Abstract

Cyanidin, a key flavonoid that is present in red berries and other fruits, attenuates the development of several diseases, including asthma, diabetes, atherosclerosis, and cancer, through its anti-inflammatory effects. We investigated the molecular basis of cyanidin action. Through a structure-based search for small molecules that inhibit signaling by the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-17A (IL-17A), we found that cyanidin specifically recognizes an IL-17A binding site in the IL-17A receptor subunit (IL-17RA) and inhibits the IL-17A/IL-17RA interaction. Experiments with mice demonstrated that cyanidin inhibited IL-17A–induced skin hyperplasia, attenuated inflammation induced by IL-17–producing T helper 17 (TH17) cells (but not that induced by TH1 or TH2 cells), and alleviated airway hyperreactivity in models of steroid-resistant and severe asthma. Our findings uncover a previously uncharacterized molecular mechanism of action of cyanidin, which may inform its further development into an effective small-molecule drug for the treatment of IL-17A–dependent inflammatory diseases and cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Interleukin-17A (IL-17A) is a signature cytokine of T helper 17 (TH17) cells, a CD4+ T cell subset that regulates tissue inflammatory responses (1). Tremendous effort has been devoted to understand the function of IL-17A, demonstrating that this proinflammatory cytokine plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases, metabolic disorders, and cancer (2–5). IL-17A signals through the IL-17 receptor (IL-17R) complex that consists of the IL-17RA and IL-17RC subunits to transmit signals into cells (6). The main function of IL-17A is to coordinate local tissue inflammation through increasing the amounts of proinflammatory and neutrophil-mobilizing cytokines and chemokines that are produced. Deficiency in IL-17A signaling components attenuates the pathogenesis of several autoimmune inflammatory diseases, including asthma, psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), and tumorigenesis in animal models (2, 3, 5, 7–13). High amounts of IL-17A are found in bronchial biopsies and serum obtained from patients with severe asthma, synovial fluids from arthritis patients, serum and brain tissue of multiple sclerosis patients, skin lesions of psoriasis patients, and the serum and tumor tissues of cancer patients (14–17). Targeting the binding of IL-17A to IL-17RA is reported to be an effective strategy for treating IL-17A–mediated autoimmune inflammatory diseases (1, 18). An anti–IL-17A antibody (Cosentyx, also known as secukinumab) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of psoriasis, and it is currently being used in 50 clinical trials for various autoimmune diseases (18–25).

Much effort has been devoted to develop more cost-effective alternative therapies, such as small-molecule drugs, to inhibit IL-17A. Natural products and their derivatives play a substantial role in the small-molecule drug discovery and development process (26). For example, aspirin, one of the oldest and most widely used drugs, was derived from the herbs meadowsweet and willow bark; Mevacor (lovastatin), a well-known cholesterol-lowering drug that acts as an HMG-CoA (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A) reductase inhibitor, was originally isolated from a strain of Aspergillus terreus. Furthermore, many natural products serve as prototypes for synthetic drug development. The invention of the drug Lipitor (atorvastatin), the best-selling small-molecule drug in the world, was built on the discovery of the fungal metabolite–derived inhibitors mevastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, and simvastatin. The rate of new chemical entity approvals demonstrates that the natural product field is involved in about 40% of all small molecules discovered in the past 15 years.

Here, we identified a potent small-molecule compound, A18 (a natural product also called cyanidin), as an IL-17A inhibitor through computer-aided, docking-based virtual screening. Cyanidin is a key pigment present in red berries and other fruits, which has been implicated in attenuating the development of several major diseases, including asthma, diabetes, atherosclerosis, and cancer, by stimulating anti-inflammatory effects through as yet unknown mechanisms. Through biochemical and mutagenesis studies, we showed that A18 specifically bound to a region in the extracellular domain of IL-17RA that overlaps with the binding site for IL-17A and that this binding potently disrupted formation of the IL-17A/IL-17RA complex. We demonstrated that A18 effectively inhibited IL-17A–dependent skin hyperplasia and neutrophilia; attenuated TH17 cell–induced, but not TH1 cell– or TH2 cell–induced, inflammation; and alleviated airway hyperreactivity (AHR) in mouse models of steroid-resistant and severe asthma. These results uncover a previously uncharacterized molecular basis for the cyanidin-mediated reduction of inflammation by specifically inhibiting the IL-17A/IL-17RA pathway. The findings suggest that A18 may be used as a prototype for the development of small-molecule drugs to treat IL-17A–mediated inflammatory diseases and cancer.

RESULTS

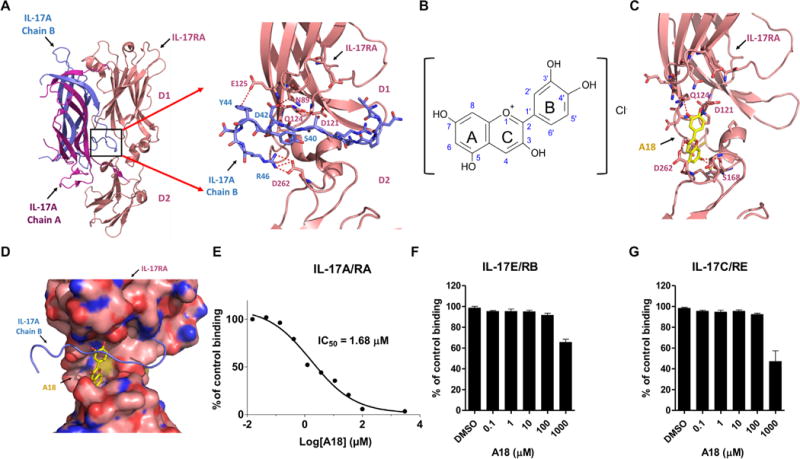

The small-molecule A18 specifically inhibits the binding of IL-17A to IL-17RA

The crystal structure of the extracellular domain of human IL-17RA complexed with an IL-17A homodimer has been solved (27). IL-17RA, which is composed of two fibronectin type III domains (D1 and D2) (Fig. 1A), forms an extensive binding interface with IL-17A, which contains three major interaction sites (27). In particular, the amino acid residues of IL-17RA that interact with the segment of IL-17A consisting of residues 35 to 46 form a deep binding pocket, which is optimal for drug targeting (Fig. 1A). This pocket consists of residues from Asn89 (N89) to Glu92 (E92) and Asp121 (D121) to Glu125 (E125) of the D1 domain, Ser257 (S257) to Asp262 (D262) of the D2 domain, and a small helix linker [residues Thr163 (T163) to Ser167 (S167)] that connects the D1 and D2 domains. We performed computer-aided, docking-based virtual screening of this pocket (as shown in the black box in Fig. 1A) to search for small-molecule inhibitors capable of disrupting the IL-17A/IL-17RA interaction. The public compound database [National Cancer Institute (NCI) Plated 2007 and NCI Diversity 3)] containing ~0.1 million compounds was virtually screened. We eventually selected and purchased 64 compounds for testing by bioactivity assay. One promising candidate (A18) exhibited excellent inhibition efficacy for IL-17A/IL-17RA binding (Fig. 1, B to E) and docked into the IL-17RA pocket by forming potential contacts with residues Asp121 (D121), Gln124 (Q124), Ser168 (S168), and Asp262 (D262) (Fig. 1C), which are mutually exclusive with the IL-17RA residues that interact with IL-17A (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1. The small-molecule A18 specifically inhibits the binding of IL-17A to IL-17RA.

(A) Crystal structures of the IL-17A/IL-17RA complex [Protein Data Bank (PDB) 4HSA] and a magnified view of the binding interface (boxed region) indicating the deep ligand-binding pocket (defined in the text) with a cluster of hydrophilic residues highlighted at the interface. Chains A and B of IL-17A are shown in magenta and blue, respectively. The D1 and D2 domains of IL-17RA are shown in coral. (B) Chemical structure of A18. (C) Docking of A18 to the IL-17RA binding pocket. Red dashed lines indicate potential hydrogen bonds formed between A18 and critical amino acid residues in the docking pocket of IL-17RA. (D) Superimposition of the structures of IL-17A (blue) and A18 (yellow) onto the structure of the binding pocket of IL-17RA (pink). The binding mode of A18 was generated by docking. IL-17RA is shown in surface representation. (E to G) Analysis of the effects of the indicated concentrations of A18 on the extent of binding of IL-17RA–Fc to IL-17A (E), IL-17RB–Fc to IL-17E (F), and IL-17RE–Fc to IL-17C (G). The extent of binding inhibition by A18 was expressed as a percentage of the binding of the appropriate ligand to the indicated receptor in the absence of A18 [dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) control], which was set at 100%. Data are means ± SEM of three independent experiments.

The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) name of A18 is 2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-3,5,7-trihydroxy-1-benzopyrylium chloride. The core of A18 (also called cyanidin, a particular form of anthocyanidins in the flavonoid superfamily) has the typical C6–C3–C6 flavonoid skeleton, which contains one heterocyclic benzopyran ring (known as the C ring), one fused aromatic ring (the A ring), and one phenyl constituent (the B ring) (Fig. 1B). In the cationic form, anthocyanidins have two double bonds in the C ring and hence carry a positive charge. To test the ability of A18 to disrupt IL-17A/IL-17RA binding, we coated purified IL-17A, IL-17E, and IL-17C onto 96-well plates, which was followed by the addition of IL-17RA–Fc, IL-17RB–Fc, and IL-17RE–Fc, respectively, together with serial dilutions of A18. Those receptors that bound to the ligands were detected with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated anti-Fc antibody. A18 showed inhibition efficacy for IL-17A/IL-17RA binding with a median inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 1.68 μM (Fig. 1E), but it did not efficiently disrupt IL-17E/IL-17RB or IL-17C/IL-17RE binding (Fig. 1, F and G).

Consistent with the competition assays, our docking studies showed that A18 and IL-17A shared overlapping binding sites on IL-17RA (Fig. 1, C and D). The sequences of human and mouse IL-17RA are highly conserved (fig. S1A). Among the amino acid residues of IL-17RA that make contact with both chains A and B of IL-17, Asp262 is a key residue located in the docking pocket of IL-17RA (fig. S1, A and B). Note that Asp262 is conserved in human and mouse IL-17RA. To further experimentally characterize the binding of A18 to IL-17RA, we measured the binding affinity [dissociation constant (Kd)] of the A18/IL-17RA interaction, which was found to be ~3 μM (fig. S1C) based on a fluorescence quenching assay (see Materials and Methods for details). Mutation of the putative binding residue Asp262 (based on our docking structure) in IL-17RA reduced its binding affinity for A18 (Kd = 6.35 μM) (fig. S1C). The same D262A mutation also reduced the binding affinity of IL-17RA for IL-17A (Kd was changed from 0.37 μM for the wild-type (WT) receptor to 1.57 μM for the D262A mutant) (fig. S1D). In an independent experiment using surface plasmon resonance (SPR), we confirmed the binding of A18 to IL-17RA (fig. S1E). These biochemical data suggest that A18 and IL-17A share the same binding site in IL-17RA, which provides the basis for how A18 inhibits the IL-17A/IL-17RA interaction.

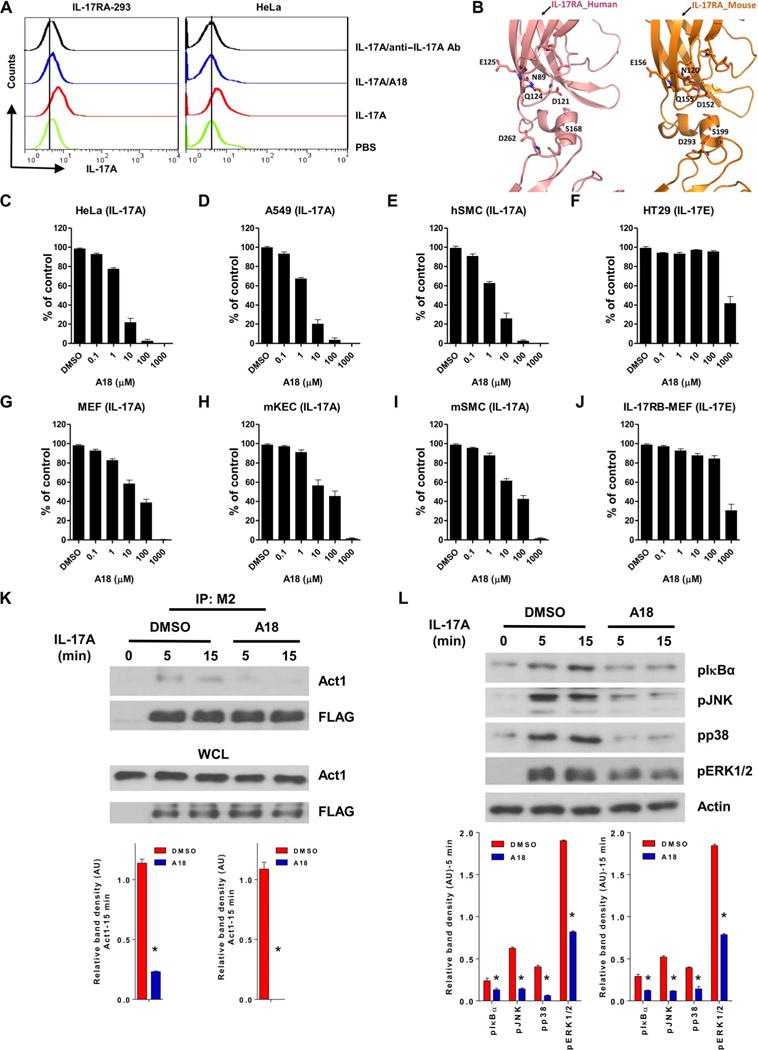

A18 specifically inhibits IL-17A–induced gene expression in human and mouse cells

Because A18 blocked the IL-17A/IL-17RA interaction in biochemical assays with purified proteins, we further investigated whether A18 was capable of inhibiting the binding of IL-17A to IL-17RA on live cells. We incubated human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells expressing IL-17RA (IL-17RA–239) and HeLa cells (which have endogenous receptors for IL-17A) with biotinylated IL-17A in the presence of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; negative control), A18, or anti-human IL-17A antibody (positive control), followed by incubation with avidin-fluorescein and analysis by flow cytometry. The results showed that A18 inhibited the binding of IL-17A to either ectopically expressed or endogenous IL-17RA (Fig. 2A). The amino acid residues in the docking pocket are conserved between human and mouse receptors (Fig. 2B). We next examined whether A18 exhibited an inhibitory effect on IL-17A activity in cultured human and mouse cells. We found that A18 substantially inhibited the IL-17A–stimulated production of multiple cytokines and chemokines [including CXCL1 (also known as GROα), IL-6, and IL-8 in human cells and CXCL1 (also known as KC), IL-6, and CXCL2 (also known as MIP-2) in mouse cells], whereas A18 showed limited inhibitory activity against the IL-17E–stimulated production of CXCL1 only at the highest concentration (Fig. 2, C to J, and fig. S2, A to D). IL-17A–mediated signaling events, including the recruitment of the adaptor protein Act1 to IL-17RA and the phosphorylation of inhibitor of nuclear factor κB α (IκBα) and of the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), p38, and extracellular signal–regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), were also decreased in the presence of A18 (Fig. 2, K and L).

Fig. 2. A18 specifically inhibits IL-17A–induced gene expression and signaling in human and mouse cells.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of HEK 293 cells stably expressing IL-17RA (IL-17RA–293; left) and HeLa cells (right) incubated with PBS or with biotinylated IL-17A in the presence of PBS, A18, or anti-human IL-17A antibody. Cells were incubated with avidin-fluorescein before being subjected to flow cytometric analysis. Data are representative of three experiments. (B) Comparison of the binding pockets of human (left) and mouse (right) IL-17RA. The model of mouse IL-17RA was generated with I-TASSER software (50). (C to J) The indicated human (C to F) and mouse (G to J) cell types were treated for 24 hours with IL-17A or IL-17E, as indicated, in the presence of DMSO (vehicle control) or the indicated concentrations of A18. The concentrations of CXCL1 (GROα in humans and KC in mice) in the culture medium were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Results are presented as a percentage of the amount of CXCL1 in the culture medium of IL-17–stimulated, DMSO-treated cells, which was set at 100%. Data are representative of four independent experiments. Error bars represent the SEM of technical replicates. (K) HeLa cells were transfected with plasmid encoding FLAG-tagged WT IL-17RA. Forty-eight hours later, the cells were pretreated with DMSO or 10 μM A18 before being incubated for the indicated times with IL-17A. Top: Whole-cell lysates (WCLs) were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with an anti-FLAG antibody (M2) and then were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-Act1 and anti-FLAG antibodies. Western blots are representative of three independent experiments. Bottom: The relative densities of the bands corresponding to Act1 in the immunoprecipitated samples were normalized to those in the WCLs. Data are means ± SEM of three independent experiments. (L) HeLa cells were pretreated for 1 hour with DMSO or 10 μM A18 before they were treated for the indicated times with IL-17A. The cells were then analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against the indicated proteins. Top: Western blots are representative of three independent experiments. Bottom: The relative densities of the bands corresponding to pIκBα, pJNK, pp38, and pERK1/2 were normalized to that of actin. Data are means ± SEM of three independent experiments. hSMC, human smooth muscle cell; mSMC, mouse smooth muscle cell; mKEC, mouse kidney epithelial cell. AU, arbitrary units. *P < 0.05 when comparing DMSO-treated cells with A18-treated cells.

Analysis of the crystal structure of IL-17RA showed that IL-17F, similar to IL-17A, also interacted with IL-17RA through the docking pocket discussed earlier (28). We found that A18 also inhibited the IL-17F– and IL-17A/IL-17F–stimulated expression of target genes in cultured cells (fig. S2, E and F). In contrast, A18 had little effect on the IL-17E–induced expression of target genes in the IL-17E–responsive cells HT29 and IL-17RB–expressing mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (Fig. 2, F and J). These data suggest that A18 does not stimulate receptor internalization because IL-17E also uses IL-17RA to transduce signals. In the case of gene expression induced by other cytokines, such as IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor, A18 showed inhibitory activity only at very high concentrations (>100 μM) (fig. S2, G and H). These results suggest that A18 specifically blocks IL-17A activity in cultured cells in a dose-dependent manner.

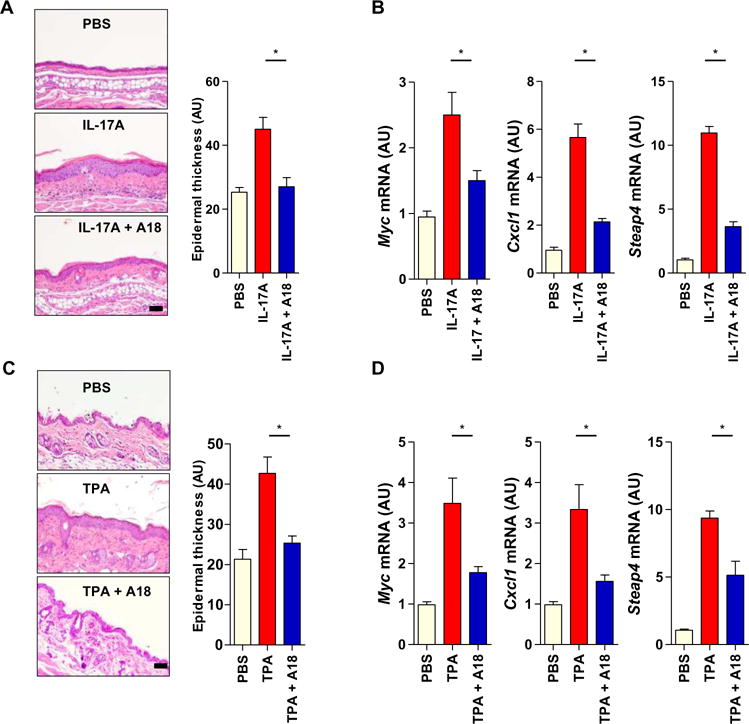

A18 inhibits IL-17A–dependent skin hyperplasia in mice

Secukinumab [an anti–IL-17A monoclonal antibody (mAb)] was approved by the FDA for the treatment of psoriasis (18, 21, 25). Abnormal keratinocyte proliferation is an important hallmark of the pathogenesis of psoriasis, which is a well-defined IL-17A–dependent disease. To examine the effect of A18 on IL-17A–induced epidermal cell proliferation, we intradermally injected the ears of female WT C57BL/6 mice with PBS or with IL-17A alone or together with A18 for six consecutive days. After the injections, the mice treated with IL-17 alone exhibited IL-17A–dependent epidermal hyperplasia, whereas the mice treated with both IL-17 and A18 exhibited reduced hyperplasia (Fig. 3A). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis revealed that the abundances of Myc, Cxcl1, and Steap4 mRNAs in the ears of IL-17A–treated mice were increased compared to those in the ears of PBS-treated mice but were not substantially increased in the ears of mice treated with both IL-17 and A18 (Fig. 3B). We and others previously showed that IL-17A signaling is also required for skin hyperplasia induced by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA) (2). Here, we found that the TPA-induced epidermal thickness and expression of target genes were substantially reduced by A18 (Fig. 3, C and D). Together, these data suggest that IL-17A induces epidermal hyperplasia, which was inhibited by A18.

Fig. 3. A18 inhibits IL-17A–dependent skin hyperplasia in mice.

(A) Eight-week-old female C57BL/6J mice (n = 5 mice per group) were injected intradermally with PBS, IL-17A alone, or both IL-17A and A18. Left: Six days later, ear tissue was removed from the mice and subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining to assess ear thickness. Images are representative of three independent experiments. Right: Quantitative analysis of ear thickness in the indicated groups of mice. (B) Ear skin samples from the mice described in (A) were subjected to RT-PCR analysis of the relative abundances of Myc, Cxcl1, and Steap4 mRNAs. Error bars in (A) and (B) represent the SEM calculated from 15 mice from three independent experiments. (C) Eight-week-old female C57BL/6J mice (n = 6 mice per group) were treated on the dorsal skin with PBS, TPA alone, or both TPA and A18. TPA was applied to the mice on days 1 and 4, whereas A18 was applied daily. Left: On day 7, dorsal skin tissue was removed from the mice and subjected to H&E staining to assess epidermal thickness. Images are representative of three independent experiments. Right: Quantitative analysis of epidermal thickness in the indicated groups of mice. (D) Dorsal skin samples from the mice described in (C) were subjected to RT-PCR analysis of the relative abundances of Myc, Cxcl1, and Steap4 mRNAs. Error bars in (C) and (D) represent the SEM calculated from 18 mice from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05. Scale bars, 100 μm.

A18 inhibits TH17 cell–induced, but not TH1 cell– or TH2 cell–induced, inflammation in mice

A study showed that IL-17A–producing TH17 cells play a critical role in the development and pathogenesis of EAE, a mouse model of multiple sclerosis (14). EAE is markedly suppressed in mice lacking IL-17A or the IL-17RA and IL-17RC subunits. Therefore, TH17 cell–mediated EAE is a suitable animal disease model in which to test the efficacy and specificity of A18 on IL-17A bioactivity. We found that A18 substantially delayed the onset of EAE and attenuated disease severity in mice that received myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)–specific TH17 cells (fig. S3A); A18-treated mice exhibited diminished demyelination in the spinal cords and reduced expression of IL-17A target genes (fig. S3, B and C). However, A18 had no effect on the infiltration into the brains of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, or F4/80+ macrophages, whereas the recruitment of Ly6G+ neutrophils into the brains was substantially reduced in the A18-treated mice (fig. S3D). These results suggest that A18 suppresses TH17 cell–mediated EAE, which may partly be a result of attenuation of the IL-17A–dependent recruitment of neutrophils into the central nerve system (CNS).

A18 failed to block TH1 cell–induced EAE in mice (fig. S3E), which suggests that the effect of A18 on inflammation in the CNS is specific to TH17 cell–mediated disease. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells accumulate in the CNS during EAE development, reaching their greatest numbers during the recovery phase (29). The accumulation of these cells in the CNS may limit EAE severity by suppressing the proliferation of effector T cells. We found that A18 did not affect the numbers of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells in lymphoid organs (spleen and lymph nodes) or in the CNS during the recovery phase (day 20) (fig. S3F), suggesting that A18 did not act through Treg cells to alleviate EAE. To determine whether A18 treatment needed to be maintained during EAE, we examined EAE development after the cessation of treatment with A18 (on day 15 when the untreated group of mice exhibited maximal disease severity) (fig. S3G). Whereas the clinical score of the mice steadily increased after the withdrawal of A18, disease severity (in both the peak and remission stages) was substantially reduced as compared with that in mice that were never treated with A18. These data suggest that the administration of A18 only during the early stage has beneficial effects on overall disease development, although continuous administration of A18 is required to effectively suppress TH17 cell–mediated EAE.

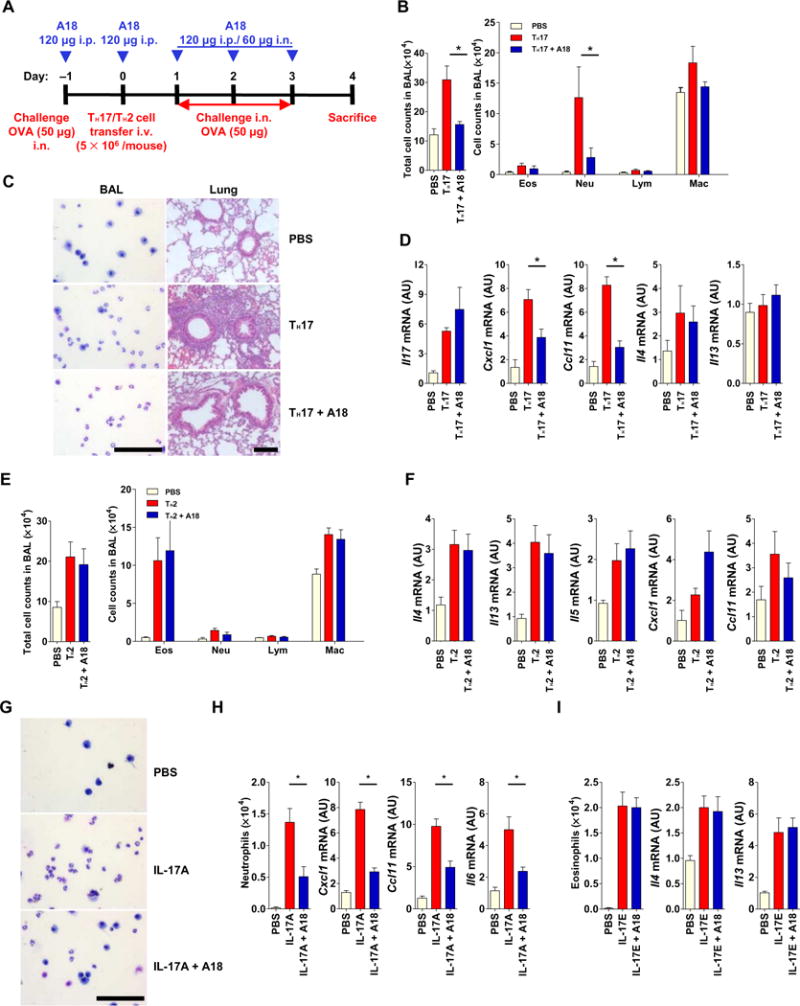

To test the efficacy and specificity of A18 on TH17 cell– versus TH2 cell–mediated inflammation, we performed experiments in which we adoptively transferred TH17 or TH2 cells specific for an ovalbumin-derived peptide (OVA-specific cells), which elicit neutrophilic and eosinophilic airway inflammation, respectively, to recipient mice (Fig. 4A). We found that A18 substantially reduced TH17 cell–induced neutrophilia (Fig. 4, B and C) and inflammatory gene expression in the lungs (Fig. 4D). Conversely, A18 had no effect on TH2 cell–induced eosinophilia (Fig. 4E) or on the expression of genes encoding TH2 cell–type cytokines in the lungs (Fig. 4F). Consistent with these findings, A18 substantially inhibited IL-17A–induced pulmonary neutrophilia and the expression of IL-17A target genes (Cxcl1, Il6, and Ccl11) (Fig. 4, G and H), whereas A18 did not inhibit IL-17E–induced pulmonary eosinophilia or TH2 cell–associated gene expression (Fig. 4I). These results suggest that A18 specifically inhibits airway inflammation induced by TH17 cells but not that induced by TH2 cells.

Fig. 4. A18 inhibits TH17 cell–induced, but not TH2 cell–induced, airway inflammation in mice.

(A) OVA323–339-specific TH17 or TH2 cells were adoptively transferred (with or without A18) into 8-week-old female C57BL/6J mice (n = 5 mice per treatment group), which were treated as indicated to induce antigen-specific airway inflammation. Each TH17 cell– or TH2 cell–based experiment was performed three times with its own PBS control. Data are means ± SEM of three independent experiments. (B to D) When the mice described in (A) that received the TH17 cells were sacrificed, the total and indicated immune cell counts in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) were quantified (B), representative BAL cells were prepared by cytospin and lung tissue was subjected to H&E staining (C), and the relative abundances of the indicated mRNAs isolated from lung tissue were determined by RT-PCR analysis (D). (E and F) When the mice described in (A) that received the TH2 cells were sacrificed, the total and indicated immune cell counts in the BAL were quantified (E). In addition, the relative abundances of the indicated mRNAs were determined by RT-PCR analysis (F). (G to I) IL-17A–induced neutrophilic and IL-17E–induced eosinophilic airway inflammation in the 8-week-old BALB/cJ mice (n = 5 mice per treatment group) with or without A18. (G) Representative BAL cytospin preparations from the mice were analyzed. (H and I) The numbers of neutrophils and eosinophils were counted, and the relative abundances of the indicated mRNAs isolated from lung tissue were determined by RT-PCR analysis. Each IL-17A– or IL-17E–based experiment was performed three times with its own PBS control. Data are means ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05. Scale bars, 100 μm. i.p., intraperitoneally; i.v., intravenously; i.n., intranasally.

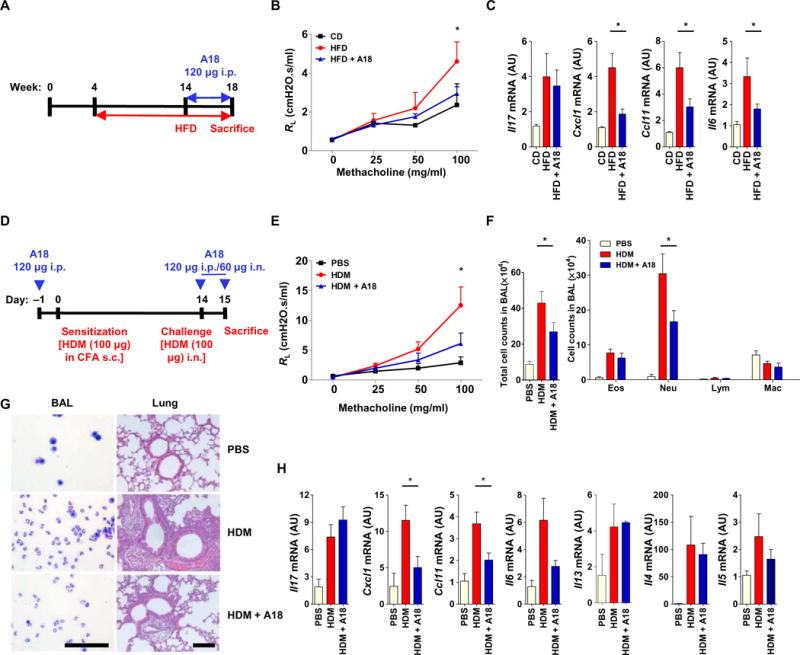

A18 attenuates airway inflammation in mouse models of steroid-resistant and severe asthma

Previous studies showed that obesity is a major risk factor for the development of asthma and contributes to disease severity (30–33). Obese individuals with asthma respond poorly to typical asthma medications, including corticosteroids (33). A study found that IL-17A signaling provides a critical link between obesity and asthma (34). Mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) develop AHR that is IL-17A–dependent. These data suggest that the IL-17A pathway is an important target for the treatment of steroid-resistant, obesity-associated asthma. In our experiments, we found HFD-induced TH17 cells in the periphery, as well as in the lung, whereas HFD-induced AHR was substantially reduced in IL-17RC−/− mice compared to in WT mice (fig. S4, A to C). Because HFD-induced AHR is an IL-17A–mediated disease model, we investigated whether A18 could attenuate disease. Male WT C57BL/6 mice were fed a chow diet (CD) or a HFD for 14 weeks starting at 4 weeks of age and were then treated with or without A18 for the last 4 weeks of the experiment (Fig. 5A). A18 substantially attenuated HFD-induced AHR and the extent of inflammatory gene expression (Fig. 5, B and C), which is suggestive of a potential therapeutic role for A18 in the treatment of IL-17A–dependent asthma, including obesity-associated, steroid-resistant asthma.

Fig. 5. A18 attenuates airway inflammation in mouse models of steroid-resistant and severe asthma.

(A) Four-week-old male C57BL/6 mice (n = 5 mice per group) were fed a normal CD or a HFD for 14 weeks, and during the last 4 weeks, they were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or A18. (B) Before the mice were sacrificed, lung resistance (RL) was determined. (C) At the time of sacrifice, lung tissue was subjected to RT-PCR analysis of the abundances of the indicated mRNAs. Data are means ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 when comparing HFD mice with A18-treated HFD mice. (D) C57BL/6 mice (n = 6 mice per group) were sensitized and challenged with HDM in the presence or absence of A18 as indicated. (E) Before the mice were sacrificed, lung resistance (RL) was determined. (F) Total and individual immune cell counts in the BAL of the indicated mice were determined. (G) BAL cytospins were prepared, and lung tissue was subjected to H&E staining. Scale bars, 100 μm. (H) The relative abundances of the indicated mRNAs isolated from lung tissue were determined by RT-PCR analysis. Data are means ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 when comparing HDM mice with A18-treated HDM mice.

House dust mite (HDM), a natural allergen to which asthmatics are often sensitized, induces neutrophilic airway inflammation, which is often associated with severe asthma (35). Consistent with these findings, we showed that IL-17RC−/− mice had substantially reduced neutrophilic airway inflammation in a high-dose HDM–induced model of severe asthma (fig. S5, A to D). We then evaluated the ability of A18 to alleviate neutrophilia and AHR in this model of IL-17A–dependent severe asthma (Fig. 5D). HDM-induced neutrophilia, AHR, and inflammatory gene expression in the lungs were substantially reduced in A18-treated mice compared to those in control mice (Fig. 5, E to H). Together, the results from both the HFD and HDM experiments suggest that A18 may have a potential therapeutic role in the treatment of IL-17A–mediated steroid-resistant and severe asthma.

Certain hydroxyl groups of A18 are critical for its ability to inhibit IL-17A

To further develop A18 into a drug candidate, it is important to define the critical elements and functional groups that are responsible for its inhibitory activities. This information will provide guidance for the structural optimization of A18 by medical chemistry in drug development. On the basis of computational docking of A18 to the binding pocket of IL-17RA, all five of the hydroxyl (−OH) groups of A18 are involved in hydrogen bond formation with IL-17RA (Fig. 1C and fig. S6A). Using existing compounds, we tested the importance of some of the hydroxyl groups in the inhibitory effect of A18. We found that the B3′-OH was critical for the inhibitory activity of A18 in IL-17A/IL-17RA binding assays, because removal or modification of B3′-OH, which generates pelargonidin or peonidin, respectively, substantially increased the IC50 values of the resulting compounds (>100 μM) (fig. S6B). This finding is consistent with our docking model in which B3′-OH makes a potential hydrogen bond with Gln124 of IL-17RA.

We also tested whether removal or modification of the C3–OH, which generates luteolinidin or cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, affected the inhibitory activity of A18 (fig. S6C). We found that the IC50 values of both compounds in the in vitro ligand-receptor binding inhibition assay (see Materials and Methods) were noticeably increased (from 1.68 to 6.75 and 6.88 μM, respectively). This suggests that the C3–OH also plays a role in the binding of A18 to IL-17RA, which is consistent with our docking model in which C3–OH makes a potential hydrogen bond with Asp262, as well as with the finding that the D262A mutation decreased the binding of IL-17RA to A18 (Fig. 1K). Note that another member of the anthocyanidins A10 (also known as delphinidin), which has an additional hydroxyl group at B5′ as compared with A18, has a comparable GlideScore (which refers to the theoretical or computational binding energy: the smaller the score, the more easily the binding event occurs) and a slightly improved IC50 value compared to that of A18 (fig. S6D). To test the importance of −OH at A5, we synthesized A18Δ5OH (fig. S6E). The removal of the hydroxyl group at A5 resulted in a compound that retained some inhibitory activity in the in vitro inhibition assays (IC50, >30 μM), but that was much less potent than A18, demonstrating the importance of A5-OH for the activity of A18. Consistent with this finding, the A5-OH group makes a potential hydrogen bond with the backbone of Leu264 in our docking model.

To test the importance of ring C, we synthesized A18-C5 (fig. S6F), in which the six-membered ring C was replaced with a five-membered ring. A18C5 showed very little activity in an in vitro inhibition assay (IC50, >100 μM) (fig. S6F). These results suggest that the geometry of ring C in A18 is important for its activity. Together, these data suggest that the scaffold represented by A18 with the regio-presentation of the four hydroxyl groups on rings A and B provides strong hydrogen bonding interactions with the extracellular domain of IL-17RA. These hydroxyl groups (R1 to R4) may be replaced with amines, amides, and cyanides and with other hydrogen bond donor groups to improve the potency of A18 and reduce the metabolism of the hydroxyl groups. Replacement of the R5 groups in the basic skeleton of A18 with certain nonhydroxyl substituents should have minimal effect on the inhibitory activities of the derived compounds. One may replace R5 with F, Cl, or glycoside to improve stability. This basic skeleton of A18 could be used as the prototype for developing A18-derived, small-molecule drug candidates for clinical application (fig. S6G).

DISCUSSION

We report the discovery of the small-molecule compound A18 (cyanidin), a member of the anthocyanin subfamily of the flavonoid super-family, as an effective inhibitor of the binding of IL-17A to IL-17RA, resulting in attenuation of IL-17A signaling and associated diseases. Although monoclonal neutralizing antibodies developed as candidate drugs to target IL-17A or IL-17RA and thus inhibit IL-17A signaling have shown promising results in clinical trials, they have high production costs and limited administration routes (they can be delivered only through intravenous administration). Therefore, our small-molecule, A18-derived drugs could provide cost-effective alternatives for the treatment of IL-17A–dependent inflammatory diseases and cancer.

Cyanidin is a particular type of anthocyanidin (the sugar-free counterparts of anthocyanins), which is present as a pigment in many red berries and other fruits, such as apples and plums, with the highest concentrations found in the skin of the fruit. Cyanidin and its related compounds have various beneficial effects, including antiatherosclerotic, anti-inflammatory, antithrombogenic, antitumor, antiosteoporotic, and antiviral effects in animals and humans (36–40). However, the precise mechanism of action of cyanidin is poorly understood. Here, we elucidated a previously uncharacterized molecular mechanism for cyanidin and its related structures based on their ability to inhibit IL-17A/IL-17RA binding, which is supported by computational modeling, in vitro binding measurements, cell-based assays, and in vivo studies. This inhibitory effect of cyanidin on the IL-17A/IL-17RA interaction helps to explain its anti-inflammatory bioactivities in vivo, because IL-17A is involved in a wide range of chronic inflammatory diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, EAE, allergen-induced pulmonary inflammation, psoriasis, and cancer. The fact that A18 specifically inhibited inflammation induced by IL-17A from TH17 cells, but not that induced by TH1 or TH2 cells, supports the hypothesis that the inhibitory mechanism of cyanidin is due to its ability to block the binding of IL-17A to IL-17RA. Accumulating evidence suggests that aberrant IL-17A production is a key determinant of severe and steroid-resistant forms of asthma (11, 41–45). We found that A18 attenuated airway inflammation and AHR in mouse models of steroid-resistant and severe asthma. Our studies suggest that cyanidin-derived small molecules could be developed into a new class of drugs to treat severe asthmatics and patients with other IL-17A–dependent autoimmune diseases and cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

B6.OT-II T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic mice and WT C57BL/6 or BALB/cJ mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories. IL-17RC–deficient mice were obtained from W. Ouyang (Genentech, San Francisco, CA) and were described previously (2). All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Cleveland Clinic.

Reagents and cell culture

Purified recombinant human IL-17A, human IL-17E (IL-25), human IL-17C, human IL-17RA–Fc [amino acid residues 33 to 322 of the extracellular domain of IL-17RA fused to the Fc region of human immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) at the C terminus], human IL-17RB–Fc (residues 18 to 289 of the extracellular domain of IL-17RB fused to the Fc region of human IgG1 at the C terminus), and human IL-17RE–Fc (residues 155 to 454 of the extracellular domain of IL-17RE fused to the Fc region of human IgG1 at the C terminus) proteins and HRP-conjugated IgG Fc secondary antibody were purchased from Sino Biological Inc. Human; and mouse IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-17A/F heterodimer, IL-17E, IL-23, and IL-4, ELISA kits to detect human GROα, IL-6, and IL-8, as well as mouse KC, IL-6, and MIP-2, and the human IL-17 Biotinylated Fluorokine Flow Cytometry Kit were purchased from R&D Systems. Mouse transforming growth factor–β (TGF-β) and IL-6 were obtained from PeproTech. Anti–IL-4 mAb (clone 11B11), anti–interferon-γ (IFN-γ) mAb (clone XMG1.2), and fluorescently conjugated antibodies against CD4 (clone GK1.5), CD8 (clone 53-6.7), CD45 (clone 30-F11), and Ly6G (clone 1A8) were purchased from BD Biosciences. Antibody against the FLAG tag (M2) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Anti-human Act1 antibodies were obtained from eBioscience. The Mouse Treg Flow Kit was obtained from BioLegend. Antibody against F4/80 (clone A3-1) was obtained from Serotec. The Bac-to-Bac Baculovirus Expression System and Sf9 insect cells were purchased from Life Technologies. Superdex 200 10/300 GL was obtained from GE Healthcare. HEK 293 cells stably expressing IL-17RA (IL-17RA–293), HeLa cells, A549 cells, HT-29 cells, MEFs, and MEFs stably expressing IL-17RB (IL-17RB–MEF) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Human primary smooth muscle cells were provided by S. Comair (Department of Pathobiology, Cleveland Clinic). Mouse primary smooth muscle cells and kidney epithelial cells were isolated and cultured as described previously (8, 46). Lack of Mycoplasma was confirmed for all cell cultures using the Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit (Sigma, MP0035-1KT). All cell lines were obtained from and authenticated by the American Type Culture Collection.

Compounds

Cyanidin chloride (A18; CAS 528-58-5), peonidin (CAS 134-01-0), and cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (CAS 7084-24-4) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Pelargonidin (CAS 134-04-3) and delphinidin (CAS 528-53-0) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Luteolinidin (CAS 1154-78-5) was obtained from INDOFINE Chemical Company. A18Δ5OH and A18-C5 were synthesized by Bellen Chemistry and WuXi AppTec, respectively.

High-throughput virtual screening

Virtual screening was performed with Maestro 9.6 software (Schrödinger Release 2013–3, Schrödinger LLC.) and the high-performance computing (HPC) cluster server at the Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) with the following procedures. In terms of ligand preparation, the compound library for screening, which contains 89,253 compounds in SDF format, was downloaded from the online resources NCI Plated 2007 and NCI Diversity 3 (http://zinc.docking.org/catalogs/ncip). Before docking, all compounds were preprocessed with the LigPrep module in Maestro. Each compound was desalted, and tautomers of the possible ionization states in the pH range of 5.0 to 9.0 were generated by Epik mode in the force field of OPLS_2005. In terms of protein preparation, the structure of IL-17RA was derived from PDB (PDB code 4HSA or 3JVF). Before docking, the protein was processed and refined with the Protein Preparation module in Maestro. In general, hydrogen atoms were added, water molecules were removed, H-bond assignment was optimized, and restrained minimization was conducted with the force field of OPLS_2005. To generate the docking grid, we used the segment (amino acid residues 35 to 46) derived from IL-17A or the segment (residues 36 to 47) from IL-17F, which forms a complex with IL-17RA, to define the center of the docking pocket and set the scaling factor and the partial charge cutoff of the van der Waals radii at 1.0 and 0.25, respectively. This step was performed with the Receptor Grid Generation module in Maestro. In terms of glide docking, initially, all of the prepared compounds were docked into the defined binding pocket of IL-17RA using the high-throughput virtual screening mode and ranked by the docking score. The two sets of the top 2500 compounds (from 4HSA and 3JVF respectively) were then both redocked into IL-17RA separately with the SP (standard precision) and XP (extra precision) modes, respectively. The compounds seen in both sets were selected and compared for their SP and XP docking scores, and their docking conformations were then carefully inspected by visual observation. Eventually, 64 potential compounds were purchased for bioassays. The docking simulations were conducted on the HPC cluster server at CWRU, and the docking conformation analysis was performed with PyMol.

Ligand-receptor binding inhibition assay

For binding assays with purified proteins, we coated ELISA plates with human IL-17A, IL-17E, or IL-17C (each at 2 μg/ml in PBS) to which we added human IL-17RA–Fc, human IL-17RB–Fc, or human IL-17RE–Fc (each at 150 ng/ml), respectively. The plates were then incubated for 1 hour, which was followed by incubation with goat HRP-conjugated anti-human IgG Fc secondary antibody in the presence or absence of A18 for 1 hour. ELISAs were performed with tetramethylbenzidine substrate. For binding assays with live cells, IL-17RA–293 cells or HeLa cells were detached from culture plates with 0.5 mM EDTA and washed with PBS. The cells were then incubated with PBS alone or with biotinylated human IL-17A in the presence of PBS (as a negative control), A18 (10 μM), or anti-human IL-17A antibody (as a positive control). The cells were then subjected to avidin-fluorescein staining with the human IL-17A Biotinylated Fluorokine Flow Cytometry Kit. The extent of IL-17A binding to the cells was then examined by flow cytometry.

Protein expression and purification

Human IL-17RA WT and D262 mutant proteins were generated with the Bac-to-Bac Baculovirus Expression System (Life Technologies) as previously described (27). High-titer recombinant baculovirus was used to infect Sf9 insect cells at a density of 2 × 106 viable cells/ml. The cells were cultured at 28°C and harvested 72 hours after infection. The soluble, secreted, hexahistidine-tagged proteins were purified from the culture medium with a nickel-affinity chromatography column and then with Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare).

Binding studies by microscale thermophoresis and fluorescence measurement

The interactions of WT or mutant IL-17RA proteins with A18 were investigated with a NanoTemper Monolith NT.115 instrument, which was used to measure changes in the fluorescence of labeled IL-17RA that were caused by A18. Purified IL-17RA protein was labeled with the RED fluorescent dye NT-647-NHS (NanoTemper Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A18 was mixed with the labeled IL-17RA (22 nM) at different concentrations in 50 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.05% Tween 20, and 2.5% DMSO. The extent of the interaction between the IL-17RA protein (WT or mutant) and IL-17A was determined by microscale thermophoresis (MST). Un-labeled IL-17A was prepared in MST buffer [50 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 % Pluronic F-127] and mixed with the labeled IL-17RA (22 nM) at different concentrations. The samples were incubated at room temperature for 10 min and loaded into MST premium glass capillary tubes. Data were acquired at room temperature using 20% light-emitting diode power and 20% MST level. At least two independent experiments were performed. Data analysis was performed with MO.Affinity Analysis software (NanoTemper Technologies).

SPR measurement

The extent of binding of A18 to IL-17RA was measured on a Biacore T100 instrument. Purified IL-17RA was immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip with an amine coupling kit (GE Healthcare). Solutions of different concentrations of A18 in PBSPP+ buffer [20 mM sodium phosphate, 2.7 mM KCl, 137 mM NaCl, and 0.05% P20 (pH 7.4)] were allowed to flow over the chip. The chip was regenerated with 2 M GnHCl. Kd values were determined with BIAevaluation software.

Differential cell counting and histology staining

BAL and peritoneal lavage cell counts were determined by cytospin slide preparation after a Diff-Quik Giemsa stain. For histological analysis, mouse lung tissue was fixed in 10% buffered formalin and then subjected to H&E staining.

Peritoneal administration of IL-17A

Eight-week-old female WT BALB/cJ mice were subjected to intraperitoneal injection with PBS or with 0.5 μg of IL-17A alone or in the presence of A18 (120 μg per mouse). Six hours later, the peritoneal cavities of the injected mice were lavaged with 5 ml of ice-cold PBS. Peritoneal neutrophils were counted and quantified by differential cell counting.

Intranasal injection of IL-17A and IL-17E

Eight-week-old female WT BALB/cJ mice were subjected to intranasal injection with PBS or with 0.5 μg of IL-17A or IL-17E in the presence or absence of A18 (60 μg per mouse) in PBS. BAL and lung tissues were collected at 4 hours (for the IL-17A–treated group) or 24 hours (for the IL-17E–treated group) after injection for BAL cell counting and RT-PCR analysis, respectively.

Intradermal injection of IL-17A

The ears of 8-week-old female WT C57BL/6 were injected intradermally with 20 μl of PBS alone or with PBS containing 0.5 μg of recombinant mouse IL-17A in the presence or absence of A18 (60 μg per mouse). A18 (120 μg per mouse) was also administered (intraperitoneally) daily. Six days after injection, the ears were fixed in 10% formalin and stained with H&E. Epidermal thickness was quantified by ImageJ software.

TPA-induced skin hyperplasia

The dorsal skin of 8-week-old female WT C57BL/6 mice was treated with 12.5 μg of TPA (Sigma-Aldrich, P8139) in 200 μl of acetone in the presence or absence of A18 (60 μg per mouse) on days 1 and 4. A18 (120 μg per mouse) was also administered (intraperitoneally) daily. On day 7, the dorsal skin were fixed in 10% formalin and stained with H&E. Epidermal thickness was quantified by ImageJ software.

Adoptive transfer models for antigen-induced airway inflammation

The methods for the TH17 cell– and TH2 cell–based adoptive transfer experiments were adapted from published studies (47, 48). Naïve CD4+CD44− T cells were sorted from the spleens and lymph nodes of OT-II TCR transgenic mice. To generate OVA-specific TH17 cells, we cultured naïve CD4+ T cells with irradiated splenic feeder cells in the presence of OVA323–339 peptide (5 μg/ml), TGF-β (5 ng/ml), IL-6 (20 ng/ml), IL-23 (10 ng/ml), anti–IL-4 mAb (20 μg/ml), and anti–IFN-γ mAb (20 μg/ml). OVA323–339-specific TH2 cells were polarized with IL-4 (20 ng/ml) and anti–IFN-γ mAb (20 μg/ml). TH17 or TH2 cells were then transferred intravenously into female WT C57BL/6 mice (5 × 106 cells per mouse). The mice were challenged (intranasally) with OVA323–339 (50 μg/ml) 1 day before transfer and three consecutive days after transfer. BAL cell counting and tissue collection were performed 24 hours after the last challenge. For A18 treatment, mice were injected (intraperitoneally) with A18 (120 μg per mouse) on each challenge day.

HFD intervention

Starting at 4 weeks of age, male WT C57BL/6 mice were fed with a CD (10 kcal % fat) or a HFD (60 kcal % fat) for 14 weeks. The HFD + A18 group of mice were injected (intraperitoneally) with A18 (120 μg per mouse) daily for the final 4 weeks before being subjected to AHR measurement. Both the CD (D12450B) and HFD (D12492) were obtained from Research Diets Inc.

Measurement of AHR

AHR was measured in mice in response to increasing doses of inhaled methacholine by flexiVent as described previously (49). Each mouse was aerosolized with methacholine in saline at doses of 0, 25, 50, and 100 mg/ml. Lung resistance was determined with the forced oscillation technique by flexiVent 5.2 software.

HDM-induced asthma

Eight-week-old female WT C57BL/6 mice were sensitized subcutaneously with HDM (100 μg per mouse; Dermatophagoides farina, Greer Laboratories) in complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) on day 0 and subsequently challenged (intranasally) with HDM (100 μg per mouse) on day 14. AHR measurement, BAL cell counting, and tissue collection were performed 24 hours after the last HDM challenge. The HDM + A18 group of mice were injected (intraperitoneally) with A18 (120 μg per mouse) on days 13 and 14 and were also administered with A18 (60 μg per mouse) (intranasally) 1 hour before challenge.

Adoptive transfer of TH1 or TH17 cells to induce EAE

MOG35–55-specific TH1 or TH17 cells were polarized as described previously (12, 13). To induce TH1 cell– or TH17 cell–mediated EAE, we injected (intraperitoneally) 10-week-old female WT C57BL/6J mice with polarized MOG 35–55-specific TH1 or TH17 cells (5 × 107 cells per mouse) with or without A18 (60 μg per mouse) after sublethal irradiation (500 rads). A18 (120 μg per mouse) was continuously administered (intraperitoneally) to the treated mice every other day after the transfer of the TH1 or TH17 cells. At the peak of disease severity, the mice were sacrificed and perfused with PBS. The spinal cords were fixed in 10% formalin, which was followed by staining with either H&E or Luxol fast blue to evaluate inflammation and demyelination, respectively. The brains were removed and homogenized in ice-cold tissue grinders and filtered through a 100-mm cell strainer, and the cells were collected by centrifugation at 400g for 5 min at 4°C. The cells were resuspended in 30% Percoll and centrifuged onto a 70% Percoll cushion in 15-ml tubes at 800g for 30 min. Those cells at the 30 to 70% interface were collected and subjected to flow cytometric analysis after staining with the appropriate antibodies. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells were stained with the Mouse Treg Flow Kit.

RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted by TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All gene expression results (mRNA abundances) were expressed as arbitrary units relative to abundance of Actb mRNA. The primers used are as follows: Myc: forward, 5′-ATGCCCCTCAACGTGAACTTC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CGCAACATAGGATGGAGAGCA-3′; Cxcl1: forward, 5′-TAGGGTGAGGACATGTGTGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-AAATGTCCAAGGGAAGCGT-3′; Steap4: forward, 5′-GGGAAGTCACTGGGATTGAAAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-CCGAATAGCTCAGGACCTCTG-3′; Ccl11: forward, 5′-GAATCACCAACAACAGATGCAC-3′ and reverse, 5′-ATCCTGGACCCACTTCTTCTT-3′; Il4: forward, 5′-GGTCTCAACCCCCAGCTAGT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCCGATGATCTCTCTCAAGTGAT-3′; Il13: forward, 5′-CCTGGCTCTTGCTTGCCTT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGTCTTGTGTGATGTTGCTCA-3′; Il5: forward, 5′-CTCTGTTGACAAGCAATGAGACG-3′ and reverse, 5′-TCTTCAGTATGTCTAGCCCCTG-3′; Il6: forward, 5′-GGACCAAGACCATCCAATTC-3′ and reverse, 5′-ACCACAGTGAGGAATGTCCA-3′; Il17: forward, 5′-TTTAACTCCCTTGGCGCAAAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTTTCCCTCCGCATTGACAC-3′; and Actb: forward, 5′-GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG-3′ and reverse, 5′-CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT-3′.

Statistical analysis

A nonparametric Mann-Whitney test (performed with GraphPad Prism software) was used for all comparisons unless otherwise noted in the figure legends. All results are shown as means ± SEM. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. A18 binds directly to IL-17RA.

Fig. S2. A18 specifically inhibits IL-17A–induced gene expression.

Fig. S3. A18 alleviates TH17 cell–mediated, but not TH1 cell–mediated, EAE in mice.

Fig. S4. HFD-induced asthma is attenuated in IL-17RC–deficient mice.

Fig. S5. HDM- and CFA-induced asthma is alleviated in IL-17RC–deficient mice.

Fig. S6. Analysis of the C6–C3–C6 flavonoid skeleton and of the hydroxyl groups of A18 that are critical to inhibit IL-17A signaling.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Zheng and H. Jiang at the Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica for help in the initial stage of the virtual screening. We also thank G. Cheng and L. Raple for help with AHR measurements with flexiVent. We are grateful to Y. Chen of CWRU for help with the Biacore assay.

Funding: This study was supported by the NIH (grants R01NS071996, P01 CA062220-21 project 3, P01 HL103453 project 2, and 1UH54HL119810-01 to X.L. and RO1HL58758 to J.Q.), the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (grant RG5130A2/1 to X.L.), and the Cleveland Clinic Innovations. This work made use of the High Performance Computing Resource in the Core Facility for Advanced Research Computing at CWRU.

Footnotes

Author contributions: C.L., X.L., and J.Q. designed all of the experiments. L.Z. and J.Q. performed computational virtual screening and docking analysis. K.F. expressed and purified the recombinant IL-17RA proteins and performed MST and fluorescence measurements of the binding of A18 and IL-17A to IL-17RA. C.L. and L.Q. performed all of the biochemical and cell-based inhibition assays. C.L., S.O., and C.-j.Z. performed mouse experiments involving injection of IL-17A or IL-17E, TH17 cell– or TH2 cell–induced airway inflammation, and HFD- or HDM-induced asthma. X.C., C.G., and C.L. conducted the IL-17A– and TPA-induced skin hyperplasia experiments. M.A. supervised all of the asthma studies. C.W., B.M., S.O., and C.L. performed the EAE experiments. C.L. and S.R. performed the structure-activity relationship analysis of A18. X.L., C.L., and J.Q. wrote the paper with input from all co-authors. X.L. and J.Q. supervised all aspects of the study.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencesignaling.org/cgi/content/full/10/467/eaaf8823/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Miossec P, Kolls JK. Targeting IL-17 and TH17 cells in chronic inflammation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:763–776. doi: 10.1038/nrd3794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu L, Chen X, Zhao J, Martin B, Zepp JA, Ko JS, Gu C, Cai G, Ouyang W, Sen G, Stark GR, Su B, Vines CM, Tournier C, Hamilton TA, Vidimos A, Gastman B, Liu C, Li X. A novel IL-17 signaling pathway through the TRAF4-ERK5 axis for keratinocyte proliferation and tumorigenesis. J Exp Med. 2015;10:1571–1587. doi: 10.1084/jem.20150204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed M, Gaffen SL. IL-17 in obesity and adipogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:449–453. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ye P, Rodriguez FH, Kanaly S, Stocking KL, Schurr J, Schwarzenberger P, Oliver P, Huang W, Zhang P, Zhang J, Shellito JE, Bagby GJ, Nelson S, Charrier K, Peschon JJ, Kolls JK. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J Exp Med. 2001;194:519–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trinchieri G. Cancer and inflammation: An old intuition with rapidly evolving new concepts. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:677–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright JF, Bennett F, Li B, Brooks J, Luxenberg DP, Whitters MJ, Tomkinson KN, Fitz LJ, Wolfman NM, Collins M, Dunussi-Joannopoulos K, Chatterjee-Kishore M, Carreno BM. The human IL-17F/IL-17A heterodimeric cytokine signals through the IL-17RA/IL-17RC receptor complex. J Immunol. 2008;181:2799–2805. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alcorn JF, Crowe CR, Kolls JK. TH17 cells in asthma and COPD. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:495–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulek K, Liu C, Swaidani S, Wang L, Page RC, Gulen MF, Herjan T, Abbadi A, Qian W, Sun D, Lauer M, Hascall V, Misra S, Chance MR, Aronica M, Hamilton T, Li X. The inducible kinase IKKi is required for IL-17-dependent signaling associated with neutrophilia and pulmonary inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:844–852. doi: 10.1038/ni.2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallimore AM, Godkin A. Epithelial barriers, microbiota, and colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:282–284. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1212341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milner JD. IL-17 producing cells in host defense and atopy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23:784–788. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silverpil E, Lindén A. IL-17 in human asthma. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2012;6:173–186. doi: 10.1586/ers.12.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang Z, Altuntas CZ, Gulen MF, Liu C, Giltiay N, Qin H, Liu L, Qian W, Ransohoff RM, Bergmann C, Stohlman S, Tuohy VK, Li X. Astrocyte-restricted ablation of interleukin-17-induced Act1-mediated signaling ameliorates autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Immunity. 2010;32:414–425. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang Z, Wang C, Zepp J, Wu L, Sun K, Zhao J, Chandrasekharan U, DiCorleto PE, Trapp BD, Ransohoff RM, Li X. Act1 mediates IL-17–induced EAE pathogenesis selectively in NG2+ glial cells. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1401–1408. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu C, Wu L, Li X. IL-17 family: Cytokines, receptors and signaling. Cytokine. 2013;64:477–485. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu L, Zepp J, Li X. Function of Act1 in IL-17 family signaling and autoimmunity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;946:223–235. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0106-3_13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zepp J, Wu L, Li X. IL-17 receptor signaling and T helper 17-mediated autoimmune demyelinating disease. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zarogoulidis P, Katsikogianni F, Tsiouda T, Sakkas A, Katsikogiannis N, Zarogoulidis K. Interleukin-8 and interleukin-17 for cancer. Cancer Invest. 2014;32:197–205. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2014.898156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown G, Malakouti M, Wang E, Koo JY, Levin E. Anti-IL-17 phase II data for psoriasis: A review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:32–36. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2013.878448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baeten D, Baraliakos X, Braun J, Sieper J, Emery P, van der Heijde D, McInnes I, van Laar JM, Landewé R, Wordsworth P, Wollenhaupt J, Kellner H, Paramarta J, Wei J, Brachat A, Bek S, Laurent D, Li Y, Wang YA, Bertolino AP, Gsteiger S, Wright AM, Hueber W. Anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody secukinumab in treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:1705–1713. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiricozzi A. Pathogenic role of IL-17 in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105(suppl 1):9–20. doi: 10.1016/S0001-7310(14)70014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiricozzi A, Krueger JG. IL-17 targeted therapies for psoriasis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2013;22:993–1005. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2013.806483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elain G, Jeanneau K, Rutkowska A, Mir AK, Dev KK. The selective anti-IL17A monoclonal antibody secukinumab (AIN457) attenuates IL17A-induced levels of IL6 in human astrocytes. Glia. 2014;62:725–735. doi: 10.1002/glia.22637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hueber W, Sands BE, Lewitzky S, Vandemeulebroecke M, Reinisch W, Higgins PD, Wehkamp J, Feagan BG, Yao MD, Karczewski M, Karczewski J, Pezous N, Bek S, Bruin G, Mellgard B, Berger C, Londei M, Bertolino AP, Tougas G, Travis SP. Secukinumab, a human anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody, for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: Unexpected results of a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Gut. 2011;61:1693–1700. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McInnes IB, Sieper J, Braun J, Emery P, van der Heijde D, Isaacs JD, Dahmen G, Wollenhaupt J, Schulze-Koops H, Kogan J, Ma S, Schumacher MM, Bertolino AP, Hueber W, Tak PP. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab, a fully human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriatic arthritis: A 24-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II proof-of-concept trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;73:349–356. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reichert JM. Antibodies to watch in 2014. mAbs. 2014;6:5–14. doi: 10.4161/mabs.27333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs from 1981 to 2014. J Nat Prod. 2016;79:629–661. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu S, Song X, Chrunyk BA, Shanker S, Hoth LR, Marr ES, Griffor MC. Crystal structures of interleukin 17A and its complex with IL-17 receptor A. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1888. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ely LK, Fischer S, Garcia KC. Structural basis of receptor sharing by interleukin 17 cytokines. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1245–1251. doi: 10.1038/ni.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGeachy MJ, Stephens LA, Anderton SM. Natural recovery and protection from autoimmune encephalomyelitis: Contribution of CD4+CD25+ regulatory cells within the central nervous system. J Immunol. 2005;175:3025–3032. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porsbjerg C, Rasmussen L, Nolte H, Backer V. Association of airway hyperresponsiveness with reduced quality of life in patients with moderate to severe asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;98:44–50. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60858-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Julia V, Macia L, Dombrowicz D. The impact of diet on asthma and allergic diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:308–322. doi: 10.1038/nri3830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forno E, Lescher R, Strunk R, Weiss S, Fuhlbrigge A, Celedon JC, Childhood Asthma Management Program Research Group Decreased response to inhaled steroids in overweight and obese asthmatic children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:741–749. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paggiaro P, Bacci E, Dente F, Vagaggini B. Poor response to inhaled corticosteroids in obese, asthmatic patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;108:217–218. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim HY, Lee HJ, Chang YJ, Pichavant M, Shore SA, Fitzgerald KA, Iwakura Y, Israel E, Bolger K, Faul J, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Interleukin-17–producing innate lymphoid cells and the NLRP3 inflammasome facilitate obesity-associated airway hyperreactivity. Nat Med. 2014;20:54–61. doi: 10.1038/nm.3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chesné J, Braza F, Chadeuf G, Mahay G, Cheminant MA, Loy J, Brouard S, Sauzeau V, Loirand G, Magnan A. Prime role of IL-17A in neutrophilia and airway smooth muscle contraction in a house dust mite-induced allergic asthma model. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:1643–1643. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.González R, Ballester I, López-Posadas R, Suarez MD, Zarzuelo A, Martínez-Augustin O, Medina F Sánchez de. Effects of flavonoids and other polyphenols on inflammation. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2011;51:331–362. doi: 10.1080/10408390903584094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nijveldt RJ, van Nood E, van Hoorn DE, Boelens PG, van Norren K, van Leeuwen PA. Flavonoids: A review of probable mechanisms of action and potential applications. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:418–425. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Afaq F, Syed DN, Malik A, Hadi N, Sarfaraz S, Kweon MH, Khan N, Zaid MA, Mukhtar H. Delphinidin, an anthocyanidin in pigmented fruits and vegetables, protects human HaCaT keratinocytes and mouse skin against UVB-mediated oxidative stress and apoptosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:222–232. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ding M, Feng R, Wang SY, Bowman L, Lu Y, Qian Y, Castranova V, Jiang BH, Shi X. Cyanidin-3-glucoside, a natural product derived from blackberry, exhibits chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic activity. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17359–17368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600861200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang SY, Seeram NP, Nair MG, Bourquin LD. Tart cherry anthocyanins inhibit tumor development in ApcMin mice and reduce proliferation of human colon cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2003;194:13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park SJ, Lee YC. Interleukin-17 regulation: An attractive therapeutic approach for asthma. Respir Res. 2010;11:78. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang YH, Wills-Karp M. The potential role of interleukin-17 in severe asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:388–394. doi: 10.1007/s11882-011-0210-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gibeon D, Menzies-Gow AN. Targeting interleukins to treat severe asthma. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2012;6:423–439. doi: 10.1586/ers.12.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trevor JL, Deshane JS. Refractory asthma: Mechanisms, targets, and therapy. Allergy. 2014;69:817–827. doi: 10.1111/all.12412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Ramli W, Préfontaine D, Chouiali F, Martin JG, Olivenstein R, Lemiere C, Hamid Q. TH17-associated cytokines (IL-17A and IL-17F) in severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1185–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lauer ME, Cheng G, Swaidani S, Aronica MA, Weigel PH, Hascall VC. Tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6 (TSG-6) amplifies hyaluronan synthesis by airway smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:423–431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.389882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McKinley L, Alcorn JF, Peterson A, Dupont RB, Kapadia S, Logar A, Henry A, Irvin CG, Piganelli JD, Ray A, Kolls JK. TH17 cells mediate steroid-resistant airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:4089–4097. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang YH, Voo KS, Liu B, Chen CY, Uygungil B, Spoede W, Bernstein JA, Huston DP, Liu YJ. A novel subset of CD4+ TH2 memory/effector cells that produce inflammatory IL-17 cytokine and promote the exacerbation of chronic allergic asthma. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2479–2491. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swaidani S, Bulek K, Kang Z, Liu C, Lu Y, Yin W, Aronica M, Li X. The critical role of epithelial-derived Act1 in IL-17- and IL-25-mediated pulmonary inflammation. J Immunol. 2009;182:1631–1640. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang J, Zhang Y. Protein structure and function prediction using I-TASSER. Curr Protoc Bioinf. 2015;52:5.8.1–5.8.15. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0508s52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. A18 binds directly to IL-17RA.

Fig. S2. A18 specifically inhibits IL-17A–induced gene expression.

Fig. S3. A18 alleviates TH17 cell–mediated, but not TH1 cell–mediated, EAE in mice.

Fig. S4. HFD-induced asthma is attenuated in IL-17RC–deficient mice.

Fig. S5. HDM- and CFA-induced asthma is alleviated in IL-17RC–deficient mice.

Fig. S6. Analysis of the C6–C3–C6 flavonoid skeleton and of the hydroxyl groups of A18 that are critical to inhibit IL-17A signaling.