Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine perceived relationship power as a mediator of the relationship between intimate partner violence (IPV) and mental health issues among incarcerated women with a history of substance use. Cross-sectional data from 304 women as part of the Criminal Justice Drug Abuse Treatment Studies (CJ-DATS) were used to evaluate this hypothesis. Regression analyses examined the mediation relationship of perceived relationship power in the association between a history of IPV and mental health issues. Results supported the hypothesis, suggesting that perceived relationship power helps to explain the association between IPV and mental health issues. Implications of the findings for the provision of services to address the needs of these women are discussed, including assessment of perceived relationship power and focusing counseling interventions on women’s experiences with power in intimate relationships.

Keywords: relationship power, intimate partner violence, incarcerated women, mental health, relational model

The number of women incarcerated in prisons has increased 825% since 1973 (Harrison & Beck, 2006). Many of these women enter prison with mental health issues (James & Glaze, 2006; Sacks, 2004; Staton, Leukefeld, & Webster, 2003), suggesting the importance of identifying the mental health needs of incarcerated women, as well as the factors associated with those needs. Overall, 73.1% of female inmates in state prisons, 61.2% of female inmates in federal prisons, and 75.4% of female inmates in local jails reported a mental health issue at the time of incarceration (James & Glaze, 2006). The most commonly reported issues include anxiety and depression, although incarcerated women also report other mental health issues, including posttraumatic stress disorder (Sacks, 2004; Staton et al., 2003). Women who present with mental health problems also report other issues, such as a history of victimization. For example, among women with mental health issues, 68% reported past physical or sexual abuse compared with 44% of women who did not report any mental health issues, which suggests the need to explore factors contributing to mental health issues (James & Glaze, 2006). The purpose of this article is to examine two associated factors, intimate partner violence (IPV) and perceived relationship power, and evaluate a model in which perceived relationship power serves as a mediator of the relationship between IPV and mental health issues among incarcerated women with a history of substance use.

IPV

One factor that may contribute to women’s mental health issues is IPV, which can denote the aggregate of a variety of behaviors perpetrated by a current or former intimate partner, including physical aggression, psychological abuse, stalking, and sexual abuse (Jordan, Campbell, & Follingstad, 2010; Worell & Remer, 2003; World Health Organization, 2002). IPV occurs at epidemic proportions in the general population despite increased awareness and prevention efforts (Kilmartin, 2010; Worell & Remer, 2003; World Health Organization, 2002). Overall, male intimate partners perpetrate violence against more than 1.5 million women each year in the United States (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). IPV is especially prevalent among incarcerated women, with more than 70% of incarcerated women reporting a history of IPV (Browne, Miller, & Maguin, 1999; Zust, 2009). This rate is considerably higher than the general population, suggesting the importance of examining the consequences of this experience for incarcerated women.

IPV and Mental Health Issues

IPV can contribute to mental health issues experienced by victims. Fear and stress associated with violence may lead to posttraumatic stress among victimized women (Campbell, 2002; Hedtke et al., 2008; Jordan et al., 2010). Furthermore, victimized women can report negative emotional experiences such as shame, guilt, self-blame, and feelings of worthlessness associated with their victimization (Worell & Remer, 2003), which often lead to depression and anxiety, possibly resulting from IPV (Campbell, 2002; Coker et al., 2002; Hedtke et al., 2008; Jordan et al., 2010; Loxton, Schofield, & Hussain, 2006; World Health Organization, 2002). Research also suggests that mental health issues are proportionally related to the number of lifetime experiences of abuse, with more violence exposure incrementally increasing the risk of mental health issues (Hedtke et al., 2008). Given the high prevalence of IPV experiences among women in prison, it is possible that these IPV experiences are contributing factors to mental health issues.

Theoretical Framework

IPV can increase with perceived unequal power in relationships (Worell & Remer, 2003). Power can be defined as the “ability to access personal and environmental resources to effect personal and/or external change” (Worell & Remer, 2003, p. 78). Specific to intimate relationships, Pulerwitz, Gortmaker, and DeJong (2000) explain, “Relationship power is expressed via decision-making dominance, the ability to engage in behaviors against a partner’s wishes, or the ability to control a partner’s actions” (p. 640). Consequently, women who experience IPV may also experience a decreased perception of relationship power with their intimate partner. In addition, relationship power research indicates that this variable mediates the association between IPV and depression among female college students (Filson, Ulloa, Runfola, & Hokoda, 2010), which suggests that relationship power is important to consider when mental health and IPV are examined.

Women often define their sense of self through their relationships, which is described in the Relational Model (Gilligan, 1982; Miller, 1976). Intimate relationships may have a unique effect on a woman’s sense of self because the assumed level of commitment suggests the relationship is safe and trusting (Staton-Tindall et al., 2007). When intimate relationships become abusive, however, women may shape their sense of self in the context of the abuse. Consequently, women in physically and emotionally abusive relationships may struggle with their sense of self because of their lack of relationship power, which may lead to increased mental health issues. This struggle may be prevalent among substance-using, incarcerated women, suggesting the need to systematically explore the role of perceived relationship power in the relationship between mental health issues and IPV. The Relational Model seems to provide a context to understand how perceived relationship power influences the association between IPV and mental health issues.

Substance use, particularly alcohol use, has also been found to be highly associated with incidences of IPV and provides an even more nuanced understanding of the role of perceived relationship power (Campbell, 2002; Coker et al., 2002; Fals-Stewart, Golden, & Schumacher, 2003; Golinelli, Longshore, & Wenzel, 2009; Hedtke et al., 2008; Jordan et al., 2010; World Health Organization, 2006). Some authors suggest male partners may coerce women to engage in illegal activities that often result in the woman’s incarceration (Richie & Johnson, 1996) by using knowledge of a woman’s substance use to maintain power in the relationship (Frank & Rodowski, 1999). Others suggest that substance use is associated with mental health issues because the use of substances decreases the emotional pain associated with victimization (Ehrmin, 2002; Martin, English, Clark, Cilenti, & Kupper, 1996). These findings illustrate the importance of exploring the relationship between IPV and mental health issues among incarcerated women substance users specifically.

Present Study

Little is known about the unique power dynamics of intimate partner relationships among substance-using incarcerated women (Knudsen et al., 2008). Although a substantial portion of women are incarcerated for a drug-related offense (United States Department of Justice, 2000), many incarcerated women become involved in criminal behavior because of male manipulation and control (Frank & Rodowski, 1999; Zust, 2009). Consequently, male partners can coerce women to engage in illegal activities that often result in a woman’s incarceration (Richie & Johnson, 1996). Therefore, it is particularly important to examine relationship power dynamics among incarcerated women.

The literature indicates that incarcerated women experience mental health issues and disproportionate rates of IPV (Browne et al., 1999; James & Glaze, 2006; Sacks, 2004; Staton et al., 2003; Zust, 2009). Although the role of relationship power in the association between IPV and mental health symptoms has been examined among female college students (Filson et al., 2010), this model has not been examined among incarcerated women. Exploring the role of perceived relationship power among these women addresses a gap in the literature with implications for treatment. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine the relationship among IPV, perceived relationship power, and mental health issues in a sample of incarcerated women to determine whether the previous finding that powerlessness mediates the relationship between IPV and depression applies to incarcerated women as well. Because substance use is associated with IPV and mental health, only incarcerated women who self-reported substance use were included. The following hypotheses guided this study:

-

Hypothesis 1

IPV, perceived relationship power, and mental health issues will be significantly related.

-

Hypothesis 2

Perceived relationship power will mediate the relationship between IPV and mental health issues.

Method

Participants

Cross-sectional, correlational data are included from 304 incarcerated women recruited from correctional facilities in Kentucky, Connecticut, Delaware, and Rhode Island. Female inmates were considered eligible if they had any history of at least weekly substance use prior to incarceration, were within 6 to 8 weeks of a parole hearing or anticipated release date, were at least 18 years old, and consented to participate. Exclusion criteria consisted of self-reported psychotic features within the last month, unique parole conditions that would complicate protocol implementation such as being paroled out of state, and/or a lack of participation willingness.

Procedures

Data collected as part of the NIDA-funded Criminal Justice Drug Abuse Treatment Studies (CJ-DATS) Cooperative Agreement between March 2007 and April 2008 were used for this study. The research team received approval to conduct the study from Institutional Review Boards at all associated sites (see Staton-Tindall et al., 2007). The overall purpose of the project was to evaluate the effectiveness of a six-session gender-specific Reducing Risky Relationships for HIV protocol with incarcerated women. This protocol sought to address women’s “thinking myths” related to behaviors that may increase their risk of contracting HIV. Prison staff provided a list of potential participants to research team members based on the eligibility criteria. Research staff then sent letters to each incarcerated woman inviting her to a screening session. During the screening session, research staff described the study and obtained informed consent from inmates who were eligible and willing to participate, emphasizing confidentiality of information. Eligible participants were then scheduled for a 2-hr, structured, face-to-face interview, which was conducted approximately 1 week after the screening session. Participants received a US$20 honorarium for their participation in the study. The present project utilized data collected during the baseline interview with participants.

Measures

Demographic information

Demographic information was collected with the CJ-DATS Core Questionnaire (see CJ-DATS, 2005; www.cjdats.org), which included circumstances prior to incarceration. Demographic characteristics included race/ethnicity (White or women of color), marital status (single, never married, or ever married), pregnancy status (yes or no), number of children, living situation (street, institution, own home, someone else’s home, halfway house, residential treatment, or other), education level (years of education), and employment status (full-time, part-time, unemployed and looking, disabled, volunteer, retired, unemployed and not looking, in school, armed forced, homemaker, or other). The severity of substance use index variable was created by summing self-reported substance use in the 6 months prior to incarceration for each substance. Participants indicated their use as never, 1–3 times, 1 time/month, 2–3 times/month, 1 time/day, 2–3 times/day, and 4 or more times daily for each substance. This method has been used in previous studies (Staton-Tindall et al., 2008).

IPV

IPV was measured with participants’ self-reported experience of verbal violence (example question: My partner insulted or swore at me) and physical violence (example question: I had a broken bone from a fight with my partner) by an intimate partner in the 6 months prior to incarceration. Participants who were not involved in an intimate relationship in those 6 months were asked to reflect on their most recent intimate relationship when answering the associated questions. This variable was created using the Psychological Aggression and Physical Assault subscales of the Conflict Tactic Scale 2 (CTS-2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996), which has demonstrated internal consistency reliability (α = .79 for psychological aggression and α = .86 for physical assault) and construct validity, established through previous investigations of the convergent validity between this scale and other similar measures with the specific population of incarcerated women (Jones, Ji, Beck, & Beck, 2002). The variable was scored using standardized procedures, which included summing the midpoints of the response categories (Straus et al., 1996). The midpoints included 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 15, and 25; therefore, higher numbers indicated more IPV experiences. Thus, the scores represent the total number of experiences of both psychological aggression and physical assault reported by the participants during their intimate relationship prior to incarceration. The response not in the past year, but it did happen before was not included. Internal consistency reliability of the scores in this sample were adequate (α = .92 for the full scale; α = .74 for psychological aggression; and α = .93 for physical assault).

Perceived relationship power

Perceived relationship power was defined as the participant’s perception of control and decision-making dominance in intimate relationships using the Sexual Relationship Power Scale (SRPS; Pulerwitz et al., 2000), which includes two subscales. The Relationship Control subscale measures the perception of power in the relationship and the Decision-Making Dominance subscale assesses which partner(s) had a role in making specific decisions within a relationship. The combined subscales produce an overall perceived relationship power score with higher numbers indicating more perceived relationship power. The scale scores have appropriate internal consistency reliability (α = .84) and construct validity, established through previous investigations of the convergent validity of this scale and other seemingly related constructs, such as a history of physical or sexual violence and safe sex behaviors (Pulerwitz et al., 2000). For the present study, established methods were used for scoring (Pulerwitz et al., 2000). The subscales had different response categories, so they were standardized and then combined as a mean and a standardized score with internal consistency reliability at α = .91.

Mental health issues

Mental health issues were measured using the CJ-DATS Core Questionnaire (see CJ-DATS, 2005; www.cjdats.org) for selected lifetime mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, hallucinations, trouble concentrating, and suicidal thoughts for 2 weeks or more and a previous suicide attempt. An example of the associated items includes not counting the effects from alcohol or other drug use, in your lifetime have you ever experienced serious depression; in your lifetime have you ever experienced anxiety or tension; in your lifetime have you ever experienced trouble understanding, concentrating, or remembering as well as questions related to the remaining mental health issues with response options yes or no for all items. Responses were summed to create a mental health index score, which ranged from 0 to 6. Internal consistency reliability of the scores in this study were adequate (α = .72).

Statistical Analyses

Based on previous research (Filson et al., 2010), it was hypothesized that IPV, perceived relationship power, and mental health issues would be significantly related and perceived relationship power would mediate the relationship between IPV and mental health issues. Hypothesis 1 was examined using bivariate correlations to understand the relationship among the variables of interest. The second hypothesis, which addressed the possible mediation, was assessed using separate regression analyses followed by a test for indirect effects (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Marital status and substance use severity index were used as control variables in these equations. Marital status was dichotomized as ever married or never married and substance use severity was created by summing participants’ use of all substances in the 6 months prior to incarceration in the analyses. For the first regression equation, perceived relationship power was regressed on IPV to examine whether the independent variable, IPV, significantly predicted the potential mediator, perceived relationship power. The next analysis assessed whether IPV significantly predicted the dependent variable, mental health issues, by regressing mental health issues on IPV. For the final regression equation, mental health issues were regressed on both IPV and perceived relationship power to determine whether the effect of IPV on mental health issues decreased when perceived relationship power was included in the model as a predictor. The final step of the analytic plan was to use the bootstrapping method to test further the indirect effects of the mediation model (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). This analysis is nonparametric and therefore does require data to be normally distributed thus providing a more robust assessment of the indirect effect of perceived relationship power on the association between IPV and mental health issues.

Results

Participants

The sample is profiled in Table 1. The median age was 35, and the majority of participants identified as Caucasian (68.0%) and reported less than 12 years of education (55.3%). Half of the participants lived in someone else’s apartment/house/room (50.0%) prior to incarceration and more than a quarter was employed full-time (29.9%). The most common marital status was single and never married (45.7%) with an average of 2.4 children. A profile of the self-reported substances used in the 6 months prior to incarceration is included in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic Profile of Sample (N = 304).

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 35 (19–68) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 206 | 68.0 |

| African American | 74 | 24.3 |

| Other | 14 | 4.6 |

| Native American | 2 | 0.7 |

| Asian | 1 | 0.3 |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 139 | 45.7 |

| Divorced | 75 | 24.7 |

| Legally married | 39 | 12.8 |

| Separated | 36 | 11.8 |

| Widowed | 8 | 2.6 |

| Living as married | 7 | 2.3 |

| Number of children, average (range) | 2.38 (0–11) | |

| Pregnant | 57 | 20.0 |

| Living situation | ||

| Someone else’s apartment/house/room | 152 | 50.0 |

| Own apartment/house/room | 118 | 38.8 |

| Street | 18 | 5.9 |

| Institution | 6 | 2.0 |

| Halfway house | 4 | 1.3 |

| Other | 3 | 1.0 |

| Residential treatment | 2 | 0.7 |

| Years of education, average | 10.97 | |

| Less than 12 years of education | 168 | 55.3 |

| Employment status prior to incarceration | ||

| Employed, full-time | 91 | 29.9 |

| Unemployed, not looking | 53 | 17.4 |

| Unemployed, looking | 41 | 13.5 |

| Employed, part-time | 39 | 12.8 |

Table 2.

Self-Reported Substance Use During 6 Months Prior to Incarceration.

| Substance | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | 226 | 74.3 |

| Crack | 166 | 54.6 |

| Marijuana | 156 | 51.3 |

| Cocaine | 112 | 36.8 |

| Non-prescription librium | 102 | 33.6 |

| Non-prescription methadone | 48 | 15.8 |

| Methamphetamine | 38 | 12.5 |

| Heroin | 33 | 10.9 |

| Hallucinogens | 13 | 4.3 |

| Barbiturates | 13 | 4.3 |

Descriptive Information

Participants reported an average of 18.81 (SD = 40.80) experiences of IPV in their lifetime, which ranged from 0 to 325 incidents. The average perception of relationship power reported was 2.74 (SD = .55) on the 1 to 4 scale, and the majority of participants reported high relationship power (score range 2.821–4; n = 145, 47.7%). The remainder described their perceived relationship power as low (score range = 1–2.430; n = 69, 22.7%) or medium (score range = 2.431–2.820; n = 90, 29.6%) based on standardized cutoffs (Pulerwitz et al., 2000). Participants reported an average of 2.10 (SD = 1.67) of six symptoms of mental health issues. Descriptive information is included in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive Information and Intercorrelations for Variables of Interest.

| Variables | % (n) | M | SD | IPV | PRP | MH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPV | 18.81 | 40.80 | — | −.32** | .18* | |

| Psychological aggression | 2.64 | 4.36 | ||||

| Physical assault | 0.77 | 2.71 | ||||

| Perceived relationship power | 2.74 | 0.55 | — | — | −.19** | |

| Mental health issues | 2.10 | 1.67 | — | — | — | |

| Anxiety | 58.6 (178) | |||||

| Depression | 55.6 (169) | |||||

| Trouble concentrating | 47.7 (145) | |||||

| Suicidal thoughts | 22.0 (67) | |||||

| Suicide attempts | 20.1 (61) | |||||

| Hallucination | 5.6 (17) |

Note: IPV = intimate partner violence; PRP = perceived relationship power; MH = mental health issues. The mental health issues data include the percentage of participants who endorsed experiencing the symptom in their lifetime.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Bivariate Relationships

Bivariate correlations were used to conduct analyses of the relationship among variables. Findings indicated that the relationship between the number of IPV experiences and mental health issues was positive and statistically significant, r = .18, p = .002, suggesting more IPV experiences were associated with an endorsement of more mental health issues. Furthermore, the relationship between perceived relationship power and mental health issues was negative and statistically significant, r = −.19, p = .001, indicating that less perceived power in relationships was associated with more mental health symptoms. Finally, perceived relationship power and the number of IPV experiences were negatively correlated at a statistically significant level, r = −.32, p < .001, suggesting more IPV experiences were associated with lower perceived power in relationships. These intercorrelations are included in Table 3.

Mediation Model

Hypothesis 2 stated that perceived relationship power would mediate the relationship between IPV and mental health issues. Analyses were first conducted to determine whether any demographic variables had a differential effect on the variables of interest to partial out this variance in the regression analyses. The substance use severity index was associated at a statistically significant level with each variable of interest (IPV, r = .16, p = .005; perceived relationship power, r = −.16, p = .043; mental health issues, r = .12, p = .037). Furthermore, findings from a t test indicated women who were ever married reported significantly more experiences with IPV (M = 24.10, SD = 51.09) compared with women who were never married (M = 12.52, SD = 21.90), t(302) = −2.486, p = .013. Although previous literature suggests age and IPV are associated (Abramsky et al., 2011), age was not significantly associated with IPV in this sample, r = .057, p = .325, so it was not included in the model. Based on the literature (Coker et al., 2002; Jordan et al., 2010; World Health Organization, 2006) and the preliminary analyses indicating that substance use severity and marital status were significantly associated with the variables of interest, both were treated as control variables for each regression equation.

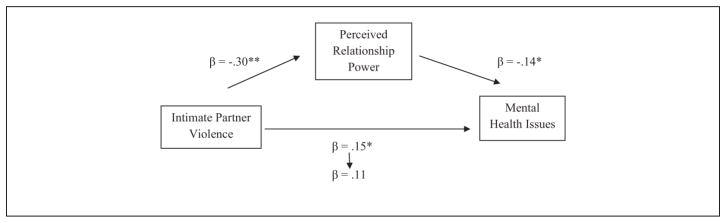

Analyses followed the recommendations of Baron and Kenny (1986) and Preacher and Hayes (2008) to examine a mediation model for Hypothesis 2. The first step of this process required regressing perceived relationship power on IPV. This model was statistically significant, R2 = .11, F(3, 297) = 12.37, p < .001, with IPV (B = −.004, β = −.30) having a statistically significant regression weight, t(297) = −5.30, p < .001. The second step required regressing mental health issues on IPV, which was also statistically significant, R2 = .04, F(3, 297) = 4.28, p = .006, with IPV (B = .01, β = .15) having a statistically significant regression weight, t(297) = 2.56, p = .011. The last regression model regressed mental health issues on both IPV and perceived relationship power. This model was also statistically significant, R2 = .06, F(4, 296) = 4.52, p = .001, and perceived relationship power (B = −.41, β = −.14) had a statistically significant regression weight, t(296) = −2.25, p = .025. The regression weight for IPV (B = .01, β = .11) was no longer significant, t(296) = 1.81, p =.072, in the final model. These analyses indicated that perceived relationship power helped explain the association between IPV and mental health issues because the effect of IPV on mental health issues in the third equation was less (β = .11) than in the second equation (β = .15) and became nonsignificant when the effect of perceived relationship power was introduced. This finding was supported by the Sobel test, z = 2.05, p = .04. Bootstrapping methods to assess the indirect effects provided further support for the mediation, with a 95% confidence interval [.0004, .0037]. Because IPV no longer predicted mental health issues when perceived relationship power was introduced into the equation and both the Sobel test and bootstrapping method supported the mediation model, the data supported Hypothesis 2. The regression equations are included in Table 4, and the mediation model is illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analysis Predicting Mental Health Issues in the Third Step of the Mediation Model (N = 304).

| Predictor | R2 | β | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | .02 | ||

| Marital status | .76 | .19 | |

| Substance use composite | .11 | .05 | |

| Step 2 | .06 | ||

| Marital status | .05 | .40 | |

| Substance use composite | .08 | .19 | |

| IPV | .11 | .07 | |

| Perceived relationship power | −.14 | .03 |

Note: IPV = intimate partner violence.

Figure 1.

Illustration of perceived relationship power as a mediator of the association between intimate partner violence and mental health issues.

*p < .05. **p < .01

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine perceived relationship power as a mediator of the relationship between IPV and mental health issues among incarcerated women with a history of substance use. It was hypothesized that IPV, perceived relationship power, and mental health issues would be significantly associated and that perceived relationship power would mediate the relationship between IPV and mental health issues.

Preliminary analyses indicated IPV was significantly and positively associated with mental health issues, which suggests that more IPV experiences are associated with more mental health issues, a finding consistent with other studies (Campbell, 2002; Coker et al., 2002; Jordan et al., 2010; Loxton et al., 2006; World Health Organization, 2002), especially research indicating that more incremental violence exposure increases the risk of mental health issues (Hedtke et al., 2008). Therefore, it is important to assess for a history of IPV among incarcerated women and to evaluate potential mental health needs of women with prior victimization. Furthermore, perceived relationship power was significantly and negatively associated with mental health issues. The data suggested that less perceived relationship power was associated with more mental health issues, which is consistent with previous findings (Filson et al., 2010). Furthermore, perceived relationship power was significantly and negatively associated with the number of IPV experiences, indicating that less perceived relationship power was also associated with more IPV experiences. This finding is also consistent with existing literature (Filson et al., 2010). While the only previous study that examined this question was with college students (Filson et al., 2010), these results suggest perceived relationship power can provide information about the relationship between IPV and mental health issues among substance-using incarcerated women. This finding suggests that prison assessments could incorporate women’s experiences in relationships as important indicators of treatment needs. These findings are also meaningful because they begin to provide a systematic assessment of perceived relationship power missing in the literature.

The hypothesis that perceived relationship power would mediate the relationship between IPV and mental health issues was supported. This finding is consistent with other studies (Filson et al., 2010) and extends previous findings to incarcerated, substance-using women. The mediating role of perceived relationship power suggests that the association between IPV and mental health issues can be explained by the perception of relationship power. This finding is consistent with the Relational Model, suggesting that women in physically and emotionally abusive relationships experience mental health issues in part because of their lack of relationship power in the intimate relationship. Therefore, it is important to focus on perceived relationship power among women offenders with a history of IPV as one factor to address these mental health issues. In addition to assessing for IPV and mental health issues, it is also important to assess perceptions of power in relationships to target interventions. This treatment goal could help sustain improvements in mental health symptoms by helping women learn to navigate power dynamics in relationships.

Limitations

A limitation is that data are correlational and cross-sectional, which affects interpretation because the temporal order of the variables of interest is unknown. It was hypothesized that IPV would predict mental health issues with perceived relationship power mediating the relationship based on the theoretical framework used in this study. The model was derived based on previous research, though the relationship among variables may be different than hypothesized. Specifically, variables were collected at the same time, so the directionality of the relationship among variables is unknown. Therefore, it is possible a different order accounts for the relationship among the variables as well. For example, women may experience a decrease in perceived relationship power following instances of IPV or they may experience increased instances of IPV following a decreased perception of relationship power. Future research will incorporate follow-up data to examine how perceived relationship power and mental health issues change over time, possibly leading to targeted treatment recommendations. Furthermore, participants were not asked to reflect on the same time period when answering questions related to all variables of interest; therefore, the association among these variables may be limited. Specifically, the IPV variable was based on experiences during the past 6 months prior to incarceration, the perceived relationship power is a global construct, and the mental health issues variables was based on the participants’ lifetime experience of the symptoms. Although the variables were significantly associated, the differences in their occurrence in the participants’ lives may limit the usefulness of the study.

The variables of interest were chosen for this study based on previous literature, although additional variables may also help explain the association between IPV and mental health issues, such as the length of time of the intimate relationship. This limitation should also be considered when exploring the usefulness of this study.

Furthermore, study findings can only be generalizable to women similar to the participants recruited for this project, incarcerated women with a history of substance use in the states from which the samples were drawn. Although the purpose of this study was to evaluate whether the previously determined mediation role of powerlessness in the relationship between IPV and depression among college students applied to incarcerated women, this study does not have implications for populations other than incarcerated women. Finally, study participants were predominantly White, so future studies should consider cultural factors associated with the mediating relationship power by replicating this study with other groups of women. The application of the Relational Model may be unique for the predominantly White women in this sample and may manifest differently in women of color who have different perceptions of power in intimate relationships.

Implications

Despite these limitations, findings from this study support the idea that IPV experiences of incarcerated women with a history of substance use are associated with perceived relationship power in their intimate relationships. This sense of limited relationship power, in turn, contributes to mental health issues. An awareness of this association can provide a framework for understanding the consequences of IPV among incarcerated women. Findings of this study also have implications for clinical practice including the importance of assessing for relationship power to help guide treatment interventions.

The mediating role of perceived relationship power in the association between IPV and mental health issues has broader implications for assessment with incarcerated, substance-using women. Incarcerated women who use mental health services may not disclose their history of violence because they are not aware of its affects on their mental health. Therefore, it is crucial for counselors to assess for violent experiences and perceptions of relationship dynamics, especially perceived relationship power among women offenders while addressing mental health issues. This focus would help both counselors and women become aware of the role of perceived relationship power to presenting mental health issues.

Once a woman and her therapist understand the association of perceived relationship power with IPV and mental health issues, treatment can directly focus on this connection. If perceived relationship power accounts for the mental health issues, it seems important to focus treatment efforts on improving the sense of power these women have in their intimate relationships. Treatment could address a woman’s ability to recognize relationships in which power is not shared and engage in relationships with shared power, thus increasing self-efficacy to identify future partners with whom to develop a healthy relationship based on mutual respect. Ultimately, these efforts will help women develop a stronger sense of self to participate in relationships with shared power rather than violence or abuse.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the collaborative contributions by federal staff from NIDA, members of the Coordinating Center (University of Maryland at College Park, Bureau of Governmental Research, and Virginia Commonwealth University), and the nine Research Center grantees of the NIH/NIDA CJ-DATS Cooperative (Brown University, Lifespan Hospital; Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services; National Development and Research Institutes, Inc., Center for Therapeutic Community Research; National Development and Research Institutes, Inc., Center for the Integration of Research and Practice; Texas Christian University, Institute of Behavioral Research; University of Delaware, Center for Drug and Alcohol Studies; University of Kentucky, Center on Drug and Alcohol Research; University of California at Los Angeles, Integrated Substance Abuse Programs; and University of Miami, Center for Treatment Research on Adolescent Drug Abuse).

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded under a cooperative agreement from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIH/NIDA) grant U01 DA16205.

Footnotes

The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH/NIDA or other participants in Criminal Justice: Drug Abuse Treatment Studies (CJ-DATS).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abramsky T, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C, Devries K, Kiss L, Ellsberg M, Heise L. What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:109–125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne A, Miller B, Maguin E. Prevalence and severity of lifetime physical and sexual victimization among incarcerated women. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 1999;22:301–322. doi: 10.1016/S0160-2527(99)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359:1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM, Smith PH. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;23:260–268. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criminal Justice-Drug Abuse Treatment Studies. Criminal justice drug abuse treatment studies: Adult core intake. 2005 Available from www.cjdats.org.

- Ehrmin J. That feeling of not feeling: Numbing the pain for substance dependent African American women. Qualitative Health Research. 2002;12:780–791. doi: 10.1177/10432302012006005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Golden J, Schumacher JA. Intimate partner violence and substance use: A longitudinal day-to-day examination. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;33:1555–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filson J, Ulloa E, Runfola C, Hokoda A. Does powerlessness explain the relationship between intimate partner violence and depression? Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:400–415. doi: 10.1177/0886260509334401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank J, Rodowski M. Review of psychological issues in victims of domestic violence seen in emergency settings. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 1999;17:657–677. doi: 10.1016/S0733-8627(05)70089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan C. In a different voice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Golinelli D, Longshore D, Wenzel SL. Substance use and intimate partner violence: Clarifying the relevance of women’s use and partners’ use. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2009;36:199–211. doi: 10.1007/s11414-008-9114-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P, Beck A. Prisoners in 2005. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin; 2006. (NCJ 215092). Retrieved from http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/p05.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hedtke KA, Ruggiero KJ, Fitzgerald MM, Zinzow HM, Saunders BE, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG. A longitudinal investigation of interpersonal violence in relation to mental health and substance use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:633–647. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James D, Glaze L. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. 2006 (NCJ 213600). Retrieved from http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/ascii/mhppji.txt.

- Jones NT, Ji P, Beck M, Beck N. The reliability and validity of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2) in a female incarcerated population. Journal of Family Issues. 2002;23:441–457. doi: 10.1177/0192513X02023003006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan CE, Campbell R, Follingstad D. Violence and women’s mental health: The impact of physical, sexual and psychological aggression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:607–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-090209-151437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmartin C. The masculine self. 4. Cornwall-on-Hudson, NY: Sloan Publishing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Leukefeld C, Havens JR, Duvall JL, Oser CB, Staton-Tindall M, Inciardi JA. Partner relationships and HIV risk behaviors among women offenders. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40:471–481. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400653. Available from http://www.journalof-psychoactivedrugs.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loxton D, Schofield M, Hussain R. Psychological health in midlife among women who have ever lived with a violent partner or spouse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:1092–1107. doi: 10.1177/0886260506290290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S, English K, Clark K, Cilenti D, Kupper L. Violence and substance use among North Carolina pregnant women. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:991–997. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.7.991. Available from http://ajph.aphapublications.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JB. Toward a new psychology of women. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Gortmaker SL, DeJong W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles. 2000;42:637–660. doi: 10.1023/A:1007051506972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richie B, Johnson C. Abuse histories among newly incarcerated women in a New York City jail. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association. 1996;51:111–117. Available from http://www.amwa-doc.org/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks JY. Women with co-occurring substance use and mental disorders (COD) in the criminal justice system: A research review. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 2004;22:449–466. doi: 10.1002/bsl.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton M, Leukefeld C, Webster JM. Substance use, health, and mental health: Problems and service utilization among incarcerated women. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2003;47:224–239. doi: 10.1177/0306624X03251120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton-Tindall M, Leukefeld C, Palmer J, Oser C, Kaplan A, Krietemeyer J, Surratt HL. Relationships and HIV risk among incarcerated women. The Prison Journal. 2007;87:143–165. doi: 10.1177/0032885506299046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Staton-Tindall M, Oser CB, Duvall JL, Havens JR, Webster JM, Leukefeld CG, Booth BM. Male and female stimulant use among rural Kentuckians: The contribution of spirituality and religiosity. Journal of Drug Issues. 2008;38:863–882. doi: 10.1177/002204260803800310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy E, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Prevalence and consequences of male-to-female and female-to-male intimate partner violence as measured by the National Violence Against Women Survey. Violence Against Women. 2000;6:142–161. doi: 10.1177/10778010022181769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Justice. Women offenders. 2000 Retrieved from http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/wo.pdf.

- Worell J, Remer P. Feminist perspectives in therapy: Empowering diverse women. 2. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World report on violence and health. 2002 Retrieved from www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/factsheets/en/ipvfacts.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Intimate partner violence and alcohol. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/factsheets/fs_intimate.pdf.

- Zust BL. Partner violence, depression, and recidivism: The case of incarcerated women and why we need programs designed for them. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2009;30:246–251. doi: 10.1080/01612840802701265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]