Abstract

Background

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic skin disorder with adverse impacts on both physical and psychosocial well-being. There is presently no validated HS-specific quality-of-life (QoL) measure.

Objective

The objective of this study is to develop a QoL instrument for HS (HS-QoL) in accordance with recommended standards.

Methods

Patient interviews (concept elicitation) and expert input were used to develop the conceptual framework for outcomes perceived important to patients with HS. A HS-QoL-v1 measure was developed, and cognitive interviews with patients were conducted for pilot testing.

Results

Concept elicitation interviews with patients with HS (n = 21) generated 12 themes. Most frequently reported were impacts on daily activities and symptoms due to HS. These themes, along with literature review and input from clinical experts, informed development of the HS-QoL-v1. Nine cognitive interviews were conducted in a pilot test and resulted in the HS-QoL-v2 measure.

Conclusion

The HS-QoL-v2 is a preliminary QoL instrument for which further psychometric validation and establishment of clinimetric properties will be undertaken.

Keywords: hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), quality of life (QoL), patient-reported outcomes (PRO), HS-QoL, impacts, measure, development

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease manifested by deep-seated nodules and cysts typically in intertriginous sites, including axillae, breasts, groin, buttocks, and perineum. HS has been associated with significant impacts on physical and psychological well-being due to pain, embarrassment, and isolation1–4 and deemed to be amongst the most distressing of skin conditions.5 Despite this, there is paucity of progress in understanding the impact of HS—establishing it as a top research priority for this disease.6 As HS is a chronic condition and remissions difficult to achieve, improvements in quality of life (QoL) should be an important goal of treatment. A disease-specific QoL for HS is critical due to the unique nature of HS lesions and their location, which merits a measure inclusive of unique physical, social, and emotional domains.7,8 The HS priority-setting partnership data also identified uncertainties in multiple therapy areas in which randomised controlled trial data are sparse.6 Recent European guidelines recommend several medical therapies for HS, including topical antiseptics, oral tetracyclines, and oral disease modifiers, followed by anti–tumour necrosis factor a therapies for severe disease, in parallel with local or wider surgical techniques.9 Given the upsurge of interest in HS, a disease-specific QoL would facilitate future research by serving as a patient-centric measure of improvement, independent of clinician-reported outcomes such as inflammatory lesion counts.10 Accordingly, the objective of this study is to develop a QoL for HS (HS-QoL) adherent to recommended standards of development.11

Methods

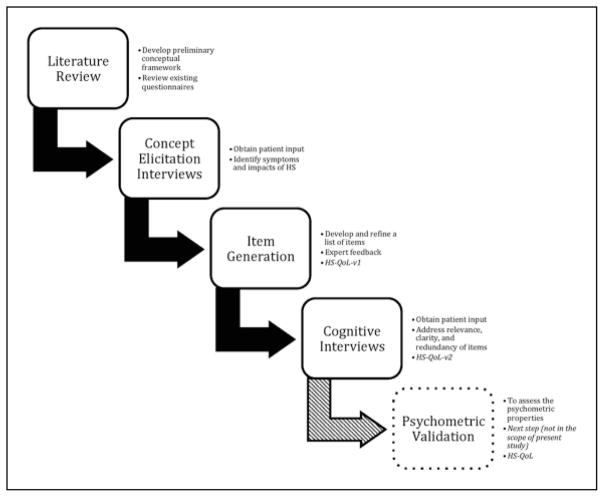

The methods used herein were in accordance with guidance from the US Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health for development of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) based on modern measurement theory.11,12 Development began with a literature review of HS outcomes, input from clinical experts, and interviews with patients with HS to explore the patient experience with HS and support for content validity. See Figure 1 for steps in developing the measure.

Figure 1.

Keys steps in the development of the hidradenitis suppurativa–quality-of-life (HS-QoL) measure.

Phase I: Concept Elicitation Interviews (HS-QoL-v1)

Participants in this phase were recruited from a search of the electronic medical record (January 1, 2012, through December 31, 2014) for a diagnosis of HS, acne inversa or International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) code 705.83. Patients 18 years or older and previously evaluated in the Department of Dermatology (Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania) were mailed an invitation to participate, which included a description of study aims and procedures. This protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Penn State College of Medicine. Patients who contacted the research team, were willing to give informed consent, had a confirmed diagnosis of HS, and were fluent in English were recruited. Patients received a $50 stipend for their participation. Patient recruitment occurred in June 2015. Interviews were performed in-person by 1 interviewer (J.S.K.) in July and August 2015. After giving verbal consent, semistructured interviews were performed using an interview guide (Table 1a), which allowed for topic consistency and flexibility. All interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. These transcripts were subsequently reviewed line by line, and words, phrases, and passages related to the impacts (restrictions, symptoms, and outcomes) of HS were coded using thematic analysis (M.S.).

Table 1.

Examples of Questions Used During (a) Concept Elicitation Interviews and (b) Cognitive Interviews.

| (a) | What bothers you the most about your HS? | Do you sometimes notice skin changes where you have HS (or had HS)? |

| Please tell me the major ways in which HS affects your life. | How much do the scars and other skin changes bother you? | |

| Does your HS get in the way of relationships with other people? | Do the marks from the HS get in the way of your activities or relationships? | |

| (b) | What was your general impression of the measure? | Can you point out any ways of measuring quality of life that we have failed to include? |

| Do you think each question is clear and easy to understand? | Are there any questions that are redundant with one another? |

HS, hidradenitis suppurativa.

Themes were selected if saturation had been reached in the concept elicitation interviews and were used to generate items for the HS-QoL-v1. Items from other QoL measures used in previous HS studies were extracted and those items deemed relevant (by 3 research associates: M.S., S.B., and L.P.) were also included in the preliminary measure. Two dermatologists (J.S.K. and J.T.) examined the measure to ensure that clinically relevant aspects of each concept were captured.

Phase 2: Pilot Test With Cognitive Interviews (HS-QoL-v2)

Participants in this phase were identified from an electronic database of medical records (March-May 2016) of a dermatology practice in Windsor, Ontario, Canada (office of J.T.). Patients who had a diagnosis of HS and indicated interest in participating were contacted by phone and asked to participate in a 30-minute interview. Patients received a $30 stipend for participation. This protocol was approved by the Applied Social Psychology Training Research Ethics Committee at the University of Windsor.

Upon agreeing to participate, an interview was scheduled and all participants were emailed a letter of information, the preliminary measure, and questions to be asked during the interview. Participants were asked to be prepared to discuss their views on whether the questions/ answers accurately and appropriately reflected their experience with HS. After reviewing and signing the consent form, the interviews commenced. The interviewer (C.M.) followed a structured guide to ensure that all participants received the same questions (Table 1b). All the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis and the measure was refined to produce the HS-QoL-v2.

Results

Phase 1: Concept Elicitation Interviews

A total of 21 patients participated (16 females [76.2%], 5 males [23.8%]; mean [SD] age, 46.8 [13.7] years [range, 23–74 years]) with various ethnicities (13 non-Hispanic white [61.9%], 3 Hispanic [14.3%], 2 black [9.5%], 1 Asian [4.8%], and 2 with mixed ethnicity [9.5%]), a mean (SD) disease duration of 20.5 (12.7) years, and Hurley stage II (12 [57%]) and stage III (9 [43%]) disease.

Patients described 12 major themes/concepts (see Table 2): (1) impacts on daily activities, (2) symptoms due to HS, (3) emotional consequences, (4) psychosocial consequences, (5) restricted clothing choices, (6) coping, (7) sexual functioning, (8) work/economic consequences, (9) interactions with medical personnel, (10) social support, (11) symptoms due to treatment, and (12) concentration issues at work and/or leisure activities. Concepts from the literature review and concept elicitation interviews were used to generate measure items (HS-QoL-v1).

Table 2.

Summary of Major Themes Generated From Concept Elicitation Interviews.

| Concept | Examples | No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Daily activities | Walking, sitting | 21 (100) |

| Symptoms due to HS | Fatigue, pain | 21 (100) |

| Emotional consequences | Depression, anger | 20 (95.2) |

| Psychosocial consequences | Isolation from others | 20 (95.2) |

| Restricted clothing choices | Clothing choices to avoid flare-ups | 19 (90.5)) |

| Coping | Social coping | 18 (85.7) |

| Sexual functioning | Embarrassment, pain during sex | 17 (81.0) |

| Work/economic consequences | Financial burden of HS management and treatment | 14 (66.7) |

| Interactions with medical personnel | Inaccessibility to medical professionals | 12 (57.1) |

| Social support | Support from family | 10 (47.6) |

| Symptoms due to treatment | Treatment side effects | 5 (23.8) |

| Concentration issues | Trouble concentrating at work | 4 (19.0) |

HS, hidradenitis suppurativa.

Phase 2: Pilot Test With Cognitive Interviews

A total of 9 patients participated (7 females [77.8%], 2 males [22.2%]; mean [SD] age, 43.44 [8.04] years [range, 30–55 years]) and were predominantly white (8 white [88.8%], 1 First Nations [11.1%]).

Participants indicated that the HS-QoL-v1 was thorough, brought awareness to a condition that is understudied, and asked about relevant issues and symptoms. Five main concerns/themes arose from the cognitive interviews (see Table 3): (1) lack of knowledge of health professionals to diagnose HS, (2) concern regarding the reference point (time frame) for questions, (3) 1 unclear item, (4) 3 items considered irrelevant, and (5) 2 themes identified as missing. In addition, most participants (n = 7 [77.8%]) indicated that they considered both scars and active lesions while reviewing the questionnaire. Response saturation was achieved with 9 participants.

Table 3.

Summary of Participant Concerns and Themes Generated From Cognitive Interviews.

| Concern/Theme | Description | No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of knowledge | Difficulties encountered while trying to receive a diagnosis for their skin condition | 5 (55.6) |

| Reference time frame | 30-day reference time frame may be too short | 3 (33.3) |

| Unclear items | Item regarding ‘drainage’ is not clear | 1 (11.1) |

| Irrelevant items | Flu-like symptoms | 3 (33.3) |

| Support from strangers | 2 (22.2) | |

| Unwanted sexual activity | 1 (11.1) | |

| Missing from preliminary measure | Emotional support throughout diagnosis | 2 (22.2) |

| Concern about medication and side effects | 1 (11.1) |

The HS-QoL-v1 was modified based on these findings: 4 items were removed, 1 altered to improve clarity, and 2 added to reflect patient concerns about difficulties encountered while seeking diagnosis. Text was also modified to differentiate active inflammatory lesions of HS from secondary lesions such as scars and tracts. The resulting HS-QoL-v2 consisted of 53 items. Participants responded to items using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = not at all and 5 = extremely. In the latter sections of the scale, participants respond using 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = never and 5 = all the time. Higher scores indicate a greater degree of impact on quality of life.

Discussion

This study is largely consistent with findings of other qualitative and quantitative studies on HS, which showed adverse impacts on emotions, intimate relations, stigmatisation, precautions, and occupation.7,13 Previous studies on HS have not comprehensively addressed the impact of this condition, including the physical, social, and psychological domains.7,10 HS has previously been neglected in medical research, and there is current uncertainty regarding optimal management. While this study found similar adverse effects of HS on QoL as in other studies, new dimensions were discovered. Concrete themes of coping and positive impacts of social support added dimensions of potential strengths. Researchers often examine individuals’ deficits (eg, negative impacts on their lives) rather than, or in combination with, the strengths individuals have or acquire as part of living with their condition. The measure developed in this study addresses QoL in a comprehensive manner, including both negative and positive aspects.

Existing studies in HS have used 3 categories of QoL measures: skin specific, general health, and psychosocial well-being.7,14–17 General QoL measures (unrelated to skin or HS) have some value as they allow for the impacts of conditions to be similarly compared.2 However, people with HS have a multifaceted experience that cannot be accurately measured by a questionnaire that only enquires about general health-related QoL. Only 1 study of fistulizing HS included a modified measure with HS-specific QoL items,18 although that measure has not been validated.

The HS-QoL-v2 developed in this study is a 53-item questionnaire suitable for use in patients with HS. Based on literature review, concept elicitation interviews, item generation, and cognitive interviews, the HS-QoL-v2 has demonstrated content validity. This version is currently undergoing psychometric validation and will subsequently require clini-metric evaluation for reliability, discriminant capacity, and responsiveness.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by Mitacs Accelerate (grant number IT06813) in partnership with the University of Windsor and Windsor Clinical Research Inc.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

- Institutional Review Board, Penn State College of Medicine

-

Applied Social Psychology Training Research Ethics Committee, University of WindsorAll procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Jemec GB, Heidenheim M, Nielsen NH. Hidradenitis suppu-rativa—characteristics and consequences. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21(6):419–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1996.tb00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matusiak L, Bieniek A, Szepietowski J. Psychophysical aspects of hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derma Venereol. 2010;90(3):264–268. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Onderdijk AJ, van der Zee HH, Esmann S, et al. Depression in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;27(4):473–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shlyankevich J, Chen AJ, Kim GE, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa is a systemic disease with substantial comorbidity burden: a chart-verified case-control analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;71(6):1144–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolkenstein P, Loundou A, Barrau K, Auquier P, Revuz J. Quality of life impairment in hidradenitis suppurativa: a study of 61 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(4):621–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ingram JR, Abbott R, Ghazavi M, et al. The hidradenitis suppurativa priority setting partnership. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(6):1422–1427. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gooderham M, Papp K. The psychosocial impact of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 suppl 1):S19–S22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alavi A. Hidradenitis suppurativa: demystifying a chronic and debilitating disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 suppl 1):S1–S2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ingram JR. Hidradenitis suppurativa: an update. Clin Med (Lond) 2016;16(1):70–73. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.16-1-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerard AJ, Feldman SR, Strowd L. Quality of life of patients with pyoderma gangrenosum and hidradenitis suppurativa. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19(4):391–396. doi: 10.1177/1203475415575013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Guidance for Industry Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Rockville, MD: FDA; 2009. pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 12.PROMIS. Instrument Development and Validation. [Accessed March 15, 2016];Scientific Standards. Version 2.0. 2012 :1–72. www.nihpromis.org.

- 13.Esmann S, Jemec G. Psychosocial impact of hidradenitis suppurativa: a qualitative study. Acta Derma Venereol. 2011;91(3):328–332. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), I: conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.EuroQol Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Quinn LM, Mostow EN, Zyzanski SJ. Skindex, a quality-of-life measure for patients with skin disease: reliability, validity, and responsiveness. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107(5):707–713. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12365600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elkjaer M, Dinesen L, Benazzato L, Rodriguez J, Logager V, Munkholm P. Efficacy of infliximab treatment in patients with severe fistulizing hidradenitis suppurativa. J Crohns Colitis. 2008;2(3):241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]