Abstract

Animals’ long-term survival is dependent on their ability to sense, filter and respond to their environment at multiple timescales. For example, during development, animals integrate environmental information, which can then modulate adult behavior and developmental trajectory. The neural and molecular mechanisms that underlie these changes are poorly understood. C. elegans is a powerful model organism to study such mechanisms; however, conventional plate-based culturing techniques are limited in their ability to consistently control and modulate an animal’s environmental conditions. To address this need, we developed a microfluidics-based experimental platform capable of long-term culture of a population of developing C. elegans covering the L1 larval stage to adulthood, while achieving spatial consistency and temporal control of their environment. To prevent bacterial accumulation and maintain optimal flow characteristics and nutrient consistency over the operational period of over one hundred and fifty hours, several features of the microfluidic system and the peripheral equipment were optimized. By manipulating food and pheromone exposure over several days, we were able to demonstrate environmental-dependent changes to growth rate and entry to dauer, an alternative developmental state. We envision this system to be useful in studying the mechanisms underlying long timescale changes to behavior and development in response to environmental changes.

Introduction

Early experiences can affect an animal’s development and behavior over an entire lifespan. For example, familial function and childhood adversity in humans are linked to altered adult HPA stress response and an increased risk for multiple forms of psychopathology1. The effects of early experiences on animal development and behavior, however, are difficult to interrogate in human and other complex organisms due to the length of developmental and reproductive timespan and lack of experimental tractability.

Due to their short reproductive lifespan (~3 days at 22°C), experimental tractability, and shared genetic mechanisms with humans, C. elegans are a useful model organism for studying environmental impacts on development2. Using a small, experimentally mapped nervous system, they can sense, integrate and respond to a variety of environmental cues using both short-term behavior and long-term developmental trajectories3–8. For example, Jin et. al. demonstrated that exposure to pathogenic bacteria in the first larval stage results in imprinted aversion to pathogenic bacterial odors that persists throughout adulthood4. Developmental plasticity can also be studied in C. elegans through the propensity for larvae to enter the dauer stage, a resilient and long-living alternative diapause state. Animals enter dauer when they predict an inhospitable environment for future reproduction using food, pheromone, and temperature cues9. Pheromones also regulate C. elegans reproduction, lifespan, and behaviour, which can vary among individual strains of C. elegans.10–17 Standard culture techniques on agar plates are limited in two main aspects necessary to investigate environmental influence on developmental decisions: 1) maintenance of a temporally and spatially consistent food source and pheromone concentration, and 2) the potential to manipulate such conditions throughout animals’ development with high temporal resolution.

On a standard plate culture, animals are continuously depleting their bacteria food source while at the same time releasing pheromones, feces and cuticles18–21. Thus, while plates are initially created with defined food and pheromone concentrations, the animals experience a time-dependent level of these stimuli over the time course of their development. In addition, bacteria are not homogenously distributed on plate: a higher concentration of bacteria exists on the outer border than the center of the food ‘lawn’ and parts of the plate lack bacteria altogether. This inhomogeneity creates a gradient of chemical attractants and repellents released by the bacteria. Further, because the bacteria are alive and respiring, a strong spatial oxygen gradient is created (15–21%) across the entirety of the plate22, 23. The difficulty in controlling spatial inhomogeneity and time-changing concentration of food and other released factors leads to a large source of potential confounding experimental factors. Moreover, in natural environments, the change in environmental condition over time (dC/dt) might be especially relevant for predicting future conditions, so gaining temporal control over food and other stimuli is also desirable. However, changing experimental conditions on plates requires tedious transfer of animals from one plate to another. If performed at high frequency, transferring animals could also potentially be physiologically disturbing. In order to limit the number of confounding factors and improve the control over larvae’s developmental experience, a different experimental platform is desirable.

Over the past decade, microfluidics has been used to develop tools for investigating worm behaviour24, reproduction25, and lifespan26 as well as chemical screening27, selective illumination28, laser microsurgery29 and automated imaging and sorting for forward genetic screens30–32 among other applications. Recent advancements has allowed researchers to grow and analyze behavior of developing animals in micro-fabricated agar chambers33 and compartmentalized glass wells34 with limited ability to modulate environmental factors and maintain consistency on extended timescales. Although a chip-gel hybrid microfluidic system has been developed for long-term development, it is limited in its operational complexity in active waste and debris removal and its low-population throughput of eight animals per device35. Similarly, the recent droplet based system was designed to modulate environment on an individual animal basis, which also increases system complexity and is not necessarily suited for population-scale assays36. One major difficulty is in preventing bacterial aggregation and contamination while maintaining optimal fluid flow rate, spatial profile, and consistency for the extended duration of animal development (over 100 hours). In addition, the design of the system needs to prevent the smallest larvae from escaping while flexible enough to accommodate the growth of the organisms.

Here, we developed a platform that addresses these challenges and maintains defined and consistent flow characteristics for over 100 hours. Using video recording, we quantify animals’ movement speed and growth rate in these conditions. As a proof of principle, we used this system to quantify these features in different food concentrations and crude pheromone levels. We show that animals can form dauers in these devices in response to crude pheromones, and the onset of population divergence in the dauer decision manifests in movement differences prior to any observed growth rate or morphological differences.

Methods

Device fabrication

PDMS devices were fabricated using standard multi-layer soft lithography techniques37. Three different masks were drawn with AutoCAD: the barrier flow paths, the remaining chambers and the herringbone mixer structures. SU8-2005, SU8-2050 and SU8-2025 (MicroChem) were spin-coated on the same wafer to the heights of 5 μm, 75 μm, and 25 μm, respectively. Transparency mask features were transferred to the SU-8 coated wafer through standard UV photolithography. The wafers were then treated with tridecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrooctyl-1-trichlorosilane (UCT Specialties, LLC) to facilitate the release of PDMS from the mold. PDMS (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning) was prepared by thoroughly mixing 10:1 ratio of base polymer to cross-linker ratio and degassing the mixture in a vacuum chamber for an hour. PDMS was poured onto the master and cured overnight at 90°C. After curing, the PDMS was removed from the master, cut, and shaped into its final form. Inlet and outlet access channels were punched with 18 gauge needles. The PDMS devices were plasma treated (PDC-32G plasma cleaner) and bonded onto glass coverslips.

C. elegans strains, culture, and media preparation

C. elegans strains used in the studies were the reference wildtype strain (N2) and QZ120 daf-2(e1368). All strains were cultured on Nematode Growth Medium (NGM) plates seeded with OP50 strain of Escherichia coli and maintained at 20°C using established culturing protocol2. To synchronize worms, eggs were obtained from gravid adult hermaphrodites by treatment with bleach solution containing 1% NaOCl and 0.1 M NaOH. The eggs were hatched in S-medium buffer overnight, washed and suspended in S-medium buffer containing 0.01 wt% Triton X100 as a surfactant for experiments.

OP50 bacteria was inoculated overnight, centrifuged, and washed with S-medium three times before being diluted to the desired concentration. The solution was supplemented with antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin) and heat-treated at 65 C for 35 minutes. Antibiotic and heat treatment of bacterial food are used to control contamination, bacterial aggregation and biofilm formation within the device. These treatments are also done on traditional plate assays as well for similar reasons13, 38, 39. The solution was then stored at −4 C and kept for a maximum of two weeks. Immediately before use, the solution was filtered through a 5-μm syringe filter to exclude large bacterial aggregates formed during storage.

Image Processing

Thirty-second videos of animals in each chamber of the device were captured using MATLAB image acquisition toolbox at 10 frames per second. To isolate the animals, background subtraction was performed by averaging the frames of a video to provide an estimated device background, which was subtracted from all frames. Thresholding and skeletonization were then used to segment out the worm bodies and a modified version of the WormTracker Version 2.0.440 to track the animals in order to obtain behavior and size data for individual animals per time point.

Pheromone Preparation

Crude pheromone was prepared as described previously41. Briefly, N2 animals were grown on S. Basal liquid medium supplemented with OP50 E. coli on day 1 and day 10. After two weeks, the worm solution was centrifuged and filtered to obtain the supernatant. The supernatant was concentrated using a rotary evaporator and lyophilized. The solid lyophilisation product was crushed and pure pheromone was extracted using ethanol and dried using rotary evaporator. The extraction process was repeated three times and resuspended in ethanol and stored in −20°C in 1 ml aliquots.

Each batch was tested on N2 worms to determine the reference concentration necessary to achieve 90% dauer arrest in 24-well plates supplemented with 0.45 OD of OP50 bacteria.

Experimental setup

Devices were first degassed at 10 psi for 30 minutes. To ensure constant OD exposure over time, bacterial adhesion to the tubing was allowed to reach steady-state, by flowing bacteria suspension through the tubing network for four hours prior. Worms were then loaded into 3-ml syringes with S-media and injected into the desired chambers. After loading, the devices were secured above the temperature controlled surface that also acted as a mirror for dark-field imaging and maintained at 25°C for the duration of the experiment. The pinch valves were installed in the bypass channel and programmed for 10-second pulses of high flow rate every 40 minutes in order to agitate and dissipate potential bacterial aggregation.

Results and Discussion

Platform Design and Operation

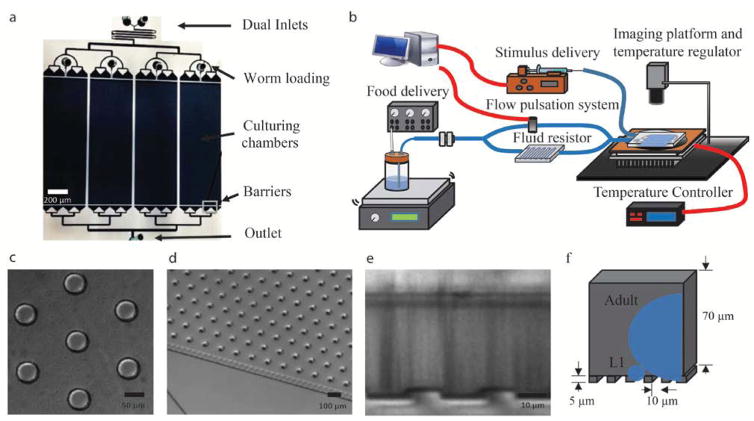

The size of an animal varies tremendously as it grows: at the L1 stage, an animal has a diameter and body length of ~12 μm and ~200 μm, respectively, whereas at adulthood, an animal has a diameter and body length of 65 μm and 1 mm. This variation poses several challenges for device design. First, in order to retain all animals for the duration of their development, the fluid entrance gates must be smaller than the L1’s body size while simultaneously large enough to allow bacteria to flow through without clogging (Fig. 1a). Second, the chamber’s pillar geometry design needs to be flexible enough to allow animals of all sizes to to move (Fig. 1c–d). Third, the natural adhesive properties of bacteria render the device prone to clogging across the 150 hours of continuous operation, which would influence not only image quality, but also flow properties within the system. These challenges were addressed with several features both on and off device.

Figure 1. Microfluidic System overview.

a) Overview of PDMS device. b) System overview: Custom-built regulator box provides positive pressure for bacterial delivery, flow delivery network and pulsation system maintains consistent flow rate, syringe pump with programmable stimulus control, and dark-field imaging setup with custom built thermoelectric temperature regulator. Red lines depict electrical connections and blue lines depict fluid connections. d) Micrographs of geometrically optimized pillars found in culturing chambers that allow for free-movement of all animal stages. e) and f) Cross-section of the device depicted using a micrograph (e) or and a schematic (f) illustrating the barriers used to constrain the animals in the device while allowing bacterial cells to flow through. Approximate size of cross-sections of initial larval stage (L1) and reproductive adults depicted in blue.

On-device features include a geometrically optimized pillar chamber (Fig. 1c), multidimensional barrier design (Fig. 1e–f) and parallel chambers (Fig. 1a). Pillars have been previously used to facilitate crawling motion, but are designed for a specific worm size in device24, 42. We chose pillar size (50-μm diameter) and spacing (120-μm) that maximized the ability of animals to move within the device at all stages (Fig. 1c). L1s were unable to ‘crawl’ in the device due to their short body length but could ‘swim’ by pushing off the pillars. Animals of various sizes moving within the pillar chamber are shown in Supplementary Video 1. These pillars serve an additional purpose of preventing convective flow from pushing the animals downstream and forming local microenvironments. Animals were restricted in the chamber using barriers up- and downstream of the chambers constructed with a two-layer fabrication technique to confine the flow entrance both in width and in height (Fig. 1e–f). An array of 5 μm × 10 μm sized openings is positioned upstream and downstream of the chamber, which serves the purpose of being small enough to prevent the L1 from escaping while large enough to reduce bacterial accumulation.

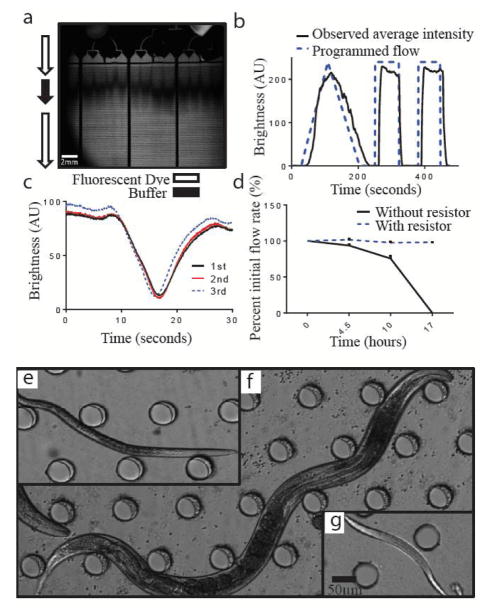

In addition to the on-chip filters, we also integrated 5-μm mesh filters into the tubing’s off-device to filter out bacterial aggregates larger than 5-μm. However, even with these measures, over time, as more aggregates accumulate within the filter, the resistance of these filters increases as well, leading to a time-dependent decrease in the systems flow rate (Fig. 2d). This problem is solved by the addition of a fluidic resistor device upstream to the culturing chamber and increasing the driving pressure proportionally to keep a consistent flow rate (Fig. 1b). The resistance of the resistor chip is several hundred times greater than that of the system alone (eqn. 1), thereby making the overall flow rate less sensitive to the resistance increase from the bacteria filters. Equations 1 to 3 shows the general concept of this resistance buffering strategy. Without the resistor (eqn. 2), the approximate increase in the resistance of the filter over time is approximately at the same magnitude to the resistance of the whole system, which decreases overall flow rate. However, with the resistor (eqn. 3), the increase in filter resistance is much less impactful to the overall resistance of the system, therefore keeping the flow rate more consistent over time (Fig. 2d). In order to remove any potential bacterial settling in the chamber, we periodically (once per hour, 10 seconds each) bypass our high resistance device to cause a transient increase in system flow rate that forces any remaining bacteria accumulated in the device to flush through.

Figure 2. Device characterization.

a) Dark field image of a pulse of buffer between fluorescent dye propagating through the device. Dark shadow in the flow distribution channel is from the attached connectors. b) Dye brightness in artificial units over time demonstrating the buffer flow in the device matches intended programmed flow. c) Dye brightness in artificial units demonstrating consistency between the three behavioral arenas d) Flow rate over time as a percent of initial flow rate at t = 0. The flow resistor helps maintain consistent system flow rate by keeping the system resistance constant over the course of the experiment. Micrographs showing e) dauer, f) reproductive adult, or g) L1 larvae within the device. Dauer and reproductive adult developed in the device starting from L1

Our current device was divided into four chambers (5 mm × 1.5 cm × 75 μm), each capable of accommodating up to 50 animals. This allows us to culture multiple strains simultaneously on

| (eqn. 1) |

| (eqn. 2) |

| (eqn. 3) |

identical devices, which helps minimize potential batch-to-batch variation. The food media inlet is separated from stimuli inlet to allow temporal stimuli changes while keeping food flow constant. To facilitate mixing of these two inlets and temperature assimilation, a herringbone chaotic mixer is placed upstream of the chambers43.

In addition to on-device features, several pieces of peripheral equipment were added for optimal long-term culture and behavior recording. For temperature control and continuous imaging, the devices are set up above an assembly of custom-made Peltier thermoelectric temperature controller and a reflective surface for dark-field imaging (Fig. 1b). Within the food delivery network (Fig 1b), a syringe pump is used for programmed stimuli delivery while positive pressure created within glass bottles is used to delivery bacteria media at a steady flow rate of 5 μl/ml.

With an imaging and temperature control setup, food and stimulus delivery system supplemented with periodic high-flow pulsation off-device (Fig. 1b), as well as several salient on-device features, we were able to successfully in parallel culture and record behavior of multiple strains of animals with minimal bacterial accumulation for over 150 hours.

System characterization shows temporal control and flow robustness

In order to characterize and validate the system, we performed several characterization experiments using fluorescein dye and syringe pumps. First, fluid distribution within the chambers were visualized by transiently switching the flow through the device from fluorescent dye to non-fluorescent buffer and then quantifying its temporal propagation in the device (Fig. 2a). The fluorescence intensity change over time at a constant axial location in all three representative chambers (Fig. 2c) showed a small (<5 second) difference in dye front between the three chambers. For our experiments, which are on the order of days, these differences are negligible. To demonstrate the system’s temporal manipulation capability, we increased our dye concentration both linearly and step-wise, and quantified the resulting change in brightness (Fig. 2b). A delay of less than 10 seconds was observed between the time of manipulating the flow programmatically and the time a change was observed in fluorescent levels in the arena, which is a result of the delay-volume of the system (from the source to the chambers). These characterization experiments demonstrate that our system can produce sufficiently precise temporal manipulations with spatial homogeneity within the chambers for the timescales this device was designed to study (~150 hours). With this system, we were able to culture and monitor animals from L1 (Fig. 2g) until they reached dauer arrest (Fig 2e) or reproductive adulthood (Fig. 2f), depending on the environmental conditions and genetic background we assayed. As with most microfluidic devices, there is a trade-off cost associated with system complexity. The set-up and clean-up time for our experiments does take several hours; however, once its operational our system is passive and would only require simple media and filter exchange once every two days.

An animal’s natural environmental contains spatial and temporal gradients for most stimuli. Neural circuits responsible for many behaviors, such as chemotaxis44 and exploration strategies45, incorporate the change of, sensory information over time (dC/dt) in addition to the absolute concentration of the stimulus. With our platform we can explore how animals use temporal information including frequency, amplitude, rate of change, and noise to alter developmental responses.

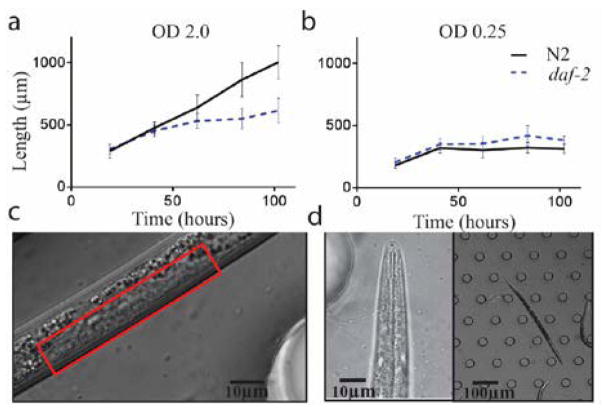

Bacterial concentration affects animals’ development and propensity to enter dauer

The growth and development of animals is dependent on their nutritional intake. A range of organisms exhibit developmental rates, final sizes, and developmental stage that are dependent on the amount of food they consume46, 47. To demonstrate the capability of this system in different environmental conditions, we sought to reproduce results from literature using two different strains and food conditions: wild-type N2 animals and daf-2 mutants (which constitutively enter the dauer stage at 25 C) in low (0.25 OD) and high (2.0 OD) bacterial density (Fig. 3). Predictably, both N2 and daf-2 mutant animals showed higher growth rate at high bacterial densities (Figure 3a and b), similar to results from Uppaluri et. al48.

Figure 3. Growth and variation at different bacteria density.

a) Mean length of N2 and daf-2 animals at high bacterial density (OD=2.0). b) Mean length of N2 and daf-2 animals at low bacterial density (OD=0.25). c) N2 animals grown at low bacterial density lack vulval invagination after 100 hours of growth, indicating L4. d) daf-2 animals at OD .25 at over 100 hours. (n = 3 experiments, >30 worms each experimental condition)

N2 animals at the low bacterial concentrations grew to a similar final size as daf-2 mutant dauers, suggesting that these animals did not develop fully into reproductive adults (Fig. 3b). Microscopy confirmed the lack of vulva invagination (Fig. 3c), indicating that the animals arrested prior to L4 development49. However, these animals are also not dauer larvae, as they did not cease pharyngeal pumping50, nor did they survive SDS treatment (Supplementary Videos 2 and 3: Dauer SDS and Larvae arrest SDS), indicating that these animals arrested at the L2, L2d or L3 stage. This is not due to a nutritional constraint as we found that daf-2 mutant animals could form dauers at this food concentration (Figure 3d and Supplementary Video 2). We suggest that the bypass of N2 animals from dauer is regulated, potentially due to the lack of pheromones in the media they are grown in. In conventional plate-based experiments, pheromones released by the animals accumulate in the plate9, 51. In our device, the fluid is continuously renewed; excretions and excess pheromones are removed from the device every 14 seconds (based upon the residence time of the liquid). It is consistent with our observations that in conventional plate experiments, pheromones released by the animals impact the results. Our device allows us to more precisely control the concentration of pheromones to more rigorously test their role in the dauer decision.

We also found that daf-2 dauers grow to a greater length in high vs. low bacterial food concentrations (Figure 3a and b). This suggests that food exposure of daf-2 animals prior to their entering dauer stage (when they cease food consumption due to closed oral orifices and constricted and non-active pharynxes9, 52) also impacts the size and potentially other aspects of the dauer animals. This platform recapitulated previously known results in N2 animal’s growth rate dependency on food concentration. We were also able to observe subtle differences in dauer formation and dauer growth rate.

Movement speed changes precede morphological changes during development in response to pheromone

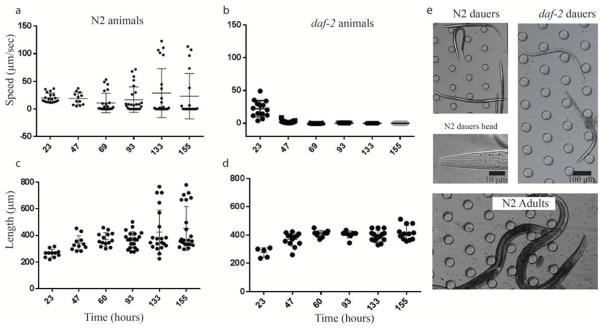

Animals entering the dauer stage undergo morphological and physiological changes such as thickening of their cuticles, blockage of orifices, cessation of pharyngeal pumping, and behavioral quiescence53. Using this platform, we were able to induce a subset of N2 animals to form dauers at low bacterial concentration (0.45) supplemented using crude pheromones. We simultaneously monitored and quantified their size and locomotion speed at six time points. As a control, we also grew daf-2 mutant animals in identical conditions. As shown in Figure 4a and 4b, while daf-2 animals initially showed a similar speed distribution as N2 animals, they entered a quiescent state at the time (47 hours) when the dauer remodelling program is initiated. For N2 animals, a bimodal distribution started to form at the 47 hour time point – suggesting the emergence of two population of animals (dauer and non-dauer animals). This population divergence response was observed in the length of the N2 animals at a much later time point (133 hours). Some N2 animals grew to a size of normal reproductive adulthood, while the remaining animals’ size remained stagnant starting at 60 hours similar to their daf-2 counterparts (Figure 4c and d). To confirm the presence of dauer animals we examined them under differential interference microscopy and identified several characteristics of dauer animals: cessation of pharyngeal pumping, blockage of orifices (Fig 4e), stereotypical body posture and size (fig. 4e). In addition, we also performed the conventional end-point SDS scoring technique and visually confirmed the presence of dauer animals.

Figure 4. Arrested development quantification.

a) Cultured with pheromone, wild type (N2) animals diverges into either dauer or adult development as evident through a) speed and c) length. b, d) daf-2 mutants are constitutively dauer and all proceeds to dauer formation at 25 C as a control. e) dauer formation was morphologically confirmed with images of N2 dauers, daf-2 dauers, and N2 adult animals. (a and b, n>35)

These results indicate dauer animals can develop on device as a response to long-term pheromone exposure. They also demonstrate that behavioral changes in animals entering the dauer stage occur before morphological changes. This locomotive and size divergence phenomenon is qualitatively reproducible in device, but we note that timing is highly sensitive to the quality of the bacterial source (Supplementary Figure 2).

Throughout development, external information is sensed and integrated via the insulin/IGF-1 and TGFβ signalling networks within the neural circuitry before a binary dauer decision is made prior to the L3 stage51. This decision then propagates throughout the body via steroid hormone signalling pathways in order to synchronize morphological changes54. Therefore, dauer decision manifests in both short timescale neural changes as well as long timescale morphological changes. By controlling the environment larvae are exposed to and quantifying dauer response in the forms of short (movement speed) and long (morphology) timescale changes, this could potentially help us understand the underlying mechanisms of dauer decision and the dynamics of the signalling pathways at play. In addition, the neuroendocrine signalling pathway was found to be evolutionary conserved in controlling many parasitic nematodes’ infectious stage. Understanding the mechanisms that govern the use of environmental information for developmental decisions and the dynamics at which these changes are manifested can be important in potentially engineering new therapeutics for nematode infections.

Conclusion

Due to the inherent temporal and spatial variation in the C. elegans’ natural environment55, animals need to sense and integrate not only the content and the amount of stimuli present, but the temporal dynamics as well. Our platform has achieved consistent and precise environmental control in culturing animals from L1 to adults or dauer animals. We have introduced various on- and off-device features in the system that allowed us to overcome several major obstacles. The major features include: 1) barriers that contains animals of all sizes but prevent clogging due to bacterial aggregates; 2) peripheral equipment and operational schemes that enables us to maintain consistent environmental conditions and flow properties for over 150 hours; 3) lastly, optimized pillar geometry that allows movement of all animals. This system is unique in that it combines full control of temperature, food and stimuli concentration, as well as temporal delivery dynamics for the duration of animals’ development. In addition, we were able to quantify not only their developmental trajectory but the associated dynamic behavioral response as well.

Besides using this platform for post-embryonic developmental research of how C. elegans use environmental pheromone information to produce short and long-time scale responses, we envision this platform can use useful for a range of other research topics. For example, to emphasize the flexibility of the behavior arena for most stages of animals, we can investigate the locomotive dynamics of developmental lethargy, where it is important to look at natural and unperturbed behavior during developmental transitions. Moreover, using the system’s capability for long-term developmental culturing with precise environmental control, we can also envision this system being used for larvae chemotaxis and thermotaxis, imprinting, or screening drugs that may induce developmental responses of various time-scales.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from Georgia Tech Parker H. Petit Institute for Bioengineering and Bioscience seed grant (to PTM and HL), the US National Institutes of Health (R21AG050304 to HL and PTM, R01GM114170 to PTM, R01NS096581, R01GM088333, R21EB021676, R01GM108962 to HL), and the Ellison Medical Foundation (to PTM). We would also like to acknowledge T. Rouse, K. Le, K. E. Bates, and J. Gray for technical assistance and critical feedback.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Supplimentary information. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.McGowan PO, Sasaki A, D’Alessio AC, Dymov S, Labonte B, Szyf M, Turecki G, Meaney MJ, Labonté B, Szyf M, Turecki G, Meaney MJ. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:342–348. doi: 10.1038/nn.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stiernagle T. WormBook: the online review of C. elegans biology. 2006. pp. 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curran SP, Ruvkun G. PLoS Genetics. 2007;3:0479–0487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin X, Pokala N, Bargmann CI, Jin X, Pokala N, Bargmann CI. Cell. 2016;164:632–643. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ardiel EL, Rankin CH. Learning & memory (Cold Spring Harbor, NY) 2010;17:191–201. doi: 10.1101/lm.960510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bargmann CI. WormBook: the online review of C. elegans biology. 2006. pp. 1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reina A, Subramaniam AB, Laromaine A, Samuel ADT, Whitesides GM. 2013:8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schindler AJ, Sherwood DR. Worm. 2014;3:e979658. doi: 10.4161/21624054.2014.979658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu PJ. WormBook: the online review of C. elegans biology. 2007. pp. 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greene JS, Brown M, Dobosiewicz M, Ishida IG, Macosko EZ, Zhang X, Butcher RA, Cline DJ, McGrath PT, Bargmann CI. Nature. 2016;539:254–258. doi: 10.1038/nature19848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greene JS, Dobosiewicz M, Butcher RA, McGrath PT, Bargmann CI. eLife. 2016:5. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Large EE, Xu W, Zhao Y, Brady SC, Long L, Butcher RA, Andersen EC, McGrath PT. PLoS genetics. 2016;12:e1006219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGrath PT, Xu Y, Ailion M, Garrison JL, Butcher Ra, Bargmann CI. Nature. 2011;477:321–325. doi: 10.1038/nature10378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aprison EZ, Ruvinsky I. PLoS genetics. 2015;11:e1005729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamada K, Hirotsu T, Matsuki M, Butcher RA, Tomioka M, Ishihara T, Clardy J, Kunitomo H, Iino Y. Science. 2010;329:1647–1650. doi: 10.1126/science.1192020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi C, Runnels AM, Murphy CT. eLife. 2017:6. doi: 10.7554/eLife.23493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maures TJ, Booth LN, Benayoun BA, Izrayelit Y, Schroeder FC, Brunet A. Science. 2014;343:541–544. doi: 10.1126/science.1244160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan F, Srinivasan J, Mahanti P, Ajredini R, Durak O, Nimalendran R, Sternberg PW, Teal PE, Schroeder FC, Edison AS, Alborn HT. PloS one. 2011;6:e17804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russel S, Frand AR, Ruvkun G. Dev Biol. 2011;360:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butcher RA, Fujita M, Schroeder FC, Clardy J. Nature chemical biology. 2007;3:420–422. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagy S, Huang YC, Alkema MJ, Biron D. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17174. doi: 10.1038/srep17174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calhoun AJ, Tong A, Pokala N, Fitzpatrick JAJ, Sharpee TO, Chalasani SH. Neuron. 2015;86:428–441. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGrath PT, Rockman MV, Zimmer M, Jang H, Macosko EZ, Kruglyak L, Bargmann CI. Neuron. 2009;61:692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albrecht DR, Bargmann CI. Nature Methods. 2011;8:599–605. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kopito RB, Levine E. Lab on a chip. 2014;14:764–770. doi: 10.1039/c3lc51061a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hulme SE, Shevkoplyas SS, McGuigan AP, Apfeld J, Fontana W, Whitesides GM. Lab on a chip. 2010;10:589–597. doi: 10.1039/b919265d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung K, Zhan M, Srinivasan J, Sternberg PW, Gong E, Schroeder FC, Lu H. Lab on a chip. 2011;11:3689–3697. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20400a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee H, Kim SA, Coakley S, Mugno P, Hammarlund M, Hilliard MA, Lu H. Lab on a chip. 2014;14:4513–4522. doi: 10.1039/c4lc00789a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung K, Lu H. Lab on a chip. 2009;9:2764–2766. doi: 10.1039/b910703g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung K, Crane MM, Lu H. Nature methods. 2008;5:637–643. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crane MM, Stirman JN, Ou CY, Kurshan PT, Rehg JM, Shen K, Lu H. Nature methods. 2012;9:977–980. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.San-Miguel A, Kurshan PT, Crane MM, Zhao Y, McGrath PT, Shen K, Lu H. Nature communications. 2016;7:12990. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bringmann H. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2011;201:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu CCJ, Raizen DM, Fang-Yen C. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2014;223:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2013.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krajniak J, Lu H. Lab on a chip. 2010;10:1862–1868. doi: 10.1039/c001986k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wen H, Yu Y, Zhu G, Jiang L, Qin J. Lab on a chip. 2015;15:1905–1911. doi: 10.1039/c4lc01377h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDonald JC, Duffy DC, Anderson JR, Chiu DT, Wu H, Schueller OJ, Whitesides GM. Electrophoresis. 2000;21:27–40. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(20000101)21:1<27::AID-ELPS27>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greer EL, Brunet A. Aging cell. 2009;8:113–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00459.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muschiol D, Schroeder F, Traunspurger W. BMC ecology. 2009;9:14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6785-9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramot D, Johnson BE, Berry TL, Carnell L, Goodman MB. PloS one. 2008;3:e2208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Golden JW, Riddle DL. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1984;81:819–823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lockery SR, Lawton KJ, Doll JC, Faumont S, Coulthard SM, Thiele TR, Chronis N, McCormick KE, Goodman MB, Pruitt BL. Journal of neurophysiology. 2008;99:3136–3143. doi: 10.1152/jn.91327.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stroock AD, Dertinger SKW, Ajdari A, Mezic I, Stone Ha, Whitesides GM. Science (New York, NY) 2002;295:647–651. doi: 10.1126/science.1066238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pierce-Shimomura JT, Morse TM, Lockery SR. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1999;19:9557–9569. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09557.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calhoun AJ, Tong A, Pokala N, Fitzpatrick JA, Sharpee TO, Chalasani SH. Neuron. 2015;86:428–441. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Monaghan P. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences. 2008;363:1635–1645. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Searcy WA, Peters S, Nowicki S. Journal of Avian Biology. 2004;35:269–279. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uppaluri S, Brangwynne CP. Proceedings Biological sciences. 2015;282:20151283. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schindler AJ, Baugh LR, Sherwood DR. PLoS Genetics. 2014;10:13–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cassada RC, Russell RL. Developmental Biology. 1975;46:326–342. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fielenbach N, Antebi A. Genes & development. 2008;22:2149–2165. doi: 10.1101/gad.1701508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keane J, Avery L. Genetics. 2003;164:153–162. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gaglia MM, Kenyon C. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:7302–7314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3429-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Motola DL, Cummins CL, Rottiers V, Sharma KK, Li T, Li Y, Suino-Powell K, Xu HE, Auchus RJ, Antebi A, Mangelsdorf DJ. Cell. 2006;124:1209–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Félix MA, Braendle C. Current biology: CB. 2010;20:R965–R969. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.