Abstract

Many older adult immigrants in the US, including Hmong older adults, have limited English proficiency (LEP), and cannot read or have difficulty reading even in their first language (non-literate [NL]). Little has been done to identify feasible data collection approaches to enable inclusion of LEP or NL populations in research, limiting knowledge about their health. This study’s purpose was to test the feasibility of culturally and linguistically adapted audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) with color-labeled response categories and helper assistance (ACASI-H) for collection of health data with Hmong older adults. Thirty dyads (older adult and a helper) completed an ACASI-H survey with 13 health questions and a face-to-face debriefing interview. ACASI-H survey completion was video-recorded and reviewed with participants. Video review and debriefing interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Directed and conventional content analyses were used to analyze the interviews. All respondents reported that ACASI-H survey questions were consistent with their health experience. They lacked computer experience and found ACASI-H’s interface user-friendly. All but one whose helper provided translation used the pre-recorded Hmong oral translation. Some Hmong older adults struggled with the color labeling at first, but helpers guided them to use the colors correctly. All dyads liked the color-labeled response categories and confirmed that a helper was necessary during the survey process. Findings support use of oral survey question administration with a technologically competent helper and color-labeled response categories when engaging LEP older adults in health-related data collection.

Keywords: Hmong, low literacy, audio-computer-self-interviewing, visual aids, research methods, data collection

More than four million foreign-born older adults live in the US (Population Reference Bureau [PRB], 2013), increasing from 2.7 million in 1990 to 4.6 million in 2010, and the number continues to grow (PRB, 2013). The majority are from Latin America (38%) and Asia (29%; PRB, 2013) and most have limited English proficiency (LEP; PRB, 2013), defined as an inability to speak or read English well (Whatley & Batalova, 2013). Despite rapid growth in the number of foreign-born older adults, little is known about their health status or service use, which is due at least in part to data collection difficulties (Frayne, Burns, Hardt, Rosen, & Moskowitz, 1996; Gayet-Ageron, Agoritsas, Schiesari, Kolly, & Perneger, 2011). As it is a national and international goal to reduce social and ethnic health inequalities (Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2013; World Health Organization [WHO], 2009), there is a need for reliable data to monitor the health status and behavior of LEP ethnic minorities. Little is known about data collection methods that could maximize response rates and data quality in this population. Securing participation and obtaining reliable information from these groups requires culturally appropriate data collection tools and techniques.

LEP minority groups are poorly represented in research (Frayne, Burns, Hardt, Rosen, & Moskowitz, 1996; Gayet-Ageron et al, 2011), as “English proficiency” is a common inclusion criterion (Frayne et al., 1996). Link and colleagues (2006) assessed the effects of race, ethnicity, and linguistic isolation on the rate of participation in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, a federal government survey that collects state data about US residents regarding health-related risk behaviors, chronic health conditions, and the use of preventive services. They reported that poor English proficiency was associated with the lowest rates of participation (Link et al., 2006). Gayet-Ageron and colleagues (2011) found limited language proficiency to be one of the top five barriers to participation in mail surveys.

LEP older adults are from collectivist cultures, where family members are highly interdependent and where the group is the unit of survival (Chen & West, 2008). LEP older adults often live in multigenerational households (Gurak & Kritz, 2010) and rely on their adult children to communicate with people outside their community or to make decisions (Casado & Leung, 2002; Wilmoth, 2001). However, younger family members who appear to be fluent in both their native language and in English may actually have limited literacy (e.g., cannot read or write, miss nuances) in their native language (United States Census Bureau, 2015), thus possibly affecting the accuracy of translations. We were unable to find any research examining data collection methods for LEP older adults that adapted the data collection process to accommodate these language limitations or that encouraged the active participation of older adults. Therefore, it is critical for researchers to develop a data collection tool that acknowledges and accommodates differences in language proficiency between younger family helpers and older adults and that supports the active participation of the older adults.

Rarely acknowledged is the further complication of collecting data from people generally unfamiliar with written language. Currently, 757 million people worldwide aged 15 and older are illiterate (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2016). Many of those who are illiterate are older and come from oral cultures (UNESCO, 2016), and it is important to develop data collection strategies that do not exclude them. Researchers have not examined how to promote research participation in non-literate (NL) or oral cultures, such as the Hmong culture (Thao, 2006). The written Hmong language was created in 1952 and is unfamiliar to most older Hmong (Duffy, 2007). In the US, 90% of older Hmong adults have LEP (National Asian Pacific Center on Aging, 2014) and are NL (Duffy, 2007). Consequently, even Hmong language written materials are indecipherable for older Hmong adults. In both research and practice settings, these individuals rely on translators who are often family members (Ryan, 2013; Yeo & Gallager-Thompson, 2013). By contrast, younger Hmong tend to be proficient in English and comfortable with technology (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008).

The Hmong live in small, tight communities where everyone can trace their family lines. There is a strong sense of family bonding. Both immediate and extended family members are very involved in each other’s lives, and everyone is involved in each other’s care. Therefore, to improve participation and elicit responses from LEP Hmong and other LEP older adults, researchers must develop effective data collection modes and tools to effectively communicate with LEP participants and accommodate the different language proficiency levels of older Hmong and younger family members who are likely to be helping them.

One data collection mode, audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI), has been increasingly used for research with low-literacy populations (Estes et al., 2010; Minnis et al., 2007; Reichmann et al., 2010). This oral delivery mode of data collection allows self-administration with low-literacy populations. ACASI can be delivered in multiple languages or dialects and improves the quality of behavioral health data gathering, reduces interviewer bias, standardizes question administration, and eliminates skip pattern errors (Jarlais et al., 1999). Different types of ACASI have been used in research, including telephone ACASI (Cooley et al., 2001; Villarroel et al., 2006) and color-coded ACASI (Bhatnagar, Brown, Saravanamurthy, Kumar, & Detels, 2013; Kauffman & Kauffman, 2011), but these modes of ACASI were developed for low-literate individuals and not for LEP or NL respondents.

To address the identified gaps in culturally appropriate data collection methods for LEP and NL older adults, we developed a data collection tool that could promote survey participation for this group. We examined the feasibility and usability of ACASI-H, including pre-recorded oral translation, color-labeled response categories, and a helper. The data collection tool can accommodate people who live in multigenerational households and receive assistance from younger family members whose language proficiency may differ from that of the older people. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to test the feasibility of a culturally and linguistically adapted ACASI with Hmong older adults in a natural setting.

Adapting ACASI for a Limited-Literacy Collectivist Culture

In addressing literacy barriers, Kauffman and Kauffman (2011) developed and used a color-coded ACASI component, where participants successfully responded using a separate customized data entry device with seven color-coded keypads. While this color-coded ACASI method was effective, it may not be practical for people without access to a separate customized data entry keypad with color-coded keys, which is not a part of computers in home settings. In addition, we found no studies on the effect of color-coded response categories in survey research. Our adaptation of the data collection mode, the audio computer-assisted self-interviewing with color-labeled response categories and helper assistance (ACASI-H), was designed to collect health data from people who cannot read in either English or in their native language, including people from oral cultures.

Two adaptations were made to the original ACASI system, as shown in Table 1. First, a helper who routinely assists the older adult with English documents was formally included. The inclusion of a helper was selected as a strategy compatible with the Hmong’s collectivist culture (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). Different from individualistic cultures, older adults from collectivist cultures often confer with family as opposed to strangers before answering questions (Chen, Lee, & Stevenson, 1995). Second, to facilitate communication, there was a simultaneous spoken presentation (pre-recoded oral translation) in the Hmong language, written text in English, and color coding corresponding to response items. The system allowed all participants to use their communication mode of choice (spoken Hmong with corresponding color coding, written English and response options, or spoken Hmong combined with written English response items). Thus, ACASI-H was designed to accommodate any combination of language proficiency.

Table 1.

Comparison of Original Audio-Computer-Assisted Self-interviewing (ACASI) with Color Coding and ACASI with Color Coding and Helper Assistance (ACASI-H)

| Original ACASI | Adapted ACASI-H | Justification for Adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| Recorded audio survey questions and corresponding text in the language of the participants | Recorded audio survey in Hmong language and corresponding text in English | Hmong older adults are not literate in Hmong and English. Helpers are fluent in Hmong and English but cannot read or write in Hmong. The corresponding English text allows helpers to assist the Hmong older adults in selecting appropriate responses and to confirm their responses. |

| Response categories in the participant’s language on screen, or response categories linked to colors indicated on stickers on keyboard keys | Response categories in English and color-labeled response categories band above English text on the screen | To accommodate the Hmong participants’ inability to read either Hmong or English and facilitate communication between the helper and the Hmong older adult. |

| Each question presented on a separate screen | Each question presented on a separate screen | |

| Use keyboard, mouse, and headphones to advance through the survey | Use keyboard, mouse, and speaker to advance through the survey | A speaker phone was used to allow elder and helper to listen to the question at the same time. |

| Self-administered | Helper assist | Simulate a natural environment in Hmong collectivist culture |

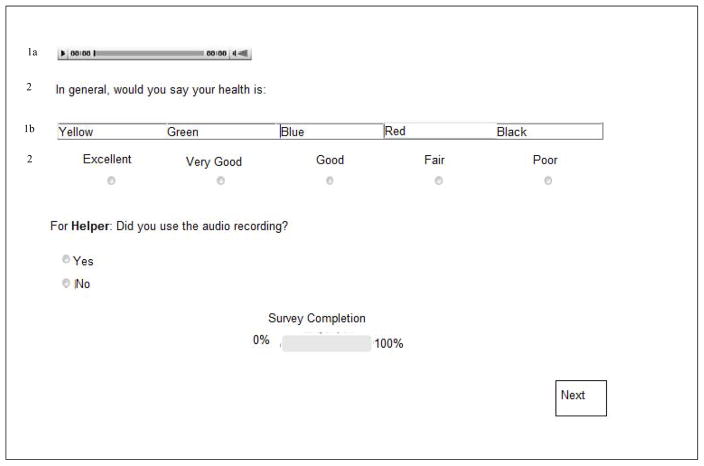

As seen in Figure 1, written response categories were labeled with colors in a bar above the written English text response options on the screen. For example, the pre-recorded oral translation says, “In general, would you say your health is: excellent (mark yellow), very good (mark green), good (mark blue), fair (mark red), or poor (mark black).” The corresponding English text allows helpers to assist the Hmong older adults in selecting appropriate responses and to confirm their responses, regardless of response option used. In this paper we report on the feasibility and usability of ACASI-H, including the pre-recorded oral translation color-labeled response categories, and the effectiveness of having a helper with differing language proficiency.

Figure 1.

Presentation of Audio Computer Assisted Self-interviewing with Color-Coding and Helper Assistance on Laptop Screen

Note: This is a screen shot of what the dyad (older adult and a helper) see on their laptop screen. On the screen, there are three presentations: (a) a pre-recorded oral Hmong translation for the elder (spoken Hmong; numbered 1a at the top of the screen); (b) is the original question written in English text for the helper (numbered 2 on the screen); and (c) is the colored band above the written English response categories text designed for the elder (numbered 1b). Each response is linked with a color as seen in this visual. For example, excellent is link with yellow; very good is link with green; good is link with blue; fair is linked with red; and poor is linked with black. When the dyad plays the oral translation, it reads in Hmong: “In general would you say your health is excellent mark yellow, very good mark green, good mark blue, fair mark red, or poor mark black.”

Methods

Design

We used a cross-sectional design to test the feasibility of ACASI-H in a natural setting. A convenience sample of 30 Hmong dyads (older adult and a helper) was recruited from two community centers in a Midwestern state. This study was approved by the Minimal Risk Health Sciences Institutional Review Board of the University of Wisconsin.

Sample

The target population included Hmong older adults and helpers. Eligibility criteria were being 50 or older, self-identifying as Hmong, and the availability of a usual helper. Inclusion criteria for the helpers were age 18 years or older, self-identifying as able to read and understand English, being identified by the older participant as routinely helping them with English documents, and being comfortable with using the Internet. Both members of the dyad must agree to the ACASI-H interview and a face-to-face debriefing.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited during senior program sessions at two predominantly Hmong community centers in Wisconsin and by word of mouth. The researchers attended scheduled senior program sessions and provided oral descriptions of the study’s purpose and procedures. This type of community-based approach is consistent with Hmong culture, as Hmong prefer to discuss and learn from each other in groups (Lor & Bowers, 2014). Word of mouth also was used, encouraging participating Hmong older adults to recruit other participants. Interested Hmong community members provided names and phone numbers to the researcher. In follow-up telephone calls, potential participants were asked: “Is there someone you generally go to for help in completing forms who is able to read in English?” Those who answered “yes” were invited to participate. Those who answered “no” were excluded.

Participants

Thirty dyads (30 Hmong older adults; 30 helpers) participated in the study. Twenty of the 30 (67%) completed the survey in their homes and 10 (33%) at a community center. The majority of Hmong older adult participants were female, married, with no formal education in the US, and had lived in the US for an average of 23 years (Table 2). The majority of Hmong older adults did not read Hmong well or at all, and did not write Hmong well or at all. The helpers were mostly female with a mean age of 29.3 (range 18–54), with most having between one and three years of college education (Table 3) and had lived a mean of 19.14 years in the US.

Table 2.

Demographic of Hmong Older Adults (N=30)

| Variables | n (%) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 22 (73.33) | |

| Male | 8 (26.67) | |

| Range of Age | 47a–77 | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 18 (60.00) | |

| Divorced | 3 (10.00) | |

| Widowed | 7 (23.33) | |

| Separated | 1 (3.33) | |

| Never been married | 0 (0.00) | |

| Years of Education in US | ||

| 0 | 21 (75.00) | |

| 1 | 3 (10.71) | |

| 2 | 1 (3.57) | |

| 4 | 1 (3.57) | |

| 7 | 2 (7.14) | |

| Years Lived in US | 9–36 | |

| How well do you read Hmong? | ||

| Not at all | 21 (70.00) | |

| Not well | 2 (7.00) | |

| Well | 4 (13.00) | |

| Very well | 3 (10.00) | |

| How well do you write Hmong? | ||

| Not at all | 23 (77.00) | |

| Not well | 3 (10.00) | |

| Well | 3 (10.00) | |

| Very well | 1 (3.00) | |

| How well do you read English? | ||

| Not at all | 26 (87.00) | |

| Not well | 3 (10.00) | |

| Well | 1 (3.00) | |

| Very well | 0 (0.00) | |

| How well do you write English? | ||

| Not at all | 25 (83.00) | |

| Not well | 4 (13.00) | |

| Well | 1 (3.00) | |

| Very well | 0 (0.00) | |

Our inclusion criteria required Hmong older adults to be 50 and above. However, age was complicated for the Hmong older adults. From our video and interview data, we learned that when we recruited them, they reported their age as documented for government purposes, but when they participated in the survey, some reported their cultural age, which was marked by events. For example, there was a participant, who told us that “on paper” she is 52, but her actual age, she believes, is 47.

Table 3.

Demographic of Helpers (N=30)

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 27 (90.00) |

| Male | 3 (10.00) |

| Education | |

| Never attended school | 3 (10.00) |

| Grade 1 through 8 | 0 (0.00) |

| Grade 9 through 11 | 1 (3.30) |

| Grade 12 or General Educational Development (GED) | 9 (30.00) |

| College 1 to 3 Years | 14 (46.67) |

| College 4 Years or More | 3 (10.00) |

| Relationship to Elder | |

| Daughter | 15 (55.55) |

| Son | 3 (11.11) |

| Daughter-in-law | 3 (11.11) |

| Grand-daughter | 2 (7. 41) |

| Step-daughter | 1 (3.70) |

| Outreach coordinator | 3 (11.11) |

| Missing | 3 (10.00) |

Data Collection

After follow-up telephone calls, the researcher scheduled appointments to conduct the interview. Participants chose the location—either the community center or their home. The researcher first provided general instructions, answered questions, and obtained audiotaped oral consent in participants’ preferred language (Hmong or English). The oral consent included permission for videotaping and interviewing.

Next, the researcher provided the link to the webpage of the survey and demonstrated the use of the screen display, accessibility features, and navigation options. The survey data were collected on a laptop brought to the data collection site by the researcher. Before the dyads began, a small digital camcorder was placed at the center of the laptop in front of the dyads to capture facial expressions and interactions during completion of the ACASI-H survey. The entire process was recorded using the digital camcorder. The purpose of the video recordings was to explore communication between the dyads and observe how the technology was used.

Setting

The ACASI-H survey was completed in as natural a setting as possible. Therefore, the Hmong older adults and helpers were instructed to complete the ACASI-H survey the way they would have at home and without a researcher present. The dyads were instructed to proceed in whatever way they chose, answer only questions they would answer in a natural setting, and skip any questions they preferred not to answer. A speakerphone instead of headphones was used to deliver the prerecorded oral Hmong translation, allowing the researcher to capture on video whether and how often the dyad used the pre-recorded translation.

Content of ACASI-H survey

Twenty six-items were included in the ACASI-H: 12 items were the Acute Short Form Health Survey (SF-12; Ware, Kosinski, & Keller, 1996), one sensitive question (“Do you have a problem with urinary urgency? Yes or No?”), eight demographic questions, and five questions on use of technology. SF-12 was selected because it is generic and has been validated with other cultural groups with internal consistency reliability estimates of 0.65–0.93 (Han, Lee, Iwaya, Kataoka, & Kohzuki, 2004; Lam, Gandek, Ren, & Chan, 1998; Lewin-Epstein, Sagiv-Schifter, Shabtai, & Shmueli, 1998). The question known to contain what an older Hmong would consider sensitive (Lor, Khang, Xiong, Moua, & Lauver, 2013) was added to observe whether the sensitivity of the question might influence the response process, specifically how the older person interacted with the helper. Demographic questions for the Hmong older adults included age, gender, educational level, income, health insurance, level of literacy in both English and Hmong, and length of residence in the US. Six demographic questions were also asked of the helpers, including age, gender, relationship to the Hmong older adult, level of literacy in both English and Hmong, and length of residence in the US.

Design of ACASI-H Survey

The 26-item survey, including response categories and instructions, was first translated into Hmong, colors were added to the response categories, and a bilingual and bicultural female Hmong researcher pre-recorded an oral Hmong version of each question and response option. The survey was programmed using Qualtrics.

Translation

A team approach rather than the more commonly used back-translation was used for survey translation. A team of translators and translation reviewers made decisions by consensus about the translation quality, with continual modifications (Mohler, Dorer, Jong, & Hu, 2016). Our team included three bilingual Hmong health researchers (nurse, public health professional, and a professional interpreter). This approach is recommended by cross-cultural survey researchers over back-translation because it has provides a rich array of options for translation and a balanced critique of translation versions (Guillemin, Bombardier, & Beaton, 1993; Harkness, Pennell, & Schoua-Glusberg, 2004; Mohler et al., 2016).

Colored band development

When the translation of questions was deemed understandable and of high quality, a color-labeled band was placed above the text response items. Response categories (e.g., yes/no) were each linked to a unique color and read in Hmong to the participants to accommodate their inability to read either Hmong or English. In addition, colors were designed to enable communication between the helper and the older person. The computer screen displayed the question and color-labeled response band options above the English written response category texts. As the audio-recording of each question was played, it was accompanied by a presentation of the response categories in two forms: (a) English text and (b) a colored band above the English text. The recording included instructions for selecting the color corresponding to each response category. This combination of screen display and audio instruction allowed older Hmong participants to select a response by color, while the helper could view the response in English written text to confirm that the older adult’s intention had been achieved. This feature accommodated common differences in fluency levels between the older adult and the helper.

After the survey was programmed in Qualtrics, the researchers asked eight participants to provide feedback on comprehension, clarity of translation, and the color-labeled response categories. Some colors elicited emotional responses from the Hmong older adult participants. Lighter colors were perceived as positive and darker colors as negative. The response items were changed to be consistent with the feedback. Lighter, brighter colors (yellow, blue, green, pink) were used for positive response categories, and darker colors (black and red) were used for negative response categories (see Figure 1).

Semi-Structured debriefing interviews

Immediately following completion of the online ACASI-H survey, the researcher conducted a face-to-face debriefing interview with the dyads to explore their experiences with ACASI-H, specifically in terms of feasibility (Table 4). The older adults and the helpers took turns providing responses. The use of the planned questions was responsive to what the participants shared, to prevent repetition and enhance rapport. For example, when we asked a participant, “What was it like for you?” and the participant responded with “I could not use the computer, but I like the questions asked,” we would not ask the question “Can you use a computer?” Instead, we followed up with, “Tell me more about your experience with technology.”

Table 4.

Sample Debriefing Interview Questions

| Feasibility Category | Question Directed at | Sample Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Overall experience | Older adult & helper |

|

| Survey experience |

|

|

| Usability of technology | Older adult & helper |

|

| Older adult |

|

|

| Usability of pre-recorded oral translation | Older adult & helper |

|

| Usability of response categories labeled with colors | Older adult & helper |

|

| Practicality of including helpers | Helper |

|

Following the debriefing interview, the researcher and the dyad watched the video of the dyad completing the ACASI-H survey and discussed the interactions between the Hmong older adult and the helper. For example, the dyad was asked, “How did you decide who would complete the form?” followed by probes based on the video content. Four dyads opted not to review the videos with the researchers, and 26 dyads reviewed the videos.

All interviews and video reviews were audio-recorded. At the end of the interviews, the Hmong older adults and helpers each were given $20 and were offered a copy of the video. The 26 dyads who reviewed their videos accepted the offer to keep a video copy.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistical analyses were performed using NCSS 9.0. Video data were used to complement participants’ responses during the debriefing interviews. A team approach was used to analyze recorded interview data, which was transcribed in Hmong and then translated into English. Translations were based on meanings rather than literal translations (Harkness, Pennell, & Schoua-Glusberg, 2004). The team consisted of a translator (undergraduate honors student) and two reviewers (a Hmong nurse researcher and a professional Hmong translator), ensuring that spoken terms and expressions were both technically correct and consistently translated by the majority of the group.

The researchers read each transcript word by word and took notes to capture key concepts before meeting to compare their codes. Conventional and directed content analyses were used to analyze interview transcripts and videos (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Conventional content analysis (open-ended, non-directed coding) was used to analyze the responses related to participants’ overall experience. For example, participants were initially asked a broad, non-directive question, “Tell me what it was like for you,” to obtain a sense of the whole. The open-ended question yielded very little specific responses other than general acceptability of their experience. Nor did the respondents provide additional information in response to the specific questions. For instance, a participant commented that “the questions correspond to my health.” This response was coded as “survey content was consistent with health.” After we coded all responses to the open-ended question, we sorted the codes into categories based on the relationships and linkages among the codes, using an iterative process. The subcategories were then organized into a “General Experience” content area.

Next, directed content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005; Graneheim,& Lundman, 2004) was used to categorize responses to the more specific interview questions using predetermined categories based on the research purpose. For example, participants were asked about (a) the usability of technology, (b) the usability of the pre-recorded oral translation, (c) the usability of response categories labeled with color, and (d) the inclusion of helpers. Participants’ responses aligned well with questions. However, very little detail was offered. For example, relating to the implementation of technology, we asked participants, “Did you have any technical difficulty taking the survey (e.g., browser problem, audio problem)? Tell me about the challenges.” The responses to this were coded under the “usability of technology” category. For example, one participant responded, “Your recording, when we press play, it goes for two seconds and it stops. And then it kind of stops loading.” This statement was coded as “survey loading error” under the category “usability of technology.”

Results

There were no missing data for the 12-item survey and sensitive question, but data were missing from the older adults’ demographic items: age (13%; n=4), marital status (3%; n=1), income (40%; n=12), years of education in the US (7%; n=2), and number of years lived in the US (7%; n=6). Survey completion time ranged from 11 to 50 minutes, with a mean of 20 minutes.

The face-to-face debriefing interviews covered five major content areas concerning the ACASI-H experience. They were: (a) general experience with ACASI-H, (b) usability of technology, (c) usability of pre-recorded oral translation, (d) usability of color-labeled response categories, and (e) inclusion of helpers.

General Experience with ACASI-H

All participants reported a positive experience with the ACASI-H survey. They found the process of survey taking to be “easy,” stating that they would not change anything about it. All Hmong older adult participants reported they would take the ACASI-H survey again if it were given to them in the future.

Acceptability of ACASI-H Health Survey Questions

All older Hmong participants described the survey questions as consistent with their health experience and described the survey questions as easy to answer. One Hmong older adult stated that, “The questions were good. For us elders, it’s correct about what the questions asked.” All participants described the length of the ACASI-H survey as “just right.” One participant stated, “This [survey] is perfect. This is doable and usable. It is not too long or too short.” No Hmong older adults reported the survey questions to be sensitive or embarrassing. One said, “There is nothing that is embarrassing.”

Despite this expressed ease and acceptability, many Hmong older adults described being unfamiliar with surveys and having difficulty choosing a response from the response categories offered. One Hmong older adult stated, “Since this is my first time, I didn’t really know how to answer.” Another Hmong older adult explained that, “I have never done something like this before. So I am not able to measure myself … whether it [my stress] was a lot or a little.”

Usability of Technology

Every Hmong older adult described inability to operate the laptop or use the mouse, and all reported lacking experience and being generally uncomfortable with technology. As one Hmong older adult said, “It is too difficult. I don’t even know how to turn on the television.” Another Hmong older adult stated, “I have never touched it [the laptop] before…I don’t even know where to start.” In all instances, only the helper operated the laptop and mouse. One Hmong older adult said, “We need a child to help us use it.”

All helpers agreed that their older adults were unable to use the technology and agreed that their presence was required to complete the survey. One helper said, “I prefer to be here to help my mother because she doesn’t know how to use technology.” All helpers described the technological components of the ACASI-H survey (e.g., going to the next question) as easy to navigate.

Nonetheless, four dyads experienced technical difficulties at the start of the survey. These difficulties included not being able to advance to the next question and not being able to hear the audio translation for one question. One helper said, “There were like two or three of them [questions]…it wouldn’t load. It keeps saying, ‘Block’…”.

Usability of the Hmong Pre-Recorded Oral Translation of Survey Questions

Twenty-nine of the 30 (97%) dyads reported using the Hmong pre-recorded oral translation for all ACASI-H survey items. Only one helper translated the complete ACASI-H survey without using the pre-recorded oral translation. She read the English text and then translated each response option into Hmong for her mother, explaining that it was what she always did and what her mother preferred.

Although 29 dyads used the Hmong pre-recorded oral translation, four of the helpers described having to translate orally when the oral translation failed to load. Significantly, all four of these helpers reported discomfort translating, as they were not fluent in either Hmong or English and were uncertain about the accuracy of their translation. One helper said, “I only know what it is but don’t know how to verbally translate it out so that people will know and understand it.” Although the helpers appeared to be fluent in English, 26 (87%) Hmong helpers reported they did not read English well at all.

The 29 Hmong older adult participants (97%) and their helpers who used it all described the oral translation as clear and understandable and said it worked well. One helper stated that “…the audio recording, reading of the questions, that I think is something that is good for people who do not really know how to read text.” Ninety-seven percent of helpers reported that the pre-recorded oral translation was also helpful to them. Of the 29 Hmong older adults, 25 described the volume of the pre-recorded audio translation as good, and four described it as “not loud enough.” Of the four older adults who described the volume as not loud enough, three were in the oldest age category (>70), and one had a hearing problem.

Usability of Response Categories Labeled With Color

All Hmong older adult participants reported that the color-labeled categories were useful as substitutes for written response category options. One Hmong older adult said, “If there are the colors then it is much easier.” The majority of helpers agreed. In addition, some Hmong older adults reported that colors helped them recall the response categories better. One helper said, “…That’s a great idea because a lot of them [Hmong older adults], they cannot remember what you said, but they remember the colors … It does match up.” Another Hmong older adult said, “…for those who do not know how to read or write at all, responding based on the colors will help.” A third Hmong older adult stated, “I do like it. If there are no colors then I wouldn’t know how to answer.”

Despite the dyads’ positive perception of the usability of response categories labeled with colors, the Hmong older adults’ had two distinct initial reactions to the color-labeled response categories. Twenty-five (83%) understood the correspondence between the responses and the color labels, but five (17%) Hmong older adults initially responded to the cultural meaning of the colors rather than to the content of the corresponding response labels that were read to them.

Effective color-labeled categories

The 25 (83%) Hmong older adults who found the color-labeled categories effective reported not needing the helper to explain how to select the appropriate response categories. They understood the relationship between the colors and the content of the response categories.

Furthermore, the color-labeled categories helped the Hmong older adults and helpers who were not fluent in either Hmong or English. The helpers reported that the color-labeled categories sped up the survey process. One helper who was not fluent in Hmong stated,

I really liked it. It was all color-coded. I think that was very helpful for me as a helper too [helper laughs], especially not knowing and not being fluent [in Hmong], you know, it really helped navigate everything along.

Initially ineffective color-labeled categories

The strong, traditional meanings of colors caused initial confusion for five Hmong older adult participants (17%), who responded to the cultural meaning of the color, noting what the color meant to them rather than the content of the response labels. They required multiple reminders from their helpers about how to respond, that is, not to base their responses on preference for a color and to focus on the content of the question. In this situation, the helpers clarified the intended meaning of colored labels by re-explaining the relationship between the color and the content of the response categories. One helper explained,

We listened to the translation that you recorded and then when you say the colors, she keeps looking at the colors to see what she wants to choose. So I told her “Listen, it is not about picking the color. You have to listen to the color and what each response is.”

The five Hmong older adults did not understand this distinction until the third question in the survey. Once the Hmong older adult participants understood the instructions, they found the color-labeled response categories to be helpful in answering the questions.

Inclusion of Helpers

Acceptability

All Hmong older adults and helpers confirmed that having helpers present during the survey process was acceptable and necessary. Both the Hmong older adults and the helpers reported a strong preference for the helpers to assist the Hmong older adults complete this or any future surveys. All Hmong older adults reported that they were comfortable having their helpers assist them. All helpers acknowledged their older adults’ literacy and technology limitations and that their older adults’ lack of familiarity with surveys made it necessary to have a helper present.

Practicality

The Hmong older adults reported several benefits to having their helpers participate in the ACASI-H response process, including assisting in navigation (e.g., laptop, mouse, online ACASI-H survey), identifying when the older adult did not understand the questions, clarifying questions, explaining how to respond to the colored labels, and helping them select the most accurate response for each question when they encountered a challenge (e.g., not sure how to communicate their true state using the response categories available to them).

Navigating technology

All helpers described navigating the web-based survey, including playing the audio and clicking the response, because the Hmong older adults were unfamiliar with technology. One helper described her assistance as follows:

I helped her click and use the mouse and to click to go to the next questions, and click the audio for her. I usually let her listen to the audio first… Then she will tell me, “oh, this is more of me.” Then I will click the color option for her.

Providing clarification and explaining how to respond

Both the Hmong older adults and helpers shared that the helpers played an important role in helping the older adults understand the survey items and color-labeled response categories when the older adults appeared to be confused. For example, helpers clarified the meaning of color-labeled response categories for the Hmong older adults: “If there is a question, even after listening to the translation, and you still don’t understand, they [helper] can explain it to you.”

The helpers also used their personal knowledge of the older adults as a basis to compare the older adults’ answers and to help them to decide on a response. One helper stated:

I tried to explain it to her to make sure that she understands and knows what it is before answering. If she doesn’t answer correctly and I think that it doesn’t really match her then I tried to re-explained it to her so they she can understand better.

Helping select the most accurate response

Five Hmong older adults who had difficulty selecting a response reported that the helpers were needed to classify their responses when they had a difficult time choosing the appropriate response item. One helper stated,

Sometimes I made the decision for my mom like “this answer fits you best,” and then I will tell her to pick that one. When two colors are close to one another then I say “maybe one of these two colors is accurate to you,” and then she will choose between the two.

Discussion

In this study we assessed the feasibility of using ACASI-H for data collection with Hmong older adults who are not literate in Hmong or English. Building on the strong family ties and the multigenerational, linguistically diverse households that are common in collectivist cultures could be an effective and acceptable approach to collecting health-related data from this difficult-to-reach population. This may be particularly useful when the helpers and older adults differ in language proficiency and comfort with technology. The expectation in collectivist cultures that family members are highly interdependent and where the group is the unit of survival creates an opportunity for researchers to reach this population (Chen & West, 2008).

This study provides evidence that using ACASI-H with Hmong older adult/helper dyads is feasible and may also have relevance for other non-literate populations from oral, collectivist cultures. Asians and Hispanics comprise the largest collectivist cultures in the US (Population Reference Bureau, 2013), with many continuing to live in multigenerational households characterized by a mix of language proficiency.

The ACASI-H functioned without many problems on the laptop computer carried house to house and community center to community center for data collection. Some Hmong older adults and helpers reported loading problems for the oral translation. Having a back-up option, in this case a helper who translated, was helpful. In addition, because the Hmong older adults were unfamiliar with computers, the helpers provided the support they needed to make the ACASI-H survey process effortless and manageable.

That five Hmong older adults had difficulty at first responding to the colors representing response options cannot be readily explained and raises important questions for future survey development. We found that colors have cultural meanings. More studies are needed to understand how color influences survey responses. Despite initially struggling with distinguishing between the meaning of the colors and the content of the response categories, when debriefed, all participants preferred to have the color-labeled response categories in the survey. They described the color-labeled response categories as helpful in communicating their answers to the helpers. A similar result was found in studies of a previous version of the colored ACASI (C-ACASI), with colored stickers on specific keyboard keys (Bhatnagar et al., 2013; Kauffman & Kauffman, 2011). Given that it took some older Hmong adults over 4 minutes to respond correctly to the first three questions in the survey, future research could focus on developing practice questions for Hmong older adults to answer prior to answering the actual questions. This would allow them to become familiar with and understand the content of the survey and the colored label responses.

We added a new component to survey research by including a family helper during the completion of ACASI and found that family helpers improved the feasibility and acceptability of ACASI-H for the older Hmong participants. In particular, the helpers played an important role in ensuring good quality data by providing clarification when the older adults did not understand the questions. The helpers explained how to respond to the color coding, clarifying the meaning of the colored labels for response categories, and helping the older adults select the most accurate response for each question when they encountered difficulty. Although the helpers appeared to improve the data collection and quality, future researchers could examine how helpers might contribute to bias and random error or whether their interpretation actually increases quality.

It took the dyads an average of 20 minutes to complete the 26 items in the survey. This increased length of time in comparison to typical surveys was understandable because the ACASI-H survey included a helper to aid communication in a complex cultural interaction where there may be cultural or conceptual issues that may be related to language and cultural barriers. In addition, Hmong older adults said they were not familiar with answering questions in a survey with color-labeled response categories. Therefore, it may require more working memory to understand the questions and consequently take a longer time for them to provide a response. We found no studies of the time required for other racial and ethnic groups or older adults to complete the SF-12 survey. Future researchers could pursue this question.

There were several limitations of this study. The ACASI-H survey was not compared to other forms of data collection (e.g., ACASI-H survey vs. a paper survey), and so we cannot conclude that the ACASI-H survey offered the best method for collecting health data for NL populations, although it appears to be a method worth exploring in more detail in future research. In addition, we did not standardize the interview process or control what the family helpers could or could not do. As a result, measurement error in this procedure could be different from that in a more standardized procedure. However, the natural setting provided important evidence of events when a survey is completed by people in their homes. Additionally, the ACASI-H survey was only tested with one LEP and NL older adult group—Hmong older adults. Future studies are needed to test how well this mode of data collection works with other groups with LEP, such as Spanish speakers or speakers of other Asian languages. Because the ACASI-H survey accommodates the collectivist Hmong culture by including a family helper, lack of participant privacy may be a limitation, but we do not think privacy is of concern to this group because family members are individuals in whom Hmong older adults confide.

Future studies are needed to assess measurement error with this method in comparison to other administration modes and to assess whether the helper could introduce bias. It is possible that having the video camera in front of the dyads could have influenced their behavior and/or responses, but many of the dyads seemed unaware of the presence of the camera during the process, some wondering aloud whether they were being recorded yet.

Conclusion

This is the first test of the feasibility and acceptability of the ACASI-H survey for use with Hmong older adults with limited English. The Hmong dyads (older adult and helper) found ACASI to be easy to use and were comfortable with it. Although further refinement of administration procedure may be needed, there were no missing data for the ACASI-H survey items, and the ACASI-H survey was judged feasible and acceptable for collecting personal health data from this older Hmong sample. This data collection method can be useful to increase survey research participation for other non-English speaking populations.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), Grant # F31NR015966 and the University of Wisconsin-Madison, School of Nursing’s Eckburg Research Award. This study was also partially supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR000427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors would like to thank Nora Cate Schaeffer for guiding the author in this study and for helpful feedback, committee members Roger Brown, Elizabeth A Jacobs, Tracy Schroepfer, Barbara King, and Audrey Tluczek for feedback, Nathan Jones from the UW-Madison Survey Center for helping with the color-coding labels, and the participants.

Contributor Information

Maichou Lor, University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Nursing, 701 Highland Ave., Madison, WI 53705.

Barbara J. Bowers, University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Nursing, Madison, WI

References

- Bhatnagar T, Brown J, Saravanamurthy PS, Kumar RM, Detels R. Color-coded audio computer-assisted self-Interviews (C-ACASI) for poorly educated men and women in a semi-rural area of South India: “Good, Scary and Thrilling. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(6):2260–2268. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0414-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casado BL, Leung P. Migratory grief and depression among elderly Chinese American immigrants. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2002;36:5–26. doi: 10.1300/J083v36n01_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC health disparities and inequalities report (CHDIR) 2013 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/CHDIReport.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Promoting culturally sensitivity: A practice guide for tuberculosis programs that provide services to Hmong persons from Laos. 2008 Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/guidestoolkits/ethnographicguides/hmongtbbooklet508_final.pdf.

- Chen C, Lee SY, Stevenson HW. Response style and cross-cultural comparisons of rating scales among East Asian and North American students. Psychological Science. 1995;6:170–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1995.tb00327.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, West S. Measuring individualism and collectivism: The importance of considering differential components, reference groups, and measurement invariance. Journal of Research in Personality. 2008;42:259–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley PC, Rogers SM, Turner CF, Al-Tayyib AA, Willis G, Ganapathi L. Using touch screen audio-CASI to obtain data on sensitive topics. Computers in Human Behavior. 2001;17:285–293. doi: 10.1016/S0747-5632(01)00005-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy J. Writing from these roots: Literacy in a Hmong-American community. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Estes LJ, Lloyd LE, Teti M, Raja S, Bowleg L, Allgood KL, Glick N. Perceptions of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) among women in an HIV-positive prevention program. PLOS ONE. 2010;5(2):1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frayne DSM, Burns RB, Hardt EJ, Rosen AK, Moskowitz MA. The exclusion of non-English-speaking persons from research. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1996;11:39–43. doi: 10.1007/BF02603484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayet-Ageron A, Agoritsas T, Schiesari L, Kolly V, Perneger TV. Barriers to participation in a patient satisfaction survey: Who are we missing? PLOS ONE. 2011;6(10):1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: Literature review and proposed guidelines. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1993;46:1417–1432. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurak DT, Kritz MM. Elderly Asian and Hispanic foreign- and native-born living arrangements: Accounting for differences. Research on Aging. 2010;32:567–594. doi: 10.1177/0164027510377160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han CW, Lee EJ, Iwaya T, Kataoka H, Kohzuki M. Development of the Korean version of short-form 36-item health survey: Health related QOL of healthy elderly people and elderly patients in Korea. The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2004;203(3):189–194. doi: 10.1620/tjem.203.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness J, Pennell B-E, Schoua-Glusberg A. Survey questionnaire translation and assessment. In: Presser S, Rothgeb JM, Couper MP, Lessler JT, Elizabethrtin Jeanrtin, Singer E, editors. Methods for testing and evaluating survey questionnaires. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2004. pp. 453–473. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarlais DCD, Paone D, Milliken J, Turner CF, Miller H, Gribble J, … Friedman SR. Audio-computer interviewing to measure risk behaviour for HIV among injecting drug users: A quasi-randomised trial. The Lancet. 1999;353:1657–1661. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman RM, Kauffman RD. Color-coded audio computer-assisted self-interview for low-literacy populations. Epidemiology. 2011;22:132–133. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181fefc27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam CLK, Gandek B, Ren XS, Chan MS. Tests of scaling assumptions and construct validity of the Chinese (HK) version of the SF-36 health survey. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998;51:1139–1147. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00105-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin-Epstein N, Sagiv-Schifter T, Shabtai EL, Shmueli A. Validation of the 36-item short-form health survey (Hebrew version) in the adult population of Israel. Medical Care. 1998;36:1361–1370. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199809000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link MW, Mokdad AH, Stackhouse HF, Flowers NT. Race, ethnicity, and linguistic isolation as determinants of participation in public health surveillance surveys. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2006;3(1):1–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lor M, Bowers B. Evaluating teaching techniques in the Hmong breast and cervical cancer health awareness project. Journal of Cancer Education. 2014;29:358–365. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0615-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnis AM, Muchini A, Shiboski S, Mwale M, Morrison C, Chipato T, Padian NS. Audio computer-assisted self-interviewing in reproductive health research: Reliability assessment among women in Harare, Zimbabwe. Contraception. 2007;75:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler P, Dorer B, de Jong J, Hu M. Translation: Overview. 2016:1–145. Retrieved from http://ccsg.isr.umich.edu/images/PDFs/CCSG_Translation_Chapters.pdf.

- National Asian Pacific Center on Aging. National Asian Pacific Center on Aging Annual Report 2012–2013. 2014 Retrieved from http://napca.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/2013-NAPCA_Annual_Report.pdf.

- Population Reference Bureau. Elderly immigrants in the United States. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.prb.org/About/ProgramsProjects/Aging/TodaysResearchAging.aspx.

- Reichmann WM, Losina E, GRS, Arbelaez C, Safren SA, Katz JN, … Walensky RP. Does modality of survey administration impact data quality: Audio computer assisted self interview (ACASI) versus self-administered pen and paper? PLOS ONE. 2010;5(1):1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C. Language use in the United States: 2011. American Community Survey Report; 2013. p. 16. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/acs-22.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Thao YJ. The Mong oral tradition: Cultural memory in the absence of written language. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 50th Anniversary of International Literacy Day: Literacy rates are on the rise but millions remain illiterate. UIS Fact Sheet No. 38. 2016:1–10. Retrieved from http://www.uis.unesco.org/literacy/Documents/fs38-literacy-en.pdf.

- United States Census Bureau. Census Bureau reports at least 350 languages spoken in U.S. homes. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2015/cb15-185.html.

- Villarroel MA, Turner CF, Eggleston E, Al-Tayyib A, Rogers SM, Roman AM, … Gordek H. Same-gender sex in the United States: Impact of T-Acasi on prevalence estimates. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2006;70:166–196. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfj023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whatley M, Batalova J. Limited English proficient population of the United States. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/limited-english-proficient-population-united-states.

- Wilmoth JM. Living arrangements among older immigrants in the United States. The Gerontologist. 2001;41:228–238. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Reducing health inequities through action on the social determinants of health. 2009 Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/A62/A62_R14-en.pdf.

- Yeo G, Gallager-Thompson D. Ethnicity and the dementias. 2. New York, NY: Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]