: the cutting edge between food and pharma. Eur J Pharmacol 668: S50–S58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caselli C. (2014). Role of adiponectin system in insulin resistance. Mol Genet Metab 113: 155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie WW. (1982). A simple procedure for rapid transmethylation of glycerolipids and cholesteryl esters. J Lipid Res 23: 1072–1075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deivanayagam S, Mohammed BS, Vitola BE, Naguib GH, Keshen TH, Kirk EP et al. (2008). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with hepatic and skeletal muscle insulin resistance in overweight adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr 88: 257–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eun CS, Kim YS, Han DS, Choi JH, Lee AR, Park YK. (2011). Lactobacillus casei prevents impaired barrier function in intestinal epithelial cells. APMIS 119: 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint HJ, Scott KP, Louis P, Duncan SH. (2012). The role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 9: 577–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. (1957). A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 226: 497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha J, Daniel S, Broyles SS, Kim KH. (1994). Critical phosphorylation sites for acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity. J Biol Chem 269: 22162–22168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer HM, Jonkers D, Venema K, Vanhoutvin S, Troost FJ, Brummer RJ. (2008). Review article: the role of butyrate on colonic function. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 27: 104–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer HM, Jonkers DM, Bast A, Vanhoutvin SA, Fischer MA, Kodde A et al. (2009). Butyrate modulates oxidative stress in the colonic mucosa of healthy humans. Clin Nutr 28: 88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XL, Zhang X, Fei XY, Chen ZG, Hao YP, Zhang S et al. (2016). Faecalibacterium prausnitzii supernatant ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium induced colitis by regulating Th17 cell differentiation. World J Gastroenterol 22: 5201–5210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordy AB, Kraakman MJ, Gardner T, Estevez E, Kammoun HL, Weir JM et al. (2015). Analysis of the liver lipidome reveals insights into the protective effect of exercise on high-fat diet-induced hepatosteatosis in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 308: E778–E791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda H, Tateya S, Tamori Y, Kotani K, Hiasa K, Kitazawa R et al. (2006). MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J Clin Invest 116: 1494–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong EK, Chong WP, Wong WH, Lau CS, Chan TM, Ng PK et al. (2007). p21 gene polymorphisms in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 46: 220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansey MN, Walker NN, Hargett SR, Stevens JR, Keller SR. (2012). Deletion of Rab GAP AS160 modifies glucose uptake and GLUT4 translocation in primary skeletal muscles and adipocytes and impairs glucose homeostasis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 303: E1273–E1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lay C, Sutren M, Rochet V, Saunier K, Dore J, Rigottier-Gois L. (2005). Design and validation of 16 S rRNA probes to enumerate members of the Clostridium leptum subgroup in human faecal microbiota. Environ Microbiol 7: 933–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Yuan B, Lo KA, Patterson HC, Sun Y, Lodish HF. (2012). Adiponectin regulates expression of hepatic genes critical for glucose and lipid metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 14568–14573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomonaco R, Ortiz-Lopez C, Orsak B, Webb A, Hardies J, Darland C et al. (2012). Effect of adipose tissue insulin resistance on metabolic parameters and liver histology in obese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 55: 1389–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Siles M, Khan TM, Duncan SH, Harmsen HJ, Garcia-Gil LJ, Flint HJ. (2012). Cultured representatives of two major phylogroups of human colonic Faecalibacterium prausnitzii can utilize pectin, uronic acids, and host-derived substrates for growth. Appl Environ Microbiol 78: 420–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier U, Gressner AM. (2004). Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism: review of pathobiochemical and clinical chemical aspects of leptin, ghrelin, adiponectin, and resistin. Clin Chem 50: 1511–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquel S, Leclerc M, Martin R, Chain F, Lenoir M, Raguideau S et al. (2015). Identification of metabolic signatures linked to anti-inflammatory effects of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. MBio 6: e00300-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquel S, Martin R, Rossi O, Bermudez-Humaran LG, Chatel JM, Sokol H et al. (2013). Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and human intestinal health. Curr Opin Microbiol 16: 255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munukka E, Pekkala S, Wiklund P, Rasool O, Borra R, Kong L et al. (2014). Gut-adipose tissue axis in hepatic fat accumulation in humans. J Hepatol 61: 132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naveau S, Gaude G, Asnacios A, Agostini H, Abella A, Barri-Ova N et al. (2009). Diagnostic and prognostic values of noninvasive biomarkers of fibrosis in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 49: 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olefsky JM, Glass CK. (2010). Macrophages, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Annu Rev Physiol 72: 219–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekkala S, Munukka E, Kong L, Pollanen E, Autio R, Roos C et al. (2015). Toll-like receptor 5 in obesity: the role of gut microbiota and adipose tissue inflammation. Obesity 23: 581–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira K, Salsamendi J, Casillas J. (2015). The global nonalcoholic fatty liver disease epidemic: what a radiologist needs to know. J Clin Imaging Sci 5: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri P, Baillie RA, Wiest MM, Mirshahi F, Choudhury J, Cheung O et al. (2007). A lipidomic analysis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 46: 1081–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quevrain E, Maubert MA, Michon C, Chain F, Marquant R, Tailhades J et al. (2015). Identification of an anti-inflammatory protein from Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a commensal bacterium deficient in Crohn's disease. Gut 65: 415–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quevrain E, Maubert MA, Michon C, Chain F, Marquant R, Tailhades J et al. (2016). Identification of an anti-inflammatory protein from Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a commensal bacterium deficient in Crohn's disease. Gut 65: 415–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravussin Y, Koren O, Spor A, Leduc C, Gutman R, Stombaugh J et al. (2012). Responses of gut microbiota to diet composition and weight loss in lean and obese mice. Obesity 20: 738–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers CQ, Ajmo JM, You M. (2008). Adiponectin and alcoholic fatty liver disease. IUBMB Life 60: 790–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi O, van Berkel LA, Chain F, Tanweer Khan M, Taverne N, Sokol H et al. (2016). Faecalibacterium prausnitzii A2-165 has a high capacity to induce IL-10 in human and murine dendritic cells and modulates T cell responses. Sci Rep 6: 18507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytka JM, Wueest S, Schoenle EJ, Konrad D. (2011). The portal theory supported by venous drainage-selective fat transplantation. Diabetes 60: 56–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, Lakhdari O, Bermudez-Humaran LG, Gratadoux JJ et al. (2008). Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 16731–16736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taira R, Yamaguchi S, Shimizu K, Nakamura K, Ayabe T, Taira T. (2015). Bacterial cell wall components regulate adipokine secretion from visceral adipocytes. J Clin Biochem Nutr 56: 149–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Soejima Y, Fukusato T. (2012). Animal models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. World J Gastroenterol 18: 2300–2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner N, Bruce CR, Beale SM, Hoehn KL, So T, Rolph MS et al. (2007). Excess lipid availability increases mitochondrial fatty acid oxidative capacity in muscle: evidence against a role for reduced fatty acid oxidation in lipid-induced insulin resistance in rodents. Diabetes 56: 2085–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HY, Ducommun S, Quan C, Xie B, Li M, Wasserman DH et al. (2013). AS160 deficiency causes whole-body insulin resistance via composite effects in multiple tissues. Biochem J 449: 479–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston CJ, Shepherd EL, Claridge LC, Rantakari P, Curbishley SM, Tomlinson JW et al. (2015). Vascular adhesion protein-1 promotes liver inflammation and drives hepatic fibrosis. J Clin Invest 125: 501–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Videla LA, Rodrigo R, Araya J, Poniachik J. (2004). Oxidative stress and depletion of hepatic long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids may contribute to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Free Radic Biol Med 37: 1499–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DL, Li Z, Tuder RM, Feinstein E, Kimball SR, Dungan CM. (2014). Altered nutrient response of mTORC1 as a result of changes in REDD1 expression: effect of obesity vs. REDD1 deficiency. J Appl Physiol 117: 246–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen KA, Lonnroth P, Parkkola R, Peltoniemi P, Asola M, Viljanen T et al. (2002). Glucose uptake and perfusion in subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue during insulin stimulation in nonobese and obese humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87: 3902–3910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.