Abstract

Objective

Although several studies have delineated risk factors for adolescent regular marijuana use, few studies have identified those factors that differentiate who will and will not eventually stop using marijuana during young adulthood. This study examined the extent to which adolescent risk factors, including individual attitudes, temperament, and behaviors and peer, family, and neighborhood factors, could prospectively identify which adolescence-onset monthly marijuana users (AMMU) would stop using marijuana in young adulthood and whether race moderated these associations.

Method

Data came from 503 young men who were followed annually from the first grade through mean age 20 and then re-interviewed at mean ages 26 and 29. Young men who used marijuana at least monthly at least one year between ages 14 and 17 (N = 140) were compared to their peers who had not tried marijuana by age 17 (N = 244). The former group was divided into those who used at least weekly in adulthood (N = 54) and those who did not use at all in adulthood (N = 66) and these groups were compared to each other.

Results

Logistic regression analyses indicated that all except one of the adolescent risk factors significantly differentiated AMMU from nonusers. None of the predictors differentiated those who matured out from those who used weekly in young adulthood.

Conclusions

Future research on marijuana cessation should incorporate subjective life experiences, such as reasons for using and negative consequences from use, to help identify adolescents who are at risk for problematic use in adulthood.

Keywords: Marijuana, Mature, Risk factors, Race, Cessation

1. Introduction

Marijuana is the most widely used illicit drug in the U.S., with 22.2 million past month users aged 12 and older (8.4% of the population; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2015). Adolescence-onset persistent use has been linked to mental health problems, such as psychosis and cognitive impairment (Meier et al., 2012; Volkow, Baler, Compton, & Weiss, 2014), respiratory problems (Moore, Augustson, Moser, & Budney, 2005; Tashkin, 2013), and lower educational and occupational achievement (Ellickson, Martino, & Collins, 2004; Fergusson & Bowden, 2008; Green & Ensminger, 2006). Nonetheless, results have been inconsistent across studies (e.g., Bechtold, Simpson, White, Loeber, & Pardini, 2015; White, Bechtold, Loeber, & Pardini, 2015) and some studies have noted positive benefits of use among adults (see Caulkins, Hawken, Kilmer, & Kleiman, 2012).

Whereas earlier age of onset has been identified as a critical predictor of later substance use-related problems (e.g., Chou & Pickering, 1992; Grant & Dawson, 1997), Labouvie and White (2002) argued that it is necessary to differentiate adolescence-onset use that terminates in young adulthood from adolescence-onset use that is followed by a persistent pattern of relatively frequent use into adulthood. They found that the former pattern was linked to social risk factors (e.g., friends’ use), which they argued are often encountered by normally socialized adolescents. The latter pattern was linked to social and individual risk factors, such as behavioral disinhibition (see also Pedersen & Skrondal, 1998). Thus, adolescent risk factors may differ depending on specific patterns of later use.

Although several studies have delineated risk factors associated with the development of adolescent marijuana use (e.g., Brook, Zhang, & Brook, 2011; Farhat, Simons-Morton, & Luk, 2011; Griffith-Lendering, Huijbregts, Mooijaart, Vollebergh, & Swaab, 2011; Martel et al., 2009; Rogosch, Oshri, & Cicchetti, 2010), few studies have identified factors that distinguish which youth will eventually stop using marijuana during the transition to adulthood. It is critical to differentiate adolescence-limited from continuing users because some negative effects of regular marijuana use (e.g., cognitive impairment) can rebound following periods of sustained abstinence (see Pardini et al., 2015), and cumulative exposure may be more critical to the development of long-term problems than age of onset (Labouvie & White, 2002; Meier et al., 2012). Thus, if we can identify early risk factors that increase the probability of continued use, we may be in a better position to intervene before problems develop. The current study examines whether adolescent risk factors, including individual attitudes, temperament, and behaviors and peer, family, and neighborhood factors, can prospectively identify which adolescence-onset monthly marijuana users (AMMU) will and will not stop using marijuana in young adulthood.

1.1. Previous studies

One reason for the absence of studies examining early predictors of maturing out of marijuana use is that several longitudinal studies have not followed youth long enough to identify a group that has matured out (e.g., Flory, Lynam, Milich, Leukefeld, & Clayton, 2004; Lynne-Landsman, Bradshaw, & Ialongo, 2010; Windle & Wiesner, 2004) or have not had early data on adolescent predictors (e.g., Schulenberg et al., 2005). Juon, Fothergill, Green, Doherty, and Ensminger (2011) is one of a few studies to examine early predictors of marijuana trajectories into adulthood (age 32). They found no differences between adolescence-limited and persistent marijuana users on any childhood predictors, including family background, first grade aggressive and shy behavior, academic achievement, family involvement, and parental drug rules. A serious limitation of their study was that marijuana use was dichotomized as any use, which does not differentiate low- from high-level use. Also, there were several gaps between assessments, limiting the ability to verify continuous use.

In a study that overcame several of the limitations of previous research, Epstein et al. (2015) examined trajectories of marijuana use from ages 14 to 30. They compared a group that used marijuana in adolescence but reduced their use after age 18 and stopped using by age 30 to a group that used similarly in adolescence but escalated their use in young adulthood and continued through age 30; predictors were measured at ages 10–14. The only variable that significantly differentiated the two groups was behavioral disinhibition. The two groups did not differ significantly in past-month marijuana, alcohol, or tobacco use, family and peer marijuana use, family environment, antisocial peers, neighborhood disorganization, marijuana availability, anxiety, and depression.

Whereas few adolescent predictors of maturation have been identified, several studies have shown that role changes in young adulthood (e.g., marriage, parenthood, career) are key predictors of cessation from marijuana use (e.g., Chen & Kandel, 1998; Labouvie, 1996). Nevertheless, it is critical to identify distal predictors that can foretell which adolescent marijuana users will mature out and which will continue in adulthood. Identifying such factors would help in the identification of targets for early prevention and intervention (Hayatbakhsh, Najman, Bor, O’Callaghan, & Williams, 2009).

1.2. Conceptual model

Two types of developmental cascade models have been applied to elucidate the processes through which distal risk and protective factors influence proximal drivers of substance use transitions Dodge et al., (2009; Lynne-Landsman et al., 2010; Martel et al., 2009; Masten, Desjardins, McCormick, Kuo, & Long, 2010; Rogosch et al., 2010). The first, antisocial pathways models, posit that a combination of adverse environmental factors (e.g., dysfunctional parenting) and genetically-driven temperamental features (e.g., hyperactivity/impulsivity) place youth at risk for developing antisocial behaviors and beliefs (Fergusson, Horwood, & Ridder, 2007; Martel et al., 2009; Molina & Pelham, 2003) and affiliations with delinquent peers (Marshall, Molina, & Pelham, 2003), which subsequently foster and reinforce persistent use. Similarly, harsh and abusive parenting and poor parental monitoring have been consistently associated with substance use problems in adolescence and adulthood (Cheng & Lo, 2011; Dodge et al., 2009; Fergusson, Boden, & Horwood, 2008; Rogosch et al., 2010) and this effect is partially mediated by the development of early conduct problems and affiliation with deviant peers (Chassin, Pillow, Curran, Molina, & Barrera, 1993; Dodge et al., 2009; Rogosch et al., 2010).

In contrast to risk-based approaches, prosocial involvement/bonding models emphasize factors that can protect youth from becoming intensely involved in substances over time and potentially promote later desistence (e.g., Catalano, Kosterman, Hawkins, Newcomb, & Abbott, 1996; Oetting & Donnermeyer, 1998). These models posit that positive involvement and bonding with socializing agents (e.g., community, school, family) reinforce prosocial beliefs that deter deviant behavior and affiliations with antisocial peers (Catalano et al., 1996; Haller, Handley, Chassin, & Bountress, 2010; Oetting & Donnermeyer, 1998). Consistent with this conceptualization, adolescents who are more involved in school (Cheng & Lo, 2011, Crosnoe, Erickson, & Dornbusch, 2002) and religious activities (Flory et al., 2004) tend to be protected from developing heavy and persistent substance use. Similar findings have been reported for positive parenting (Beyers, Toumbourou, Catalano, Arthur, & Hawkins, 2004; Henry, Oetting, & Slater, 2009).

1.3. Current study

This study extends prior research on adolescent predictors of maturing out of marijuana use. We focus specifically on adolescent predictors rather than young adult role changes to identify targets for early prevention and intervention. We use a sample of AMMU and compare those who matured out to those who used at least weekly in young adulthood. We selected individual and environmental risk and protective factors identified in empirical tests of the antisocial pathways and prosocial involvement/bonding models described above, including attitudes toward marijuana and delinquency, impulsivity, depression, religiosity, school achievement, truancy, theft, violence, alcohol, tobacco and other drug use, drug dealing, peer marijuana use, caretaker monitoring, childhood maltreatment, family on welfare, and problematic neighborhood. Based on research cited in the conceptual model above, we hypothesize that all of these risk and protective factors will differentiate adolescent monthly marijuana users from nonusers. Conversely, we hypothesize that only lower impulsivity in adolescence will be related to maturing out of marijuana use (Epstein et al., 2015; Labouvie & White, 2002).

We also examine race as a moderator. Research on racial differences in prevalence of marijuana use has been mixed and generally indicates that differences depend on developmental stage and cohort (White, Loeber, & Chung, 2016). Furthermore, previous research has identified differences among black and white youth in predictors of drug use (e.g., religiosity is stronger for black than white adolescents; Wallace, Brown, Bachman, & Laveist, 2003) and in levels and exposure to risk factors (e.g., white youth are more susceptible to peer pressure than black youth; Wallace & Muroff, 2002; see also Catalano et al., 1993). Therefore, it is necessary to examine race differences in processes and predictors of maturation. Based on this research, we expect that there will be racial differences in predictors (e.g., peer use and religiosity) of nonuse versus monthly use in adolescence. Because no study that we are aware of has examined race as a moderator of adolescent predictors of marijuana use cessation, we treat this aspect of the study as exploratory.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Design and sample

The data come from the youngest cohort of the Pittsburgh Youth Study (PYS). The PYS is a prospective study of the development of delinquency, substance use, and mental health problems, which recruited boys from the Pittsburgh public schools in 1987–1988. Only boys were included in the PYS due to its original focus on delinquency. Out of a pool of 1165 incoming first grade boys, 849 were randomly screened for early conduct problems. Boys who scored in the top 30% and an approximately equal number randomly selected from the remainder were selected for follow-up (N = 503). The follow-up sample did not differ significantly from the screening sample on race, family composition, and California Achievement Test reading scores (Pardini et al., 2015). The boys’ mean age at screening was 6.9 (SD = 0.5). The sample was predominately black (55.7%) and white (40.6%) boys. Most primary caregivers were biological mothers (92%). More than half of families (61.3%) were receiving public financial assistance (see Loeber, Farrington, Stouthamer-Loeber, and White (2008) for details).

After screening, youth were interviewed at 6-month intervals for 4 years and then annually for 9 years until mean age 20 (SD = 0.61). The completion rate averaged above 90% across the 14 years of data collection. Follow-up interviews were conducted in 2006–2007, when men were mean age 26 (SD = 1.0; N = 427), and in 2009–2010, when men were mean age 29 (SD = 1.1; N = 402). Eleven men were deceased before the age 26 follow-up (2.2%) and a total of 16 men were deceased before the age 29 assessment (3.2% of initial sample). Of the men who were alive at the time of the age 26 follow-up (N = 492), 89.8% provided data at either the age 26 or 29 assessment (N = 442). Men who did not provide data at either follow-up (including those who died) did not differ from men who participated in at least one young adult interview on average marijuana frequency between ages 14 and 17, race, and all except one of the 18 adolescent risk factors (ps > 0.05). Compared to men who completed at least one young adult interview, men who missed both scored higher in impulsivity (p = 0.02).

Parental consent and child assent were obtained until the men turned 18. After that consent was obtained from the men. All study procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Marijuana use

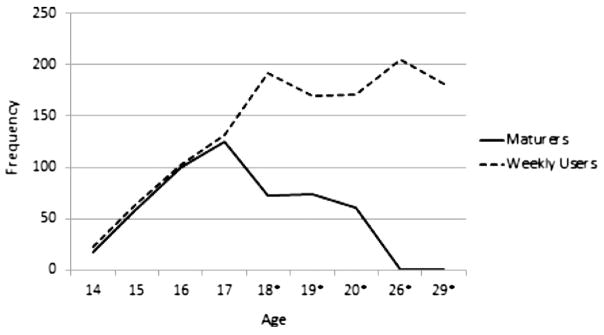

At each assessment, participants reported the number of times they used marijuana in the last year. Youth who reported no marijuana use by age 17 were included in the nonusing group (N = 244). Individuals who used marijuana at least monthly during at least one year between ages 14 and 17 were identified as AMMU (N = 140). (Those youth who used some marijuana during adolescence but less than monthly were excluded from this study; N = 85; results from analyses comparing them to the adolescent nonusers and monthly users are available in Supplemental Table 1.) Young adult marijuana use was calculated as the maximum frequency of use at ages 26 and 29. The group of AMMU was subdivided into two groups: (1) those who used at least weekly in young adulthood (adult weekly users; N = 54); and (2) those who did not use at all in young adulthood (maturers; N = 66). (Twenty AMMU who used some marijuana in young adulthood but engaged in less than weekly use were eliminated from analyses comparing adult weekly users to maturers. Of the men who did not use marijuana in adolescence, 67.3% were not using in young adulthood, 14.8% were using less than weekly, and 17.9% at least weekly.) There were no significant differences between adult weekly users and maturers in frequency of marijuana use at any age between 14 and 17; however, beginning at age 18, the adult weekly users reported significantly more frequent annual use than the maturers (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Unlogged frequency of marijuana use from adolescence into adulthood for adolescence-onset marijuana users who matured out in adulthood (maturers) and those who used weekly in young adulthood (weekly users). Notes: *t-test indicates a significant difference between groups at p < 0.001.

2.2.2. Race

Race was coded white (= 1), black (= 2), and other (= 3). The other category was eliminated in the race moderation analyses because of their small number.

2.2.3. Risk factors

Most individual and environmental risk and protective factors were measured annually from mean ages 14–17 (exceptions described below). All risk and protective factors were coded so that higher scores equal greater risk. Details on these measures, including distributional properties and reliabilities, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of the unstandardized risk factors (N = 384).

| Risk factors | Description | Mean (SD) | Range | Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual attitudes | ||||

| Toward marijuana | Youth report on a 4-point scale (0 = very wrong to 3 = not wrong at all) averaged across ages 14–17 | 0.65 (0.66) | 0–2.75 | N/A |

| Toward delinquency | Youth report on a 4-point scale (0 = very wrong to 3 = not wrong at all) added across 11 types of delinquency at each assessment and then averaged across ages 14–17 | 6.43 (4.70) | 0–32 | 0.91 |

| Individual temperament | ||||

| Impulsivity | A symptom was considered present if either the parent or teacher reported it, and the total score was the number of symptoms present; scores were averaged across ages 14–16 | 8.27 (3.63) | 0–14 | 0.88 |

| Depressed mood | Youth report, averaged across ages 14–17 | 2.20 (2.59) | 0–17.5 | 0.84 |

| Individual behaviors | ||||

| Low religiosity | Youth report across 13 symptoms, averaged across ages 14–17 | 1.17 (0.56) | 0–2 | |

| Poor school achievement | Teacher report on a 4-point scale (1 = above average to 4 = failing) summed across four subjects (reading, spelling, math and writing); averaged across ages 14–16 | 2.57 (0.84) | 1–4 | N/A |

| Truancy | Proportion of assessments with any truancy between ages 14–17 as reported by either the caretaker or youth | 0.51 (0.38) | 0–1 | N/A |

| Theft | Any moderate or serious theft offense (e.g., larceny, burglary, auto theft) between age 14–17 based on youth self-report and official criminal conviction records | 0.40 (0.49) | 0–1 | N/A |

| Violence | Any moderate or serious violent offense (e.g., gang fighting, forcible robbery, assault) between ages 14–17 based on youth self-report and official criminal conviction records | 0.33 (0.47) | 0–1 | N/A |

| Alcohol use | 4-point scale (0 = no use, 1 = less than monthly, 2 = less than weekly, and 3 = weekly or more often) based on youth self-report; highest frequency ages 14–17 | 1.13 (1.13) | 0–3 | N/A |

| Tobacco use | 3-point scale (0 = no use, 1 = less than daily, and 2 = daily) based on youth self-report; highest frequency ages 14–17 | 0.71 (0.88) | 0–2 | N/A |

| Other illicit drug use | Any use of illicit drugs besides marijuana (e.g., cocaine, LSD and nonmedical use of prescription drugs) ages 14–17 based on youth self-report | 0.08 (0.26) | 0–1 | N/A |

| Drug selling | Any dealing ages 14–17 based on youth self-report | 0.25 (0.44) | 0–1 | N/A |

| Environmental predictors | ||||

| Peer marijuana use | 5-point scale (0 = none to 4 = all) based on youth self-report averaged across ages 14–17 | 1.02 (1.07) | 0–4 | N/A |

| Low caretaker monitoring | Six items completed annually and averaged across ages 14–17 as reported by the caretaker | 7.26 (1.27) | 6–13.65 | 0.58 |

| Childhood maltreatment | Any substantiated maltreatment at ages 12 and under based on official records | 0.20 (0.40) | 0–1 | N/A |

| Family on welfare | If any family member received public assistance during ages 14–17 based on caretaker report | 0.46 (0.50) | 0–1 | N/A |

| Problematic neighborhood | 3-point scale (1 = not a problem to 3 = big problem) summed across 17 items based on caretaker report and then averaged across ages 14–17 | 25.27 (7.95) | 17–51 | 0.96 |

Notes: N/A = not applicable.

2.2.3.1. Individual attitudes

Positive attitude toward marijuana was a single item that asked youth how “wrong it is” for someone their age to use marijuana. Positive attitude toward delinquency was based on the youth’s report of how “wrong it is” for someone their age to engage in 11 types of delinquent behavior.

2.2.3.2. Individual temperament

Impulsivity included 14 symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity, and attention problems as reported by caretakers on the Child Behavioral Checklist (CBCL, Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983) and teachers on the Teacher Report Form (TRF, Edelbrock & Achenbach, 1984). Depressed mood was the number of symptoms of major depressive disorder out of 13 on the Recent Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (Costello & Angold, 1988).

2.2.3.3. Individual behaviors

Low religiosity was assessed by three questions asking how often the youth attends religious services, whether he likes going to religious activities, and whether he would choose going to a religious service over something else. Poor school achievement was the teacher’s assessment of the youth’s academic performance. Truancy was the proportion of assessments during which the boy was truant from school. Theft and violence were whether or not the youth committed any moderate or serious offense between ages 14 and 17 based on youth reports and official criminal conviction records. Alcohol use and tobacco use were the highest last-year frequency between ages 14 and 17. Other illicit drug use was coded 1 if the youth reported any use in any year between ages 14 and 17. Drug selling was coded 1 if the youth sold marijuana or other illicit drugs in any year between ages 14 and 17.

2.2.3.4. Environmental predictors

Peer marijuana use represented the proportion of friends who used marijuana. Low caretaker monitoring was assessed by six items reflecting knowledge of the child’s whereabouts. Childhood maltreatment covered any form of substantiated maltreatment that occurred by age 12 from the Allegheny County Children and Youth Services records. Welfare was coded 1 if any family member received public assistance between ages 14 and 17. Problematic neighborhood was the sum of 17 items that assessed whether certain issues were “problems” in their neighborhoods (e.g., abandoned buildings, crime). (The mean score across the 4 years reflects any potential changes in neighborhood.)

2.3. Analytic plan

Two sets of logistic regression analyses were conducted. The first compared AMMU to nonusers and the second compared AMMU who continued to use at least weekly in young adulthood to those who matured out. Risk factors were standardized and entered into separate models due to multicollinearity among factors. Because we were interested in identifying unique predictors of maturing out to inform prevention and intervention, we chose not to combine risk factors into composite scales. We repeated the second set of models (comparing adult weekly users to maturers) controlling for number of months incarcerated between mean ages 20 and 29 (based on self-report and official records) but the results did not change substantially and incarceration was not significantly related to maturing out; thus, we present the results for the models without incarceration. We tested for race interactions with risk factors for both sets of models by limiting the sample to only black and white men and adding an interaction term between race and each standardized risk factor. Due to the testing of multiple logistic regression models, a conservative Bonferroni correction factor (based on 18 risk factors) was used to determine statistical significance (p < 0.0028).

3. Results

3.1. AMMU vs. nonusers

Chi square analyses (χ2 = 6.64, df = 1, p = 0.01) indicated that black (41.7%), compared to white (28.7%), men were significantly more likely to be in the AMMU group. Table 2 shows the results for the logistic regression analyses comparing AMMU to nonusers. All of the risk factors except childhood maltreatment significantly differentiated the former from the latter group. (Maltreatment was significant [p = 0.0092] without Bonferroni correction.) No race interactions were significant based on the Bonferroni correction (although the interaction with peer marijuana use was close: p = 0.019).

Table 2.

Logistic regression results comparing adolescent monthly users to nonusers and young adult weekly users to maturers.a

| Predictor | Adolescent monthly users (N = 140) vs. nonusers (N = 244) | Adult weekly users (N = 54) vs. maturers (N = 66) |

|---|---|---|

| Individual attitudes | ||

| Positive toward marijuana | 7.13 (4.91–10.36), p < 0.0001 | 0.92 (0.63–1.35), p = 0.68 |

| Positive toward delinquency | 4.32 (3.16–5.90), p < 0.0001 | 0.81 (0.57–1.14), p = 0.22 |

| Individual temperament | ||

| Impulsivity | 1.64 (1.31–2.06), p < 0.0001 | 0.74 (0.49–1.10), p = 0.14 |

| Depressed mood | 1.51 (1.22–1.87), p < 0.0002 | 0.92 (0.66–1.27), p = 0.59 |

| Individual behaviors | ||

| Low religiosity | 1.97 (1.56–2.49), p < 0.0001 | 0.80 (0.51–1.26), p = 0.34 |

| Poor school achievement | 1.69 (1.35–2.12), p < 0.0001 | 0.95 (0.60–1.49), p = 0.81 |

| Truancy | 4.78 (3.47–6.57), p < 0.0001 | 1.09 (0.63–1.89), p = 0.76 |

| Theft | 3.44 (2.69–4.41), p < 0.0001 | 1.04 (0.70–1.55), p = 0.84 |

| Violence | 3.74 (2.92–4.80), p < 0.0001 | 0.95 (0.66–1.38), p = 0.79 |

| Alcohol frequency | 6.80 (4.78–9.69), p < 0.0001 | 1.09 (0.70–1.71), p = 0.71 |

| Tobacco frequency | 3.35 (2.62–4.28), p < 0.0001 | 1.01 (0.70–1.47), p = 0.96 |

| Other illicit drug use | 1.67 (1.33–2.11), p < 0.0001 | 1.00 (0.79–1.27), p = 1.00 |

| Drug selling | 6.86 (4.57–10.29), p < 0.0001 | 1.17 (0.84–1.62), p = 0.34 |

| Environmental predictors | ||

| Peer marijuana use | 18.26 (10.29–32.41), p < 0.0001 | 1.09 (0.73–1.63), p = 0.67 |

| Parental monitoring | 2.20 (1.71–2.83), p < 0.0001 | 1.42 (0.99–2.04), p = 0.06 |

| Childhood maltreatment | 1.96 (1.18–3.25), p < 0.0092 | 0.48 (0.21–1.10), p = 0.08 |

| Family on welfare | 3.05 (1.97–4.72), p < 0.0001 | 0.82 (0.39–1.75), p = 0.61 |

| Problematic neighborhood | 1.38 (1.12–1.70), p < 0.0022 | 1.08 (0.74–1.56), p = 0.70 |

Odds ratios presented; confidence intervals in parentheses.

3.2. Adult weekly users vs. maturers

Although more black (46.2%) than white (37.8%) men were in the adult weekly user group, the difference was not statistically significant (χ2 = 0.71, df = 1, p = 0.40). None of the risk factors significantly predicted which AMMU continued to use weekly in young adulthood and which matured out (Table 2). This finding held even without the Bonferroni correction (all ps > 0.05). No race interactions were significant (all ps > 0.05).

4. Discussion

This study attempted to identify adolescent predictors of maturing out of adolescence-onset monthly marijuana use. We selected a set of individual and environmental risk and protective factors based on a combined antisocial pathways and prosocial bonding model. Mostly consistent with our first hypothesis and the existing literature on predictors of adolescent marijuana use, all but one (childhood maltreatment) of these factors significantly differentiated AMMU from nonusers. Conversely, none differentiated those AMMU who matured out from those who continued to use at least weekly in young adulthood. This finding is mainly consistent with Epstein et al. (2015), who only found one significant adolescent predictor out of 13 that were examined, and Juon et al. (2011), who found no childhood or adolescent predictors of cessation. In the Epstein et al. (2015) study, behavioral disinhibition (measured by impulsivity, sensation seeking, and reward orientation) in early adolescence differentiated persistent marijuana users from adolescence-limited users (see also Labouvie & White, 2002). In our study, impulsivity, which encompassed impulsive, hyperactive and attention problems reported by parents and teachers, was not a significant predictor of continued weekly use into adulthood. Impulsivity is a multifaceted construct (Dawe & Loxton, 2004; Dick et al., 2010) and perhaps only certain dimensions are associated with maturing out of marijuana use. A more nuanced measure of impulsivity might have been able to differentiate these two groups.

Although we considered numerous risk factors that have differentiated adolescent marijuana users from nonusers in prior work, we may have excluded some important predictors that can differentiate those who mature out or reduce their use from those who continue to use frequently in adulthood, such as genetic factors, motivations for using, and psychopharmacological reactions to marijuana. Furthermore, it may be that developmental and role changes occur during the transition to adulthood, which are more important for maturation than adolescent risk and protective factors. Therefore, more research is needed on processes and predictors of maturation.

In terms of race, we found that race was not significantly related to maturation out of adolescent monthly marijuana use and that there were no significant race interactions in predicting maturation. Although a cross-over effect (i.e., from more white individuals using in adolescence to more black individuals using in adulthood) has been found for some drugs, findings for marijuana have been less consistent (Kandel, Schaffran, & Thomas, 2016). Based on the results for this sample, black and white young men who used marijuana at least monthly in adolescence were equally likely to continue to use at least weekly in young adulthood, although significantly more black youth than white youth used monthly during adolescence. To date little research has focused on racial differences in maturation and more research is needed. Whereas some studies have found racial differences in predictors of drug use in adolescence (e.g., Brown, Miller, & Clayton, 2004; Wallace et al., 2003; Wallace & Muroff, 2002), others report no substantive racial differences (e.g., Abbey, Jacques, Hayman, & Sobeck, 2006; Catalano et al., 1993). In this sample, consistent with the latter set of studies, similar risk factors predicted adolescent monthly marijuana use for both races.

4.1. Limitations

The size of the AMMU sample was relatively small when split into young adult weekly users and maturers, potentially limiting the power to find small but meaningful differences. Nevertheless, a sample size of about 100 is large enough to detect a small to medium effect for a single continuous predictor. Marijuana use was based on self-report of use over the past year, which could be affected by retrospective recall and social desirability. Nevertheless, studies have shown that self-reports of past-year substance use are reliable and valid (O’Malley, Bachman, & Johnston, 1983). Some youths may have received interventions, which could have influenced changes in their marijuana use. Furthermore, there was large variation in marijuana use frequency at each age during adolescence and thus daily users were combined with monthly users, which could constitute different risk profiles. Nevertheless, maturers and adult weekly users did not differ significantly in their average use during adolescence, supporting the decision to compare the two groups. Also, the sample included only men, came from only one geographical area, and was enhanced for high risk. Thus, the findings need to be replicated with women and other samples to increase generalizability.

Despite these limitations, we extended prior research in several ways: 1) prospective data were collected annually from childhood through emerging adulthood; 2) follow-ups extended into young adulthood; 3) the sample was a racially diverse, community sample and we examined whether race moderated predictors of maturation; and 4) risk factors came from multiple sources, including youths, caretakers, teachers, and official records.

4.2. Conclusion

Our set of predictors could not prospectively differentiate which AMMU would mature out and which would use weekly in young adulthood. More than half the AMMU matured out and, thus, not everyone goes on to use in adulthood. There may be natural recovery or developmental changes as well as potential negative consequences and adult role adoption that influence maturation. Future research is needed to examine these processes as well as distal risk factors (e.g., reactions to marijuana) that we did not include. Furthermore, some individuals may go on to develop problems in adulthood but others may be able to continue to use without experiencing problems and may even experience benefits (Caulkins et al., 2012). As a next step, research should try to determine which adolescents will and will not experience negative consequences from use in adolescence and adulthood so that interventions can be developed to target specific populations of adolescent marijuana users at younger ages and contribute to improving public health.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

No predictors of adolescent marijuana use differentiated those who persisted.

Race did not moderate associations between predictors and persistent use.

Black and white early monthly marijuana users are equally likely to continue.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding sources

The writing of this paper was supported by award number R01 DA034608 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Data collection was supported by grant awards to Dr. Rolf Loeber from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA011018), National Institute of Mental Health (MH079920; MH048890; MH050778), the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (86-JN-CX-0009), Pews Charitable Trusts, and the Pennsylvania State Department of Health (SAP 4100043365). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDA, the National Institutes of Health, or the U.S. Department of Justice. These funding sources had no role in the analysis or interpretation of the data, the preparation of this manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

We would like to thank Rolf Loeber, Magda Stouthamer-Loeber, and David P. Farrington for designing the initial study and sharing the data with us, and Rebecca Stallings for preparation of the data set.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Helene R. White is a member of the Board of the ABRMF/the Foundation for Alcohol Research, which is a nonprofit foundation that sponsors alcohol research. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.09.007.

Contributors

Dustin Pardini and Helene R. White are co-principal investigators on this project and conceptualized this analysis. Helene R. White conducted the analyses with support from Jordan Beardslee. Helene R. White wrote the first draft of the paper in consultation with Jordan Beardslee and Dustin Pardini. All authors have contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

References

- Abbey A, Jacques AJ, Hayman LW, Sobeck J. Predictors of early substance use among African American and Caucasian youth from urban and suburban communities. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly-Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2006;52:305–326. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Manual for the child behavior checklist and revised child behavior profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold J, Simpson T, White HR, Loeber R, Pardini D. Chronic adolescent marijuana use as a risk factor for physical and mental health problems in young adult men. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2015;29:522–563. doi: 10.1037/adb0000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyers JM, Toumbourou JW, Catalano RF, Arthur MW, Hawkins JD. A cross-national comparison of risk and protective factors for adolescent substance use: The United States and Australia. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Zhang CS, Brook DW. Antisocial behavior at age 37: Developmental trajectories of marijuana use extending from adolescence to adulthood. American Journal of Addictions. 2011;20(6):509–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TL, Miller JD, Clayton RR. The generalizability of substance use predictors across racial groups. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2004;24:274–302. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD, Krenz C, Gillmore M, Morrison D, Wells E, Abbott R. Using research to guide culturally appropriate drug abuse prevention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:804–811. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.5.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Newcomb MD, Abbott RD. Modeling the etiology of adolescent substance use: A test of the social development model. Journal of Drug Issues. 1996;26:429–455. doi: 10.1177/002204269602600207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulkins JP, Hawken A, Kilmer B, Kleiman M. Marijuana legalization: What everyone needs to know. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2015 (HHS publication no. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH series H-50). Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/

- Chassin L, Pillow DR, Curran PJ, Molina BS, Barrera MJ. Relation of parental alcoholism to early adolescent substance use: A test of three mediating mechanisms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:3–19. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Kandel DB. Predictors of cessation of marijuana use: An event history analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;50:109–121. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng TC, Lo CC. A longitudinal analysis of some risk and protective factors in marijuana use by adolescents receiving child welfare services. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33:1667–1672. [Google Scholar]

- Chou SP, Pickering RP. Early onset of drinking as a risk factor for lifetime alcohol-related problems. British Journal of Addiction. 1992;87:1199–1204. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Angold A. Scales to assess child and adolescent depression: Checklists, screens and nets. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1988;27:726–737. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198811000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, Erickson KG, Dornbusch SM. Protective functions of family relationships and school factors on the deviant behavior of adolescent boys and girls: Reducing the impact of risky friendships. Youth and Society. 2002;33:515–544. [Google Scholar]

- Dawe S, Loxton NJ. The role of impulsivity in the development of substance use and eating disorders. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2004;28:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Smith G, Olausson P, Mitchell SH, Leeman RF, O’Malley SS, Sher K. Understanding the construct of impulsivity and its relationship to alcohol use disorders. Addiction Biology. 2010;15:217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Malone PS, Lansford JE, Miller S, Pettit GS, Bates JE. A dynamic cascade model of the development of substance-use onset. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2009;74(3):1–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelbrock CS, Achenbach TM. The teacher version of the child behavior checklist. I. Boys aged six through eleven. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52:207–217. [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Martino SC, Collins RL. Marijuana use from adolescence to young adulthood: Multiple developmental trajectories and their associated outcomes. Health Psychology. 2004;23:299–307. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M, Hill KG, Nevell AM, Guttmannova K, Bailey JA, Abbott RD, … Hawkins JD. Trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence into adulthood: Environmental and individual correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2015;51:1650–1663. doi: 10.1037/dev0000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhat T, Simons-Morton B, Luk J. Psychosocial correlations of adolescent marijuana use: Variations by status of marijuana use. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:404–407. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Bowden JM. Cannabis use and later life outcomes. Addiction. 2008;103:969–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to childhood sexual and physical abuse and adjustment in early adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Conduct and attentional problems in childhood and adolescence and later substance use, abuse and dependence: Results of a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88(Suppl 1):S14–S26. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flory K, Lynam D, Milich R, Leukefeld C, Clayton R. Early adolescent through young adult alcohol and marijuana use trajectories: Early predictors, young adult outcomes, and predictive utility. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:193–213. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KM, Ensminger ME. Adult social behavioral effects of heavy adolescent marijuana use among African Americans. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1168–1178. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith-Lendering MFH, Huijbregts SCJ, Mooijaart A, Vollebergh WAM, Swaab HC. Use and development of externalizing and internalizing behaviour problems in early adolescence: A TRAILS study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;116(1–3):11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller M, Handley E, Chassin L, Bountress K. Developmental cascades: Linking adolescent substance use, affiliation with substance use promoting peers, and academic achievement to adult substance use disorders. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:899–916. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayatbakhsh MR, Najman JM, Bor W, O’Callaghan MJ, Williams GM. Multiple risk factor model predicting cannabis use and use disorders: A longitudinal study. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35:399–407. doi: 10.3109/00952990903353415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KL, Oetting ER, Slater MD. The role of attachment to family, school, and peers in adolescents’ use of alcohol: A longitudinal study of within-person and between-persons effects. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:564–572. doi: 10.1037/a0017041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juon H, Fothergill KE, Green KM, Doherty EE, Ensminger ME. Antecedents and consequences of marijuana use trajectories over the life course in an African American population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118:216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D, Schaffran C, Thomas YF. Developmental trajectories of drug use among whites and African-Americans: Evidence for the crossover hypothesis. In: Thomas YF, Price LN, editors. Drug use trajectories among minority youth. New York, NY: Springer; 2016. pp. 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie E. Maturing out of substance use: Selection and self-correction. Journal of Drug Issues. 1996;26:457–476. [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie EW, White HR. Drug sequences, age of onset, and use trajectories as predictors of drug abuse/dependence in young adulthood. In: Kandel DB, editor. Stages and pathways of involvement in drug use: Examining the gateway hypothesis. Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, White HR. Violence and serious theft: Development and prediction from childhood to adulthood. New York, NY: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lynne-Landsman SD, Bradshaw CP, Ialongo NS. Testing a developmental cascade model of adolescent substance use trajectories and young adult adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:933–948. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall MP, Molina BS, Pelham WEJ. Childhood ADHD and adolescent substance use: An examination of deviant peer group affiliation as a risk factor. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:293–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel MM, Pierce L, Nigg JT, Jester JM, Adams K, Puttler LI, … Zucker RA. Temperament pathways to childhood disruptive behavior and adolescent substance abuse: Testing a cascade model. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37(3):363–373. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9269-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Desjardins CD, McCormick CM, Kuo SIC, Long JD. The significance of childhood competence and problems for adult success in work: A developmental cascade analysis. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:679–694. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, Harrington H, Houts R, Keefe RS, … Moffitt TE. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. 2012;109:E2657–E2664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206820109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BS, Pelham WEJ. Childhood predictors of adolescent substance use in a longitudinal study of children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:497–507. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BA, Augustson EM, Moser RP, Budney AJ. Respiratory effects of marijuana and tobacco use in a US sample. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20:33–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Reliability and consistency in self-reports of drug use. International Journal of the Addictions. 1983;18:805–824. doi: 10.3109/10826088309033049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Donnermeyer JF. Primary socialization theory: The etiology of drug use and deviance. I. Substance Use & Misuse. 1998;33:995–1026. doi: 10.3109/10826089809056252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini D, White HR, Xiong S, Bechtold J, Chung T, Loeber R, Hipwell A. Unfazed or dazed and confused: Does early adolescent marijuana use cause sustained impairments in attention and academic functioning? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2015;43:1203–1217. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0012-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen W, Skrondal A. Alcohol consumption debut: Predictors and consequences. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:32–42. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogosch FA, Oshri A, Cicchetti D. From child maltreatment to adolescent cannabis abuse and dependence: A developmental cascade model. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22(4):883–897. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Merline AC, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Laetz VB. Trajectories of marijuana use during the transition to adulthood: The big picture based on national panel data. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35(2):255–279. doi: 10.1177/002204260503500203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashkin DP. Effects of marijuana smoking on the lung. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2013;10:239–247. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201212-127FR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SR. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370:2219–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Muroff JR. Preventing substance abuse among African American children and youth: Race differences in risk factor exposure and vulnerability. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2002;22:235–261. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JW, Jr, Brown TN, Bachman JG, Laveist TA. The influence of race and religion on abstinence from alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana among adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:843–848. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Bechtold J, Loeber R, Pardini D. Long-term effects of marijuana use among men: Socioeconomic, relationship, and life satisfaction outcomes in the mid-30’s. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;156:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Loeber R, Chung T. Racial differences in substance use: Using longitudinal data to fill gaps in knowledge. In: Thomas YF, Price LN, editors. Drug use trajectories among minority youth. New York, NY: Springer; 2016. pp. 123–147. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Wiesner M. Trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to young adulthood: Predictors and outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:1007–1027. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.