Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine the use of antimuscarinics for treating urinary incontinence (UI) in older adults with varying levels of cognition.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional.

SETTING

National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center from 2005 through 2015.

PARTICIPANTS

Community-dwelling men and women aged 65 and older (N = 24,106).

MEASUREMENTS

Clinicians and staff evaluated each participant’s dementia status during annual in-person assessments. Participants or their informants reported all medications taken in the 2 weeks before each study visit.

RESULTS

Overall, 5.2% (95% confidence interval (CI) = 4.9–5.5%) of the cohort took a bladder antimuscarinic. Participants with impaired cognition were more likely to be taking an antimuscarinic than those with normal cognition. Rates of bladder antimuscarinic use were 4.0% (95% CI = 3.6–4.4%) for participants with normal cognition, 5.6% (95% CI = 4.9–6.3%) for those with mild cognitive impairment, and 6.0% (95% CI = 5.5–6.4%) for those with dementia (p < .001). Of 624 participants with dementia who took antimuscarinics, 16% (95% CI = 13–19%) were simultaneously taking other medicines with anticholinergic properties.

CONCLUSION

Use of bladder antimuscarinics was more common in older adults with impaired cognition than in those with normal cognition. This use is despite guidelines advising clinicians to avoid prescribing antimuscarinics in individuals with dementia because of their vulnerability to anticholinergic-induced adverse cognitive and functional effects. A substantial proportion of cognitively impaired individuals who took antimuscarinics were simultaneously taking other anticholinergic medications. These findings suggest a need to improve the treatment of UI in individuals with impaired cognition.

Keywords: dementia, anticholinergic, urinary incontinence

With the growth of the aging population, the prevalence of dementia in the United States is expected to reach 16 million by 2050, resulting in an estimated $1.2 trillion in costs of care.1 Urinary incontinence (UI) is also a highly prevalent condition that affects 25% to 39% of older adults and is associated with falls and fractures, depression, social isolation, and poor quality of life.2–5 UI is responsible for 6% of nursing home admissions of older women, at a cost of $3 billion per year.6 UI and dementia frequently coexist, but there is great uncertainty about how to manage UI in individuals with dementia.

UI in individuals with dementia is multifactorial. Urge UI, functional disability, and cognitive impairment play important roles.7,8 Nonpharmacological strategies (e.g., pelvic floor muscle training, scheduled voiding) are first-line therapies for urge UI,9 yet there is a dearth of knowledge about how to adapt these methods for people with dementia.10 Second-line therapies include oral anticholinergic medicines (bladder antimuscarinics), including oxybutynin, tolterodine, and trospium, but clinical practice guidelines recommend avoiding antimuscarinics in older adults with dementia because of their vulnerability to anticholinergic-induced adverse cognitive and functional effects.9,11

Anticholinergic side effects include dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, falls, delirium, and cognitive impairment.12,13 As a result of postmarketing surveillance, the Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research approved labeling changes for oxybutynin in 2008 that warn of the risk of aggravating confusion in individuals with dementia treated with cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs).14 Antimuscarinics are believed to directly counteract the already-modest therapeutic effect of ChEIs, which work by increasing acetylcholine in the brain.15 In addition, individuals with dementia treated with antimuscarinics and ChEIs concurrently may have faster rates of functional decline than those treated with ChEIs alone.16 Increasing evidence suggests that cumulative use of anticholinergic medicines, of which antimuscarinics are among the most common, may be associated with incident dementia.17

Little is known about the extent to which clinicians consider an individual’s cognitive status when treating UI. Such information would inform development of interventions to improve the care of older adults with a prevalent and disabling combination of conditions. To understand current prescribing practice, this study used data from individuals with and without cognitive impairment in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) Uniform Data Set (UDS) to examine the use of antimuscarinics in older adults with varying levels of cognition. Secondary objectives were to examine the use of antimuscarinics in persons concurrently receiving other drugs with anticholinergic activity. The use of antimuscarinics in persons concurrently being treated with ChEIs was also examined, because dual use may lead to reduced effectiveness of both drugs.

METHODS

Study Population

This was a cross-sectional study using the UDS collected from September 2005 through March 2015. Recruitment and assessment of participants have been described elsewhere.18 The UDS contains demographic and clinical data from participants with normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and dementia who are assessed longitudinally at one of 34 Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADCs) funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA).18 Written informed consent is obtained from each participant or legally authorized representative, and the institutional review board overseeing each ADC approves procedures. Each participant, including those with normal cognition, has a collateral source, usually a relative or close friend, who serves as their study partner during the ADC assessment.

Community-dwelling individuals aged 65 and older (living in an independent family residence or retirement community) at baseline were included. Assessments are obtained annually.

Measurement of Cognitive Status

Research-trained clinicians from each center follow a uniform protocol to collect data from the participant and the participant’s informant during annual in-person assessments. The neuropsychological test battery is designed to measure attention, processing speed, executive function, episodic memory, and language.19 The battery includes the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised (WMS-R) Logical Memory, Digit Span Backward, Digit Span Forward, and Logical Memory Delayed; Category Fluency; Trail-Making Test Parts A and B; Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised Digit Symbol; Boston Naming Test; and Mini-Mental State Examination.

NACC participants receive a diagnosis adjudicated by an experienced clinician or interdisciplinary team. Diagnosis is made clinically, based on the individual’s history and performance on the neuropsychological test battery, not on the basis of strict cutoffs on neuropsychological tests. Cognition is classified as normal if the participant lacks clinically significant cognitive or functional impairment; “impaired, not MCI” if the participant is cognitively impaired but the tests, symptoms, and clinical evaluation are not consistent with MCI; MCI if they have objective or subjective evidence of cognitive impairment but no clinically significant functional impairment; and dementia if they have clinically significant cognitive and functional impairment.

Antimuscarinic Use

A standardized form is used to collect medication data, which are linked to drug identification codes. Research-trained clinicians ask the participant and informant to name all prescription and nonprescription drugs, vitamins, and supplements that the participant has taken within the 2 weeks before each assessment.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed at the time of the last visit for each participant. To determine the demographic characteristics of the study population, univariate analysis was performed using analysis of variance for continuous data and chi-square analysis for categorical data.

Standard descriptive methods were used to estimate the proportion of participants, stratified according to cognitive status, who reported using any of the following antimuscarinics at their last visit: oxybutynin, tolterodine, fesoterodine, solifenacin, darifenacin, trospium, and flavoxate. Confidence intervals (CIs) around the proportion were estimated using the Wald method, and proportions were compared using the chi-square test.

Next, the proportion of participants who reported using antimuscarinics while simultaneously taking other medicines with Anticholinergic Drug Scale (ADS) scores of 2 or 3 was calculated. The ADS is an expert-derived drug rating scale to quantify anticholinergic burden;20 drugs are rated on an ordinal scale from 0 to 3, receiving a score of 2 if anticholinergic adverse events are sometimes noted, usually at excessive doses, and a score of 3 if they are deemed markedly anticholinergic.

The use of antimuscarinics in participants concurrently receiving ChEIs and the use of ChEIs before inception of antimuscarinic treatment were also examined. The following ChEIs were included: tacrine, galantamine, donepezil, and rivastigmine.

To determine whether the results were similar when the prevalence of antimuscarinic use was calculated according to cognitive status each calendar year instead of at the last visit, year-specific analyses were performed for the years in which there were sufficient data (2006–2014). The annual prevalence of antimuscarinic use was calculated for participants in each cognitive group, and the CIs around the proportion were estimated using the Wald method. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

During the 10-year study period, there were 24,106 community-dwelling participants aged 65 and older at their first visit.

Characteristics at the last visit are shown in Table 1. Participants with dementia were older and had less education. They had greater comorbidity, functional impairment, and depressive symptomatology and were taking more medicines. In total, 8,239 (34.1%) had normal cognition, 995 (4.1%) were classified as “impaired, not MCI,” 4,381 (18.2%) had MCI, and 10,491 (43.5%) had dementia.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Population According to Cognitive Status at Last Visit

| Characteristic | Normal Cognition, N = 8,239 |

Impaired, Not MCI, N = 995 |

MCI, N = 4,381 |

Dementia, N = 10,491 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 74.7 ± 6.9 | 74.9 ± 6.8 | 76.7 ± 7.0 | 77.2 ± 6.9 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 5,265 (63.9) | 569 (57.2) | 2,271 (51.8) | 5,459 (52.0) |

| Female | 2,974 (36.1) | 426 (42.8) | 2,110 (48.2) | 5,032 (48.0) |

| Education, years, mean ± SD | 15.5 ± 3.2 | 14.7 ± 3.9 | 14.9 ± 3.6 | 14.2 ± 3.9 |

| Mini-Mental State Examination score, mean ± SD (range 0–30)a | 28.7 ± 1.6 | 27.6 ± 2.6 | 26.7 ± 2.7 | 18.4 ± 7.0 |

| Geriatric Depression Scale score, mean ± SD (range 0–15)b | 1.4 ± 2.0 | 2.7 ± 2.9 | 2.6 ± 2.7 | 2.7 ± 2.8 |

| Functional Status, mean ± SD (range 0–30)c | 0.5 ± 2.0 | 2.9 ± 5.0 | 3.9 ± 5.1 | 19.2 ± 8.8 |

| Number of comorbidities, mean ± SDd | 2.1 ± 1.5 | 2.4 ± 1.6 | 2.3 ± 1.6 | 2.4 ± 1.6 |

| Total number of medicines, mean ± SD | 6.8 ± 4.2 | 7.1 ± 4.2 | 6.8 ± 4.2 | 6.7 ± 3.9 |

Lower scores indicate worse cognitive function.

Higher scores indicate greater depressive symptomatology.

Scores of 9 and greater (dependent in 3 or more activities) indicate impaired function.

Heart attack, cardiac arrest, congestive heart failure, other cardiovascular disease, stroke, transient ischemic attack, other cerebrovascular disease, Parkinson’s disease, other Parkinsonism disorder, seizures, other neurological conditions, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, urinary or bowel incontinence, depression, other psychiatric disorders, alcohol abuse, cigarette smoking, abuse of other substances.

MCI = mild cognitive impairment; SD = standard deviation.

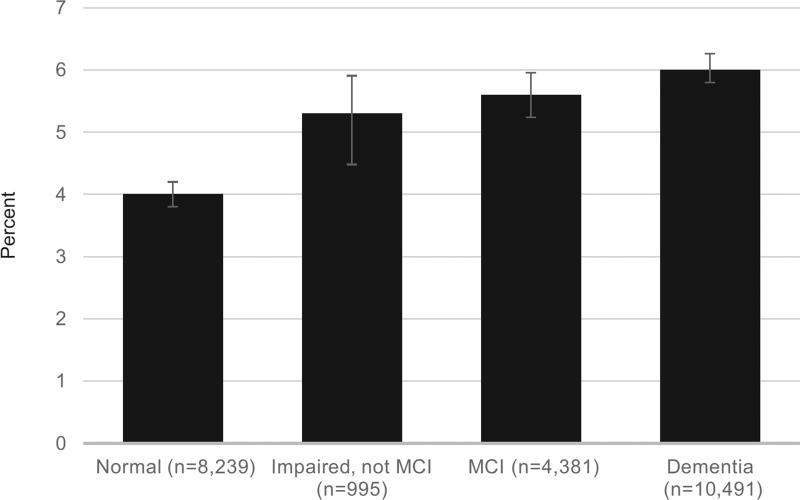

Overall, 5.2% (95% CI = 4.9–5.5%) of the cohort was taking an antimuscarinic. Oxybutynin and tolterodine were the most commonly used antimuscarinics; fesoterodine and flavoxate were least common. Participants with impaired cognition were more likely to be taking an antimuscarinic than those with normal cognition. Rates of antimuscarinic use were 4.0% (95% CI = 3.6–4.4%) for participants with normal cognition, 5.2% (95% CI = 4.1–6.9%) for participants classified as “impaired, not MCI,” 5.6% (95% CI = 4.9–6.3%) for participants with MCI, and 6.0% (95% CI = 5.5–6.4%) for participants with dementia (P < .001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Use of bladder antimuscarinics according to cognitive status, assessed at the last visit.

Of 243 participants with MCI who took antimuscarinics, 16% (95% CI = 12–21%) were simultaneously taking other medicines with ADS scores of 2 or 3. Of 624 participants with dementia who took antimuscarinics, 16% (95% CI = 13–19%) were simultaneously taking other medicines with ADS scores of 2 or 3.

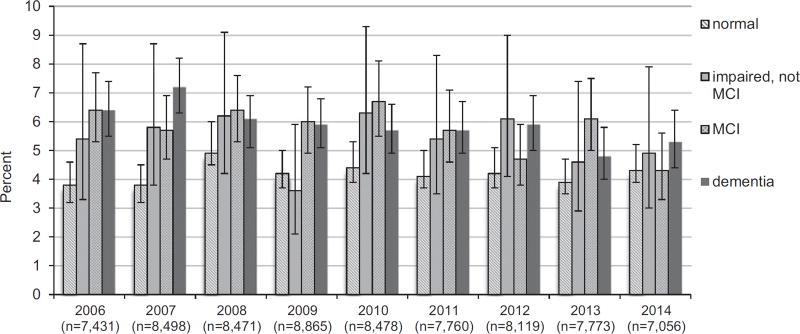

Of 1,249 participants taking antimuscarinics, 506 (41%, 95% CI = 38–43%) were concurrently taking a cholinesterase inhibitor. At the time of bladder antimuscarinic initiation, 331 participants (27%, 95% CI = 24–29%) were taking a cholinesterase inhibitor. The proportion of participants taking antimuscarinics was consistent in each of the 10 years (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Annual prevalence of bladder antimuscarinic use according to cognitive status.

DISCUSSION

The major finding was that participants with MCI and dementia were more likely to receive antimuscarinics than those with normal cognition. A considerable number of participants with impaired cognition simultaneously took antimuscarinics and other medicines with anticholinergic activity. The increasing prevalence of UI with increasing severity of dementia may explain this use,21 but these prescribing patterns are troubling in light of practice guidelines and consensus statements from the American Urological Association and American Geriatrics Society that urge caution in prescribing anticholinergic medicines such as antimuscarinics in individuals with cognitive deficits.9,11

Antimuscarinic use was common in individuals receiving ChEIs for treatment of dementia. This is consistent with a previous study that examined pharmacy claims for Iowa’s Medicaid population and found that 35% of those receiving ChEIs were receiving at least one other anticholinergic medicine, with the antimuscarinics oxybutynin and tolterodine among the most common.15 Concomitant use of antimuscarinics and ChEIs is also common in nursing homes, despite the fact that these are regulated settings where the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services require that each resident have a monthly prescription review by a pharmacist. A recent study of U.S. nursing homes found that 24% of residents with overactive bladder (OAB) or UI were prescribed an antimuscarinic concomitantly with a ChEI.16,22 Dual use of ChEIs and antimuscarinics may not only render both medicines ineffective, but may also be harmful. Previous research has shown that higher-functioning nursing home residents receiving ChEIs together with antimuscarinics have faster functional decline than similar residents receiving ChEIs alone.16 Many participants were taking a ChEI before inception of the antimuscarinic. This may be evidence of the prescribing cascade, in which a second drug is prescribed to treat the side effects of another drug. ChEIs can exacerbate urge UI through their actions on the autonomic nervous system, leading to greater risk of receiving an anticholinergic drug to manage UI.23

The reasons for the prescribing patterns found are unclear. The perspectives of individuals with dementia and their caregivers for UI treatment have been largely absent from previous research. Like many day-to-day medical decisions for older adults, treatment of urge UI in the context of dementia requires consideration of trade-offs. Because UI can be so distressing, some individuals and their caregivers may choose to use an antimuscarinic despite the risk of adverse cognitive effects, but exposure to even low doses could be harmful in older adults with dementia, who may be on the cusp of losing independence. Furthermore, because UI in dementia is usually multifactorial and due in large part to cognitive and functional impairments, the benefits of antimuscarinics may be attenuated.8 Data on the effectiveness of antimuscarinics in individuals with cognitive impairment are limited.24 A study of hospitalized older adults found that equal proportions would choose to manage their incontinence with diapers as would choose medication.25 Medicare does not cover continence products, such as diapers and pads, a factor that may affect individual and caregiver decision-making. The role of comorbidities and geriatric conditions that may alter an individual’s ability to achieve treatment benefit from behavioral therapies is unknown. For example, mobility impairment, chronic pain, or dyspnea may make scheduled toileting difficult, or treatments for heart failure may exacerbate UI.

There are limitations to this analysis, the major one being reliance on self-reported medication use. The NACC UDS does not capture information on dose, frequency, or duration of medication use. There was not a specific search for patch and gel forms of oxybutynin or for older antimuscarinics. Another limitation is that NACC data is collected at the NIA’s ADCs, which are primarily at urban academic medical centers. Thus, the generalizability of the findings to the U.S. population is unknown. Finally, the NACC UDS does not include data on the prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms, UI, or OAB. For this reason, to what extent, if any, clinicians consider cognitive status when prescribing antimuscarinics could not be directly assessed. It was also not possible to determine what symptoms antimuscarinics were being prescribed to treat.

UI and dementia are quintessential geriatric syndromes—multifactorial conditions that arise as a result of accumulated deficits in multiple organ systems. As such, they are particularly challenging to treat. Care for geriatric conditions, including UI and dementia, is of poorer quality than care provided for general medical conditions, as evidenced by adherence to quality indicators for vulnerable older adults. For example, previous research has documented that, when older adults with poor functional status present with new or worsening UI, fewer than one-quarter of physicians take an incontinence history or perform a relevant physical examination.26 Interventions for geriatric conditions such as UI require “a more cohesive and coordinated approach,”27 and “human capital, rather than simply a new drug or technology.”28

Nonpharmacological approaches to treat UI in older adults with dementia are underused. Although two-thirds of people with dementia live at home, a 2012 systematic review identified only three studies, all more than a decade old, of nonpharmacological and nonsurgical interventions to treat UI in community-dwelling individuals with dementia. Two studies were exploratory or pilot studies.10 All involved substantial effort on the part of the caregiver.

Clinicians should engage individuals and caregivers in shared decision-making regarding treatment of UI in the context of cognitive impairment. Discussions about antimuscarinics should include what is known about the risks and benefits. If an individual or caregiver opts for a trial of pharmacological therapy, mirabegron (a novel beta-3 agonist) may be a safer alternative to antimuscarinics, although data are sparse in cognitively impaired older adults.29 Other pharmacological choices merit further study. Future research should test nonpharmacological interventions to improve the care of older adults with UI and dementia, such as a multicomponent intervention involving an individualized continence plan, caregiver education, and ongoing monitoring and support.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Johns Hopkins Clinical Research Scholars Program (KL2) (ARG); 1K23AG043504–01, the Roberts Fund (EO); the MSTAR program (LH); and the Paul Beeson Career Development Award Program: NIA 1K23AG032910, American Federation for Aging Research, The John A. Hartford Foundation, the Atlantic Philanthropies, the Starr Foundation, and an anonymous donor (CMB).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None.

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: ARG, EO, CMB. Analysis and interpretation of data: ARG, JT, EO, DLR, LH, CMB. Preparation of manuscript: ARG. Editing of manuscript: ARG, JBS, JT, EO, DLR, LH, JLD, CMB

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsors had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection or analysis, or preparation of the paper.

References

- 1.Campbell NL, Boustani MA. Adverse cognitive effects of medications: Turning attention to reversibility. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:408–409. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo X, Chuang CC, Yang E, et al. Prevalence, management and outcomes of medically complex vulnerable elderly patients with urinary incontinence in the United States. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69:1517–1524. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sexton CC, Coyne KS, Thompson C, et al. Prevalence and effect on health-related quality of life of overactive bladder in older Americans: Results from the Epidemiology of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1465–1470. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown JS, Vittinghoff E, Wyman JF, et al. Urinary incontinence: Does it increase risk for falls and fractures? Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:721–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gnanadesigan N, Saliba D, Roth CP, et al. The quality of care provided to vulnerable older community-based patients with urinary incontinence. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5:141–146. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000123026.47700.1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrison A, Levy R. Fraction of nursing home admissions attributable to urinary incontinence. Value Health. 2006;9:272–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lifford KL, Townsend MK, Curhan GC, et al. The epidemiology of urinary incontinence in older women: Incidence, progression, and remission. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1191–1198. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yap P, Tan D. Urinary incontinence in dementia—a practical approach. Aust Fam Physician. 2006;35:237–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2012;188(6 Suppl):2455–2463. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drennan VM, Greenwood N, Cole L, et al. Conservative interventions for incontinence in people with dementia or cognitive impairment, living at home: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Geriatrics Society. updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;2015:2227–2246. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moga DC, Carnahan RM, Lund BC, et al. Risks and benefits of bladder antimuscarinics among elderly residents of Veterans Affairs community living centers. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:749–760. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kay GG, Abou-Donia MB, Messer WS, Jr, et al. Antimuscarinic drugs for overactive bladder and their potential effects on cognitive function in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:2195–2201. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safety Labeling Changes Approved By FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research [on-line] [Accessed May 27, 2016]; Available at http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/Safety-RelatedDrugLabelingChanges/ucm113884.htm.

- 15.Carnahan RM, Lund BC, Perry PJ, et al. The concurrent use of anticholinergics and cholinesterase inhibitors: Rare event or common practice? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:2082–2087. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sink KM, Thomas J, III, Xu H, et al. Dual use of bladder anticholinergics and cholinesterase inhibitors: Long-term functional and cognitive outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:847–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray SL, Anderson ML, Dublin S, et al. Cumulative use of strong anticholinergics and incident dementia: A prospective cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:401–407. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): Clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:210–216. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213865.09806.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weintraub S, Salmon D, Mercaldo N, et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Centers’ Uniform Data Set (UDS): The neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:91–101. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318191c7dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carnahan RM, Lund BC, Perry PJ, et al. The Anticholinergic Drug Scale as a measure of drug-related anticholinergic burden: Associations with serum anticholinergic activity. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46:1481–1486. doi: 10.1177/0091270006292126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hellstrom L, Ekelund P, Milsom I, et al. The influence of dementia on the prevalence of urinary and faecal incontinence in 85-year-old men and women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1994;19:11–20. doi: 10.1016/0167-4943(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zarowitz BJ, Allen C, O’Shea T, et al. Challenges in the pharmacological management of nursing home residents with overactive bladder or urinary incontinence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2298–2307. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gill SS, Mamdani M, Naglie G, et al. A prescribing cascade involving cholinesterase inhibitors and anticholinergic drugs. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:808–813. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.7.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ouslander JG, Schnelle JF, Uman G, et al. Does oxybutynin add to the effectiveness of prompted voiding for urinary incontinence among nursing home residents? A placebo-controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:610–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfisterer MH, Johnson TM, II, Jenetzky E, et al. Geriatric patients’ preferences for treatment of urinary incontinence: A study of hospitalized, cognitively competent adults aged 80 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:2016–2022. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wenger NS, Solomon DH, Roth CP, et al. The quality of medical care provided to vulnerable community-dwelling older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:740–747. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-9-200311040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tinetti ME, Inouye SK, Gill TM, et al. Shared risk factors for falls, incontinence, and functional dependence. Unifying the approach to geriatric syndromes. JAMA. 1995;273:1348–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, et al. Geriatric syndromes: Clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turpen HC, Zimmern PE. Mirabegron: A new option in treating overactive bladder. JAAPA. 2015;28(16):18. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000472558.50124.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]