Abstract

Study Design

A retrospective subgroup analysis was performed on surgically treated patients from the lumbar spinal stenosis (SpS) arm of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT), randomized and observational cohorts.

Objective

To identify risk factors for reoperation in patients treated surgically for SpS and compare outcomes between patients who underwent reoperation with those that did not.

Summary of Background Data

SpS is the most common indication for surgery in the elderly; however, few long-term studies have identified risk factors for reoperation.

Methods

A post-hoc subgroup analysis was performed on patients from the SpS arm of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT), randomized and observational cohorts. Baseline characteristics were analyzed between reoperation and no reoperation groups using univariate and multivariate analysis on data eight years post-operation.

Results

Of the 417 study patients, 88% underwent decompression only, 5% non-instrumented fusion and 6% instrumented fusion. At the 8 year follow up, the reoperation rate was 18%; 52% of reoperations were for recurrent stenosis or progressive spondylolisthesis, 25% for complication or other reason and 16% for new condition. Of patients who underwent a reoperation, 42% did so within 2 yrs, 70% within 4 years and 84% within 6 years. Patients who underwent reoperation were less likely to have presented with any neurological deficit (43% reop vs. 57% no reop, p=0.04). Patients improved less at follow-up in the re-operation group (p<0.001).

Conclusion

In patients undergoing surgical treatment for SpS, the reoperation rate at eight year follow-up was 18%. Patients with a reoperation were less likely to have a baseline neurological deficit. Patients who did not undergo reoperation had better patient reported outcomes at eight year follow up compared to those who had repeat surgery.

Keywords: spinal stenosis, spine surgery, Lumbar spine, reoperation, risk factors, patient outcomes, treatment effect

INTRODUCTION

SpS is the most common indication for surgery in the elderly and was the fastest growing indication for spine surgery in the last three decades.1–5 Although SpS may lead to significant disability, several well-designed prospective studies have documented the efficacy of timely surgical intervention for carefully selected patients.1–4,6,7 Recent changes in our healthcare system, technological advancements, and societal pressures have fueled the demand for cost effective, clinically effective, and durable surgical options. A recent report compared long-term health related quality of life (HRQoL), and cost per quality adjusted life years (QALY) in patients that had undergone surgery for SpS with patients who had undergone total knee or hip arthroplasty (TKA, THA).8,9 Despite a higher revision rate, significant improvement was observed in the HRQoL and QALY of the SpS patients, comparable to the TKA and THA patients. Furthermore, long-term benefits for SpS patients were sustained up to a mean 7 to 8 year follow up. Collectively, the literature supports the efficacy of surgery for SpS. However, the need for reoperation has been reported and concerns exist over potential increased costs and inferior outcomes among patients who require a revision.

Most of the current literature regarding risk factors for reoperation is from retrospective data, heterogenous patient groups, or limited demographic regions.5,10–13 Most studies comparing surgical outcomes for SpS include patients with underlying deformity or instability.6,10 An improved understanding of potential risk factors for revision surgery will serve to improve predictability of patient outcomes and cost effectiveness.

The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) is a large, multicenter, prospective study with strict inclusion criteria across three arms consisting of intervertebral disc herniation, degenerative spondylolisthesis and SpS.1,2 The SPORT database is unique in that it allows for analysis of patients with SpS without degenerative spondylolisthesis, as these patients were studied separately. The purpose of this study was to perform a subanalysis of the 8 year SPORT data to determine if patient baseline characteristics would emerge as risk factors for reoperation in patients treated surgically for SpS and compare outcomes between patients who underwent reoperation with those that did not.

Materials and Methods

This investigation was a retrospective subanalysis of prospectively-collected data from the SPORT trial. The data was based on data collected from enrollment in the initial SPORT study through eight year follow-up.

Study Design

Patient Population: The SPORT trial is a multicenter study carried out among 13 institutions in 11 states across the United States. The study includes both randomized and observational cohorts using validated primary and secondary outcome measures (Short-Form 36 [SF-36], AAOS/Modems version of the Oswestry Disability Index [ODI], patient-reported improvement, satisfaction with current symptoms and care, Stenosis Bothersomeness Index [SBI], and the Leg pain and Low Back Pain Bothersomeness Scale). Further details of the original SpS arm of the SPORT study have been reported elsewhere. 3,4

Patients included in the SpS arm of the SPORT trial had neurogenic claudication or radicular leg symptoms for at least 12 weeks and spinal stenosis seen on cross-sectional imaging at one or more levels. Exclusion criteria included patients with fixed or unstable lumbar spondylolisthesis (translation of more than 4mm or 10 degrees of angular motion between flexion and extension on upright lateral radiographs), or spondylolysis.

A research nurse at each site identified participants and verified eligibility with use of a shared decision-making video. Enrollment began in March of 2000 and ended in November 2004. Follow-up was at 6 weeks, 3 months, 1 year, 2 years, 4 years, 6 years and 8 years post-enrollment.

Surgical intervention

The protocol surgical intervention was a standard posterior decompressive laminectomy. If, at the time of surgery, the surgeon believed that the patient required a procedure that differed significantly from the protocol (e.g. the addition of an arthrodesis) the patient remained a study patient and the specifics of the procedure performed were recorded on the surgical treatment form.

Study Measures

Primary endpoints were the Short-Form 36 bodily pain and physical function scores (SF-36 BP and PF), as well as the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI). Secondary outcomes included patient reported self-improvement, Stenosis Frequency Index (SFI), Stenosis Bothersomeness index (SBI), Low Back Pain Bothersome Index, Leg Pain Bothersome Index, satisfaction with current symptoms and care, and work status.

Patient characteristics included age, gender, work lift demand, race, education, marital status, work status, compensation, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, hypertension, diabetes, osteoporosis, depression, heart problem, joint problem, time since most recent episode began, expectation of being free of pain with surgery, expectation of being free of pain with nonoperative treatment, opioid use, injections, physical therapy, use of antidepressants, taking NSAID, missed work, predominant back pain, and low back pain severity.

Operative characteristics measured included procedure type (decompression only, non-instrumented fusion, instrumented fusion), multi-level fusion, decompression level, number of levels decompressed, operative time, blood loss, blood replacement, length of hospital stay, and complications.

Intra-operative complications included dural tear or spinal fluid leak or “other” intra-operative complications. Post-operative complications were measured up to 8 weeks post-operatively and included wound hemotoma and wound infection, or “other” post-operative complications. Bone graft complications, CSF leaks, cauda equina injury, wound dehiscence, and pseudoarthrosis were assessed but did not occur in this group.

Statistical Considerations

A subgroup analysis was performed on surgically treated patients in the SpS arm of the SPORT trial, including both randomized and observational cohorts. In this analysis, patients were stratified into no reoperation versus reoperation groups and statistical analysis compared the two groups.

Baseline characteristics, operative factors, complications, and medical events in the reoperation and no reoperation groups were compared using a chi-square test for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. To analyze the risk factors for reoperation, Cox’s proportional hazards model was used to explore which variables maintained significance after adjusting for other variables in the model. Variables significant at p<0.10 were candidates for inclusion in the final multivariable regression model. Final selection for the model was done using the stepwise method as implemented in SAS, which sequentially enters the most significant variable with p<0.10 and then after each entered variable removes variables that do not maintain significance at p<0.05. Age and gender were forced to be in the model.

Primary outcomes analyses compared the reoperation and no reoperation groups using changes from baseline at each follow-up, with a mixed effects longitudinal regression model including a random individual effect to account for correlation between repeated measurements within individuals. The analyses were adjusted for age, sex, compensation, baseline score of stenosis bothersomeness index, income, smoking status, stomach problem, joint problem, diabetes, duration of most recent episode, treatment preference, baseline score (for SF-36 and ODI), and center. Across the eight-year follow-up, overall comparisons of “area-under-the-curve” between groups were made using a Wald test. Computations were done using SAS procedure PROC MIXED for continuous data and PROC GENMOD for binary outcome (SAS version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 based on a two-sided hypothesis test with no adjustments made for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Index patient population

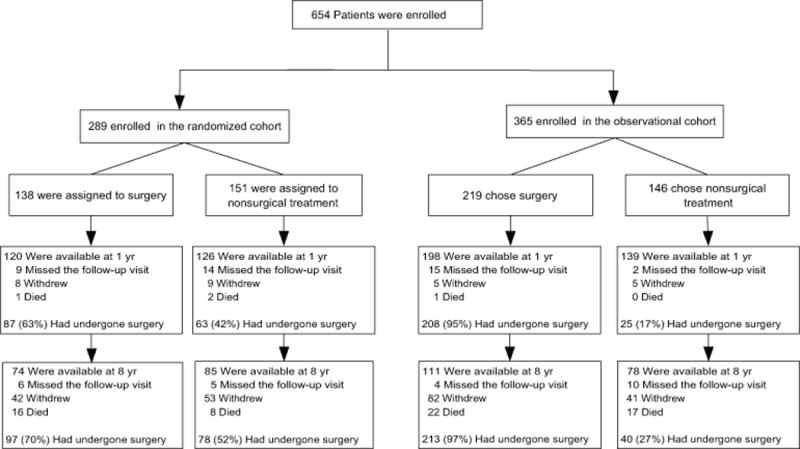

Overall, in the SpS arm of the SPORT trial, 289 patients were enrolled to the randomized cohort and 365 were enrolled to the observational cohort. By 8 years, 70% of those randomized to surgery and 52% of those randomized to non-operative treatment had undergone surgery,constituting a total of 428 patients, of which, 422 had at least 1 follow-up and were included in the analysis (Table 1). Of these, 417 had adequate data on surgery to be included in the analysis of operative treatment and complications (Table 2). Patients were lost to follow-up due to dropping out of the study, missed visits, or death (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Patient baseline demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and health status measures according to whether the patient had revision surgery within 8 years of index surgery.

| SPS | Had Revision Surgery (n=77)* |

No Revision Surgery (n=345) |

p-value*** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 62.4 (10.2) | 64.2 (12.5) | 0.24 |

| Female - no. (%) | 25 (32%) | 137 (40%) | 0.29 |

| Ethnicity: Not Hispanic† | 75 (97%) | 330 (96%) | 0.70 |

| Race - White | 63 (82%) | 292 (85%) | 0.66 |

| Education - At least some college | 48 (62%) | 217 (63%) | 0.97 |

| Marital Status - Married | 56 (73%) | 250 (72%) | 0.92 |

| Work Status | 0.75 | ||

| Full or part time | 30 (39%) | 119 (34%) | |

| Disabled | 8 (10%) | 32 (9%) | |

| Retired | 33 (43%) | 155 (45%) | |

| Other | 6 (8%) | 39 (11%) | |

| Compensation - Any‡ | 6 (8%) | 24 (7%) | 0.99 |

| Mean Body Mass Index (BMI), (SD)§ | 30 (5) | 29.3 (5.3) | 0.30 |

| Smoker | 7 (9%) | 31 (9%) | 0.85 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 33 (43%) | 149 (43%) | 0.94 |

| Diabetes | 13 (17%) | 45 (13%) | 0.48 |

| Osteoporosis | 3 (4%) | 29 (8%) | 0.27 |

| Heart Problem | 17 (22%) | 86 (25%) | 0.70 |

| Stomach Problem | 21 (27%) | 66 (19%) | 0.15 |

| Bowel or Intestinal Problem | 10 (13%) | 40 (12%) | 0.88 |

| Depression | 6 (8%) | 41 (12%) | 0.41 |

| Joint Problem | 41 (53%) | 186 (54%) | 0.98 |

| Other¶ | 28 (36%) | 117 (34%) | 0.78 |

| Time since most recent episode > 2 years | 22 (29%) | 63 (18%) | 0.06 |

| SF-36 scores, mean(SD)|| | |||

| Bodily Pain (BP) | 32.5 (18.8) | 30.6 (19) | 0.42 |

| Physical Functioning (PF) | 34.6 (25.1) | 31.5 (21.4) | 0.26 |

| Physical Component Summary (PCS) | 29.2 (8.5) | 29.1 (8) | 0.89 |

| Mental Component Summary (MCS) | 50.1 (11) | 48.3 (12.2) | 0.23 |

| Oswestry (ODI)** | 44.5 (18.4) | 45.5 (18) | 0.67 |

| Stenosis Frequency Index (0–24)†† | 15.1 (5.3) | 14.9 (5.6) | 0.72 |

| Stenosis Bothersome Index (0–24)‡‡ | 15.5 (5) | 15.3 (5.6) | 0.79 |

| Back Pain Bothersomeness§§ | 4.4 (1.7) | 4.1 (1.8) | 0.19 |

| Leg Pain Bothersomeness¶¶ | 4.5 (1.5) | 4.5 (1.6) | 0.72 |

| Satisfaction with symptoms - very dissatisfied | 56 (73%) | 267 (77%) | 0.47 |

| Problem getting better or worse | 0.17 | ||

| Getting better | 0 (0%) | 15 (4%) | |

| Staying about the same | 22 (29%) | 96 (28%) | |

| Getting worse | 54 (70%) | 228 (66%) | |

| Treatment preference | 0.99 | ||

| Preference for non-surg | 16 (21%) | 71 (21%) | |

| Not sure | 13 (17%) | 56 (16%) | |

| Preference for surgery | 48 (62%) | 218 (63%) | |

| Pseudoclaudication - Any | 62 (81%) | 279 (81%) | 0.93 |

| SLR or Femoral Tension | 17 (22%) | 72 (21%) | 0.94 |

| Pain radiation - any | 58 (75%) | 271 (79%) | 0.64 |

| Any Neurological Deficit | 33 (43%) | 195 (57%) | 0.04 |

| Reflexes - Asymmetric Depressed | 18 (23%) | 91 (26%) | 0.69 |

| Sensory - Asymmetric Decrease | 19 (25%) | 108 (31%) | 0.31 |

| Motor - Asymmetric Weakness | 20 (26%) | 90 (26%) | 0.90 |

| Stenosis Levels | |||

| L2–L3 | 22 (29%) | 106 (31%) | 0.81 |

| L3–L4 | 52 (68%) | 234 (68%) | 0.93 |

| L4–L5 | 68 (88%) | 321 (93%) | 0.24 |

| L5-S1 | 24 (31%) | 85 (25%) | 0.30 |

| Stenotic Levels (Mod/Severe) | 0.31 | ||

| None | 1 (1%) | 5 (1%) | |

| One | 25 (32%) | 124 (36%) | |

| Two | 37 (48%) | 128 (37%) | |

| Three+ | 14 (18%) | 88 (26%) | |

| Stenosis Locations | |||

| Central | 68 (88%) | 297 (86%) | 0.74 |

| Lateral Recess | 63 (82%) | 280 (81%) | 0.98 |

| Neuroforamen | 21 (27%) | 106 (31%) | 0.65 |

| Stenosis Severity | 0.24 | ||

| Mild | 1 (1%) | 5 (1%) | |

| Moderate | 38 (49%) | 134 (39%) | |

| Severe | 38 (49%) | 206 (60%) | |

| Taking antidepressants | 1 (1%) | 11 (3%) | 0.60 |

Seventy-seven patients underwent revision surgery within 8 years of index surgery. The 77 patients who had revision surgery and 345 patients who had no revision surgery had at least one follow-up through 8 years and were included in the current study. The index surgery is within 8 years of enrollment.

Race or ethnic group was self-assessed. Whites and blacks could be either Hispanic or non-Hispanic.

This category includes patients who were receiving or had applications pending for workers compensation, Social Security compensation, or other compensation.

Body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Other = problems related to stroke, cancer, fibromyalgia, CFS, PTSD, alcohol, drug dependency, lung, liver, kidney, blood vessel, nervous system, migraine or anxiety.

T∂he SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score indicating less severe symptoms.

The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Stenosis Frequency Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Stenosis Bothersomeness Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Low Back Pain Bothersomeness Scale ranges from 0 to 6, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms

The Leg Pain Bothersomeness Scale ranges from 0 to 6, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The association of baseline demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and health status measures with revision surgery was investigated via chi-square tests for categorical variables and a t-test for continuous variables.

Table 2.

Operative treatments, complications and events.

| SPS | Had Revision Surgery (n=74)* |

No Revision Surgery (n=343) |

p-value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure | 0.84 | ||

| Decompression only | 63 (89%) | 294 (88%) | |

| Non-instrumented fusion | 3 (4%) | 19 (6%) | |

| Instrumented fusion | 5 (7%) | 20 (6%) | |

| Multi-level fusion | 2 (3%) | 15 (4%) | 0.74 |

| Decompression level | |||

| L2–L3 | 28 (39%) | 121 (36%) | 0.73 |

| L3–L4 | 52 (72%) | 234 (69%) | 0.74 |

| L4–L5 | 66 (92%) | 313 (93%) | 0.91 |

| L5-S1 | 26 (36%) | 131 (39%) | 0.76 |

| Levels decompressed | 0.71 | ||

| 0 | 2 (3%) | 6 (2%) | |

| 1 | 14 (19%) | 80 (23%) | |

| 2 | 26 (35%) | 103 (30%) | |

| 3+ | 32 (43%) | 154 (45%) | |

| Operation time, minutes (SD) | 123.6 (63.4) | 130.1 (66.4) | 0.45 |

| Blood loss, cc (SD) | 253.2 (263) | 323.5 (426.1) | 0.18 |

| Blood Replacement | |||

| Intraoperative replacement | 6 (8%) | 34 (10%) | 0.82 |

| Post-operative transfusion | 4 (6%) | 17 (5%) | 0.92 |

| Length of hospital stay, dsys (SD) | 2.7 (1.9) | 3.3 (2.5) | 0.058 |

| Intraoperative complications§ | |||

| Dural tear/ spinal fluid leak | 4 (5%) | 34 (10%) | 0.33 |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 4 (1%) | 0.79 |

| None | 69 (95%) | 304 (89%) | 0.22 |

| Postoperative complications/events¶ | |||

| Wound hematoma | 1 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 0.79 |

| Wound infection | 3 (4%) | 6 (2%) | 0.41 |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 24 (7%) | 0.041 |

| None | 65 (90%) | 294 (86%) | 0.49 |

Surgical information was available for 74 revision surgery patients and 343 no revision surgery patients. Specific procedure information was available on 71 revision surgery and 333 no revision surgery patients.

None of the following were reported: aspiration, nerve root injury, operation at wrong level, vascular injury.

Any reported complications up to 8 weeks post operation. None of the following were reported: bone graft complication, CSF leak, nerve root injury, paralysis, cauda equina injury, wound dehiscence, pseudarthrosis.

The association of operative treatments, complications and events with revision surgery was investigated via chi-square tests for categorical variables and a t-test for continuous variables.

Figure 1.

CONSORT-style diagram of enrollment, randomization, and follow-up of study participants with spinal stenosis. The values for surgery, withdrawal, and death are cumulative over 8 years.

Surgical treatment

Of the 417 patients who had surgery data, 88% underwent decompression alone, 5% non-instrumented fusion, and 6% instrumented fusion. At eight-year follow-up, the reoperation rate was 18% (n=77). Of these patients, 32 underwent reoperation within 2 years (42%), 54 within 4 years (70%), and 65 within 6 years (84%). The indication for reoperation was recurrent stenosis or progressive spondylolisthesis in 52% (40/77), a complication or other reason in 15% (19/77), and a new condition in 16% (12/77). One patient was indicated for a pseudoarthrosis or fusion exploration over the eight-year period. The remaining patients had incomplete information with regard to indication for reoperation.

Of the 77 patients who underwent reoperation, 63 had complete information with regard to spinal level (as recorded in the Nurse Repeat Spine Surgery Survey). 21/63 of which had reoperation at the same level as the index operation, 29/63 had reoperation at a different level and 13/63 with reoperation level unspecified. Recurrent stenosis or progressive spondylolisthesis accounted for 11/21 (same level), 23/29 (different level), and 2/13 (unspecified) of the reoperations, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

SPS Cox’s proportional hazards model results for variables predicting time-to-reoperation.

| Variable | Estimate | Standard Error | Chi-Square | p-value | Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence interval (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.010 | 0.009 | 1.150 | 0.2835 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 |

| Gender (Female vs Male) | −0.277 | 0.242 | 1.311 | 0.2523 | 0.76 | 0.47–1.22 |

Cox’s proportional hazards model was used to explore which variables maintained significance after adjusting for other variables in the model. Variables significant at p<0.10 were candidates for inclusion in the final multivariable regression model. Final selection for the model was done using the stepwise method as implemented in SAS Release 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), which sequentially enters the most significant variable with p<0.10 and then after each entered variable removes variables that do not maintain significance at p<0.05. Age and gender were forced to be in the model.

Candidate predictor variables:

age, gender, race, education, marital status, work status, BMI, smoking status, work lift demand, hypertension, diabetes, osteoporosis, depression, heart problem, joint problem, time since most recent episode, patient’s self-assessment of health trend, patient dissatisfied with symptoms, expectation of free of pain with surgery, expectation of free of pain with nonoperative treatment, opioid use, injections, had physical therapy, taking antidepressants, taking NSAID, predominant back pain, low back pain bothersomeness scale, back pain bothersomeness scale, stenosis bothersomeness index, Oswestry disability index, bodily pain, physical function, mental component summary, physical component summary, neurogenic claudication, pain on straight-leg raising or femoral-nerve tension sign, dermatomal pain radiation, any neurologic deficit, asymmetric reflexe depression, asymmetric sensory decrease, asymmetric motor weakness, moderate or severe stenotic levels, location of stenosis, and severity of stenosis.

Laminectomy level for the index procedure was L2-L3 in 149 patients (36%), L3-L4 in 286 patients (69%), L4-L5 in 379 patients (90%), and L5-S1 in 157 patients (38%). Four percent of patients underwent a multi-level fusion and the percent of patients with zero, one, two, and three or more levels decompressed were 2%, 23%, 31%, and 45%, respectively.

Patient characteristics

Patients undergoing reoperation were less likely to have presented with any neurological deficit upon enrollment (43% vs. 57% in the no-reop group, p = 0.04). There were no other significant differences in demographic variables or incidence of comorbidities, baseline HRQOL, or baseline clinical information.

Operative outcomes

Analysis of operative treatments, complications, and adverse events revealed patients in the reoperation group had a slightly longer length of hospital stay during their index surgery though this was not statistically significant (2.7 vs 3.3 p = 0.058), (Table 2). No significant differences between the two groups were found in decompression levels, multi-level fusions, instrumentation, number of levels decompressed, operative time, blood loss, use of blood replacement, or rate of intra-operative complications.

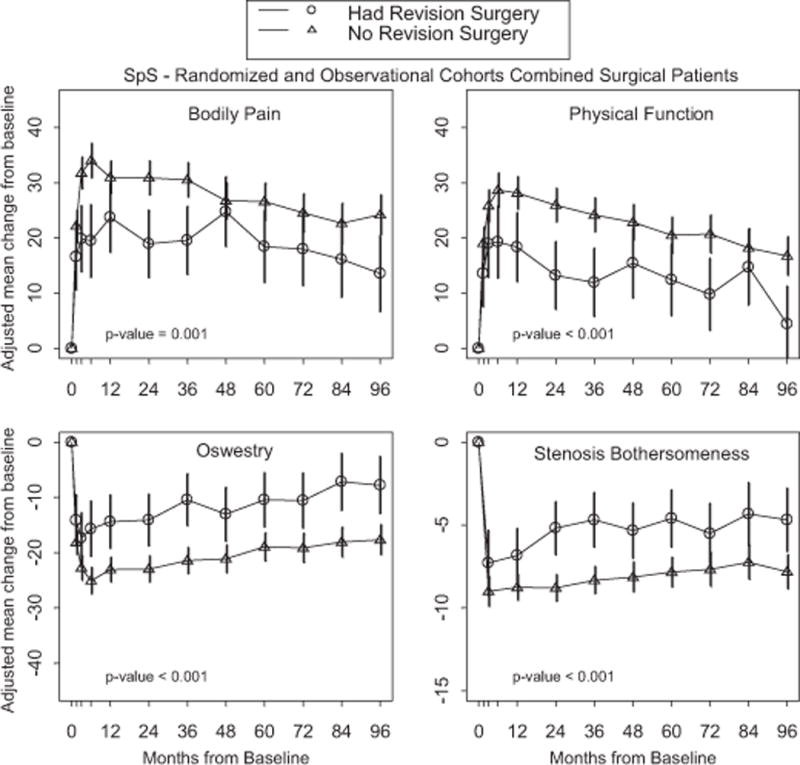

Patient reported outcomes

Mean change in patient reported outcomes scores from baseline to eight-year follow-up were better in the no reoperation group for SF-36 BP and PF, ODI, SBI, and satisfaction with symptoms and care (Table 3, Figure 2). In other words, patients who underwent a reoperation had less improvement from baseline to eight year than the no-reoperation group.

Table 3.

Change scores and their differences (“Had revision surgery” minus “No revision surgery”) of average over 8 years area under curve for long-term SF-36 scores, Oswestry Disability Index scores, Sciatica Bothersomeness Index scores, and Very/somewhat Satisfied with Symptoms, according to status of revision surgery.*

| SPS | Mean Change in Score Compared with Baseline (Standard Error) or Percent | Difference† (95% Confidence interval) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Had revision surgery (n=77) |

No revision surgery (n=345) |

|||

| SF-36 Bodily Pain (BP) (SE)†† | 19.1 (2.2) | 27.3 (1.1) | −8.1 (−13, −3.2) | 0.001 |

| SF-36 Physical Function (PF) (SE)†† | 13.2 (2.4) | 22.4 (1.1) | −9.2 (−14.4, −4) | <0.001 |

| Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) (SE) ‡ | −11.4 (1.8) | −20.4 (0.9) | 9.1 (5.2, 13) | <0.001 |

| Stenosis Bothersomeness Index (SE)§ | −5.1 (0.6) | −7.9 (0.3) | 2.8 (1.5, 4.1) | <0.001 |

| Very/somewhat satisfied with symptoms (%) | 48.9 | 59.6 | −10.6 (−19.7, −1.5) | 0.022 |

Scores are adjusted for age, gender, compensation, baseline score of stenosis bothersomeness index, income, smoking status, duration of most recent episode, treatment preference, diabetes, joint problem, stomach comorbidity, baseline score (for SF-36 and ODI), and center.

Difference is the difference between the revision surgery and no revision surgery mean change from baseline (“Had revision surgery” minus “No revision surgery”).

The SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score indicating less severe symptoms.

The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Stenosis Bothersomeness index range from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

Figure 2.

Primary outcomes over time with area under curve p-value that compares average 8 years mean change from baseline between revision surgery group and no revision surgery group.

Cox Proportional Hazards Model

In the multivariate analysis, no patient factors, comorbidities, clinical findings, operative variables or radiographic findings were found to be statistically significant predictors of reoperation (all p > 0.05), (Table 4).

Table 4.

SPS Levels of Reoperation Surgery.*

| All Reoperation Patients With Complete Information (n=63) |

Reoperation at the Same Level as Index Operation (n=21) |

Reoperation at a Different Level than the Index Operation (n=29) |

Reoperation Levels Unspecified (n=13) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrent stenosis or progressive spondylolisthesis | 36 | 11 | 23 | 2 |

| Pseudoarthrosis/fusion exploration | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Complication | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Other | 13 | 4 | 2 | 7 |

| New condition | 10 | 6 | 4 | 0 |

Reoperation at the Same Level as Index Operation: One or more reoperation level(s) are in the index surgery level (L23, L34, L45, L5S1), and no reoperation levels are not in the index surgery level.

Reoperation at a Different Level than the Index Operation: At least one reoperation level is not in the index surgery level.

Reoperation Levels Unspecified: No level information reported in the repeat spine surgery (RSS) dataset.

DISCUSSION

Although the SPORT trial data demonstrated significant benefits of surgical intervention for the treatment of SpS, a better understanding of risk factors for poor outcomes is critical for use during the decision making process and counseling for surgery. This subanalysis of the SPORT SpS data offers unique insight into clinical factors associated with reoperation after surgical treatment of spinal stenosis. Specifically, this study investigated the incidence and causes of reoperation, risk factors for reoperation, and differences in outcomes in patients undergoing reoperation versus patients not undergoing reoperation by eight year follow up. This study represents the first investigation of its kind, using a large prospective database focused on lumbar stenosis that excludes instability or deformity cases.

The reoperation rate for patients with SpS at eight years post-operatively was 18% in this cohort, with 70% of these occurring within the first four years. As found in other studies, the causes for reoperation in the first four years were inadequate decompression, disease progression, technical errors, adjacent segment disease, persistent pain, and post-operative complications1,2,14,15. In 52% of cases, the reason for reoperation was documented as recurrent stenosis or progressive spondylolisthesis, which may occur as a result of disease progression or related to surgical technique10,16. In our study, a reoperation was most likely due to progressive degenerative changes or recurrent stenosis at the index or adjacent levels, though some were a result of complications or a new condition.

Whether or not arthrodesis augments or blunts the effects of surgical decompression has also not been substantiated5,10,13,15,17. In our study, surgery included arthrodesis in 12% of patients and there was no difference in reoperation rates when comparing fusion versus non-fusion procedures. Stratification by surgical technique showed similar reoperation rates for decompression alone, non-instrumented fusion, or instrumented fusion, (p < 0.84). Though these findings are consistent with prior reports, there were insufficient numbers of patients with fusion to power further analyses. Selection bias may also explain our findings as more severe cases may have been selected for fusion15. Previous studies have shown similar findings, though most reports include heterogenous data including patients with other spinal pathology.5,13,18

In contrast with prior studies, multi-level laminectomy (>2 levels) was not associated with an increased risk of reoperation (p < 0.71), though our sample size was small.11,12 Fox et al correlated the development of post-operative instability in patients undergoing a decompression of greater than one level, though there was no correlation between patient outcomes and late instability following spinal decompression alone19. Several other reports have also questioned this debate of whether arthrodesis is indicated when extensive decompressions are performed and demonstrated no correlation between patient outcomes and decompression with arthrodesis versus decompression alone10,18,19. In a study by Deyo et al, patients undergoing decompression alone versus arthrodesis at four-year follow up had similar reoperation rates, though they included patients with spondylolisthesis, scoliosis and previous lumbar surgery.11 Martin et al, found higher reoperation rates in patients undergoing fusion compared with decompression alone (21.5% versus 18.8%, p < 0.008), though they also included a heterogenous patient sample.10

Risk factors

Interestingly, smoking, depression, workman’s compensation, other medical comorbidities, and obesity were not associated with an increased risk for reoperation. This result differs from other reports that have shown increasing rates of reoperation with specific comorbidities.5,10,13,20 Patients undergoing re-operation were less likely to have presented with a neurologic deficit at enrollment, which underscores the importance of patient selection and that the presence of neurologic deficits may help identify more appropriate surgical candidates. To our knowledge, this is the first report of these specific findings, though the exact significance remains to be substantiated, and the presence of neurological deficit was not significant in the multivariate prediction model.

Patient outcomes

As expected, the patient reported pain and functional outcomes at eight years were more favorable for patients who did not require a reoperation. Patients going on to have a reoperation had less improvement in patient outcomes scores. Other studies have shown similar findings with worse outcomes scores reported in patients that required multiple lumbar spine operations. In this time of a changing healthcare climate, decreasing reoperation rates through a better understanding of risk factors and surgical indications will enhance patient care and long-term patient outcomes.

Limitations of our study: The relatively small sample size of patients whom underwent reoperation was a limitation to this sub-analysis (n = 77) and there was a small degree of heterogeneity in the surgical techniques. That being said, this cohort is larger and more homogenous, with longer follow-up than found in other published works. The high drop out rate with any long term study can also confound the study findings as patients with worse outcomes may seek treatment elsewhere or not at all, and patients doing well following surgical or nonsurgical intervention may also be less likely to return for follow-up.

CONCLUSION

This subanalysis reports mid-term reoperation rates, risk factors and outcomes of surgically treated patients from the lumbar spinal stenosis (SpS) arm of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT). In this study patients with any neurological deficit upon enrollment were less likely to undergo a subsequent reoperation. To our surprise, patient comorbidities and socioeconomic factors did not correlate with higher reoperation rates. Additionally, patient reported outcomes at eight years were more favorable for patients who did not undergo a reoperation. These findings further support the role of surgical intervention in the treatment paradigm for SpS. The overall low reoperation rate in this trial reflects the fact that this study represented a homogenous group of patients with lumbar spinal stenosis without degenerative spondylolisthesis, or degenerative scoliosis. With strict adherence to these patient selection criteria, surgeons may achieve similar results for their patients.

Acknowledgments

The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical device(s)/drug(s). No funds were received in support of this work.

Relevant financial activities outside the submitted work: board membership, consultancy, grants, payment for lectures, royalties, stocks, travel/accommodations/meeting expenses.

Footnotes

Level of Evidence: 2

References

- 1.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis four-year results of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial. Spine. 2010;35(14):1329–1338. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e0f04d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical therapy for lumbar spinal stenosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(8):794–810. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinstein J, Birkmeyer J. The Dartmouth atlas of musculoskeletal health care. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association; 2000. p. 60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Olson P, Bronner KK, Fisher ES, Morgan MTS. United States trends and regional variations in lumbar spine surgery: 1992–2003. Spine. 2006;31(23):2707. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000248132.15231.fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atlas SJ, Keller RB, Robson D, Deyo RA, Singer DE. Surgical and nonsurgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis: four-year outcomes from the maine lumbar spine study. Spine. 2000;25(5):556–562. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200003010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boden SD, Davis D, Dina T, Patronas N, Wiesel S. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 1990;72(3):403–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;331(2):69–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407143310201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rampersaud YR, Lewis SJ, Davey JR, Gandhi R, Mahomed NN. Comparative outcomes and cost-utility after surgical treatment of focal lumbar spinal stenosis compared with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee-part 1: long-term change in health-related quality of life. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2014 Feb 1;14(2):234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rampersaud YR, Tso P, Walker KR, et al. Comparative outcomes and cost-utility following surgical treatment of focal lumbar spinal stenosis compared with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: part 2-estimated lifetime incremental cost-utility ratios. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2014 Feb 1;14(2):244–254. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin BI, Mirza SK, Comstock BA, Gray DT, Kreuter W, Deyo RA. Reoperation rates following lumbar spine surgery and the influence of spinal fusion procedures. Spine. 2007;32(3):382–387. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000254104.55716.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deyo RA, Ciol MA, Cherkin DC, Loeser JD, Bigos SJ. Lumbar spinal fusion: a cohort study of complications, reoperations, and resource use in the Medicare population. Spine. 1993;18(11):1463–1470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deyo RA, Gray DT, Kreuter W, Mirza S, Martin BI. United States trends in lumbar fusion surgery for degenerative conditions. Spine. 2005;30(12):1441–1445. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000166503.37969.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atlas SJ, Deyo RA, Keller RB, et al. The Maine Lumbar Spine Study, Part III: 1-year outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 1996;21(15):1787–1794. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199608010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hazard RG. Failed back surgery syndrome: surgical and nonsurgical approaches. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2006;443:228–232. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000200230.46071.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radcliff K, Curry P, Hilibrand A, et al. Risk for adjacent segment and same segment reoperation after surgery for lumbar stenosis: a subgroup analysis of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013 Apr 1;38(7):531–539. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31827c99f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomé C, Zevgaridis D, Leheta O, et al. Outcome after less-invasive decompression of lumbar spinal stenosis: a randomized comparison of unilateral laminotomy, bilateral laminotomy, and laminectomy. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. 2005;3(2):129–141. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.3.2.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghogawala Z, Benzel EC, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. Prospective outcomes evaluation after decompression with or without instrumented fusion for lumbar stenosis and degenerative Grade I spondylolisthesis. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. 2004;1(3):267–272. doi: 10.3171/spi.2004.1.3.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischgrund JS, Mackay M, Herkowitz HN, Brower R, Montgomery DM, Kurz LT. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis: a prospective, randomized study comparing decompressive laminectomy and arthrodesis with and without spinal instrumentation. Spine-Hagerstown. 1997;22(24):2807–2812. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199712150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox MW, Onofrio BM, Hanssen AD. Clinical outcomes and radiological instability following decompressive lumbar laminectomy for degenerative spinal stenosis: a comparison of patients undergoing concomitant arthrodesis versus decompression alone. Journal of neurosurgery. 1996;85(5):793–802. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.5.0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freedman MK, Hilibrand AS, Blood EA, et al. The impact of diabetes on the outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical treatment of patients in the spine patient outcomes research trial. Spine. 2011;36(4):290–307. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ef9d8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]