Abstract

Background

Volumetry of medial temporal lobe (MTL) structures to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in its earliest symptomatic stage could be of great importance for interventions or disease modifying pharmacotherapy.

Objective

This study aimed to demonstrate the first application of an automatic segmentation method of MTL subregions in a clinical population. Automatic segmentation of magnetic resonance images (MRIs) in a research population has previously been shown to detect evidence of neurodegeneration in MTL subregions and to help discriminate AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) from a healthy comparison group.

Methods

Clinical patients were selected and T2-weighted MRI scan quality was checked. An automatic segmentation method of hippocampal subfields (ASHS) was applied to scans of 67 AD patients, 38 amnestic MCI patients, and 57 healthy controls. Hippocampal subfields, entorhinal cortex (ERC), and perirhinal cortex were automatically labeled and subregion volumes were compared between groups.

Results

One fourth of all scans were excluded due to bad scan quality. There were significant volume reductions in all subregions, except BA36, in aMCIs (p < 0.001), most prominently in Cornu Ammonis 1 (CA1) and ERC, and in all subregions in AD. However, sensitivity of CA1 and ERC hardly differed from sensitivity of WH in aMCI and AD.

Conclusion

Applying automatic segmentation of MTL subregions in a clinical setting as a potential biomarker for prodromal AD is feasible, but issues of image quality due to motion remain to be addressed. CA1 and ERC provided strongest group discrimination in differentiating aMCIs from controls, but discriminatory power of different subfields was low overall.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, anatomy, biomarker, Cornu Ammonis, diagnosis, entorhinal cortex, hippocampus, hippocampal subfields, histology, magnetic resonance imaging, medial temporal lobe, mild cognitive impairment

INTRODUCTION

The capacity to monitor disease status and progression due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in its earliest symptomatic stage is of significant importance for interventions or disease-modifying pharmacotherapy. While cognitive measures are useful, confounding variables such as education and other lifestyle factors, which influence cognitive reserve, as well as age and gender differences, make this population extremely heterogeneous and a challenge for clinical and psychometric measures to track disease [1, 2]. In addition, there is evidence that spread of neurodegeneration in AD follows differential trajectories depending on the AD variant [3]. Therefore, there is great interest for introducing new biomarkers into daily clinical practice to facilitate the identification and monitoring of early stages and variants of AD [4, 5]. Notably, structural brain markers seem to be more sensitive to the disease stage and timing of progression in prodromal and dementia-level AD than molecular measures of cerebral amyloid-β (e.g., CSF Aβ or PET Pittsburgh compound B (PiB-PET) binding Aβ) [6–9]. Thus, structural imaging remains a potentially important biomarker in clinical practice and intervention studies.

A transitional state between normal cognition and clinical AD is described as mild cognitive impairment (MCI), which frequently represents a symptomatic, prodromal stage of AD or other forms of dementia. Patients with MCI have cognitive symptoms and signs but do not meet the diagnostic criteria for dementia [4, 10, 11]. Atrophy of medial temporal lobe (MTL) structures is associated with a decline in episodic memory, frequently seen in amnestic MCI patients converting to AD [12, 13].

In prodromal AD, neurodegenerative changes caused by neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) deposition are typically observed as a decrease in volume of MTL structures. Within the MTL, the earliest areas of NFT deposition are within the transentorhinal cortex (the medial wall of the perirhinal cortex) followed by the entorhinal cortex (ERC) and the first sector of the hippocampal subfield Cornu Ammonis (CA1) [14, 15]. Then atrophy spreads to other hippocampal subfields and parietal and frontal neocortices as the disease progresses [14, 16–18]. Because AD-related tau pathology affects MTL structures early and non-uniformly, medial temporal lobe subregion measurements may be more sensitive and specific to early disease changes than whole hippocampal measurements.

Several research studies have described results of manual, semi-automatic, and automatic segmentation of MTL subregions detecting volumetric changes [19–26]. These studies were performed in a controlled research environment with strict inclusion/exclusion criteria, well-defined imaging protocols, and trained magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technologists. However, so far none of these measurement methods have been applied to a more heterogeneous clinical memory center population and to MRI data acquired in a less controlled clinical setting.

Recently, Yushkevich et al. (2015) introduced a fully automated method for segmentation of MTL substructures in high-resolution T2-weighted coronal MRI, which was reliable when validated in a research population [25]. The aim of the present study is to determine the utility of this automated subregional MTL segmentation methodology in a clinical cohort to detect atrophy of MTL subregions. If successful, this approach has the potential to enhance discrimination between the early stages of AD, AD, and healthy controls in the clinical setting and provide a useful metric of disease progression. One potential concern in translation of the Yushkevich et al. technique to the clinical practice is that the quality of the T2-weighted MRI scans acquired can be significantly degraded by head motion, which we assessed in the current study to determine the feasibility of this technique in the clinical setting. Based on findings from previous studies on prodromal AD, we expected to find a strong pattern of atrophy in CA1 and ERC in MCI and a more diffuse pattern of atrophy in AD [26].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Patients were recruited from a large database of clinical patients at the Penn Memory Center (PMC)/Alzheimer’s disease Center of the University of Pennsylvania. 99 patients with the diagnoses AD and 56 patients with amnestic MCI (aMCI) were included in our study. All patients were diagnosed between 2010 and 2013 and had clinical neuroimaging. Diagnoses of AD and aMCI were determined at consensus conferences using standard clinical criteria for AD and aMCI [4, 5, 27]. Since no clinical 3T scans of healthy control subjects were available in the PMC clinical cohort, 67 healthy controls (HC) without cognitive complaints from a research study of aging and cognitive impairment, also conducted at PMC, were added to the study group. HC participants performed normally on age-adjusted cognitive measures. In addition, they were designated by the consensus group as ‘normal.’ General inclusion criteria were males and females over the age of 50, fluent in English, with (corrected) normal hearing/vision and no medical contraindications to MRI. Exclusion criteria were medical or neurological (movement) illnesses that could have primary impact on cognition outside of the neurodegenerative conditions of interest, significant prior head trauma, or substance abuse history.

All clinical patients at the PMC are queried about their interest in providing clinical material obtained as part of their evaluation to a research database and to be used for future research studies, as approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania.

MR-protocol

All clinical scans were acquired on a 3T Siemens Trio™ scanner at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania using an 8-channel array coil. A high-resolution T2-weighted fast spin echo sequence (TR/TE: 5310/68 ms, echo train length 15, 18.3 ms echo spacing, 150° flip angle, 0% phase over-sampling, 0.4 × 0.4 mm in plane resolution, 2 mm to 3.6 mm slice thickness, 30 interleaved slices often with 0.6 mm gap, acquisition time 7:12 min), angulated perpendicular to the long axis of the hippocampal formation, was used. There were some deviations from this exact protocol, resulting in some variation in slice thickness and the number of slices in the clinical scans, but the in-plane resolution was the same. The HC research scans were acquired on a research-dedicated Siemens 3T Trio™ scanner with the same scanning protocol [22].

Image selection

Hippocampal subfield structures and other MTL structures were inspected by an experienced rater (EG, first author) in all clinical and research T2-weighted MR scans. All scans showing severe motion artifacts, characterized by blurred lines in the MTL regions, or ringing artifacts were excluded. Of 222 subjects enrolled in the study, 67 AD patients, 38 aMCI patients, and 57 HCs were selected for automatic segmentation. 60 subjects were excluded because of bad scan quality.

Automatic segmentation

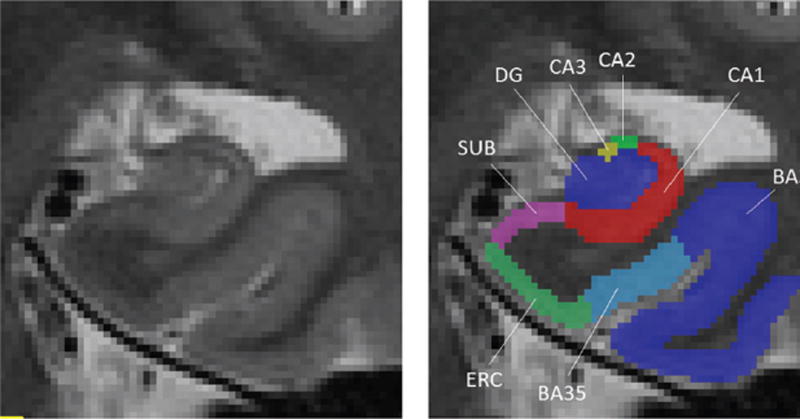

In this study, automatic labeling of MTL subregions in T2-weighted MR images was generated by the Automatic Segmentation of Hippocampal Sub-fields (ASHS; http://www.nitrc.org/projects/ashs) method [25]. ASHS applies deformable registration [28], multi-atlas label fusion [29], and machine learning [30] to propagate anatomical labels from a set of expert-labeled example MRI scans to a new unlabeled MRI scan. Figure 1 illustrates the automatic labeling of the hippocampal subfields Cornu Ammonis 1 (CA1), Cornu Ammonis 2 and 3 (CA2/CA3), dentate gyrus (DG), subiculum (SUB), and the cortical structures entorhinal cortex (ERC) and perirhinal cortex (Brodman areas (BA) 35 and 36) on a coronal slice of a T2-weighted MRI image.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of automatic segmentation of the right medial temporal lobe subfields in a coronal T2-weighted MRI scan. CA1, Cornu Ammonis 1; CA2, Cornu Ammonis 2; CA3, Cornu Ammonis 3; DG, dentate gyrus; SUB, subiculum; ERC, entorhinal cortex; BA35, Brodmann area 35; BA36, Brodmann area 36.

The expert segmentations leveraged by ASHS for multi-atlas segmentation were generated using the same protocol as described in Yushkevich et al.(2015). In that study, the agreement between automatic and manual volume measurements (interclass correlation coefficient, ICC) was quite high, especially in hippocampal subfields CA1 (ICC = 0.836) and DG (ICC = 0.893) as well as WH (ICC = 0.931) [25].

In that protocol, segmentation of CA1, CA2, CA3, and DG is performed along the entire anterior to posterior axis of the hippocampus (head, body, and tail). The segmentation of SUB is performed in the hippocampal head and the body, but not in the tail. ERC and PRC are segmented from one slice anterior to one slice posterior to the hippocampal head. The actual structures extend beyond these boundaries, but the protocol was not extended due to the complexity of the segmentation [25, 31, 32].

Automatic segmentation of medial temporal lobe subregions was performed in T2-weighted MRI images of 162 subjects. All automatic segmentations were visually inspected and no segmentation failures were detected. Thus, 162 subjects were chosen for statistical analysis. Volumes of CA1, DG, SUB, ERC, and PRC (BA35 and BA36) were calculated from automatic segmentation. Subfields CA2 and CA3 are small and less reliable based on previous analyses [22, 23, 25] and were thus not included in the current statistical analysis. Since the anterior and posterior boundaries of the ERC and PRC subfields were artificially truncated by the segmentation protocol, these volumes were normalized by the thickness of the slab in which they were segmented, as suggested in Yushkevich et al. [25]. Furthermore, ASHS reported an estimate of intracranial volume (ICV) based on deformable registration of the subject’s whole-brain T1-weighted MRI scans to a labeled template.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic variables age, gender, education, and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) of each group. Education and gender are known to influence brain reserve [33] and increased head size is associated with larger brain (subfield) volume, which can influence comparison between subjects and between groups [34]. Therefore, these variables were used as covariates and linear regression analyses were performed for each subfield separately to analyze the influence of these nuisance parameters on sub-field volumes. A repeated measures GLM analysis was conducted for each subfield separately showing that there was no statistically significant group × hemisphere interaction effect between left and right hemisphere in subfield volumes (except in BA36, F = 5.461, p = 0.035) after Bonferroni correction. As such, we decided that averaging the hemispheres was the most parsimonious approach.

To compare atrophy patterns of the MTL subregions, the residuals from the linear regression models were used for pair-wise group comparisons for each subfield, performed by unpaired t-tests. Finally, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and area under the curve (AUC) values were computed for aMCI and AD subgroups to investigate the practical differential value of automatic segmentation of MTL subfields in daily clinical practice.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

Demographic information of the final cohort of 57 HC, 38 aMCI patients, and 67 AD patients is presented in Table 1. The HC group was significantly younger than the AD group (F = 5.14; p < 0.01), but did not differ from the aMCI group in age. Also, the HC group was significantly higher educated than the AD group (F = 5.79; p < 0.01). No differences in gender between groups were observed (Chi-Square 5.34, df 2, p = 0.069). Furthermore, the HC group has significantly higher MMSE scores than the aMCI group and the AD group (F = 69.93, p < 0.001). Regression analysis showed a strong effect of age (p < 0.001) and also an effect of ICV (p < 0.05) but no effect of education and gender on all subregion volumes.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by diagnosis group

| Group | HC (n= 57) | aMCI (n=38) | AD (n= 67) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69.9 (9.2); 54–88 | 72.5 (6.9); 58–85 | 74.75 (8.4); 51–90* |

| Education (years) | 16.4 (2.9); 12–20 | 15.2 (3.2); 6–20 | 14.27 (3.6); 0–20* |

| MMSE score (/30) | 29.4 (0.9); 26–30 | 26.6 (2.7); 18–30** | 19.9 (5.3); 3–29** |

| Gender (Females %) | 57.9 | 52.6 | 73.1 |

Data are presented as Mean (standard deviation); Range, unless otherwise indicated. HC, healthy control; aMCI, amnestic mild cognitive impairment; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; MMSE, Mini-Mental Status Examination.

Significant different from HC, p < 0.01

Significant different from HC, p < 0.001.

Group comparisons of medial temporal lobe subregion volumes

Hippocampal subfield and cortical subregion volume measurements were made after automatic segmentation. Means and standard deviations of these measurements are presented in Table 2 for mean values of left and right hemisphere MTL subregion volumes.

Table 2.

Group comparisons

| Subfield | HC (n= 57) |

aMCI (n = 38) |

AD (n = 67) |

HC > aMCI | HC > AD | aMCI > AD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| t value | p | t value | p | t value | p | ||||

| CA1 | 1323.31 | 1041.04 | 950.72 | 5.71 | <0.001 | 8.74 | <0.001 | 0.98 | 0.328 |

| (in mm3) | (172.74) | (203.61) | (216.83) | ||||||

| DG | 746.22 | 625.81 | 529.79 | 3.82 | <0.001 | 8.34 | <0.001 | 2.85 | 0.006 |

| (in mm3) | (97.98) | (132.73) | (117.91) | ||||||

| SUB | 334.12 | 277.22 | 266.80 | 3.52 | 0.001 | 4.67 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.955 |

| (in mm3) | (48.02) | (57.05) | (65.30) | ||||||

| ERC* | 25.54 | 20.72 | 18.07 | 4.71 | <0.001 | 7.90 | <0.001 | 1.93 | 0.057 |

| (in mm2) | (4.01) | (4.12) | (3.97) | ||||||

| BA35* | 19.71 | 16.31 | 14.20 | 3.26 | 0.002 | 5.43 | <0.001 | 1.46 | 0.147 |

| (in mm2) | (3.83) | (4.01) | (4.21) | ||||||

| BA36* | 74.94 | 65.63 | 55.36 | 2.31 | 0.024 | 5.27 | <0.001 | 2.61 | 0.011 |

| (in mm2) | (13.78) | (14.62) | (14.15) | ||||||

| WH | 2403.66 | 1944.08 | 1747.31 | 5.29 | <0.001 | 8.78 | <0.001 | 1.50 | 0.138 |

| (in mm3) | (282.44) | (358.51) | (382.50) | ||||||

Data are presented as mean values of subfield volume measurements followed by standard deviations in parentheses. Group comparisons are presented t values and p values with p < 0.004 after Bonferroni correction. HC, healthy control; aMCI, amnestic mild cognitive impairment; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; CA1, Cornu Ammonis 1; DG, dentate gyrus; SUB, subiculum; ERC, entorhinal cortex; BA35, Brodman area 35; BA36, Brodman area 36; WH, whole hippocampus.

Volumes are normalized by the A-P extent of the segmentation.

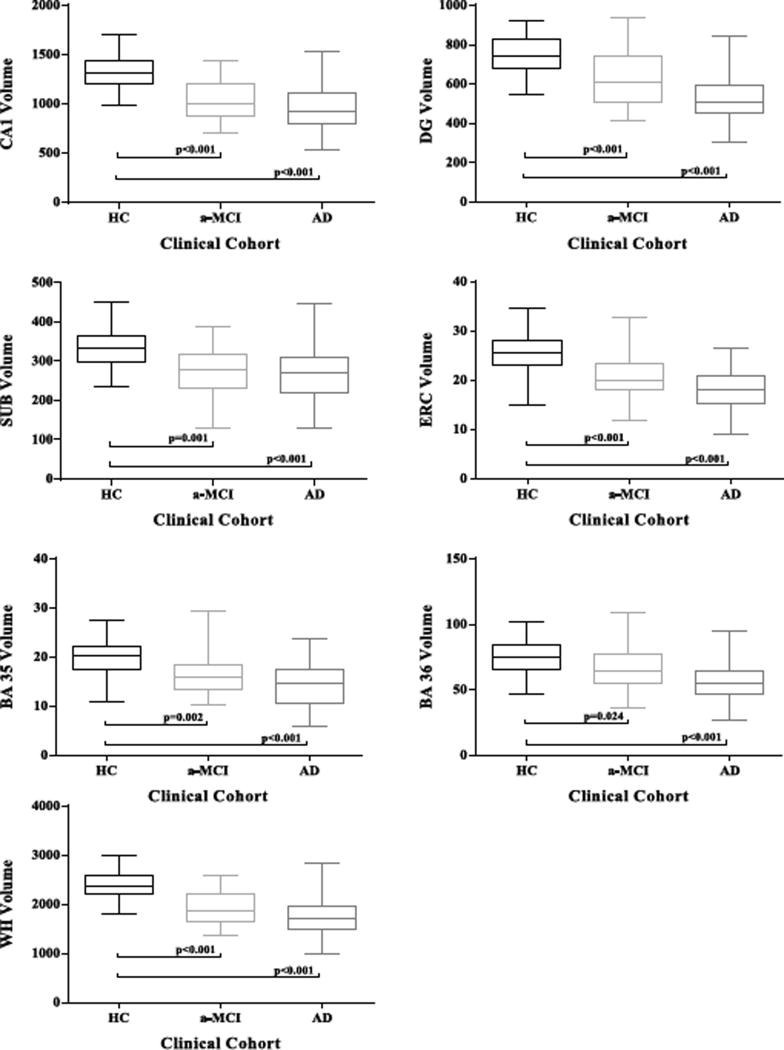

The group comparison statistics are also presented in Table 2. Results were corrected for multiple comparisons via Bonferroni correction. All hippocampal subfield volumes and cortical subregion volumes were significantly reduced in MCIs compared to HCs, except in the cortical region BA36 (Table 2 and Fig. 2). In AD, strong differences (p < 0.001) were measured in all subregions. There were no significant differences between aMCI and AD in all subfields.

Fig. 2.

Group comparisons for all subfield volumes. HC, healthy control; aMCI, amnestic mild cognitive impairment; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; CA1, Cornu Ammonis 1; DG, dentate gyrus; SUB, subiculum; ERC, entorhinal cortex; BA35, Brodman area 35; BA36, Brodman area 36; WH, whole hippocampus.

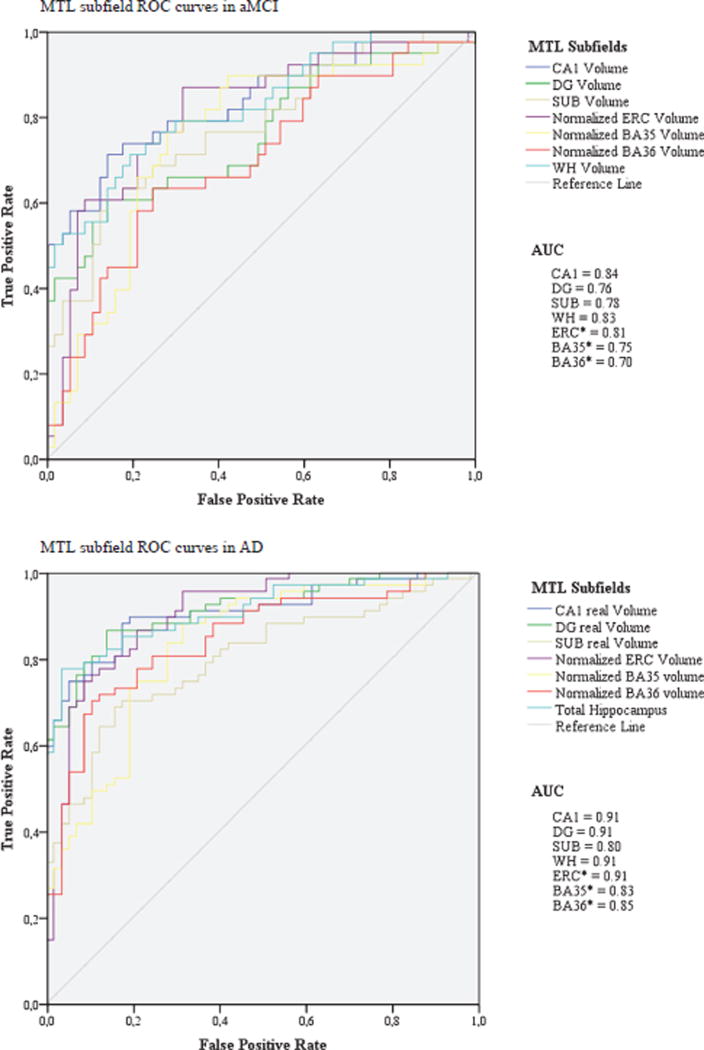

To investigate individual-level statistics, we analyzed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and area under the curve (AUC) values in the aMCI group and the AD group separately (Fig. 3). In aMCI CA1 subfield had the highest AUC (0.84), followed by WH (AUC: 0.83) and ERC (AUC 0.81). In the AD group CA1, DG, WH, and ERC had all the same AUCs of 0.91.

Fig. 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and area under the curve (AUC) values for MTL subfields in aMCI versus HC, and AD versus HC. AUC = 0.5 (discrimination no better than chance), AUC = 1 (perfect discrimination); *normalized MTL structures.

DISCUSSION

Measuring MTL sub-regional volumes in preclinical and prodromal AD could not only be important for diagnosis, but for understanding the progression of disease or how different factors such as APOE or tau/Aβ contribute to this progression. Furthermore, a better understanding of subfield atrophy patterns may help explaining cognitive deficits or even relations with inflammatory processes in the brain [35].

Selective involvement of MTL regions has been supported by pathological research in which neuronal counts and volumes decrease in AD relative to age-matched cognitively normal individuals [36, 37]. In addition, our prior work and that of others have provided support for the notion that measurement of specific subfield volumes is associated with increased sensitivity to prodromal AD or MCI relative to whole hippocampal measurements [22, 25, 38].

Most patients with cognitive symptoms and suspected AD undergo standard structural imaging with MRI in daily clinical practice, usually to rule out other causes of cognitive decline. Therefore, the T2-weighted MRI images can be easily used for automatic segmentation. As the T2-weighted sequence described here can be obtained on standard MRI platforms and takes <7 minutes, this sequence could be easily implemented as part of routine clinical work-up and easily utilized for automatic segmentation of MTL subregions, providing a more precise biomarker for identifying structural changes in prodromal AD.

The current study primarily investigated the potential utility of automatic segmentations of MTL subregions in clinical patients. The ASHS method detected subregion-specific changes in clinical T2-weighted MRI similar to results from previous research studies [22, 25]. In our study, regional volume loss was identified in all MTL subregions, except BA36, in aMCI and in all MTL subregions in AD. Atrophy in CA1 and ERC regions was most predictive in aMCI subjects, a stage when more selective MTL involvement is expected. Notably, the sensitivity for CA1 was slightly stronger than whole hippocampal measurement, supporting the potential benefit of this more granular measurement in this population. This finding is consistent with results from an earlier study using the same segmentation atlas in a research population [25], as well as the literature about neuropathology, which describes earliest NFT deposition in these areas [14, 16, 39]. Additionally, other segmentation protocols, both manual and automated have similarly found advantages for select hippocampal subregions, CA1 or CA1-2, relative to whole hippocampal volume [22, 40, 41]. Compared to the current study findings, Yushkevich et al. (2015) detected slightly stronger early changes in PRC areas BA35 and BA36 in aMCIs in a research population. We suspect that this is due to increased noise and variability in image quality of the clinical scans, in part related to greater issues with subject motion in this population.

However, to look at the discriminatory power of subregional measurements in this clinical population of aMCIs and therefore the potential utility in future daily clinical practice, individual-level statistics were compared. This analysis demonstrated that differences between sensitivity of CA1 and WH are minimal, which is shown by the additional ROC statistics (CA1: AUC=0.84; WH: AUC=0.83). This does seem consistent with the idea that CA1 is likely a major driver of atrophy in WH in MCI while both CA1 and DG may more equally drive WH atrophy in AD. This raises the question if subfield measurements would have enough discriminatory power in a clinical population to be implemented in future daily clinical practice.

In the current study, the AD population displayed relatively strong group differences with controls for all MTL regions, which likely reflected the broad range of severity of this group (MMSE range 3 to 29). It is likely by more severe stages of AD that MTL involvement is diffuse and that selective hippocampal subregional measurement may not yield enhanced discriminatory power beyond a summary measure, such as whole hippocampal volumes, in AD. This has been confirmed by ROC curve analyses. In AD there were no differences between hippocampal subfields and whole hippocampus in AUCs at all, probably as the atrophy was so severe. Notably, in our study whole hippocampal volumes were the sum of hippocampal subfield volumes rather than the more traditional measure obtained by segmentation of T1-weighted MRI. It has previously been shown that discriminatory results from whole hippocampal volumes measured in T2-weighted MRIs are similar to segmentation measurements from T1-weighted MRI scans [25]. Importantly, the error in whole hippocampal volume measurements tends to be lower than segmenting individual subfields, particularly the smaller ones, which may contribute to its sensitivity to disease. But improved imaging, motion correction, and segmentation would likely enhance subfield measures, which would further enhance discrimination relative to whole hippocampal volumes, particularly in prodromal stages of disease. That said, as AD progresses, measurement of these regions will have diminishing value, as there is much more diffuse MTL involvement in dementia stages. Therefore, this technique might also not be the ideal method for measuring disease progression in the more severe stages.

Even though specific subfields may not provide strong differential sensitivity to prodromal or dementia-level AD, they may provide better specificity to the cognitive deficits that define prodromal or dementia-level AD. A rich memory literature has suggested that different subregions of the MTL support different memory representations or processes. For example, we might expect that the degree to which there is atrophy of CA1, the greater deficits would be in memory retrieval. Alternatively, DG differences may modulate measures of pattern separation. However, to which extent this impairment is due to AD pathology, vascular disease, or aging is speculative, as it has been investigated that elevated vascular risk and smaller CA1 volume predicted variance in delayed recall and CA1 atrophy is also associated with aging [35, 42, 43]. Further research on this could address this issue. In addition, this method might be helpful to distingue between AD and dementia with Lewy bodies [44, 45]. In AD, a stronger CA1 atrophy is expected and could therefore be a biomarker for distinction between those two diseases. Also, the combination with FDG biomarkers, which are thought to give complementary information about disease progression, would be interesting in future clinical practice and intervention studies [46].

A weakness of this methodology is that automatic segmentation of T2-weighted images requires reasonable quality to detect subfield boundaries reliably and is very sensitive to subject motion. In this study, about one-fourth of all images had to be excluded because of motion artifacts and poor image quality. This is a much higher percentage than recently reported using the same methodology in a purely research cohort (6.5% of images were excluded) [25]. Notably, most of the images that needed to be excluded were from AD patients, due to movement during the scanning process. While T1-weighted scans are more robust and less sensitive to motion, they are less suitable for subfield boundary discrimination. However, this problem might be solved in the future, because on-scanner motion correction systems (http://www.kineticor.com/) have been developed recently [47]. In addition, involvement of an expert in the scan selection in daily clinical practice is a weak link. So far, our software itself cannot determine whether a scan has high or low quality or a segmentation was a success or failure. However, with regard to selection of images with high versus low quality, Mortamet et al. (2009) have developed a fully automatic method for detection of artifacts in structural MRIs. Their method has been validated on T1-weighted 1.5 T and 3 T head scans from ADNI and correlated well with quality ratings from an independent gold standard source (sensitivity and specificity >85%). According to the authors, the selection of cutoff points could be application-specific and extended to other contrasts. This method might speed up the selection of scans for automatic segmentation replacing an expert [48].

Another limitation of this study is that the present control group was obtained under research conditions, and scans were of particularly high quality relative to the clinical scans. This may skew the potential discriminatory value of these measures in relation to a clinical control population.

CONCLUSION

Applying automatic segmentation of MTL structures in a clinical setting as a potential biomarker for prodromal AD is feasible, but issues of image quality in high-resolution T2-weighted scans remain to be addressed. Even though CA1 and ERC provided the largest group differences between aMCIs and controls in absolute terms, there was not a clear statistical difference between these subfields and the whole hippocampus in this cohort. Leveraging the advantage of subfield measures in clinical populations, as was shown previously in research cohorts, will likely require improvements to image quality and image analysis. Future studies will also need to determine the relative value of this approach in diagnosis, assessing cognitive deficits and mainly its use in addition to other biomarkers in the clinical setting.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants AG037376, AG028018, AG010124 and grant EB017255.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/16-0014r1).

References

- 1.Snyder PJ, Kahle-Wrobleski K, Brannan S, Miller DS, Schindler RJ, DeSanti S, Ryan JM, Morrison G, Grundman M, Chandler J, Caselli RJ, Isaac M, Bain L, Carrillo MC. Assessing cognition and function in Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials: Do we have the right tools? Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:853–860. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.07.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tucker AM, Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in aging. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2011;8:354–360. doi: 10.2174/156720511795745320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ossenkoppele R, Cohn-Sheehy BI, La Joie R, Vogel JW, Moller C, Lehmann M, van Berckel BN, Seeley WW, Pijnenburg YA, Gorno-Tempini ML, Kramer JH, Barkhof F, Rosen HJ, van der Flier WM, Jagust WJ, Miller BL, Scheltens P, Rabinovici GD. Atrophy patterns in early clinical stages across distinct phenotypes of Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:4421–4437. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Snyder PJ, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Jr, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sluimer JD, Bouwman FH, Vrenken H, Blankenstein MA, Barkhof F, van der Flier WM, Scheltens P. Whole-brain atrophy rate and CSF biomarker levels in MCI and AD: A longitudinal study. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:758–764. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickerson BC, Wolk DA. Biomarker-based prediction of progression in MCI: Comparison of AD signature and hippocampal volume with spinal fluid amyloid-beta and tau. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:55. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jack CR, Jr, Lowe VJ, Weigand SD, Wiste HJ, Senjem ML, Knopman DS, Shiung MM, Gunter JL, Boeve BF, Kemp BJ, Weiner M, Petersen RC. Serial PIB and MRI in normal, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: Implications for sequence of pathological events in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2009;132:1355–1365. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jack CR, Jr, Wiste HJ, Vemuri P, Weigand SD, Senjem ML, Zeng G, Bernstein MA, Gunter JL, Pankratz VS, Aisen PS, Weiner MW, Petersen RC, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Knopman DS. Brain beta-amyloid measures and magnetic resonance imaging atrophy both predict time-to-progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2010;133:3336–3348. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Geda YE, Ivnik RJ, Smith GE, Jack CR., Jr Mild cognitive impairment: Ten years later. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1447–1455. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, Nordberg A, Backman L, Albert M, Almkvist O, Arai H, Basun H, Blennow K, de Leon M, DeCarli C, Erkinjuntti T, Giacobini E, Graff C, Hardy J, Jack C, Jorm A, Ritchie K, van Duijn C, Visser P, Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment-beyond controversies, towards a consensus: Report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256:240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudon C, Belleville S, Gauthier S. The assessment of recognition memory using the Remember/Know procedure in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and probable Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Cogn. 2009;70:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belleville S, Fouquet C, Duchesne S, Collins DL, Hudon C. Detecting early preclinical Alzheimer’s disease via cognition, neuropsychiatry, and neuroimaging: Qualitative review and recommendations for testing. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(Suppl 4):S375–S382. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez-Isla T, Price JL, McKeel DW, Jr, Morris JC, Grow-don JH, Hyman BT. Profound loss of layer II entorhinal cortex neurons occurs in very mild Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4491–4500. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04491.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.West MJ, Coleman PD, Flood DG, Troncoso JC. Differences in the pattern of hippocampal neuronal loss in normal ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 1994;344:769–772. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92338-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald CR, McEvoy LK, Gharapetian L, Fennema-Notestine C, Hagler DJ, Jr, Holland D, Koyama A, Brewer JB, Dale AM. Regional rates of neocortical atrophy from normal aging to early Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;73:457–465. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b16431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scahill RI, Schott JM, Stevens JM, Rossor MN, Fox NC. Mapping the evolution of regional atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease: Unbiased analysis of fluid-registered serial MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4703–4707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052587399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim HK, Hong SC, Jung WS, Ahn KJ, Won WY, Hahn C, Kim IS, Lee CU. Automated segmentation of hippocampal subfields in drug-naive patients with Alzheimer disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:747–751. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mueller SG, Stables L, Du AT, Schuff N, Truran D, Cashdollar N, Weiner MW. Measurement of hippocampal subfields and age-related changes with high resolution MRI at 4T. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:719–726. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mueller SG, Weiner MW. Selective effect of age, Apo e4, and Alzheimer’s disease on hippocampal subfields. Hippocampus. 2009;19:558–564. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pluta J, Yushkevich P, Das S, Wolk D. In vivo analysis of hippocampal subfield atrophy in mild cognitive impairment via semi-automatic segmentation of T2-weighted MRI. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;31:85–99. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yushkevich PA, Wang H, Pluta J, Das SR, Craige C, Avants BB, Weiner MW, Mueller S. Nearly automatic segmentation of hippocampal subfields in in vivo focal T2-weighted MRI. Neuroimage. 2010;53:1208–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Leemput K, Bakkour A, Benner T, Wiggins G, Wald LL, Augustinack J, Dickerson BC, Golland P, Fischl B. Automated segmentation of hippocampal subfields from ultra-high resolution in vivo MRI. Hippocampus. 2009;19:549–557. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yushkevich PA, Pluta JB, Wang H, Xie L, Ding SL, Gertje EC, Mancuso L, Kliot D, Das SR, Wolk DA. Automated volumetry and regional thickness analysis of hippocampal subfields and medial temporal cortical structures in mild cognitive impairment. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:258–287. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perrotin A, de Flores R, Lamberton F, Poisnel G, La Joie R, de la Sayette V, Mezenge F, Tomadesso C, Landeau B, Desgranges B, Chetelat G. Hippocampal subfield volumetry and 3D surface mapping in subjective cognitive decline. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48(Suppl 1):S141–S150. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256:183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avants BB, Epstein CL, Grossman M, Gee JC. Symmetric diffeomorphic image registration with cross-correlation: Evaluating automated labeling of elderly and neurodegenerative brain. Med Image Anal. 2008;12:26–41. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hongzhi W, Suh JW, Das SR, Pluta JB, Craige C, Yushkevich PA. Multi-atlas segmentation with joint label fusion. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2013;35:611–623. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2012.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang H, Das SR, Suh JW, Altinay M, Pluta J, Craige C, Avants B, Yushkevich PA. A learning-based wrapper method to correct systematic errors in automatic image segmentation: Consistently improved performance in hippocampus, cortex and brain segmentation. Neuroimage. 2011;55:968–985. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ding SL, Van Hoesen GW. Borders, extent, and topography of human perirhinal cortex as revealed using multiple modern neuroanatomical and pathological markers. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31:1359–1379. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adler DH, Pluta J, Kadivar S, Craige C, Gee JC, Avants BB, Yushkevich PA. Histology-derived volumetric annotation of the human hippocampal subfields in postmortem MRI. Neuroimage. 2014;84:505–523. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stern Y, Gurland B, Tatemichi TK, Tang MX, Wilder D, Mayeux R. Influence of education and occupation on the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. JAMA. 1994;271:1004–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barnes J, Ridgway GR, Bartlett J, Henley SM, Lehmann M, Hobbs N, Clarkson MJ, MacManus DG, Ourselin S, Fox NC. Head size, age and gender adjustment in MRI studies: A necessary nuisance? Neuroimage. 2010;53:1244–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raz N, Daugherty AM, Bender AR, Dahle CL, Land S. Volume of the hippocampal subfields in healthy adults: Differential associations with age and a proinflammatory genetic variant. Brain Struct Funct. 2015;220:2663–2674. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0817-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simic G, Kostovic I, Winblad B, Bogdanovic N. Volume and number of neurons of the human hippocampal formation in normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease. J Comp Neurol. 1997;379:482–494. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970324)379:4<482::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossler M, Zarski R, Bohl J, Ohm TG. Stage-dependent and sector-specific neuronal loss in hippocampus during Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2002;103:363–369. doi: 10.1007/s00401-001-0475-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chupin M, Gerardin E, Cuingnet R, Boutet C, Lemieux L, Lehericy S, Benali H, Garnero L, Colliot O. Fully automatic hippocampus segmentation and classification in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment applied on data from ADNI. Hippocampus. 2009;19:579–587. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bobinski M, de Leon MJ, Tarnawski M, Wegiel J, Reisberg B, Miller DC, Wisniewski HM. Neuronal and volume loss in CA1 of the hippocampal formation uniquely predicts duration and severity of Alzheimer disease. Brain Res. 1998;805:267–269. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00759-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mueller SG, Schuff N, Yaffe K, Madison C, Miller B, Weiner MW. Hippocampal atrophy patterns in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31:1339–1347. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.La Joie R, Perrotin A, de La Sayette V, Egret S, Doeuvre L, Belliard S, Eustache F, Desgranges B, Chetelat G. Hippocampal subfield volumetry in mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease and semantic dementia. Neuroimage Clin. 2013;3:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bender AR, Daugherty AM, Raz N. Vascular risk moderates associations between hippocampal subfield volumes and memory. J Cogn Neurosci. 2013;25:1851–1862. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shing YL, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Fandakova Y, Bodammer N, Werkle-Bergner M, Lindenberger U, Raz N. Hippocampal subfield volumes: Age, vascular risk, and correlation with associative memory. Front Aging Neurosci. 2011;3:2. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2011.00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mak E, Su L, Williams GB, Watson R, Firbank M, Blamire AM, O’Brien JT. Longitudinal assessment of global and regional atrophy rates in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neuroimage Clin. 2015;7:456–462. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mak E, Su L, Williams GB, Watson R, Firbank M, Blamire A, O’Brien J. Differential atrophy of hippocampal subfields: A comparative study of dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24:136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Besson FL, La Joie R, Doeuvre L, Gaubert M, Mezenge F, Egret S, Landeau B, Barre L, Abbas A, Ibazizene M, de La Sayette V, Desgranges B, Eustache F, Chetelat G. Cognitive and brain profiles associated with current neuroimaging biomarkers of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2015;35:10402–10411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0150-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Callaghan MF, Josephs O, Herbst M, Zaitsev M, Todd N, Weiskopf N. An evaluation of prospective motion correction (PMC) for high resolution quantitative MRI. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:97. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mortamet B, Bernstein MA, Jack CR, Jr, Gunter JL, Ward C, Britson PJ, Meuli R, Thiran JP, Krueger G. Automatic quality assessment in structural brain magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:365–372. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]