Abstract

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) awards rise during recessions. If marginal applicants are able to work but unable to find jobs, countercyclical Unemployment Insurance (UI) benefit extensions may reduce SSDI uptake. Exploiting UI extensions in the Great Recession as a source of variation, we find no indication that expiration of UI benefits causes SSDI applications and can rule out effects of meaningful magnitude. A supplementary analysis finds little overlap between the two programs’ recipient populations: only 28% of SSDI awardees had any labor force attachment in the prior calendar year, and of those, only 4% received UI.

I. Introduction

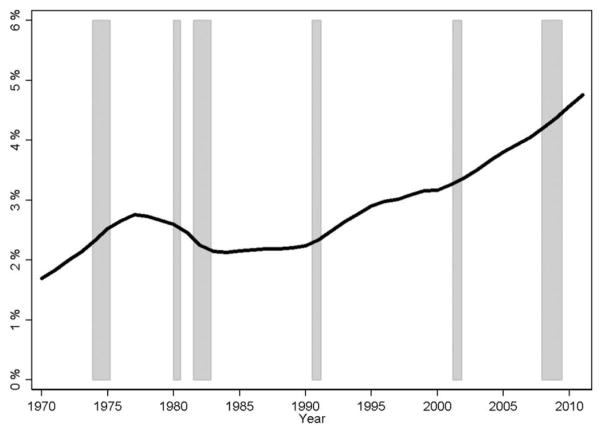

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) is a social insurance program that pays benefits to covered workers who have become disabled.1 Figure 1 shows that the share of the working-age population receiving SSDI has more than doubled since 1990; as of the end of 2012, 8.8 million adult Americans received SSDI benefits. The rapid growth has prompted concerns about SSDI’s fiscal sustainability (e.g., Autor and Duggan 2006).

Fig. 1.

SSDI recipients as share of civilian noninstitutional population aged 20–64, 1970–2011. SSDI recipients include disabled workers and spousal beneficiaries, and they are measured as of December 31 of each year. Shaded areas indicate recessions. Sources: Social Security Administration, Office of the Actuary, Bureau of Labor Statistics, and National Bureau of Economic Research.

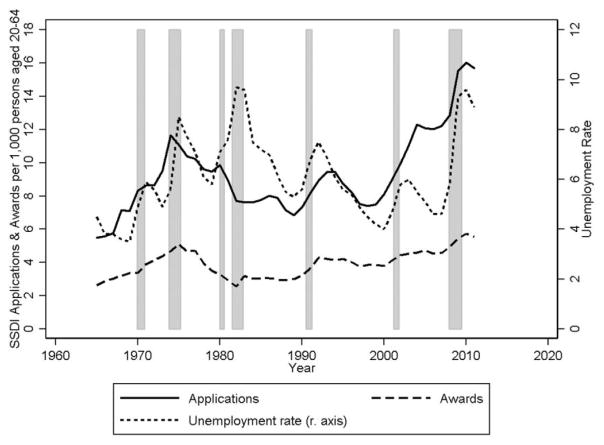

As figure 1 indicates, the growth rate of SSDI rolls accelerated during the recessions of the early 1990s and early 2000s, and perhaps during the 2007–9 recession as well. Figure 2 shows that since the mid-1980s, SSDI applications and awards (measured as shares of the working-age population) have risen in downturns, then fallen beginning a year or two after the unemployment peak (Black, Daniel, and Sanders 2002; Autor and Duggan 2003; Coe et al. 2011). Duggan and Imberman (2009) attribute nearly one-quarter of the rise in male SSDI participation between 1984 and 2003 to the recessions of the early 1990s and early 2000s.2 While the cyclical pattern has weakened since the late 1990s (von Wachter 2010), figure 2 still shows a substantial rise in awards between 2007 and 2011.

Fig. 2.

SSDI recipients as share of civilian noninstitutional population aged 20–64, 1970–2011. Applications and awards data apply to new disabled worker cases. Sources: Social Security Administration, Office of the Actuary, and Bureau of Labor Statistics.

One potential explanation for the countercyclical movement of SSDI applications and awards is that marginally disabled individuals who would work in good economic conditions instead, when times are bad, apply for SSDI. There are several potential mechanisms that might produce such a pattern. First, the SSDI screening process may in practice take economic conditions into account (along with impairment, age, and education) when assessing an applicant’s ability to work and therefore his eligibility for benefits. Second, employers may be less willing to make accommodations for individuals with moderately work-limiting disabilities when the labor market is weak.3 Third, because wages on new jobs typically decline during recessions while SSDI benefits depend on past wages, the relative generosity of SSDI rises in recessions, potentially leading displaced, marginally disabled workers to prefer SSDI over work (Black et al. 2002; Autor and Duggan 2003). Fourth, job search durations rise in recessions; displaced workers may turn to SSDI as a source of income during their jobless spells.

SSDI benefits typically extend until retirement age and include access to Medicare after 2 years on SSDI; those awarded SSDI benefits rarely return to work, perhaps due to high implicit taxes on earnings (Autor and Duggan 2006). Thus, if a temporary labor market downturn leads to an increase in SSDI applications, this could have permanent consequences. Insofar as some workers use SSDI to relieve income shocks, other safety net programs such as Unemployment Insurance (UI) may help to prevent this. For marginally disabled workers who are displaced but hope to work again when the economy recovers, UI claims should be attractive relative to an SSDI application: UI benefits are paid immediately and are straightforward to obtain, requiring only a minimal work history, a qualifying job loss, and minimal ongoing job search. In contrast, SSDI applicants go through extensive reviews and even if approved do not receive payments for many months.4

One would expect UI-SSDI program interactions to be important if many of the recession-induced SSDI applications come from individuals who were displaced from steady employment and are potentially capable of working again but are unable to find new work during bad economic times. A UI extension may enable some such individuals to find jobs before they turn to SSDI. On the other hand, if the countercyclical pattern of SSDI applications is driven by one (or more) of the other mechanisms discussed above, or if potential SSDI applicants do not qualify for UI, we do not expect important interactions between the two programs. Thus, evidence on the magnitude of UI-SSDI interactions would be informative about the types of shocks that drive the rise in SSDI applications in recessions and about the degree to which SSDI reforms might limit the payment of benefits to potential workers.

Evidence on UI-SSDI interactions is also important to UI program design. UI benefit durations are regularly extended during downturns. This may limit what would otherwise be even larger rises in SSDI applications. However, if UI and SSDI interact importantly, even longer extensions may be warranted.5 As we discuss below, SSDI savings could potentially be large relative to the cost of UI benefits.

This paper uses data from the Great Recession and its aftermath to investigate the relationship between UI exhaustion and SSDI applications. Potential UI benefit durations, usually just 26 weeks, reached as high as 99 weeks in 2009, remained high for several years, and then declined in 2012. At each point in this period, there was substantial cross-sectional variation. This meant that workers laid off at roughly the same time were eligible for very different UI durations depending on the location and exact timing of the layoff, and thus UI exhaustion rates varied substantially over time and across states. We use this variation to identify the effect of UI exhaustion on SSDI usage, using time-series analyses, state-by-month panels, and event studies of weekly SSDI applications surrounding UI extensions.

Several recent papers have explored UI-SSDI interactions. Lindner and Nichols (2012) use variation in benefit amounts and eligibility criteria to identify the causal effect of UI participation on SSDI application decisions. Rutledge (2012) uses both aggregate state-month application data and microdata from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) to examine the effect of UI benefit duration extensions on SSDI application decisions and allowance rates. He finds that individuals on extended UI benefits (but not those on regular benefits) are less likely to apply to SSDI than are those who have exhausted their UI benefits.

We extend the existing literature in three important ways. First, our conceptual model views UI extensions as a source of variation in the time to UI exhaustion rather than as a direct determinant of SSDI applications. Second, our empirical specifications are closely tied to this conceptual model and thus are easily interpretable in terms of the determinants of the underlying application decision. Third, we introduce two new data sources that have not been used previously to study UI-SSDI interactions. We have obtained access to micro administrative Social Security Administration (SSA) data that we use to tabulate weekly SSDI applications and the corresponding award rates. We also use matched Current Population Survey (CPS) samples to examine the pre-SSDI characteristics and labor force attachment of new SSDI recipients.

II. A Simple Model of Interactions between Unemployment Insurance and Disability Insurance

Autor and Duggan (2003) model the choice between work and SSDI application for marginally disabled workers. We extend their model to include unemployment insurance, drawing as well on Rothstein’s (2011) model of UI and job search. Each period a displaced worker can choose whether to search for work or to remain idle.6 Only search can lead to a new job or to UI benefits, whereas an SSDI application can be submitted only when idle.

The cost of search is cU and the probability of finding employment is f. If a job is found, it yields continuation value VE.7 Job searchers can draw up to N periods of unemployment benefits, worth bUI per period. Idle individuals do not pay search costs but have probability 0 of finding employment and cannot draw UI benefits.

In a period that an individual does not search, he may apply for SSDI benefits at application cost cA and with probability of success p. We assume that SSDI eligibility decisions are perfectly correlated over time, so that a worker who is rejected once will not reapply.8 A worker whose application is successful receives per-period benefits bDI in perpetuity.

This basic setup gives rise to a dynamic decision problem with state variables n, indexing the number of weeks of UI benefit entitlement remaining, and A ∈ {0, 1}, describing the worker’s SSDI entitlement. Here A = 0 indicates a worker who has not applied for SSDI benefits, and A = 1 indicates a worker who has applied but been rejected. We define U(n, A) as the value associated with entering a period without a job and with state variables {n, A}. Letting δ indicate the discount rate and u(y) indicate the flow utility associated with per-period cash income y, U(n, A) can be written as:9

where VU, VI, and VA represent, respectively, the values associated with choosing to search for a job, to remain idle, or to apply for benefits. These are

The first expression indicates that a worker choosing job search receives benefits (if he has benefits remaining) and pays a search cost. He then has a probability f of finding a job and receiving continuation value VE or a probability (1 − f) of entering the next period in unemployment, with one less period of benefits remaining. In the second expression, an idle worker pays no search costs and receives no benefits, and he enters the next period in the same state with probability 1. Finally, a worker who applies for SSDI does not draw on his UI benefits, but he pays an application cost and faces a probability p of being awarded SSDI benefits with continuation value VDI = u(bDI)/(1 − δ). A rejected applicant enters the next period with the same UI entitlement but having exhausted his SSDI options.

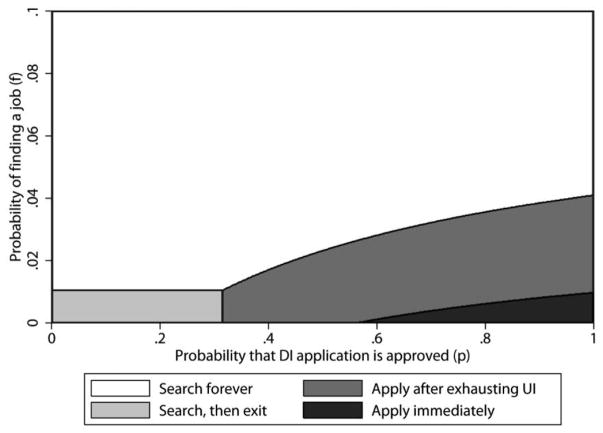

Workers’ policy choices will depend on the various parameters. Figure 3 shows how these choices vary with f and p for a particular set of other parameters. First, in the upper part of the figure, workers with high job finding probabilities search for work until they find jobs, even beyond the expiration of their UI benefits. Second, in the lower-left region, workers with low job finding probabilities but also low SSDI award probabilities search for work until their UI benefits are exhausted, then exit the labor force without applying for SSDI.10 Third, workers in the lower-right region, with very high SSDI award probabilities but very low job finding chances, simply apply for SSDI immediately after displacement, without ever looking for work. Some of these would search for work if rejected, but others would simply exit the labor force. A final group consists of workers with somewhat lower SSDI award chances and/or somewhat higher job finding probabilities, who search for work until their UI benefits are exhausted, then apply for SSDI benefits. This last type of worker can be deterred from applying for SSDI by a UI extension. Some such workers will still be jobless at the end of the extended benefits and will apply to SSDI then, but others will find jobs during the extended search period and thus be permanently diverted from the SSDI program.

Fig. 3.

Worker policies for job search and SSDI application, by likelihood of receiving SSDI benefits upon application (p) and job finding probability (f). See the text for description of model. Other model parameters are VE = 1/(1 − δ) (corresponding to a per-period wage normalized to 1 and a job that lasts forever); bUI = 0.4; bDI = 0.5; cU = 0.2; cA = 3; δ = 0.95; and u(y) = y.

The magnitude of this diversion could be substantial. To see this, suppose that {f, p} have a uniform distribution on [0, 0.1] × [0, 1] among displaced workers and that other parameters are as in figure 3. Then 17% of workers, and 35% of those who exhaust 26 periods of UI benefits, are of the UI-before-SSDI type. When UI benefits last for 26 periods, UI-before-SSDI workers comprise 83% of SSDI applicants and 79% of SSDI awardees. The average UI-before-SSDI SSDI applicant has f = 1.5%. Thus, some would find jobs if given longer UI benefit durations during which to search. A 26-period extension of UI benefits (to a total of 52 periods) would increase total UI payments by about 40% and would lead just under one-third of the UI-before-SSDI workers who exhaust their initial benefits to find new jobs before their extended benefits run out. This would reduce steady-state SSDI applications and awards by a bit over one-quarter.

An effect of this magnitude would be enormously important. Because individuals awarded SSDI benefits tend to draw them until retirement, the present value of a single SSDI award is around $300,000 (e.g., von Wachter, Song, and Manchester 2011). By comparison, weekly UI payments average around $300. Thus, our parameters imply that a 26-week UI extension would yield SSDI savings totaling more than three times the on-budget cost of that extension.

However the parameters used are just approximations, and the assumption of a uniform {f, p} distribution is entirely unsupported. It seems more likely, for example, that f and p are negatively correlated. This would increase the share of UI-before-SSDI workers, though perhaps it would also reduce their average job finding rates. The data may also differ from the predictions of the model if a substantial share of SSDI applications come from individuals who do not qualify for UI.

III. Data and SSDI Trends

We rely on three data sources to measure trends in SSDI application and receipt. First, we use publicly available tabulations from the Social Security Administration (SSA of SSDI applications at the state-by-month level between August 2004 and December 2012.11

Second, we obtained access to SSA’s Disability Research File, a restricted-access microdata file containing observations on 100% of individual SSDI applications in the period 2008–10, linked to application outcomes. We use these data to construct a state-by-week panel of application counts and award rates, defined as the share of applications each week that lead to awards by the end of 2010.12

Third, we use the Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) to the Current Population Survey (CPS).13 Respondents are asked in the spring about their income from various sources in the previous calendar year. We measure SSDI receipt as the presence of positive Social Security income for someone who names “disability” as one of the reasons. Due to the rotating panel structure of the CPS, we can match respondents in ASECs across 2 consecutive years.14 This allows us to measure new SSDI awardees’ earnings, employment, and self-reported disability status in the calendar year prior to the one in which benefits were awarded.

IV. Unemployment Insurance during the Great Recession and Its Aftermath

A. Extended UI Programs

Unemployment Insurance benefits are usually available for a maximum of 26 weeks. But at times during the past few years workers who have exhausted their regular UI benefits might have drawn as many as 53 additional weeks of Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) and as many as 20 more weeks of Extended Benefits (EB), bringing the total as high as 99 weeks. There has been substantial variation in this maximum over time and across states, resulting from differences in state policies, from changing federal law, and from “triggers” that conditioned both EUC and EB benefits on state economic conditions.

The EUC program was first authorized in June 2008.15 It initially provided 13 weeks of federally financed benefits. In November 2008, benefits were extended to 33 weeks in states with unemployment rates above 6% and to 20 weeks elsewhere. They were extended again in November 2009 to 34 weeks in low-unemployment states and 53 weeks in high-unemployment states. The program was initially set to expire in March 2009 but was extended several times thereafter. On a few occasions in 2010, the program expired temporarily for as long as 7 weeks before being reauthorized.

EUC complemented the preexisting EB program, which offered 13 or 20 weeks of benefits in participating states with high unemployment. Six states triggered on to EB benefits by January 2009. By May 2009, recipients in 27 states could receive EB benefits, and 11 of these offered 20 weeks of benefits. Eligibility continued to expand, with EB benefits flowing in between 36 and 39 states through most of late 2009, 2010, and early 2011.

Both EUC and EB benefits were gradually rolled back starting in mid-2011. The EB rollback was largely automatic, due to rules that condition eligibility on not just a high but also a rising unemployment rate. By July 2012, only Idaho was still paying benefits; it triggered off in early August. The major rollback of EUC began in February 2012. EUC durations were cut by up to 14 weeks, depending on the state unemployment rate. A schedule was also put in place establishing frequent changes in EUC durations through September 2012, when further cuts were scheduled. The program finally expired, apparently for good, in December 2013.

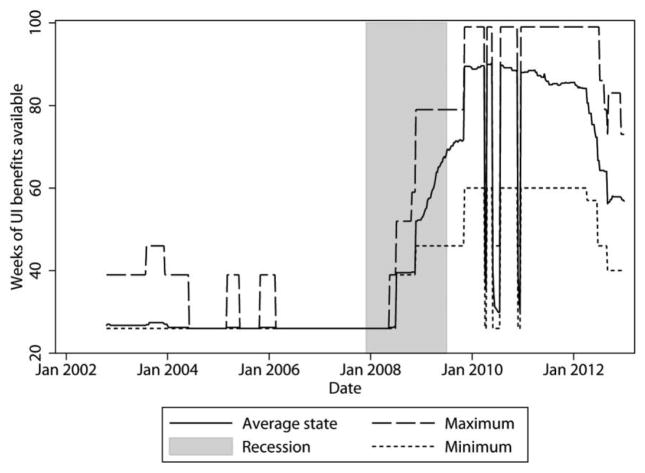

Figure 4 shows the average, minimum, and maximum number of weeks of benefits available over time through the recession, combining the regular, EUC, and EB programs. This figure is made from a database of UI availability at the state-by-week level, which was constructed by Rothstein (2011) but updated here to the end of 2012. Maximum benefit durations reached 99 weeks from late 2009 through mid-2012, and the average state was close to the maximum through much of this period. States began to fall away from the maximum during early 2012.

Fig. 4.

Unemployment Insurance benefit availability over the Great Recession. “Average state” series represents a simple, unweighted average across 50 states plus the District of Columbia.

The three expirations of the EUC program in 2010 are quite prominent in the figure. However, the sharp declines in durations indicated likely overstate the changes experienced by individual recipients. Although new regular benefit exhaustees were not permitted to begin EUC benefits after the program expired, EUC rules allowed many recipients who had already begun receiving EUC benefits to continue to draw benefits for several weeks. This tended to smooth over the expirations, limiting the disruption produced, though the amount of smoothing depended importantly on the exact date of job loss (Rothstein 2011).

Each eventual reauthorization provided for the retroactive payment of benefits to individuals who would have received EUC but for the temporary exhaustion. The long-term unemployed are unlikely to have substantial liquid savings or easy access to credit (Gruber 1997), however, so many may have felt serious financial crunches during the expirations (Rothstein and Valletta 2014).

B. Modeling Unemployment Insurance Exhaustion

The complex history of EUC and EB created a great deal of variation in the duration of UI benefits and thus in the timing of UI exhaustion. Unfortunately, while the Employment and Training Administration (ETA) compiles weekly counts of initial UI claims, no comparable data series is available for exhaustions. We take two approaches to approximating the number of exhaustions.

Our first exhaustion series is constructed from state-by-month level ETA data on first payments and final payments in each program and EUC tier.16 For each state in each month, we compute the number of final payments in any program or tier minus the number of first payments in the EUC tiers or EB. This closely approximates exhaustion, but there are three sources of slippage. First, we incorrectly count individuals who found new jobs or abandoned their job searches upon the expiration of a particular tier or program but who had more benefits available on another tier or program. Second, initial payments for a new program or tier may be recorded in the calendar month after that of the final payments from the prior program or tier. This creates excess volatility in measured exhaustions. Third, when EUC benefits were expanded—when new tiers were introduced, the program was retroactively reauthorized, or a state triggered on to new benefits—many people received first payments who had not received final payments in the previous week. We estimate negative numbers of exhaustions at these times. These moments are quite useful for identification of UI effects, however, as they represent periods when UI exhaustions were low or zero. We present analyses below that zero in on SSDI application dynamics surrounding UI extensions.

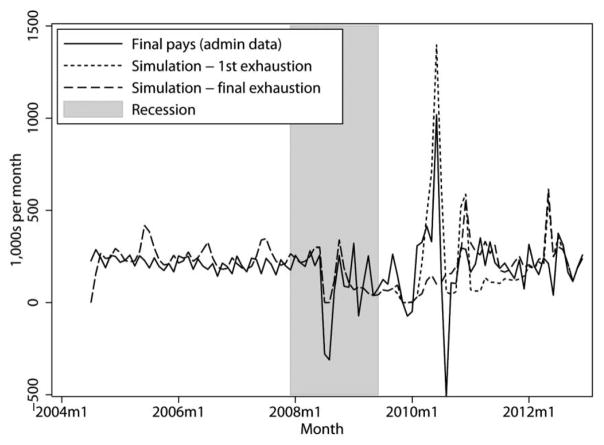

The solid line in figure 5 shows the estimated number of UI exhaustions each month using this method. Exhaustions were fairly stable, at around 210,000 per month, through early 2008. Measured exhaustions turned sharply negative in July and August of 2008, following the creation of EUC. They then fell and became more volatile, with two dips into negative terrain following EUC expansions in February and December 2009. Exhaustions spiked enormously during the temporary EUC expiration in June 2010, only to turn negative again in August 2010 after the program was reauthorized. Following this episode, the series has bounced around a level similar to that seen before the recession but higher than the 2008–9 average.

Fig. 5.

Estimates of the number of Unemployment Insurance exhaustions per month, 2004–12. “Simulation—1st exhaustion” series is censored at 1.4 million in June 2010; true value is 2.46 million.

Although the spikes and negative values represent measurement problems, the broad patterns—declines in exhaustions in 2009–10 followed by an increase in 2011–12—correspond to real dynamics. In 2009–10, benefit durations were quite long, and many recipients found jobs or exited the labor force before they exhausted benefits, while the cohorts that were approaching exhaustion were primarily those who had lost their jobs before the recession and hence were not particularly large. In the period 2011–12, durations remained long, but the large 2009 cohorts were exhausting their benefits, offsetting the effect of extended durations on the exhaustion rate.

Our second measure of UI exhaustions is designed to avoid spurious spikes and dips surrounding benefit expansions. We use our state-by-week database of UI availability to identify the week that each entering UI cohort would have exhausted its benefits, assuming eligibility for full benefits and continuous claiming. We measure the size of each entering cohort using weekly counts of initial claims for regular UI benefits by state. Next, we estimate the probability that an individual entering unemployment in each week would have survived in that status (rather than becoming reemployed or exiting the labor force) until the expiration of benefits. The survival probabilities are described in the appendix (available online); they are based on estimated average UI exit hazards that are allowed to vary smoothly over time and discretely with unemployment duration. The number of exhaustions produced by the cohort is estimated as the product of the size of the entering cohort with the probability of survival until exhaustion. We then aggregate across all cohorts that exhausted their benefits in each month to obtain state-by-month exhaustions.17

Two series obtained via this method are plotted in figure 5, corresponding to different definitions of “exhaustion.” The first series, plotted as a dotted line, judges an individual to have exhausted her benefits in the first week that she did not receive an on-time benefit payment, even if she was later paid retroactively for that week. This series mirrors the general trends in the administrative measure, but it shows zero exhaustions rather than negative numbers in months following EUC introduction and expansions. Like the administrative measure, however, it spikes sharply in June 2010, when EUC expired for 7 weeks. It is not clear whether this accurately reflects UI expirations relevant to SSDI application decisions. If recipients were confident that Congress would eventually reauthorize the program retroactive to its expiration, and if they had access to sufficient credit to borrow against their eventual benefits, this spike dramatically overstates the number of true exhaustions.

Our second simulated exhaustion series, graphed as a dashed line, counts individuals to exhaust their benefits only when they receive their final payments under any program, ignoring temporary breaks that are repaid retroactively. This does not spike in June 2010 and better matches the administrative series in 2011. We focus on this simulated final exhaustion series in the analyses below.

This series explains 9% of the month-to-month variation in the administrative data measure at the national level (and 21% when June-August 2010 are excluded). There is substantial across-state variation concealed behind the aggregate time series shown in figure 5. New York, for example, saw essentially zero exhaustions in 2008 and 2009, while Virginia saw as many or more exhaustions each month in 2008 as before the recession. In national data spanning the period 2008–12, state and month effects account for only 33% of the variance in state-by-month normalized exhaustions. 18 A natural concern is that the within-state, over-time variation in exhaustions may be particularly noisy. However, it does seem to have a substantial signal: the elasticity of the administrative data exhaustion measure with respect to our preferred simulated final exhaustions measure, controlling for state and month effects, is 0.24, with a standard error of 0.03. When we exclude the June–August 2010 period, the elasticity rises to 0.28.

V. Analyses of UI-SSDI Interactions Using Aggregate Data

The model in Section II suggests that some marginally disabled UI recipients might be induced to apply for SSDI benefits by the impending or actual exhaustion of their UI benefits. This would imply a positive correlation between UI exhaustions and SSDI applications. Insofar as the marginal SSDI applicants are less likely to be awarded benefits, it should also produce a negative correlation between UI exhaustions and SSDI acceptance rates.

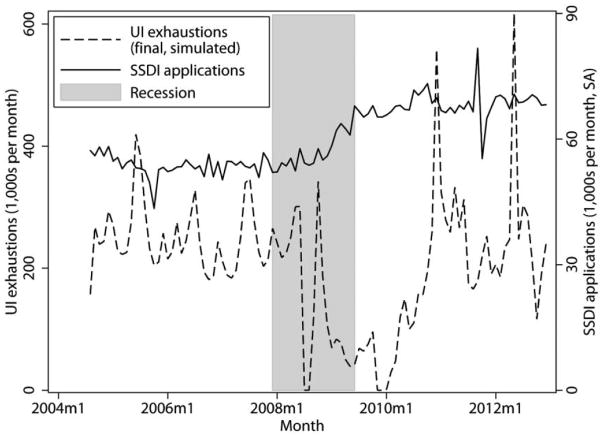

A. Time-Series Analyses

We begin by overlaying our simulated final UI exhaustion series with the number of monthly SSDI applications, in figure 6.19 There is little sign in this graph of a positive relationship between UI exhaustions and SSDI applications. Although UI exhaustions fell to well under half of their usual rate through most of 2009, SSDI applications rose by about 20% in the first half of 2009. The UI exhaustions returned to close to their precrisis level in late 2010; SSDI applications have remained roughly stable since mid-2009.

Fig. 6.

Unemployment Insurance exhaustions and Social Security Disability Insurance applications by month, 2004–12. Sources: Social Security Administration and authors’ calculations described in the text.

Table 1 presents time-series analyses of the log of seasonally adjusted aggregate monthly DI applications. The first column includes only the simulated number of final UI exhaustions in the month measured as a share of their average level during calendar years 2005–7. Since the dependent variable is also an index, the coefficient can be interpreted as an elasticity. It is negative, the opposite of the expected sign if UI exhaustions lead to SSDI applications, but insignificant and small. Adding a quadratic time trend (col. 2) has little effect on the point estimate. In column 3, the UI exhaustion coefficient becomes positive and marginally significant (t = 1.75) when the unemployment rate is controlled, but it remains small: a doubling of UI exhaustions is associated with a 1.3% increase in SSDI applications.

Table 1.

Time-Series Analysis of National Monthly Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) Applications

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final UI exhaustions (index: multiple of 2005–7 average) | −.047 (.046) | −.040 (.024) | .013 (.008) | .011 (.008) | .013 (.009) | |

| Exhaustions index (average, previous 3 months) | −.028 (.020) | |||||

| Exhaustions index (average, next 3 months) | .024 (.014) | |||||

| 𝟙(No exhaustions this month) | −.024 (.006) | |||||

| Unemployment rate (seasonally adjusted) | .039 (.003) | .032 (.006) | .027 (.006) | .033 (.005) | ||

| ln(initial UI claims) | −.040 (.019) | −.025 (.019) | −.043 (.018) | |||

| 𝟙(June, July, August 2010) | .037 (.009) | .034 (.008) | .033 (.009) | |||

| Post-ARRA | .054 (.019) | .061 (.020) | .047 (.018) | |||

| Quadratic time trend | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 101 | 101 | 101 | 101 | 95 | 101 |

Note.—Dependent variable is ln(SSDI applications), excluding concurrent SSDI/SSI applications, measured at the monthly level and seasonally adjusted. Sample in all columns is a national time series spanning August 2004 to December 2012 (November 2004 to September 2012 in col. 5). UI = Unemployment Insurance; ARRA=American Recovery and Reinvestment Act; SSI=Supplemental Security Income. Newey-West standard errors, allowing for autocorrelations at up to four lags, are in parentheses.

Column 4 adds several controls: the number of initial UI claims, seen as proxies for economic conditions; an indicator for June–August 2010 observations, when the EUC program temporarily expired; and an indicator for the period after February 2009. These have essentially no effect on the coefficient of interest.

Column 5 adds the averages of three leads and three lags of UI exhaustions. Each of these might capture true effects of UI exhaustions on SSDI applications, which need not be exactly contemporaneous. But while the lead effect is positive and marginally significant (t = 1.71), potentially indicating that people apply for SSDI a bit before they expect their UI benefits to expire, the lag effect is negative and larger, so the cumulative effect is only 0.001.

Finally, in column 6 we replace the counts of exhaustions with an indicator for the 4 months in which our simulations suggest that there were zero UI exhaustions, immediately following the introduction of the EUC program in mid-2008 and its expansion in late 2009. This specification indicates that SSDI applications fell 2.4% in these months. This is a somewhat larger response than implied by columns 3–5, but it is still not large.20

B. Panel Data Analyses

It is difficult in a time-series analysis to control for all potential spurious sources of co-movements. Moreover, a key source of exogenous variation in exhaustion rates—extensions and reductions in UI durations—is quite variable across states, which trigger on and off UI extension tiers and programs at various times. We thus prefer estimates based on the state-by-month panel. The panel dimension allows us to control for other factors that influence the time pattern of DI applications, identifying the exhaustion effect from differences across states in exhaustion trends. Estimates are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Panel Data Analysis of State-by-Month Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) Applications

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final UI exhaustions (index: multiple of 2005–7 average) | −.0025 (.0034) | −.0029 (.0035) | −.0029 (.0033) | −.0038 (.0025) | |

| Exhaustions index (average, previous 3 months) | −.0018 (.0067) | ||||

| Exhaustions index (average, next 3 months) | .0025 (.0069) | ||||

| 𝟙(No exhaustions this month) | .0176 (.0084) | ||||

| Unemployment rate (seasonally adjusted) | .0108 (.0055) | .0100 (.0055) | .0099 (.0055) | .0105 (.0055) | |

| ln(initial UI claims) | .0210 (.0324) | ||||

| State FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Month FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cubic UE rate control | Yes | ||||

| N | 5,151 | 5,151 | 5,151 | 4,845 | 5,151 |

| R2 | .987 | .987 | .987 | .987 | .987 |

Note.—Dependent variable is ln(SSDI applications), excluding concurrent SSDI/SSI applications, measured at the state-by-month level and seasonally adjusted. Panel ranges from August 2004 to December 2012 (November 2004 to September 2012 in cols. 4 and 5). UI = Unemployment Insurance; FE = fixed effects; UE= unemployment; SSI=Supplemental Security Income. Standard errors, clustered at the state level, are in parentheses.

Column 1 begins with a simple specification that includes state and month fixed effects, the state unemployment rate, and the state-level index of final UI exhaustions. The unemployment rate coefficient is positive and significant, though it is smaller than in table 1. The UI exhaustion coefficient is very close to zero. Moreover, it is extremely precisely estimated, with a standard error less than half of those in table 1, and thus rules out elasticities of SSDI applications with respect to UI exhaustions larger than 0.004 (at a 5% confidence level).

Columns 2 and 3 explore alternative controls for economic conditions, with little effect on the results. Column 4 includes lags and leads of the exhaustion index. These are both insignificant, and the point estimates indicate a cumulative elasticity of DI applications with respect to exhaustions of −0.0019.21 Finally, column 5 indicates that DI applications rise in months when new UI extensions take effect.

There are two sources of variation in our simulated UI exhaustion measure: variation in the size of entering UI cohorts (i.e., in the number of new claimants) and variation in the duration of UI benefits. Since the size of an entering UI cohort is determined by the economic environment at the time of entry into UI, which may have independent effects on DI applications, we have also created alternative simulations that hold the cohort size constant so that benefit durations are the only source of variation. When we use these as instruments for the original measures, results (not reported) are quite similar to those seen in table 2, and the upper bounds of the confidence intervals are if anything smaller.

One might expect that any individuals induced to apply for SSDI by the exhaustion of their UI benefits would have relatively mild disabilities and low award rates and thus that average award rates would fall for applicants from periods when UI exhaustions are high. Published data tabulate awards by the month of final adjudication rather than by the time of application, making it hard to discern changes in application quality. As an alternative, we use the SSA microdata to examine the acceptance rate for SSDI applications filed in each state in each month in 2008, 2009, and 2010.22 Table 3 presents results parallel to those in table 2. Each of the specifications shows an insignificant, near zero relationship between SSDI acceptance rates and UI exhaustions. The only exception is in column 4, where average exhaustions over the previous 3 months are significantly but positively related to the acceptance rate.23

Table 3.

Panel Data Analysis of Award Rates for New Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) Applications at State-by-Month Level

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final UI exhaustions (index: multiple of 2005–7 average) | .001 (.001) | .000 (.001) | .001 (.001) | .000 (.001) | |

| Exhaustions index (average, previous 3 months) | .008 (.003) | ||||

| Exhaustions index (average, next 3 months) | −.000 (.002) | ||||

| 𝟙(No exhaustions this month) | .001 (.002) | ||||

| Unemployment rate (seasonally adjusted) | −.009 (.004) | −.009 (.004) | −.008 (.004) | −.009 (.004) | |

| ln(initial UI claims) | .021 (.007) | ||||

| State FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Month FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cubic UE rate control | Yes | ||||

| R2 | .883 | .884 | .884 | .884 | .882 |

Note.—N= 1,836. Dependent variable is the fraction of SSDI applications that was awarded SSDI benefits, measured at the state-by-month level verifed from micro data. Panel ranges from January 2008 to December 2010. UI = Unemployment Insurance; FE = fixed effects; UE = unemployment. Standard errors, clustered at the state level, are in parentheses.

Taken together, the panel data analyses in tables 2 and 3 offer no sign that SSDI applications or awards respond to UI exhaustions. We can always rule out contemporaneous application elasticities larger than 0.005, and most specifications rule out elasticities smaller than that.

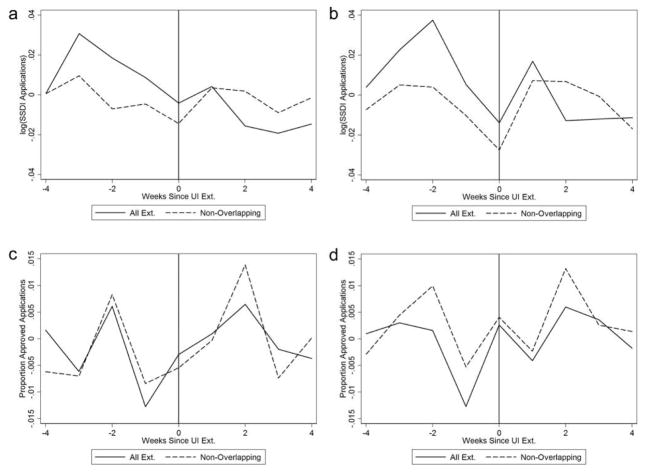

C. Event Analyses

We next use our administrative microdata to conduct event studies of weekly SSDI applications in the periods immediately surrounding extensions of UI benefits. These have several potential advantages over the analyses above. First, they do not require us to rely on our imperfect UI exhaustion measures; we can be confident that the flow of UI exhaustions declined drastically following new benefit extensions. Second, the event study framework allows us to more flexibly examine the time pattern of any application responses to UI extensions.24 Third, the main policy lever to reduce UI exhaustion is UI benefit extensions, so reduced form event studies of these extensions are directly informative about policy effects.25

One challenge in implementing the event study is that many states saw repeated UI extensions over relatively short periods in 2008 and 2009, which makes it difficult to distinguish long-run effects of one extension from short-run effects of the next. Thus, while a full assessment of the impact of UI extensions would consider the cumulated net effect, starting from the date that the extension is first anticipated and extending until well after the last cohort affected by the extension exhausts its UI benefits, we focus on shorter-run impacts and on extensions that do not closely overlap. We define event dates as the weeks on which UI extensions came into effect, as reported in “Trigger Notices” published by the US Department of Labor.

We use a state-by-week panel of log SSDI applications, which we denote NAPPst. We estimate specifications of the form:

where θt and γs are time and state fixed effects, respectively, is an indicator for a UI extension that went into effect in state s in week t − k, and we include dummies up until the end of our sample period. As a result, δk measures the difference from the national trend k weeks after (or |k| weeks before, when k < 0) a new UI extension, relative to the state’s difference more than 4 weeks prior to any extension, and Xst contains polynomials of degree three for the monthly state-level unemployment rate as well as the weekly state-level insured unemployment rate.

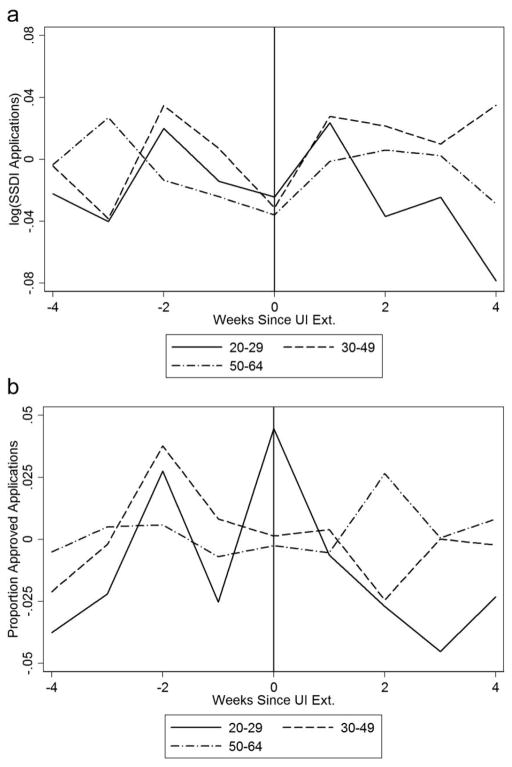

Figure 7 shows the δk coefficients for k ∈ {− 4, …, + 4}, that is, for the 4 weeks immediately preceding and following an extension in UI durations. Panels a and b show estimates for log weekly SSDI applications; panel b sets the D indicators to one only when the extension in question provided at least 13 weeks of additional benefits. Panels c and d show estimates for award rates. The corresponding coefficients, standard errors, and p-values are shown in appendix table A2 (tables A1–A6 are available online).

Fig. 7.

Extent Event studies of new UI extensions on weekly applications to Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and acceptance rates, by duration of UI extension and overlap with prior UI extensions. a, log(SSDI applications)—all extensions; b, log(SSDI applications)— 13+ week extensions; c, acceptance rate—all extensions; d, acceptance rate—13+ week extensions. Figure reports coefficients on dummies for weeks before or after a UI extension from regressions that include state and week fixed effects and cubic polynomials in the weekly insured unemployment rate and the monthly state unemployment rate. Panels b and d include lead and lag dummies only for extensions providing 13 or more weeks of additional benefits. Dashed series in each panel include lead and lag dummies only for extensions that do not occur within k weeks following a k-week prior extension, for any k. Coefficients are reported in appendix tables A2 and A3.

We begin with the results for SSDI applications, in panels A and B. These show a rise in SSDI applications in the weeks leading up to UI extensions. This is robust to a range of alternative specifications. We would not expect much of an anticipation effect in the event study, as many extensions were not easily predicted; moreover, this is the opposite of the expected sign.

Some of the extensions in our sample come close on the heels of prior extensions. These “overlapping” extensions should have no immediate effect on the number of UI exhaustions, as the preceding extensions already ensured that exhaustions would be close to zero. We therefore put more emphasis on results that focus on nonoverlapping extensions (shown as dashed lines in fig. 7).26 There is no rise in SSDI applications in the weeks preceding nonoverlapping extensions.

The solid lines drop slightly after extensions take effect, both in panel A and panel B. We can reject the hypothesis that the effects during the week of the extension and in the 4 weeks after the extension are jointly zero, and several of the individual coefficients are statistically significantly different from the pre-extension average. The estimates based on nonoverlapping extensions, however, show no drop in SSDI applications (save for a small statistically insignificant dip in the week of the extension).

Overall, the event study paints a mixed picture of the effect of UI extensions on SSDI application rates. On the one hand, the results that include all extensions suggest that there might be modest negative initial effects on SSDI applications, averaging around 2.5% (relative to the immediate pre-extension levels) over weeks 0–4. As exhaustion rates fall to zero during this period, this is somewhat larger than the upper bounds of the confidence intervals we obtained in the panel data analysis above. On the other hand, these effects are absent for nonoverlapping extensions, which are easier to interpret as policy experiments. Overlapping extensions have no immediate effect on UI exhaustions, as prior extensions have already ensured zero exhaustions in the short term, so it is surprising that these extensions appear to drive the effects we see.

Panels C and D of figure 7 repeat the event study analysis for SSDI award rates, computed as the share of applications that lead to eventual awards. The coefficients are shown in appendix table A3. There is no sign of a systematic effect of UI extensions on award rates along any dimension.

An advantage of the individual-level SSA data is that they permit us to disaggregate the analyses by demographic groups. Figure 8 shows event study estimates for three major age groups, focusing on large, nonoverlapping extensions. Estimates show no sign of systematic effects. Negative post-extension coefficients are nearly all for the youngest age group, which contributes the smallest share of SSDI applications, and these are never significant (individually or jointly).27 This confirms our interpretation of the event studies as consistent with the panel data analyses in indicating little overall effect of UI extensions on SSDI applications. The lower panel of figure 2 shows the effect on the acceptance rate by age group. Again, estimates are noisier for the youngest group but close to zero for the middle and older groups.

Fig. 8.

Event studies of new UI extensions, by age group: a, log(SSDI applications); b, acceptance rate. See the note to figure 7 for description of methods. Events are new UI extensions of 13 weeks or more that do not overlap with prior extensions. Coefficients are reported in appendix table A4.

D. The Potential Cost-Savings of UI Extensions

It is worth considering how large an effect would need to be to be quantitatively important. One way to approach this is to compare our empirical estimates to the elasticities implied by the stylized model in Section II. In that model, a doubling of UI durations reduced steady-state UI exhaustions by about half and steady-state SSDI applications by a quarter, implying a steady state elasticity of SSDI applications to UI exhaustions of 0.5. (The short-run elasticity is likely to be even larger.) Our empirical estimates imply substantially smaller UI exhaustion effects.28

Another way to assess the magnitude is to compare the cost of UI extensions to the resulting SSDI savings. As noted earlier, the present value of a SSDI award is around $300,000, while UI benefits cost around $300 per week. Thus, if extending UI benefits by 4 weeks diverts even four in 1,000 recipients from going on SSDI, the SSDI savings would pay the entire cost of the UI extension. Suppose that marginal SSDI applicants have monthly job finding rates of around 10% and SSDI award rates, if they apply, of around 60%.29 Then to be self-financing, a 4-week UI extension would need to deter 67 SSDI applicants from would-be exhaustees. 30 This almost certainly understates the needed amount of deterrence, as marginal SSDI applicants are probably less employable than the average long-term UI recipient and likely have lower award rates than average SSDI applicants.

Recall that our preferred estimates in table 2 indicated a negative elasticity of SSDI applications with respect to UI exhaustions, with relatively small standard errors, and that this ruled out an elasticity larger than 0.005. There are about one-fifth as many SSDI applications as UI exhaustions in a typical month (see fig. 6), so the upper bound of our confidence interval implies a reduction of just one SSDI application per 1,000 UI exhaustees whose benefits are extended.31 Even our estimates from the national time-series analysis (table 1), which indicated positive elasticities and had confidence intervals stretching as high as 0.035, imply reductions of no more than seven SSDI applicants, again far below the break-even point of 67 deterred SSDI applications. We thus conclude, based on our analysis of cell-level data, that any effect of UI exhaustion on SSDI applications is likely to be quite small.

VI. Lack of Overlap between Populations Affected by SSDI and UI

Our failure to find a larger effect is somewhat puzzling, given the rise in SSDI applications in recessions. As captured by our model, at least for previously employed SSDI applicants who suffered transitory employment shocks, UI should provide a means to smooth consumption that is more readily accessible than SSDI.

A potential explanation for a lack of correlation between SSDI applications and UI exhaustions is that the populations eligible for UI and applying for SSDI are distinct. One reason may be that evidence of UI income can be used against applicants in the SSDI screening process, discouraging potential SSDI applicants from taking up UI.32 Another reason may be that many potential SSDI applicants are not eligible for UI. UI eligibility requires earnings above a certain threshold in the period immediately preceding the claim, where SSDI eligibility depends on earnings over a longer period. A recurring concern has been that the UI earnings threshold may exclude workers with low earnings or unstable work histories. Insofar as those workers who are at risk of applying for SSDI have low earnings and unstable work histories, this may preclude them from applying to UI.33

To directly assess this hypothesis, we turn to our CPS ASEC sample. We focus on individuals in the 2005–13 surveys, matched to the same individuals’ responses in the prior year’s survey. This enables us to measure income and labor force participation in 2 consecutive years. We identify new SSDI recipients as those who report in their second survey that they had positive Social Security income due to disability in the preceding calendar year but who did not report income from this source during the year before that (in their responses to the first survey). We compare these new SSDI recipients to a similarly defined population of new UI recipients. Table 4 shows characteristics and employment outcomes of new SSDI and new UI recipients and for a residual category that did not receive either type of income in either year. The table confirms prior findings in the literature that individuals entering SSDI (col. 2) are substantially older and less educated than the broader population (col. 1). In contrast, new UI recipients (col. 3) are more similar to the residual population, although they are on average younger.

Table 4.

Selected Characteristics of new recipients of Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Unemployment Insurance (UI) in linked Current Population Survey samples

| No UI or SSDI in Either Year (Mean) | SSDI in y, Not in y − 1 (Mean) | UI in y, Not in y − 1 (Mean) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selected demographic characteristics, age-by-education (%): | |||

| < 50, noncollege | 26 | 28 | 37 |

| < 50, college | 43 | 13 | 35 |

| ≥ 50, noncollege | 12 | 38 | 14 |

| ≥ 50, college | 19 | 21 | 14 |

| Labor force in year y − 1 (from year y March supplement): | |||

| Any labor force attachment (%) | 83 | 28 | 92 |

| If any labor force attachment: | |||

| Weeks worked | 48.0 | 36.3 | 47.2 |

| Weeks looking for work | 1.4 | 5.4 | 2.9 |

| Weeks neither working nor looking | 2.6 | 10.4 | 2.0 |

| Any weeks looking (%) | 6 | 20 | 14 |

| Any weeks neither working nor looking (%) | 14 | 40 | 14 |

| Worked 48+ weeks (%) | 84 | 52 | 79 |

| Income in y − 1 (from year y March supplement): | |||

| Earnings > 0 (%) | 82 | 26 | 91 |

| UI income > 0 (%) | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Work-limiting disability in y − 1 (%) | 5 | 61 | 5 |

| N | 243,016 | 3,873 | 7,136 |

Source.—Current Population Survey March supplements, 2005–13.

In the year before transiting to SSDI, new beneficiaries have quite low labor force attachment.34 Only 28% spent even a single week working or looking for a job (compared to 92% for new UI recipients). Only 20% of these—about 6% of all new SSDI beneficiaries—reported even a single week of job search. Only 3% of new SSDI beneficiaries reported any UI income in the prior year, matching the rate of the entire population. The final row of table 4 suggests that part of the reason for the low labor force attachment of eventual SSDI recipients may be that those who will receive SSDI report a high incidence of work-limiting disability, 61%, compared to 5% of UI recipients or the remaining population.

The model developed in Section II focused on recently displaced workers. The evidence in table 4 suggests that such workers comprise at most one-quarter of SSDI awardees. This implies that the elasticities that we predicted based on our model should be scaled down by a factor of roughly four. Alternatively, if one assumes that any effect of UI exhaustion on SSDI applications comes from the 28% of SSDI cases with prior labor force attachment, the application elasticity for this subgroup can be obtained by quadrupling the overall elasticity. This adjustment closes some, though not all, of the gap between our model’s (coarse) predictions and the confidence intervals around our estimates.

As the 28% of SSDI awardees with prior labor force attachment must be central to any UI-SSDI interaction, we examined their characteristics specifically. These individuals average about 36 weeks of work in the year prior to the one in which they first received SSDI (see table 4) and earn an average of $641 per week (see appendix table A5). Although the latter is about two-thirds of the mean for the entire population, it corresponds to approximate annual earnings of $23,000. This represents enough earnings to qualify for UI if displaced, and earnings at this level would yield UI benefits in the same range as SSDI benefits. Yet, even in this subgroup with labor force attachment, only 4% receives UI income. (The number rises to 10% if one also counts UI receipt in the same calendar year as the initial SSDI payment.)

It seems clear, then, that the UI and SSDI populations are substantially distinct. This offers a resolution to the discrepancy between our model’s predictions and the estimates in Section V. It does not explain, however, why so few of the 28% of SSDI recipients who are likely to be eligible for UI try out UI before going onto SSDI.

Prior work has documented statistically significant negative causal effects of SSDI awards on subsequent labor force participation, implying that at least some SSDI awardees are capable of work, while our model suggested that any worker with a probability of finding a new job above a minimal level should use UI to support a job search before applying to SSDI. But these results are not as discrepant as they first appear, as the estimated disemployment effects of SSDI apply only to very specific subsamples of SSDI applicants. Maestas, Mullen, and Strand (2013), for example, use random assignment of applicants to SSDI examiners who vary in their likelihood of awarding benefits to generate exogenous variation in SSDI awards. They find that 25% of applicants are “marginal,” in the sense that they would be awarded benefits if assigned to the most generous examiner but not if assigned to the stingiest, and that for these marginal applicants the award of SSDI benefits reduces later employment by 20 percentage points.

If one assumes that awardees who are nonmarginal in the Maestas-Mullen-Strand analysis will not return to work, with or without benefits, then the implied share of awardees who would work in the absence of SSDI is only about 5%. This is not substantially different from the 3% of all awardees we identify with positive UI income in the calendar year prior to the award. (Note also that the size of the Maestas-Mullen-Strand marginal group corresponds closely to the SSDI awardees we see in the CPS with recent labor force attachment.) The Maestas-Mullen-Strand evidence is thus consistent with the idea that UI-supported job search is not a viable choice for the vast majority of SSDI applicants.

VII. Conclusion

This paper has used the uneven extension of UI benefits during and after the Great Recession to isolate variation in UI exhaustion that is not confounded by variation in economic conditions more broadly. Using a variety of analytical strategies, we have examined the relationship between UI exhaustion and uptake of SSDI benefits. None of the analyses presented here indicate a meaningful relationship. Although we cannot rule out small effects, all of the analyses rule out elasticities of SSDI applications with respect to UI exhaustion larger than 0.035, far too small to account for the cyclical pattern of SSDI application or to contribute meaningfully to the cost-benefit analysis of UI extensions.

An important caveat is that we must make assumptions about the timing of SSDI applications and awards induced by UI exhaustion. Since we use aggregated data, we have to assume that any induced applications occur within 3 months (before or after) of the date of UI exhaustion. There may be effects at longer lags; for example, UI exhaustees may wait 6 months or more before applying for SSDI. Thus, a causal link between UI exhaustion and SSDI cannot be conclusively ruled out.

Nevertheless, the analysis here counsels against the likelihood of such a link. Our analysis of CPS data suggests a potential explanation: the populations served by SSDI and UI are substantially distinct. During the calendar year prior to the one in which SSDI benefits were first received, only one-quarter of future SSDI awardees had any labor force attachment, only 6% spent any time looking for work, and only 3% received UI benefits.

Our results suggest that SSDI savings do not contribute importantly to the cost of UI extensions. They also suggest looking elsewhere for explanations for the countercyclicality of SSDI applications. For example, the cyclical pattern may reflect variation in the potential reemployment wages of displaced workers (Davis and von Wachter 2011), changes in the employment opportunities of the marginally disabled, or changes in SSA’s judgment of an applicant’s potential to work. These alternative explanations have quite different policy implications than would a link to UI. It is not clear, for example, that more stringent functional capacity reviews would reduce recession-induced SSDI awards if these awards reflect examiners’ judgments that the applicants are truly not employable in the extant labor market.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Hansman, Erik Johnson, Jeehwan Kim, and Ana Rocca for excellent research assistance, and David Pattison for generous help with tabulating the administrative microdata files from the US Social Security Administration. Rothstein is grateful to the Russell Sage Foundation and the Center for Equitable Growth at University of California, Berkeley, for financial support. Mueller and von Wachter’s research was supported by the US Social Security Administration through grant no. 1 DRC12000002-01-00 to the National Bureau of Economic Research as part of the SSA Disability Research Consortium. The findings and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the views of SSA, any agency of the federal government, or the NBER. E-mail the authors, Andreas Mueller at amueller@columbia.edu, Jesse Rothstein (corresponding author) at rothstein@berkeley.edu, and Till von Wachter at tvwachter@econ.ucla.edu. Information concerning access to the data used in this article is available as supplementary material online.

Footnotes

To become covered by SSDI, an individual has to have worked at least 20 quarters of the last 10 years (less if younger than 31; more if older than 42). Once covered, eligibility requires a disability that is expected to last at least 12 months and that prevents “Substantial Gainful Activity” (SGA; defined in 2013 as earnings of at least $1,020 per month). Another program, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), provides means-tested disability benefits, regardless of work history. SSI caseloads have also grown rapidly.

Other contributing factors include an aging population, increased female labor force participation (which increases women’s eligibility for SSDI benefits), more generous benefits, rising income inequality, and changes in the disability determination process (Duggan and Imberman 2009).

Relatedly, accommodation requirements and bans on discrimination are better enforced for incumbent workers than for new applicants. Recessions may break already disabled workers’ existing job matches, making it harder for them to obtain needed accommodations.

Although difficult to compare, SSDI benefits are likely a bit more generous than UI for typical applicants with low prior earnings, while UI slightly dominates for those with higher earnings. The average effective replacement rate under UI is around 50% of immediate pre-displacement earnings, but weekly benefits are capped. SSDI benefits are a nonlinear function of average monthly earnings in all years since the recipient turned 21 (up to a maximum of 35 years).

Many models show that UI should be more generous during recessions (e.g., Landais, Michaillat, and Saez 2010; Schmieder, von Wachter, and Bender 2012), as moral hazard costs are relatively low and consumption smoothing benefits high when unemployment is elevated. UI-SSDI interactions would provide a separate reason, not incorporated in these models, for countercyclical UI extensions.

As UI benefits are paid only to workers who are involuntarily displaced, we focus on workers who prefer work to SSDI application so will not voluntarily quit their jobs to apply for SSDI benefits.

This encompasses both the wage and the likelihood of subsequent displacement. Our interest is in decisions after an initial displacement, so decomposing these components is unnecessary.

Autor et al. (2015) find that less than 15% of applicants whose claims are denied are receiving benefits 5 years later. Some or all of these may reflect new or worsened disabilities after the initial application. Allowing for reapplication would complicate the model substantially but would not change the basic predictions.

Because we assume that parameters are stationary, it can be shown that any worker who chooses search with n ≠ 1 will also choose search the following period. The max operators in the V expressions are thus relevant only for n = N and n = 1.

With the parameter values used, job search is worthwhile for the duration of UI benefits even if the job finding probability is zero as the UI benefit is larger than the search cost. If bUI is low enough relative to cU, however, a policy of exiting the labor force immediately after job loss becomes optimal for low-f, low-p workers.

This information is available at http://www.socialsecurity.gov/disability/data/ssa-sa-mowl.htm. We exclude concurrent SSDI/SSI applications and SSI-only applications, but results are robust to including them.

Our measure understates eventual award rates, particularly for applications near the end of our panel. All of our analyses of award rates include calendar time effects.

The ASEC is known as the “March CPS.” The sample is taken from the regular monthly CPS: the full March sample and portions of the February, April, and November samples are used.

CPS respondents who move between surveys cannot be matched. We are able to match around 75%of ASEC respondents between year y and year y+1 ASECs; 6%–8% of ASEC-to-ASEC matches show discrepancies in age, race, gender, or education, and these are discarded. Fig. A1 in the online appendix compares the number of SSDI recipients identified in the CPS with SSA caseloads. The latter includes recipients living in institutions (prisons, etc.), who are excluded from the CPS sample. Despite this, the CPS series matches the level and the overall trend of SSDI receipt quite well.

See, e.g., Fujita (2010) and Rothstein (2011) for more detailed discussions.

EUCbenefits are divided into tiers. In 2010, there were four tiers, offering 20, 14, 13, and 6 weeks of benefits; the latter two were available only in high-unemployment states. The multi-tier structure has little effect on recipients but is used in record-keeping.

There is an additional adjustment to account for claims that do not lead to benefit payments.

There are many state-month cells with zero exhaustions. Rather than logging the measure, we normalize monthly exhaustions in each state by the average number of monthly exhaustions in the state in the period 2005–7. We use the normalized series for all further analyses.

We focus on applications for SSDI but exclude applications to SSI as well as concurrent SSDI/SSI applications. Results are similar when we include SSI and concurrent SSDI/SSI applications.

We have also explored specifications using our alternative measures of UI exhaustion (the dotted and solid lines from fig. 5). These were not significantly related to SSDI applications in the time series. See Mueller, Rothstein, and von Wachter (2013).

This figure is calculated by cumulating unrounded coefficients, then rounding. The rounded coefficients reported in the table cumulate to −.0017.

Appendix table A1 (online) reports application analyses conducted using only the period covered by the microdata. Results are similar to those in table 2.

We do not analyze the time series of award rates, as the censoring of post-2010 awards in our data creates a strong trend in measured award rates.

In another attempt to estimate exhaustion effects robust to timing concerns, we used microdata from matched CPS files (discussed in Sec. VI) to estimate the effect of exhausting UI before June 30 on the probability of receiving SSDI income in the same calendar year (see Mueller et al. 2013). Estimates were imprecise, but they are of very similar magnitude to those in table 2.

One can interpret the event study estimates as the “reduced forms” corresponding to two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimators in which UI benefit extensions are used as instruments for UI exhaustion. We discussed 2SLS estimates like this above.

In the non–overlapping extensions specifications, is an indicator for a new extension in week t − k that did not follow an earlier x week extension by less than x weeks, for any x. When excluding overlapping extensions from our treated group, we add them to the control group.

The only statistically significant post-extension coefficient is for the acceptance rate of applications filed by 50–64-year-olds 2 weeks after an extension, and this is the wrong sign.

If only a fraction of SSDI applicants come from employment and only these applicants respond to UI extensions, the predicted elasticity from the model needs to be scaled down accordingly. We discuss this in Sec. VI.

See Rothstein (2011) on job finding and von Wachter et al. (2011) and Maestas et al. (2013) on SSDI award rates.

Among the 67 deterred applications, on average 40 would be successful. Of these 40, four would find jobs during the UI extension and thus be (semi-)permanently diverted from SSDI. The remaining 36 would simply be awarded SSDI benefits 4 weeks later than they would have without the extension, generating minimal savings.

The calculation follows from the elasticity formula , where UI and SSDI are counts of individuals.

To be eligible for SSDI, workers have to state that they cannot engage in SGA and cannot have engaged in SGA for a waiting period of 5 months.

More generally, it is well documented that the take-up rate of UI among unemployed workers is far from unity and that correspondingly UI recipients tend to have somewhat higher average earnings and stable job attachment (e.g., Rothstein 2011; Rothstein and Valletta 2014).

Because SSDI income is measured on a calendar year basis, our “prior year” measures effectively refer to a 12-month period beginning 12–23 months before the first SSDI payment.

Contributor Information

Andreas I. Mueller, Columbia University, National Bureau of Economic Research, and IZA

Jesse Rothstein, University of California, Berkeley, and National Bureau of Economic Research.

Till M. von Wachter, University of California, Los Angeles, National Bureau of Economic Research, and IZA

References

- Autor David H, Duggan Mark G. The rise in the disability rolls and the decline in unemployment. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2003;118(1):157–206. [Google Scholar]

- Autor David H, Duggan Mark G. The growth in the Social Security disability rolls: A fiscal crisis unfolding. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2006;20(3):71–96. doi: 10.1257/jep.20.3.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autor David H, Maestas Nicole, Mullen Kathleen J, Strand Alexander. NBER Working Paper no. 20840. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: 2015. Does delay cause decay? The effect of administrative decision time on the labor force participation and earnings of disability applicants. [Google Scholar]

- Black Dan, Daniel Kermit, Sanders Seth. The impact of economic conditions on participation in disability programs: Evidence from the coal boom and bust. American Economic Review. 2002;92(1):27–50. doi: 10.1257/000282802760015595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe Norma B, Haverstick Kelly, Munnell Alicia H, Webb Anthony. Working Paper no. 2011–23. Center for Retirement Research, Boston College; 2011. What explains state variation in SSDI application rates? [Google Scholar]

- Davis Steven J, von Wachter Till. Recessions and the costs of job loss. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 2011;43(2):1–72. doi: 10.1353/eca.2011.0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan Mark, Imberman Scott A. Why are the disability rolls skyrocketing? The contribution of population characteristics, economic conditions, and program generosity. In. In: Cutler David M, Wise David A., editors. Health at older ages: The causes and consequences of declining disability among the elderly. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Shigeru. Business Review. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia; 2010. Economic effects of the unemployment insurance benefit; pp. 20–27. 4th quarter. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber Jonathan. The consumption smoothing benefits of Unemployment Insurance. American Economic Review. 1997;87(1):192–205. [Google Scholar]

- Landais Camille, Michaillat Pascal, Saez Emmanuel. NBER Working Paper no. 16526. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: 2010. Optimal unemployment insurance over the business cycle. [Google Scholar]

- Lindner Stephan, Nichols Austin. Working Paper no. 2012-2. Center for Retirement Research, Boston College; 2012. The impact of temporary assistance programs on disability rolls and re-employment. [Google Scholar]

- Maestas Nicole, Mullen Kathleen J, Strand Alexander. Does Disability Insurance receipt discourage work? Using examiner assignment to estimate causal effects of SSDI receipt. American Economic Review. 2013;103(5):1797–1829. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller Andreas I, Rothstein Jesse, von Wachter Till. NBER Working Paper no. 19672. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: 2013. Unemployment Insurance and Disability Insurance in the Great Recession. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein Jesse. Unemployment Insurance and job search in the Great Recession. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 2011 Fall;43:143–214. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein Jesse, Valletta Robert. Working Paper no. 2014-06. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco; 2014. Scraping by: Income and program participation after the loss of extended unemployment nenefits. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge Matthew S. Working Paper no. 2011–17. Center for Retirement Research, Boston College; 2012. The impact of Unemployment Insurance extensions on Disability Insurance application and allowance rates. (revised April 2012) [Google Scholar]

- Schmieder Johannes, von Wachter Till, Bender Stefan. The effects of extended Unemployment Insurance over the business cycle: Regression discontinuity estimates over 20 years. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2012;127(2):701–52. [Google Scholar]

- von Wachter Till. NBER Retirement Research Center Paper no. NB 10–13. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: 2010. The effect of local employment changes on the incidence, timing, and duration of applications to Social Security Disability Insurance. [Google Scholar]

- von Wachter Till, Song Jae, Manchester Joyce. Trends in employment and earnings of allowed and rejected applicants to the Social Security Disability Insurance Program. American Economic Review. 2011;101(7):3308–29. doi: 10.1257/aer.101.7.3308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.