Abstract

Host-associated microbiomes are increasingly recognized to contribute to host disease resistance; the temporal dynamics of their community structure and function, however, are poorly understood. We investigated the cutaneous bacterial communities of three newt species, Ichthyosaura alpestris, Lissotriton vulgaris and Triturus cristatus, at approximately weekly intervals for 3 months using 16S ribosomal RNA amplicon sequencing. We hypothesized cutaneous microbiota would vary across time, and that such variation would be linked to changes in predicted fungal-inhibitory function. We observed significant temporal variation within the aquatic phase, and also between aquatic and terrestrial phase newts. By keeping T. cristatus in mesocosms, we demonstrated that structural changes occurred similarly across individuals, highlighting the non-stochastic nature of the bacterial community succession. Temporal changes were mainly associated with fluctuations in relative abundance rather than full turnover of bacterial operational taxonomic units (OTUs). Newt skin microbe fluctuations were not correlated with that of pond microbiota; however, a portion of community variation was explained by environmental temperature. Using a database of amphibian skin bacteria that inhibit the pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), we found that the proportion of reads associated with ‘potentially’ Bd-inhibitory OTUs did not vary temporally for two of three newt species, suggesting that protective function may be maintained despite temporal variation in community structure.

Introduction

Host-associated microbial communities have vital roles for the hosts on which they reside (for example, Stappenbeck et al., 2002; Rakoff-Nahoum et al., 2004; Dethlefsen et al., 2007; Engel and Moran, 2013). In particular, symbiotic bacterial communities are increasingly recognized in mediating protection against pathogens in multiple hosts (Rosenberg et al., 2007; Woodhams et al., 2007; Khosravi and Mazmanian, 2013; Fraune et al., 2014), by modulating and contributing to host immunity (Eberl, 2010; Chung et al., 2012; Gallo and Hooper, 2012; Krediet et al., 2013). Changes in microbiota have also been linked to disease (Stecher et al., 2007; Stecher and Hardt, 2008; Becker et al., 2015). Although in the framework of wildlife and human diseases, disease risk, infection prevalence and infection intensity are known to vary seasonally and across time (Altizer et al., 2006; Grassly and Fraser, 2006; Savage et al., 2011; Langwig et al., 2015), the impact of temporal fluctuations in host microbiota on disease risk has been studied in comparatively few systems.

In amphibians, cutaneous microbes are an important first line of defense against skin pathogens and can reduce disease susceptibility (for example, Becker and Harris, 2010; Bletz et al., 2013). Bacterial symbionts isolated from amphibian skin can inhibit growth of the fungus, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), in vitro (Harris et al., 2006; Flechas et al., 2012; Antwis et al., 2015; Woodhams et al., 2015), and can reduce detrimental effects associated with chytridiomycosis, the disease caused by Bd (Harris et al., 2009a, b; Vredenburg et al., 2011). Furthermore, such bacterial protection has been associated with production of particular bacterial metabolites, such as violacein (Becker et al., 2009). Chytridiomycosis has caused drastic declines of anuran populations in Central America and Australia (Berger et al., 1998; Lips et al., 2006). More recently, a new amphibian chytrid fungus, Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal) (Martel et al., 2013) has been found to pose a significant threat to salamander diversity in Europe and North America (Martel et al., 2014). With respect to Bd, infection prevalence and infection burden exhibits temporal variation (Kinney et al., 2011; Phillott et al., 2013; Longo et al., 2010, 2015), and such variation likely characterizes Bsal disease dynamics as well. One important factor driving this variation is temperature (Rohr et al., 2008; Bustamante et al., 2010), but overall the drivers of this variation are not well understood. Taking into consideration the defensive role of cutaneous microbiota, temporal variability of these communities may also be an important factor in such disease dynamics, especially considering population survival was linked to the proportion of amphibians with Bd-inhibitory bacteria in the western USA (Lam et al., 2010).

Similar to most other animal-associated microbiotas (Costello et al., 2009; Caporaso et al., 2011), limited data on temporal dynamics of amphibian skin communities exists (Longo et al., 2015), despite recent advances in our understanding of the ecology of these microbiomes. Amphibian microbial communities have been characterized for multiple species at single time-points, illustrating that they vary among species (McKenzie et al., 2012; Kueneman et al., 2014; Belden et al., 2015), across locations (Kueneman et al., 2014; Rebollar et al., 2016), among developmental stages (Kueneman et al., 2015; Sanchez et al., 2016) and depending on Bd presence and host susceptibility (Rebollar et al., 2016). Host properties of the mucosal environment in which bacteria reside, such as antimicrobial peptides, alkaloids, lysozymes, mucopolysaccharides and glycoproteins, (Rollins-Smith, 2009; Woodhams et al., 2014), and environmental microbiota of the surrounding habitat (Loudon et al., 2014; Walke et al., 2014; Fitzpatrick and Allison, 2014), influence host-associated microbial communities.

For amphibians, as well as for other hosts, if and to what extent symbiotic microbes change temporally is important given their defensive role against pathogens (Bletz et al., 2013), and for understanding the larger role they have in amphibian health. Their temporal dynamics is necessarily linked to the structure–function relationship. The prominent hypothesis in microbial community ecology is that community composition determines function (Robinson et al., 2010; Nemergut et al., 2013). Some studies support this hypothesis (Waldrop and Firestone, 2006; Kaiser et al., 2010; Fukami et al., 2010), whereas others support that structure and function are not inherently linked (Burke et al., 2011; Frossard et al., 2011; Belden et al., 2015; Louca et al., 2016). These alternative findings necessitate the following questions: if a bacterial community exhibits structural variation temporally, what are the functional implications? Does functional potential of the community parallel these structural changes or remain unchanged despite altered community structure? To determine whether temporal variation in amphibian skin microbiota influences protective function, we must study these communities across a time-series.

For amphibian microbiota, much of the available knowledge comes from isolated sampling events, providing snapshots of community structure and important insights into the factors structuring these communities. It remains unclear, however, how microbial communities on amphibian skin change through time, what factors drive this variation and how such variation may influence microbial function with respect to protection against pathogens. In this context, we test two main hypotheses: (1) amphibian cutaneous bacterial communities vary across time, and (2) changes in Bd-inhibitory predicted function are linked to temporal variation in the community structure, that is, functional changes will result from structural changes. Addressing these two hypotheses provides new insight into the structure–function relationship occurring in skin microbiomes.

To address our first hypothesis, we repeatedly sampled two biphasic newt species, Lissotriton vulgaris and Ichthyosaura alpestris, in a field survey, and also performed a semi-natural experiment, housing a third newt species, Triturus cristatus, in enclosures within field habitats. We characterize and compare newt cutaneous bacterial community diversity and structure through time within their aquatic phase. We test for associations of these communities with environmental temperature and environmental bacterial communities through time to determine the drivers of temporal variation. In addition, we characterize bacterial community structure across the aquatic-to-terrestrial transition. Newts develop as aquatic larvae, metamorphosing into adults which then maintain a biphasic life, spending part of each year within ponds (breeding season: March–May) and part within terrestrial habitats (June–February). This transition is particularly relevant as it applies a drastic restructuring of the skin in some species (Perrotta et al., 2012), including our focal species, the salamandrid newts. Such changes in skin morphology may result in temporal changes in cutaneous microbiota. To address the second hypothesis, we predict Bd-inhibitory function of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with a bioinformatic approach, using known functional information from a database of culture isolates tested in vitro for the ability to inhibit Bd growth (Woodhams et al., 2015). We subsequently determine whether this estimated function varies through time.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Sampling of three newt species was performed at semi-regular intervals (approximately once per week) between March and June 2015 at two locations, Kleiwiesen and Elm (Lower Saxony, Germany). L. vulgaris and T. cristatus, were sampled at Kleiwiesen, and I. alpestris, was sampled at Elm. These amphibian species were selected because of the likelihood of finding adequate sample sizes through time. To monitor temporal changes throughout their aquatic life phase we sampled (1) L. vulgaris free-swimming individuals on 17 March, 20 March, 24 March, 1 April, 14 April, 29 April and 29 May, (2) I. alpestris free-swimming individuals on 16 March, 18 March, 22 March, 28 March, 8 April and 22 April and (3) conducted a field mesocosm experiment with T. cristatus, allowing individuals to be tracked through time; sampling of mesocosm-housed newts occurred on 18/20 March, 25 March, 1 April, 8 April, 14 April, 22 April, 29 April and 6 May (see Mesocosm experiment section). To compare newt microbiota across the aquatic-to-terrestrial transition, we sampled terrestrial phase L. vulgaris and I. alpestris on 29 May at Kleiwiesen and 3 June at Elm. Table 1 provides sample sizes of each newt species on each sampling day.

Table 1. Sample sizes of amphibian cutaneous bacterial communities and pond water samples included in this study.

| Date |

Aquatic phase temporal sampling (16 March–29 May) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kleiwiesen |

Elm | |||

| L. vulgaris | T. cristatus | Environment | I. alpestris | |

| 16 March | 6 (8) | |||

| 17 March | 16 (20) | |||

| 18 March | 4 (6) | 10 (11) | ||

| 20 March | 11(19) | 6 (11) | 3 (3) | |

| 22 March | 10 (10) | |||

| 24 March | 18 (20) | 3 (3) | ||

| 25 March | 17 (17) | |||

| 28 March | 7 (7) | |||

| 1 April | 18 (19) | 15 (17) | 0 (1) | |

| 8 April | 16 (17) | 2 (2) | 15 (15) | |

| 14 April | 12 (12) | 16 (17) | 2 (2) | |

| 22 April | 16 (17) | 2 (2) | 16 (16) | |

| 29 April | 8 (8) | 13 (17) | 1 (2) | |

| 6 May | 10 (15) | 1 (2) | ||

| 29 May | 9 (10) | 3 (3) | ||

| Terrestrial–aquatic comparison | ||||

|

Kleiwiesen: 29 May; Elm: 22 April (Aq), 3 June (Ter) |

||||

| Kleiwiesen (L. vulgaris and I. alpestris) | Elm (I. alpestris) | |||

| Aquatic | 9 (9 Lv, 0 Ia) | 16 (16) | ||

| Terrestrial | 9 (3 Lv, 6 Ia) | 9 (12) | ||

Abbreviations: Aq, aquatic; Ia, Ichthyosaura alpestris; Lv, Lissotriton vulgaris; Ter, terrestrial.

These sample sizes represent post sequence filtering values. Numbers in parentheses indicate the respective number of individuals sampled in the field. The difference in these numbers is a result of the exclusion of samples because of low sequence coverage (<1000 reads).

Amphibians were captured in one of three ways: directly by gloved hands (clean nitrile gloves were used for each individual), dip nets or Ortmann’s funnel traps (Drechsler et al., 2010). Each captured individual was held with unique gloves, rinsed with 50 ml of filtered (0.22 μm) deionized water to remove debris and transient microbes, and swabbed on its ventral surface 10 times (1 time=an up and back stroke) using a sterile MW113 swab (Medical Wire and Equipment, Corsham, UK). Care was taken so the sampled surface did not contact the gloves after rinsing. Swabs were stored in unique sterile vials and transferred into a −20 °C freezer within 2 h after collection. Amphibians were returned to ponds immediately after sampling of all individuals was complete. Sampling resulted in 82 samples from I. alpestris, 111 samples from L. vulgaris and 134 samples from T. cristatus (see Table 1 for distribution of samples across dates).

iButton dataloggers (Thermochron, San Jose, CA, USA) were placed at both sampling locations to collect water temperature hourly. Loggers were placed at two locations within ponds where the water and base substrate meet and newts are commonly observed: (1) shallow water, approximately 20–30 cm and (2) deep water, approximately, 70–90 cm. At Kleiwiesen, pond water bacterial communities were sampled according to Walke et al. (2014) on each day in which newt sampling occurred. Twenty pond water samples were taken in total (see Table 1 for distribution of samples across dates).

Mesocosm experiment

For one newt species, T. cristatus, individuals were captured on 18 and 20 March 2015 and placed into wide polyester mesh mesocosms with zippered lids (mesh size: 0.5 cm diameter, height: 40 cm, diameter: 38 cm) to allow exact individuals to be tracked through time. This species was selected because of its large size and long uninterrupted aquatic phase making it less likely to escape and more suitable for long-term observation. The mesh size allowed entrance of prey; zippered lids prevented escape of newts or entry of other individuals. Mesocosms (n=9) were located at least 1 m apart within the ponds. Sediment and debris from the pond where newts were captured were placed in the base of all mesocosms, and a rock was used to submerge approximately 75% of each mesocosm within the pond, aiming to mimic natural conditions. Each mesocosm housed two individuals (a single individual in one case) (n=17) that were sampled weekly (total n=134, two individuals were released from their mesocosm before the final sampling date).

DNA extraction and sequencing

Whole-community DNA was extracted from swabs with the MoBio PowerSoil-htp 96-well DNA isolation kit (MoBio, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol with minor adjustments. A dual-index approach was used to PCR-amplify the V4 region of the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA gene with the 515F and 806R primers (Kozich et al., 2013). Pooled PCR amplicons of all samples were sequenced with paired-end 2 × 250 v2 chemistry on an Illumina MiSeq sequencer at the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research in Braunschweig, Germany (see Supplementary Methods). An aliquot of DNA extract from selected samples (Kleiwiesen: n=171, Elm: n=108) was used for real-time quantitative PCR to determine the occurrence of Bd and Bsal within the studied locations following Blooi et al. (2013).

Sequence processing

Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (MacQIIME v1.9.1) was used to process all sequence data unless otherwise stated (Caporaso et al., 2010). Briefly, forward and reverse reads were joined, quality-filtered and assigned to OTUs using an open reference strategy at 97% similarity with SILVA 119 (24 July 2014) as the reference database. OTUs making up <0.001% of the total reads were removed (Bokulich et al., 2013). All samples were rarefied at 1000 reads to allow inclusion of most samples and capture the majority of the diversity present within these bacterial communities. Samples with <1000 reads were therefore removed (see Supplementary Methods for details). After filtering, 287 newt samples remained for analyses along with 17 environmental samples (Table 1).

Sequence analysis

Temporal dynamics of skin-associated bacterial communities of three newt species in their aquatic phase was studied for a 3-month period between March and May 2015. Faith’s phylogenetic diversity was calculated as a measure of alpha diversity for all samples. Kruskal–Wallis tests were completed to compare diversity through time for L. vulgaris and I. alpestris in R (R Core Team, 2016). A mixed linear model was used for T. cristatus to account for repeated sampling and co-housing (lme4 package, Douglas et al., 2015). P-values were approximated with the KR method (afex package, Singmann et al., 2015). Beta diversity was calculated with the Bray–Curtis, weighted Unifrac and unweighted Unifrac metrics and temporal variation in community structure was assessed with permutational multivariate analyses of variance (PERMANOVA) with sampling date as the main fixed factor. For T. cristatus, mesocosm and individual (nested within mesocosm) were also included as factors.

Temporal changes in beta diversity for each species were calculated as the mean Bray–Curtis distance between the first sampling date and each subsequent date. To visualize temporal patterns in beta diversity among newt species, we completed a principal coordinate analysis on the Bray–Curtis distance matrix including all samples from all species and time-points. Axis values for PCo1 and PCo2 were extracted and plotted to visualize the time-series for each species.

To determine which OTUs were most responsible for the observed temporal variation across multiple time-points, a Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed for each newt species, with relative abundances of OTUs as the potential explanatory factors. This analysis was used to identify OTUs that were varying the most across multiple time-points. PCA analysis was completed with a modified OTU table containing only the Core-100 OTUs (see Supplementary Methods). From the PCA results, we identified the OTUs most responsible for the temporal variation as those yielding factor loading values of >0.1 on PC1 or PC2.

In addition, a hierarchical clustering method, unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean, along with Similarity Profile Analysis (SIMPROF), was used to evaluate similarity among individual newt communities and among the temporal pattern of PCA-identified OTUs. Bray–Curtis distances and Whittaker’s index of association were used for clustering of samples and PCA-identified OTUs, respectively. Unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean analysis and heat map visualization were completed in Primer 7 (Clarke and Gorley, 2015).

To explore drivers of the observed temporal variation in skin microbiota, we tested for associations between newt microbiota and environmental variables, including water temperature and aquatic bacterial community structure. Mantel tests were performed to test for associations between newt bacterial community structure and temperature, using average temperatures from 2 days before the sampling date to account for a likely lag effect of environmental temperature on host microbiota. Distance-based linear modeling was performed to determine the proportion of variation explained. To test for associations between the temporal patterns of newt and aquatic bacterial communities, Kendall’s tau rank correlations were performed for each of the PCA-identified OTUs; that is, for each of these OTUs, we tested for correlation between the temporal pattern in mean relative abundance on each newt species, and its relative abundance in pond water. Environmental microbiota correlations were only performed for newts sampled at Kleiwiesen where aquatic microbial community samples were available.

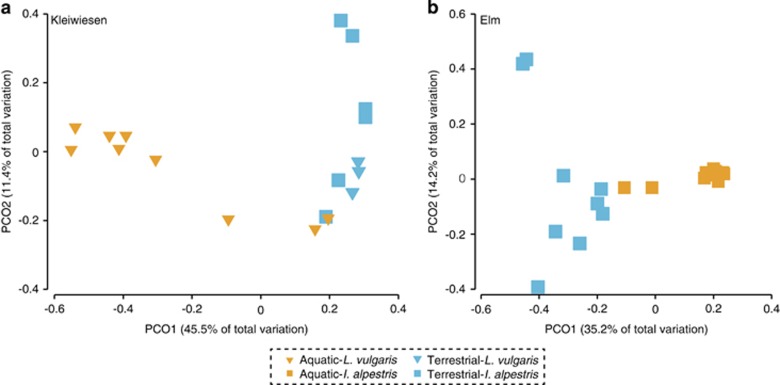

To investigate community changes across the aquatic-to-terrestrial transition, all terrestrially sampled individuals and aquatic individuals from the closest possible date from both Kleiwiesen (aquatic and terrestrial from the same day) and Elm (aquatic: 22 April; terrestrial: 3 June) were analyzed (Table 1). Terrestrial samples were only collected from L. vulgaris and I. alpestris. Beta diversity was calculated as described above, visualized with PCo Analysis and a PERMANOVA was completed to statistically test for differences between phases. OTUs that were differentially abundant between terrestrial and aquatic newts across both sampled locations were identified using the linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) method (Segata et al., 2011). LEfSe analysis was performed on a modified OTU table that contained only the Core-100 OTUs (see Supplementary Methods).

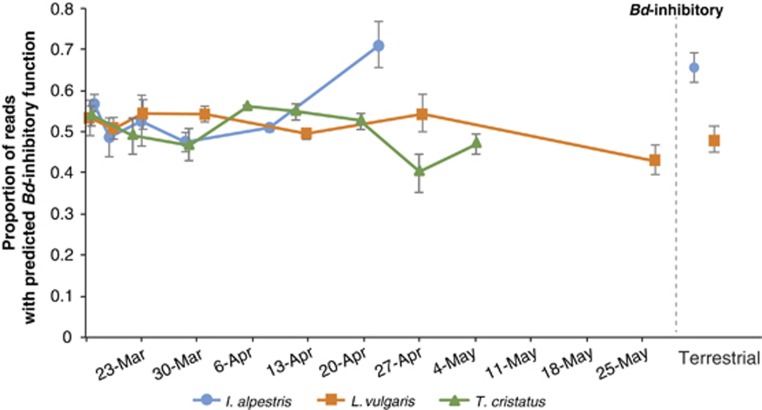

To assess our second hypothesis, looking at the structure–function relationship of cutaneous bacterial communities, we utilized a recently developed database containing over 1900 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequences from amphibian skin bacteria that have been tested for activity against the pathogen, Bd (Woodhams et al., 2015). Using this database, we determined which potentially Bd-inhibitory OTUs were present in our data set and calculated proportion of reads associated within these OTUs with respect to the full community (see Supplementary Methods). Kruskal–Wallis tests (L. vulgaris and I. alpestris) and mixed linear model (T. cristatus) were performed to test whether proportion of inhibitory reads varied through time. For the mixed linear model, significance was estimated using a likelihood ratio test. To compare terrestrial and aquatic individuals, we pooled data from both locations and used a linear mixed-effect model with life phase as a fixed effect and location (Kleiwiesen/Elm) as a random factor.

Results

Overall, 304 (287 newt and 17 environmental) samples were analyzed (Table 1). The rarified OTU table of skin microbiota samples contained 3503 unique bacterial OTUs, predominately from five main phyla: Proteobacteria, Bacteriodetes, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes and Verrucomicrobia.

Newt microbiota exhibits variation through time

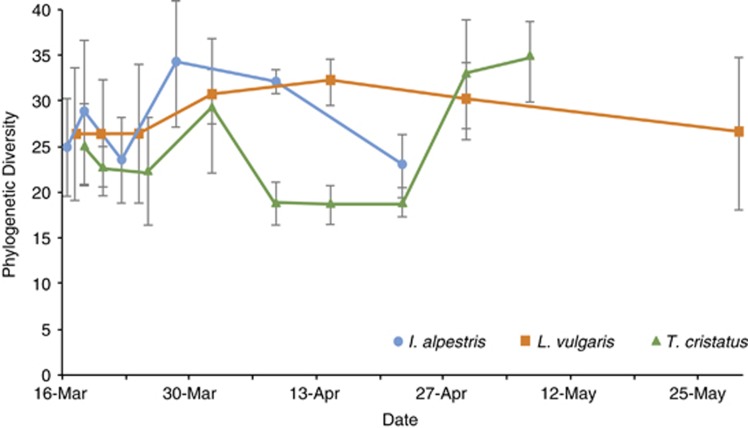

Phylogenetic diversity varied through time for all three newt species (analysis of variance : P<0.001, Figure 1). There was an increase in phylogenetic diversity in the second half of March in all species, followed by a decrease in April for I. alpestris and T. cristatus, and a subsequent increase in May for T. cristatus (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic diversity of cutaneous bacterial communities through time for the three European newt species studied. Points represent the mean diversity for all sampled newts on a given day for the respective newt species. Error bars represent s.e.m. See Supplementary Figure S1 for phylogenetic diversity (PD) of individuals of T. cristatus through time.

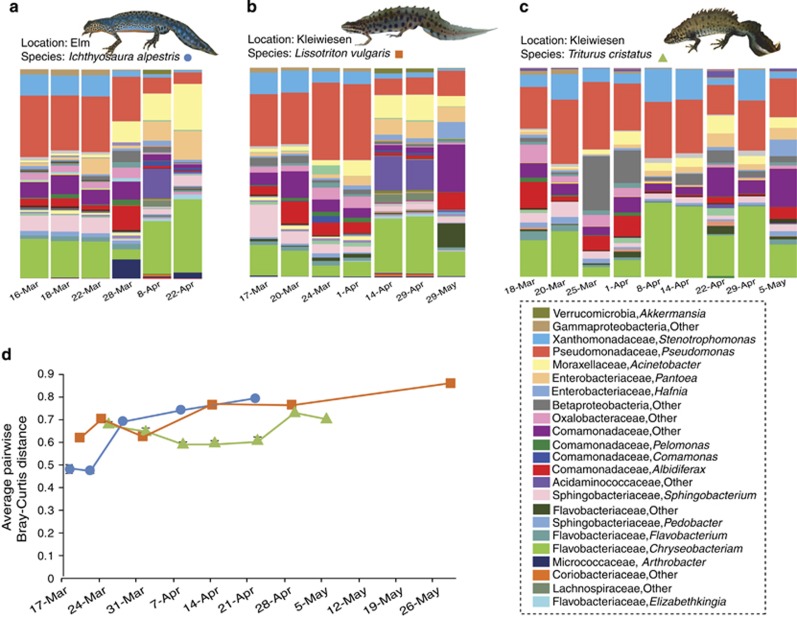

Cutaneous bacterial community structure on newts also significantly varied through time using Bray–Curtis (PERMANOVA: Pseudo-F=13.722 (I. alpestris), 8.3865 (L. vulgaris), 9.2361 (T. cristatus), P=0.001), weighted Unifrac (PERMANOVA: Pseudo-F=10.638 (I. alpestris), 8.747 (L. vulgaris), 13.469 (T. cristatus), P=0.001) and unweighted Unifrac (PERMANOVA: Pseudo-F=3.7736 (I. alpestris), 3.2635 (L. vulgaris), 3.5643 (T. cristatus), P=0.001). Mean relative abundance profiles of newt bacterial OTUs showed that community composition differed across time (Figure 2). For both I. alpestris and L. vulgaris, pairwise distances from the initial sampling point increased through time, but for T. cristatus distances were relatively constant (Figure 2). Unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean clustering showed that samples from the same or nearby dates had more similar community structures and samples typically clustered chronologically for each study species (Figure 3, Supplementary Figure S3). Similarity profile analysis (SIMPROF) revealed significant grouping among samples for each species (I. alpestris: Pi=12.864, P=0.001, L. vulgaris: Pi=8.86, P=0.001, T. cristatus: Pi=8.862, P=0.001).

Figure 2.

Temporal variation in host-associated skin bacterial communities of three European newt species. Genus-level relative abundance profiles of the Core-100 OTUs through time for (a) I. alpestris, (b) L. vulgaris, and (c) T. cristatus. (d) line graph of pairwise distance comparisons between each sampling date and the initial sampling date for each newt species, depicting the continued changes in community structure through time. Points represent the mean pairwise distances for all sampled newts on a given day for the respective newt species. Error bars represent s.e.m. See Supplementary Figure S2 for distance comparisons in individuals of T. cristatus through time.

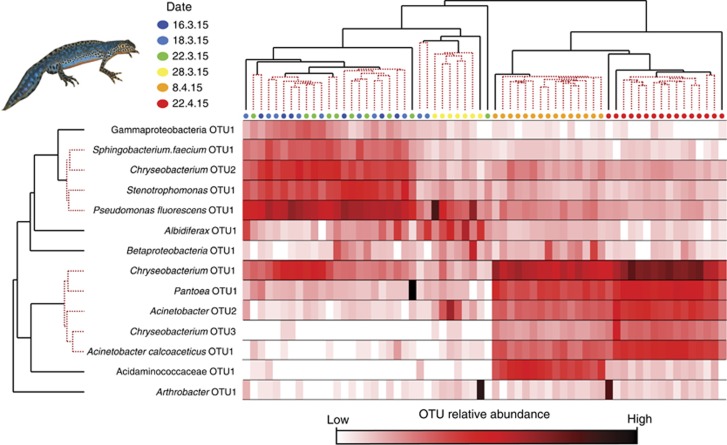

Figure 3.

Temporal patterns of bacterial OTUs found to be most responsible for the temporal variation of skin microbial communities on I. alpestris. Samples (columns) are clustered by unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) clustering of the Bray–Curtis distance matrix and OTUs (rows) are clustered using Whittaker’s index of association. UPGMA clustering of samples shows clustering by date and UPGMA clustering of bacterial OTUs showed that some OTUs followed similar temporal trajectories. SIMPROF results are indicated by the red-dotted lines of the UPGMA dendrograms; the transition of black to red-dotted lines indicates the point at which the null hypothesis is no longer rejected, that is, the branches no longer have internal structure and are homogeneous. Heat map displays the relative abundance of the OTUs within the community, with darker shades representing greater values. OTU names are given based on lowest taxonomic assignment with an OTU number specific to the SILVA or denovo cluster IDs. UPGMA and heatmaps for L. vulgaris and T. cristatus are presented in Supplementary Figure S3.

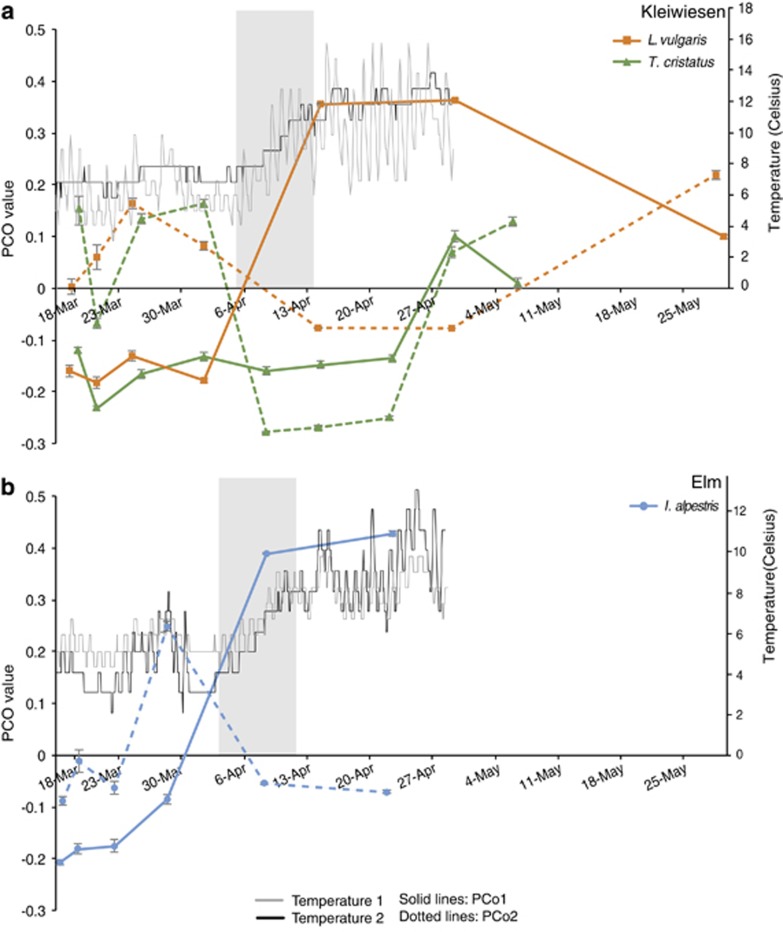

I. alpestris (Elm) and L. vulgaris (Kleiwiesen) exhibited similar transitions in bacterial community structure, whereas that of T. cristatus followed a different pattern (Figure 4). In late March–early April, there was a marked shift in PCo1 and PCo2 for L. vulgaris and I. alpestris and in PCo2 only for T. cristatus (Figure 4). For L. vulgaris and T. cristatus, there was also an observable shift in late April to May in both PCo axes (Figure 4). For T. cristatus, where exact individuals were tracked through time, we found that changes in community structure did not differ between mesocosms (date-by-mesocosm interaction Pseudo-F=1.0108, P=0.477), suggesting cutaneous bacterial communities were temporally changing in a similar manner across individuals, that is, they exhibited synchrony of community changes (Supplementary Figure S4).

Figure 4.

Temporal patterns in host-associated skin bacterial communities of three European newt species and water temperature patterns. (a) Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) axis 1 and 2 values through time for L. vulgaris and T. cristatus at Kleiwiesen. (b) PCoA axis 1 and 2 values through time for I. alpestris at Elm. Note the similar pattern in the PCO trends through time for L. vulgaris and I. alpestris. Water temperature data are only available until 29 April. Temperature 1 is from a logger placed in shallow water of the pond, and temperature 2 is from a logger placed in deep water. Gray boxes highlight the window in time where there was a steady increase in water temperature. Error bars represent s.e.m.

To identify OTUs most responsible for temporal variability of skin bacterial communities, we performed a PCA on the Core-100 OTU table for each species. The temporal Core-100 OTUs comprises 79, 68 and 46 OTUs for I. alpestris, L. vulgaris and T. cristatus, respectively. On average, these OTUs made up 69.6±15.1%, 59.7±6.1% and 70.8±12.5% of the community for the respective species. PC1 accounted for 75.4%, 70.2% and 70% of the variation, and PC2 accounted for 15.6% 15.7% and 19.3%, respectively, for I. alpestris, L. vulgaris and T. cristatus. Fourteen, eleven and nine OTUs were found to strongly influence the temporal variation in community structure for the three species, respectively (Supplementary Table S1). Four of these OTUs were found to strongly influence temporal variation for all three species: Chryseobacterium OTU1 (Flavobacteriaceae), Pantoea OTU1 (Enterobacteriaceae), Albidiferax OTU1 (Comamonadaceae) and Pseudomonas fluorescens OTU1 (Pseudomonadaceae) (Supplementary Table S1). Chryseobacterium OTU1 increased through time for all three newt species, while Pantoea OTU1 increase through time for I. alpestris and L. vulgaris, but remained more constant for T. cristatus (Figure 3). Pseudomonas fluorescens OTU1 decreased through time for I. alpestris and L. vulgaris, and remained more consistent for T. cristatus (Figure 3). Temporal patterns in relative abundance of the PCA-identified OTUs are shown in Figure 3 (I. alpestris) and Figure S3 (L. vulgaris and T. cristatus).

Multiple OTUs remained detectable through time. We observed seven, five and five OTUs, respectively, for I. alpestris, L. vulgaris and T. cristatus that were present on a minimum of 90% of individuals on all sampling days (Supplementary Table S2). Three of these OTUs were identified for all three newt species: Chryseobacterium OTU1 (Flavobacteriaceae), and two pseudomonad OTUs, Pseudomonas fluorescens OTU1 and Pseudomonas OTU2 (Pseudomonadaceae) (Supplementary Table S2).

Environmental drivers of community variation

Mantel tests showed a significant correlation between water temperature and newt bacterial community structure (P-values=0.001 for all species). Based on distance-based linear modeling, water temperature explained 24% of the variation for I. alpestris, 23% for L. vulgaris and 9% for T. cristatus (Supplementary Table S3). Pond bacterial community composition also varied through time (Supplementary Figure S5). We tested for correlations between average relative abundances of selected OTUs on newts and in the pond water. For L. vulgaris, no OTUs exhibited significant positive correlations, and there was one OTU (Flavobacteriaceae OTU1) that had a significant negative correlation (Kendall’s tau: z=−2.2738, P=0.023, τ=-0.949). For T. cristatus, only one OTU (Chryseobacterium OTU4) showed a significant positive correlation (Kendall’s tau: z=2.1954, P=0.028, τ=0.72). All correlation results are provided in Supplementary Table S4.

Cutaneous microbiota differs between life phases

Bacterial community structure differed between terrestrial and aquatic individuals at both locations (Figure 5, PERMANOVA: Pseudo-F=7.5428 (Kleiwiesen), 10.447 (Elm), P=0.001). Terrestrial individuals exhibited greater relative abundances of Pseudomonadaceae (terrestrial: 12.5/aquatic: 4.3%), Enterobacteriaceae (20.3/8.8%) and Rhodobacteriaceae (2.2/0.4%), whereas aquatic individuals showed greater relative abundances of Moraxellaceae (5.3/10.6%), Comamonadaceae (4.7/13.2%), Rhizobaceae (0.7/2.5%) and Flavobacteriaceae (13.8/23.8%) (Supplementary Figure S6). LEfSe analysis at the OTU-level revealed two OTUs from the 43 Core-100 OTUs that were significantly more abundant on aquatic newts and 12 OTUs that were more abundant on terrestrial newts across both locations (Supplementary Figure S6).

Figure 5.

Community structure of terrestrial and aquatic phase newts. PCO analysis of Bray–Curtis distance matrix of terrestrial and aquatic newt skin bacterial communities at Kleiwiesen (a) and Elm (b). Mean relative abundance profiles of terrestrial and aquatic individuals and LEfSe-identified differentially abundant OTUs are presented in Supplementary Figure S5.

Pathogen presence and stability of Bd-inhibitory function through time

Bd was present at both Kleiwiesen and Elm, however, Bsal was not detected. Of the 273 samples tested, 15 were positive for Bd (2 I. alpestris, 10 L. vulgaris and 3 T. cristatus) (Supplementary Table S5).

One hundred thirty-four OTUs from the newt temporal data set matched inhibitory OTUs from the amphibian bacteria database (Woodhams et al., 2015). Relative abundance of Bd-inhibitory reads (derived from the summation of rarified reads associated with all ‘potentially inhibitory’ OTUs, n=134) did not differ across time for L. vulgaris (Kruskal–Wallis chi-squared=6.6038, P=0.359) and T. cristatus (mixed linear model comparison: L. ratio=1.8709, P=0.1707) (Figure 6). I. alpestris did show significant differences among dates (Kruskal–Wallis chi-squared=29.599, P<0.001), and this was due to the proportion of inhibitory reads being greater on 22 April in comparison with all other dates (Wilcoxon post-hoc: P(fdr)<0.01). Proportion of Bd-inhibitory reads also did not differ between terrestrial and aquatic individuals (GLM: t=−1.1533, P=0.2529).

Figure 6.

Predicted Bd-inhibitory function is maintained through time for two of the three sampled newt species. Proportion of reads assigned to OTUs with known ‘Bd-inhibitory’ function for each sampled newt species. For the terrestrial data, Elm and Kleiwiesen are pooled together. Error bars represent s.e.m.

The observed functional stability resulted both from constancy of particular OTUs early in the season, and replacement by different OTUs later in the season (Supplementary Figure S5). For example, a Bd-inhibitory Pseudomonas fluorescens OTU (JQ691706.1.1490) is consistently present during the early time-points, whereas a Bd-inhibitory Chyrseobacterium OTU (KC734243.1.1310) increases in relative abundance at the later time-points for all three newt species. The top four OTUs, which constitute a large portion of the Bd-inhibitory reads, match with database OTUs with strong Bd-inhibitory signals (see Supplementary Methods): a Pseudomonas fluorescens OTU-JQ691706.1.1490 (80% 28/35 isolates), a Chryseobacterium OTU-KC734243.1.1310 (90% 28/31 isolates), a Stenotrophomonas OTU-HQ224659.1.1422 (100% 2/2 isolates) and a Pantoea OTU-HQ728209.1.1508 (62% 55/89 isolates) (Supplementary Figure S7).

Discussion

Temporal dynamics of host-associated microbiota has been identified as a gap in our ecological understanding of these communities (Grice and Segre, 2011; Rosenthal et al., 2011; Walter and Ley, 2011), and for many organisms, including amphibians, such dynamics are a foundational piece of knowledge for developing a thorough understanding of the functional role these communities have in host health (Rosenberg et al., 2007; Robinson et al., 2010; Fierer et al., 2012).

We hypothesized that amphibian skin microbiota would vary temporally within the aquatic phase. Our results show that, for all species, date had a significant effect on cutaneous bacterial community structure. L. vulgaris and I. alpestris showed strikingly similar temporal patterns in community structure despite being from different locations. However, the patterns observed in T. cristatus were different. Whether this observation reflects a true biological difference or was at least partly caused by environmental conditions within mesocosms, or repeated sampling of individuals, requires further study. Despite this restriction, these data from T. cristatus conclusively demonstrate that temporal changes observed in cutaneous microbiota are not caused by different individuals captured at different time-points. The consistent temporal trajectory in bacterial community structure among T. cristatus individuals suggests that non-stochastic, selective processes of community assembly and succession are at play.

The observed community variation is likely associated with fluctuations in external environmental conditions, including abiotic factors and environmental microbiota, as well as changes in host skin morphology and mucosal characteristics. The marked shift in community structure seen in L. vulgaris and I. alpestris in early April coincides directly with a steady increase in water temperatures at both locations. Water temperature was found to explain up to 24% of observed microbial variation depending on the host species, suggesting that external environmental parameters are in part dictating the temporal trajectory of these skin microbiotas. As amphibians are ectothermic, their body temperature matches that of the surrounding habitat. Temperature can directly influence growth of host-associated bacterial taxa (Daskin et al., 2014) and also influence community member interactions and antifungal capacity (Woodhams et al., 2014). Environmental factors, such as temperature, have been found to influence amphibian gut microbiota (Kohl and Yahn, 2016), and also affect microbial communities in surrounding habitats. For aquatic amphibians, such as aquatic phase newts, bacterioplankton is likely an important reservoir from which the skin is colonized, and such freshwater bacterial communities are known to vary temporally (Crump and Hobbie, 2005; rivers—Kent et al., 2007; Portillo et al., 2012; lakes—Jones et al., 2012; Shade et al., 2013; temporary pools—Carrino-Kyker and Swanson, 2008). Therefore, seasonal shifts in environmental microbiota could dictate host-associated microbiota variations. For terrestrial salamanders, soil provides a rich bacterial reservoir competing with established cutaneous communities, and such competition may explain the diverse skin microbiota observed (Loudon et al., 2014) and possibly its variation over time. In this study, however, temporal patterns of bacterial taxa on newts were not correlated with dynamics of the respective OTUs within the environment. This finding makes sense in the context of other studies that have found amphibian microbial communities are dominated by bacterial taxa that are rare in the environment (Walke et al., 2014; Rebollar et al., 2016); thus, we can expect different dynamics between these two communities.

The lack of association between the temporal dynamics of environmental microbiota and that of newts, suggests a heightened role of host-associated factors, such as changes in skin morphology and mucosal characteristics, in driving temporal patterns of newt skin microbiota. At the start of sampling newts had just migrated into breeding ponds; the period from mid-March to early April likely coincided with changes in skin morphology from the terrestrial to aquatic phase (Perrotta et al., 2012). This transitional process also involves increased skin sloughing, which is known to affect skin microbiota (Meyer et al., 2012; Cramp et al., 2014). Microbial changes may also be in part related to host immune system differences (Longo et al., 2015). Furthermore, skin restructuring may include changes in innate immune system function, skin pH or other components of the mucosal layer, similar to changes at metamorphosis (Kueneman et al., 2015), which have a role in structuring host microbiota (Franzenburg et al., 2013; Küng et al., 2014; Colombo et al., 2015).

The influence of skin morphology in temporal variation of skin microbiota is further exemplified by the distinct communities characterizing terrestrial and aquatic newts. Terrestrial phase skin bacterial communities were enriched for 12 OTUs consistently across both Kleiwiesen and Elm. Interestingly, Enterobacteriaceae was more abundant on terrestrial phase newts, and also increased on aquatic individuals at later time-points. As newts prepare for the transition to terrestrial life their skin structure begins to change (Perrotta et al., 2012), and this change could drive shifts in community members. Similarly, in humans, temporal shifts in skin, oral and gut microbial communities tend to be associated with transitional events (for example, skin oil production, tooth eruption, milk-to-solid food) that may impose environmental filters that exert a selective effect (Marsh, 2000; Robinson et al., 2010; Costello et al., 2012).

In this context of temporal changes in host-associated bacterial communities, we hypothesized that such changes would be coupled with significant variation in predicted Bd-inhibitory function. Hosts may temporally lose important protective bacterial taxa, which could have drastic consequences with respect to disease. Furthermore, the aquatic-to-terrestrial transition potentially could result in dysbiotic transitional states as has been hypothesized with sloughing (Cramp et al., 2014) and metamorphosis (Kueneman et al., 2015). We used a bioinformatics approach to identify OTUs that can ‘potentially’ inhibit Bd (Kueneman et al., 2015, 2016). Given that we found this pathogen on newts and that it has measurable sublethal effects on a related European newt species (Cheatsazan et al., 2013), it is likely exerting selective pressures on the studied hosts and their microbiota. Our results indicate that the proportion of predicted Bd-inhibitory reads did not vary temporally for two of three newt species, and aquatic and terrestrial individuals did not differ, suggesting that this Bd-inhibitory function was largely maintained despite structural variation. It is a common view that changes in microbial composition are linked to alterations in functional capabilities (Strickland et al., 2009; Shade et al., 2013). However, more and more studies provide evidence that structure and function can be de-coupled (Burke et al., 2011; Purahong et al., 2014; Louca et al., 2016). Stability of predicted Bd-inhibitory function herein appears to be associated with both constancy of particular OTUs and replacement of function by different OTUs. Functional redundancy among bacterial OTUs can make this possible (Allison and Martiny, 2006; Shade et al., 2012). In fact, Burke et al. (2011) proposed that microbial communities on algae assemble based on functional genes following a competitive lottery mechanism. More specifically, this model suggests bacteria with similar ecological properties are able to occupy the same niche but the particular taxon occupying that space is stochastically recruited. Perhaps in the newt system, microbes are assembling in a manner similar to the model of Burke et al. (2011). As the environmental reservoir shifts temporally and the newt skin environment changes, it recruits different taxa, independent of phylogenetic identity, which are best able to reside within existing physiochemical parameters of the skin; at the same time, selective pressure on the host may lead to evolution of a mucosal environment making it particularly suitable for some protective bacteria (that is, fungal-inhibiting taxa), thereby explaining maintenance of Bd-inhibitory function amidst temporal phylogenetic variation in the underlying OTUs within this study. If protection provided by these bacteria can persist temporally, such protection may be able to fill the gaps when host-mediated defenses (for example, antimicrobial peptides) may be reduced (Woodhams et al., 2012; Holden et al., 2015; Kueneman et al., 2015). It is important to acknowledge that our functional inference is from predictions via a bioinformatic approach and therefore depend on assumptions of functional equivalence of 16S gene matches. Our functional predictions serve as a preliminary indication that function may be maintained amidst structural variation and require further testing via metagenomic or metatranscriptomic approaches.

The results of our study support our first hypothesis that newt bacterial communities would exhibit strong temporal variation with respect to their taxonomic structure within the aquatic phase, as well as across the aquatic-to-terrestrial transition. However, the relative stability with respect to their predicted Bd-inhibitory function fails to support our second hypothesis that structural and functional variation would be linked. In the context of disease dynamics, these data suggest that protection from disease may be maintained despite taxonomic variability in microbiota, highlighting the potential un-coupling of community structure and function (Purahong et al., 2014) and complexity of host microbial community dynamics. Owing to the importance of beneficial microbes in pathogen defense, maintenance of protective microbial function through time is likely essential for continuous defense against pathogens (Rosenberg et al., 2007; Bletz et al., 2013; Fraune et al., 2014). Perhaps this maintenance of function allows some amphibian species, like those studied here, to resist cutaneous fungal pathogens. For salamandrid newts and North American salamanders, in particular, continuous protection from the emerging pathogen, Bsal, (Martel et al., 2014; Spitzen-van der Sluijs et al., 2016) may be critical for population survival. Understanding dynamics of amphibian skin microbiota can facilitate development of probiotic bioaugmentation strategies that can afford protection for these threatened vertebrates. Future studies using metagenomics and metatranscriptomics will further elucidate our understanding of host–microbe interactions and the structure–function relationship within amphibian skin microbiomes, as well as other wildlife hosts threatened by disease.

Data accessibility

Sequence data are deposited in the Sequence Read Database (SRP074714; Bioproject PRJNA320969).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the conservation authorities of Helmstedt and Braunschweig for research permits. Special thanks are due to Uwe Kirchberger for continued assistance. This study was supported by a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) to MV (VE247/9-1), and by a fellowship of the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) to MCB. We are indebted to Meike Kondermann for her assistance with laboratory work and Joana Sabino Pinto for performing qPCR reactions.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Allison SD, Martiny JBH. (2006) Resistance, resilience, and redundancy in microbial communities. In: Avise JC, Hubbel SP, Ayala FJ (eds). Vol. II. In the Light of Evolution. The National Academies Press: Washington DC, USA, pp 11512–11519. [Google Scholar]

- Altizer S, Dobson A, Hosseini P, Hudson P, Pascual M, Rohani P. (2006). Seasonality and the dynamics of infectious diseases. Ecol Lett 9: 467–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antwis RE, Preziosi RF, Harrison XA, Garner TW. (2015). Amphibian symbiotic bacteria do not show universal ability to inhibit growth of the global pandemic lineage of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Appl Environ Microbiol 81: 3706–3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker M, Walker S. (2015). Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Becker MH, Brucker RM, Schwantes CR, Harris RN, Minbiole KPC. (2009). The bacterially produced metabolite violacein is associated with survival of amphibians infected with a lethal fungus. Appl Environ Microbiol 75: 6635–6638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker MH, Harris RN. (2010). Cutaneous bacteria of the redback salamander prevent morbidity associated with a lethal disease. PLoS One 5: e10957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker MH, Walke JB, Cikanek S, Savage AE, Mattheus N, Santiago CN et al. (2015). Composition of symbiotic bacteria predicts survival in Panamanian golden frogs infected with a lethal fungus. Proc R Soc B 282: 20142881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belden LK, Hughey MC, Rebollar EA, Umile TP, Loftus SC, Burzynski EA et al. (2015). Panamanian frog species host unique skin bacterial communities. Front Microbiol 6: 1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger L, Speare R, Daszak P, Green DE, Cunningham AA, Goggin CL et al. (1998). Chytridiomycosis causes amphibian mortality associated with population declines in the rain forests of Australia and Central America. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 9031–9036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bletz MC, Loudon AH, Becker MH, Bell SC, Woodhams DC, Minbiole KPC et al. (2013). Mitigating amphibian chytridiomycosis with bioaugmentation: characteristics of effective probiotics and strategies for their selection and use. Ecol Lett 16: 807–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blooi M, Pasmans F, Longcore JE, Spitzen-Van Der Sluijs A, Vercammen F, Martel A. (2013). Duplex real-time PCR for rapid simultaneous detection of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans in amphibian samples. J Clin Microbiol 51: 4173–4177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokulich NA, Subramanian S, Faith JJ, Gevers D, Gordon I, Knight R et al. (2013). Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat Methods 10: 57–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke C, Steinberg P, Rusch DB, Kjelleberg S, Thomas T. (2011). Bacterial community assembly based on functional genes rather than species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 14288–14293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante HM, Livo LJ, Carey C. (2010). Effects of temperature and hydric environment on survival of the Panamanian golden frog infected with a pathogenic chytrid fungus. Integr Zool 5: 143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK et al. (2010). QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7: 335–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Costello EK, Berg-Lyons D, Gonzalez A, Stombaugh J et al. (2011). Moving pictures of the human microbiome. Genome Biol 12: R50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrino-Kyker SR, Swanson AK. (2008). Temporal and spatial patterns of eukaryotic and bacterial communities found in vernal pools. Appl Environ Microbiol 74: 2554–2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheatsazan H, de Almedia APLG, Russell AF, Bonneaud C. (2013). Experimental evidence for a cost of resistance to the fungal pathogen, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, for the palmate newt, Lissotriton helveticus. BMC Ecol 13: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H, Pamp J, Hill JA, Surana NK, Edelman SM, Troy EB et al. (2012). Gut immune maturation depends on colonization with a host-specific microbiota. Cell 149: 1578–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke KR, Gorley RN. (2015). PRIMER v7: User Manual/Tutorial. PRIMER-E, Plymouth, p296.

- Colombo BM, Scalvenzi T, Benlamara S, Pollet N. (2015). Microbiota and mucosal immunity in amphibians. Front Immunol 6: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EK, Lauber CL, Hamady M, Fierer N, Gordon JI, Knight R. (2009). Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science 326: 1694–1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EK, Stagaman K, Dethlefsen L, Bohannan BJM, Relman DA. (2012). The application of ecological theory toward an understanding of the human microbiome. Science 336: 1255–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramp RL, Mcphee RK, Meyer EA, Ohmer ME, Franklin CE. (2014). First line of defence: the role of sloughing in the regulation of cutaneous microbes in frogs. Conserv Biol 2: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump BC, Hobbie JE. (2005). Synchrony and seasonality in bacterioplankton communities of two temperate rivers. Limnol Oceanogr 50: 1718–1729. [Google Scholar]

- Daskin JH, Bell SC, Schwarzkopf L, Alford RA. (2014). Cool temperatures reduce antifungal activity of symbiotic bacteria of threatened amphibians – Implications for disease management and patterns of decline. PLoS One 9: e100378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dethlefsen L, McFall-Ngai M, Relman DA. (2007). An ecological and evolutionary perspective on human–microbe mutualism and disease. Nature 449: 811–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas B, Martin M, Ben B, Steve W. (2015). Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J Stat Softw 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Drechsler A, Bock D, Ortmann D, Steinfartz S. (2010). Ortmann’s funnel trap – a highly efficient tool for monitoring amphibian species. Herpetol Notes 3: 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Eberl G. (2010). A new vision of immunity: homeostasis of the superorganism. Mucosal Immunol 3: 450–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel P, Moran NA. (2013). The gut microbiota of insects-diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol Rev 37: 699–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierer N, Ferrenberg S, Flores GE, González A, Kueneman J, Legg T et al. (2012). From animalicules to an ecosystem: application of ecological concepts to the human microbiome. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 43: 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick BM, Allison AL. (2014). Similarity and differentiation between bacteria associated with skin of salamanders (Plethodon jordani and free-living assemblages. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 88: 482–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flechas SV, Sarmiento C, Cardenas ME, Medina EM, Restrepo S, Amezquita A. (2012). Surviving chytridiomycosis: differential anti-Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis activity in bacterial isolates from three lowland species of Atelopus. PLoS One 7: e44832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzenburg S, Walter J, Künzel S, Wang J, Baines JF, Bosch TCG et al. (2013). Distinct antimicrobial peptide expression determines host species-specific bacterial associations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: E3730–E3738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraune S, Anton-Erxleben F, Augustin R, Franzenburg S, Knop M, Schröder K et al. (2014). Bacteria-bacteria interactions within the microbiota of the ancestral metazoan Hydra contribute to fungal resistance. ISME J 9: 1543–1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frossard A, Gerull L, Mutz M, Gessner MO. (2011). Disconnect of microbial structure and function: enzyme activities and bacterial communities in nascent stream corridors. ISME J 6: 680–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukami T, Ian A, Wilkie JP, Paulus C, Park D, Roberts A et al. (2010). Assembly history dictates ecosystem functioning: evidence from wood decomposer communities. Ecology 13: 675–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo RL, Hooper LV. (2012). Epithelial antimicrobial defence of the skin and intestine. Nat Rev Immunol 12: 503–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassly NC, Fraser C. (2006). Seasonal infectious disease epidemiology. Proc Biol Sci 273: 2541–2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grice EA, Segre JA. (2011). The skin microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol 9: 244–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RN, Brucker RM, Walke JB, Becker MH, Schwantes CR, Flaherty DC et al. (2009). Skin microbes on frogs prevent morbidity and mortality caused by a lethal skin fungus. ISME J 3: 818–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RN, James TY, Lauer A, Simon MA, Patel A. (2006). Amphibian pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis is inhibited by the cutaneous bacteria of amphibian species. Ecohealth 3: 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Harris RN, Lauer A, Simon MA, Banning JL, Alford RA. (2009. b). Addition of antifungal skin bacteria to salamanders ameliorates the effects of chytridiomycosis. Dis Aquat Organ 83: 11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden WM, Hanlon SM, Woodhams DC, Chappell TM, Wells HL, Glisson SM et al. (2015). Skin bacteria provide early protection for newly metamorphosed southern leopard frogs (Rana sphenocephala against the frog-killing fungus, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Biol Conserv 187: 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Jones SE, Cadkin TA, Newton RJ, Mcmahon KD, Lynch RC. (2012). Spatial and temporal scales of aquatic bacterial beta diversity. Front Microbiol 3: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser C, Koranda M, Kitzler B, Fuchslueger L, Schnecker J, Schweiger P et al. (2010). Below ground carbon allocation by trees drives seasonal patterns of extracellular enzyme activities by altering microbial community composition in a beech forest soil. New Phytol 187: 843–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent AD, Yannarell AC, Rusak JA, Triplett EW, Mcmahon KD. (2007). Synchrony in aquatic microbial community dynamics. ISME J 1: 38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosravi A, Mazmanian SK. (2013). Disruption of the gut microbiome as a risk factor for microbial infections. Curr Opin Microbiol 16: 221–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney VC, Heemeyer JL, Pessier AP, Lannoo MJ. (2011). Seasonal pattern of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis infection and mortality in Lithobates areolatus: affirmation of Vredenburg’s ‘10,000 zoospore rule’. PLoS One 6: e16708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl KD, Yahn J. (2016). Effects of environmental temperature on the gut microbial communities of tadpoles. Environ Microbiol 18: 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozich JJ, Westcott SL, Baxter NT, Highlander SK, Schloss PD. (2013). Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the Miseq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl Environ Microbiol 79: 5112–5120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krediet CJ, Ritchie KB, Alagely A, Teplitski M. (2013). Members of native coral microbiota inhibit glycosidases and thwart colonization of coral mucus by an opportunistic pathogen. ISME J 7: 980–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kueneman JG, Parfrey LW, Woodhams DC, Archer HM, Knight R, McKenzie VJ. (2014). The amphibian skin-associated microbiome across species, space and life history stages. Mol Ecol 23: 1238–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kueneman JG, Woodhams DC, Harris R, Archer HM, Knight R, Mckenzie VJ. (2016). Probiotic treatment restores protection against lethal fungal infection lost during amphibian captivity. Proc Biol Sci 283: 20161553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kueneman JG, Woodhams DC, Van Treuren W, Archer HM, Knight R, McKenzie VJ. (2015). Inhibitory bacteria reduce fungi on early life stages of endangered Colorado boreal toads (Anaxyrus boreas. ISME J 10: 934–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küng D, Bigler L, Davis LR, Gratwicke B, Griffith E, Woodhams DC. (2014). Stability of microbiota facilitated by host immune regulation: informing probiotic strategies to manage amphibian disease. PLoS One 9: e87101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam BA, Walke JB, Vredenburg VT, Harris RN. (2010). Proportion of individuals with anti-Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis skin bacteria is associated with population persistence in the frog Rana muscosa. Biol Conserv 143: 529–531. [Google Scholar]

- Langwig KE, Frick WF, Reynolds R, Parise KL, Drees KP, Hoyt JR et al. (2015). Host and pathogen ecology drive the seasonal dynamics of a fungal diseas, white-nose syndrome. Proc R Soc B 282: 20142335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lips KR, Brem F, Brenes R, Reeve JD, Alford RA, Voyles J et al. (2006). Emerging infectious disease and the loss of biodiversity in a Neotropical amphibian community. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 3165–3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo AV, Burrowes Pa, Joglar RL. (2010). Seasonality of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis infection in direct-developing frogs suggests a mechanism for persistence. Dis Aquat Organ 92: 253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo AV, Savage AE, Hewson I, Zamudio KR. (2015). Seasonal and ontogenetic variation of skin microbial communities and relationships to natural disease dynamics in declining amphibians. R Soc Open Sci 2: 140377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louca S, Jacques SMS, Pires APF, Leal JS, Srivastava DS, Parfrey LW et al. (2016). High taxonomic variability despite stable functional structure across microbial communities. Nat Ecol Evol 1: 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loudon AH, Woodhams DC, Parfrey LW, Archer HM, Knight R, McKenzie V et al. (2014). Microbial community dynamics and effect of environmental microbial reservoirs on red-backed salamanders (Plethodon cinereus. ISME J 8: 830–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh PD. (2000). Role of the oral microflora in health. Microb Ecol Health Dis 12: 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Martel A, Blooi M, Adriaensen C, Rooij P, Van, Beukema W, Fisher MC et al. (2014). Recent introduction of a chytrid fungus endangers western Palearctic salamanders. Science 6209: 630–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel A, Spitzen-van der Sluijs A, Blooi M, Bert W, Ducatelle R, Fisher MC et al. (2013). Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans sp. nov. causes lethal chytridiomycosis in amphibians. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 15325–15329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie VJ, Bowers RM, Fierer N, Knight R, Lauber CL. (2012). Co-habiting amphibian species harbor unique skin bacterial communities in wild populations. ISME J 6: 588–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer EA, Cramp RL, Bernal MH, Franklin CE. (2012). Changes in cutaneous microbial abundance with sloughing: possible implications for infection and disease in amphibians. Dis Aquat Organ 101: 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemergut DR, Schmidt SK, Fukami T, O’Neill SP, Bilinski TM, Stanish LF et al. (2013). Patterns and processes of microbial community assembly. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77: 342–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotta I, Sperone E, Bernabo I, Tripepi S, Brunelli E. (2012). The shift from aquatic to terrestrial phenotype in Lissotriton italicus: larval and adult remodelling of the skin. Zoology 115: 170–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillott AD, Grogan LF, Cashins SD, McDonald KR, Berger L, Skerratt LF. (2013). Chytridiomycosis and seasonal mortality of tropical stream-associated frogs 15 years after introduction of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Conserv Biol 27: 1058–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portillo MC, Anderson SP, Fierer N. (2012). Temporal variability in the diversity and composition of stream bacterioplankton communities. Environ Microbiol 14: 2417–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purahong W, Schloter M, Pecyna MJ, Kapturska D, Daumlich V, Mital S et al. (2014). Uncoupling of microbial community structure and function in decomposing litter across beech forest ecosystems in Central Europe. Sci Rep 4: 7014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. URL. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. (2004). Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell 118: 229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebollar EA, Hughey MC, Medina D, Harris RN, Ibáñez R, Belden LK. (2016). Skin bacterial diversity of Panamanian frogs is associated with host susceptibility and presence of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. ISME J 10: 1682–1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CJ, Bohannan BJM, Young VB. (2010). From structure to function: the ecology of host-associated microbial communities. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 74: 453–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohr JR, Raffel TR, Romansic JM, McCallum H, Hudson PJ. (2008). Evaluating the links between climate, disease spread, and amphibian declines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 17436–17441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins-Smith LA. (2009). The role of amphibian antimicrobial peptides in protection of amphibians from pathogens linked to global amphibian declines. Biochim Biophys Acta 1788: 1593–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg E, Koren O, Reshef L, Efrony R, Zilber-Rosenberg I. (2007). The role of microorganisms in coral health, disease and evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol 5: 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal M, Goldberg D, Aiello A, Larson E, Foxman B. (2011). Skin microbiota: microbial community structure and its potential association with health and disease. Infect Genet Evol 11: 839–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez E, Bletz MC, Dunsch L, Bhuju S, Geffers R, Jarek M et al. (2016). Cutaneous bacterial communities of a poisonous salamander: a perspective from life stages, body parts and environmental conditions. Microb Ecol 73: 455–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage AE, Sredl MJ, Zamudio KR. (2011). Disease dynamics vary spatially and temporally in a North American amphibian. Biol Conserv 144: 1910–1915. [Google Scholar]

- Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS et al. (2011). Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol 12: R60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shade A, Caporaso JG, Handelsman J, Knight R, Fierer N. (2013). A meta-analysis of changes in bacterial and archaeal communities with time. ISME J 7: 1493–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shade A, Peter H, Allison SD, Baho DL, Berga M, Burgmann H et al. (2012). Fundamentals of microbial community resistance and resilience. Front Microbiol 3: 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singmann H, Bolker B, Westfall J. (2015). afex: Analysis of Factorial Experiments. R package version 0.13-145.

- Spitzen-van der Sluijs A, Martel A, Asselberghs J, Bales EK, Beukema W, Bletz MC et al. (2016). Expanding distribution of lethal amphibian fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans in Europe. Emerg Infect Dis 22: 1286–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stappenbeck TS, Hooper LV, Gordon JI. (2002). Developmental regulation of intestinal angiogenesis by indigenous microbes via Paneth cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 15451–15455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecher B, Hardt WD. (2008). The role of microbiota in infectious disease. Trends Microbiol 16: 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecher B, Robbiani R, Walker AW, Westendorf AM, Barthel M, Kremer M et al. (2007). Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium exploits inflammation to compete with the intestinal microbiota. PLoS Biol 5: 2177–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland MS, Lauber CL, Fierer N, Bradford MA. (2009). Testing the functional significance of microbial community composition. Ecology 90: 441–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vredenburg VT, Briggs CJ, Harris RN. (2011) Host-pathogen dynamics of amphibian chytridiomycosis: the role of the skin microbiome in health and disease. In: Olson L, Choffnes E, Relman D, Pray L. (eds). Fungal Diseases: An Emerging Threat to Human, Animal, and Plant Health. National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, pp 342–355. [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop MP, Firestone MK. (2006). Response of microbial community composition and function to soil climate change. Microb Ecol 52: 716–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walke JB, Becker MH, Loftus SC, House LL, Cormier G, Jensen RV et al. (2014). Amphibian skin may select for rare environmental microbes. ISME J 8: 2207–2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter J, Ley R. (2011). The human gut microbiome: ecology and recent evolutionary changes. Annu Rev Microbiol 65: 411–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhams DC, Alford RA, Antwis RE, Archer HM, Becker MH, Belden LK et al. (2015). Antifungual isolates database of amphibian skin-associated bacteria and function against emerging fungal pathogens. Ecology 96: 595. [Google Scholar]

- Woodhams DC, Bigler L, Marschang R. (2012). Tolerance of fungal infection in European water frogs exposed to Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis after experimental reduction of innate immune defenses. BMC Vet Res 8: 197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhams DC, Brandt H, Baumgartner S, Kielgast J, Küpfer E, Tobler U et al. (2014). Interacting symbionts and immunity in the amphibian skin mucosome predict disease risk and probiotic effectiveness. PLoS One 9: e96375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhams DC, Vredenburg VT, Simon M-A, Billheimer D, Shakhtour B, Shyr Y et al. (2007). Symbiotic bacteria contribute to innate immune defenses of the threatened mountain yellow-legged frog Rana muscosa. Biol Conserv 138: 390–398. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data are deposited in the Sequence Read Database (SRP074714; Bioproject PRJNA320969).