ABSTRACT

Chronic airway infections by the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa are a major cause of mortality in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients. Although this bacterium has been extensively studied for its virulence determinants, biofilm growth, and immune evasion mechanisms, comparatively little is known about the nutrient sources that sustain its growth in vivo. Respiratory mucins represent a potentially abundant bioavailable nutrient source, although we have recently shown that canonical pathogens inefficiently use these host glycoproteins as a growth substrate. However, given that P. aeruginosa, particularly in its biofilm mode of growth, is thought to grow slowly in vivo, the inefficient use of mucin glycoproteins may be relevant to its persistence within the CF airways. To this end, we used whole-genome fitness analysis, combining transposon mutagenesis with high-throughput sequencing, to identify genetic determinants required for P. aeruginosa growth using intact purified mucins as a sole carbon source. Our analysis reveals a biphasic growth phenotype, during which the glyoxylate pathway and amino acid biosynthetic machinery are required for mucin utilization. Secondary analyses confirmed the simultaneous liberation and consumption of acetate during mucin degradation and revealed a central role for the extracellular proteases LasB and AprA. Together, these studies describe a molecular basis for mucin-based nutrient acquisition by P. aeruginosa and reveal a host-pathogen dynamic that may contribute to its persistence within the CF airways.

KEYWORDS: cystic fibrosis, glyoxylate pathway, mucin, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, TnSeq

INTRODUCTION

Cystic fibrosis (CF), a common and lethal autosomal recessive disease, results from mutations in the gene encoding the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein (1). Impaired CFTR function leads to abnormal transepithelial ion transport and a thickened, dehydrated mucus layer that overlays the epithelium of several organs, including the lungs (2, 3). Within the airways, defective mucociliary clearance facilitates chronic colonization by a complex bacterial community, and the ensuing inflammatory response leads to bronchiectasis, progressive lung damage, and eventual respiratory failure in a majority of CF patients (2). Despite the recent surge in studies describing a polymicrobial etiology of CF, Pseudomonas aeruginosa continues to be widely recognized as the primary driver of disease progression (4). This opportunistic pathogen can reach densities of 107 to 109 CFU/g of sputum, particularly in late stages of disease, suggesting that the mucus environment of the lower airways provides the bacterium an ideal growth environment (5, 6). A deeper understanding of this milieu, and its ability to sustain P. aeruginosa growth in vivo is critically important for improved disease management.

The mucosal layer covering the respiratory epithelium is a complex mixture of water, salts, protein, lipid, nucleic acids, mucins, and lower molecular mass glycoproteins (7). The gel-forming mucins MUC5B and MUC5AC are highly glycosylated (70 to 80% by weight) polypeptides that form a cross-linked, hydrated gel and comprise the major macromolecular constituents of the mucus layer. These mucins protect the underlying airway mucosa since they provide a first line of innate immune defense against pathogens and environmental toxins (8). In CF, however, the hypersecretion of mucins, their increased viscosity, and impaired clearance compromise their role in host defense and are thought to contribute to disease pathophysiology (9–12). For example, P. aeruginosa has mucin-specific adhesins that mediate surface attachment by recognizing sialic acid and N-acetylglucosamine residues (13–15). Moreover, studies have shown that CF mucins are bound more efficiently by P. aeruginosa relative to non-CF mucins (15). Various reports have also described the role of mucins in stimulating bacterial surface motility, biofilm and aggregate formation, and the transition between biofilm and free-swimming states (16–20). In addition, the direct interaction of mucins with respiratory pathogens is thought to serve as a signaling event for the induction of various virulence factors (21).

Mucins also represent an abundant, host-derived nutrient reservoir for pathogens to utilize. In fact, all mucosal sites throughout the human body harbor both commensal and pathogenic organisms that possess mucin-degrading enzymes capable of deriving nutrients from host (22–24). Indeed, several studies have described the degradation and utilization of mucins by CF-associated microbiota (25–29). For example, multiple studies have shown that P. aeruginosa and other pathogens (e.g., Burkholderia cepacia complex [BCC]) harbor mucin sulfatase activity capable of utilizing sialylated mucin oligosaccharides as a source of sulfur (26, 28). Others have shown that BCC isolates possess mucinase activity that can sustain pathogen growth using mucins as a sole carbon source (29). These studies emphasize the potential importance of mucins as a growth substrate for the initiation and maintenance of CF infections in vivo.

To investigate respiratory mucin-bacterial interactions in further detail, artificial sputum media (ASM) are commonly used to mimic the in vivo nutritional environment of the diseased airways. Among its constituents, porcine gastric mucin (PGM) is incorporated as a model carbon substrate because of its cost, ease of preparation, and similarity to human tracheal mucins in carbohydrate composition (30, 31). Use of PGM-based “sputum” media has generated insight into P. aeruginosa physiology under conditions relevant to the CF airways. For example, Sriramulu et al. (32) demonstrated that when PGMs are omitted from ASM, P. aeruginosa growth is limited, which implicated mucins as an important carbon source. Others have shown that isolates grown on PGM-based ASM media yield similar P. aeruginosa transcriptional profiles as the same isolates grown on reconstituted CF patient sputum (33). However, we have recently revealed that when commercial mucins are prepared such that low-molecular-weight metabolites are removed, P. aeruginosa growth is significantly impaired. Growth was improved by an order of magnitude (>10-fold) when cocultured with mucin-degrading anaerobes (34). This observation suggested an inefficient use of intact mucin glycoproteins by the primary CF pathogen; however, despite this limitation, any growth of P. aeruginosa on mucin may have relevance to its growth in vivo. Motivated by this possibility, we further characterized here the growth of P. aeruginosa PA14 on intact PGM. In addition, we used transposon insertion sequencing (TnSeq) (35, 36) to identify the mechanisms by which P. aeruginosa degrades and consumes mucins when provided as a sole carbon source. Among essential loci were genes associated with the glyoxylate pathway and amino acid biosynthesis. Further characterization confirmed that both acetate and amino acids are consumed throughout a biphasic growth pattern. Finally, mutant analyses demonstrated the requirement of isocitrate lyase (AceA) and extracellular proteases (LasB and AprA), suggesting that the liberation of both acetate and amino acids from airway mucins has implications for P. aeruginosa growth in vivo.

RESULTS

PA14 exhibits an inefficient, biphasic growth phenotype using mucins as a growth substrate.

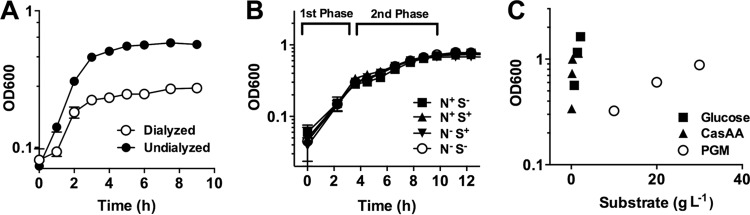

To assess the ability of PA14 to break down and metabolize intact mucins, porcine gastric mucin (PGM) was prepared by autoclaving, followed by dialysis to remove low-molecular-weight metabolites. This ensured that any observed growth was due to the use of large, intact glycoproteins. PA14 grew to a density of 0.58 in 10 g liter−1 undialyzed mucins; however, when PGM was dialyzed, the final density fell to 0.25 (Fig. 1A; 1 optical density unit [OD] is equal to ∼1.4 × 109 CFU ml−1). These data suggest that over half of the bioavailable nutrients for PA14 in the undialyzed mucin preparation were composed of small metabolites.

FIG 1.

P. aeruginosa utilizes mucins inefficiently in a biphasic growth pattern. (A) PA14 growth on dialyzed PGM (10 g liter−1) achieves half the final density relative to undialyzed preparations. (B) PA14 displays identical biphasic growth in the presence and absence of sulfur (MgSO4) and nitrogen (NH4Cl) supplements when growing with 30 g liter−1 PGM. (C) PA14 growth yields (OD g−1 liter−1) on glucose and Casamino Acids far exceeded yield obtained with dialyzed PGM. Data are shown as means ± the standard errors of the mean (SEM) from three biological replicates (n = 3).

To facilitate the study of P. aeruginosa growth on intact mucins, we then increased the purified PGM content in the culture medium to 30 g liter−1, well above physiological concentrations. Under these conditions, a biphasic growth pattern was observed (Fig. 1B, Fig. S1). Growth up to 0.35 OD (“first phase”) proceeded with a doubling time approximately twice that of growth from 0.35 to 0.8 OD (“second phase”) (Fig. 1B), which reached its peak cell density after 11 h. To determine whether there was an unfulfilled nutrient requirement that limited P. aeruginosa growth in either growth phase, we then grew PA14 on PGM with or without supplements of sulfur (magnesium sulfate, 1 mM) and nitrogen (ammonium chloride, 60 mM) (Fig. 1B). Neither supplement stimulated an increase in cell density, suggesting that the limiting nutrient of our minimal mucin medium (MMM) was likely carbon.

To assess the efficiency of PA14 to utilize PGM relative to other carbon sources (e.g., the constituent amino acids and sugars in mucin glycoproteins), we then compared growth yields of PA14 when grown on glucose, Casamino Acids [CasAA], and PGM alone (Fig. 1C). On the basis of 1 OD per g of substrate added, PA14 obtained ∼25× the density using glucose and ∼115× the density using CasAA relative to mucin (3.33 ± 0.0, 0.75 ± 0.01, and 0.029 ± 0.001 OD g−1 liter−1 for CasAA, glucose, and PGM, respectively). Given that dialyzed mucins were found to not be inhibitory to Pseudomonas growth (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), the limited growth yield of PA14 on mucin relative to other carbon sources underscores the inefficient use of these glycoproteins by P. aeruginosa.

TnSeq reveals a need for glyoxylate bypass in mucin utilization.

Despite the inefficient growth of P. aeruginosa on mucins, any breakdown and metabolism of these glycoproteins may be relevant to pathogen growth and persistence within the CF airways. Therefore, we sought to determine the mechanisms by which PA14 utilizes intact mucins in the absence of a complex, mucin-degrading bacterial community (34). To do so, we used a high-throughput transposon insertion sequencing approach, TnSeq, to identify the genetic requirements for P. aeruginosa throughout its biphasic growth phenotype described in Fig. 1B. This method allows for a comprehensive, single-culture mutant screen using a pooled transposon library and outgrowth of that library under a set of selective conditions, followed by Illumina sequencing to provide a semiquantitative measure of fitness for each gene. Using the sequencing output, a fitness score for transposon insertions at each genetic locus can be calculated. We applied this technique to study PA14 growth under selection in the first (rapid) growth phase and the second (slow) growth phase for ∼10 generations each.

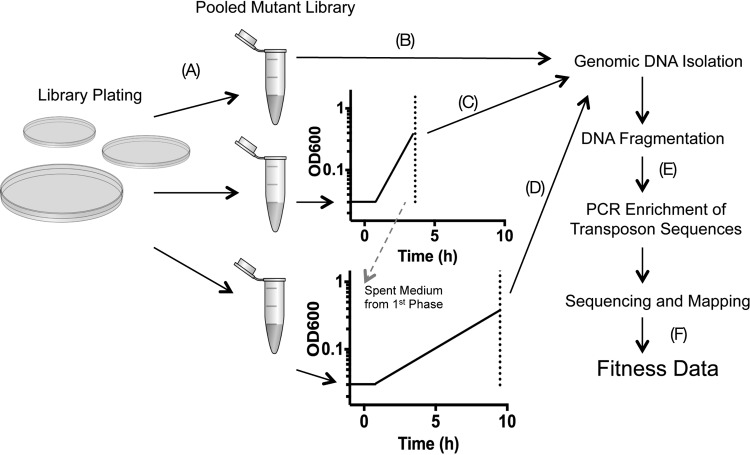

Our experimental approach is shown in Fig. 2. A library of ∼70,000 transposon mutants was isolated on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates, pooled, and frozen. To perform the selection experiments, an aliquot was thawed and used to inoculate the MMM growth medium, and the remaining culture was then pelleted and frozen for genomic DNA isolation. Two medium conditions were then tested for selection: (i) dialyzed MMM and (ii) MMM depleted of the “first-phase” carbon source. To achieve the latter, PA14 was grown in MMM until an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4, and the spent medium was filter sterilized. Media were then inoculated to 0.02 OD from the parent library and were allowed to grow to an OD600 of ∼0.4. The resulting cultures were then reinoculated to 0.02 OD and allowed to grow again to 0.4. Total growth was equal to ∼10 doublings. Genomic DNA directly adjacent to each transposon insertion was then sequenced, and insertion sites for each genetic locus in both the outgrowth and parent libraries were quantified. Using the relative abundance of transposon insertions at each locus, fitness scores were calculated for the essentiality of each gene in the two outgrowth conditions (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The parent library contained 59,380 unique transposon insertion sites with an average of 8.7 insertions in the central 85% of the coding region. To calculate fitness values for each gene under a given selection condition, the number of reads mapped to a given gene in the outgrowth library was divided by the number of reads in the parent library, followed by a log2 conversion to calculate fold changes between populations. After this transformation, a score of −2 or less was interpreted as a significant fitness defect.

FIG 2.

TnSeq experimental approach. (A) A transposon insertion library of PA14 is first constructed in which each mutant colony contains a single transposon insertion in its genome. (B to D) DNA is isolated from one aliquot of the pooled library (B), while two others are used as the source inoculum for two conditions under which selection is performed: minimal mucin medium (C) and filter-sterilized mucin medium from the first phase in which nutrients have been depleted (D). Genomic DNA is also isolated from each recovered culture. (E) Fragmented DNA is then PCR amplified generating bacterium-specific sequences flanked by Illumina-specific sequences with unique barcodes. (F) Sequence reads are then assigned to each selection condition based on their barcode identifier, mapped to the PA14 genome counted, and used to calculate a fitness score of each transposon insertion.

A total of 68 genes were found to be required for PA14 growth on mucin (see Table S3 in the supplemental material), including 30 known to be involved in metabolic processes (Table 1). Among these, multiple genes required for the first growth phase were not required for the second growth phase. In contrast, no genes associated with metabolism were identified that were required for the second growth phase but not required for the first. Of particular interest were the transposon insertions in multiple genes encoding glyoxylate pathway enzymes that had decreased fitness in the first growth phase. These included aceA, encoding isocitrate lyase, and glcB, encoding malate synthase. Fitness defects in these transposon mutants suggested that the primary carbon source during rapid growth (first phase) could be either a two-carbon compound (e.g., acetate) or fatty acids, both of which require the action of the glyoxylate pathway for growth when used as the sole carbon source. In addition to glyoxylate requirements, PA14 also required multiple genes encoding amino acid biosynthesis enzymes (arg, cys, ilv, leu, met, and trp). These requirements suggested that, although P. aeruginosa was grown on a carbon-rich glycoprotein, any liberation of amino acids from the mucin polypeptide was not rapid enough to satisfy its nutritional requirements during the first growth phase.

TABLE 1.

TnSeq fitness values for genes required for growth on mucin

| Category and gene | TnSeq fitness value |

Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First phase | Second phase | ||

| Central metabolism | |||

| aceA | −4.40 | 0.29 | Glyoxylate pathway |

| fumA | −3.20 | −0.60 | TCA cycle, fumarase |

| glcB | −4.47 | −0.59 | Glyoxylate pathway |

| Amino acid biosynthesis | |||

| argD | −2.66 | 0.02 | Arginine biosynthesis |

| cysG | −2.05 | −0.52 | Cysteine biosynthesis |

| cysH | −6.45 | 0.35 | Cysteine biosynthesis |

| hom | −6.11 | −0.46 | Amino acid biosynthesis |

| ilvC | −5.20 | −0.36 | Isoleucine biosynthesis |

| ilvD | −6.82 | −0.64 | Isoleucine biosynthesis |

| ilvI | −5.14 | −0.19 | Branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis |

| leuA | −4.93 | −0.02 | Leucine biosynthesis |

| leuB | −8.44 | 0.03 | Leucine biosynthesis |

| metW | −6.50 | −0.22 | Methionine biosynthesis |

| metX | −5.24 | −0.61 | Methionine biosynthesis |

| metZ | −6.30 | −0.15 | Methionine biosynthesis |

| orfK | −2.52 | −0.11 | Arginine biosynthesis |

| trpB | −4.05 | −0.93 | Tryptophan biosynthesis |

| trpE | −4.50 | −0.14 | Tryptophan biosynthesis |

| tyrB | −4.29 | −0.19 | Tyrosine biosynthesis |

| Nucleotide biosynthesis | |||

| carB | −7.62 | −0.70 | Pyrimidine biosynthesis |

| gda1 | −4.40 | 0.97 | Purine biosynthesis |

| purF | −4.80 | −2.18 | Purine biosynthesis |

| purL | −5.78 | 0.89 | Purine biosynthesis |

| purN | −4.32 | 0.06 | Purine biosynthesis |

| wbpM | −2.10 | −0.41 | Nucleotide sugar epimerase |

| Cofactor biosynthesis | |||

| bioA | −2.64 | −0.29 | Biotin biosynthesis |

| bioB | −2.67 | −0.80 | Biotin biosynthesis |

| gshA | −3.41 | −0.70 | Glutathione biosynthesis |

| nadB | −2.14 | 0.21 | NAD biosynthesis |

| spuC | −2.07 | −0.92 | Polyamine biosynthesis |

Among genes associated with metabolism (Table 1), the second, slower growth phase showed no defects conferred by single transposon insertions compared to the first growth phase alone. These results, in contrast to the first phase, are indicative of a diverse nutritional substrate pool whereby the disruption of a single gene does not confer a growth defect. For example, PA14 did not require any specific amino acid biosynthetic genes in the second phase, suggesting that a complete mix of amino acids were liberated from mucins and were available as “community goods.” Under these conditions, transposon insertions that would otherwise result in a growth-inhibited phenotype for an auxotrophic mutant in pure culture might not confer a defect in a community of pooled transposon mutants with mixed abilities. Given the lack of amino acid biosynthetic genes required for the second growth phase, we hypothesized that amino acids were being liberated from mucins and serving as the primary source of carbon and energy.

PA14 consumes acetate and amino acids throughout growth on mucins.

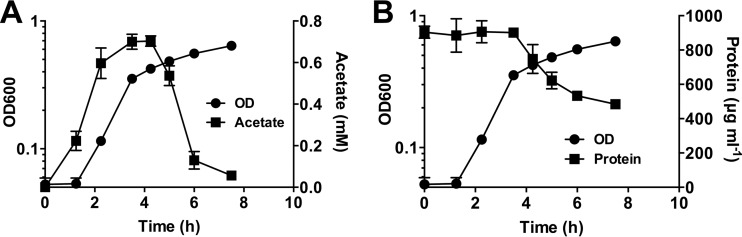

Given the requirement for the glyoxylate pathway in the first growth phase and the abundance of acetylated sugars known to decorate the mucin polypeptide (11), we hypothesized that acetate was liberated from PGM. To assess this, we monitored free acetate concentrations in the medium throughout growth. Though no acetate was initially present in the growth medium, it rapidly accumulated in the culture supernatant (Fig. 3A). Its concentration increased until the transition between the first and second growth phases (∼0.3 OD), where it was rapidly consumed. This result is consistent with the glyoxylate pathway being required for the first growth phase in which two-carbon compounds serve as a primary carbon source.

FIG 3.

Acetate and protein content during mucin growth. (A) Acetate accumulates in the growth medium followed by its rapid consumption by P. aeruginosa. (B) Total protein also decreases in the second growth phase, suggesting amino acid liberation from the mucin polypeptide. Data are shown as mean concentrations ± the SEM from three biological replicates (n = 3).

Given that no amino acid biosynthetic genes were essential in the second growth phase, we predicted that amino acids were liberated via degradation of the mucin glycoprotein. We therefore quantified total protein content (excluding free amino acids) in the medium supernatant (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, protein concentration remained unchanged in the first phase of growth, and rapidly declined in the second phase, reflecting a degradation of the mucin polypeptide. Taken together, these observations demonstrate a sequential use of carbon sources (acetate, followed by amino acids) corresponding to the biphasic growth phenotype.

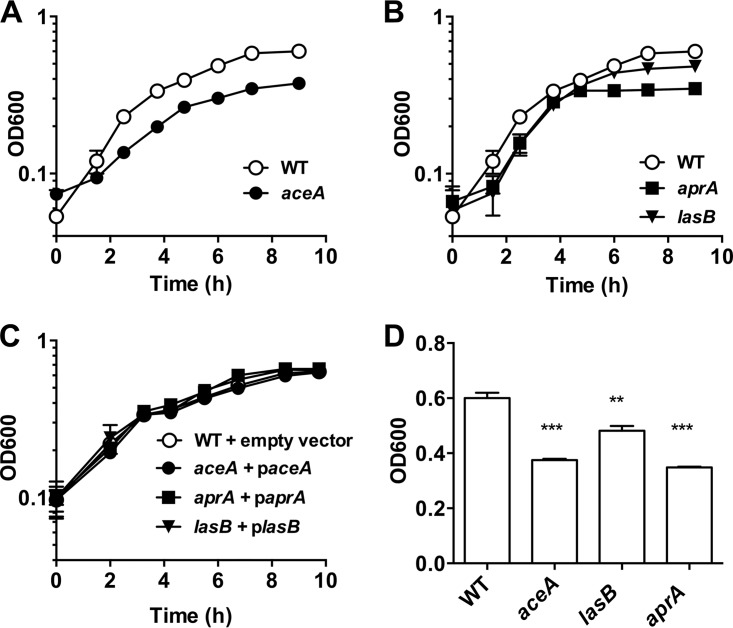

The growth of aceA, lasB, and aprA mutants demonstrates growth defects in PGM.

To confirm the importance of acetate and the glyoxylate pathway in the first phase of growth, a clean deletion was made in aceA, encoding isocitrate lyase, which catalyzes the first step in the glyoxylate pathway. Any strain lacking this committed step would not be able to use acetate as a sole carbon source because it would be unable to correctly balance carbon requirements in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. Consistent with this limitation, the ΔaceA mutant demonstrated a marked growth defect relative to WT and reached a lower final density (Fig. 4A and D). Complementation showed restoration of the WT phenotype (Fig. 4C). The impaired growth of the ΔaceA mutant on mucin was not observed on glucose, ruling out a general growth defect (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The incomplete abolishment of growth suggests that the ΔaceA mutant is concurrently obtaining carbon via other means but that the glyoxylate pathway defect restricts its growth and overall yield.

FIG 4.

AceA, LasB, and AprA are utilized for PA14 mucin growth. (A) Deletion of aceA, encoding isocitrate lyase, confers a partial growth defect in P. aeruginosa when provided mucins as the sole carbon source. (B) The extracellular proteases LasB and AprA are also required for the degradation and consumption of mucin polypeptides. (C) Complementation of ΔaceA, ΔlasB, and ΔaprA restores the wild-type phenotype. (D) Comparison of final growth yields (OD600) reveals significant growth defects in aceA, lasB, and aprA mutants. Data are shown as means ± the SEM from three biological replicates (n = 3). Statistical significance of each mutant relative to the wild type was determined by using an unpaired Student t test (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Protein consumption in the second growth phase suggested that one or more extracellular proteases were being used to degrade the mucin polypeptide backbone. To address this possibility, we identified and tested four extracellular proteases (LasA, LasB, AprA, and SppA) that may be important for the degradation of extracellular peptides. Deletions were made in genes encoding each of these proteases, and their growth was assayed versus the WT in MMM. Interestingly, only mutants lacking LasB and AprA exhibited defects in the second phase of growth (Fig. 4B; see also Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) and lower final densities (Fig. 4D), whereas complementation with lasB or aprA, respectively, restored the WT phenotype (Fig. 4C). These data demonstrate that elastase (LasB) and alkaline protease (AprA) are used by P. aeruginosa during the second growth phase and reveal a genetic basis for the sequential use of the mucin-derived carbon sources described above.

DISCUSSION

In contrast to Streptococcus, Akkermansia, Bacteroides, and other bacterial genera that have an extensive repertoire of enzymes devoted to catabolizing host-associated glycoproteins in the gut and oral cavity (24, 37–40), the primary CF pathogen, P. aeruginosa, is not known to encode any glycosidases used in the breakdown of respiratory mucins. Indeed, we demonstrate here that strain PA14 uses intact mucins inefficiently compared to its carbohydrate and amino acid monomeric constituents (glucose and Casamino Acids). However, when purified and dialyzed mucins were provided at high concentrations, we observed a slow, biphasic growth of PA14 to an appreciable density. This observation suggests that even a partial breakdown of mucin glycoproteins may support the slow growth and persistence of P. aeruginosa in the CF airways.

The limited degradation of swine-derived mucins by strain PA14 was not unexpected; in the oral cavity, for example, diverse consortia of bacteria are required to completely break down salivary mucins (40). However, our data are in contrast to previous studies that have implicated P. aeruginosa and another CF pathogen, Burkholderia cenocepacia, in the degradation of mucins within the airways (25, 29). We propose that this discrepancy may be explained by the limitations of mucin detection methods. Immunoblotting, a commonly used approach for evaluating mucin content, relies on anti-MUC5AC and anti-MUC5B antibodies directed toward their epitopes on the terminal, nonglycosylated regions (i.e., apomucin) of the macromolecule, as previously shown (41). Given that extracellular proteases (and not glycosidases) were found here to be essential for PA14 growth on PGM, we suspect that proteolytic degradation removes only the terminal polypeptide regions, leaving the bulk of the mucin glycoprotein intact. This limited degradation would give the impression of more extensive mucin breakdown via Western immunoblotting (41). Consequently, we favor the interpretation that mucinase activity previously ascribed to P. aeruginosa is likely due to terminal polypeptide degradation mediated by the extracellular proteases (LasB and AprA) described here.

TnSeq analysis implied a critical role for the glyoxylate shunt (aceA and glcB) in the generation and consumption of nutrients during the first phase of mucin growth. The essentiality of this pathway implies a requirement for C2 carbon metabolism and led to the discovery of the use of acetate by P. aeruginosa during growth on PGM. The requirement for the glyoxylate pathway stems from the fact that carbon sources entering central metabolism below pyruvate must go through the TCA cycle to malate to be fed to gluconeogenic pathways. To correctly balance TCA cycle metabolites, the glyoxylate pathway is needed for the regeneration of four carbon intermediates (e.g., malate) that have been removed for anabolic pathways. Although the glyoxylate shunt is also essential for fatty acid and lipid metabolism under nutrient-limited growth conditions, direct measurements of the culture supernatant confirmed that acetate accumulates in the growth medium, followed by its consumption. We hypothesize that acetate is likely derived via deacetylation of sugars (N-acetylglucosamine, N-acetylgalactosamine, and sialic acids) that decorate the polypeptide backbone. Further studies are required to determine the source and enzymes responsible for the accumulation of this metabolite.

Interestingly, the glyoxylate pathway has been implicated in various in vivo infection models. For example, an isocitrate lyase mutant (ΔaceA) of P. aeruginosa demonstrated significantly less virulence and host tissue damage in a rat lung infection model (42). In addition, a ΔaceA ΔglcB double mutant of P. aeruginosa was cleared by 48 h postinfection in a murine acute pneumonia model (43) and yet showed no defective phenotypes in septicemia, underscoring its importance in the mucin-rich environment of the lower airways. Son et al. (44) demonstrated that genes required for the glyoxylate cycle in P. aeruginosa are highly expressed within sputum derived from CF patients, while others have reported that aceA is more highly expressed in CF P. aeruginosa isolates compared to those derived from non-CF sources when isolates are grown in vitro (45). Notably, acetate has also been found at elevated concentrations within CF sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (34, 46, 47). Our data, when considered in the context of the aforementioned studies, support a role for the glyoxylate shunt in respiratory mucin degradation by P. aeruginosa. Moreover, since isocitrate lyase (AceA) and malate synthase (GlcB) have no known ortholog in humans, our data also provide further motivation to explore the glyoxylate shunt as a target for antipseudomonal therapy, as previously suggested (48–51).

Although TnSeq did not identify extracellular proteases, mutant analysis demonstrated that lasB and aprA, encoding elastase B and alkaline protease, respectively, were also key enzyme genes required for mucin-based growth. Elastase B is a quorum sensing-regulated, prototypical virulence factor of P. aeruginosa (52, 53) and has been shown to degrade a wide variety of host proteins such as collagen, elastin, immunoglobulins, and complement (54). Similarly, AprA (aeruginolysin) is a metalloendopeptidase that has also been shown to degrade physiological substrates in vivo (54). Although it is possible that other, yet-to-be-identified proteases also contribute to mucin degradation, both LasB and AprA have been detected in abundance in the CF airways (55–58). Importantly, both lasB and aprA mutants have also shown attenuated virulence in animal infection models (59, 60), suggesting an important role for these proteases in airway pathogenesis. Given that both enzymes have also been implicated in bacterial keratitis, where colonization of the corneal layer was restricted in both LasB- and AprA-deficient mutants (61, 62), we speculate that these two proteases are also important for P. aeruginosa nutrient acquisition and persistence at other mucin-rich sites of infection.

Understanding how respiratory pathogens adapt to the in vivo nutritional environment has important implications for the treatment of CF lung disease. As a step in this direction, this genome-wide survey of mucin utilization strategies has provided a window into a potential mechanism of P. aeruginosa growth within the lower airways. Although growth on mucins was limited, our data demonstrate that mucin degradation alone can support low densities of PA14, which may allow for bacterial persistence when nutrients are scarce (e.g., early stages of disease). We concede that the portrait of in vivo pathogen growth is never simple in a disease with an array of etiologies. It is likely that as airway infections evolve, the bacterial community and the host airway milieu change over time and between patients such that bioavailable nutrient pools are altered. Going forward, it will be important to consider how bacterial carbon acquisition strategies vary with disease states and how they can be manipulated as a means of mitigating chronic CF airway infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

A list of bacterial strains and plasmids is provided in Table 2. All strains were routinely cultured in LB broth (Difco) and LB agar. Gentamicin sulfate (50 μg ml−1) and 2,6-diaminopimelic acid (DAP; 250 μM) were added where necessary. Mucin minimal medium (MMM) was prepared as described previously (34). Briefly, porcine gastric mucins (type III; Sigma-Aldrich) were dissolved in water to 30 g liter−1 and autoclaved. Mucins were then dialyzed against ultrapure water with a 13-kDa molecular-size-cutoff dialysis membrane and clarified by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 30 min. MMM was made by adding the specified amount of mucins to a defined medium containing 60 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7.4), 90 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgSO4, and a trace mineral mix described elsewhere (63). The final MMM was also filter sterilized (0.45-μm pore size). For growth with glucose or Casamino Acids (CasAA), the MMM described above was used without mucin but with added glucose or CasAA at the specified concentrations. Minimal glucose cultures were also supplemented with 60 mM NH4Cl.

TABLE 2.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| PA14 | Clinical isolate UCBPP-PA14 | 64 |

| PA14ΔlasA | PA14 with a deletion of PA14_40290 (lasA) | This study |

| PA14ΔlasB | PA14 with a deletion of PA14_16250 (lasB) | This study |

| PA14ΔsppA | PA14 with a deletion of PA14_25600 (sppA) | This study |

| PA14ΔaprA | PA14 with a deletion of PA14_48060 (aprA) | This study |

| PA14ΔaceA | PA14 with a deletion of PA14_30050 (aceA) | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| UQ950 | DH5α λpir | 69 |

| WM3064 | Donor strain for conjugations | 69 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEB001 | pMiniHimar RB-1 with MmeI sites | 65 |

| pJF1 | pEB001 with Gentr | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-5 | Broad host range vector; Gentr | 67 |

| pBBR1MCS-5 lasB | Complementation vector for lasB | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-5 aprA | Complementation vector for aprA | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-5 aceA | Complementation vector for aceA | This study |

| pSMV8lasA | Deletion vector for lasA | This study |

| pSMV8lasB | Deletion vector for lasB | This study |

| pSMV8sppA | Deletion vector for sppA | This study |

| pSMV8aprA | Deletion vector for aprA | This study |

| pSMV8aceA | Deletion vector for aceA | This study |

Growth on mucins.

For growth assays, a colony was picked from freshly streaked LB agar, inoculated into LB broth, and allowed to grow for 16 h. Cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline before inoculation into 5 ml of MMM to an initial OD600 of ∼0.05. Tubes were aerated by shaking continuously at 200 rpm at 37°C, and the OD600 was monitored over time using a Spectronic 20 spectrophotometer (Bausch and Lomb). Aliquots (100 μl) were removed throughout growth where specified, immediately frozen at −80°C, and stored for downstream analysis. Experiments were performed using biological triplicates (n = 3), and unpaired Student t tests were used to identify significant differences in the optical density.

Protein and acetate quantification.

Previously frozen samples were centrifuged, and 30 μl of the supernatant was used for acetate quantification using a colorimetric assay kit (Biovision) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Then, 10 μl of the same sample was assayed for protein content using the Qubit fluorometry system (Thermo-Fisher).

TnSeq.

TnSeq protocols were based on previously published methods (36, 65). First, the previously modified mariner transposon (66) was further modified to replace the kanamycin resistance cassette with a gentamicin cassette for use in P. aeruginosa. Briefly, the plasmid containing the transposon and transposase (pEB001) (65) was used as the template in a PCR using TnSwap1 and TnSwap2 (a list of primers is shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material) to generate a fragment containing the whole pEB001 plasmid lacking a selectable marker. Next, the gene encoding gentamicin acetyltransferase (Gentr) was amplified from pBBR1MCS-5 (67) using GentR_Fwd and GentR_Rev primers. Gibson assembly (68) was used to combine Gentr with the linearized pEB001 plasmid generated by PCR described above to create pJF1. Next, pJF1 was transformed into the conjugative mating strain WM3064 (69), and a saturating transposon mutant library was generated by mating P. aeruginosa PA14 with WM3064 (containing pJF1) on LB plus DAP agar plates, followed by selection on LB gentamicin (50 μg ml−1). Mutants (∼70,000) were pooled en masse in LB medium plus 15% glycerol and frozen in 100-μl aliquots.

Outgrowth experiments are described in Fig. 2. Briefly, one 100-μl aliquot was pelleted and frozen for genomic DNA (gDNA) extraction (“Parent”). A second glycerol stock was thawed and then washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline before inoculation into 5 ml of MMM to an OD600 of 0.02. Cultures were shaken at 250 rpm at 37°C, and the OD600 was monitored until the cells reached ∼0.4. Next, 0.25 ml of this culture was used to inoculate a fresh 5 ml of MMM, and the sample was allowed to grow to ∼0.4 OD (representing approximately 10 doublings [“first phase”]). A second culture was prepared by inoculating an additional 100-μl glycerol stock into filter-sterilized spent growth medium from the first phase, followed by outgrowth to ∼0.4 OD. As described above, 0.25 ml was used to inoculate a fresh 5 ml of spent medium and cells were allowed to grow again to ∼0.4 (∼10 doublings, “second phase”). Bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation and frozen at −80°C.

Genomic DNA was extracted from frozen cell pellets using a Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega), cut with MmeI restriction enzyme (New England BioLabs), and treated with calf intestinal phosphatase (New England BioLabs). Oligonucleotide adapters (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) with a 3′-NN overhang containing appropriate sequences for Illumina sequencing were ligated to the resulting fragments using T4 ligase (New England BioLabs). Adapters were barcoded with a unique 4-bp sequence to enable multiplexing. PCR was then performed using ligation reactions as the template with primers specific for the inverted repeat region on the transposon and the ligated adapter (P1_M6_MmeI and Gex_PCR_Primer, respectively). These primers introduce sequences suitable for direct sequencing in an Illumina flow cell. The resulting reaction product (120 bp) was purified by gel extraction using a PureLink Quick gel extraction kit (Life Technologies) and sent to the University of Minnesota Biomedical Genomics Center for sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform (single end, 50 bp). Downstream analysis was performed on the Galaxy server (70–72) at the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute. Reads were split by unique barcode and trimmed to obtain the sequence adjacent to the transposon insertion. The resulting sequence was mapped to the PA14 genome (GenBank accession number GCA_000014625.1) using Bowtie, discarding reads with a >1-bp mismatch and sequences mapping to multiple locations. Insertions within the first 5% and last 10% of the open reading frame were also discarded to provide greater assurance that the insertion resulted in a null mutation. With these parameters, the parent, first phase, and second phase had 27 million, 17 million, and 10 million total mapped hits, respectively. Genes with fewer than 10 unique insertions (e.g., sucD) in the parent library were removed from analysis to limit their associated variability. Fitness values for each gene were then scored by computing a hit-normalized fold change for each growth condition [log2(outgrowth library hits/parent library hits)]. This calculation identifies the fold change in transposon mutant abundance between the parent and outgrowth populations (i.e., for a gene with a score of −2, there were 4 times the number of cells containing a mutation in the parent library compared to the outgrowth). Negative fold changes signified mutations with fitness defects under the outgrowth condition and were specific to the phase in which they were grown (i.e., not additive between the first and second phases).

Genetic manipulation.

In-frame, markerless deletions in PA14 were generated using established homologous recombination techniques. Plasmids (Table 2) were derived from the suicide vector pSMV8 (69) and manipulated using standard molecular biology protocols with Escherichia coli DH5α (UQ950). For deletion constructs, 1,000-bp regions flanking the gene to be deleted (including three to six codons of the beginning and end of the genes) were amplified by PCR using primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Fragments were joined and cloned into pSMV8 digested with SpeI and XhoI using Gibson assembly and chemically transformed into UQ950. Positive ligations were screened by PCR, transformed into E. coli strain WM3064, and mobilized into PA14 by conjugation. Recombinants of PA14 were selected for on LB agar plates containing gentamicin, and double recombinants were selected for on LB agar containing 6% sucrose. Complementation vectors were constructed by cloning the gene (lasB, aprA, or aceA) with an additional ∼50 bp upstream of the start site, followed by ligation into pBBR1MCS-5. Briefly, fragments were amplified by PCR using gene-specific primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Resulting fragments were gel purified and digested using the restriction enzymes KpnI, SacI, and XhoI where appropriate. After digestion, purified fragments were combined with digested pBBR1MCS-5, ligated using T4 ligase, and transformed into UQ950. Positive transformants were screened by PCR and confirmed by sequencing. Complementation constructs were mated into PA14 via conjugation using WM3064 as described above. Successful matings were selected for by plating on LB agar containing gentamicin. All constructs and deletions were verified by sequencing.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Caleb Levar and Chi-Ho Chan (BioTechnology Institute, University of Minnesota) for their assistance with TnSeq, and we acknowledge the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute.

This study was supported by a Pathway to Independence Award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) to R.C.H. (R00HL114862) and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000114). J.M.F. was supported by a National Institutes of Health Lung Sciences T32 fellowship (2T32HL007741-21) awarded through the NHLBI and by a Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship (FLYNN16F0).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00182-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kerem BR, Rommens JM, Buchanan JA, Markiewicz D, Cox TK, Chakravarti A, Buchwald M, Tsui LC. 1989. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: genetic analysis. Science 245:1073–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.2570460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis PB. 2006. Cystic fibrosis since 1938. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 173:475–482. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200505-840OE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubin BK. 2007. Mucin structure and properties in cystic fibrosis. Paediatr Respir Rev 8:4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyczak JB, Cannon CL, Pier GB. 2000. Establishment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection: lessons from a versatile opportunist. Microb Infect 2:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)01259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoiby N, Johansen HK, Moser C, Song Z, Ciofu O, Kharazmi A. 2001. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the in vitro and in vivo biofilm mode of growth. Microb Infect 3:23–35. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)01349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer KL, Mashburn LM, Singh PK, Whiteley M. 2005. Cystic fibrosis sputum supports growth and cues key aspects of Pseudomonas aeruginosa physiology. J Bacteriol 187:5267–5277. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5267-5277.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voynow JA, Rubin BK. 2009. Mucins, mucus and sputum. Chest 135:505–512. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamblin G, Degroote S, Perini JM, Delmotte P, Scharfman A, Davril M. 2001. Human airway mucin glycosylation: a combinatory of carbohydrate determinants which vary in cystic fibrosis. Glycoconj J 18:661–684. doi: 10.1023/A:1020867221861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kreda SM, Davis CW, Rose MC. 2012. CFTR, mucins, and mucus obstruction in cystic fibrosis. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Med 2:a009589. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rose MC. 1988. Epithelial mucous glycoproteins and cystic fibrosis. Hormone Metab Res 20:601–608. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rose MC, Voynow JA. 2006. Respiratory tract mucin genes and mucin glycoproteins in health and disease. Physiol Rev 86:245–278. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thornton DJ, Rousseau K, McGuckin MA. 2007. Structure and function of the polymeric mucins in airway mucus. Annu Rev Physiol 70:459–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arora SK, Ritchings BW, Almira EC, Lory S, Ramphal R. 1998. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa flagellar cap protein, FliD, is responsible for mucin adhesion. Infect Immun 66:1000–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carnoy C, Ramphal R, Scharfman A, Lo-Guidice JM, Houdret N, Klein A, Galabert C, Lamblin G, Roussei P. 1993. Altered carbohydrate composition of salivary mucins from patients with cystic fibrosis and the adhesion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 9:323. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/9.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramphal R, Arora SK. 2001. Recognition of mucin components by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Glycoconj J 18:709–713. doi: 10.1023/A:1020823406840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caldara M, Friedlander RS, Kavanaugh NL, Aizenberg J, Foster KR, Ribbeck K. 2012. Mucin biopolymers prevent bacterial aggregation by retaining cells in the free-swimming state. Curr Biol 22:2325–2330. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haley CL, Kruczek C, Qaisar U, Colmer-Hamood JA, Hamood A. 2014. Mucin inhibits Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation by significantly enhancing twitching motility. Can J Microbiol 60:155–166. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2013-0570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landry RM, An D, Hupp JT, Singh PK, Parsek MR. 2006. Mucin-Pseudomonas interactions promote biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance. Mol Microbiol 59:142–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Staudinger BJ, Muller MF, Halldorsson S, Boes B, Angermeyer A, Nguyen D, Rosen H, Baldursson O, Gottfeosson M, Gudmundsson GH, Singh PK. 2014. Conditions associated with the cystic fibrosis defect promote chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Am J Crit Care Med 189:812–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201312-2142OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeung ATY, Parayno A, Hancock REW. 2012. Mucin promotes rapid surface motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mBio 3:e00073-12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00073-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lory S, Jin S, Boyd JM, Rakeman JL, Bergman P. 1996. Differential gene expression by Pseudomonas aeruginosa during interaction with respiratory mucus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 154:S183. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/154.4_Pt_2.S183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berry M, Harris A, Lumb R, Powell K. 2002. Commensal ocular bacteria degrade mucins. Br J Ophthalmol 86:1412–1416. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.12.1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rho J, Wright DP, Christie DL, Clinch K, Furneaux RH, Roberton AM. 2005. A novel mechanism for desulfation of mucin: identification and cloning of a mucin-desulfating glycosidase (sulfoglycosidase) from Prevotella strain RS2. J Bacteriol 187:1543–1551. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1543-1551.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desai MS, Seekatz A, Koropatkin NM, Kamada N, Hickey CA, Wolter M, Pudlo NA, Kitamoto S, Terrapon N, Muller A, Young VB, Henrissat B, Wilmes P, Stappenback TS, Nunez G, Martens EC. 2016. A dietary fiber-deprived gut microbiota degrades the colonic mucus barrier and enhances pathogen susceptibility. Cell 167:1339–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Houdret N, Ramphal R, Scharfman A, Perini JM, Fillat M, Lamblin G, Roussei P. 1998. Evidence for the in vivo degradation of human respiratory mucins during Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Biochim Biophys Acta 992:96–105. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(89)90055-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jansen H, Hart CA, Rhodes JM, Saunders JR, Smalley JW. 1999. A novel mucin-sulfatase activity found in Burkholderia cepacia and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Med Microbiol 48:551–557. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-6-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leprat R, Michel-Briand Y. 1980. Extracellular neuraminidase production by a strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from cystic fibrosis. Ann Microbiol 131:209–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson CV, Elkins MR, Bialkowski KM, Thornton DJ, Kertesz MA. 2012. Desulfurization of mucin by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: influence of sulfate in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients. J Med Microbiol 61:1644–1653. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.047167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwab U, Abdullah LH, Perlmutt OS, Albert D, Davis CW, Arnold RR, Yankaskas JR, Gilligan P, Neubauer H, Randell SH, Boucher RC. 2014. Localization of Burkholderia cepacia complex bacteria in cystic fibrosis lungs and interactions with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in hypoxic mucus. Infect Immun 82:4729–4745. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01876-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boat TF, Chen PW, Iyer RN, Carlson DM, Polony I. 1976. Human respiratory tract secretions. Arch Biochem Biophys 177:95–104. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(76)90419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scawen M, Allen A. 1977. The action of proteolytic enzymes on the glycoprotein from pig gastric mucus. Biochem J 163:363–368. doi: 10.1042/bj1630363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sriramulu DD, Lunsdorf H, Lam JS, Romling U. 2005. Microcolony formation: a novel biofilm model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa for the cystic fibrosis lung. J Med Microbiol 54:667–676. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45969-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fung C, Naughton S, Turnbull L, Tingpej P, Rose B, Arthur J, Hu H, Harmer C, Harbour C, Hassett DJ, Whitchurch CB. 2010. Gene expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a mucin-containing synthetic growth medium mimicking cystic fibrosis lung sputum. J Med Microbiol 59:1089–1100. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.019984-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flynn JM, Niccum D, Dunitz J, Hunter RC. 2016. Evidence and role for bacterial mucin degradation in cystic fibrosis airway disease. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005846. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Opijnen T, Camilli A. 2010. Genome-wide fitness and genetic interactions by Tn-Seq, a high-throughput massively parallel sequencing method for microorganisms. Curr Protocol Microbiol 14:7–16. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc01e03s36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Opijnen T, Camilli A. 2013. Transposon insertion sequencing: a new tool for systems-level analysis of microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol 11:435–442. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Derrien M, Collado MC, Ben-Amor K, Salminen S, de Vos WM. 2008. The mucin degrader Akkermansia muciniphila is an abundant resident of the human intestinal tract. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:1646–1648. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01226-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martens EC, Chiang HC, Gordon JL. 2008. Mucosal glycan foraging enhances fitness and transmission of a saccharolytic human gut bacterial symbiont. Cell Host Microbe 4:447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terra VS, Homer KA, Rao SG, Andrew PW, Yesilkava H. 2010. Characterization of novel β-galactosidase activity that contributes to glycoprotein degradation and virulence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun 78:348–357. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00721-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bradshaw DJ, Homer KA, Marsh PD, Beighton D. 1994. Metabolic cooperation in oral microbial communities during growth on mucin. Microbiology 140:3407–3412. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-12-3407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henderson AG, Ehre C, Button B, Abdullah LH, Cai LH, Leigh MW, DeMaria GC, Matsui H, Donaldson SH, Davis CW, Sheehan JK, Boucher RC, Kesimer M. 2014. Cystic fibrosis airway secretions exhibit mucin hyperconcentration and increased osmotic pressure. J Clin Invest 124:3047–3060. doi: 10.1172/JCI73469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindsey TL, Hagins JM, Sokol PA, Silo-Suh LA. 2008. Virulence determinants from a cystic fibrosis isolate of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isocitrate lyase. Microbiology 154:1616–1627. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/014506-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fanhoe KC, Flanagan ME, Gibson G, Shanmugasundaram V, Che Y, Tomaras AP. 2012. Nontraditional antibacterial screening approaches for the identification of novel inhibitors of the glyoxylate shunt in Gram-negative pathogens. PLoS One 7:e51732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Son MS, Matthews WJ, Kang Y, Nguyen DT, Hoang TT. 2007. In vivo evidence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa nutrient acquisition and pathogenesis in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients. Infect Immun 75:5313–5324. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01807-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoboth C, Hoffmann R, Eichner A, Henke C, Schmoldt S, Imhof A, Heesemann J, Hogardt M. 2009. Dynamics of adaptive microevolution of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa during chronic pulmonary infection in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Infect Dis 200:118–130. doi: 10.1086/599360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mirkovic B, Murray MA, Lavelle GM, Molloy K, Azim AA, Gunaratnam C, Healy F, Slattery D, McNally P, Hatch J, Wolfgang M, Tunney MM, Muhlebach M, Devery R, Greene CM, McElvaney NG. 2015. The role of short-chain fatty acids, produced by anaerobic bacteria, in the cystic fibrosis airway. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 192:1314–1324. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0943OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghorbani P, Santhakumar P, Hu Q, Djiadeu P, Wolever TMS, Palaniyar N, Grasemann H. 2015. Short-chain fatty acids affect cystic fibrosis airway inflammation and bacterial growth. Eur Respir J 46:1033–1045. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00143614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anstrom DM, Remington SJ. 2006. The product complex of Mycobacterium tuberculosis malate synthase revisited. Protein Sci 15:2002–2007. doi: 10.1110/ps.062300206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dunn MF, Ramirez-Trujillo JA, Hernandez-Lucas I. 2009. Major roles of isocitrate lyase and malate synthase in bacterial and fungal pathogenesis. Microbiology 155:3166–3175. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.030858-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McKinney JD, Höner zu Bentrup K, Munoz-Elias EJ, Miczak A, Chen B, Chan WT, Swenson D, Sacchettini D, Jacobs WR, Russell DG. 2000. Persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages and mice requires the glyoxylate shunt enzyme isocitrate lyase. Nature 406:735–738. doi: 10.1038/35021074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Schaik EJ, Marina T, Woods DE. 2009. Burkholderia pseudomallei isocitrate lyase is a persistence factor in pulmonary melioidosis: implications for the development of isocitrate lyase inhibitors and novel antimicrobials. Infect Immun 77:4275–4283. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00609-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams P, Camara M. 2009. Quorum sensing and environmental adaptation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a tale of regulatory networks and multifunctional signal molecules. Curr Opin Microbiol 12:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Voynow JA, Fischer BM, Zheng S. 2008. Proteases and cystic fibrosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 40:1238–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matsumoto K. 2004. Role of bacterial proteases in pseudomonal and serratial keratitis. Biol Chem 385:1007–1016. doi: 10.1515/BC.2004.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jaffar-Bandjee MC, Lazdunski A, Bally M, Carrere J, Chazalette JP, Galabert C. 1995. Production of elastase, exotoxin A, and alkaline protease in sputa during pulmonary exacerbation of cystic fibrosis in patients chronically infected by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Clin Microbiol 33:924–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Doring G, Obernesser HJ, Botzenhart K, Flehmig B, Hoiby N, Hofmann A. 1983. Proteases of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Infect Dis 147:744–750. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.4.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suter S, Schaad UB, Roux L, Nydegger UE, Waldvogel FA. 1984. Granulocyte neutral proteases and Pseudomonas elastase as possible causes of airway damage in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Infect Dis 149:523–531. doi: 10.1093/infdis/149.4.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Upritchard HG, Cordwell SJ, Lamont IL. 2008. Immunoproteomics to examine cystic fibrosis host interactions with extracellular Pseudomonas aeruginosa proteins. Infect Immun 76:4624–4632. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01707-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liehl P, Blight M, Vodovar N, Boccard F, Lemaitre B. 2006. Prevalence of local immune response against oral infection in a Drosophila/Pseudomonas infection model. PLoS Pathog 2:e56. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Woods DE, Cryz SJ, Friedman RL, Iglewski BH. 1982. Contribution of toxin A and elastase to virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in chronic infection of rats. Infect Immun 36:1223–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Howe TR, Iglewski BH. 1984. Isolation and characterization of alkaline protease-deficient mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro and in a mouse eye model. Infect Immun 43:1058–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ohman DE, Burns RP, Iglewski BH. 1980. Corneal infections in mice with toxin A and elastase mutant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Infect Dis 142:836–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marsili E, Rollefson JB, Baron DB, Hozalski RM, Bond DR. 2008. Microbial biofilm voltammetry: direct electrochemical characterization of catalytic electrode-attached biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:7329–7337. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00177-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rahme LG, Stevens EJ, Wolfort SF, Shao J. 1995. Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals. Science 268:1899. doi: 10.1126/science.7604262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brutinel ED, Gralnick JA. 2012. Anomalies of the anaerobic tricarboxylic acid cycle in Shewanella oneidensis revealed by Tn-Seq. Mol Microbiol 86:273–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hartl DL. 1989. Transposable element mariner in Drosophila species, p 5531–5536. In Berg DE, Howe MM (ed), Mobile DNA. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop RM, Peterson KM. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, Smith HO. 2009. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods 6:343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saltikov CW, Newman DK. 2003. Genetic identification of a respiratory arsenate reductase. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A 100:10983–10988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834303100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Giardine B, Riemer C, Hardison RC, Burhans R, Elnitski L, Shah P. 2005. Galaxy: a platform for interactive large-scale genome analysis. Genome Res 15:1451–1455. doi: 10.1101/gr.4086505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blankenberg D, Von Kuster GV, Coraor N, Ananda G, Lazarus R, Mangan M, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J. 2010. Galaxy: a web-based genome analysis tool for experimentalists. Curr Protoc Mol Biol 2010:Chapter 19:Unit 19.10.1-21. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1910s89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Goecks J, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J. 2010. Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol 11:1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.