Abstract

Diabetes during pregnancy is associated with abnormal placenta mitochondrial function and increased oxidative stress, which affect fetal development and offspring long-term health. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) is a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and energy metabolism. The molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of PGC-1α in placenta in the context of diabetes remain unclear. The present study examined the role of microRNA 130b (miR-130b-3p) in regulating PGC-1α expression and oxidative stress in a placental trophoblastic cell line (BeWo). Prolonged exposure of BeWo cells to high glucose mimicking hyperglycemia resulted in decreased protein abundance of PGC-1α and its downstream factor, mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM). High glucose treatment increased the expression of miR-130b-3p in BeWo cells, as well as exosomal secretion of miR-130b-3p. Transfection of BeWo cells with miR-130b-3p mimic reduced the abundance of PGC-1α, whereas inhibition of miR-130b-3p increased PGC-1α expression in response to high glucose, suggesting a role for miR-130b-3p in mediating high glucose-induced down regulation of PGC-1α expression. In addition, miR-130b-3p anti-sense inhibitor increased TFAM expression and reduced 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE)-induced production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Taken together, these findings reveal that miR-130b-3p down-regulates PGC-1α expression in placental trophoblasts, and inhibition of miR-130b-3p appears to improve mitochondrial biogenesis signaling and protect placental trophoblast cells from oxidative stress.

Keywords: Hyperglycemia, placental trophoblast, PGC-1α, miR-130b, oxidative stress

Introduction

The placenta is a highly active metabolic and endocrine organ playing special roles in supporting fetal growth and development [1–3]. During pregnancy, active nutrient transport across placenta and synthesis of placental hormones require sufficient supply of ATP, which is mainly derived from mitochondria [4–6]. The adverse diabetic environment, with hyperglycemia, inflammation, and dyslipidemia, impairs mitochondrial function in placental cells, potentially leading to aberrant oxidative phosphorylation and increased oxidative stress, which can influence fetal development and offspring long-term health [3, 7, 8].

Previous studies by our group and others have demonstrated that diabetes during pregnancy is associated with a decrease in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) protein in human placentae [9, 10]. PGC-1α is a transcription coactivator that interacts with multiple transcription factors involved in energy metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis [11, 12]. PGC-1α is expressed at high levels in tissues with an abundance of mitochondria and active oxidative metabolism and responds to increased energy needs [11, 13–15]. In muscle, for example, PGC-1α activates mitochondrial biogenesis, increases fatty acid oxidation and glucose transporter GLUT4 expression, which in turn reduce fat accumulation and increase insulin sensitivity [16]. Given the role as a regulator of mitochondrial function and expression of anti-oxidant enzymes [12, 17, 18], PGC-1α could have an important role in maintaining normal placental function. However, the determinants of placental PGC-1α in response to diabetic conditions are poorly understood.

The present study assessed the regulation of PGC-1α expression by microRNAs. These small non-coding RNAs negatively regulate abundance of proteins involved in various physiological and pathological cellular processes by affecting translation or stability of targeted mRNAs [19]. Previous studies in our laboratory demonstrated increased expression of several microRNAs, including microRNA-130b (miR-130b-3p) and microRNA-148a (miR-148a-3p), in human umbilical vein endothelial cells from offspring of diabetic mothers [20]. These 2 miRNAs in particular has been predicted to target PGC-1α. Therefore, we examined how diabetes-related factors regulate the expression of these miRNAs in trophoblastic BeWo cells, and studied the potential involvement of miR-130b-3p in mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative stress responses.

Research Design and Methods

Cell culture

BeWo cells (a male human placental trophoblast cell line originating from choriocarcinoma, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were cultured in Ham's F-12 medium (Gibco/Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% FBS (Mediatech, Manassas, VA), 100 µM MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids (Gibco/Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), and 0.5% penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin B (Gibco/Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) at 37°C, 5% CO2. To mimic diabetes-associated conditions, BeWo cells were exposed to medium containing 42 mM of D-glucose or osmotic control mannitol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), oxidative stress inducer 4-hydroxynonenal (Cayman, Ann Arbor, Michigan), sodium palmitate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), or the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα (R&D, Minneapolis, MN) for the indicated time and doses as described in figure legends.

Transfection of miRNA mimic or inhibitor

The BeWo cells were transfected with the mirVana™ miRNA mimics of miR-130b-3p (100 nM), miR-130b-3p anti-sense inhibitor (100 nM) or the same amounts of mirVana™ miRNA Negative Control (a synthetic miRNA sequence with no known homology to the human transcriptome) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Transfection reagent (0.25 µl RNAiMAX/100 µl medium, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Efficiency of transfection was verified by real-time PCR (data not shown).

Western Blot Analysis

BeWo cells were lysed and homogenized in protein lysis buffer containing a protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Protein concentrations were measured by BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Protein lysate (30 µ g) was treated with Laemmli sample buffer containing Dithiothreitol (DTT), subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane followed by incubation with antibodies specific for PGC-1α (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), TFAM or β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) at 1:1000 dilution. Detected bands at expected size were analyzed by imaging densitometry with Image Lab Software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

RNA extraction

Isolation of RNA was accomplished using the miRNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of isolated total RNA and presence of miRNA were determined using the small RNA chip on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

qPCR analysis

Reverse transcription was done using the TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and a pool of miRNA-specific RT primers according to the Applied Biosystems protocol (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). All qPCR reactions for miRNAs were performed using TaqMan Universal Master Mix II, no UNG (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) as previously described [20]. Relative expression of individual miRNA species was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method [21] with the software DataAssist, where RNU48 served as the endogenous control miRNA.

Exosomal isolation

Exosomes were isolated from conditioned medium of BeWo cells with ExoQuick-TC Exosome Precipitation Solution according to manufacturer’s manual (System Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA). RNA and proteins were extracted from precipitated exosomes and subjected to qPCR and Western blot analysis.

DHR-123 staining

Production of ROS was detected with a cell-permeable fluorogenic probe, dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR-123, Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The cells were loaded with DHR-123 (12 µM) for 20 minutes at 37 °C followed by detecting the intracellular rhodamine with a fluorescent microscope (ZOE Fluorescent Cell Imager, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Fluorescent intensity was quantified with ImageJ software.

Statistical methods

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Differences between two groups were assessed using Student’s t-test. Software Excel was used for Data analyses and bar graph plotting. P-values <0.05 were treated as statistically significant.

Results

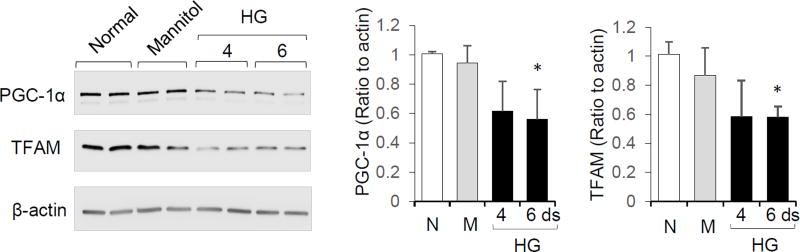

High glucose media decreases PGC-1α and TFAM expression

PGC-1α stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis by activating transcription factors that promote expression of TFAM, which directly regulates mitochondrial DNA transcription and replication [22]. To examine the regulation of PGC-1α and TFAM expression in placental cells under diabetic conditions, cultured BeWo cells were exposed to high glucose medium (42 mM) for 4 and 6 days and compared to an osmotic control containing mannitol. PGC-1α and TFAM protein abundance were significantly decreased by 44% and 42% respectively following treatment with high glucose for 6 days (Figure 1). In contrast, there was no significant effect of mannitol on PGC-1α or TFAM expression compared to normal growth medium (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Regulation of PGC-1α/TFAM in BeWo cells by glucose. BeWo cells were cultured in normal medium (N, 10mM glucose, for 6 days), medium with high glucose (HG, 42mM, for 4 or 6 days), or osmotic control mannitol (M, 10mM glucose+32 mM mannitol, for 6 days). For HG 4-days treatment group, cells were incubated in osmotic control medium for 2 days followed by high glucose treatment for 4 days. Representative Western blots, and bar graphs of PGC-1α and TFAM quantification are shown. Mean ± SD, n=3, * P<0.05 compared to mannitol group.

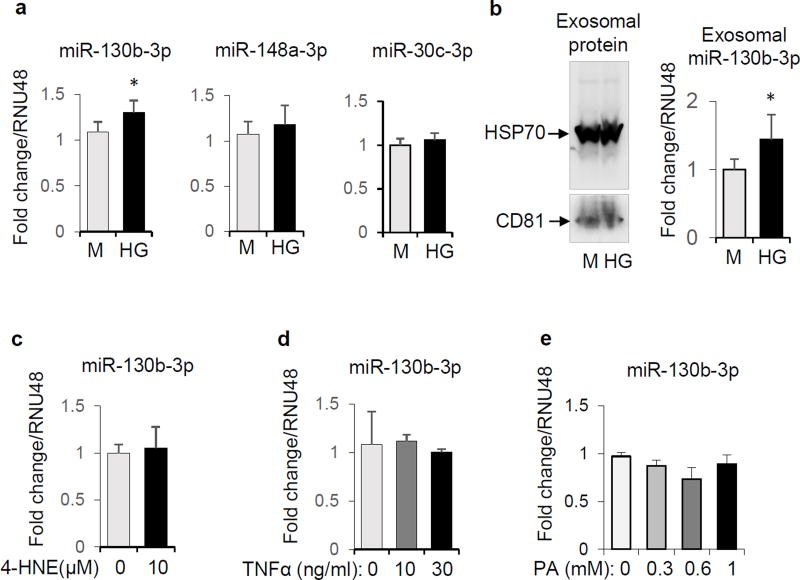

High glucose media increases expression of miR-130b-3p

Exposure of BeWo cells to 42 mM glucose for 24 h increased the expression of miR-130b-3p, but not miR-148a-3p nor miR-30c-5p, which also are predicted to target PGC-1α mRNA (microRNA.org; Figure 2a). Furthermore, high glucose treatment increased the abundance of exosomal miR-130b-3p in cultured media of BeWo cells (Figure 2b) after 72 h. In contrast, expression of miR-130b-3p in BeWo cells was not increased in response to other diabetes-related insults, including the oxidative stress inducer 4-HNE, the inflammatory factor TNFα, or the saturated fatty acid palmitate (Figure 2c, d and e).

Figure 2.

Regulation of miR-130b-3p expression in BeWo cells. a: BeWo cells were cultured in medium with high glucose (42mM) or mannitol (M) for 24 hours. The miRNA abundance from cell extracts was quantified by qPCR, n=4. b: BeWo cells were cultured in high glucose (42mM) or mannitol (M) for 72 hours, after which exosomes were isolated from medium (verified by Western blot analysis with exosome-specific antibodies for HSP70 and CD81, left panel). Exosome-associated miR-130b-3p quantified by qPCR (right panel, n=5). c, d and e: BeWo cells were treated with 4-HNE (10 µM) (c, n=4), TNFα (0, 10, 30 ng/ml) (d, n=2–3) or palmitate (0, 0.3, 0.6, and 1 mM) (e, n=2) for 16 hours, and miR-130b-3p levels in cells were quantified by qPCR. * P<0.05.

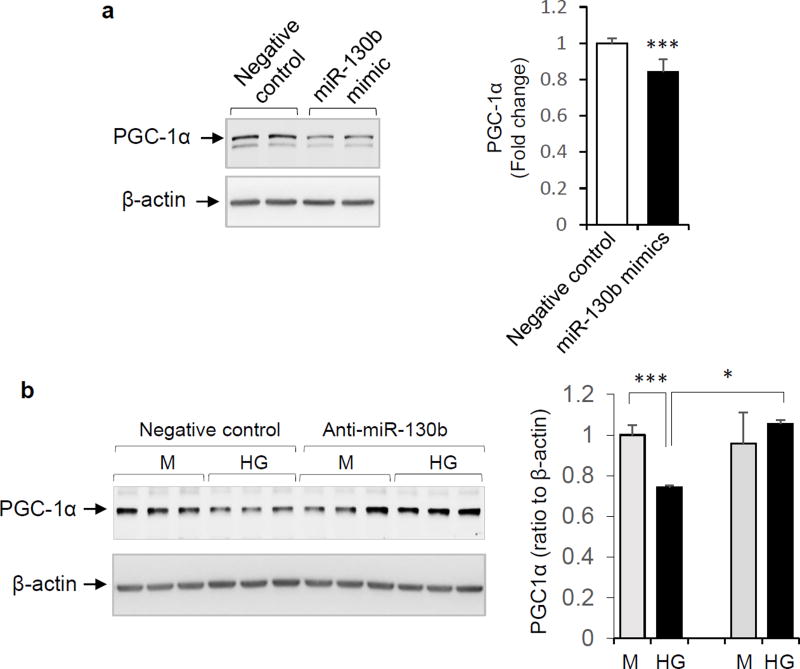

miR-130b-3p mediates high glucose-induced decrease in PGC-1α expression in BeWo cells

The role of miR-130b-3p in regulating PGC-1α expression in placental cells was next assessed. Transfection of BeWo cells with a miR-130b-3p mimic decreased expression of PGC-1α (Figure 3a). Alternatively, when BeWo cells were transfected with the miR-130b-3p anti-sense inhibitor (anti-miR-130b-3p), the expected reduction of PGC-1α in response to high glucose (42mM) was abrogated (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Regulation of PGC-1α expression by miR-130b-3p. a: BeWo cells were transfected with 100 nM of miR-130b-3p mimic or negative control. PGC-1α protein expression was determined after 2 days. Left panel: representative Western blot. Right panel: Quantification of expression (mean ± SD, n=6, *** P < 0.001). b: BeWo cells were transfected with anti-sense miR-130b-3p (anti-miR-130b, 100 nM) or negative control (100 nM), then incubated in medium containing high glucose (42 mM) or mannitol for 3 days. Representative Western blots (left panel) and quantification of PGC-1α protein abundance (right panel) are shown. Mean ± SD, n=3 – 4, * P < 0.05.

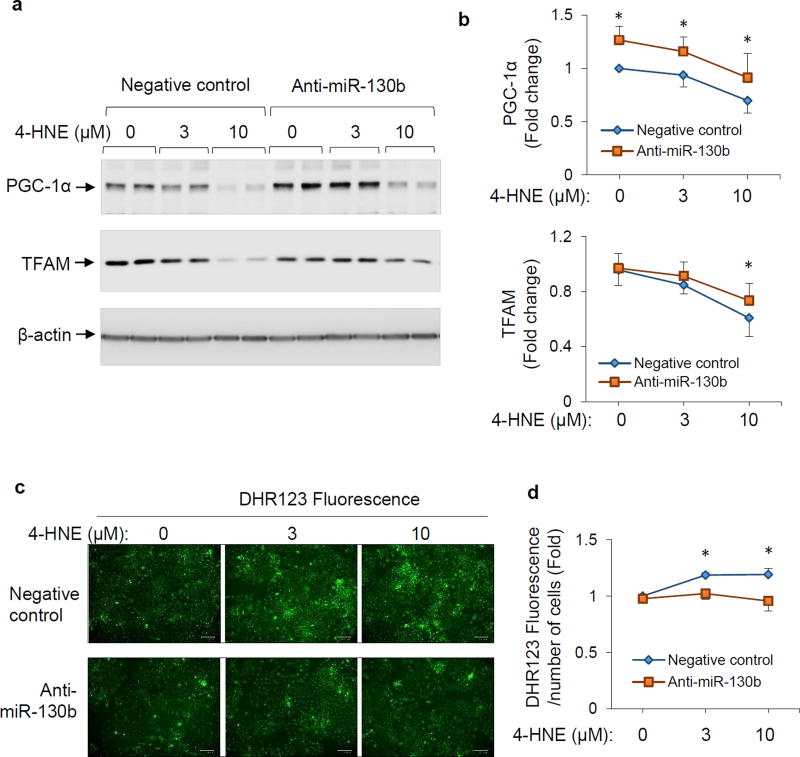

Inhibition of miR-130b-3p increased TFAM expression and reduced 4-HNE-induced production of reactive oxygen species

To examine the role of miR-130b-3p in the response to oxidative stress we exposed BeWo cells to the oxidative stress inducer 4-HNE. This resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in abundance of PGC-1α and TFAM (Figure 4a and 4b). Inhibition of miR-130b-3p with anti-miR-130b-3p increased PGC-1α abundance in the basal state as well as upon 4-HNE treatment (Figure 4a and 4b). As expected, 4-HNE-induced decrease in TFAM expression was partially attenuated by anti-miR-130b-3p (Figure 4a and 4b). Production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in BeWo cells was measured by staining the cells with DHR123 fluorescent probes. As the results show in Figure 4c and 4d, increased ROS production upon 4-HNE exposure was inhibited by anti-miR-130b-3p. These findings suggest a role for miR-130b-3p inhibitor in improving mitochondrial biogenesis and protecting cells from oxidative stress, likely due to upregulation of PGC-1α expression and consequent increase in TFAM.

Figure 4.

Effects of miR-130b-3p inhibition on TFAM expression and ROS production in response to 4-HNE in BeWo cells. BeWo cells were transfected with miR-130b mimic or negative control (100 nM), maintained in culture for 48 h, and then exposed to 4-HNE (0, 3, or 10 µM) for 6 hours in serum free medium. a and b: Cell protein extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis. Representative blots (a) and quantification (b) of PGC-1α and TFAM protein levels were shown. Mean ± SD, n=4–5, * P < 0.05 compared to negative control at each dose of 4-HNE treatment. c and d: Production of ROS was determined with probe DHR-123. Representative images (c) and intensity of green fluorescence (d) were shown. Mean ± SD, n=3–5, * P < 0.05 compared to negative control at each dose of 4-HNE treatment.

Discussion

The present study identifies a potential mechanism for the decreased PGC-1α expression and mitochondrial biogenesis in placentae of offspring born to women with diabetes during pregnancy [10]. Using the human trophoblastic BeWo cell line as a model, we found that exposure to high glucose increased expression of miR-130b-3p, concomitant with reduced PGC-1α and TFAM expression. Moreover, transfection with miR-130b-3p mimic reduced PGC-1α expression, whereas inhibition of miR-130b abrogated the reduction of PGC-1α protein in response to high glucose. Thus we postulate that in a pregnancy complicated by diabetes, hyperglycemia increases placental expression of miR-130b-3p which diminishes the abundance of PGC-1α and thereby influences mitochondrial biogenesis via a reduction in TFAM.

An increase in oxidative stress induced by 4-HNE also reduced abundance of PGC-1α and TFAM, although in the absence of any change in miR-130b-3p expression. However, the effects of miR-130b-3p were evident as an inhibitor of miR-130b-3p both increased protein abundance of PGC-1α and TFAM, and reduced production of ROS induced by 4-HNE. These data provide additional evidence that miR-130b-3p has the capacity to influence mitochondrial biogenesis and the response to oxidative stress by affecting PGC-1α abundance.

A role for PGC-1α involvement in metabolic disorders and links with miR-130b-3p is supported by previous reports. PGC-1α expression is decreased in skeletal muscle of patients with type 2 diabetes [23]. PGC-1α expression is suppressed by hyperglycemia has also been reported in isolated rat islets[24] and vascular smooth muscle cells [25]. miR-130b-3p directly down-regulates PGC-1α expression in adipocytes and hepatocytes [26, 27].

Placentae are exposed to substantial oxidative stress due to high energy demand and increased mitochondrial metabolic activity during pregnancy [28]. Pathological pregnancies, including maternal diabetes, are associated with increased oxidative stress due to overproduction of reactive oxygen species and/or a defect in the antioxidant defenses [29]. Given the high metabolic rate and energy demand in placenta, the decreased PGC-1α/TFAM mitochondrial biogenesis signaling in trophoblasts in response to high glucose can lead to decreased placental oxidative metabolism and anti-oxidant capacity, which contribute to adverse pregnant outcomes of diabetes. Inhibition of miR-130b-3p, via an increase in PGC-1α and TFAM, has a protective role in placental function by improving mitochondrial biogenesis and suppressing oxidative stress, and therefore miR-130b-3p represents a potential therapeutic target for pathological conditions such as maternal diabetes.

Prior studies implicate miR-130b-3p in the pathogenesis of obesity and type 2 diabetes. It is increased in the circulation of adults with type 2 diabetes and obese children [30, 31], and have the potential to exert effects in multiple tissues. Our observation that high glucose exposure increased exosomal secretion of miR-130b-3p from BeWo cells suggests a mechanism by which miR-130b-3p could affect neighboring or distant cells in addition to the cells of origin.

The limitation of the present study is that the experiments used only an established placental cell line. Nevertheless, this work links characteristic metabolic aberrances of diabetes with changes in miR-130b-3p that resultant in important downstream effects on determinants of mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Further studies examining expression of miR-130b-3p and the PGC-1α/TFAM pathway in intact placentae and or primary cultured trophoblasts are warranted. In addition to PGC-1α, miR-130b-3p is known to target other proteins involved in energy metabolism, such as AMP-activated protein kinase α1 (AMPKα1) [20, 27]. We recently reported that placental AMPKα1 is also reduced in diabetic women [20]. Thus miR-130b-3p could be acting indirectly or additively through AMPK, since activated AMPK can upregulate PGC-1α expression [32].

In summary, we found that an increase in miR-130b-3p mediates high glucose-induced reduction in PGC-1α protein in trophoblastic cells. miR-130b-3p was not induced by 4-HNE in BeWo cells, nor by the pro-inflammatory factor TNFα or the free fatty acid palmitate, suggesting that glucose exposure is that main factor driving the increase in miR-130b-3p. As PGC-1α expression is decreased as in skeletal muscle of adults born to mothers with gestational diabetes [33], reduction in PGC-1α expression could explain some of the metabolic features not only of T2DM but also the increased risk of diabetes in children born to women with diabetes during pregnancy.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

High glucose reduces PGC-1α and TFAM proteins in trophoblast BeWo cells

miR-130b-3p mediates high glucose-induced decrease in PGC-1α abundance

Inhibition of miR-130b-3p improves mitochondrial biogenesis signaling

Inhibition of miR-130b-3p protects trophoblasts against oxidative stress

Acknowledgments

We thank the Laboratory for Molecular Biology and Cytometry Research at OUHSC for the use of the Core Facility which provided miRNA analysis using the small RNA chip on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. We thank Drs. Kevin Short and David P Sparling for help and comments.

Funding:

This study was supported by NIH Grants R01 DK089034 (S. Chernausek, PI) and P20 MD000528 (T. Lyons, Project PI); the CMRI Metabolic Research Program; and Harold Hamm Diabetes Center training grant (S. Jiang).

Abbreviations

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- DHR123

Dihydrorhodamine 123

- 4-HNE

4-hydroxynonenal

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

- PGC-1α

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TFAM

Mitochondria transcription factor A

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Duality of interest:

There is no conflict of interest associated with this manuscript.

Author contributions:

All authors contribute to the conception, design and interpretation of the data. SJ, AMT, and JBT performed the experiments. SJ and SDC wrote the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript and approved this version to be published.

References

- 1.Desoye G, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. The human placenta in gestational diabetes mellitus. The insulin and cytokine network. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(Suppl 2):S120–126. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gude NM, Roberts CT, Kalionis B, King RG. Growth and function of the normal human placenta. Thromb Res. 2004;114:397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jansson T, Powell TL. Role of placental nutrient sensing in developmental programming. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;56:591–601. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3182993a2e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burton GJ, Yung HW, Murray AJ. Mitochondrial - Endoplasmic reticulum interactions in the trophoblast: Stress and senescence. Placenta. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiaratti MR, Malik S, Diot A, Rapa E, Macleod L, Morten K, Vatish M, Boyd R, Poulton J. Is Placental Mitochondrial Function a Regulator that Matches Fetal and Placental Growth to Maternal Nutrient Intake in the Mouse? PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wakefield SL, Lane M, Mitchell M. Impaired mitochondrial function in the preimplantation embryo perturbs fetal and placental development in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:572–580. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.087262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Visiedo F, Bugatto F, Sanchez V, Cozar-Castellano I, Bartha JL, Perdomo G. High glucose levels reduce fatty acid oxidation and increase triglyceride accumulation in human placenta. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;305:E205–212. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00032.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meng Q, Shao L, Luo X, Mu Y, Xu W, Gao C, Gao L, Liu J, Cui Y. Ultrastructure of Placenta of Gravidas with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Obstetrics and gynecology international. 2015;2015:283124. doi: 10.1155/2015/283124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muralimanoharan S, Maloyan A, Myatt L. Mitochondrial function and glucose metabolism in the placenta with gestational diabetes mellitus: role of miR-143. Clin Sci (Lond) 2016;130:931–941. doi: 10.1042/CS20160076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang AMT Shaoning, Tryggestad Jeanie B, Lyons Timothy J, Chernausek Steven D. Effects of Maternal Diabetes on PGC-1a Expression in Placenta: Role of microRNA-130b. Diabetes. 2016;(supplement) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang H, Ward WF. PGC-1alpha: a key regulator of energy metabolism. Adv Physiol Educ. 2006;30:145–151. doi: 10.1152/advan.00052.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Z, Puigserver P, Andersson U, Zhang C, Adelmant G, Mootha V, Troy A, Cinti S, Lowell B, Scarpulla RC, Spiegelman BM. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell. 1999;98:115–124. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80611-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez-Marcos PJ, Auwerx J. Regulation of PGC-1alpha, a nodal regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:884S–890. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.001917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baar K, Wende AR, Jones TE, Marison M, Nolte LA, Chen M, Kelly DP, Holloszy JO. Adaptations of skeletal muscle to exercise: rapid increase in the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1. FASEB J. 2002;16:1879–1886. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0367com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cannon B, Houstek J, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue. More than an effector of thermogenesis? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;856:171–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michael LF, Wu Z, Cheatham RB, Puigserver P, Adelmant G, Lehman JJ, Kelly DP, Spiegelman BM. Restoration of insulin-sensitive glucose transporter (GLUT4) gene expression in muscle cells by the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3820–3825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061035098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iacovelli J, Rowe GC, Khadka A, Diaz-Aguilar D, Spencer C, Arany Z, Saint-Geniez M. PGC-1alpha Induces Human RPE Oxidative Metabolism and Antioxidant Capacity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:1038–1051. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mele J, Muralimanoharan S, Maloyan A, Myatt L. Impaired mitochondrial function in human placenta with increased maternal adiposity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;307:E419–425. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00025.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inui M, Martello G, Piccolo S. MicroRNA control of signal transduction. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2010;11:252–263. doi: 10.1038/nrm2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tryggestad JB, Vishwanath A, Jiang S, Mallappa A, Teague AM, Takahashi Y, Thompson DM, Chernausek SD. Influence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus on Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cell microRNA. Clin Sci (Lond) 2016 doi: 10.1042/CS20160305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ventura-Clapier R, Garnier A, Veksler V. Transcriptional control of mitochondrial biogenesis: the central role of PGC-1alpha. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:208–217. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, Subramanian A, Sihag S, Lehar J, Puigserver P, Carlsson E, Ridderstrale M, Laurila E, Houstis N, Daly MJ, Patterson N, Mesirov JP, Golub TR, Tamayo P, Spiegelman B, Lander ES, Hirschhorn JN, Altshuler D, Groop LC. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34:267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang P, Liu C, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Shen P, Zhang J, Zhang CY. Free fatty acids increase PGC-1alpha expression in isolated rat islets. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1446–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu L, Sun G, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Chen X, Jiang X, Jiang X, Krauss S, Zhang J, Xiang Y, Zhang CY. PGC-1alpha is a key regulator of glucose-induced proliferation and migration in vascular smooth muscle cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang YC, Li Y, Wang XY, Zhang D, Zhang H, Wu Q, He YQ, Wang JY, Zhang L, Xia H, Yan J, Li X, Ying H. Circulating miR-130b mediates metabolic crosstalk between fat and muscle in overweight/obesity. Diabetologia. 2013;56:2275–2285. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2996-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagschal A, Najafi-Shoushtari SH, Wang L, Goedeke L, Sinha S, deLemos AS, Black JC, Ramirez CM, Li Y, Tewhey R, Hatoum I, Shah N, Lu Y, Kristo F, Psychogios N, Vrbanac V, Lu YC, Hla T, de Cabo R, Tsang JS, Schadt E, Sabeti PC, Kathiresan S, Cohen DE, Whetstine J, Chung RT, Fernandez-Hernando C, Kaplan LM, Bernards A, Gerszten RE, Naar AM. Genome-wide identification of microRNAs regulating cholesterol and triglyceride homeostasis. Nat Med. 2015;21:1290–1297. doi: 10.1038/nm.3980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bustamante J, Ramirez-Velez R, Czerniczyniec A, Cicerchia D, Aguilar de Plata AC, Lores-Arnaiz S. Oxygen metabolism in human placenta mitochondria. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2014;46:459–469. doi: 10.1007/s10863-014-9572-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lappas M, Hiden U, Desoye G, Froehlich J, Hauguel-de Mouzon S, Jawerbaum A. The role of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of gestational diabetes mellitus. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:3061–3100. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prabu P, Rome S, Sathishkumar C, Aravind S, Mahalingam B, Shanthirani CS, Gastebois C, Villard A, Mohan V, Balasubramanyam M. Circulating MiRNAs of 'Asian Indian Phenotype' Identified in Subjects with Impaired Glucose Tolerance and Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prats-Puig A, Ortega FJ, Mercader JM, Moreno-Navarrete JM, Moreno M, Bonet N, Ricart W, Lopez-Bermejo A, Fernandez-Real JM. Changes in circulating microRNAs are associated with childhood obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E1655–1660. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canto C, Auwerx J. PGC-1alpha, SIRT1 and AMPK, an energy sensing network that controls energy expenditure. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2009;20:98–105. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328328d0a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelstrup L, Hjort L, Houshmand-Oeregaard A, Clausen TD, Hansen NS, Broholm C, Borch-Johnsen L, Mathiesen E, Vaag AA, Damm P. DNA methylation and gene expression of PPARGC1A in muscle and fat biopsies from adult offspring of women with diabetes in pregnancy. Diabetologia. 2015;58:S58–S59. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.