Abstract

Background

Increased prevalence of overweight and obesity among Appalachian residents may contribute to increased cancer rates in this region. This manuscript describes the design, components, and participant baseline characteristics of a faith-based study to decrease overweight and obesity among Appalachian residents.

Methods

A group randomized study design was used to assign 13 churches to an intervention to reduce overweight and obesity (Walk by Faith) and 15 churches to a cancer screening intervention (Ribbons of Faith). Church members with a body mass index (BMI) ≥25 were recruited from these churches in Appalachian counties in five states to participate in the study. A standard protocol was used to measure participant characteristics at baseline. The same protocol will be followed to obtain measurements after completion of the active intervention phase (12 months) and the sustainability phase (24 months). Primary outcome is change in BMI from baseline to 12 months. Secondary outcomes include changes in blood pressure, waist-to-hip ratio, and fruit and vegetable consumption, as well as intervention sustainability.

Results

Church members (n = 664) from 28 churches enrolled in the study. At baseline 64.3% of the participants were obese (BMI ≥30), less than half (41.6%) reported regular exercise, and 85.5% reported consuming less than 5 servings of fruits and vegetables per day.

Conclusions

Church members recruited to participate in a faith-based study across the Appalachian region reported high rates of unhealthy behaviors. We have demonstrated the feasibility of developing and recruiting participants to a faith-based intervention aimed at improving diet and increasing exercise among underserved populations.

Keywords: Cancer, Appalachian region, Health disparities, Obesity, Diet, Exercise

1. Introduction

Appalachia, an Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC)-designated region along the Appalachian mountains, is home to nearly 25 million residents (8% of the United States (U.S.) population) [1]. Appalachian residents are socioeconomically disadvantaged and experience more geographic isolation, higher poverty rates, lower health insurance rates, lower education levels, and less health care access than non-Appalachian residents [2]. These factors contribute to disparities in cancer risk factors, incidence, mortality and survivorship [3,4]. The leading cause of death in the U.S. is cardiovascular disease [5], however in Appalachia, cancer is the leading cause of death [3]. Cancer disparities among Appalachians compared to the U.S. are well documented [3,6] as are higher rates of modifiable behavioral risk factors that influence cancer risk including overweight and obesity, physical inactivity, tobacco use, and inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption [7–9]. In opposition to the increased cancer burden, there are many positive characteristics among Appalachians, such as resilience and strong family, community, and religious ties.

The National Cancer Institute funded the Appalachia Community Cancer Network (ACCN) to increase awareness and promotion of cancer prevention and control activities in Appalachia. ACCN, headquartered at the University of Kentucky (UK), is a collaborative effort of UK, The Ohio State University (OSU), The Pennsylvania State University (PSU), Virginia Tech (VT), and West Virginia University (WVU). Because community members' perspectives are important when developing, implementing, and evaluating interventions to address cancer disparities [10–14], ACCN partners have established strong networks of community partners to increase the capacity for cancer prevention and control research by using community-engaged strategies and community based participatory research (CBPR) practices [15].

Building on the strengths of this community-academic partnership, ACCN academic investigators and community partners collaborated with faith-based organizations in a cancer prevention research study to reduce the prevalence of overweight and obesity. Previous faith-based programs have demonstrated increased knowledge of disease, willingness to engage in primary prevention activities, improved cancer screening behaviors and readiness to change [16–18]. However, few outcomes-oriented faith-based programs have been developed in collaboration with community partners specifically for Appalachian residents [16,17,19].

To decrease overweight and obesity among Appalachian residents, CBPR principles were used to develop an intervention entitled Walk by Faith (WbF). An existing faith-based program, “Healthy Body, Healthy Spirit” (HBHS) [20], was used as the guiding framework for WbF. The WbF program was piloted among 191 church members from seven Ohio Appalachian churches (2007–2008). The six-week program was completed by 144 (75.4%) participants who demonstrated an 8.5% increase in weekly fruit and vegetable servings consumed and an 8.8% increase in weekly intake of 8 oz glasses of water. The pilot study findings and participants' suggestions were used to modify WbF for the current study, which included churches in five Appalachian states. Investigators hypothesize that change in weight from baseline to one year follow-up among intervention participants will be greater than among comparison participants, such that the differential change will be negative on average. The purpose of this paper is to describe the study design, intervention components, and baseline characteristics of the participants in the full study.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

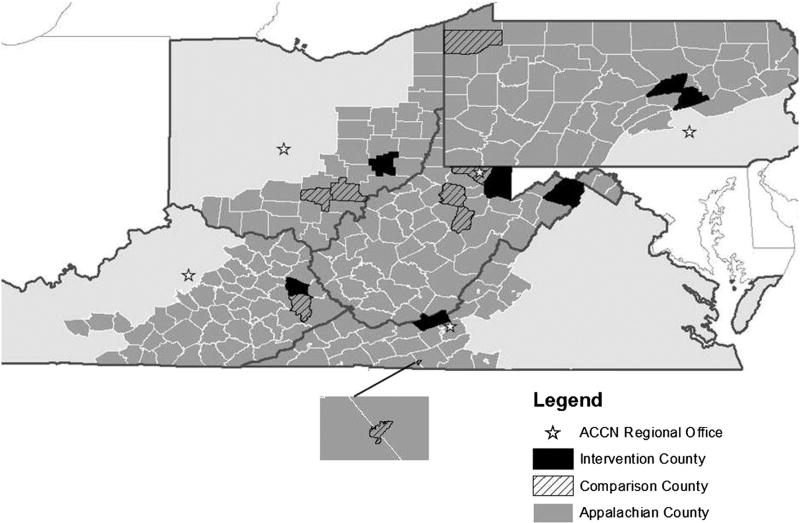

The study used a group-randomized design with churches assigned to the WbF intervention or to a comparison intervention that consisted of a cancer screening education intervention entitled Ribbons of Faith (RoF). Geographic region (county or group of counties) was the unit of randomization, with each state having one region randomized to WbF and one to RoF. Across the five states, a total of 13 churches were assigned to the WbF intervention and 15 churches were assigned to the RoF intervention. Randomization occurred prior to baseline data collection and was stratified by state. One region within each state was randomly assigned to WbF and one region to RoF. The locations of the counties by treatment arm and of the ACCN regional offices are highlighted in Fig. 1. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of UK, OSU, PSU, VT and WVU, with OSU serving as the study's coordinating center, leading protocol development, staff training and data collection.

Fig. 1.

Map of Appalachian study region.

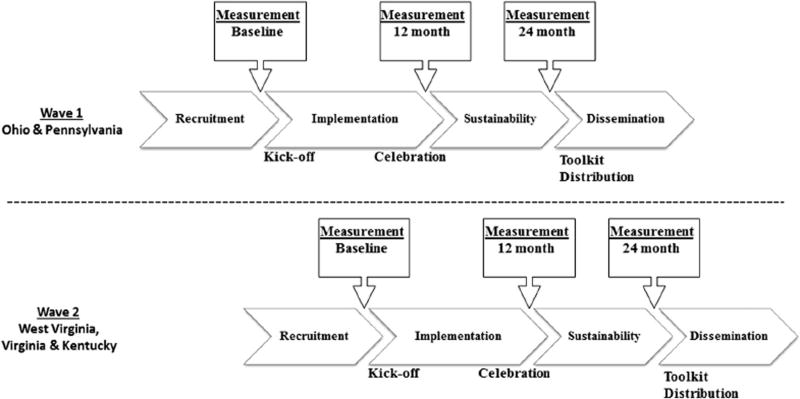

The study was conducted in two waves; OSU and PSU served as the vanguard group with participants recruited from January 2012 until September 2012 (Wave 1). Lessons learned from Wave 1 recruitment and data collection activities were then used to modify and refine recruitment strategies used by WVU, VT and UK for recruitment from November 2012 through October 2013 (Wave 2). The overall study design and timeline are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Study design and timeline.

2.2. Intervention components

2.2.1. Intervention: Walk by Faith (WbF)

The WbF intervention activities focused on increasing physical activity and changing unhealthy dietary behaviors, and were aimed at the organizational level (church) and the individual level (church members). At least one volunteer, often nominated by church leadership, was recruited and trained to be the church navigator in each church. The navigator in each church was trained by the project manager of that state. The church navigator's role was to facilitate intervention activities and assist participants with the intervention components, as needed. A study interventionist from each local community was hired from the local community and trained to assist WbF participants to develop wellness plans based on stages of change, set short and long-term diet and physical activity goals, and to meet with participants about their progress toward reaching their goals. Interventionists from each state came to OSU for a two-day centralized training session prior to the start of the study and web-based training will occur annually.

2.2.1.1. Organization level

At the organizational level, the framework of the WbF intervention is in line with the Social Determinants of Health, where a social ecological perspective addressed components of the intervention including change in church policies, structures, and community resources [21]. The church navigators, study interventionist, community partners, and regional study staff collaborated to identify ways to support healthy eating, increase physical activity levels, and plan church events. All churches were provided with touchscreen computers, printers, and high-speed internet access. Computers provided access to the study's interactive website, Faithfully Living Well (FLW), and other online resources to improve healthy eating and increase physical activity. The FLW was culturally adapted so that each church had photographs of their church and local community, a church-specific forum, and local resources to promote health (e.g. local farmers markets, etc.). Examples of intervention activities at the church level included conducting healthy cooking demonstrations with locally available foods and recipe competitions, providing healthy food choices at church events, holding church walks using local trails, and conducting walking competitions.

2.2.1.2. Individual level

At the individual level, WbF is based on the constructs of the Social Cognitive Theory [22], increasing knowledge and awareness of healthy behaviors, promoting self-efficacy to increase physical activity and improve diet by providing resources to the participants, collective efficacy with church member activities, and facilitators within the churches (volunteer navigators) who acted as role models. Participants were provided access to the intervention website, pedometers, diet and physical activity journals, nutrition guides, an interventionist to assist with goal setting, and monthly education sessions.

Educational sessions were held monthly and many had topics related to a specific month or season, such as keeping New Year's resolutions, eating healthy during the holidays, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle during summer vacations. Study-related personnel secured promotional offers and donations from local businesses and organizations to be used as incentives on FLW to encourage participants to improve healthy eating or increase their physical activity levels. Participants used the interactive website targeted to their county to track their progress over the 12 month intervention phase. Reward points could be earned by participants based on completed activities such as daily logging onto the website, uploading pedometer step data, recording current weight, using the activity tracker, setting and completing weekly goals, completing short dietary surveys which provide tailored feedback, posting to forums, submitting healthy recipes to share, commenting on health articles, and attending monthly church activities. Reward points were redeemed for promotional offers obtained from within each participant's community.

2.2.2. Comparison intervention: Ribbons of Faith (RoF)

The RoF intervention implemented in comparison churches focused on improving cancer screening knowledge and promoting cancer screening behaviors as recommended by the American Cancer Society (ACS) [23]. At least one volunteer was recruited and trained to be the church navigator in each RoF church to facilitate intervention activities aimed at the organizational and individual levels.

2.2.2.1. Organization level

The church navigators, community partners, and regional study staff collaborated to identify ways to promote cancer screening and plan church events. Examples included holding interactive educational sessions, a health fair, and producing and providing cancer education inserts for the church bulletins. Cultural adaptation for the RoF program included providing local resources for church members to complete cancer screening tests, providing names and locations of local providers, and having local community members and agencies serve as session speakers and participate in health fairs. All churches were provided touchscreen computers, printers, and highspeed internet access so church members could access cancer screening information on the internet. In addition, standardized PowerPoint presentations that focused on different cancer risk and screening topics were provided to each church.

2.2.2.2. Individual level

At the individual level, RoF is based on several important constructs of the Social Cognitive Theory [22]. Education sessions focused on improving self-efficacy to complete cancer screening tests, and to provide information to support behavioral change (e.g. social support). In monthly education sessions at each RoF church, participants were provided with cancer screening educational materials that included age-appropriate cancer screening recommendations for cervical, breast, colorectal, prostate, testicular, and skin cancers. These education sessions were held during particular cancer awareness months whenever possible. Participants could ask questions about cancer risk and cancer screening at the educational sessions and participants were encouraged to complete age-appropriate recommended cancer screening tests at all RoF church events.

2.3. Church recruitment

Researchers collaborated with existing partners, coalition members, and Community Advisory Board members to identify potential churches for the project from the churches in each study county that had at least 80 active congregation members. Telephone calls were made to identified churches to describe the project and assess interest. If a church was interested in participating, study staff would visit the church to discuss the project in more detail with the church leader or council members. Once a church agreed to participate, the church leader and regional principal investigator (PI) signed a memorandum of understanding and started the process of identifying church navigators and scheduling information sessions for the congregation members.

2.4. Participant recruitment

WbF and RoF interventions were introduced to the respective churches at information sessions which were announced from the pulpit at church services and advertised in church bulletins. The regional PIs and staff members participated in the information sessions, providing a review of cancer statistics in Appalachia and a brief overview of the intervention (either WbF or RoF) including eligibility criteria, surveys, measurements to be collected, participant time commitment, and the consent process. Following each information session, interested church members were encouraged to meet with study staff or schedule to meet with a field interviewer hired from within the community to discuss the study in more detail, be screened for eligibility, provide written informed consent, and complete biometric measurements with available staff. Eligibility criteria included: being at least 18 years of age, attending services at a participating church at least four times in the past two months, being able to understand and read English, cognitively able to provide informed consent, being a resident of an Appalachian county as indicated by the ARC's designation [1], willing to use a computer, weighing less than 400 lb, and having a BMI of at least 25. Exclusion criteria included: residing in a nursing facility or residential home, planning to move away from the study area, dietary restrictions prescribed for weight-loss or part of a formal weight-loss program, and, if female, being pregnant, breastfeeding or less than 9 months post-partum or planning to become pregnant during study period. Modified Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) items were used to identify conditions that would require medical clearance [24]. The consent process was completed individually with study staff leading a discussion of the details within the consent form and both parties signing the document after the discussion.

2.5. Data collection

2.5.1. Community assessments

Prior to the start of individual level recruitment, the study team collected community data including county-level data for the study counties. The FY2012 ARC County Economic Status and Distressed Areas in Appalachia reports were used to determine ARC classifications, population sizes, per capita market income, poverty rate, and unemployment rates for each participating county. By comparing these factors to comparable data for all U.S. counties, Appalachian counties have been classified as distressed, at-risk, transitional, competitive, or at attainment [25].

In addition, a standard form created by the investigators was used to assess community resources available to participants in WbF and RoF counties. Resources assessed included locations where participants could exercise (e.g., public parks and recreational centers); purchase fresh fruits and vegetables (e.g., grocery stores and farmers' markets); access healthcare and obtain healthy lifestyle information (e.g., hospitals, county health departments, local nutritionists or physical activity trainers); access the internet (e.g., library); and receive transportation assistance (e.g., taxi and shuttle services). This information, along with other intervention materials, was shared with participants at the kick-off event.

2.5.2. Church assessments

Researchers used a standard church profile form to conduct the church assessment to collect information regarding denomination, fellowship activities, health-related groups and events, congregation size, estimation of regular attendance, worship times, and physical facilities. These assessments were used to determine the best locations to place the church computer and printer, to identify rooms available to conduct educational sessions and data collection, and to evaluate kitchen space and equipment needed to organize cooking demonstrations or prepare healthy meals.

2.5.3. Participant data collection

Prior to the start of the intervention, participants completed an in-person data collection session, a telephone interview, and completed self-administered surveys (computer assisted interview and take home survey) using validated questionnaires. Similar assessments will be repeated at 12 and 24 months. Biometric data were collected at the church by field staff trained centrally by the coordinating center using a standardized protocol. Trained interviewers completed telephone surveys and provided assistance with the computer-based surveys and take-home surveys, if needed. Measures, collection methods, and time points for data collection are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Measures, collection methods, and assessment time points.

| Collection method | Measure [reference] | Time points

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12-mo | 24-mo | ||

| In-person | Height [26] | ● | ||

| Blood pressure [26,56,57] | ● | ● | ● | |

| Body image [27] | ● | ● | ● | |

| Waist/hip measurement [26,58] | ● | ● | ● | |

| Weight [26] | ● | ● | ● | |

| Phone interview | Demographics | ● | ● | ● |

| Cancer screening | ● | ● | ● | |

| Tobacco Use [28] | ● | ● | ● | |

| Depression (CES-D 20) [29] | ● | ● | ● | |

| Loneliness [30] | ● | ● | ● | |

| Social support (MSPSS) [31] | ● | ● | ● | |

| Stage of change: diet [32] | ● | ● | ● | |

| Stage of change: exercise [32–34] | ● | ● | ● | |

| Paper survey | Household composition | ● | ● | ● |

| Socioeconomic status | ● | ● | ● | |

| Health literacy [36] | ● | ● | ● | |

| Cancer history | ● | ● | ● | |

| Sleep habits [37] | ● | ● | ● | |

| Self-Efficacy: diet [38] | WbF | WbF | WbF | |

| Self-efficacy: exercise [39,40] | WbF | WbF | WbF | |

| Social support: diet [41] | WbF | WbF | WbF | |

| Social support: exercise [41] | WbF | WbF | WbF | |

| Web survey | Food frequency [44] | ● | ● | ● |

| Physical activity [42,43] | ● | ● | ● | |

| Healthy lifestyle barriers | WbF | WbF | WbF | |

CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression; MSPSS: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; WbF: Walk by Faith.

2.5.3.1. In-person session

Biometric measurements collected were standardized using the PhenX Toolkit [26] including height (barefoot and only at baseline), weight, blood pressure, and waist and hip circumference. PhenX Toolkit protocols for blood pressure and waist and hip measurements were modified slightly in order to better accommodate participants wearing restrictive attire. Measurements were collected using calibrated digital scales (weight), digital sphygmomanometers (blood pressure), Gulick spring-loaded tape measures (hip and waist girth), and stadiometers to measure height. In addition, participants answered four body image questions using body silhouettes at the time of the in-person session [27]. These measurements took approximately 30 min for each participant to complete.

2.5.3.2. Telephone interview

The following information was collected during the telephone interview: demographic characteristics (age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, marital status, occupation, household income, health insurance, healthcare use, and Appalachian and rural self-identity), cancer screening history, tobacco use history [28], depression [29], loneliness [30], social support [31], and stages of change for diet [32] and exercise [32–34]. Telephone interview data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) software [35], a secure, web-based data capture application hosted at The Ohio State University. Phone calls lasted an average of 15 min.

2.5.4. Paper-based surveys

Information collected by paper surveys included household composition, socioeconomic information, health literacy [36], personal and family cancer history, and sleep habits [37]. Additionally, WbF participants completed questionnaires about self-efficacy for diet [38] and exercise [39,40] and social support for diet [41] and exercise [41]. Data were entered into REDCap [35] for management. Completion of the paper surveys took about 10 min.

2.5.4.1. Web-based surveys

Web-based surveys completed by all participants included a web-based food frequency questionnaire and a physical activity survey developed by Viocare, Inc., a privately-held health and wellness systems company [44]. These validated, online assessments allow for detailed analysis of energy output and daily dietary intake [42–44]. In addition, barriers to a healthy lifestyle were also collected from WbF participants and responses were used to facilitate intervention counseling. These web-based surveys were completed at a follow-up appointment at the church and took 30–45 min to complete using a touchscreen PC provided by the study to the church; a project staff person was present to assist participants if needed.

2.5.5. Process evaluation

The following process evaluation is planned during the study period to ensure intervention fidelity. Pre- and post-tests at each education session, participant satisfaction with the program at 6 and 12 months, church leader and church navigator satisfaction surveys will be conducted at regular intervals. Project managers plan on having monthly phone calls or face-to-face meetings with the church navigators to gain information about events held, attendance at events, plans for future events, and to strategize on how to increase engagement of participants. In addition, WbF participants can use the intervention website to report any concerns about the program.

2.5.6. Follow-up assessments

The 12-month active intervention phase will be followed by at least one year of a sustainability phase in each church. During the sustainability phase, volunteer church members are encouraged to plan, hold and report on program-related activities such as walks and demonstrations without assistance from study staff.

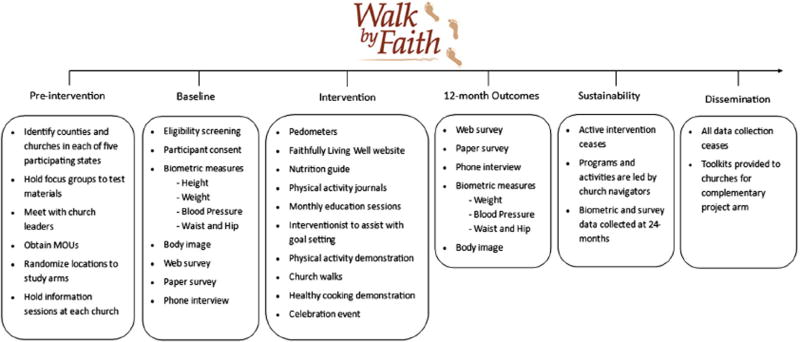

Measurements to be collected at the annual follow-up assessments include biometric measurements (except height), food frequency questionnaire, physical activity survey, and a paper and telephone survey to assess sociodemographic- and health-related changes, as summarized in Fig. 3. Follow-up assessments at the end of the study will be collected within one month of the final intervention activity.

Fig. 3.

Activities and components of the Walk by Faith Intervention.

2.6. Sample size

Using a power calculation equation [45] modified to accommodate tests based on two means, we determined the number of church members within each region needed for adequate power to detect a difference in change in body mass index (BMI) between the intervention and comparisons regions at 12 months. The parameters for sample size determination were based on values reported in the literature for exercise-only and diet-only worksite interventions [46], with the expectation of a larger effect size in our study given use of a combined diet and exercise intervention. We chose a conservative effect size of 0.51 (change of 1.52, standard deviation of 3.0), accounting for potential increased variability for change in the setting of a worksite versus a church. We assumed an intra-class correlation (ICC, correlation between responses from any two church members from the same region) of 0.05, which is slightly larger than the largest value used in the design of seven different similar (worksite) intervention studies [47]. Based on these considerations and accounting for 20% attrition of church members at 12 months, a sample of 10 regions (two in each state for five per intervention arm) with 100 church members per region (80 evaluable at 12 months accounting for a 20% attrition rate), will yield 80% power to detect our hypothesized effect (two-sided, α = 0.05).

2.7. Analysis plan

The primary outcome is change in BMI from baseline to 12 months. Secondary outcomes include changes in blood pressure, waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), and self-report of fruit and vegetable consumption. In order to account for the group randomized design and hierarchical nature of the data, a linear mixed model will be used in our analysis [48–50] to model the BMI outcome at 12 months. Fixed effects will include baseline BMI, treatment group and any covariates identified a priori, as well as a random effect for region. Covariates will be selected prior to fitting the primary models using a linear mixed model fit only to the baseline data. A backwards selection technique (performed at α = 0.1) will then be used to select the important covariates for our primary models. Multiple imputation will be used to impute missing 12-month BMI measurements.

Sustainability of the intervention will be evaluated using similar evaluation methods as described for the primary outcome. In addition to modeling change in BMI, we will also fit similar models to specified secondary outcomes which include blood pressure, WHR, and fruit and vegetable consumption.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of communities

Churches (n = 28) that agreed to participate were from fifteen counties and one independent city (hereafter treated as a county) located within Appalachian regions of the five states. According to the FY2012 ARC County Economic Status and Distressed Areas in Appalachia reports for each state [25], ten participating churches were located in ARC-designated economically distressed counties, four were found in an at-risk county, and fourteen were in transitional counties. County population sizes ranged from 13,435 to 96,189 in 2010. Per capita market income for the counties ranged from $14,598 to $29,507 in 2008, and three-year average unemployment rates for the counties ranged from 3.4% to 10.1% in 2007–2009 [25].

3.2. Characteristics of churches

Over 1400 churches exist in the counties selected to participate, but in keeping with CBPR principles, the research team elected to only contact churches recommended by community advisors that had at least 80 active members. A total of 60 churches were eligible and invited to participate and 28 (47%) agreed to participate. Of the 32 churches that declined to participate upon contact, most cited lack of interest, being too busy, and recent or upcoming changes in church leadership as reasons not to participate. All churches participating in the study were Christian. Denominations included Roman Catholic, Protestant (e.g. Methodist, Pentecostal, and Baptist) and non-denominational Christian churches. Congregation sizes ranged from 100 to more than 1000, with regular attendance reported to range from 50 to 750 church members. Some churches held only one Sunday service, and others held multiple services throughout the week as well as on Sunday. While most of the churches had only one church leader, three churches had two or more leaders. All churches had kitchens and meeting rooms or classrooms available for church events, and six churches had gymnasiums. Three of the participating churches had pre-existing health councils. Nine churches recruited more than one volunteer church navigator for the study, and the remaining churches elected one navigator. Average travel time from a regional ACCN office in each respective state to a participating church was 91.2 min for WbF (standard deviation (SD): 42.5 min) and 120.2 min for RoF (SD: 83.5 min).

3.3. Participant screening and recruitment

A total of 866 individuals were screened for eligibility: 159 (18%) were ineligible, 44 (6%) of those eligible refused to participate, and 663 enrolled into the study. Most common reasons for ineligibility included: BMI < 25 (n = 84), incomplete baseline requirements (n = 44), not medically cleared by a physician (n = 9), pregnant, breastfeeding, <9 months post-partum or planned to become pregnant (n = 8), or dietary restrictions for weight loss (n = 8). Most common reasons for refusal among those eligible included: lack of time (n = 16), lack of interest (n = 6), too tired or sick (n = 4), or did not provide a reason (n = 13). Wave 1 recruitment lasted 304 days, and 365 individuals were screened for eligibility during that period of time. The Wave 2 recruitment phase was conducted over 359 days, and 501 individuals were screened for eligibility. Enrollment was similar between waves (Wave 1 = 304 enrolled; Wave 2 = 359 enrolled).

Among the 663 enrolled in the study, 426 (64.3%) participants were in WbF churches and 237 (35.7%) in RoF churches. The average participant recruitment period from information session to kickoff event in a church was 70.5 days (SD: 37.3 days) for WbF churches and 114 days (SD: 69.5 days) for RoF churches.

3.4. Baseline characteristics of participants

3.4.1. Sociodemographic data

Participant demographics are summarized in Table 2. The mean age was 55.7 years (SD: 12.8 years) with 70% of participants being age 50 and older. Participants were predominately female (70.7%), non-Hispanic white (97.4%), and married/living with a partner (78.7%). Some participants had completed college or graduate school (37.6%), had some college experience or an associate's degree (37.3%), or had less than or equal to a high school degree or GED (25.2%). The majority of participants reported having private health insurance (67.4%) and less than 5% were uninsured. Nearly three-quarters of participants reported annual household income between $40,000 and $69,999 (37.0%) or $70,000 or more (37.4%), while 25.6%reported annual household incomes of less than $40,000. There were more women in the WbF group (74.2%) than the RoF group (64.6%). Although the participants reside in Appalachia, several characteristics are not a reflection of the region's population. For example, participants had completed higher levels of education and had higher household income levels [25,51].

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of participants.

| Variable | Level | Total n (%) | WbF n (%) | RoF n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 55.7 (12.8) | 55.5 (12.9) | 56.1 (12.5) |

| Age category (years) | <30 | 23 (3.5) | 15 (3.5) | 8 (3.4) |

| 30–39 | 47 (7.1) | 32 (7.5) | 15 (6.3) | |

| 40–49 | 129 (19.5) | 88 (20.7) | 41 (17.3) | |

| 50–59 | 203 (30.6) | 127 (29.8) | 76 (32.1) | |

| 60–69 | 173 (26.1) | 105 (24.6) | 68 (28.7) | |

| 70+ | 88 (13.3) | 59 (13.8) | 29 (12.2) | |

| Gender | Male | 194 (29.3) | 110 (25.8) | 84 (35.4) |

| Female | 469 (70.7) | 316 (74.2) | 153 (64.6) | |

| Race: White, non-Hispanic | Yes | 646 (97.4) | 413 (96.9) | 233 (98.3) |

| No | 17 (2.6) | 13 (3.1) | 4 (1.7) | |

| Marital status | Married/living w partner | 522 (78.7) | 331 (77.7) | 191 (80.6) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 107 (16.1) | 75 (17.6) | 32 (13.5) | |

| Never been married | 34 (5.1) | 20 (4.7) | 14 (5.9) | |

| Education | ≤High school/GED | 167 (25.2) | 113 (26.5) | 54 (22.8) |

| Some college or associate degree | 247 (37.3) | 160 (37.6) | 87 (36.7) | |

| Bachelor degree or more | 249 (37.6) | 153 (35.9) | 96 (40.5) | |

| Health insurance | Uninsured | 31 (4.7) | 20 (4.7) | 11 (4.6) |

| Public | 185 (27.9) | 121 (28.4) | 64 (27.0) | |

| Private | 447 (67.4) | 285 (66.9) | 162 (68.4) | |

| Household income | <$40,000 | 137 (25.6) | 90 (25.9) | 47 (25.1) |

| $40,000 to $69,999 | 198 (37.0) | 128 (36.8) | 70 (37.4) | |

| $70,000+ | 200 (37.4) | 130 (37.4) | 70 (37.4) |

GED: General Education Diploma.

3.4.2. Biometric, physical activity and diet data

Mean height, weight, waist, hip measurements and systolic and diastolic blood pressure are listed in Table 3. Among all participants, the mean WHR was 0.9 (SD:0.1), mean BMI was 33.2 (SD: 6.3), and 64.4% of participants were categorized as obese (BMI ≥ 30). Slightly over half (56.8%) of participants had systolic or diastolic blood pressure in the normal range (systolic: <120 mm Hg; diastolic: <80 mm Hg) [52]. Only 41.5% of the participants reported exercising on a regular basis. More WbF participants were categorized as obese (67.4%) than RoF (59.1%), and more WbF participants reported no regular exercise (62.8%) compared to RoF participants (50.6%).

Table 3.

Biometrics and physical activity of participants.

| Variable | Level | Total n (%) | WbF n (%) | RoF n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height m | Mean (SD) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) |

| Weight kg | Mean (SD) | 92.2 (19.5) | 92.6 (19.9) | 91.6 (18.9) |

| Waist cm | Mean (SD) | 105.5 (14.2) | 105.8 (14.5) | 104.9 (13.4) |

| Hip cm | Mean (SD) | 117.1 (12.9) | 118.0 (13.1) | 115.7 (12.5) |

| WHR | Mean (SD) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) |

| BMI | Mean (SD) | 33.2 (6.3) | 33.5 (6.6) | 32.7 (5.8) |

| BMI category | Overweight | 236 (35.6) | 139 (32.6) | 97 (40.9) |

| Obese | 427 (64.4) | 287 (67.4) | 140 (59.1) | |

| Systolic BP | Mean (SD) | 135.9 (17.6) | 136.7 (17.7) | 134.5 (17.3) |

| Diastolic BP | Mean (SD) | 82.4 (10.5) | 83.0 (10.8) | 81.2 (9.9) |

| Systolic or diastolic hypertension | Yes | 286 (43.2) | 184 (43.3) | 102 (43.0) |

| No | 376 (56.8) | 241 (56.7) | 135 (57.0) | |

| Regular exercise | Yes | 275 (41.5) | 158 (37.2) | 117 (49.4) |

| No | 387 (58.5) | 267 (62.8) | 120 (50.6) |

WbF: Walk by Faith; RoF: Ribbons of Faith; SD: standard deviation; m: meters; kg: kilogram; cm: centimeter; WHR: waist–hip ratio; BMI: body mass index; BP: blood pressure

Daily diet information is listed in Table 4. From the computer-based food frequency questionnaire developed by Viocare, Inc., estimated daily intake of fruit and vegetables were 1.2 servings (SD: 1.1) and 1.6 servings (SD: 1.3), respectively. Self-reported mean energy (kcal) per day 2038.1 (857.3) is similar to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimated calories needed to maintain calorie balance for sedentary adults (1600–2600 kcal) [53]. Food frequency data for all reported nutrients were very similar between arms.

Table 4.

Diet information reported by participants.

| Variable | Total mean (SD) |

WbF Mean (SD) |

RoF mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily fruit consumption (5-a-day method) | 1.7 (1.5) | 1.6 (1.4) | 1.8 (1.6) |

| Daily vegetable consumption (5-a-day method) | 3.3 (2.3) | 3.3 (2.2) | 3.5 (2.4) |

| Estimated daily intake of fruit (servings) | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.3 (1.2) |

| Estimated daily intake of vegetables (servings) | 1.6 (1.3) | 1.6 (1.3) | 1.6 (1.4) |

| Estimated daily intake of whole grains (servings) | 1.7 (1.4) | 1.6 (1.4) | 1.8 (1.4) |

| Energy (kcal) | 2038.1 (857.3) | 2050.0 (879.7) | 2017.0 (817.4) |

| Total carbohydrate (g) | 251.6 (104.8) | 251.4 (108.0) | 251.9 (99.3) |

| Total fat (g) | 81.9 (42.1) | 83.2 (42.2) | 79.5 (41.8) |

| Total dietary fiber (g) | 22.5 (9.6) | 22.5 (9.8) | 22.6 (9.1) |

| Protein (g) | 82.5 (36.9) | 82.4 (37.8) | 82.7 (35.3) |

| Sodium (mg) | 3634.9 (1595) | 3684.1 (1644) | 3547.9 (1501) |

| Total sugars (g) | 119.8 (62.7) | 118.6 (62.8) | 121.9 (62.6) |

| Water (mL) | 3254.2 (1373) | 3245.2 (1379) | 3270.0 (1366) |

WbF: Walk by Faith; RoF: Ribbons of Faith; SD: standard deviation; kcal: kilocalorie, g: gram, mg: milligram; mL: milliliter

WbF participants also reported whether or not friends and family were supportive of their healthy decisions. Overall, mean scores for exercise planning, scheduling and goal setting, and social support for physical activity and eating habits were all low to moderate among WbF participants (Table 5).

Table 5.

Diet and physical activity self-efficacy and social support of Walk by Faith participants.

| Variable | WbF mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Exercise planning and scheduling score (higher scores indicate greater planning, range: 10–50) | 21.0 (7.6) |

| Exercise goal-setting score (higher indicates greater goal setting, range: 10–50) | 16.3 (8.7) |

| Social support and eating habits score — family encouragement (higher indicates greater encouragement, range: 5–25) | 11.1 (5.2) |

| Social support and eating habits score — family discouragement (higher indicates greater discouragement, range: 5–25) | 11.0 (4.7) |

| Social support and eating habits score — friend encouragement (higher indicates greater encouragement, range: 5–25) | 8.9 (4.3) |

| Social support and eating habits score — friend discouragement (higher indicates greater discouragement, range: 5–25) | 9.5 (4.1) |

| UCLA social support for physical activity score — relative/friend (higher indicates greater support, range: 10–51) | 26.2 (6.7) |

| UCLA social support for physical activity score — church (higher indicates greater support, range: 10–51) | 19.3 (5.9) |

WbF: Walk by Faith; UCLA: University of California, Los Angeles.

3.4.3. Health survey data

Participant cancer-related health history and psychosocial characteristics are summarized in Table 6. Over 60% of participants reported having at least one immediate family member diagnosed with cancer, and 16% (N = 102) reported a personal history of cancer, the most common being skin (46.1%) and breast (17.6%). Cancer screening rates among participants varied greatly by test, with percent within ACS recommended guidelines ranging from 78% (WbF) to 86% (RoF) for colorectal cancer screening and 71% (WbF) to 75% (RoF) for mammography. Almost three-quarters of participants reported smoking less than 100 cigarettes in their lifetimes (72.9%); only 2.6% of participants reported being current smokers and 2.1% reported current snuff use. Rates of tobacco use were lower than published rates for the Appalachian region (24.0%)] [54]. Loneliness and depression scores were very comparable across arms and compared to national norms [29,30].

Table 6.

Cancer-related health history and psychosocial characteristics of participants.

| Variable | Level | Total n (%) | WbF n (%) | RoF n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal history of cancer | Yes | 102 (15.8) | 60 (14.3) | 42 (18.7) |

| No | 542 (84.2) | 359 (85.7) | 183 (81.3) | |

| Cancer location | Colon | 4 (3.9) | 3 (5.0) | 1 (2.4) |

| Myeloma | 2 (2.0) | 2 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 14 (13.7) | 5 (8.3) | 9 (21.4) | |

| Prostate | 7 (6.9) | 1 (1.7) | 6 (14.3) | |

| Breast | 18 (17.6) | 13 (21.7) | 5 (11.9) | |

| Cervical | 5 (4.9) | 3 (5.0) | 2 (4.8) | |

| Skin | 47 (46.1) | 29 (48.3) | 18 (42.9) | |

| Leukemia | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Lymphoma | 4 (3.9) | 4 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Family history of cancer | Yes | 385 (60.6) | 247 (59.7) | 138 (62.4) |

| No | 250 (39.4) | 167 (40.3) | 83 (37.6) | |

| Pap test (women only) | Never | 4 (0.9) | 4 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| <1 year | 235 (50.2) | 158 (50.0) | 77 (50.7) | |

| ≥1 year | 229 (48.9) | 154 (48.7) | 75 (49.3) | |

| Mammography (women only) | Never | 11 (2.6) | 6 (2.2) | 5 (3.6) |

| <1 year | 301 (72.4) | 198 (71.2) | 103 (74.6) | |

| ≥1 year | 104 (25.0) | 74 (26.6) | 30 (21.7) | |

| CRC screening: FOBT (age 50+) | Never | 257 (55.9) | 172 (59.5) | 85 (49.7) |

| <1 year | 34 (7.4) | 22 (7.6) | 12 (7.0) | |

| ≥1 year | 169 (36.7) | 95 (32.9) | 74 (43.3) | |

| CRC screening: colonoscopy (age 50+) | Never | 89 (19.2) | 65 (22.4) | 24 (13.9) |

| <10 years | 365 (78.8) | 219 (75.5) | 146 (84.4) | |

| ≥10 years | 9 (1.9) | 6 (2.1) | 3 (1.7) | |

| CRC screening: Flexible sigmoidoscopy (age 50+) | Never | 392 (85.6) | 250 (87.7) | 142 (82.1) |

| <5 years | 7 (1.5) | 6 (2.1) | 1 (0.6) | |

| ≥5 years | 59 (12.9) | 29 (10.2) | 30 (17.3) | |

| Within guidelines for CRC screening by any test | Yes | 375 (81.0) | 227 (78.3) | 148 (85.5) |

| No | 88 (19.0) | 63 (21.7) | 25 (14.5) | |

| PSA test (men only) | Never | 19 (15.2) | 13 (20.3) | 6 (9.8) |

| <1 year | 81 (64.8) | 42 (65.6) | 39 (63.9) | |

| ≥1 year | 25 (20.0) | 9 (14.1) | 16 (26.2) | |

| Smoking history | Never | 483 (72.9) | 303 (71.1) | 180 (75.9) |

| Former | 163 (24.6) | 108 (25.4) | 55 (23.2) | |

| Current | 17 (2.6) | 15 (3.5) | 2 (0.8) | |

| Snuff history | Never | 618 (93.2) | 397 (93.2) | 221 (93.2) |

| Former | 31 (4.7) | 19 (4.5) | 12 (5.1) | |

| Current | 14 (2.1) | 10 (2.3) | 4 (1.7) | |

| Chewing tobacco history | Never | 625 (94.3) | 403 (94.6) | 222 (93.7) |

| Former | 37 (5.6) | 23 (5.4) | 14 (5.9) | |

| Current | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Health literacy score (higher indicates less literate, range: 0–12) | Mean (SD) | 1.2 (1.8) | 1.2 (1.7) | 1.2 (1.9) |

| CES-D score (higher indicates greater distress, range: 0–60) | Mean (SD) | 7.9 (7.7) | 8.4 (8.2) | 7.0 (6.6) |

| CES-D 16+ | Yes | 86 (13.0) | 60 (14.2) | 26 (11.0) |

| No | 575 (87.0) | 364 (85.8) | 211 (89.0) | |

| Loneliness score (higher indicates greater loneliness, range: 3–9) | Mean (SD) | 3.9 (1.3) | 4.0 (1.3) | 3.8 (1.2) |

| Loneliness score < 4 | Yes | 161 (24.3) | 113 (26.6) | 48 (20.3) |

| No | 501 (75.7) | 312 (73.4) | 189 (79.7) | |

| Do you consider yourself Appalachian? | Yes | 367 (57.1) | 242 (58.0) | 125 (55.3) |

| N006F | 164 (25.5) | 99 (23.7) | 65 (28.8) | |

| Don’t know | 112 (17.4) | 76 (18.2) | 36 (15.9) | |

| Appalachian identity score (higher indicates greater identification, range: 12–84) | Mean (SD) | 64.1 (10.3) | 64.6 (10.4) | 63.1 (10.1) |

| Insomnia score (higher indicates greater insomnia, range: 0–41) | Mean (SD) | 15.9 (6.6) | 16.0 (6.7) | 15.8 (6.5) |

| MSPSS score (higher indicates greater support, range: 12–84) | Mean (SD) | 73.9 (8.8) | 72.2 (9.0) | 72.8 (9.0) |

WbF: Walk by Faith; RoF: Ribbons of Faith; CRC: colorectal cancer; FOBT: fecal occult blood test; SD: standard deviation; PSA: prostate-specific antigen; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale; MSPSS: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support.

4. Discussion

Many of the cancer-related disparities that exist among residents of Appalachia may be associated with modifiable behavioral risk factors including overweight and obesity, physical inactivity, tobacco use, and inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption [7–9], and lack of cancer screening. Building on the established and strong community partnerships in the five states, ACCN investigators and community partners used CBPR principles to design and implement the Walk by Faith intervention and the RoF comparison group, which draw upon the strength of Appalachia's faith community [10–14]. The goal of this group randomized trial is to test the effectiveness of the WbF intervention on reducing BMI among overweight and obese church members participating in the study.

Recruitment was originally planned to last four to six weeks in each church or approximately six months for each wave, and the overall enrollment goal was 1,000 participants. Recruitment of church members proved more difficult (i.e. only 663 recruited) and took longer than expected (on average one year) based on initial conversations with church leaders. Early efforts to recruit participants yielded low turnouts and required more time than expected. Wave 2 researchers tried to improve attendance by increasing their presence at church services and advertising the program and screening dates in bulletins and from the pulpit whenever possible. Although congregation size and an estimation of regular church attendance were provided to investigators, it may have been more helpful to gauge the number of adults who regularly attended church services by direct observation. Additional recruitment challenges included: changes in the pastor leadership in participating churches during the study start-up period that may have played a role in the lack of overall enthusiasm for the study among church members; church navigator input and enthusiasm varied and played a significant role promoting the study information sessions; and there was a higher than expected ineligibility rate among members of the church who expressed interest in the study. These findings are similar to studies conducted among faith communities in different populations groups. For example, several issues emerged among pastors from Black churches participating in focus groups [55,56]. Pastors noted the responsibility and risks associated with leading a congregation in the context of research, the importance of research among church members' competing priorities, the lack of available time, the absence of clear communication between investigators and church leaders, and the tension between science and faith [55,56]. Similarly, several church leaders in the current study reported negative experiences in the past with research conducted by others, such as the lack of honest, frequent, and transparent communication and failure to provide study results back to the participants.

To improve the partnership with the faith organizations, ACCN members increased staff presence at church and community events thus reducing distrust of the academic partners. In addition, it was extremely difficult to recruit church members in RoF churches because they were reluctant to complete baseline measurements and secure medical clearance as they did not associate those activities with cancer screening education.

To determine how representative study participants were of the residents of these Appalachian counties, we used state-level Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data (2002 and 2007) for the five-state ACCN region. The baseline characteristics among study participants were similar to BRFSS data, except the self-reported current smoking rate (2.6%) was much lower than expected, suggesting that tobacco use may be less common among Appalachian residents who attend church regularly and voluntarily participate in a health-related study than among the general Appalachian population [57] or that tobacco use is underreported due to a perceived disapproval from fellow church members and church leaders [58].

Study strengths include having established academic-community partnerships which have been used to conduct previous cancer-related education activities and research in the ACCN network, engaging community members in the development and implementation of the intervention, and using a group randomized controlled study design. However, the study is not without its limitations. Our sample size was smaller than expected due to recruitment challenges. Participants were regular churchgoers and volunteered to participate in a health-related program and, therefore, may not be representative of Appalachians as a whole.

Overweight and obesity among Appalachian residents remains a significant public health problem. Despite the challenges described, we hope that by engaging the faith community which is important to rural community members, we will be able improve the primary and secondary outcomes of participants in the Walk by Faith intevention. if successful, components from this study will be disseminated throughout the Appalachian region after our findings have been released, with the goal of improving risk factors for not only cancer, but other chronic diseases in this underserved population.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of study participants, our faith community partners and our ACCN staff, including Jordan Baeker Bispo, Marcy Bencivenga, Mary Ellen Conn, Mark Cromo, Darla Fickle, Susan Marmagas, Brent Shelton and Megan Stuart.

This research was made possible through funding from a grant (U54 CA153604) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Acknowledgements: This research was supported by grant U54 CA153604 from the National Institutes of Health and a Pelotonia Idea Grant. This study was also supported by the National Cancer Institute Grant P30 CA016058, The Behavioral Measurement Shared Resource at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Conflicts of interest: None (unless otherwise specified by co-authors).

References

- 1.Appalachian Regional Commission. Appalachia: a report by the President’s Appalachian Regional Commission. 1964. Appalachian Regional Commission, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Encyclopedia of Appalachia. The University of Tennessee Press; Knoxville, Tennessee: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackley D, Behringer B, Zheng S. Cancer mortality rates in Appalachia: descriptive epidemiology and an approach to explaining differences in outcomes. J Community Health. 2012 Aug;37(4):804–813. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9514-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Cancer Institute Cancer. Overview of Health Disparities Research: health disparities definition. 20112011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pagidipati NJ, Gaziano TA. Estimating deaths from cardiovascular disease: a review of global methodologies of mortality measurement. Circulation. 2013 Feb 12;127(6):749–756. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.128413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wingo PA, Tucker TC, Jamison PM, Martin H, McLaughlin C, Bayakly R, Bolick-Aldrich S, Colsher P, Indian R, Knight K, Neloms S, Wilson R, Richards TB. Cancer in Appalachia, 2001–2003. Cancer. 2008 Jan 1;112(1):181–192. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23132. (2007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed July 10, 2013];Diabetes Interactive Atlases. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Appalachia Community Cancer N. [Accessed 2013];The cancer burden in Appalachia. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michimi A, Wimberly MC. Spatial patterns of obesity and associated risk factors in the conterminous U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2010 Aug;39(2):e1–e12. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bencivenga M, DeRubis S, Leach P, Lotito L, Shoemaker C, Lengerich EJ. Community partnerships food pantries, and an evidence-based intervention to increase mammography among rural women. J Rural Health. 2008;24(1):91–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vanderpool R, Gainor S, Conn M, Spencer C, Allen A, Kennedy S. Adapting and implementing evidence-based cancer education interventions in rural Appalachia: real world experiences and challenges. Rural Remote Health. 2011;11(4):1807. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoenberg NE, Howell BM, Fields N. Community strategies to address cancer disparities in Appalachian Kentucky. Fam Community Health. 2012;35(1):31. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3182385d2c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz ML, Reiter P, Fickle D, Heaner S, Sim C, Lehman A, Paskett ED. Community involvement in the development and feedback about a colorectal cancer screening media campaign in Ohio Appalachia. Health Promot Pract. 2011;12(4):589–599. doi: 10.1177/1524839909353736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberto KA, Brossoie N, McPherson MC, Pulsifer MB, Brown PN. Violence against rural older women: promoting community awareness and action. Australas J Ageing. 2013;32(1):2–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2012.00649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parker EA, Robins T, Israel B, Brakefield-Caldwell W, Edgren K, Wilkins D, Eng E, Schultz A. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeHaven MJ, Hunter IB, Wilder L, Walton JW, Berry J. Health programs in faith-based organizations: are they effective? Am J Public Health. 2004;94(6):1030. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan SA, Calman NS, Golub M, Ruddock C, Billings J. The role of faith-based institutions in addressing health disparities: a case study of an initiative in the southwest Bronx. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17(2):9–19. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Ganschow P, Schiffer L, Wells A, Simon N, Dyer A. Results of a faith-based weight loss intervention for black women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(10):1393. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoenberg NE, Hatcher J, Dignan MB, Shelton B, Wright S, Dollarhide KF. Faith moves mountains: an Appalachian cervical cancer prevention program. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33(6):627. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.33.6.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Resnicow K, Jackson A, Blissett D, Wang T, McCarty F, Rahotep S, Periasamy S. Results of the healthy body healthy spirit trial. Health Psychol. 2005;24(4):339. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marmot M, Wilkinson R. Social determinants of health. Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McAlister AL, Perry CL, Parcel GS. Theory, Research, and Practice. 4. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2008. How individuals, environments, and health behaviors interact: Social Cognitive Theory, Health Behavior and Health Education; pp. 169–188. [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Cancer Society. Cancer Screening Guidelines American Cancer Society. 2014 http://www.cancer.org/healthy/findcancerearly/cancerscreeningguidelines/

- 24.Gledhill N. Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire-PAR-Q. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada; Ottawa: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Appalachian Regional Commission. County Economic Status in Appalachia. FY: [Accessed September 22 2014]. 20122011 http://www.arc.gov/research/MapsofAppalachia.asp?MAP_ID=55. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamilton CM, Strader LC, Pratt JG, Maiese D, Hendershot T, Kwok RK, Hammond JA, Huggins W, Jackman D, Pan H. The PhenX Toolkit: get the most from your measures. Am J Epidemiol. 2011 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr193. kwr193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williamson D, Womble L, Zucker N, Reas D, White M, Blouin D, Greenway F. Body image assessment for obesity (BIA-O): development of a new procedure. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(10):1326–1332. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prevention CfDCa. National Health Information Survey Tobacco Questions: 1997– Forward [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys results from two population-based studies. Res Aging. 2004;26(6):655–672. doi: 10.1177/0164027504268574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Rossi JS, Goldstein MG, Marcus BH, Rakowski W, Fiore C, Harlow LL, Redding CA, Rosenbloom D. Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviors. Health Psychol. 1994;13(1):39. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schumann A, Nigg CR, Rossi JS, Jordan PJ, Norman GJ, Garber CE, Riebe D, Benisovich SV. Construct validity of the stages of change of exercise adoption for different intensities of physical activity in four samples of differing age groups. Am J Health Promot. 2002;16(5):280–287. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-16.5.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reed GR, Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS, Marcus BH. What makes a good staging algorithm: examples from regular exercise. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12(1):57–66. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, Noorbaloochi S, Grill JP, Snyder A, Bradley KA, Nugent SM, Baines AD, VanRyn M. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):561–566. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levine DW, Kaplan RM, Kripke DF, Bowen DJ, Naughton MJ, Shumaker SA. Factor structure and measurement invariance of the Women’s Health Initiative Insomnia Rating Scale. Psychol Assess. 2003;15(2):123. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaikh AR, Yaroch AL, Nebeling L, Yeh M-C, Resnicow K. Psychosocial predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption in adults: a review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(6):535–543. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.12.028. e511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodgers WM, Wilson P, Hall C, Fraser S, Murray T. Evidence for a multidimensional self-efficacy for exercise scale. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2008;79(2):222–234. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2008.10599485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McAuley E, Blissmer B. Self-efficacy determinants and consequences of physical activity. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2000;28(2):85–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sallis JF, Grossman RM, Pinski RB, Patterson TL, Nader PR. The development of scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors. Prev Med. 1987;16(6):825–836. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Viocare. [Accessed July 30 2014];Technologies for Healthier Living. 2009 http://www.viocare.com/index.aspx.

- 43.Sjöström M, Bull F, Craig C. Towards standardized global assessment of health–related physical activity — the International Physical Activity Questionnaires (Ipaq) Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(5):S202. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Viocare. [Accessed July 30 2014];VioScreen. 2009 http://www.viocare.com/vioscreen.aspx.

- 45.Donner A, Klar N. Design and analysis of cluster randomization trials in health research. Arnold, London: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pritchard JE, Nowson CA, Wark JD. A worksite program for overweight middle-aged men achieves lesser weight loss with exercise than with dietary change. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997;97(1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(97)00015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pratt CA, Lemon SC, Fernandez ID, Goetzel R, Beresford SA, French SA, Stevens VJ, Vogt TM, Webber LS. Design characteristics of worksite environmental interventions for obesity prevention. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(9):2171–2180. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38(4):963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diggle P, Heagerty P, Liang K-Y, Zeger S. Analysis of longitudinal data. 2. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. John Wiley and Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Appalachia Community Cancer Network The Cancer Burden in Appalachia. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L, Greenlund K, Daniels S, Nichol G, Tomaselli GF, Arnett DK, Fonarow GC, Ho PM, Lauer MS, Masoudi FA, Robertson RM, Roger V, Schwamm LH, Sorlie P, Yancy CW, Rosamond WD. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association’s strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586–613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2010) Dietary guidelines for Americans. US Department of Agriculture. 7. US Government Printing Office; Washington DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Herath J, Brown C. An analysis of adult obesity and hypertension in Appalachia. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5(3) doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n3p127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ammerman A, Corbie-Smith G, George DMMSt, Washington C, Weathers B, Jackson-Christian B. Research expectations among African American church leaders in the PRAISE! project: a randomized trial guided by community-based participatory research. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1720–1727. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Corbie-Smith G, Goldmon M, Isler MR, Washington C, Ammerman A, Green M, Bunton A. Partnerships in health disparities research, the roles of pastors of black churches: potential conflict synergy, and expectations. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(9):823. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30680-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garrusi B, Nakhaee N. Religion and smoking: a review of recent literature. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2012;43(3):279–292. doi: 10.2190/PM.43.3.g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schoenberg NE, Bundy HE, Bispo JAB, Studts CR, Shelton BJ, Fields N. A rural Appalachian faith-placed smoking cessation intervention. J Relig Health. 2015;54(2):598–611. doi: 10.1007/s10943-014-9858-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]