Abstract

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) represent an attractive class of biopharmaceutical agents, with the potential to selectively deliver potent cytotoxic agents to tumors. It is generally assumed that ADC products should preferably bind and internalize into cancer cells in order to liberate their toxic payload, but a growing body of evidence indicates that also ADCs based on non-internalizing antibodies may be potently active. In this Communication, we investigated dipeptide-based linkers (frequently used for internalizing ADC products) in the context of the non-internalizing F16 antibody, specific to a splice isoform of tenascin-C. Using monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) as potent cytotoxic drug, we observed that a single amino acid substitution of the Val-Cit dipeptide linker can substantially modulate the in vivo stability of the corresponding ADC products, as well as the anticancer activity in mice bearing the human epidermoid A431 carcinoma. In these settings, the linker based on the Val-Ala dipeptide exhibited better performances, compared to Val-Cit, Val-Lys and Val-Arg analogues. Mass spectrometric analysis revealed that the four linkers displayed not only different stability in vivo, but also differences in cleavage sites. Moreover, the absence of anticancer activity for a F16-MMAE conjugate featuring a non-cleavable linker indicated that drug release modalities, based on proteolytic degradation of the immunoglobulin moiety, cannot be exploited with non-internalizing antibodies. ADC products based on the non-internalizing F16 antibody may be useful for the treatment of several human malignancies, as the cognate antigen is abundantly expressed in the extracellular matrix of several tumors, while being virtually undetectable in most normal adult tissues.

Introduction

The use of cytotoxic agents represents the backbone of many pharmacologic approaches for the treatment of cancer. Conventional chemotherapy is often limited by the inefficient accumulation of small anti-cancer drugs into solid tumors, as evidenced by quantitative biodistribution studies and by Nuclear Medicine studies in cancer patients using radiolabeled drugs.1,2 Suboptimal pharmacokinetic profiles may damage normal organs and prevent dose escalation of chemotherapeutic agents to therapeutically active regimens. The conjugation of cytotoxic compounds to monoclonal antibodies, capable of selective accumulation at the tumor site, yields a class of promising biopharmaceutical agents, termed “antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs)”. In most cases, antibodies capable of selective binding and subsequent internalization into tumor cells are used, with the aim to release cytotoxic payloads inside the tumor site, thus improving therapeutic index.3,4,5,6 Two ADC products are available on the market for different indications (i.e., brentuximab vedotin for the treatment of certain hematological malignancies and ado-trastuzumab emtansine for the second-line treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer), while over 50 products are now under clinical evaluation.7

Brentuximab vedotin contains a linker-payload combination, featuring a valine-citrulline (Val-Cit) dipeptide moiety, a self-immolative spacer and monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) as toxic drug.8 The Val-Cit linker was chosen and optimized, in order to facilitate an intracellular cleavage by lysosomal cysteine protease (mainly cathepsin B) and the following release of MMAE, upon elimination of the p-aminobenzyl self-immolative spacer. It has recently been shown, however, that derivatives certain plasma enzymes, such as carboxylesterase 1C, can partially digest the Val-Cit linker in some ADC products, leading to drug release before the internalization process.9

Although it has been generally assumed that antibody internalization represents a strict requirement for the ADC efficacy,10,11 recent studies indicate that non-internalizing ADCs may also lead to efficacious products. Evidence of potent preclinical activity in models of cancer has been reported for non-internalizing ADC products, directed against a number of targets, including collagen IV12 and fibrin13 as well as splice variants of fibronectin14,15 and tenascin-C.16

The clinical-stage F16 antibody, specific to the alternatively-spliced A1 domain of tenascin C, does not internalize into tumor cells, but stains extracellular matrix structures in the majority of solid tumors and haematological malignancies, but not in normal tissues.17 The ability of the F16 antibody to preferentially localize to tumors has been demonstrated using radiolabeled preparations, both in preclinical models17 and in cancer patients.18 When the F16 antibody in IgG format was functionalized at a single cysteine site with a Val-Cit-MMAE linker-payload combination, the resulting non-internalizing ADC product exhibited a potent and selective anti-cancer activity in mice bearing A431 tumors and U87 gliobastomas.19

In principle, many proteolytic enzymes within the tumor microenvironment may influence the activity and selectivity of non-internalizing ADC products, featuring peptide-based linkers. In this paper, we show that the use of cleavable linkers in the IgG(F16)-MMAE conjugates represents a strict requirement for in vivo therapeutic activity. In particular, the dipeptides Val-Ala and Val-Cit exhibited a better performance compared to Val-Lys and Val-Arg for the antibody-based delivery and release of MMAE, in tumors rich in splice variants of tenascin-C.

Results and Discussion

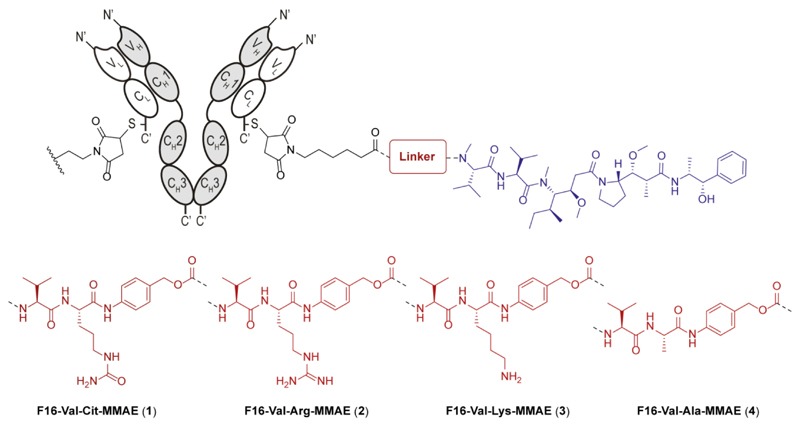

According to literature data, linkers featuring the Arg residue at the C-termini show high cleavage rates in the presence of different cysteine cathepsins, abundantly expressed at the tumor site.20 Historically, the Arg moiety has been either protected or replaced with lysine and citrulline residues, in order to improve the systemic stability.21 While this research activity led to the selection of Val-Cit dipeptide as optimal linker for internalizing ADCs, we investigated the use of Val-Cit, Val-Arg and Val-Lys sequences, as linkers for the delivery of MMAE from non-internalizing ADCs. Finally, the Val-Ala dipeptide was also studied, being used as linker in both ADCs22 and small molecule-drug conjugates.23,24 These four dipeptides were functionalized with the p-aminobenzyl carbamate (PABC) self-immolative spacer and the MMAE payload at their C-termini, according to published procedures (Figure 1).25 ADC products were prepared using an engineered derivative of the F16 antibody in human IgG1 format, bearing a reactive cysteine residue at the C-terminus of the light chain, while the other cysteine residues in the hinge region of the heavy chain had been mutated to serine.19

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the molecular structure and coupling strategy used for four F16-MMAE ADCs, incorporating the Val-Cit (1), Val-Arg (2), Val-Lys (3) and Val-Ala (4) peptide linkers.

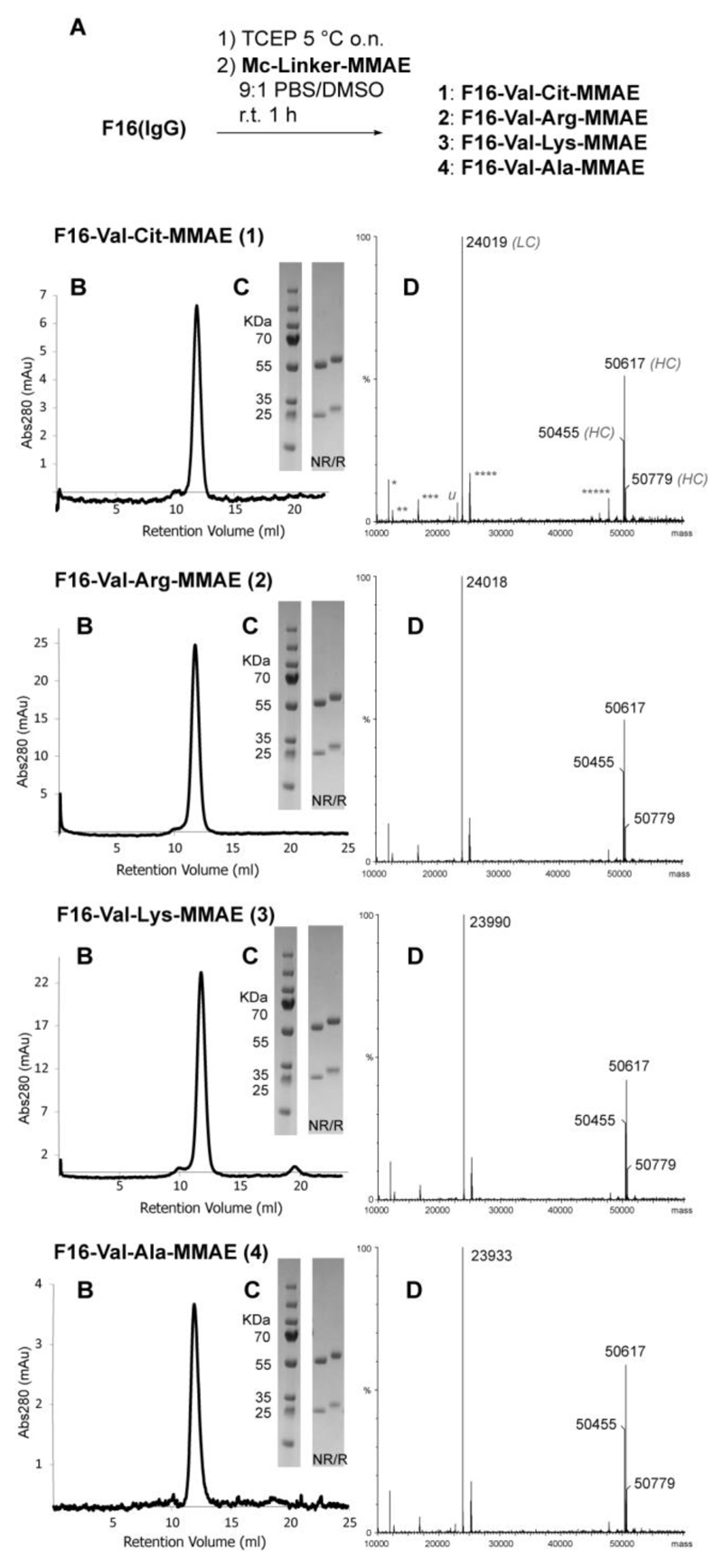

The strategy yielded ADCs with defined drug/antibody ratio (DAR) of 2, which was confirmed by mass spectrometry. Product homogeneity was also confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis and analytical size-exclusion chromatography (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Synthesis and characterization of F16-MMAE ADCs 1-4. A) Schematic representation of the conjugation protocol. TCEP: tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine. B) size-exclusion chromatography and (C) SDS-page profiles of the products in either reducing (R) and non-reducing (NR) conditions; D) deconvoluted MS spectra: antibody light chains (LC) are functionalized with Mc-Linker-MMAE modules, while the heavy chain (HC) is glycosylated, resulting in 3 main peaks of ca. 50 KDa mass (calcd. HC mass: 48489.58). Calcd. mass of the light chains of ADCs 1-4 are 24023.90, 24022.92, 23994.90 and 23937.81, respectively (4 Cys residues are considered reduced in the calculation; calcd. mass of non-conjugated LC: 22707.25). Attribution of common extra-peaks of MS spectra is indicated in ADC 1 spectrum (deconvolution artifacts *: LC/2; **: HC/4; ***: HC/3; ****: HC/2, *****: LC·2; u: trace of non-functionalized LC). Full MS spectra (raw and deconvoluted, including non-conjugated F16 antibody) are shown in the Supporting Information.

A dose escalation experiment was used to determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of the newly prepared F16-MMAE ADCs. Healthy BALB/c nude mice were treated with compounds 1-4, administered intravenously with three cycles of injections, at 12.5, 25 and 50 mg/kg doses. Daily analysis of body weights indicated that all ADC products were well tolerated, even at the highest administered dose (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Biological evaluation of F16-MMAE conjugates 1-4, featuring different cleavable dipeptide linkers: A) dose escalation study (BALB/c nude mice, n = 1 per group); B) Therapeutic activity of F16-MMAE ADCs against A431 human epidermoid carcinoma xenografted in BALB/c nude mice, after 4 administrations of ADCs (3 mg/kg every 3 days, as indicated by the arrows) and vehicle (PBS). A graph showing the percentage of body weight changes during the experiment is included in the Supporting Information. Data points represent mean tumor volume ± SEM, n = 4 per group.** indicates p < 0.01; * indicates p < 0.05.

The anticancer performance of ADCs 1-4 was investigated in a first therapy experiment in BALB/c nude mice, subcutaneously grafted with human epidermoid carcinoma cells (A431). When tumors reached 100 mm3 volume, mice were randomized and four intravenous administrations of F16-MMAE conjugates were performed following the schedule indicated in Figure 3B. While the reference ADC product F16-Val-Cit-MMAE (1) had previously shown curative effects when administered in four cycles at the dose of 7 mg/kg,19 we treated mice at a dose of 3 mg/kg, in order to identify the linker structure associated with the strongest anticancer effect at a suboptimal dose. All F16-MMAE conjugates inhibited tumor growth compared to the saline control (Figure 3B). F16-Val-Arg-MMAE (2) showed the weakest activity, whereas F16-Val-Ala-MMAE (4) exhibited the best tumor growth inhibition.

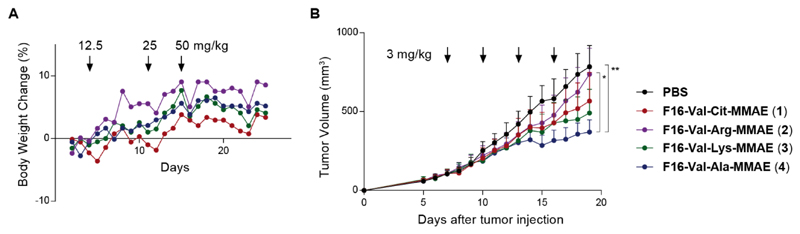

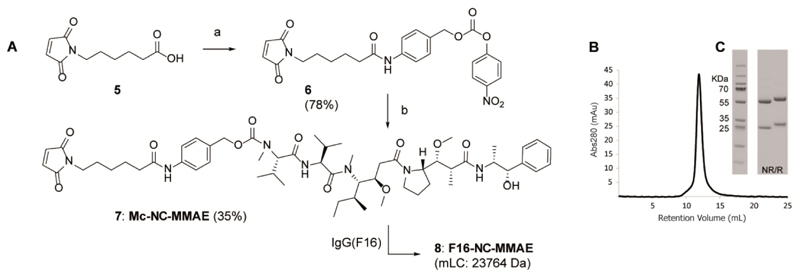

In order to formally prove that a cleavable peptide moiety was essential for activity, we prepared a fifth F16-MMAE conjugate, structurally similar to the previous conjugates but featuring a non-peptidic amide bond instead of a cleavable dipeptide. Similar non-cleavable (NC) linkers have often been used to couple different classes of cytotoxics (e.g. maytansinoids,26 calicheamicins,27 cryptophycins28 and auristatins29) to internalizing antibodies, with the aim of selectively release the toxic moiety in intracellular compartments, exploiting a proteolytic degradation of the immunoglobulin. The non-cleavable linker-MMAE module was thus synthesized by direct coupling of 6-maleimidohexanoic acid (compound 5 in Figure 4) to 4-aminobenzyl alcohol, which was then converted into the 4-nitrophenyl carbonate 6 and reacted with MMAE. The resulting structure was purified by HPLC and conjugated to the F16 mAb, leading to the new ADC F16-NC-MMAE (8, Figure 4B,C).

Figure 4.

A) Synthesis of the linker-drug module Mc-NC-MMAE (7). Reagents and Conditions: a) [1] 4-aminobenzyl alcohol, EDC·HCl, iPr2Net, CH2Cl2, r.t. overnight; [2] 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate, pyridine, THF, r.t. 4 h; b) MMAE·TFA, HOAt, iPr2Net, DMF, r.t. 48 h. B) size-exclusion chromatography and (C) SDS-page profiles of the F16-NC-MMAE ADC (8) in either reducing (R) and non-reducing (NR) conditions.

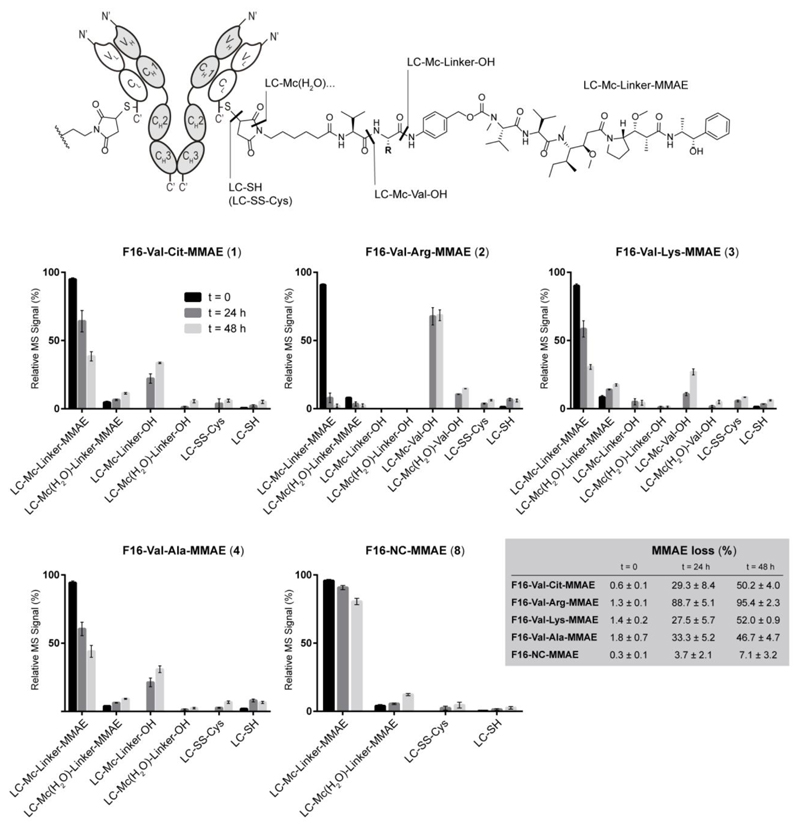

All F16-MMAE conjugates were then subjected to a comparative analysis of in vivo linker stability and metabolism. ADC products 1-4 and 8 were intravenously injected into tumor-bearing mice and animals were sacrificed after 24 and 48 hours. Blood samples were collected by heart puncture, followed by plasma purification and ADC extraction through filtration over antigen-coated resin. MS analysis of the F16 light chain revealed the progressive formation of different linker fragments, covalently bound to the protein. The metabolite occurrence was quantified by comparing the intensity of the MS signal relative to the light chain bearing the truncated fragment to the one of the intact conjugate. The results of this analysis are shown in Figure 5, together with a schematic representation of the observed metabolites.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the linker fragments observed by MS spectroscopy and presentation of their relative abundance after 24 and 48 h post injections in tumor-bearing mice (n = 2 mice/ADC). Data correspond to the ratio between the MS peak intensity of individual fragments and the sum of MS signal intensities of all detected peaks (100%). MS data of ADCs 2, 4 and 8 are shown in Figure S1. LC = light chain of F16 mAb.

With the exception of the maleimide hydrolysis (see “fragment LC-Mc(H2O)-linker-MMAE” in Figure 5) all the observed fragments are consistent with the release of MMAE payload from the antibody vehicle. As expected, the rate of MMAE loss from F16-Val-Arg-MMAE ADC was the largest one (compared to the other three dipeptide linkers), whereas the non-cleavable analogue showed an excellent in vivo stability for 48 hours.

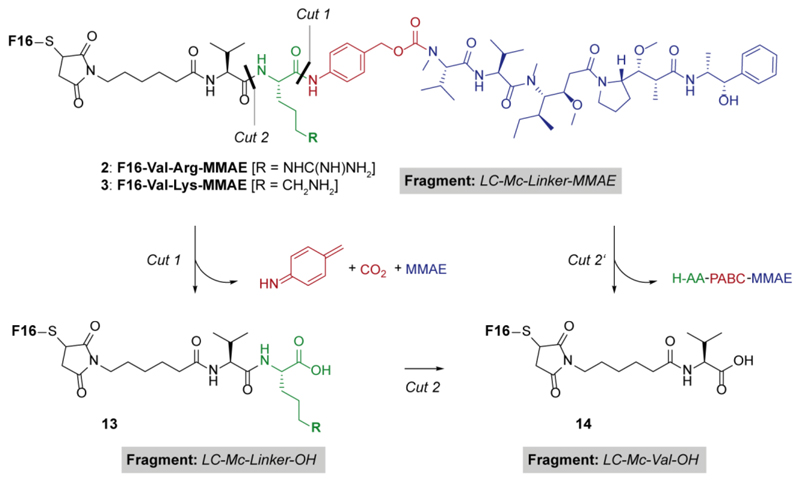

An interesting feature was observed in ADCs bearing a basic side chain in the linker (i.e., ADCs 2 and 3) and not in the Val-Cit and Val-Ala counterparts. While the linker in the latter two ADCs was only cleaved at the C-terminal position, the presence of basic residues in the other dipeptides was associated to the formation of a different main metabolite, consistent with the cleavage at the Valine C-terminus (i.e., fragment LC-Mc-Val-OH, reported as compound 14 in Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Proposed proteolytic pathways of ADCs 2 and 3, bearing amino acids with basic side chains in the linker module.

During the analysis of F16-Val-Lys-MMAE, both fragments LC-Mc-Val-OH (14) and, to a lesser extent, LC-Mc-Linker-OH (13) were detected. We interpreted the data as a result of Lysine digestion after the “traditional” dipeptide cleavage (i.e., Cut 1 followed by Cut 2’ in Scheme 1). By contrast, metabolism of F16-Val-Arg-MMAE only led to the formation of fragment LC-Mc-Val-OH (14). This data may indicate that the arginine proteolysis (Cut 2) was too fast to allow the detection of intermediate 13, even though a second pathway consisting in the direct cleavage of the dipeptide at the internal amide bond (Cut 2’) may also occur. The inclusion of ADC F16-NC-MMAE 8 in the experiment allowed the evaluation of metabolic processing in living animals of all the linker components (e.g., the maleimide moiety and the carbamate bond between the PAB spacer and MMAE) in the absence of dipeptide moieties. In particular, the maleimide hydrolysis is known to inhibit the retro-Michael step that results in the complete deconjugation of the linker-payload module (i.e., fragment LC-SH).30 The free F16 antibody was detected in blood either in the reduced form (e.g., free thiol) or oxidized by free cysteine present in circulation (i.e., fragment LC-SS-Cys), as already reported in the literature.31

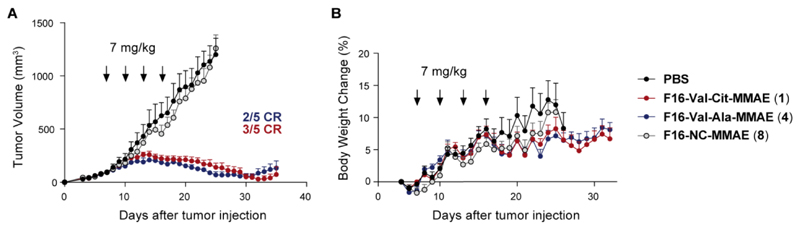

Overall, these data indicated that the ADC F16-Val-Cit-MMAE showed similar metabolic profiles and rate of MMAE loss to its analogue featuring the Val-Ala linker. The latter has been used as linker in internalizing ADC products, featuring pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) as cytotoxic payload.22 One of these therapeutics, Vadastuximab Talirine (SGN-CD33A), has recently entered Phase III trials with the CASCADE study in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML), in combination with azacitidine or decitabine. F16-MMAE ADC based on Val-Cit or Val-Ala were highly active, when used at the dose of 7 mg/kg (at which similar conjugates based on irrelevant negative control antibodies do not display detectable anti-cancer activity).19 By contrast, tumors grew rapidly in animals treated with vehicle (PBS) or with the non-cleavable F16-NC-MMAE product 8 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

A) Therapeutic activity of F16-Val-Cit-MMAE (1), F16-Val-Ala-MMAE (4) and F16-NC-MMAE (8) against A431 human epidermoid carcinoma xenografted in BALB/c nude mice, after 4 administrations of ADCs (7 mg/kg every 3 days, as indicated by the arrows) and vehicle (PBS); B) body weight changes (%) of the different treatment groups during the therapy experiment. Data points represent mean tumor volume ± SEM, n = 5 per group.

These findings are in keeping with the metabolite analysis described above, confirming that the Mc-NC-MMAE linker is stable both in circulation and in the extracellular tumor environment. Very recently, Mendelsohn and coworkers have reported that the internalizing mAb trastuzumab, functionalized with carbamate-based non-cleavable linkers, do not show anticancer activity in vitro or in vivo.32

It is likely that drug release processes and rates in the extracellular space are similar for internalizing and non-internalizing ADCs. An experimental characterization of the portion of ADC product that is internalized into tumor cells (and of the subsequent drug release kinetics) is extremely difficult to perform in vivo, especially in patients. In the context of non-internalizing ADCs, our group observed and reported an interesting correlation between the linker system and the antibody format: while ADCs bearing disulfide linkers have shown superior anticancer properties when the mAb is expressed as small immune protein (SIP),33 drug release in the extracellular space upon proteolytic action was found to be more efficient when IgG1-based mAbs are used.19

Extracellular matrix components are abundant and easily accessible in perivascular areas of tumors, which can significantly improve the accumulation and persistence of macromolecular therapeutics at the site of disease.34 Payloads released in the extracellular environment may diffuse within the tumor mass, thus potentially reaching a large number of cancer cells35, into which they would eventually internalize. The induction of tumor cell death may lead to a release of proteolytic enzymes which, in turn, could trigger additional drug release from a non-internalizing ADC product, in process which is reminiscent of a “chain reaction”. It remains to be seen, however, to which extent preclinical findings observed in tumor-bearing mice may be predictive for the protease-driven activation of ADCs in human malignancies, as enzyme concentrations could be different in the two species.

Conclusion

We have shown that ADC products, based on non-internalizing antibodies and featuring dipeptide cleavable linkers, can be potently active against cancer in vivo, while similar products based on non-cleavable linkers are not active. The linker-payload combination Val-Cit-MMAE, successfully used for the internalizing Adcetris™ ADC product, holds promise also in the context of non-internalizing tumor-targeting antibodies.

Conjugates between the IgG(F16) antibody and the potent MMAE auristatin may be considered for the treatment of various conditions, since the A1-extra domain of tenascin C is abundantly expressed in the extracellular matrix of various tumor lesions (including non-small cell lung cancer,36 head and neck37 and breast38 cancers, melanoma39, as well as certain lymphomas40 and leukemias,41 while being undetectable in most normal adult tissues.

Supporting Information

Procedures for synthesis and characterization of the tested ADC compounds, together with protocols for cell culture, in vivo experiments, statistical analysis, mass spectrometry and NMR details (PDF).

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from ETH Zürich, the Swiss National Science Foundation (Projects Nr. 310030B_163479/1, SINERGIA CRSII2_160699/1), ERC Advanced Grant “Zau-berkugel”, Kommission für Technologie und Innovation (Grant Nr. 17072.1), Bovena Foundation and Maiores Foundation.

Footnotes

ORCID

Alberto Dal Corso: 0000-0003-4437-8307

Samuele Cazzamalli: 0000-0003-0510-5664

Author Contributions

A.D.C. and S.C. contributed equally to this work.

Notes

Dario Neri is co-founder, shareholder and Board Member of Philogen, the company that owns the F16 antibody.

References

- (1).van der Veldt AA, Hendrikse NH, Smit EF, Mooijer MP, Rijnders AY, Gerritsen WR, van der Hoeven JJ, Windhorst AD, Lammertsma AA, Lubberink M. Biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of 11C-labelled docetaxel in cancer patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1950–1958. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1489-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Bosslet K, Straub R, Blumrich M, Czech J, Gerken M, Sperker B, Kroemer HK, Gesson JP, Koch M, Monneret C. Elucidation of the mechanism enabling tumor selective prodrug monotherapy. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1195–1201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Alley SC, Okeley NM, Senter PD. Antibody-drug conjugates: targeted drug delivery for cancer. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:529–537. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.06.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Gerber H-P, Koehnb FE, Abraham RT. The antibody-drug conjugate: an enabling modality for natural product-based cancer therapeutics. Nat Prod Rep. 2013;30:625–639. doi: 10.1039/c3np20113a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Chu Y-W, Polson A. Antibody-drug conjugates for the treatment of B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and leukemia. Future Oncol. 2013;9:355–368. doi: 10.2217/fon.12.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Chari RV, Miller ML, Widdison WC. Antibody-drug conjugates: an emerging concept in cancer therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:3796–3827. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).de Goeij BECG, Lambert JM. New developments for antibody-drug conjugate-based therapeutic approaches. Curr Opin Immunol. 2016;40:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Senter PD, Sievers EL. The discovery and development of brentuximab vedotin for use in relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:631–637. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Dorywalska M, Dushin R, Moine L, Farias SE, Zhou D, Navaratnam T, Lui V, Hasa-Moreno A, Casas MG, Tran TT, et al. Molecular Basis of Valine-Citrulline-PABC Linker Instability in Site-Specific ADCs and Its Mitigation by Linker Design. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:958–970. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Bander NH. Antibody-drug conjugate target selection: critical factors. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1045:29–40. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-541-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Xu S. Internalization, Trafficking, Intracellular Processing and Actions of Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Pharm Res. 2015;32:3577–3583. doi: 10.1007/s11095-015-1729-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Yasunaga M, Manabe S, Tarin D, Matsumura Y. Cancer-stroma targeting therapy by cytotoxic immunoconjugate bound to the collagen 4 network in the tumor tissue. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011;22:1776–1783. doi: 10.1021/bc200158j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Yasunaga M, Manabe S, Matsumura Y. New concept of cytotoxic immunoconjugate therapy targeting cancer-induced fibrin clots. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1396–1402. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01954.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Bernardes GJ, Casi G, Trüssel S, Hartmann I, Schwager K, Scheuermann J, Neri D. A traceless vascular-targeting antibody-drug conjugate for cancer therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:941–944. doi: 10.1002/anie.201106527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Perrino E, Steiner M, Krall N, Bernardes GJ, Pretto F, Casi G, Neri D. Curative properties of noninternalizing antibody-drug conjugates based on maytansinoids. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2569–2578. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Gébleux R, Casi G. Antibody-drug conjugates: Current status and future perspectives. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;167:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Brack SS, Silacci M, Birchler M, Neri D. Tumor-targeting properties of novel antibodies specific to the large isoform of tenascin-C. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3200–3208. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Heuveling DA, de Bree R, Vugts DJ, Huisman MC, Giovannoni L, Hoekstra OS, Leemans CR, Neri D, van Dongen GA. Phase 0 microdosing PET study using the human mini antibody F16SIP in head and neck cancer patients. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:397–401. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.111310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Gébleux R, Stringhini M, Casanova R, Soltermann A, Neri D. Non-internalizing antibody-drug conjugates display potent anti-cancer activity upon proteolytic release of monomethyl auristatin E in the sub-endothelial extracellular matrix. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:1670–1679. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Barrett AJ. Fluorimetric assays for cathepsin B and cathepsin H with methylcoumarylamide substrates. Biochem J. 1980;187:909–912. doi: 10.1042/bj1870909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Dubowchik GM, Firestone RA. Cathepsin B-sensitive dipeptide prodrugs. 1. A model study of structural requirements for efficient release of doxorubicin. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998;8:3341–3346. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00609-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Jain N, Smith SW, Ghone S, Tomczuk B. Current ADC Linker Chemistry. Pharm Res. 2015;32:3526–3540. doi: 10.1007/s11095-015-1657-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Hochdörffer K, Abu Ajaj K, Schäfer-Obodozie C, Kratz F. Development of novel bisphosphonate prodrugs of doxorubicin for targeting bone metastases that are cleaved pH dependently or by cathepsin B: synthesis, cleavage properties, and binding properties to hydroxyapatite as well as bone matrix. J Med Chem. 2012;55:7502–7515. doi: 10.1021/jm300493m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Dal Corso A, Caruso M, Belvisi L, Arosio D, Piarulli U, Albanese C, Gasparri F, Marsiglio A, Sola F, Troiani S, Valsasina B, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of RGD peptidomimetic-paclitaxel conjugates bearing lysosomally cleavable linkers. Chem Eur J. 2015;21:6921–6929. doi: 10.1002/chem.201500158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Cazzamalli S, Dal Corso A, Neri D. Linker stability influences the anti-tumor activity of acetazolamide-drug conjugates for the therapy of renal cell carcinoma. J Control Release. 2016;246:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Polson AG, Calemine-Fenaux J, Chan P, Chang W, Christensen E, Clark S, de Sauvage FJ, Eaton D, Elkins K, Elliott JM, et al. Antibody-drug conjugates for the treatment of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: target and linker-drug selection. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2358–2364. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Dijoseph JF, Dougher MM, Armellino DC, Kalyandrug L, Kunz A, Boghaert ER, Hamann PR, Damle NK. CD20-specific antibody-targeted chemotherapy of non-Hodgkin's B-cell lymphoma using calicheamicin-conjugated rituximab. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:1107–1117. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0260-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Verma VA, Pillow TH, DePalatis L, Li G, Phillips GL, Polson AG, Raab HE, Spencer S, Zheng B. The cryptophycins as potent payloads for antibody drug conjugates. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2015;25:864–868. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.12.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Dorywalska M, Strop P, Melton-Witt JA, Hasa-Moreno A, Farias SE, Galindo Casas M, Delaria K, Lui V, Poulsen K, Sutton J, et al. Site-Dependent Degradation of a Non-Cleavable Auristatin-Based Linker-Payload in Rodent Plasma and Its Effect on ADC Efficacy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Tumey LN, Rago B, Han X. In vivo biotransformations of antibody-drug conjugates. Bioanalysis. 2015;7:1649–1664. doi: 10.4155/bio.15.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Shen BQ, Xu K, Liu L, Raab H, Bhakta S, Kenrick M, Parsons-Reponte KL, Tien J, Yu SF, Mai E, et al. Conjugation site modulates the in vivo stability and therapeutic activity of antibody-drug conjugates. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:184–189. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Mendelsohn BA, Barnscher SD, Snyder JT, An Z, Dodd JM, Dugal-Tessier J. Investigation of Hydrophilic Auristatin Derivatives for Use in Antibody Drug Conjugates. Bioconjugate Chem. 2017;28:371–381. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Gébleux R, Wulhfard S, Casi G, Neri D. Antibody Format and Drug Release Rate Determine the Therapeutic Activity of Noninternalizing Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:2606–2612. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Casi G, Neri D. Noninternalizing targeted cytotoxics for cancer therapy. Mol Pharm. 2015;12:1880–1884. doi: 10.1021/mp500798y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Li F, Emmerton KK, Jonas M, Zhang X, Miyamoto JB, Setter JR, Nicholas ND, Okeley NM, Lyon RP, Benjamin DR, et al. Intracellular Released Payload Influences Potency and Bystander-Killing Effects of Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Preclinical Models. Cancer Res. 2016;76:2710–2719. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Pedretti M, Soltermann A, Arni S, Weder W, Neri D, Hillinger S. Comparative immunohistochemistry of L19 and F16 in non-small cell lung cancer and mesothelioma: two human antibodies investigated in clinical trials in patients with cancer. Lung Cancer. 2008;64:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Schwager K, Villa A, Rösli C, Neri D, Rösli-Khabas M, Moser G. A comparative immunofluorescence analysis of three clinical-stage antibodies in head and neck cancer. Head Neck Oncol. 2011;3:25. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Mårlind J, Kaspar M, Trachsel E, Sommavilla R, Hindle S, Bacci C, Giovannoni L, Neri D. Antibody-mediated delivery of interleukin-2 to the stroma of breast cancer strongly enhances the potency of chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6515–6524. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Frey K, Fiechter M, Schwager K, Belloni B, Barysch MJ, Neri D, Dummer R. Different patterns of fibronectin and tenascin-C splice variants expression in primary and metastatic melanoma lesions. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:685–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Schliemann C, Wiedmer A, Pedretti M, Szczepanowski M, Klapper W, Neri D. Three clinical-stage tumor targeting antibodies reveal differential expression of oncofetal fibronectin and tenascin-C isoforms in human lymphoma. Leuk Res. 2009;33:1718–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Gutbrodt KL, Schliemann C, Giovannoni L, Frey K, Pabst T, Klapper W, Berdel WE, Neri D. Antibody-based delivery of interleukin-2 to neovasculature has potent activity against acute myeloid leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2013 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006221. 201ra118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.