Abstract

Clinical evidence suggests superior antidepressant response over time with a repeated, intermittent ketamine treatment regimen as compared to a single infusion. However, the club drug ketamine is commonly abused. Therefore, the abuse potential of repeated ketamine injections at low doses needs to be investigated. In this study, we investigated the abuse potential of repeated exposure to either 0, 2.5, or 5 mg/kg ketamine administered once weekly for seven weeks. Locomotor activity and conditioned place preference (CPP) were assayed to evaluate behavioral sensitization to the locomotor activating effects of ketamine and its rewarding properties, respectively. Our results show that while neither males nor females developed CPP, males treated with 5 mg/kg and females treated with either 2.5 or 5 mg/kg ketamine behaviorally sensitized. Furthermore, dendritic spine density was increased in the NAc of both males and females administered 5 mg/kg ketamine, an effect specific to the NAc shell (NAcSh) in males but to both the NAc core (NAcC) and NAcSh in females. Additionally, males administered 5 mg/kg ketamine displayed increased protein expression of ΔfosB, calcium calmodulin kinase II alpha (CaMKIIα), and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), an effect not observed in females administered either dose of ketamine. However, males and females administered 5 mg/kg ketamine displayed increased protein expression of AMPA receptors (GluA1). Taken together, low-dose ketamine, when administered intermittently, induces behavioral sensitization at a lower dose in females than males, accompanied by an increase in spine density in the NAc and protein expression changes in pathways commonly implicated in addiction.

Keywords: Ketamine, sex differences, drug abuse, nucleus accumbens, sensitization, CPP, spine density, ΔfosB, CaMKIIα, BDNF, GluA1

1. Introduction

Ketamine, when administered at low doses, has fast-acting antidepressant effects in treatment-resistant patients (Zarate et al., 2006; Price et al., 2009; Murrough et al., 2013). Considering the crippling nature of depression, the increased risk for suicide, and the urgent need for fast-acting therapeutics, ketamine is seen as a promising treatment. Clinical studies have repeatedly demonstrated both fast-acting and, in some cases, long-lasting antidepressant effects, up to one week, following a single ketamine infusion in treatment-resistant patients (Larkin and Beautrais, 2011; Zarate et al., 2012). Due to its long lasting effects, ketamine infusions are administered several days apart in clinical settings, and there is evidence to suggest an enhanced antidepressant response over time with this intermittent, repeated treatment timeline compared to a single infusion (Murrough et al., 2013; Cusin et al., 2016). However, ketamine is a powerful hallucinogenic drug of abuse at higher doses, and there are serious health problems associated with its abuse (Shram et al., 2011), and while studies from our lab as well as others have examined the beneficial aspects of ketamine, little is known about potential risks for abuse with intermittent, repeated treatment regimens.

Given the higher prevalence of depression in women (Holden, 2005; Kessler et al., 2005) and given gender differences in response to classical antidepressants such as SSRIs (Young et al., 2009), further research examining antidepressant effects in both sexes is needed. In one study, gender was not a significant predictor of ketamine antidepressant efficacy in clinical populations (Niciu et al., 2014), however, only one dose of ketamine was tested (0.5 mg/kg). Our group was first to demonstrate sex differences in response to ketamine’s antidepressant effects in rats, where females are more sensitive than male rats to the antidepressant response, a finding replicated by others in mice (Carrier and Kabbaj, 2013; Franceschelli et al., 2015; Zanos et al., 2016). Because of this, and the fact that addiction and depression are often comorbid (Becker et al., 2005), one aim of this work was to investigate whether female rats would show enhanced addiction-like behaviors following repeated, low-dose ketamine treatment. It is well established that repeated exposure to drugs of abuse such as cocaine produces behavioral sensitization, a defining characteristic of addiction, where neuroadaptations induce changes in synaptic plasticity that can affect behavioral output (Robinson and Berridge, 1993; Vezina, 2004; Scofield et al., 2016). Additionally, contextual stimuli paired with rewarding drugs acquire some of the rewarding properties themselves, which can be measured using the conditioned place preference paradigm (CPP) (Napier et al., 2013). As such, the present study investigated two facets of addiction-like behaviors, examining locomotor sensitization and CPP in both male and female rats exposed to repeated, intermittent ketamine administration to mimic the aforementioned clinical treatment timeframe.

Drugs of abuse are known to trigger dramatic changes in structural plasticity in reward-related areas of the brain, such as the nucleus accumbens (NAc) (Li et al., 2004; Russo et al., 2010; Robison et al., 2013). This plasticity is thought to be mediated through converging glutamatergic signaling from the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and dopaminergic signaling from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) on the NAc (Pierce et al., 1996; Robinson and Kolb, 1997; Carlezon and Nestler, 2002). The nucleus accumbens core (NAcC) and shell (NAcSh) subregions receive specific input from PFC prelimbic and infralimbic subregions, respectively, and are involved in different aspects of addiction (Scofield et al., 2016). For instance, the NAcC is involved in evaluation of reward as well as reward learning and drug-seeking behavior, whereas the NAcSh processes motivationally relevant information from basal ganglia systems and is involved in drug-primed and context-induced reinstatement in a self-administration paradigm (Scofield et al., 2016). It has been previously shown that cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization induces structural plasticity in male rodents that can be observed through increases in dendritic spine density in the NAc, as well as increases in the transcription factor, ΔfosB, and calcium-calmodulin kinase II alpha (CaMKIIα) specific to the NAcSh (Robison et al., 2013). Indeed, CaMKIIα activity is required for ΔfosB-mediated structural and behavioral plasticity such that blocking CaMKIIα activity in the NAc prevented spine density increases and locomotor sensitization (Robison et al., 2013). Additionally, other signaling molecules such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and AMPA receptor (GluA1) are reportedly increased in the NAc following chronic cocaine exposure (Pierce et al., 1996; Li and Wolf, 2015). Accordingly, in the present study we examined whether or not there are morphological and molecular changes in the NAc following intermittent ketamine exposure in male and female rats, which may be indicative of addictive potential.

2. Methods

2.1 Animals

Fifty adult male (250–300g) and twenty four adult female (175–200g) Sprague Dawley rats were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Raleigh, NC). Animals were pair-housed in 43 × 21.5 × 25.5 cm Plexiglass cages, and maintained on a 12-hr light/dark cycle (7am–7pm). Food and water were provided ad libitum. Behavioral testing occurred during the light phase of the light/dark cycle (7a–7p); locomotor testing began at 8:00 am, while CPP began at 2:00 pm. All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the Florida State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2 Drugs

Drugs used in this study were ketamine-hydrochloride (racemic, 100 mg/mL, Henry Schein, 045822) cocaine hydrochloride (donated by National Institute on Drug Abuse), and sodium pentobarbital (Sleepaway, Patterson Vet). Drugs were dissolved into 0.9% sterile saline for dosing. Ketamine was administered at either 2.5 or 5 mg/kg, while cocaine was administered at 15 mg/kg. Sodium pentobarbital was administered at 50 mg/kg immediately prior to cardiac perfusion. All injections were administered intraperitoneally (i.p.).

2.3 Estrous Cycle Determination

Vaginal cytology was examined via vaginal lavage on a daily basis during the first 3-hr of the light cycle in order to track female rats’ estrous cycles as previously described (Becker et al., 2005; Saland et al., 2016). All female rats were tested in diestrous 1 (D1), when both progesterone and estrogen levels are low to ensure that fluctuating hormones are not interfering with behavioral data. Animals were considered to be in D1 when there was a low abundance of cells present that consisted of mainly leukocytes but also cornified epithelial cells (McLean et al., 2012).

2.4 Behavioral Testing

2.4.1 Behavioral Apparatuses

Locomotor tests were conducted in circular chambers 71.2 cm in diameter (Med Associates), containing four photo-beam sensors placed equal distances apart that record locomotor data based upon number of beam breaks. Place preference testing and conditioning sessions occurred in a 3-part chamber (Med Associates) containing white, gray, and black compartments as previously described (Dietz et al., 2007).

2.4.2 Novelty Response

All animals underwent an initial 1-hr novelty-induced locomotor test before experimental testing. This test allows categorization of rats into high responders (HR) and low responders (LR) based on locomotor scores that were either above (HR) or below (LR) the median score (Kabbaj, 2006; Wright et al., 2015). This test is routinely used in our lab to assign experimental groups and reduce variability. Novelty seeking was not used as an independent variable in any of the analyses.

2.4.3 Ketamine-induced locomotor sensitization and Conditioned Place Preference

To test for acute locomotor activating effects of ketamine, a 3-hr test was performed to assess locomotor activity after an initial injection of ketamine (Fig. 1). All animals were initially injected with saline and placed in the locomotor chamber for 1-hr, then injected with ketamine and placed back in the chamber for 2-hr.

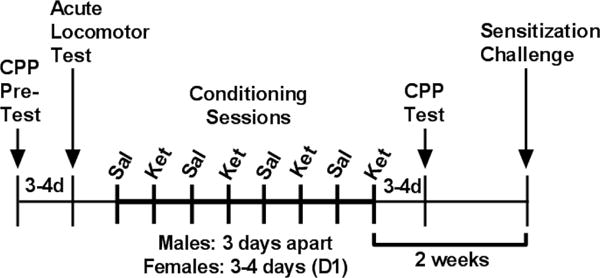

Figure 1. Timeline for intermittent ketamine treatment.

Rats received a CPP pre-test to determine side preference. Ketamine acute effects measured three to four days later, depending on stage of estrous cycle for females. Animals then underwent eight conditioning sessions (sessions 1,3,5,7 conditioned to saline; 2,4,6,8 to ketamine). Animals tested for place preference. Two weeks following last ketamine treatment, a final locomotor test was administered to measure sensitization. Animals were sacrificed at the end of the test, 30 minutes following the last ketamine injection.

CPP conditioning sessions were nested between the locomotor test measuring acute response to ketamine and the final locomotor test for behavioral sensitization. An initial 15 minute place preference pre-test was conducted prior to ketamine administration to determine baseline CPP scores as previously described (Dietz et al., 2007). The CPP paradigm utilized was biased in that animals were administered ketamine in the least-preferred chamber. Treatment groups were formed such that equal numbers of animals with an initial place preference (>150s) were divided in each group (Li, 2008).

Male rats underwent eight 45 minute conditioning sessions, each three days apart, alternating between saline and ketamine conditioning sessions. Females underwent eight 45 minute conditioning sessions, every 3–4 days while in diestrous 1 (D1), alternating between saline and ketamine conditioning sessions. A 15 min place preference test was done 3–4 days after the final conditioning session to assess whether animals had formed a place preference to the drug-paired side. CPP score was calculated by subtracting time spent in the drug-paired chamber during the post-test from time spent in the drug-paired chamber during the pre-test.

Two weeks after the last injection, all animals regardless of previous treatment group were tested for locomotor sensitization by receiving escalating doses of 0 mg/kg, 2.5 mg/kg, and 5 mg/kg ketamine every 30 min, a protocol previously used with other drugs of abuse (Waselus et al., 2013).

2.4.4 Cocaine Conditioned Place Preference

A separate group of male rats, used as a positive control for CPP, were tested for cocaine-induced CPP. The protocol was the same as males conditioned with ketamine, with conditioning sessions alternating between saline and cocaine every three days and cocaine administration occurring every six days. CPP pre- and post-tests occurred in the same timeframe as mentioned above, and CPP score was calculated the same.

2.5 Tissue Preparation and Protein Extraction

Prior to testing for the expression of behavioral sensitization, animals were randomly selected to either be rapidly decapitated for examination of NAc protein expression (n=18 males, 15 females) or transcardially perfused for examination of dendritic spine density in the NAc (n=12 males, 10 females). Animals were killed immediately after the 2 hour ketamine challenge and locomotor activity recording. Transcardial perfusion was performed on animals anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital, using 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, EMS cat# 19210) in 0.2M phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Fisher Scientific). Brains were removed afterward and stored in PFA for 24-hr, and then transferred to PBS with 1% sodium azide (Sigma, S2002) until Golgi staining. For rapid decapitation, brains were quickly removed and cryoprotected with 2-Methylbutane (VWR, cat# M1246) at −20 degrees Celsius and stored at −80 degrees Celsius until protein extraction. Frozen brains were sectioned at 200 μm in a cryostat (Leica), and tissue punches were collected bilaterally from the whole nucleus accumbens (NAc) according to Paxinos and Watson (2006). NAc proteins were then extracted using the TRI Reagent TRIZol extraction protocol according to the instructions of the manufacturer (MRC, 2014). Proteins were then diluted 1:5 in loading buffer for Western blotting.

2.6 Spine Density Quantification with Golgi Staining

Golgi staining was performed using the FD NeuroTech Rapid Golgi Stain Kit (cat# PK401), and was performed according to the protocol provided with slight modifications. The tissue used for staining was previously fixed with PFA. Neuron impregnation and staining was observed in the two week time frame the protocol suggests, and images were captured and quantified. Tissue was sliced at 150 μm on a vibratome (Leica), stained and slide mounted for further analysis.

For quantitative analysis of Golgi stained neurons, image stacks were obtained using Neurolucida Software (MBF Bioscience, Williston, Vt., USA) on a Leica DMRB microscope at 100× objective. Medium spiny neurons in the nucleus accumbens core and shell were measured using a protocol previously described (Shen et al., 2008). Briefly, dendrites were quantified >75 μm distal to the soma, after the first branch point, and no further than 200 μm distal to the soma. Dendritic segments between 40–55 μm were quantified, and at least 8 dendrites per brain area were obtained for each animal (Shen et al., 2008). Total spine density was calculated by dividing the number of spines per segment over the length of the segment. The total spine density was calculated and averaged for 8–10 dendrites in each brain area per animal, and then per treatment group (n=4/group), giving value of one number per animal. Spines were counted using ImageJ software by an observer blind to treatment conditions.

2.7 Western Blotting

Ten μg of protein underwent separation by electrophoresis in a 12% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were then transferred to 0.2 μm nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare). Prior to addition of primary antibodies, membranes were stained with Ponceau S Solution (Sigma-Aldrich), and scanned for total protein quantification, which was used as a loading control. Membranes were blocked in 5% milk in tris-buffered saline (TBS) for one hour on a rocker at room temperature, and then incubated in primary antibody overnight on a rocker at 4 degrees Celsius. The following primary antibodies were from Cell Signaling: deltaFosB (cat# 14695, 1:250), CaMKII (cat# 50049, 1:2000), pCaMKII (cat# 12716, 1:2000), GluA1 (cat#13185, 1:1000). BDNF primary antibody (cat# sc-546, 1:500) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Following overnight primary antibody incubation, membranes were washed with TBS on a rocker, and were then incubated in secondary antibody for one hour at room temperature. Secondary antibodies were obtained from Li-Cor, and included Donkey anti-Rabbit (cat# 925-32213, 1:10,000) and Goat anti-Mouse (cat# 925-32210, 1:10,000). Membranes were washed again with TBS, and scanned using the Odyssey imaging system (Li-Cor). Images were quantified using the ImageJ software, and raw values were subtracted from total protein, and then normalized to saline control animals within both males and females.

2.8 Statistical Analyses

For the acute locomotor activating effects of ketamine, two-way repeated measures ANOVA was used with 10 minute time bins as the within-groups factor and treatment (0, 2.5, or 5 mg/kg ketamine) as the between-groups factor. For the locomotor sensitization test, two-way repeated measures ANOVA was used with phase of experiment (0, 2.5, and 5 mg/kg ketamine) or 30 minute time bins as the within-groups factor and pre-treatment dose (0, 2.5, or 5 mg/kg ketamine) as the between-groups factor. For the conditioned place preference data, paired two-tailed t tests were used to compare the time spent in the drug-paired side in the post-test versus the pre-test within each treatment group. One-way ANOVA was used to analyze western blot and dendritic spine density results, with treatment group as the independent variable. Post hoc comparisons for two-way repeated measures ANOVA were made with Sidak’s post hoc when appropriate, while comparisons for one-way ANOVA were made with Fisher’s LSD when appropriate. Data are depicted as mean ± SEM, and the level of significance was set to 0.05. GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software) were used for analyses.

3. Results

3.1 Acute injection of low-dose ketamine exposure moderately alters locomotor activity in male and female rats

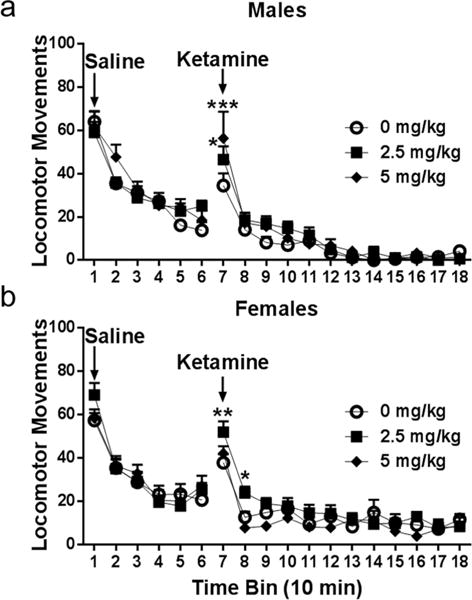

Figure 2a depicts locomotor activity in response to an acute injection of saline followed by ketamine. Upon examination of the response to saline during the first hour of the test, a significant treatment × time interaction was observed (Treatment: F(2,27)=0.35; p=0.71, Time: F(5,135)=91.90, p<0.0001; Interaction: F(10,135)=2.21, p=0.02). Post hoc analysis revealed no significant differences between treatment groups at each time point (Sidak’s post hoc, p>0.05). Over the two-hour period following ketamine administration, no main effect of treatment was observed nor was a treatment × time interaction, however there was a main effect of time (Treatment: F(2,27)=1.52, p=0.24; Time: F(11,297)=54.38, p<0.0001; Interaction: F(22,297)=1.44, p=0.09). Given the well-known rapid distribution of ketamine to the brain as well as the short half-life (Mion and Villevieille, 2013), we decided a priori to use post hoc testing to analyze early time points following ketamine administration. Sidak’s multiple comparison revealed a significant increase in locomotor movements ten minutes after ketamine administration in males receiving both 2.5 mg/kg (p=0.017) and 5 mg/kg (p<0.0001) as compared to saline controls, indicating that acute exposure to ketamine induces a locomotor activating response in males, which subsides after the first ten minutes post-injection.

Figure 2. Acute ketamine treatment induces locomotor activating effects.

(a) Males injected with saline showed no differences in locomotor movements across treatment groups. Locomotor movements were significantly increased ten minutes after receiving ketamine for males treated with both 2.5 and 5 mg/kg (p=0.017; p<0.0001, respectively). (b) Females injected with saline showed no differences in locomotor movements prior to ketamine injection. Locomotor movements were significantly increased in females treated with 2.5 mg/kg, but not 5 mg/kg, twenty minutes after receiving ketamine (10 min TB: p=0.005; 20 min TB: p=0.03). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM (males: n=10/group, females: n=8/group).

Figure 2b shows the locomotor response to acute injection of ketamine in female rats. No group differences in locomotor activity were observed in females one hour after saline injection (all p>0.05). No main effect of treatment was observed two hours following ketamine, however a significant main effect of time was observed as well as a trend towards a significant treatment × time interaction (Treatment: F(2,20)=0.0404, p=0.16; Time: F(11,220)=36.71, p<0.0001; Interaction: F(22,220)=1.51, p=0.07). Sidak’s multiple comparison revealed a significant increase in locomotor movements in females injected with 2.5 mg/kg both ten (p=0.005) and twenty (p=0.03) minutes post-treatment compared to saline controls. Interestingly, females injected with 5 mg/kg were no different from those receiving saline.

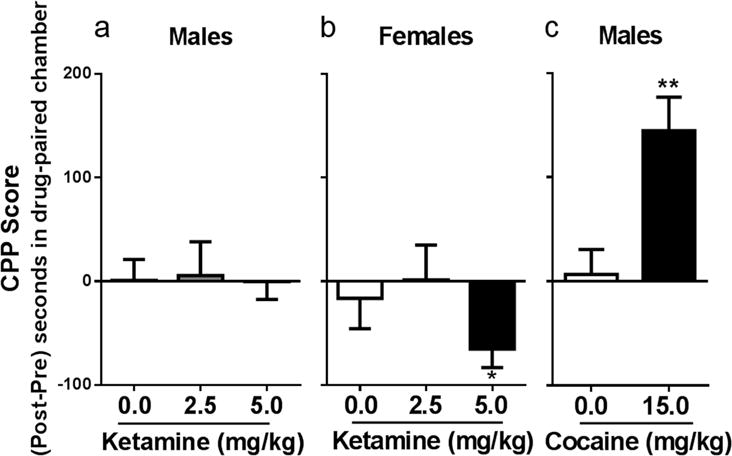

3.2 Intermittent low dose ketamine does not induce conditioned place preference in either sex

Ketamine induced place-preference was evaluated after eight intermittent conditioning sessions. Figure 3a depicts the difference in time spent in the initially least-preferred (drug-paired) side of the CPP boxes between post- and pre-tests. There were no differences in time spent in the drug-paired side in male rats conditioned every 3rd day with 0 mg/kg (t(9)=0.054, p=0.96), 2.5 mg/kg (t(8)= 0.169, p=0.87), or 5 mg/kg (t(7)=0.012, p=0.99) ketamine when comparing the difference in time spent in the drug-paired side in pre- vs post-test (Fig. 3a). Female rats were conditioned similarly to males, though sessions were every 3–4 days to account for stage of estrous cycle. As in males, no differences were observed in females conditioned with 0 mg/kg (t(7)=0.554, p=0.59) or 2.5 mg/kg (t(7)=0.042, p=0.96). Interestingly, females conditioned with 5 mg/kg ketamine spent significantly more time in the saline-paired chamber than the ketamine-paired chamber (t(5)=3.65, p=0.015), indicating a conditioned place aversion to the drug at this dose in diestrous 1 females (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. Intermittent ketamine exposure does not induce a place preference for the drug-paired side in either sex.

(a) Intermittent ketamine treatment has no effect on conditioned place preference in males. (b) Intermittent ketamine treatment to diestrous 1 females induces a conditioned place aversion at 5 mg/kg (p= 0.015). (c) Intermittent cocaine exposure (every 6 days) induces a place preference for the drug-paired side (p=0.003). All data expressed as mean ± SEM (males: n= 7–10/group; females: n=6–8/group).

3.3 Intermittent cocaine induces a conditioned place preference in male rats

As a positive control, a separate cohort of males was used to determine intermittent cocaine’s effect on conditioned place preference. Using the same schedule of drug administration as was used with ketamine, male rats in this cohort were conditioned with 0 and 15 mg/kg. Whereas no change in time spent in the drug-paired chamber occurred in males conditioned to saline (t(9)=0.698, p=0.50), males conditioned to 15 mg/kg cocaine every 3rd day spent significantly more time in the drug-paired side (t(7)=4.50, p=0.003), demonstrating the development of a place preference (Fig 3c).

3.4 Females sensitize to intermittent locomotor-activating effects of ketamine exposure at a lower dose than males

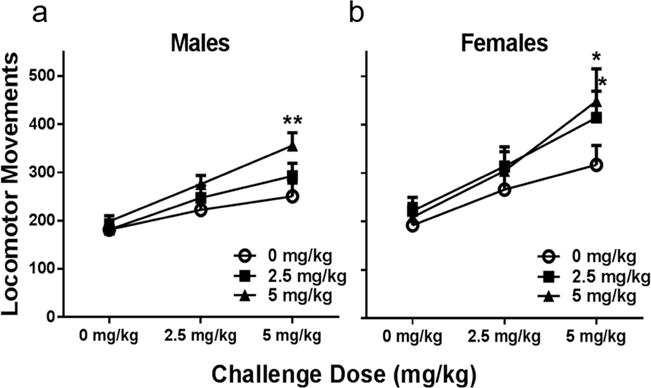

Animals underwent a two-week drug abstinence period after the last ketamine treatment during conditioned place preference testing. Male and female rats were subjected to a final locomotor test to examine the expression of behavioral sensitization. All animals were injected with escalating doses of 0, 2.5, and 5 mg/kg ketamine in 30 minute intervals, regardless of previous treatment conditions, a protocol adapted from a previous study examining cocaine sensitization (Waselus et al., 2013).

In males, there was a significant interaction between pre-treatment dose and challenge dose (Pre-treatment dose: F(2,26)=1.96, p=0.16; Challenge dose: F(2,52)=131.6, p<0.0001; Interaction: F(4,52)=7.19, p=0.0001). Post-hoc analyses revealed a significant increase in locomotor activity in males previously treated with 5 mg/kg ketamine compared to those receiving saline (Sidak’s multiple comparison, p=0.002), when challenged with a dose of 5 mg/kg ketamine (Fig. 4a). This increase suggests a heightened response to ketamine in male rats undergoing the repeated treatment regimen with 5 mg/kg ketamine as compared to those administered ketamine for the first time.

Figure 4. Females sensitize to intermittent ketamine treatment at a lower dose than males.

(a) Intermittent ketamine treatment with 5 mg/kg, but not 2.5 induces behavioral sensitization. When receiving escalating doses of ketamine in thirty minute increments, locomotor movements were significantly increased in males previously treated with 5 mg/kg ketamine (p=0.002). (b) In females, ketamine induces behavioral sensitization at both 2.5 and 5 mg/kg. Locomotor movements thirty minutes after receiving a challenge dose of 5 mg/kg were significantly higher in females treated at both doses (2.5: p= 0.03; 5: p=0.013). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM (males: n=9–10/group, females: n=8/group).

Females underwent the same locomotor challenge test two weeks after the last ketamine treatment to test for the expression of behavioral sensitization. There was a significant interaction between pre-treatment dose and challenge dose (Pre-treatment dose: F(2,20)=1.77, p=0.19; Challenge dose: F(2,40)=87.5, p<0.0001; Interaction: F(4,40)=3.59, p=0.014). Figure 4b shows locomotor movements of female rats previously treated with 0, 2.5, or 5 mg/kg ketamine. When challenged with 5 mg/kg ketamine, females previously exposed to repeated treatments with both 2.5 and 5 mg/kg ketamine displayed a significant increase in locomotor movements compared to those previously treated with saline (Sidak’s multiple comparison, p= 0.029 and p=0.013, respectively). Interestingly, females sensitized to both 2.5 and 5 mg/kg, whereas males only sensitized to 5 mg/kg, which could reflect greater sensitivity of females to the drug than males, a result supported by previous reports from our lab (Carrier and Kabbaj, 2013; Saland et al., 2016).

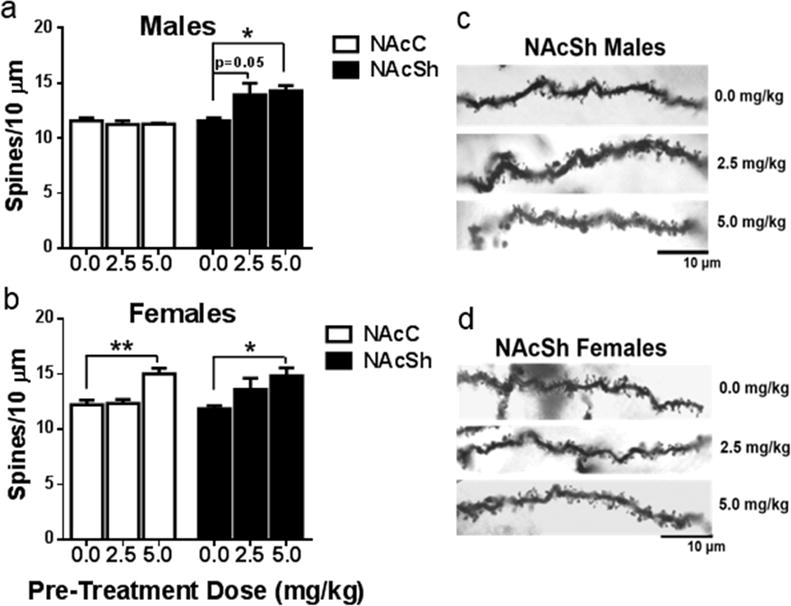

3.5 Increased spine density in the NAc in animals chronically treated with ketamine

Dendritic spine density was quantified on distal dendrites of medium spiny neurons in both the nucleus accumbens core (NAcC) and shell (NAcSh). There was a main effect of treatment on spine density in the NAc shell (F(2,9)=4.72, p=0.04), but not the core (F(2,9)=0.54, p=0.6) of males. Post hoc analysis revealed a significant increase in spine density in male rats chronically treated with 5 mg/kg as compared to saline (Fisher’s LSD, p=0.02). Further, there was a trend towards significance in males treated with 2.5 mg/kg ketamine when compared to saline animals (Fisher’s LSD, p=0.05). Taken together, these results show that males who sensitized to ketamine show an increase in spine density in the nucleus accumbens shell but not core (Fig. 5 a,c).

Figure 5. Nucleus Accumbens spine density increased following intermittent ketamine exposure.

(a) Males treated with ketamine show no change in dendritic spine density in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) core. Males treated with 2.5 showed a trend toward a significant increase in spine density (p=0.05) and males treated with 5 mg/kg ketamine showed a significant increase in spine density in the NAc shell (p=0.02). (b) Females treated with 5 mg/kg ketamine show a significant increase in dendritic spine density in both the NAc core (p=0.003) and shell (p=0.01). (c,d) Representative images depicting spine density in the NAc shell for both males and females at each dose. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=8–10 dendrites/NAc subregion/animal, 3–4 animals/treatment group).

In the NAcC of females, there was a significant main effect of treatment (F(2,7)=12.39, p=0.005), where females chronically treated with 5 mg/kg ketamine exhibited a significant increase in spine density relative to those treated with saline (Fisher’s LSD, p= 0.003). Similarly, there was a main effect of treatment in the NAcSh of females (F(2,8)= 5.171, p=0.04) that revealed a significant increase in spine density only in females chronically treated with 5 mg/kg as compared to those treated with saline (Fisher’s LSD, p=0.01). Interestingly, no difference in density was apparent in females treated with 2.5 mg/kg ketamine (Fig. 5 b,d).

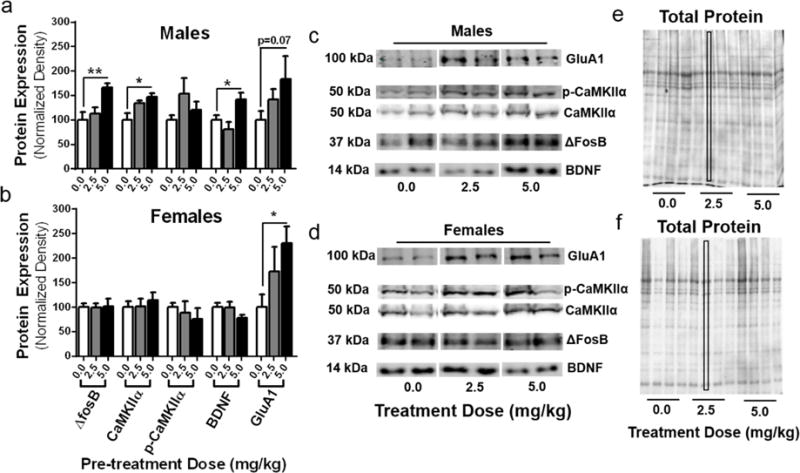

3.6 Increased expression of proteins associated with sensitization in males but not females

In males, there was a main effect of treatment on ΔfosB (F(2,9)=7.46, p=0.012), CaMKIIα (F(2,8)=5.63, p=0.03), and BDNF (F(2,9)=6.06, p=0.02) expression. Fisher’s LSD showed significantly greater expression of these proteins in males treated with 5 mg/kg compared to saline controls (ΔFosB, p=0.005; CaMKIIα, p=0.01; BDNF, p=0.04) (Fig. 6a). There was no effect of treatment on levels of p-CaMKIIα (F(2,9)=1.47,p=0.28) or GluA1 (F(2,10)=2.04, p=0.18). Given reports demonstrating ketamine’s time-dependent increases on GluA1 expression in both male and female rats in the hippocampus (Zhang et al., 2017), we decided a priori to use post hoc analysis to examine ketamine effects on GluA1 expression in males. Fisher’s LSD showed a strong trend towards an increase in GluA1 expression in males treated with 5 mg/kg (p=0.07)

Figure 6. Nucleus Accumbens protein expression changes in males and females.

(a) Males treated with 5 mg/kg ketamine showed a significant increase in protein expression of ΔfosB (p=0.01), CaMKIIα (p=0.03), and BDNF (p=0.02) as well as a trend towards an increase in GluA1 expression (p=0.07). (b) In females, ketamine had no effect on NAc protein expression of targets that were affected in males, however there was a significant increase in GluA1 expression (p=0.01). (c,d) Representative blots for males and females depicting expression of GluA1, p-CaMKIIα, CaMKIIα, ΔfosB, and BDNF for each treatment dose. (e,f) Protein expression was normalized to total protein stains using Ponceau S staining solution for males (e) and females (f). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=4/group males and females).

In females, treatment had no effect on expression of ΔfosB (F(2,9)=0.007,p=0.99), CaMKIIα (F(2,9)=0.27, p=0.77), p-CaMKIIα (F(2,9)=0.41, p=0.67), or BDNF (F(2,9)= 1.59, p=0.255). However, there was a main effect of treatment on expression levels of GluA1 (F(2,10)=5.26, p=0.03), which was significantly increased in females previously treated with 5 mg/kg (Fig. 6b) compared to saline controls (Fisher’s LSD, p= 0.01).

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that intermittent, repeated low-dose ketamine administration produces behavioral sensitization in both male and female rats. Further, we show that the induction of behavioral sensitization occurs at a lower dose in female rats as compared to males. Additionally, ketamine administration led to an increase in dendritic spine density in males that was specific to the NAcSh, whereas females displayed increases in both the NAcC and NAcSh. Finally, intermittent ketamine induced an increase in NAc protein expression of common markers of addiction such as ΔfosB, CaMKIIα, and BDNF in males but not females, though both sexes displayed increases in GluA1 expression.

CPP is a model of Pavlovian conditioning where strong associations between contextual stimuli and addictive drugs are formed, and are strong enough that over time the stimuli begin to produce similar motivational effects on their own (Napier et al., 2013). Over time, these acquired drug-related stimuli are thought of as cues that may promote relapse (Ludwig et al., 1986; Robinson and Berridge 1993). Studies demonstrate the formation of a place preference across a wide range of addictive drugs such as cocaine, ethanol, nicotine, morphine, and heroin (Tzschentke, 2007). Previous studies demonstrated ketamine’s ability to elicit a place preference in male rats when administered at doses of either 5 or 10 mg/kg every other day (Li et al., 2008; Botanas et al., 2015). The present study was the first to use a CPP paradigm with conditioning sessions days apart from each other in order to mimic clinical timeframes of ketamine administration. In the present study, male rats did not form a place preference neither for 2.5 mg/kg nor 5 mg/kg ketamine. However, male rats administered cocaine every six days reliably formed a place preference, indicating that intermittent conditioning sessions in this regimen do not interfere with contextual learning. Additionally, female rats did not form a place preference to 2.5 mg/kg ketamine and displayed an aversion to 5 mg/kg ketamine. Altogether, these results suggest the positive motivational effects of low-dose ketamine may be time-dependent, since CPP formation observed at doses in previous studies with a more compact timeline dissipates when administered once weekly. Furthermore, we validate this CPP protocol by demonstrating cocaine’s ability to elicit a place preference in male rats when administered in an intermittent fashion.

Drug-induced behavioral sensitization is defined as an enhanced behavioral or physiological response following repeated drug exposure compared to the first drug presentation (Robinson and Berridge, 1993; Scofield et al., 2016). In animals, drugs of abuse produce this effect through sensitization of locomotor activity, and thus it can be measured by quantifying locomotor activity after repeated drug-delivery (Scofield 2016, Robinson Berridge, 1993). Additionally, drug-induced sensitization is indicative of mesocorticolimbic dopamine reward system reorganization that can underlie the induction of structural plasticity (Steketee and Kalivas, 2011). In male rats, ketamine-induced locomotor sensitization has been observed in doses as low as 5 mg/kg and as high as 50 mg/kg (Popik et al., 2008; Botanas et al., 2015). Additionally, one study reported locomotor sensitization at a dose of 10 mg/kg in female rats (Wiley et al., 2011). The present study demonstrates that repeated, intermittent ketamine administration at a dose of 5 mg/kg, but not 2.5 mg/kg, produces behavioral sensitization in male rats. Furthermore, both 2.5 and 5 mg/kg ketamine, when administered intermittently to females in diestrous 1 induces sensitization, indicating that females display an enhanced sensitivity to the sensitizing effects of ketamine as compared to males. These findings parallel previous studies using cocaine, and demonstrating that female rodents will display behavioral sensitization at both lower doses and in shorter timeframes than males (Festa and Quinones-Jenab, 2004; Carroll and Anker, 2010).

CPP and locomotor sensitization are two indices of drug abuse potential, and though addictive drugs often times produce both a place preference and sensitization collectively, the induction of one does not ensure that the other will also occur. As such, the present study indicates a disparity between drug-paired contextual learning and locomotor sensitization to ketamine. Males exposed to 5 mg/kg ketamine and females exposed to 2.5 mg/kg ketamine displayed no difference in CPP score over time, but sensitized to ketamine. Additionally, females treated with 5 mg/kg ketamine displayed an aversion at this dose, while also developing sensitization. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated with other drugs such as ethanol that conditioned place aversion (CPA) occurs in naïve-drinking male rats, despite the well-established induction of ethanol sensitization (Rustay et al., 2001; Tzschentke, 2007; Camarini and Pautassi, 2016). Also, the presence of both estradiol and progesterone have been shown to enhance cocaine CPP in ovariectomized (OVX) female rats (Segarra et al., 2010). It is therefore possible that the natural nadir of ovarian hormones in diestrous 1 females utilized in this study contributed to the aversion seen in female rats when ketamine is administered at 5 mg/kg.

Once ketamine-induced sensitization was established in both males and females, dendritic spine density was examined in the NAcC and NAcSh. In males, ketamine did not affect NAcC spine density. However, 5 mg/kg ketamine induced an increase in NAcSh spine density and 2.5 mg/kg ketamine elicited a strong trend towards an increase. In females, 5 mg/kg ketamine induced an increase in both NAcC and NAcSh spine density, while 2.5 mg/kg ketamine produced no change in either subregion. Our lab and others have demonstrated ketamine’s effects on spine density in the prefrontal cortex (Duman et al., 2012; Sarkar and Kabbaj, 2016) and others have reported similar effects in the hippocampus (Duman et al., 2012), but the present study is the first to report ketamine effects on NAc plasticity. It is well established that behavioral sensitization leads to mesocorticolimbic reorganization and structural plasticity across a wide range of drugs of abuse such as cocaine, amphetamine, ethanol, and nicotine and can affect NAc spine density (Robinson and Kolb, 1997; Nestler et al., 2004; Kalivas et al., 2009). Thus, it is not surprising that both males and females treated with 5 mg/kg ketamine developed behavioral sensitization as well as an increase in NAc dendritic spine density. Interestingly, males treated with ketamine at 2.5 mg/kg did not sensitize but exhibited a strong trend toward an increase in NAcSh spine density. It is possible that this increased spine density is associated with hedonic reward and not motivational reward, however further studies are needed to explore this possibility. It is indeed important to note that the Golgi method does not allow differentiation between the different spine subtypes (thin, stubby, or mushroom) nor differentiation between spines located on the two subtypes of medium spiny neurons (dopamine D1-R and D2-R containing neurons), both necessary aspects to examine in the future to better understand ketamine’s role in structural plasticity in the NAc.

Within each individual dendritic spine head lies the postsynaptic density (PSD), which houses a matrix of receptors such as NMDA and AMPA, as well as supporting proteins such as CaMKII (Yamauchi, 2002; Spiga et al., 2014). Upstream signaling molecules such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) can influence downstream signaling targets such as ΔfosB, a transcription factor heavily associated with addiction (Wiley et al., 2011; Li and Wolf, 2015). Thus, the present study sought to examine whether protein expression of the aforementioned targets could be affected by low-dose ketamine as they are affected by other drugs of abuse like cocaine. Males treated with 5 mg/kg ketamine displayed significant increases in NAc protein expression of ΔfosB and CaMKIIα. This is consistent with a previous study demonstrating their roles in sensitization, where blockade of CaMKIIα in the NAc disrupts ΔfosB transcription, blocks cocaine-induced sensitization, and prevents spine density increase (Robison et al., 2013). However, in our study, this effect was not observed in females treated with either dose of ketamine, indicating that the role these signaling molecules may play in ketamine sensitization may be exclusive to males. Additionally, male rats exposed to cocaine display an increase in BDNF expression in both the NAcC and NAcSh (Li and Wolf, 2015). Our study reports similar changes in BDNF protein expression in male rats, where males that sensitized to 5 mg/kg ketamine displayed an increase in BDNF expression compared to controls. Interestingly, this effect was not observed in females treated with either dose. However, both males and females administered 5 mg/kg ketamine displayed increased GluA1 expression, which could serve as a common protein target involved in ketamine sensitization between sexes.

While it is compelling to observe protein expression increases in ketamine-sensitized males similar to that commonly seen with other drugs of abuse, it remains unclear why the majority of proteins examined in females remain unchanged. It is possible the observed effect is due to stage of estrous cycle as all females used in the present study were tested and administered ketamine in diestrous 1. A recent study from our lab showed cycle-dependent effects with acquisition of ketamine in a self-administration model, demonstrating that female rats in diestrous 1 do not acquire ketamine self-administration over ten sessions whereas males and proestrous females do (Wright et al., 2016). However, more studies examining cycle-dependent effects on NAc protein expression following ketamine administration are necessary to fully elucidate sex differences in protein expression following repeated ketamine injections.

While the use of repeated low-dose ketamine is on the rise as an off-label treatment for depression, more studies are needed to examine the safety of such treatments to understand the potential for abuse it might have. The present study demonstrates the induction of behavioral sensitization in males administered 5 mg/kg ketamine and females administered either 2.5 or 5 mg/kg ketamine. However, the lack of CPP formation to intermittent administration of ketamine in both males and females could be indicative of the absence of rewarding properties of ketamine at low doses with this treatment regimen. Self-administration studies examining ketamine’s motivational aspects at low doses are necessary to further our understanding of the abuse liability when administering it as an antidepressant. Accompanied by sensitization was the induction of structural plasticity, displayed through increases in NAc dendritic spine density and protein expression commonly observed with other drugs of abuse such as cocaine. Specifically, increases in ΔfosB and CaMKIIα in males and GluA1 in both sexes were observed. Taken together, this is the first evidence to date demonstrating structural and molecular neuroadaptations indicative of ketamine abuse potential. With these findings, we suggest additional examination into the addictive potential of low-dose ketamine in both sexes, particularly assessing through self-administration to elucidate motivation, craving, and relapse behaviors.

Research Highlights.

Repeated, intermittent, low-dose ketamine induces locomotor sensitization at a lower dose in female rats than males.

Ketamine sensitization was associated with increased dendritic spine density in the nucleus accumbens shell of male rats, and both the core and shell of female rats.

Male rats exposed to repeated ketamine displayed increases in nucleus accumbens protein expression of ΔfosB, CaMKIIα, BDNF, and GluA1 whereas female rats only displayed increases in GluA1 expression.

Acknowledgments

Funding source:

This research was supported by The Florida State University Department of Biomedical Sciences and National Institute of Mental Health grants to M.K. (R01 MH087583 and R01 MH099085).

We would like to thank Dr. Frank Johnson for his great assistance with data acquisition and analyses of spine density work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

C.E.S and M.K. designed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. C.E.S, K.J.S., and A.M.D conducted behavioral experiments. S.K.S. assisted in analysis of data. K.N.W. assisted with editing the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Becker JB, Arnold AP, Berkley KJ, Blaustein JD, Eckel LA, Hampson E, Herman JP, Marts S, Sadee W, Steiner M, Taylor J, Young E. Strategies and methods for research on sex differences in brain and behavior. Endocrinology. 2005;146(4):1650–1673. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botanas CJ, de la Pena JB, Dela Pena IJ, Tampus R, Yoon R, Kim HJ, Lee YS, Jang CG, Cheong JH. Methoxetamine, a ketamine derivative, produced conditioned place preference and was self-administered by rats: Evidence of its abuse potential. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2015;133:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camarini R, Pautassi RM. Behavioral sensitization to ethanol: Neural basis and factors that influence its acquisition and expression. Brain Res Bull. 2016;125:53–78. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Jr, Nestler EJ. Elevated levels of GluR1 in the midbrain: a trigger for sensitization to drugs of abuse? Trends Neurosci. 2002;25(12):610–615. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier N, Kabbaj M. Sex differences in the antidepressant-like effects of ketamine. Neuropharmacology. 2013;70:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Anker JJ. Sex differences and ovarian hormones in animal models of drug dependence. Horm Behav. 2010;58(1):44–56. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusin C, Ionescu DF, Pavone KJ, Akeju O, Cassano P, Taylor N, Eikermann M, Durham K, Swee MB, Chang T, Dording C, Soskin D, Kelley J, Mischoulon D, Brown EN, Fava M. Ketamine augmentation for outpatients with treatment-resistant depression: Preliminary evidence for two-step intravenous dose escalation. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0004867416631828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz D, Wang H, Kabbaj M. Corticosterone fails to produce conditioned place preference or conditioned place aversion in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2007;181(2):287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS, Li N, Liu RJ, Duric V, Aghajanian G. Signaling pathways underlying the rapid antidepressant actions of ketamine. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festa ED, Quinones-Jenab V. Gonadal hormones provide the biological basis for sex differences in behavioral responses to cocaine. Horm Behav. 2004;46(5):509–519. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschelli A, Sens J, Herchick S, Thelen C, Pitychoutis PM. Sex differences in the rapid and the sustained antidepressant-like effects of ketamine in stress-naive and “depressed” mice exposed to chronic mild stress. Neuroscience. 2015;290:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden C. Sex and the suffering brain. Science. 2005;308(5728):1574. doi: 10.1126/science.308.5728.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbaj M. Individual differences in vulnerability to drug abuse: the high responders/low responders model. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2006;5(5):513–520. doi: 10.2174/187152706778559318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Lalumiere RT, Knackstedt L, Shen H. Glutamate transmission in addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1):169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Walters EE, Wang P, Wells KB, Zaslavsky AM. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(24):2515–2523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin GL, Beautrais AL. A preliminary naturalistic study of low-dose ketamine for depression and suicide ideation in the emergency department. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14(8):1127–1131. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711000629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Fang Q, Liu Y, Zhao M, Li D, Wang J, Lu L. Cannabinoid CB(1) receptor antagonist rimonabant attenuates reinstatement of ketamine conditioned place preference in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;589(1–3):122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Wolf ME. Multiple faces of BDNF in cocaine addiction. Behav Brain Res. 2015;279:240–254. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Acerbo MJ, Robinson TE. The induction of behavioural sensitization is associated with cocaine-induced structural plasticity in the core (but not shell) of the nucleus accumbens. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20(6):1647–1654. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RJ, Lee FS, Li XY, Bambico F, Duman RS, Aghajanian GK. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met allele impairs basal and ketamine-stimulated synaptogenesis in prefrontal cortex. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(11):996–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig AM. Pavlov’s “bells” and alcohol craving. Addict Behav. 1986;11(2):87–91. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean AC, Valenzuela N, Fai S, Bennett SA. Performing vaginal lavage, crystal violet staining, and vaginal cytological evaluation for mouse estrous cycle staging identification. J Vis Exp. 2012;(67):e4389. doi: 10.3791/4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mion G, Villevieille T. Ketamine pharmacology: an update (pharmacodynamics and molecular aspects, recent findings) CNS Neurosci Ther. 2013;19(6):370–380. doi: 10.1111/cns.12099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrough JW, Iosifescu DV, Chang LC, Al Jurdi RK, Green CE, Perez AM, Iqbal S, Pillemer S, Foulkes A, Shah A, Charney DS, Mathew SJ. Antidepressant efficacy of ketamine in treatment-resistant major depression: a two-site randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(10):1134–1142. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13030392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrough JW, Perez AM, Pillemer S, Stern J, Parides MK, aan het Rot M, Collins KA, Mathew SJ, Charney DS, Iosifescu DV. Rapid and longer-term antidepressant effects of repeated ketamine infusions in treatment-resistant major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(4):250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napier TC, Herrold AA, de Wit H. Using conditioned place preference to identify relapse prevention medications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(9 Pt A):2081–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Molecular mechanisms of drug addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47(Suppl 1):24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niciu MJ, Luckenbaugh DA, Ionescu DF, Guevara S, Machado-Vieira R, Richards EM, Brutsche NE, Nolan NM, Zarate CA., Jr Clinical predictors of ketamine response in treatment-resistant major depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(5):e417–423. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce RC, Bell K, Duffy P, Kalivas PW. Repeated cocaine augments excitatory amino acid transmission in the nucleus accumbens only in rats having developed behavioral sensitization. J Neurosci. 1996;16(4):1550–1560. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01550.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popik P, Kos T, Sowa-Kucma M, Nowak G. Lack of persistent effects of ketamine in rodent models of depression. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;198(3):421–430. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1158-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RB, Nock MK, Charney DS, Mathew SJ. Effects of intravenous ketamine on explicit and implicit measures of suicidality in treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(5):522–526. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1993;18(3):247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Kolb B. Persistent structural modifications in nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex neurons produced by previous experience with amphetamine. J Neurosci. 1997;17(21):8491–8497. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08491.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robison AJ, Vialou V, Mazei-Robison M, Feng J, Kourrich S, Collins M, Wee S, Koob G, Turecki G, Neve R, Thomas M, Nestler EJ. Behavioral and structural responses to chronic cocaine require a feedforward loop involving DeltaFosB and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in the nucleus accumbens shell. J Neurosci. 2013;33(10):4295–4307. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5192-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo SJ, Dietz DM, Dumitriu D, Morrison JH, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. The addicted synapse: mechanisms of synaptic and structural plasticity in nucleus accumbens. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33(6):267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustay NR, Boehm SL, 2nd, Schafer GL, Browman KE, Erwin VG, Crabbe JC. Sensitivity and tolerance to ethanol-induced incoordination and hypothermia in HAFT and LAFT mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70(1):167–174. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00595-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saland SK, Schoepfer KJ, Kabbaj M. Hedonic sensitivity to low-dose ketamine is modulated by gonadal hormones in a sex-dependent manner. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21322. doi: 10.1038/srep21322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar A, Kabbaj M. Sex Differences in Effects of Ketamine on Behavior, Spine Density, and Synaptic Proteins in Socially Isolated Rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(6):448–456. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scofield MD, Heinsbroek JA, Gipson CD, Kupchik YM, Spencer S, Smith AC, Roberts-Wolfe D, Kalivas PW. The Nucleus Accumbens: Mechanisms of Addiction across Drug Classes Reflect the Importance of Glutamate Homeostasis. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68(3):816–871. doi: 10.1124/pr.116.012484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segarra AC, Agosto-Rivera JL, Febo M, Lugo-Escobar N, Menendez-Delmestre R, Puig-Ramos A, Torres-Diaz YM. Estradiol: a key biological substrate mediating the response to cocaine in female rats. Horm Behav. 2010;58(1):33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Sesack SR, Toda S, Kalivas PW. Automated quantification of dendritic spine density and spine head diameter in medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens. Brain Struct Funct. 2008;213(1–2):149–157. doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shram MJ, Sellers EM, Romach MK. Oral ketamine as a positive control in human abuse potential studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;114(2–3):185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiga S, Mulas G, Piras F, Diana M. The “addicted” spine. Front Neuroanat. 2014;8:110. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steketee JD, Kalivas PW. Drug wanting: behavioral sensitization and relapse to drug-seeking behavior. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63(2):348–365. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzschentke TM. Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm: update of the last decade. Addict Biol. 2007;12(3–4):227–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezina P. Sensitization of midbrain dopamine neuron reactivity and the self-administration of psychomotor stimulant drugs. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;27(8):827–839. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waselus M, Flagel SB, Jedynak JP, Akil H, Robinson TE, Watson SJ., Jr Long-term effects of cocaine experience on neuroplasticity in the nucleus accumbens core of addiction-prone rats. Neuroscience. 2013;248:571–584. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Evans RL, Grainger DB, Nicholson KL. Locomotor activity changes in female adolescent and adult rats during repeated treatment with a cannabinoid or club drug. Pharmacol Rep. 2011;63(5):1085–1092. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(11)70627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright KN, Hollis F, Duclot F, Dossat AM, Strong CE, Francis TC, Mercer R, Feng J, Dietz DM, Lobo MK, Nestler EJ, Kabbaj M. Methyl supplementation attenuates cocaine-seeking behaviors and cocaine-induced c-Fos activation in a DNA methylation-dependent manner. J Neurosci. 2015;35(23):8948–8958. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5227-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright KN, Strong CE, Addonizio MN, Brownstein NC, Kabbaj M. Reinforcing properties of an intermittent, low dose of ketamine in rats: effects of sex and cycle. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4470-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi T. Molecular constituents and phosphorylation-dependent regulation of the post-synaptic density. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2002;21(4):266–286. doi: 10.1002/mas.10033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young EA, Kornstein SG, Marcus SM, Harvey AT, Warden D, Wisniewski SR, Balasubramani GK, Fava M, Trivedi MH, John Rush A. Sex differences in response to citalopram: a STAR*D report. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43(5):503–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moaddel R, Morris PJ, Georgiou P, Fischell J, Elmer GI, Alkondon M, Yuan P, Pribut HJ, Singh NS, Dossou KS, Fang Y, Huang XP, Mayo CL, Wainer IW, Albuquerque EX, Thompson SM, Thomas CJ, Zarate CA, Zanos P, Jr, Gould TD. NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Nature. 2016;533(7604):481–486. doi: 10.1038/nature17998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarate CA, Jr, Brutsche NE, Ibrahim L, Franco-Chaves J, Diazgranados N, Cravchik A, Selter J, Marquardt CA, Liberty V, Luckenbaugh DA. Replication of ketamine’s antidepressant efficacy in bipolar depression: a randomized controlled add-on trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(11):939–946. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarate CA, Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, Brutsche NE, Ameli R, Luckenbaugh DA, Charney DS, Manji HK. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(8):856–864. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Yamaki VN, Wei Z, Zheng Y, Cai X. Differential regulation of GluA1 expression by ketamine and memantine. Behav Brain Res. 2017;316:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]