Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To assess the immunogenicity of thermostable live-attenuated rabies virus (RABV) preserved by vaporization (PBV) and delivered to the duodenal mucosa of a wildlife species targeted by an oral vaccination program.

ANIMALS

8 gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus).

PROCEDURES

Endoscopy was used to place RABV PBV, alginate-encapsulated RABV PBV, or nonpreserved RABV into the duodenum of each fox. Blood samples were collected weekly to monitor the immune response. Saliva samples were collected weekly and tested for virus shedding by use of a conventional reverse-transcriptase PCR assay. Foxes were euthanized 28 days after vaccine administration, and relevant tissues were collected and tested for presence of RABV.

RESULTS

2 of 3 foxes that received RABV PBV and 1 of 2 foxes that received nonpreserved RABV seroconverted by day 28. None of the 3 foxes receiving alginate-encapsulated RABV PBV seroconverted. No RABV RNA was detected in saliva at any of the time points, and RABV antigen or RNA was not detected in any of the tissues obtained on day 28. None of the foxes displayed any clinical signs of rabies.

CONCLUSIONS AND CLINICAL RELEVANCE

Results for this study indicated that a live-attenuated RABV vaccine delivered to the duodenal mucosa can induce an immune response in gray foxes. A safe, potent, thermostable RABV vaccine that could be delivered orally to wildlife or domestic animals would enhance current rabies control and prevention efforts.

Most of the rabies cases in humans occur in developing countries where canine rabies is enzootic and access to rabies biologics is limited.1,2 The cost associated with canine rabies is estimated at $124 billion annually3, and it is estimated that there are 26,000 to 86,000 cases of rabies in humans annually as a result of exposure to canine rabies.4,5 It is believed that almost all of these cases could be prevented by elimination of canine rabies and proper administration of postexposure prophylaxis.6,7 Poor veterinary health infrastructure in countries with enzootic canine rabies has led to proposals to vaccinate children against rabies prior to exposure.8

In countries in which canine rabies has been eliminated, wildlife serve as a dominant reservoir. Oral vaccination against rabies is a proven strategy to prevent rabies in wildlife and thus spillover to domestic animals or humans.9–11 Rabies vaccines for oral administration must be stored cold (5° ± 3°C) before distribution to the environment.12–16 Stability of current vaccines differs, with some vaccines stable up to 12 months at 45°C15 and others stable up to 3 months at 37°C17; however, no manufacture recommends vaccine be stored at ambient temperature because of the risk for loss of potency.

The foam drying technique PBV effectively stabilizes RABV at ambient temperatures (30° ± 7°C) for at least 15 months.18 The RABV PBV vaccine can induce RABV-neutralizing antibodies when delivered IM and protects mice from challenge exposure.18 One advantage of PBV is the ability to micronize biologics, which allows for needle-free and traditional pharmaceutical delivery (eg, intradermal microneedle patches, intranasal inhaler, dissolvable oral gels, or gastric capsules).19,20 Investigators who attempted intestinal delivery of rabies vaccine found a limited response for multiple doses of an inactivated vaccine administered by this route to red foxes (Vulpes vulpes)21 and raccoons (Procyon lotor).22

In the study reported here, endoscopy was used to place live-attenuated nonencapsulated RABV PBV vaccine, alginate-encapsulated RABV PBV vaccine, or non-PBV RABV vaccine into the duodenum of gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus). Endoscopy was used to ensure delivery of vaccines to the intestinal mucosa. The study was required as a proof-of-concept for development of future vaccines designed for intestinal delivery. Alginate encapsulation was used for vaccine formulation on the basis of results of a study23 that indicated increased protection and persistence of the antigen. Gray foxes were selected for use because these mesocarnivores are the most abundant and widely distributed species of fox in the southeastern United States and are a target for oral vaccination campaigns in Texas.24–26

Materials and Methods

Animals

Gray foxes were purchased from a vendor.a Blood samples were collected by veterinary staff at the vendor and used to determine that all foxes had negative results for rVNA before shipment to our facility. Foxes were housed for 120 days in an animal biosafety level-2 facility at the investigator’s facility. Foxes were housed in indoor-outdoor runs (1.1 m in length × 0.8 m in width) with a climate-controlled block wall pens (4.9 m in length × 0.8 m in width) with a heated floor (used in winter) with a chain link door and chain link roof. Gray foxes were fed a 1:1 mix of diets formulated for omnivoresb and dogs.c Methods were used to enrich the diet and promote consumption. Foxes received peeled hard boiled eggs twice weekly, which were alternated with 1/3 can of a beef or a chicken dog food that was mixed with the regular diet. Animal use protocols were approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

RABV vaccine

The RABV PBV vaccine was produced as described elsewhere.18 Briefly, RABV strain ERA was attenuated by use of a reverse genetics system.27,28 Amino acid 333 in the glycoprotein was altered at the corresponding nucleotide positions in the glycoprotein gene by use of site-directed mutagenesis.29–31 The recovered virus, ERAG333, was mixed with preservation solution (formulated with or without alginate) and dried via the PBV process. Vaccines were suspended in sterile mineral oil and stored with a desiccant for up to 65 days at 22° ± 4°C in the dark.

Experimental procedures

Foxes were arbitrarily allocated into 3 groups, and vaccine was endoscopically placed in the duodenum of all groups (day 0). Group 1 (2 males and 1 female) received 1 mL of nonencapsulated RABV PBV (mean ± SD; 5.2 ± 0.09 log10 ffu/mL), group 2 (3 females) received 1 mL of alginate-encapsulated RABV PBV (4.3 ± 0.2 log10 ffu/mL), and group 3 (2 males) received 1 mL of RABV ERAG333 (from stock stored at −80°C; 8.0 ± 0.2 log10 ffu/mL).

Food and water was withheld from all foxes for 24 hours prior to endoscopy to allow ingesta to pass from the stomach and proximal portions of the intestines, minimize the potential of regurgitation during anesthesia, reduce the potential for impeding visual video monitoring, and reduce the potential of obstruction of the endoscope and thus placement of the vaccine. Food and water were withheld for 24 hours prior to scheduled endoscopy for 1 fox in group 3; however, endoscopy could not be performed at that time. Because the period for withholding of food and water from animals should not exceed 24 hours, this fox received food and subsequently had ingesta in its stomach and duodenum at the time of vaccine placement (24 hours after the originally scheduled endoscopy).

Each fox was restrained with a catchpole, and anesthesia was induced by administration of a combination productd that contained tiletamine HCl–zolazepam HCl (9 mg/kg, IM). Once anesthetic induction was confirmed, each fox received atropine (0.04 mg/kg, IM) to reduce salivation, and an appropriately sized endotracheal tube with inflatable cuffe was placed and secured. Isoflurane (2% to 4%) was administered to establish a surgical plane of anesthesia. Foxes were positioned in left lateral recumbency to promote passage of the endoscope into the duodenum. A flexible endoscopef was passed through the mouth and into the esophagus. Video monitoring confirmed key anatomic landmarks from the oral cavity into the esophagus, stomach, pylorus, and opening of the proximal portion of the duodenum. Approximately 1 mL of vaccine was placed in the biopsy channel. The vaccine was delivered through the channel by the use of air, and the channel then was flushed with sterile water. Once placement of the vaccine was confirmed, the endoscope was slowly removed. Foxes were monitored constantly until they had recovered from anesthesia. The endoscope was washed and disinfected before use in the subsequent fox.

Collection of data and samples

Foxes were purchased and arrived at our facility (day −90). After a 14-day acclimation period was completed, a health examination was performed on each fox (day −76). Body weight was measured on days −90, −76, 0, 7, 14, 21, and 28. A blood sample (2 mL) was collected from each fox immediately before vaccine placement on day 0 and on days, 7, 14, 21, and 28 after vaccination. Samples were used to determine the rVNA titer by use of a rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test.32 Food and water were withheld from the foxes for 24 hours prior to sedation to avoid regurgitation and possible aspiration. Foxes were restrained with a catchpole and sedated by administration of a combination product that contained tiletamine HCl–zolazepam HCl (< 9 mg/kg, IM). An area on the ventral aspect of the neck or forelimb of the sedated foxes was shaved and scrubbed with alcohol, and blood samples were collected from a jugular or cephalic vein by use of a 21-gauge (or smaller gauge) needle. Saliva samples were obtained from the sedated foxes at the same time as collection of the blood samples. A sterile cotton swab was inserted into the oral cavity, and oral swab specimens were used for virus detection with a standard RT-PCR assay for RABV nucleocapsid protein gene.33,34 Foxes were monitored constantly until they had recovered from sedation.

Necropsy

On day 28, foxes were restrained with a catchpole, anesthetized by administration of tiletamine HCl–zolazepam HCl (9 mg/kg, IM), and euthanized by intracardiac administration of 2 mL of pentobarbital sodium–phenytoin sodium.g Euthanasia was confirmed as a lack of respiratory and cardiac function via stethoscopic auscultation, and 1 mL of CSF was then collected. Necropsy was performed on each fox, and samples of the duodenum, salivary glands, heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, spleen, lumbar spinal cord, and brain stem were collected. The RABV antigen was detected by use of direct fluorescent antibody testing or immunohistochemical staining, and RABV RNA was detected by use of an RT-PCR assay.33–35

Statistical analysis

Seroconversion was designated as increase in rVNA titers to > 0.1 U/mL. Two-way Anova (alpha = 0.05) with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons (alpha = 0.05, CI = 95%) was performed to compare results for mean rVNA over time, among the 3 groups. Values were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Animals

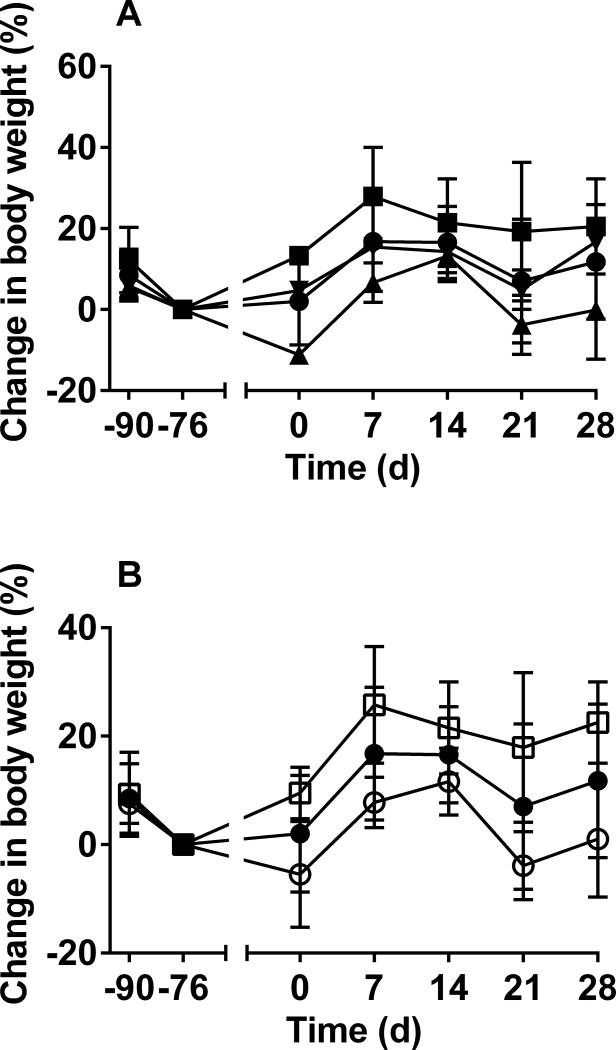

All foxes were in good condition and remained healthy throughout the experimental period. Overall, the mean body weight of all the groups increased; however, males gained more weight than did females (Figure 1). All foxes recovered well from endoscopic placement of the vaccine, and the procedures did not result in inappetence. Foxes were observed daily, and no clinical signs of rabies were observed in any animal.

Figure 1.

Mean ± SD percentage change in body weight of gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) administered RABV vaccine on the basis of group (A) and on the basis of sex (B). Body weight was obtained at the time of arrival at our facility (day −90), at a health examination performed after a 14-day acclimation period (day −76), before endoscopic delivery of vaccine (day 0), and at the time of blood collection on days 7, 14, 21, and 28. Mean and SD were calculated for each group by the percentage change for each fox calculated by use of the body weight obtained on day −76 as the denominator. In panel A, results are reported for all 8 foxes (black circles), 3 foxes (2 males and 1 female) that received 1 mL of nonencapsulated RABV PBV (mean ± SD; 5.2 ± 0.09 log10 ffu/mL; group 1 [black squares]), 3 foxes (3 females) that received 1 mL of alginate-encapsulated RABV PBV (4.3 ± 0.2 log10 ffu/mL; group 2 [black triangles]), and 2 foxes (2 males) that received 1 mL of RABV ERAG333 (8.0 ± 0.2 log10 ffu/mL; group 3 [inverted black triangles]). In panel B, results are reported for all 8 foxes (black circles), the 4 female foxes (white circles), and the 4 male foxes (white squares).

Vaccination response

Values for rVNA did not differ significantly among the groups. Two of 3 foxes of group 1 (received nonencapsulated RABV PBV) seroconverted (titer > 0.1 U/mL) by day 14, and titers continued to increase until the end of the study. The titer of both animals on day 28 was 1.2 U/ml. One of 2 foxes of group 3 (received RABV ERAG333) seroconverted by day 14, and the titer of that animal continued to increase until the end of the study (titer on day 28 was 1.6 U/ml). Administration of both nonencapsulated RABV PBV and ERAG333 induced similar titers on day 28. The other fox of group 3 may have failed to seroconvert because of bile inactivation of the live RABV because this fox had food in its stomach at the time of endoscopy (see Experimental procedures in Material and Methods). None of the foxes of group 2 (alginate-encapsulated RABV PBV) seroconverted. Some weak virus neutralization was observed in 1 fox of group 2. The titer on days, 7, 14, 21 and 28 was 0.07, 0.06, < 0.05, and 0.1 U/ml, respectively.

Examination of oral swab specimens obtained during the study was performed. No RABV RNA was detected on any day of the study.

Necropsy

None of the foxes had evidence of rVNA in the CSF on day 28. None of the foxes had evidence of RABV infection in the lumbar spinal cord or brain stem on day 28, as determined by use of direct fluorescent antibody staining. Finally, RABV RNA was not detected in any tissues obtained from any of the foxes on day 28.

Discussion

Results for the study reported here indicated that the response to vaccination was attributable to delivery of live RABV vaccine to the duodenal mucosa of gray foxes. On the basis of results for the 3 foxes that seroconverted, geometric mean ± SD titer increased from 0.28 ± 0.03 U/mL on day 14 to 1.3 ± 0.2 U/mL on day 28. The rVNA did not differ significantly among the groups. However, the results were clinically relevant because RABV PBV vaccine placed endoscopically in the duodenum induced rabies virus neutralizing antibody titers greater than the World Organization for Animal Health recommended value of 0.5 U/mL.36 On the basis of the present proof-of-concept study, thermostable RABV PBV may have use as part of oral vaccination programs in the future.

The RABV PBV vaccines were suspended in sterile mineral oil, whereas, the control RABV was delivered in an aqueous solution. Mineral oil may have protected the nonencapsulated RABV PBV from bile or acted as an adjuvant to allow the virus to persist at the target site and increase the chances of activating an immune response. Future formulations should include bile inhibitors, mineral oil, or both.

The alginate-encapsulated vaccine failed to stimulate an immune response. This formulation of the vaccine resulted in a lower mean ± SD RABV titer, compared with the mean titer for the nonencapsulated vaccine and control RABV, which may not have been sufficient to stimulate an immune response. By comparison, other studies18,30,37 with live-attenuated RABV vaccines involved formulations at 4.4 log10 ffu/mL to 9.3 log10 ffu/mL. Because the vaccine was a live-attenuated virus, viral replication should have negated any differences in the initial titer. Previous attempts23,28 to target the intestinal mucosa by use of alginate-encapsulated vaccines have been successful. Delivery of the alginate-encapsulated vaccine through the biopsy channel may have been hindered because the encapsulated vaccine was more viscous than the nonencapsulated vaccine. Concerns about dose and the problem of inactivation by bile could be resolved by use of a capsulated vaccine that is designed to target the intestinal mucosa and is delivered orally to animals in their regular diet.

Although the present study was not designed to detect viral shedding, which may occur within the first 48 hours after oral vaccination,39,40 we did not detect viral shedding in saliva samples obtained at the times of blood collection. Any localized viral replication was cleared by day 28 such that no evidence of infection could be detected in the tissue samples collected during necropsy. None of the foxes developed rabies, and all nerve tissue and CSF obtained on day 28 had negative results when tested for RABV. Future studies to examine possible viral shedding in feces and to evaluate oral delivery methods could be completed in red foxes because this is an established and more accessible animal used for rabies research. Overall, the results of the study reported here added to the evidence that RABV PBV may be formulated into a vaccine for domestic or wild animals and supported future testing of the desired method of delivery in target species.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Cynthia Cary, Dr. Nicole Lukovsky Akhsanov, and Ryan Johnson for technical assistance.

Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grant No. R44AI080035-3 awarded to Dr. Bronshtein).

Supported in part by a contract between Solution One Industries, Inc. and CDC.

Supported in part by an appointment to the Research Participation Program at CDC administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and CDC.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ERA

Evelyn-Rokitnicki-Abelseth

- ERAG

Evelyn-Rokitnicki-Abelseth glycoprotein

- ffu

Focus-forming unit

- PBV

Preservation by vaporization

- RABV

Rabies virus

- RT

Reverse transcriptase

- rVNA

Rabies virus neutralizing antibodies

Footnotes

Presented in part in abstract form at the 25th International Conference on Rabies in the Americas, Cancún, México, October, 2014.

Use of trade names and commercial sources are for identification only and do not imply endorsement by the US government. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of their institutions.

Ruby’s Farm, New Sharon, Iowa.

Mazuri Omnivore-Zoo Feed ‘A’ 5635, Purina Mills International, St Louis, Mo.

Lab Diet Laboratory Canine Diet 5006, Purina Mills International, St Louis, Mo.

Zoetis, Florham Park, NJ.

Vedco, St Joseph, Mo.

Olympus America, Center Valley, Pa.

Merck & Co, Kenilworth, NJ.

References

- 1.Knobel DL, Cleaveland S, Coleman PG, et al. Re-evaluating the burden of rabies in Africa and Asia. Bull WHO. 2005;83:360–368. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wunner WH, Briggs DJ. Rabies in the 21 century. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson A, Shwiff SA. The cost of canine rabies on four continents. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2015;62:446–452. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. WHO expert consultation on rabies second report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanton JD, Bowden NY, Eidson M, et al. Rabies postexposure prophylaxis, New York, 1995–2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1921–1927. doi: 10.3201/eid1112.041278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of a reduced (4-dose) vaccine schedule for postexposure prophylaxis to prevent human rabies: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR. 2010;59:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durrheim DN, Rees H, Briggs DJ, et al. Mass vaccination of dogs, control of canine populations and post-exposure vaccination—necessary but not sufficient for achieving childhood rabies elimination. Trop Med Int Health. 2015;20:682–684. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma X, Blanton JD, Rathbun SL, et al. Time series analysis of the impact of oral vaccination on raccoon rabies in West Virginia, 1990–2007. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10:801–809. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cliquet F, Picard-Meyer E, Robardet E. Rabies in Europe: what are the risks? Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2014;12:905–908. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2014.921570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muller TF, Schroder R, Wysocki P, et al. Spatio-temporal use of oral rabies vaccines in fox rabies elimination programmes in Europe. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brochier B, Thomas I, Bauduin B, et al. Use of a vaccinia-rabies recombinant virus for the oral vaccination of foxes against rabies. Vaccine. 1990;8:101–104. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(90)90129-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawson KF, Bachmann P. Stability of attenuated live virus rabies vaccine in baits targeted to wild foxes under operational conditions. Can Vet J. 2001;42:368–374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reculard P. Cell-culture vaccines for veterinary use. In: Meslin FX, Kaplan MM, Koprowski H, editors. Laboratory techniques in rabies. 4. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. pp. 314–323. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montagnon B, Fanget B. Purified Vero cell vaccine for humans. In: Meslin FX, Kaplan MM, Koprowski H, editors. Laboratory techniques in rabies. 4. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. pp. 285–289. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barth R, Franke V. Purified chick-embryo cell vaccine for humans. In: Meslin FX, Kaplan MM, Koprowski H, editors. Laboratory techniques in rabies. 4. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. pp. 290–296. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith TG, Ellison JA, Ma X, et al. An electrochemiluminescence assay for analysis of rabies virus glycoprotein content in rabies vaccines. Vaccine. 2013;31:3333–3338. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith TG, Siirin M, Wu X, et al. Rabies vaccine preserved by vaporization is thermostable and immunogenic. Vaccine. 2015;33:2203–2206. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bronshtein V. Preservation by foam formulation. Pharm Technol. 2004;28:86–92. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bronshtein V, inventor. Universal Stabilization Technologies Inc, assignee. Preservation by vaporization. 2008/0229609. US patent. 2008 Sep 25;

- 21.Lawson KF, Johnston DH, Patterson JM, et al. Immunization of foxes by the intestinal route using an inactivated rabies vaccine. Can J Vet Res. 1989;53:56–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rupprecht CE, Dietzschold B, Campbell JB, et al. Consideration of inactivated rabies vaccines as oral immunogens of wild carnivores. J Wildl Dis. 1992;28:629–635. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-28.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim B, Bowersock T, Griebel P, et al. Mucosal immune responses following oral immunization with rotavirus antigens encapsulated in alginate microspheres. J Control Release. 2002;85:191–202. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00280-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Texas Department of State Health Services website. Oral rabies vaccination program (ORVP) [Accessed Aug 3, 2016]; Available at: www.dshs.texas.gov/idcu/disease/rabies/orvp/

- 25.Sidwa TJ, Wilson PJ, Moore GM, et al. Evaluation of oral rabies vaccination programs for control of rabies epizootics in coyotes and gray foxes: 1995–2003. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;227:785–792. doi: 10.2460/javma.2005.227.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slate D, Algeo TP, Nelson KM, et al. Oral rabies vaccination in North America: opportunities, complexities, and challenges. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abelseth MK. An attenuated rabies vaccine for domestic animals produced in tissue culture. Can Vet J. 1964;5:279–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu X, Rupprecht CE. Glycoprotein gene relocation in rabies virus. Virus Res. 2008;131:95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dietzschold B, Wunner WH, Wiktor TJ, et al. Characterization of an antigenic determinant of the glycoprotein that correlates with pathogenicity of rabies virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:70–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu X, Franka R, Henderson H, et al. Live attenuated rabies virus co-infected with street rabies virus protects animals against rabies. Vaccine. 2011;29:4195–4201. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu X, Gong X, Foley HD, et al. Both viral transcription and replication are reduced when the rabies virus nucleoprotein is not phosphorylated. J Virol. 2002;76:4153–4161. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.9.4153-4161.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith JS, Yager PA, Baer GM. A rapid reproducible test for determining rabies neutralizing antibody. Bull WHO. 1973;48:535–541. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trimarchi CV, Nadin-Davis SA. Diagnostic evaluation. In: Jackson AC, Wunner WH, editors. Rabies. 2. Oxford, England: Academic Press; 2007. pp. 411–469. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franka R, Wu X, Jackson FR, et al. Rabies virus pathogenesis in relationship to intervention with inactivated and attenuated rabies vaccines. Vaccine. 2009;27:7149–7155. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dean DJ, Abelseth MK, Atanasiu P. The fluorescent antibody test. In: Meslin FX, Kaplan MM, Koprowski H, editors. Laboratory techniques in rabies. 4. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. pp. 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Organisation for Animal Health. OIE terrestrial manual. Paris: World Organisation for Animal Health; 2013. Rabies; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu X, Smith TG, Franka R, et al. The feasibility of rabies virus-vectored immunocontraception in a mouse model. Trials Vaccinol. 2014;3:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nechaeva EA, Varaksin N, Ryabicheva T, et al. Approaches to development of microencapsulated form of the live measles vaccine. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;944:180–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knowles MK, Nadin-Davis SA, Sheen M, et al. Safety studies on an adenovirus recombinant vaccine for rabies (AdRG1.3-ONRAB) in target and non-target species. Vaccine. 2009;27:6619–6626. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orciari LA, Niezgoda M, Hanlon CA, et al. Rapid clearance of SAG-2 rabies virus from dogs after oral vaccination. Vaccine. 2001;19:4511–4518. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]