Abstract

The Heimlich manoeuvre is a well-known intervention for the management of choking due to foreign body airway occlusion, but the evidence base for guidance on this topic is limited and guidelines differ. We measured pressures during abdominal thrusts in healthy volunteers. The angle at which thrusts were performed (upthrust vs circumferential) did not affect intrathoracic pressure. Self-administered abdominal thrusts produced similar pressures to those performed by another person. Chair thrusts, where the subject pushed their upper abdomen against a chair back, produced higher pressures than other manoeuvres. Both approaches should be included in basic life support teaching.

Keywords: Respiratory Measurement

Background

Foreign body airway obstruction (FBAO) is a common cause of death, particularly in older people. The National Safety Council USA reports that FBAO is the fourth leading cause of unintentional injury death, with 4864 reported deaths in 2013.1 The ‘Heimlich’ manoeuvre is a technique for expelling an obstructing food bolus where a first-aider places their arms round the subject from behind and delivers a sharp inward and upward thrust to the abdomen below the rib cage. Heimlich described 162 cases where life was saved following successful administration of abdominal thrusts.2

European Resuscitation Council3 guidance for treatment of FBAO in conscious adults is a combination of back blows and abdominal thrusts with no preference on order. The Australian and New Zealand Resuscitation Councils recommend back blows and chest thrusts for the management of FBAO in conscious adults, but advise against abdominal thrusts, citing concern about complications.4

External pressure on the abdomen should be transmitted through the diaphragm regardless of where it is applied, so there is no theoretical reason why force needs to be directed upwards. Motivated in part by three cases of near death from choking involving UK chest physicians (see online supplement), we describe experiments to address these two questions.

thoraxjnl-2016-209540supp001.pdf (375.3KB, pdf)

Methods

Detailed methods are available in the online supplement. Briefly, different expulsive manoeuvres (see box 1) were performed on and by four consenting adult physiology researchers median (range): age 56.5 (46, 74) years and body mass index (BMI) 25.9 (25, 26) kg/m2. Oesophageal and gastric balloon catheters were placed to record pressures generated. Detailed statistical analysis is available in the online supplement.

Box 1. Description of manoeuvres.

Circumferential ‘horizontal’ abdominal thrust

The operator stands behind the participant, grasps their fists together and places thumb side of the fist over the fleshy part of the abdomen above the navel. The operator pulls sharply backwards starting with medium force and progressively increasing force, until the maximum pressure that the subject feels is acceptable is achieved.

Heimlich manoeuvre

The same procedure but with an upward direction of force.

Auto ‘upthrust’ abdominal thrust

The participant positions their own hands in the standard position for the abdominal manoeuvre and performs thrusts increasing to the maximal force they can tolerate.

Chair thrust

The participant positions themselves above a high backed chair, with the chair back positioned below the upper half of the abdomen, below the ribcage. Using gravity, bodyweight and arms for additional force, the participant allows the back of the chair to thrust up into their abdomen (see figure 1).

Volitional maximal cough and sniff pressures

The participant performed repeated maximal volitional cough and sniff manoeuvres.

All manoeuvres were performed after exhalation to the end of a normal breath (at functional residual capacity) with mouth and glottis closed and a nose clip in situ.

Figure 1.

One of the authors (MH) performing a chair thrust on himself (see also online supplementary video).

thoraxjnl-2016-209540supp002.mp4 (17.8MB, mp4)

Results

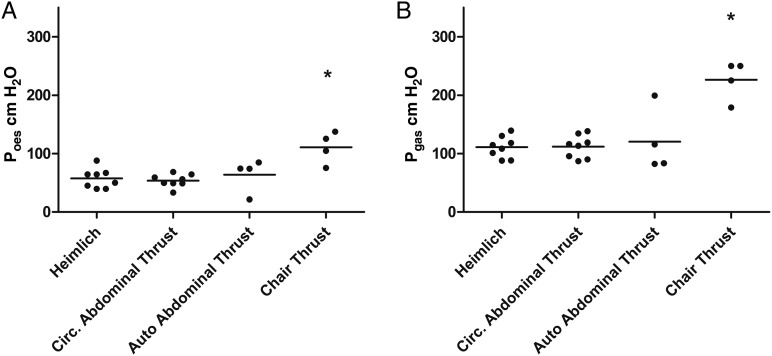

Maximum peak oesophageal (Poes) and gastric (Pgas) pressures were similar for the different abdominal thrusts when performed by the experimenters or by the subjects on themselves (see figure 2 and online supplementary table E1). For the upthrust Heimlich manoeuvre, Poes was 57±17 cm H2O and for the circumferential abdominal thrust 53±11 cm H2O (p=0.7). The chair thrust generated a significantly higher Poes than both; 115±27 cm H2O (p=0.008 compared with Heimlich).

Figure 2.

Oesophageal and gastric pressure responses to expulsive manoeuvres. All statistical tests Mann-Whitney test. *Results are statistically significant (p<0.05). (A) Maximal oesophageal pressures (Poes) achieved by expulsive manoeuvres. Pressure was significantly higher for chair thrust (p=0.008) but did not differ between conventional upthrust Heimlich, circumferential abdominal thrust or self-administered autoabdominal thrust. (B) Maximal gastric pressures were significantly higher in chair thrust compared with Heimlich manoeuvres (p=0.004). The outlier autoabdominal thrust data point in (B) corresponds to the participant (MH) who had performed an abdominal thrust on himself described in case 2 (see online supplement).

In one participant, three further manoeuvres were performed. The Poes generated by back slaps (7 cm H2O) and chest compressions when supine (position taken as for CPR) (42 cm H2O) were lower than both the Heimlich manoeuvre (64 cm H2O) and cough (179 cm H2O) in that subject. Poes from supine abdominal compressions was 86 cm H2O, comparable to abdominal thrusts when upright.

Discussion

Abdominal thrusts caused a sharp rise in abdominal and thoracic pressures, exceeding or equal to those produced by these and alternative manoeuvres in previous studies.5–8

In 12 supine cadavers, mean airway pressure was 40.8 cm H2O for chest and 26.4 cm H2O for abdominal thrusts.5 In six anaesthetised and intubated healthy adult male volunteers airway pressures from abdominal thrusts, low-chest thrusts and mid-chest thrusts in the horizontal lateral and sitting positions were compared.6 Low-chest thrusts in the horizontal lateral position (34.0 cm H2O) and mid-chest thrusts in the sitting position (46.2 cm H2O) produced the highest pressures. In eight intubated and anaesthetised pigs, anterior chest thrusts and Heimlich manoeuvres, both performed in a seated position, produced airway pressures of 6.5 and 13.8 cm H2O, respectively, with lateral chest thrusts in the side-lying position producing 18.0 cm H2O.7 Day et al8 compared alveolar pressure change for back blows (17.7 cm H2O) and the Heimlich manoeuvre (36.7 cm H2O).

An upward thrust may be more likely to cause injury to the ribcage or other organs and the person performing it may be inhibited by this possibility. Given the similar pressures generated by circumferential abdominal thrusts, we recommend that the manoeuvre should be performed by inward thrust over the fleshy part of the abdomen, around the level of the navel. This is important information for first aid providers with mismatched height to victim; a smaller individual can perform the circumferential abdominal thrust and produce the same intrathoracic pressure as the Heimlich manoeuvre that requires upthrust.

Australian and New Zealand ALS guidance does not recommend abdominal thrusts.4 Studies on pigs, cadavers or anaesthetised subjects are unlikely to be representative of the situation and lung volumes in an upright, conscious choking individual. In our study, manoeuvres were all performed with the subjects at functional residual capacity, which may be more representative of the situation in an emergency. Given our data, we suggest that these guidelines should be amended. Concern about possible risk needs to be balanced against the almost certain risk of death if obstruction persists and the further reduction in risk if a circumferential approach is used.

Self-administered abdominal thrusts were as effective as operator-delivered thrusts and indeed they had been used successfully in two of our cases (online). Repeated manoeuvres can be performed quickly and effectively without relying on an external operator. People choking may be encouraged to try this before a rescuer makes an attempt. Self-administering the manoeuvre is also a clear signal to rescuers (compared with clutching one's throat, which might be misinterpreted as distress due to another cause such as a heart attack). A novel finding is that self-administered thrusts over the back of a chair generated greater pressures than operator-delivered thrusts or self-administered ones. Most food is consumed seated, so there is likely to be a chair available when choking occurs.

Obesity

No obese subjects were included in this study, median BMI 25.9 (25–26) kg/m.2 Obesity may affect abdominal thrust outcome as anatomical landmarks for hand positioning may be variable and add to the difficulty of performing the manoeuvre around an increased abdominal circumference. A higher percentage of abdominal adipose tissue may have a dissipating effect on the force applied with abdominal thrust manoeuvres and therefore lessen their effectiveness.

Conclusion

The key to diagnosing complete airway obstruction is a conscious subject, in the process of eating, who is unable to breathe at all, nor to speak. Autoadministered thrusts appear as physiologically effective as first-aider-administered ones to generate expulsive intrathoracic pressures, and chair thrusts appear to be the most physiologically effective. We advise that everyone with complete airway obstruction should, in the first instance, either autoadminister abdominal thrusts or perform a chair thrust. The various manoeuvres should be more widely taught in schools, first aid courses, to staff in restaurants and publicised as widely as possible. We would like to see suitable notices in eating places.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the individual involved in case 1 for permission to include a description account of his choking and John Moore-Gillon for permission to include his own account of his experience (case 3 online).

Twitter: Follow Matthew Pavitt @DrMattPav; Nicholas Hopkinson @COPDdoc

Contributors: NSH, MG, MH and MIP conceived the study. MG, MP, LS, MA and NSH performed experiments and collected data. MP and LS analysed the results and produced the first draft of the paper to which all authors contributed, and all authors have approved the final version.

Funding: The study was supported by the NIHR Respiratory BRU at Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust and Imperial College, London, who part fund MIP's salary.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health. NSH affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Imperial College Joint Research Office and Health Research Authority.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Requests for anonymised individual patient data can be made to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.National Safety Council. Choking prevention and rescue tips. 2016. http://www.nsc.org/learn/safety-knowledge/Pages/safety-at-home-choking.aspx (accessed 6 Oct 2016).

- 2.Heimlich HJ, Hoffmann KA, Canestri FR. Food-choking and drowning deaths prevented by external subdiaphragmatic compression. Physiological basis. Ann Thorac Surg 1975;20:188–95. 10.1016/S0003-4975(10)63874-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perkins GD, Handley AJ, Koster RW, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015: Section 2. Adult basic life support and automated external defibrillation. Resuscitation 2015;95:81–99. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Australian and New Zealand Resuscitation Councils. ANZCOR Guideline 4—Airway. 2016. https://resus.org.au/guidelines/ (accessed 6 Oct 2016).

- 5.Langhelle A, Sunde K, Wik L, et al. Airway pressure with chest compressions versus Heimlich manoeuvre in recently dead adults with complete airway obstruction. Resuscitation 2000;44:105–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guildner CW, Williams D, Subitch T. Airway obstructed by foreign material: the Heimlich maneuver. JACEP 1976;5:675–7. 10.1016/S0361-1124(76)80099-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lippmann J, Taylor DM, Slocombe R, et al. Lateral versus anterior thoracic thrusts in the generation of airway pressure in anaesthetised pigs. Resuscitation 2013;84:515–9. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Day RL, Crelin ES, DuBois AB. Choking: the Heimlich abdominal thrust vs back blows: an approach to measurement of inertial and aerodynamic forces. Pediatrics 1982;70:113–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

thoraxjnl-2016-209540supp001.pdf (375.3KB, pdf)

thoraxjnl-2016-209540supp002.mp4 (17.8MB, mp4)