Abstract

In this study, we examined the in vivo osteogenic differentiation of human embryoid bodies (hEBs) by using an injectable in situ-forming hydrogel. A solution containing MPEG-b-(polycaprolactone-ran-polylactide) (MCL) and hEBs was easily prepared at room temperature. The MCL solution with hEBs and osteogenic factors was injected into nude mice and developed into in situ-forming hydrogels at the injection sites; these hydrogels maintained their shape even after 12 weeks in vivo, thereby indicating that the in situ-forming MCL hydrogel was a suitable scaffold for hEBs. The in vivo osteogenic differentiation was observed only in the in situ gel-forming MCL hydrogel in the presence of hEBs and osteogenic factors. In conclusion, this preliminary study suggests that hEBs and osteogenic factors embedded in an in situ-forming MCL hydrogel may provide numerous benefits as a noninvasive alternative for allogeneic tissue engineering applications.

Keywords: human embryoid bodies, in situ-forming hydrogel, osteogenic differentiation, tissue engineering

1. Introduction

Tissue engineering is a promising method for regenerating damaged tissues or organs [1] and requires the presence of suitable three-dimensional scaffolds [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Great progress has been made in the fabrication of biocompatible scaffolds, although it is prohibitively difficult to fabricate certain complicated scaffold geometries. To overcome this problem, the use of in situ-forming hydrogels as scaffolds is a promising approach for the fabrication of complicated scaffold geometries [9].

In situ-forming hydrogels are based on the concept that under physiological conditions, certain biomaterials form desired hydrogels in situ after injection as a liquid via a simple liquid-to-gel phase transition [10]. This characteristic enables hydrogels to easily trap various biologic materials such as growth factors, genes and cells. Many in situ hydrogel-forming biomaterials have been proposed, including collagen, chitosan, hyaluronate, fibrin, pluronic and various block copolymers [11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

Recently, our group reported that biodegradable methoxypoly(ethylene glycol)-b-polycaprolactone (MP) and MPEG-b-(polycaprolactone-ran-polylactide) (MCL) are potential in situ-forming hydrogels [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. MCL exhibited a biodegradation window that is adjustable from a few weeks to a few months [20,21,22]. Subsequent studies have demonstrated the potential of injectable in situ-forming MP hydrogels as in vitro and in vivo bone graft material for rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and human adipose tissue-derived stem cells [27,28].

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) possess the property of indefinite self-renewal and are derived from the inner cell mass of preimplantation embryos at the blastocyst stage [29]. Generally, the initiation of differentiation of ESCs occurs through an intermediate step involving the formation of embryoid bodies (EBs) via complex three-dimensional aggregates of ESCs [30,31]. ESCs within the aggregated EBs can undergo differentiation into all the somatic cell types, namely, the endoderm, ectoderm and mesoderm lineages [32]. Thus, EBs have the potential to serve as an omnipotent cell resource for cell therapy, including tissue engineering.

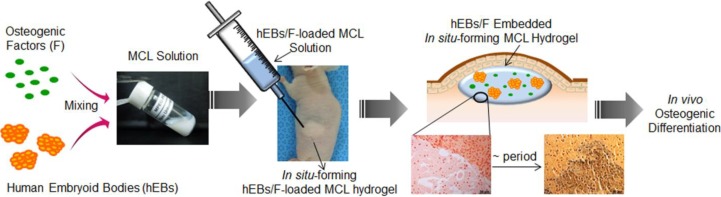

To our knowledge, the functional properties of human EBs (hEBs) incorporated into in situ-forming hydrogels have received little attention in vivo [32,33,34]. Accordingly, we sought to evaluate injectable in situ-forming hydrogels prepared from MCL, in the context of the following specific questions (Figure 1): (a) does the in situ-forming MCL hydrogel act as a suitable scaffold for hEBs in vivo? (b) does in vivo osteogenic differentiation occur in response to in situ-forming MCL hydrogels seeded with hEBs and osteogenic factors? Resolving these questions will enhance allogeneic tissue engineering applications.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of in vivo osteogenic differentiation of human embryoid bodies (hEBs) in an injectable in situ-forming MPEG-b-(polycaprolactone-ran-polylactide) MCL hydrogel with osteogenic factors.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Preparation of an Injectable in Situ-Forming Hydrogel

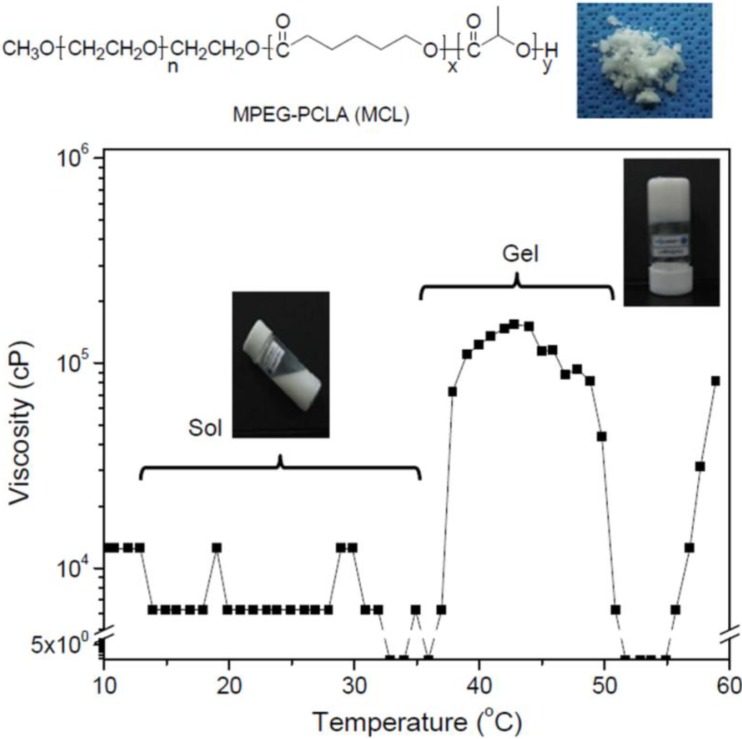

MCL (MPEG [750 g/mol]–(polycaprolactone-ran-polylactide) [PCL/PLLA, 2420/90 g/mol]) was prepared using a previously reported block copolymerization method [20]. An aqueous solution of the MCL diblock copolymer was prepared in deionized water at 80 °C at a concentration of 20 wt %. As shown in Figure 2, the MCL solution existed in a translucent emulsion-solution state at room temperature. The results obtained on analyzing the phase transition as a function of temperature demonstrated that the MCL solution exhibited low viscosity below 36 °C and became a hydrogel at 37 °C.

Figure 2.

Relationships between the viscosity and temperature of the MCL solution at 20 wt % concentration.

2.2. In Vivo Gelation

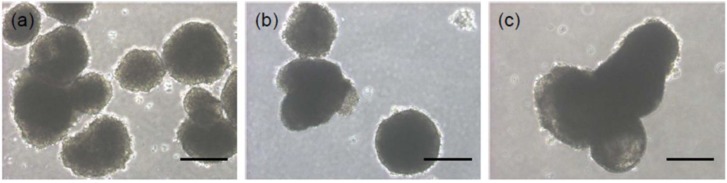

The hESC-derived EBs were cultured in suspension for 15 days (Figure 3). On day 1, the hEBs formed a spherical mass, which is the typical morphological feature of EBs; this morphological feature was maintained for 15 days. The size of hEBs increased as the culture time increased due to the spontaneous accumulation of hEBs.

Figure 3.

The morphology of hEBs at (a) 1 day; (b) 7 days; and (c) 15 days. The scale bars indicate 200 µm for the ×100 magnification.

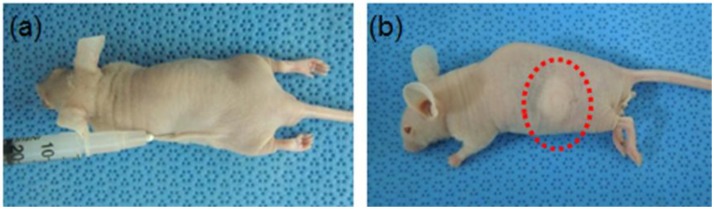

MCL containing mixtures of hEBs and osteogenic factors was easily prepared in the form of an emulsion solution. The MCL solutions containing hEBs with and without osteogenic factors were subcutaneously injected into nude mice (Figure 4a). All solutions immediately became in situ-forming hydrogels after injection, and the hydrogels were allowed to develop for 4, 8, and 12 weeks in vivo. The in situ-forming hydrogels maintained their shapes even after 12 weeks in vivo (Figure 4b). There was no inflammation at the skin surfaces of the injection sites.

Figure 4.

Image obtained (a) after the initial injection of the hEBs/F embedded in the in situ-forming MCL hydrogel; and (b) 12 weeks after hydrogel formation.

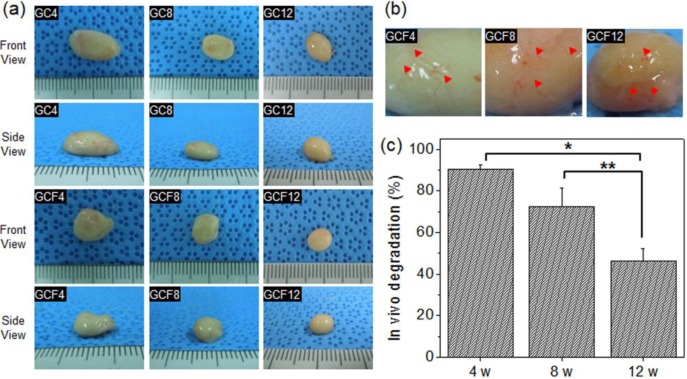

When the hydrogels were removed after 4, 8, or 12 weeks, thin fibrous capsules containing fibroblasts and vascular vessels were observed around the surfaces of the hydrogels (Figure 5a,b). This result indicated that the in situ-forming MCL hydrogel acts as a suitable scaffold substrate for hEBs in vivo. The size of the in situ-forming MCL hydrogel gradually decreased after subcutaneous injection and was 90% of the original volume at 4 weeks, 72% at 8 weeks, and 47% at 12 weeks (Figure 5c). There was no large difference between GC (MCL + hEBs) and GCF (MCL + hEBs+ osteogenic factor). This finding indicated that MCL can undergo degradation in a defined experimental period as an in situ-forming MCL hydrogel.

Figure 5.

(a) Images of the removed MCL without (GC) or with (GCF) osteogenic factors, after 4, 8, and 12 weeks. The numbers indicate the implantation time; (b) enlarged images of the removed MCL hydrogels (GCF) and (c) volume change in the in vivo excised MCL hydrogels (GCF) after 4, 8, and 12 weeks (*p < 0.001, **p < 0.05).

2.3. In Vivo Staining

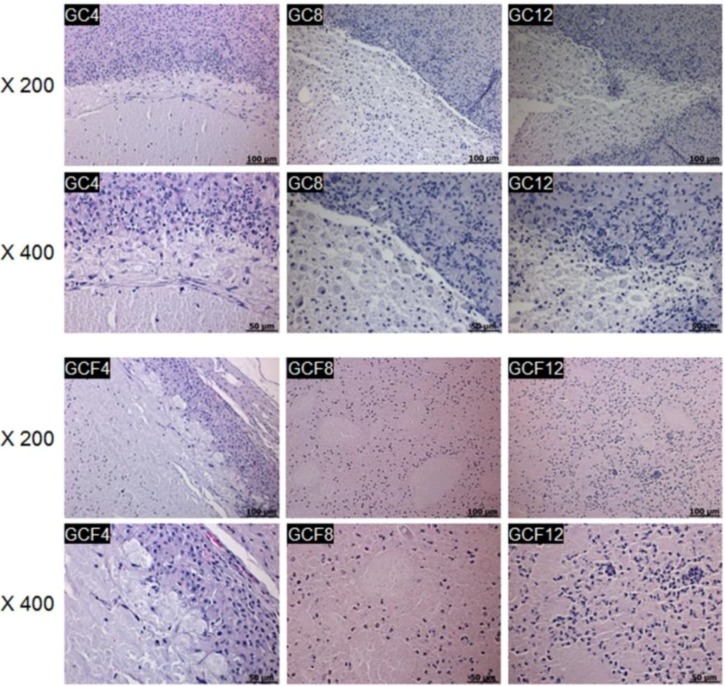

All the in situ-forming MCL hydrogels were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) at 4, 8, and 12 weeks after injection (Figure 6). The H&E-stained sections of the subcutaneous MCL hydrogels seeded with hEBs showed a number of cells interspersed in the in situ-forming MCL hydrogel. The hEBs distributed within the MCL hydrogel generally exhibited a rounded shape. The intensity of the H&E staining of the MCL hydrogel gradually decreased as the implantation time increased, probably due to the continued degradation of the MCL hydrogels.

Figure 6.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections of the MCL without (GC) or with (GCF) the osteogenic factors after 4, 8, and 12 weeks. The numbers indicate the implantation time and the scale bars indicate 100 µm for the ×400 magnification and 50 µm for the ×200 magnification.

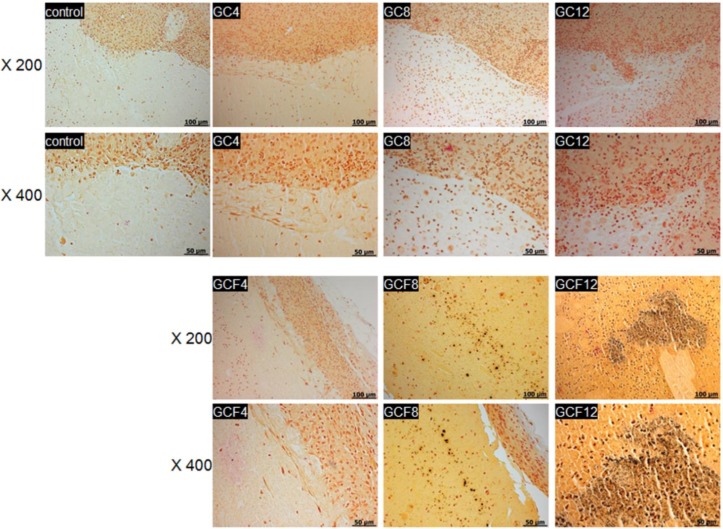

After 4, 8, and 12 weeks, histological sections of the MCL hydrogels were stained using the von Kossa staining procedure to monitor mineralized bone formation associated with osteogenic differentiation of the hEBs (Figure 7). Cross-sectional control images of MCL only without hEBs and osteogenic factors showed no detectable mineral deposition. The images of von Kossa-stained hydrogels containing only hEBs without osteogenic factors also showed no evidence of mineral deposition.

Figure 7.

von Kossa-stained sections of the MCL without (GC) and with (GCF) the osteogenic factors after 4, 8, and 12 weeks and the MCL only without hEBs and osteogenic factors as control. The numbers indicate the implantation time and the scale bars indicate 100 µm for the ×400 magnification and 50 µm for the ×200 magnification.

In contrast, mineralized bone deposits were identified in the MCL hydrogels containing both the hEBs and osteogenic factors. The colors of the von Kossa-stained images increased as the implantation time increased, even though osteoblast differentiation could be limited, due to the complete releasing of osteogenic factors within a few days. This finding indicated that the hEBs seeded in the MCL hydrogel with the osteogenic factors had undergone differentiation toward an osteoblastic phenotype.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Synthesis of MCL Diblock Copolymers

The block copolymerization used to produce MCL (750–2420:90; molecular ratio of PCL: PLLA) was performed as previously reported [20].

3.2. Viscosity Measurements

Viscosity measurements were performed using a Brookfield DV-III Ultra Viscometer equipped with a programmable thermometer and circulating baths with a programmable controller (TC-502P; Brookfield Engineering Laboratories, Middleboro, MA, USA). The viscosity of the MCL solution was determined using a T-F spindle rotating at 0.2 rpm at 10–60 °C, with temperature changes occurring in increments of 2 °C.

3.3. In Vivo Degradation of Hydrogels

For the in vivo biodegradation experiment, the MCL solutions were subcutaneously injected into the dorsal part of the nude mice that had been anesthetized with ethyl ether. The hydrogel implants were removed at 4, 8, and 12 weeks. The size of the MCL removed was assessed by measuring the diameter of the hydrogel in 3 dimensions with vernier calipers.

3.4. EB Formation

The undifferentiated human embryonic stem cell (hESC) line, SNUhES3 [35], was maintained as previously reported for research purposes, following institutional review board approval of Seoul National University Hospital and the informed consent of people undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment [36]. Briefly, hESC was cultured on a mitomycin C (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA)-treated SIM 6-thioguanune resistant-ouabain resistant (STO) (CRL-1503; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) feeder layer. The hESC colonies were dissected and replated onto a fresh feeder layer every 7 days by mechanical dissociation. A mixture of DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen, CA, USA), 20% knockout serum replacement (KO-SR; Invitrogen), 1% MEM non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen, CA, USA), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), and 4 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; Invitrogen, CA, USA) was used as the hES culture medium. In addition, the hESC culture medium was supplemented with 50 U/mL penicillin and 50 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen, CA, USA).

To induce the formation of hEBs, undifferentiated hESC colonies were cultured for 5 days. Then, the hESCs were treated with collagenase type IV (5 mg/mL; Invitrogen, CA, USA). The detached hES colonies were transferred to petri dishes to allow their aggregation. The hEBs were grown in the same culture medium as the hESCs, but without bFGF. In this study, the hEBs were cultured in suspension for three and 12 days. Each EBs were collected after centrifuge and injected as actual embryoid bodies into the hydrogel.

3.5. In Vivo Experiment

Nine nude mice (weight, 20–25 g; age, 6 weeks) were divided into 2 groups of 3 mice each and used in the animal tests for 4, 8, and 12 weeks. All the animals were treated in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Experiment Committee at the Ajou University School of Medicine. The 2 experimental groups were designated as GC (MCL + hEBs) and GCF (MCL + hEBs + osteogenic factor). The MCL was prepared as a 20 wt % solution in PBS at room temperature. The GC and GCF solutions were prepared by gently mixing all the components: a pellet containing 1 × 106 hEBs, 10% FBS, 10 mM β-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, 60 μg L-ascorbic acid, 100 nM dexamethasone, and 150 µL of MCL solution. Within 5 min of mixing, a 150 µL syringe with a 21-gauge needle was used to inject the solution into the subcutaneous dorsum of nude mice that had been anesthetized with ethyl ether. Each nude mouse was injected with only 1 aliquot of the experimental solution. The resulting hydrogels were then allowed to develop, and biopsies were performed in vivo over a 4-, 8-, or 12-week period.

3.6. Histological Analysis

At 4, 8 and 12 weeks after implantation, the mice were sacrificed, and the implants were individually dissected and removed from the subcutaneous dorsum. The tissues were immediately fixed with 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. The embedded specimens were sectioned (4 µm) along the longitudinal axis of the implant, and the sections were stained with H&E.

For the mineral nodule formation, the mineralized matrix was evaluated using the von Kossa stain. The sections of the hydrogel implants were washed with distilled water and then treated with 5% silver nitrate solution and kept for 60 min in a dark room. The excess silver nitrate solution was then washed away completely using distilled water, and the culture plate was treated with a sodium carbonate/formaldehyde solution for a few minutes to develop the color. Residual silver nitrate was neutralized with 5% sodium thiosulfate, and the samples were then washed 3 times with distilled water. The images were obtained using an Axio Imager A1 system (Carl Zeiss Microimaging GmbH, Göttingen, Germany) and analyzed with the Axiovision Release 4.8 software (Carl Zeiss Microimaging GmbH, Göttingen, Germany).

3.7. Statistical Analysis

The hydrogel implants for biodegradation were evaluated in independent experimental groups with n = 3 for each data point. All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) values. The results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison by using the SPSS software package (Version 12.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

4. Conclusions

Herein, we prepared an in situ-forming MCL hydrogel with hEBs. Our findings confirmed that the in situ-forming MCL hydrogel could be used as an in vivo substrate for hEBs and for differentiation toward an osteoblastic phenotype in nude mice. The present result suggests that hEBs seeded in situ by MCL hydrogels may provide numerous benefits as a noninvasive alternative for allogeneic tissue engineering applications. Further experiments are currently being performed on bone regeneration at bone-defect sites in animal models by using hEBs embedded in our in situ-forming MCL hydrogel. Further validations of osteogenic differentiation and mineralization are needed as future studies. In addition, further work is necessary to examine teratoma formation of hEBs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Basic Science Research Program (2013R1A2A2A04014200) and Priority Research Centers Program (2010-0028294) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) and a grant of the Korean and Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (A111539).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Muschler G.F., Nakamoto C., Griffith L.G. Engineering principles of clinical cell-based tissue engineering. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2004;86-A:1541–1558. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200407000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollister S.J., Murphy W.L. Scaffold translation: Barriers between concept and clinic. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2011;17:459–474. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2011.0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim M.S., Kim J.H., Min B.H., Chun H.J., Han D.K., Lee H.B. Polymeric scaffolds for regenerative medicine. Polym. Rev. 2011;51:23–52. doi: 10.1080/15583724.2010.537800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim M.S., Khang G., Lee H.B. Gradient polymer surfaces for biomedical applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2008;33:138–164. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gronau G., Krishnaji S.T., Kinahan M.E., Giesa T., Wong J.Y., Kaplan D.L., Buehler M.J. A review of combined experimental and computational procedures for assessing biopolymer structure-process-property relationships. Biomaterials. 2012;3:8240–8255. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peramo A. Medical implants as delivery platforms for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications. Curr. Tissue Eng. 2012;1:36–40. doi: 10.2174/2211542011201010036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walther A., Hoyer B., Springer A., Mrozik B., Hanke T., Cherif C., Pompe W., Gelinsky M. Novel textile scaffolds generated by flock technology for tissue engineering of bone and cartilage. Materials. 2012;5:540–557. doi: 10.3390/ma5030540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho S.Y., Park H.H., Jin H.J. Controlling pore size of electrospunsilk fibroin scaffold for tissue engineering. Polym.-Korea. 2012;36:651–655. doi: 10.7317/pk.2012.36.5.651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim M.S., Park S.J., Chun H.J., Kim C.H. Thermosensitive hydrogels for tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2011;8:117–123. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tian H., Tang Z., Zhuang X., Chen X., Jing X. Biodegradable synthetic polymers: Preparation, functionalization and biomedical application. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012;37:237–280. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2011.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim K.S., Lee J.H., Ahn H.H., Lee J.H., Lee J.Y., Lee B., Lee H.B., Kim M.S. The osteogenic differentiation of rat muscle-derived stem cells in vivo within in situ-forming chitosan scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4420–4428. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin Y.S., Lee J.S., Choi J.W., Min B.H., Chang J.W., Lim J.Y., Kim C.H. Transplantation of autologous chondrocytes seeded on a fibrin/hyaluronic acid composite gel into vocal fold in rabbits: Preliminary results. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2012;9:203–208. doi: 10.1007/s13770-012-0347-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baek E.J., Shin B.K., Nho Y.C., Lim Y.M., Park J.S., Park J.S., Huh K.M. Preparation of poloxamer-based hydrogels using electron beam and their evaluation for buccalmucoadhesive drug delivery. Polym.-Korea. 2012;36:182–189. doi: 10.7317/pk.2012.36.2.182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho M.H., Kim K.S., Ahn H.H., Shin Y.N., Kim M.S., Khang G., Lee B., Lee H.B. Chitosan gel as an in situ-forming scaffold for rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in vivo. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2008;14:1099–1108. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim K.S., Lee J.Y., Kang Y.M., Kim E.S., Lee B., Chun H.J., Kim J.H., Min B.H., Lee H.B., Kim M.S. Electrostatic crosslinked in situ-forming in vivo scaffold for rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2009;15:3201–3209. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J.Y., Kang Y.M., Kim E.S., Kang M.L., Lee B., Kim J.H., Min B.H., Park K., Kim M.S. In vitro and in vivo release of albumin from an electrostatically crosslinked in situ-forming gel. J. Mater. Chem. 2010;20:3265–3271. doi: 10.1039/b922614a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khor E., Wu H., Lim L.Y., Guo C.M. Chitin-methacrylate: Preparation, characterization and hydrogel formation. Materials. 2011;4:1728–1746. doi: 10.3390/ma4101728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim M.S., Hyun H., Khang G., Lee H.B. Preparation of thermosensitived diblock copolymers consisting of MPEG and polyesters. Macromolecules. 2006;39:3099–3102. doi: 10.1021/ma052713d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim M.S., Hyun H., Seo K.S., Cho Y.H., Khang G., Lee H.B. Preparation and characterization of MPEG-PCL diblock copolymers with thermo-responsive sol-gel-sol phase transition. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2006;44:5413–5423. doi: 10.1002/pola.21659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang Y.M., Lee S.H., Lee J.Y., Son J.S., Kim B.S., Lee B., Chun H.J., Min B.H., Kim J.H., Kim M.S. A biodegradable, injectable, gel system based on MPEG-b-(PCL-ran-PLLA) diblock copolymers with an adjustable therapeutic window. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2453–2834. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J.I., Kim D.Y., Kwon D.Y., Kang H.J., Kim J.H., Min B.H., Kim M.S. An injectable biodegradable temperature-responsive gel with an adjustable persistence window. Biomaterials. 2012;33:2823–2834. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyun H., Kim M.S., Jeong S.C., Kim Y.H., Lee S.Y., Khang G., Lee H.B. Preparation of diblock copolymers consisting of methoxy poly(ethyleneglycol) and poly(ε-caprolactone)/poly(L-lactide) and their degradation property. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2006;46:1242–1249. doi: 10.1002/pen.20581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J.I., Lee S.H., Kang H.J., Kwon D.Y., Kim D.Y., Kang W.S., Kim J.H., Kim M.S. Examination of phase transition behavior of ion group functionalized MPEG-b-PCL diblock copolymers. Soft Matter. 2011;7:8650–8656. doi: 10.1039/c1sm05977g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang Y.M., Kim G.H., Kim J.I., Kim D.Y., Lee B.N., Yoon S.M., Kim J.H., Kim M.S. In vivo efficacy of an intratumorally injected in situ-forming doxorubicin/poly(ethylene glycol)-b-polycaprolactoned iblock copolymer. Biomaterials. 2011;32:4556–4564. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee J.Y., Kim K.S., Kang Y.M., Kim E.S., Hwang S.J., Lee H.B., Min B.H., Kim J.H., Kim M.S. In vivo efficacy of paclitaxel-loaded injectable in situ-forming gel against subcutaneous tumor growth. Int. J. Pharm. 2010;392:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyun H., Kim Y.H., Song I.B., Lee J.W., Kim M.S., Khang G., Park K., Lee H.B. In vitro and in vivo release of albumin using a biodegradable MPEG-PCL diblock copolymer as an in situ gel-forming carrier. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:1093–1100. doi: 10.1021/bm060991u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahn H.H., Kim K.S., Lee J.H., Lee J.Y., Lee I.W., Chun H.J., Kim J.H., Lee H.B., Kim M.S. In vivo osteogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells in an injectable in situ-forming gel scaffold. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2009;15:1821–1832. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim M.S., Kim S.K., Kim S.H., Hyun H., Khang G., Lee H.B. In vivo osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow stromal cells in thermosensitive MPEG-PCL diblock copolymer gel. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2863–2873. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park Y.B., Kim Y.Y., Oh S.K., Chung S.G., Ku S.Y., Kim S.H., Choi Y.M., Moon S.Y. Alterations of proliferative and differentiation potentials of human embryonic stem cells during long-term culture. Exp. Mol. Med. 2008;40:98–108. doi: 10.3858/emm.2008.40.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim H., Kim Y.Y., Ku S.Y., Kim S.H., Choi Y.M., Moon S.Y. The effect of estrogen compounds on human embryoid bodies. Reprod. Sci. 2012;20:661–669. doi: 10.1177/1933719112462630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim Y.Y., Ku S.Y., Jang J., Oh S.K., Kim H.S., Kim S.H., Choi Y.M., Moon S.Y. Use of long-term cultured embryoid bodies may enhance cardiomyocyte differentiation by BMP2. Yonsei Med. J. 2008;49:819–827. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2008.49.5.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parsons X.H. An engraftable human embryonic stem cell neuronal lineage-specific derivative retains embryonic chromatin plasticity for scale-up CNS regeneration. J. Regen. Med. Tissue Eng. 2012;1:1–12. doi: 10.7243/2050-1218-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim J., Moon S.H., Lee S.H., Lee D.R., Chung H.M. Isolation and in vivo study of human embryonic stem cells derived endothelial cells to investigate feasibility for vascular tissue regeneration. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2006;3:451–456. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stenberg J., Elovsson M., Strehl R., Kilmare E., Hyllner J., Lindahl A. Sustained embryoid body formation and culture in a non-laborious three dimensional culture system for human embryonic stem cells. Cytotechnology. 2011;63:227–237. doi: 10.1007/s10616-011-9344-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oh S.K., Kim H.S., Kim H.S. Derivation and characterization of new human embryonic stem cell lines: SNUhES1, SNUhES2, and SNUhES3. Stem Cells. 2005;23:211–219. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oh S.K., Kim H.S., Kim H.S. Methods for expansion of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23:605–609. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]