Abstract

Decreases in serum bilirubin and albumin levels are associated with poorer prognoses in some types of cancer. Here, we examined the predictive value of serum bilirubin and albumin levels in 778 gastric cancer patients from a single hospital in China who were divided among prospective training and retrospective validation cohorts. X-tile software was used to identify optimal cutoff values for separating training cohort patients into higher and lower overall survival (OS) groups, based on total bilirubin (TBIL) and albumin levels. In univariate analysis, tumor grade and TNM stage were associated with OS. After adjusting for tumor grade and TNM stage, TBIL and albumin levels were still clearly associated with OS. These results were confirmed in the 299 patients in the validation cohort. A nomogram based on TBIL and albumin levels was more accurate than the TNM staging system for predicting prognosis in both cohorts. These results suggest that serum TBIL and albumin levels are independent predictors of OS in gastric cancer patients, and that an index that combines TBIL and albumin levels with the TNM staging system might have more predictive value than any of these measures alone.

Keywords: gastric cancer, bilirubin, albumin, prognosis, nomogram

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is the second most common malignant disease and cause of cancer-related death worldwide, especially in developing countries [1]. Predicting clinical outcomes for gastric cancer patients can be challenging due to genetic and geographically-dependent differences in incidence, stage at treatment, and patient prognosis [2]. However, accurate prediction of prognosis is crucial for selecting therapeutic strategies and for effective communication between doctors and gastric cancer patients.

Generally, prognostic evaluations in gastric cancer are based mainly on the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system. However, due to constraints associated with maintaining its simplicity and uniformity, the TNM staging system does not take into account many essential variables, including patient characteristics, laboratory test results, and treatments administered, that can influence the survival of gastric cancer patients [3]. The TNM staging system is therefore limited in its ability to assess survival in these patients, and survival predictions can vary widely for each gastric cancer stage [4]. Nomograms have been increasingly used to more accurately predict individualized patient outcomes in a variety of cancers. However, few nomograms have been developed that predict clinical outcomes for gastric cancer patients.

Serum bilirubin, which is an end product of heme metabolism, was not thought to serve any physiological function. Nevertheless, recent studies have demonstrated that serum bilirubin has potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer effects in colorectal cancer [5, 6]. The protective effects of serum bilirubin have been reported in lung cancer [7, 8], colorectal cancer [9], and breast cancer [10]. Additionally, decreased levels of albumin, a factor commonly used as an indicator of nutritional status, are associated with worse outcomes in gastric cancer patients [11].

Although they might improve prognostic predictions in gastric cancer, no measurements or indices that combine serum bilirubin and albumin levels have been developed. In this study, we examined whether serum bilirubin and albumin levels were predictive of survival outcomes in gastric cancer patients. We then evaluated the predictive value of a nomogram based on serum bilirubin and albumin levels in these patients.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics for the two patient cohorts are summarized in Table 1. A total of 352 men and 127 women were prospectively enrolled in the training cohort. Of these patients, 180 (37.6%) had distant metastasis and 275 (57.4%) received chemotherapy. During the follow-up period, 298 (62.2%) patients died (median follow-up, 1156 days). The median values for TBIL, DBIL, IDBIL, and albumin were 10.1 μmol/L, 3.6 μmol/L, 6.3 μmol/L, and 37.1 g/L, respectively. An additional 299 patients were retrospectively enrolled in the validation cohort. Pathologic TNM staging distributions varied widely; 31 (10.4%) individuals had early gastric cancer, and 72 (24.1%) had node negative disease. Two hundred six had died (median follow-up, 989 days) during the follow-up period.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics for training and validation cohort patients.

| Clinical characteristics | Training cohort | Validation cohort | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 65 (57-74) | 66 (57-74) | 0.756 |

| Gender (male) | 352 (73.5) | 220 (73.6) | 0.977 |

| Smoking | 110 (23.0) | 56 (18.7) | 0.161 |

| Drinking | 52 (10.9) | 59 (19.7) | 0.001 |

| Helicobator pylori | 261 (54.5) | 172 (57.5) | 0.407 |

| Tumor differentiation (well/moderate/poor) | 89/194/196 | 40/140/119 | 0.092 |

| pT stage (1/2/3/4) | 77/49/199/154 | 31/25/142/101 | 0.085 |

| pN stage (0/1/2/3) | 125/141/97/116 | 72/110/56/61 | 0.189 |

| Metastasis | 180 (37.6) | 127 (42.5) | 0.174 |

| Chemotherapy | 275 (57.4) | 163 (54.5) | 0.428 |

| Curative/palliative | 285/194 | 161/138 | 0.121 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 10.1 (7.1-14.6) | 9.9 (6.4-13.9) | 0.411 |

| DBIL (μmol/L) | 3.6 (2.5-5.2) | 3.5 (2.0-5.4) | 0.123 |

| IBIL (μmol/L) | 6.3 (4.3-9.4) | 6.2 (3.5-9.3) | 0.078 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 37.1 (34.1-40.5) | 37.2 (33.7-40.0) | 0.544 |

TBIL, Total bilirubin; DBIL, direct bilirubin; IBIL, indirect bilirubin.

Values are medians (interquartile range) or frequencies and percentages.

Patients received treatment for either curative or palliative purposes according to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Cancer Guidelines.

Data were analyzed using χ2 test or Mann-Whitney U test.

Associations between TBIL, DBIL, IBIL, and albumin levels and clinical characteristics

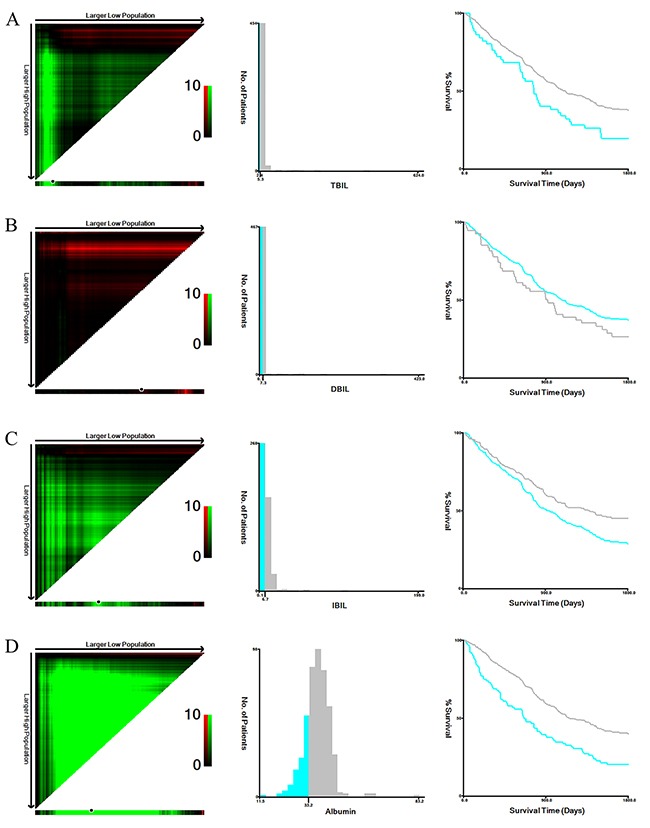

We first compared clinical characteristics of training and validation cohort patients. Patients in the two cohorts were similar with regard to all clinical characteristics except drinking (P<0.001) (Table 1), indicating that the cohorts were comparable. We then explored associations between TBIL, DBIL, IBIL, and albumin levels and clinical characteristics. X-tile software was used to determine the optimal cutoff values of 5.3 μmol/L for TBIL, 7.3μmol/L for DBIL, 6.7 μmol/L for IBIL, and 33.2 g/L for albumin based on OS in training cohort patients (Figure 1). Training cohort patients were then divided into high and low level groups based on these cutoffs. Lymph node metastasis (N2 and N3 stage) was more common in patients in the low TBIL group than in those in the high TBIL group (Table 2). In addition, markedly more patients in the high DBIL group had T4 and N3 stage disease compared to the low DBIL group (Table 3). T1 stage and N0 stage disease were more common in patients in the high IBIL group than in those in the low IBIL group (Table 4). Finally, patients in the high albumin group were younger and more likely to have T1-T2, N0, or M0 stage disease than those in low albumin group (Table 5). Similar results were obtained when validation cohort patients were divided into high and low level groups for each measure based on the same optimal cutoff values used for the training cohort (Table 2-5).

Figure 1. X-tile analyses of TBIL (A), DBIL (B), IBIL (C), and albumin (D) levels in training cohort gastric cancer patients.

X-tile plots for training cohort patients are shown in the left panels; black circles highlight the optimal cutoff values, which are also shown in histograms (middle panels). Kaplan-Meier plots are presented in right panels.

Table 2. Associations between TBIL level and clinical characteristics in training and validation cohort patients.

| Variable | TBIL group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training cohort | Validation cohort | |||||

| Low TBIL | High TBIL | P | Low TBIL | High TBIL | P | |

| Age | 63 (57-75) | 65 (58-74) | 0.779 | 66.5 (57-78) | 65 (57-74) | 0.173 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 36 (70.6) | 316 (73.8) | 0.620 | 41 (73.2) | 179 (73.7) | 0.945 |

| Female | 15 (29.4) | 112 (26.2) | 15 (26.8) | 64 (26.3) | ||

| Smoking | ||||||

| Never | 39 (76.5) | 330 (77.1) | 0.919 | 44 (78.6) | 199 (81.9) | 0.566 |

| Yes | 12 (23.5) | 98 (22.9) | 12 (21.4) | 44 (18.1) | ||

| Drinking | ||||||

| Never | 43 (84.3) | 384 (89.7) | 0.241 | 45 (80.4) | 195 (80.2) | 0.985 |

| Yes | 8 (15.7) | 44 (10.3) | 11 (19.6) | 48 (19.8) | ||

| Helicobator pylori | ||||||

| Negative | 21 (41.2) | 197 (46.0) | 0.511 | 25 (44.6) | 102 (42.0) | 0.716 |

| Positive | 30 (58.8) | 231 (54.0) | 31 (55.4) | 141 (58.0) | ||

| Differentiation | ||||||

| Well | 8 (15.7) | 81 (18.9) | 0.591 | 6 (10.7) | 34 (14.0) | 0.127 |

| Moderate | 24 (47.1) | 170 (39.7) | 21 (37.5) | 119 (49.0) | ||

| Poor | 19 (37.3) | 177 (41.4) | 29 (51.8) | 90 (37.0) | ||

| pT stage | ||||||

| T1 | 5 (9.8) | 72 (16.8) | 0.400 | 1 (1.8) | 30 (12.3) | 0.001 |

| T2 | 4 (7.8) | 45 (10.5) | 2 (3.6) | 23 (9.5) | ||

| T3 | 26 (51.0) | 173 (40.4) | 23 (41.1) | 119 (49.0) | ||

| T4 | 16 (31.4) | 138 (32.2) | 30 (53.6) | 71 (29.2) | ||

| pN stage | ||||||

| N0 | 10 (19.6) | 115 (26.9) | 0.017 | 14 (25.0) | 58 (23.9) | 0.043 |

| N1 | 12 (23.5) | 129 (30.1) | 12 (21.4) | 98 (40.3) | ||

| N2 | 19 (37.3) | 78 (18.2) | 14 (25.0) | 42 (17.3) | ||

| N3 | 10 (19.6) | 106 (24.8) | 16 (28.6) | 45 (18.5) | ||

| Metastasis | ||||||

| Absent | 30 (58.8) | 269 (62.9) | 0.575 | 27 (48.2) | 145 (59.7) | 0.117 |

| Present | 21 (41.2) | 159 (37.1) | 29 (51.8) | 98 (40.3) | ||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No | 28 (54.9) | 176 (41.1) | 0.060 | 30 (53.6) | 106 (43.6) | 0.178 |

| Yes | 23 (45.1) | 252 (58.9) | 26 (46.4) | 137 (56.4) | ||

| Treatments | ||||||

| Curative | 28 | 257 | 0.479 | 25 | 136 | 0.125 |

| Palliative | 23 | 171 | 31 | 107 | ||

TBIL, total bilirubin.

Values are medians (interquartile range) or frequencies and percentages.

Data were analyzed using χ2 test or Mann-Whitney U test.

Table 3. Associations between DBIL levels and clinical characteristics in training and validation cohort patients.

| Variable | DBIL group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training cohort | Validation cohort | |||||

| Low DBIL | High DBIL | P | Low DBIL | High DBIL | P | |

| Age | 65 (58-74) | 63 (54-74) | 0.598 | 66 (57-74) | 62 (52-75) | 0.429 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 308 (72.0) | 44 (86.3) | 0.029 | 197 (73.0) | 23 (79.3) | 0.663 |

| Female | 120 (28.0) | 7 (13.7) | 73 (27.0) | 7 (20.7) | ||

| Smoking | ||||||

| Never | 331 (77.3) | 38 (74.5) | 0.650 | 219 (81.1) | 24 (82.8) | 0.829 |

| Yes | 97 (22.7) | 13 (25.5) | 51 (18.9) | 5 (17.2) | ||

| Drinking | ||||||

| Never | 381 (89.0) | 46 (90.2) | 0.798 | 218 (80.7) | 22 (75.9) | 0.530 |

| Yes | 47 (11.0) | 5 (9.8) | 52 (19.3) | 7 (24.1) | ||

| Helicobator pylori | ||||||

| Negative | 193 (45.1) | 25 (49.0) | 0.595 | 116 (43.0) | 11 (37.9) | 0.602 |

| Positive | 235 (54.9) | 26 (51.0) | 154 (57.0) | 18 (62.1) | ||

| Differentiation | ||||||

| Well | 82 (19.2) | 7 (13.7) | 0.529 | 32 (11.9) | 8 (27.6) | 0.059 |

| Moderate | 174 (40.7) | 20 (39.2) | 128 (47.4) | 12 (41.4) | ||

| Poor | 172 (40.2) | 24 (47.1) | 110 (40.7) | 9 (31.0) | ||

| pT stage | ||||||

| T1 | 65 (15.2) | 12 (23.5) | 0.009 | 30 (11.1) | 1 (3.4) | 0.014 |

| T2 | 46 (10.7) | 3 (5.9) | 20 (7.4) | 5 (17.2) | ||

| T3 | 187 (43.7) | 12 (23.5) | 134 (49.6) | 8 (27.6) | ||

| T4 | 130 (30.4) | 24 (47.1) | 86 (31.9) | 15 (51.7) | ||

| pN stage | ||||||

| N0 | 112 (26.2) | 13 (25.5) | 0.005 | 69 (25.6) | 3 (10.3) | 0.003 |

| N1 | 135 (31.5) | 6 (11.8) | 104 (38.6) | 6 (20.7) | ||

| N2 | 86 (20.1) | 11 (21.6) | 49 (18.1) | 7 (24.1) | ||

| N3 | 95 (22.2) | 21 (41.2) | 48 (17.7) | 13 (44.8) | ||

| Metastasis | ||||||

| Absent | 273 (63.8) | 26 (51.0) | 0.074 | 157 (58.1) | 15 (51.7) | 0.506 |

| Present | 155 (36.2) | 25 (49.0) | 113 (41.9) | 14 (48.3) | ||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No | 183 (42.8) | 21 (41.2) | 0.829 | 118 (43.7) | 18 (62.1) | 0.059 |

| Yes | 245 (57.2) | 30 (58.8) | 152 (56.3) | 11 (37.9) | ||

| Treatments | ||||||

| Curative | 259 | 26 | 0.190 | 147 | 14 | 0.527 |

| Palliative | 169 | 25 | 123 | 15 | ||

DBIL, direct bilirubin.

Values are medians (interquartile range) or frequencies and percentages.

Data were analyzed using χ2 test or Mann-Whitney U test.

Table 4. Associations between IBIL levels and clinical characteristics in training and validation cohort patients.

| Variable | IBIL group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training cohort | Validation cohort | |||||

| Low IBIL | High IBIL | P | Low IBIL | High IBIL | P | |

| Age | 66 (59-76) | 64 (55-71) | 0.078 | 66 (57-75) | 64 (56-73) | 0.349 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 188 (72.3) | 164 (74.9) | 0.524 | 131 (77.1) | 89 (69.0) | 0.117 |

| Female | 72 (27.7) | 55 (25.1) | 39 (22.9) | 40 (31.0) | ||

| Smoking | ||||||

| Never | 203 (78.1) | 166 (75.8) | 0.555 | 139 (81.8) | 104 (80.6) | 0.802 |

| Yes | 57 (21.9) | 53 (24.2) | 31 (18.2) | 25 (19.4) | ||

| Drinking | ||||||

| Never | 233 (89.6) | 194 (88.6) | 0.718 | 133 (78.2) | 107 (82.9) | 0.311 |

| Yes | 27 (10.4) | 25 (11.4) | 37 (21.8) | 22 (17.1) | ||

| Helicobator pylori | ||||||

| Negative | 110 (42.3) | 108 (49.3) | 0.125 | 72 (42.4) | 55 (42.6) | 0.961 |

| Positive | 150 (57.7) | 111 (50.7) | 98 (57.6) | 74 (57.4) | ||

| Differentiation | ||||||

| Well | 44 (16.9) | 45 (20.5) | 0.593 | 28 (16.5) | 12 (9.3) | 0.069 |

| Moderate | 108 (41.5) | 86 (39.3) | 71 (41.8) | 69 (53.5) | ||

| Poor | 108 (41.5) | 88 (40.2) | 71 (41.8) | 48 (37.2) | ||

| pT stage | ||||||

| T1 | 28 (10.8) | 49 (22.4) | 0.006 | 10 (5.9) | 21 (16.3) | 0.013 |

| T2 | 26 (10.0) | 23 (10.5) | 15 (8.8) | 10 (7.8) | ||

| T3 | 115 (44.2) | 84 (38.4) | 79 (46.5) | 63 (48.8) | ||

| T4 | 91 (35.0) | 63 (28.8) | 66 (38.8) | 35 (27.1) | ||

| pN stage | ||||||

| N0 | 54 (20.8) | 71 (32.4) | 0.011 | 36 (21.2) | 36 (27.9) | 0.003 |

| N1 | 83 (31.9) | 58 (26.5) | 69 (40.6) | 41 (31.8) | ||

| N2 | 62 (23.8) | 35 (16.0) | 40 (23.5) | 16 (12.4) | ||

| N3 | 61 (23.5) | 55 (25.1) | 25 (14.7) | 36 (27.9) | ||

| Metastasis | ||||||

| Absent | 152 (58.5) | 147 (67.1) | 0.051 | 96 (56.5) | 76 (58.9) | 0.672 |

| Present | 108 (41.5) | 72 (32.9) | 74 (43.5) | 53 (41.1) | ||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No | 115 (44.2) | 89 (40.6) | 0.428 | 80 (47.1) | 56 (43.4) | 0.530 |

| Yes | 145 (55.8) | 130 (59.4) | 90 (52.9) | 73 (56.6) | ||

| Treatments | ||||||

| Curative | 150 | 135 | 0.380 | 88 | 73 | 0.407 |

| Palliative | 110 | 84 | 82 | 56 | ||

IBIL, indirect bilirubin.

Values are medians (interquartile range) or frequencies and percentages.

Data were analyzed using χ2 test or Mann-Whitney U test.

Table 5. Association between albumin levels and clinical characteristics in training and validation cohort patients.

| Variable | Albumin group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training cohort | Validation cohort | |||||

| Low Albumin | High Albumin | P | Low Albumin | High Albumin | P | |

| Age | 72 (63.5-78) | 64 (56-71) | <0.001 | 74 (64-78) | 64 (56-72) | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 71 (70.3) | 281 (74.3) | 0.414 | 50 (76.9) | 170 (72.6) | 0.489 |

| Female | 30 (29.7) | 97 (25.7) | 15 (23.1) | 64 (27.4) | ||

| Smoking | ||||||

| Never | 79 (78.2) | 290 (76.7) | 0.750 | 54 (83.1) | 189 (80.8) | 0.673 |

| Yes | 22 (21.8) | 88 (23.3) | 11 (16.9) | 45 (19.2) | ||

| Drinking | ||||||

| Never | 91 (90.1) | 336 (88.9) | 0.728 | 56 (86.2) | 184 (78.6) | 0.178 |

| Yes | 10 (9.9) | 42 (11.1) | 9 (13.8) | 50 (21.4) | ||

| Helicobator pylori | ||||||

| Negative | 48 (47.5) | 213 (56.3) | 0.114 | 23 (35.4) | 104 (44.4) | 0.191 |

| Positive | 53 (52.5) | 165 (43.7) | 42 (64.6) | 130 (55.6) | ||

| Differentiation | ||||||

| Well | 15 (14.9) | 74 (19.6) | 0.275 | 9 (13.8) | 31 (13.2) | 0.922 |

| Moderate | 38 (37.6) | 156 (41.3) | 29 (44.6) | 111 (47.4) | ||

| Poor | 48 (47.5) | 148 (39.2) | 27 (41.5) | 92 (39.3) | ||

| pT stage | ||||||

| T1 | 8 (7.9) | 69 (18.3) | <0.001 | 1 (1.5) | 30 (12.8) | <0.001 |

| T2 | 7 (6.9) | 42 (11.1) | 2 (3.1) | 23 (9.8) | ||

| T3 | 36 (35.6) | 163 (43.1) | 28 (43.1) | 114 (48.7) | ||

| T4 | 50 (49.5) | 104 (27.5) | 34 (52.3) | 67 (28.6) | ||

| pN stage | ||||||

| N0 | 15 (14.9) | 110 (29.1) | <0.001 | 9 (13.8) | 63 (26.9) | 0.042 |

| N1 | 23 (22.8) | 118 (31.2) | 27 (41.5) | 83 (35.5) | ||

| N2 | 30 (29.7) | 67 (17.7) | 18 (27.7) | 38 (16.2) | ||

| N3 | 33 (32.7) | 83 (22.0) | 11 (16.9) | 50 (21.4) | ||

| Metastasis | ||||||

| Absent | 42 (41.6) | 257 (68.0) | <0.001 | 23 (35.4) | 149 (63.7) | <0.001 |

| Present | 59 (58.4) | 121 (32.0) | 42 (64.6) | 85 (36.3) | ||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No | 50 (49.5) | 154 (40.7) | 0.114 | 36 (55.4) | 100 (42.7) | 0.070 |

| Yes | 51 (50.0) | 224 (59.3) | 29 (44.6) | 134 (57.3) | ||

| Treatments | ||||||

| Curative | 53 | 232 | 0.106 | 30 | 131 | 0.160 |

| Palliative | 48 | 146 | 35 | 103 | ||

Values are medians (interquartile range) or frequencies and percentages.

Data were analyzed using χ2 test or Mann-Whitney U test.

Prognostic significance of TBIL, DBIL, IBIL, and albumin

Five-year overall survival rates and univariate log-rank test results for clinical variables in the training and validation cohorts are shown in Table 6. Five-year OS was shorter in patients with low TBIL, IBIL, and albumin levels (P<0.01). Multivariate Cox regression analysis was then conducted for clinical features identified as significant in the univariate log-rank test. T, N, and M stages as well as TBIL and albumin levels were independently prognostic factors for OS in both the training and validation cohorts (Table 6).

Table 6. Univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic significance of serum bilirubin and albumin levels.

| Training cohort | Validation cohort | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||

| 5-year OS (%) | Log rank χ2 test | P | HR (95%CI) | P | 5-year OS (%) | Log rank χ2 test | P | HR (95%CI) | P | |

| Age | 3.543 | 0.060 | 2.379 | 0.121 | ||||||

| <65 years | 42.4 | 34.1 | ||||||||

| ≥65 years | 33.7 | 28.1 | ||||||||

| Gender | 1.552 | 0.213 | 0.361 | 0.548 | ||||||

| Male | 36.7 | 29.8 | ||||||||

| Female | 40.9 | 32.7 | ||||||||

| Smoking | 1.683 | 0.195 | 0.338 | 0.561 | ||||||

| Never | 35.7 | 31.2 | ||||||||

| Yes | 45.0 | 27.8 | ||||||||

| Drinking | 0.949 | 0.330 | 0.580 | 0.446 | ||||||

| Never | 37.1 | 29.7 | ||||||||

| Yes | 43.4 | 34.2 | ||||||||

| Helicobator pylori | 1.521 | 0.218 | 0.001 | 0.972 | ||||||

| Negative | 34.2 | 28.8 | ||||||||

| Positive | 40.8 | 31.8 | ||||||||

| Differentiation | 33.100 | <0.001 | 18.475 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Well | 64.0 | Reference | 57.7 | Reference | ||||||

| Moderate | 34.7 | 1.028 (0.710-1.577) | 0.692 | 30.7 | 1.442 (0.819-2.539) | 0.205 | ||||

| Poor | 29.1 | 1.147 (0.600-1.668) | 0.823 | 22.4 | 1.617 (0.924-2.828) | 0.092 | ||||

| pT stage | 153.793 | <0.001 | 96.193 | <0.001 | ||||||

| T1 | 87.0 | Reference | 80.6 | Reference | ||||||

| T2 | 66.0 | 1.022 (0.962-3.605) | 0.068 | 42.9 | 1.896 (1.232-2.833) | 0.011 | ||||

| T3 | 30.7 | 1.920 (1.041-4.224) | 0.012 | 32.1 | 1.937 (1.181-3.280) | 0.003 | ||||

| T4 | 13.5 | 2.446 (1.253-5.233) | <0.001 | 9.9 | 2.341 (1.214-3.676) | <0.001 | ||||

| pN stage | 190.446 | <0.001 | 58.345 | <0.001 | ||||||

| N0 | 80.2 | Reference | 63.9 | Reference | ||||||

| N1 | 36.6 | 1.387 (1.056-2.900) | 0.043 | 29.7 | 1.735 (1.013-2.973) | 0.045 | ||||

| N2 | 17.5 | 2.006 (1.310-4.018) | <0.001 | 18.0 | 2.150 (1.182-3.911) | 0.012 | ||||

| N3 | 10.3 | 3.043 (1.085-6.364) | <0.001 | 9.8 | 2.609 (1.451-4.693) | <0.001 | ||||

| Metastasis | 160.020 | <0.001 | 144.813 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Absent | 53.7 | Reference | 45.5 | Reference | ||||||

| Present | 11.6 | 1.859 (1.254-2.706) | <0.001 | 7.8 | 2.168 (1.407-3.154) | <0.001 | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 0.109 | 0.742 | 0.168 | 0.682 | ||||||

| No | 40.7 | 30.2 | ||||||||

| Yes | 37.8 | 30.9 | ||||||||

| Treatments | 98.528 | <0.001 | 120.314 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Curative | 50.6 | Reference | 42.7 | Reference | ||||||

| Palliative | 15.0 | 1.556 (1.160-2.011) | <0.001 | 9.4 | 2.590 (1.423-3.154) | <0.001 | ||||

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 7.613 | 0.006 | 31.756 | <0.001 | ||||||

| ≤5.3 | 23.5 | Reference | 7.9 | Reference | ||||||

| >5.3 | 39.5 | 0.688 (0.491-0.959) | 0.022 | 36.1 | 0.794 (0.552-0.951) | 0.032 | ||||

| DBIL (μmol/L) | 2.204 | 0.138 | 0.097 | 0.756 | ||||||

| ≤7.3 | 38.8 | 30.0 | ||||||||

| >7.3 | 29.4 | 36.1 | ||||||||

| IBIL (μmol/L) | 9.818 | 0.002 | 5.099 | 0.024 | ||||||

| ≤6.7 | 30.8 | Reference | 25.0 | Reference | ||||||

| >6.7 | 46.1 | 0.994 (0.792-1.290) | 0.860 | 37.9 | 0.915 (0.662-1.264) | 0.590 | ||||

| Albumin (g/L) | 23.351 | <0.001 | 17.036 | <0.001 | ||||||

| ≤33.2 | 22.8 | Reference | 20.2 | Reference | ||||||

| >33.2 | 41.8 | 0.685 (0.520-0.890) | 0.002 | 33.4 | 0.774 (0.554-0.961) | 0.034 | ||||

TBIL, Total bilirubin; DBIL, direct bilirubin; IBIL, indirect bilirubin. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Nomogram for predicting gastric cancer outcomes

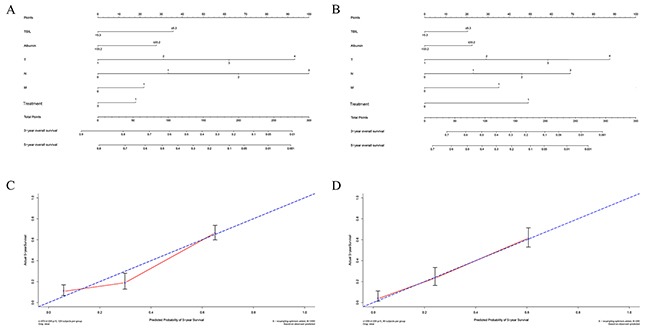

To further assess the predictive ability of TBIL and albumin in gastric cancer patients, we used a nomogram based on the results of the univariate analyses to predict 5-year overall survival rates. Tumor grade, T, N, and M stage, treatment approach, and TBIL, IBIL, and albumin level were included in the nomogram for both the training (Figure 2A) and validation (Figure 2B) cohorts. The predictive models for both cohorts showed that treatment with palliative operation and advanced T, N, and M stage were poor prognostic indicators, while high TBIL and albumin levels were favorable factors. These findings were similar to those obtained previously in the multivariate Cox regression analyses (Table 6). Calibration curves for the nomogram in both cohorts revealed that the predicted 5-year OS values were similar to the actual 5-year OS (Figure 2C and 2D).

Figure 2. Nomogram for predicting gastric cancer outcomes.

The sum of the points assigned to each factor by the nomogram is shown at the top of scale. Total point values were used to predict 5-year probability of death in the lowest scale. The c-indexes values for the training cohort (A) and the validation cohort (B) are 0.762 and 0.744, respectively. Calibration curves for 5-year OS, which are indicative of predictive accuracy, for the training cohort (C) and the validation cohort (D). The 45-degree reference line represents a perfect match between observed and predicted values.

We then compared the predictive accuracy of the nomogram to that of the TNM staging system (T, N, and M stage only) in the training and the validation cohorts using Harrell's c-index. The Harrell's c-index values for the nomogram in the training and the validation cohorts were 0.774 and 0.760, respectively, compared to 0.727 and 0.702, respectively, for the TNM staging system. Collectively, the predictive accuracy of the nomogram based on TBIL and albumin levels was better than that of the TNM staging system in both patient cohorts (P<0.01).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we confirmed the prognostic significance of serum bilirubin and albumin levels and, to our knowledge, demonstrated for the first time that elevated pre-treatment levels of these factors were positive prognostic factors for survival in gastric cancer. Elevated TBIL and albumin levels were associated with tumor progression and acted as protective prognostic factors in both training and validation cohort gastric cancer patients. Our nomogram also confirmed the prognostic significance of TBIL and albumin in gastric cancer patients.

Bile acid, which is the end product of cholesterol breakdown, exists in three forms in peripheral blood: TBIL, DBIL, and IBIL. Due to its anti-inflammation, antioxidant, and antiproliferation effects, bilirubin acts as a protective factor against carcinogenesis [12]. Decreased serum bilirubin is associated with an increased risk of cancer and with poorer outcomes [7]. Li et al. demonstrated that non-small cell lung cell cancer patients with higher pretreatment bilirubin levels had longer OS, DFS, and DMFS than those with lower levels [8]. Zhang and colleagues also found that high DBIL was strongly associated with worse outcomes after surgery in colorectal cancer patients with stage II and stage III disease in a retrospective study [9]; subsequent studies confirmed these results [13, 14]. However, the association between serum bilirubin levels and clinical outcomes in gastric cancer had not been examined. Here, we found that decreased serum TBIL was associated with advanced gastric cancer and poor prognosis, as is the case in other types of cancer [8, 9, 15]. Although training and validation cohort patients in our study differed with regard to drinking behavior, correlation analysis revealed no association between drinking status and serum bilirubin and albumin levels. Furthermore, serum TBIL and albumin were independent prognostic indicators regardless of drinking status both in the training and the validation cohorts. Taken together, these results suggest that serum bilirubin may have predictive value in gastric cancer.

Serum albumin, which is commonly used to evaluate an individual's nutritional status, also has antioxidant effects and acts as a transporter of key nutrients. Serum albumin levels fall sharply in patients with advanced cancer due to malnutrition and systemic inflammatory responses to malignancy [16]. Malnutrition can also cause a series of detrimental clinical effects and thus reduce treatment response. Previous studies have assessed the association between serum albumin and survival in gastric cancer patients [17, 18]. Liu et al. reported that serum albumin was an independent prognostic factor for worse outcomes in 1320 gastric cancer patients after curative resection [19]. In a separate study of 320 gastric cancer patients, Liu et al. found that preoperative albumin, BMI, and triglyceride levels were more accurate for predicting survival than the TNM system [20]. Our findings strongly suggest that low serum albumin levels are a prognostic indicator of poor outcome in gastric cancer patients, which is consistent with previous findings for other malignancies [21, 22].

Although individual serum markers are useful prognostic factors in studies of cancer patients, single markers may not be adequate for predicting survival in a clinical setting. Combining several markers in a single index may improve their predictive power [23–25], and nomograms are a useful method for combining clinical characteristics to improve survival predictions for individual patients. In the current study, we constructed a nomogram to predict survival in training and validation cohort gastric cancer patients based on several clinical characteristics. The nomogram accurately predicted 5-year overall survival in the training and validation cohorts; Harrell's c-indexes confirmed the accuracy of these predictions. Furthermore, serum TBIL and albumin levels were incorporated into the nomogram using a stepwise algorithm, and the predictive ability of the nomogram was confirmed using calibration curves. Additionally, a comparison of the predictive abilities of the constructed nomogram and the TNM staging system revealed that the nomogram was superior to TNM in both cohorts.

A major strength of this study is that it involved a relatively large number of gastric cancer patients undergoing treatment at a single center and that it included both prospective and retrospective cohorts. However, external validation studies should be performed to determine whether our results are applicable in other patient populations [26]. Another strength of this study is the use of X-tile software, which is a robust graphical tool [27], to determine the optimal cutoff values for serum bilirubin and albumin levels. However, some limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. For example, only pretreatment serum bilirubin and albumin levels were included in the present analyses, and it is possible that dynamic changes in serum bilirubin and albumin levels during the course of treatment might also influence outcomes in gastric cancer patients.

In summary, in this study of 778 gastric cancer patients, we found that a nomogram based on serum TBIL and albumin levels was more accurate than the TNM staging system in predicting survival. These findings suggest that serum TBIL and albumin levels in combination might improve outcome predictions for gastric cancer patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

The patients involved in this study were divided among two cohorts. The prospective training cohort consisted of 479 patients who underwent surgical resection or chemotherapy at the Nanjing First Hospital, Nanjing Medical University between January 2010 and November 2012. The retrospective validation cohort consisted of 299 patients who underwent surgical resection or chemotherapy at the same institution between January 2006 and December 2009. All individuals were diagnosed with biopsy-proven gastric adenocarcinoma. Patients who died within 30 days of surgery or who received preoperative antitumor treatment were excluded. Patients with tumors that invaded the biliary tract were also excluded due to the resulting elevation of serum bilirubin levels. All individuals received either open or laparoscopic surgery for either curative or palliative purposes according to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Cancer Guidelines [28]. Detailed clinical characteristics were collected before cancer treatment. Individuals were restaged according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system.

Regular follow-ups, which occurred every 3 months for the first 2 years and then every 6 months for 3 more years, began after the date of treatment and continued until September 30, 2016 or until patient death. Routine examination, gastroscopy, and imaging were performed at every visit. The follow-up period ranged from 91 to 3535 days, with a median of 1026 days. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nanjing First Hospital. Informed consent for use of their data was obtained from training cohort patients because of the prospective nature of the study.

Detection of serum bilirubin and albumin

Blood samples were collected from patients and serum was separated by centrifugation. Serum albumin levels were measured using a Roche Modular D/P automated analyzer (Roche, USA). Serum bilirubin levels were determined using the vanadium oxidation method.

Statistical analysis

Data assessment was performed using SPSS 20.0 version (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and R 3.3.1 software (Institute for Statistics and Mathematics, Vienna, Austria). First, optimal cutoff values for total bilirubin (TBIL), direct bilirubin (DBIL), indirect bilirubin (IBIL), and albumin levels were determined using X-tile 3.6.1 software (Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA) [27]. Differences between high- and low-level group patients were evaluated using the χ2 test or Mann-Whitney U test. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier curve and log-rank test. Significant prognostic predictors from the survival analysis were included in a multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model. The nomogram for significant factors associated with 5-year overall survival (OS) was constructed using R software via a stepwise algorithm, and Harrell's concordance index (c-index) was used to compare the performance of the nomogram to that of the TNM staging system. A calibration curve comparing observed outcomes to predicted outcomes was generated to further evaluate the nomogram's accuracy in predicting prognosis. P values of less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants from the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 81472027, 81501820) to SKW and YQP, the Jiangsu Provincial Medical Youth Talent to BSH (QNRC2016066) and YQP (QNRC2016074), the Nanjing Medical Science and Technique Development Foundation to BSH (No. JQX13003), and the Nanjing Medical University Science and Technique Development Foundation Project to ZLN (No. 2014NJMU038) and HLS (No. 2015NJMUZD049).

Authors’ contributions

HLS and SKW participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. YQP, KL, HXP, TX, XXC, XXH, ZJW and DW collected patient information and prepared figures. BSH and ZLN conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:115–32. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartgrink HH, Jansen EP, van Grieken NC, van de Velde CJ. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2009;374:477–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60617-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGhan LJ, Pockaj BA, Gray RJ, Bagaria SP, Wasif N. Validation of the updated 7th edition AJCC TNM staging criteria for gastric adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:53–61. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1707-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dikken JL, van de Velde CJ, Gonen M, Verheij M, Brennan MF, Coit DG. The New American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union Against Cancer staging system for adenocarcinoma of the stomach: increased complexity without clear improvement in predictive accuracy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2443–51. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2403-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiraskova A, Novotny J, Novotny L, Vodicka P, Pardini B, Naccarati A, Schwertner HA, Hubacek JA, Puncocharova L, Smerhovsky Z, Vitek L. Association of serum bilirubin and promoter variations in HMOX1 and UGT1A1 genes with sporadic colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:1549–55. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zucker SD, Horn PS, Sherman KE. Serum bilirubin levels in the U.S. population: gender effect and inverse correlation with colorectal cancer. Hepatology. 2004;40:827–35. doi: 10.1002/hep.20407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horsfall LJ, Rait G, Walters K, Swallow DM, Pereira SP, Nazareth I, Petersen I. Serum bilirubin and risk of respiratory disease and death. JAMA. 2011;305:691–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li N, Xu M, Cai MY, Zhou F, Li CF, Wang BX, Ou W, Wang SY. Elevated serum bilirubin levels are associated with improved survival in patients with curatively resected non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39:763–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Q, Ma X, Xu Q, Qin J, Wang Y, Liu Q, Wang H, Li M. Nomograms incorporated serum direct bilirubin level for predicting prognosis in stages II and III colorectal cancer after radical resection. Oncotarget. 2016 Aug;19 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11424. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ching S, Ingram D, Hahnel R, Beilby J, Rossi E. Serum levels of micronutrients, antioxidants and total antioxidant status predict risk of breast cancer in a case control study. J Nutr. 2002;132:303–6. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta D, Lis CG. Pretreatment serum albumin as a predictor of cancer survival: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr J. 2010;9:69. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-9-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marnett LJ. Oxyradicals and DNA damage. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:361–70. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao C, Fang L, Li JT, Zhao HC. Significance and prognostic value of increased serum direct bilirubin level for lymph node metastasis in Chinese rectal cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:2576–84. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i8.2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu QQ, Qiu H, Zhang MS, Hu GY, Liu B, Huang L, Liao X, Li QX, Li ZH, Yuan XL. Predictive effects of bilirubin on response of colorectal cancer to irinotecan-based chemotherapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:4250–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i16.4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X, Meng QH, Ye Y, Hildebrandt MA, Gu J, Wu X. Prognostic significance of pretreatment serum levels of albumin, LDH and total bilirubin in patients with non-metastatic breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36:243–8. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeun JY, Kaysen GA. Factors influencing serum albumin in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:S118–25. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(98)70174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crumley AB, Stuart RC, McKernan M, McMillan DC. Is hypoalbuminemia an independent prognostic factor in patients with gastric cancer? World J Surg. 2010;34:2393–8. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0641-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen XL, Xue L, Wang W, Chen HN, Zhang WH, Liu K, Chen XZ, Yang K, Zhang B, Chen ZX, Chen JP, Zhou ZG, Hu JK. Prognostic significance of the combination of preoperative hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet in patients with gastric carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. Oncotarget. 2015;6:41370–82. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X, Qiu H, Liu J, Chen S, Xu D, Li W, Zhan Y, Li Y, Chen Y, Zhou Z, Sun X. A Novel Prognostic Score, Based on Preoperative Nutritional Status, Predicts Outcomes of Patients after Curative Resection for Gastric Cancer. J Cancer. 2016;7:2148–56. doi: 10.7150/jca.16455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu BZ, Tao L, Chen YZ, Li XZ, Dong YL, Ma YJ, Li SG, Li F, Zhang WJ. Preoperative Body Mass Index, Blood Albumin and Triglycerides Predict Survival for Patients with Gastric Cancer. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Win T, Sharples L, Groves AM, Ritchie AJ, Wells FC, Laroche CM. Predicting survival in potentially curable lung cancer patients. Lung. 2008;186:97–102. doi: 10.1007/s00408-007-9067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma R, Hook J, Kumar M, Gabra H. Evaluation of an inflammation-based prognostic score in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:251–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boonpipattanapong T, Chewatanakornkul S. Preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen and albumin in predicting survival in patients with colon and rectal carcinomas. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:592–5. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200608000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deng Q, He B, Liu X, Yue J, Ying H, Pan Y, Sun H, Chen J, Wang F, Gao T, Zhang L, Wang S. Prognostic value of pre-operative inflammatory response biomarkers in gastric cancer patients and the construction of a predictive model. J Transl Med. 2015;13:66. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0409-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deng Q, He B, Gao T, Pan Y, Sun H, Xu Y, Li R, Ying H, Wang F, Liu X, Chen J, Wang S. Up-regulation of 91H promotes tumor metastasis and predicts poor prognosis for patients with colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ouldamer L, Bendifallah S, Chas M, Boivin L, Bedouet L, Body G, Ballester M, Darai E. Intrinsic and extrinsic flaws of the nomogram predicting bone-only metastasis in women with early breast cancer: An external validation study. Eur J Cancer. 2016;69:102–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Camp RL, Dolled-Filhart M, Rimm DL. X-tile: a new bio-informatics tool for biomarker assessment and outcome-based cut-point optimization. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7252–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3) Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113–23. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]