Abstract

Aims

To determine the patient-level factors associated with headache neuroimaging in outpatient practice.

Methods

Using data from the 2007–2010 National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys (NAMCS), we estimated headache neuroimaging utilization (cross sectional). Multivariable logistic regression was used to explore associations between patient-level factors and neuroimaging utilization. A Markov model with Monte Carlo simulation was used to estimate neuroimaging utilization over time at the individual patient-level.

Results

Migraine diagnoses (OR=0.6, 95% CI 0.4–0.9) and chronic headaches (routine, chronic OR=0.3, 95% CI 0.2–0.6; flare up, chronic OR=0.5, 95% CI 0.3–0.96) were associated with lower utilization, but even in these populations neuroimaging was ordered frequently. Red flags for intracranial pathology did not increase use of neuroimaging studies (OR=1.4, 95% CI 0.95–2.2). Neurologist visits (OR=1.7, 95% CI 0.99–2.9) and first visits to a practice (OR=3.2, 95% CI 1.4–7.4) were associated with increased imaging. A patient with new migraine headaches has a 39% (95% CI 24–54%) chance of receiving a neuroimaging study after 5 years and a patient with a flare up of chronic headaches has a 51% (32%–68%) chance.

Conclusions

Neuroimaging is routinely ordered in outpatient headache patients including populations where guidelines specifically recommend against their use (migraines, chronic headaches, no red flags).

Keywords: Headaches, migraines, diagnostic testing, healthcare efficiencies

Introduction

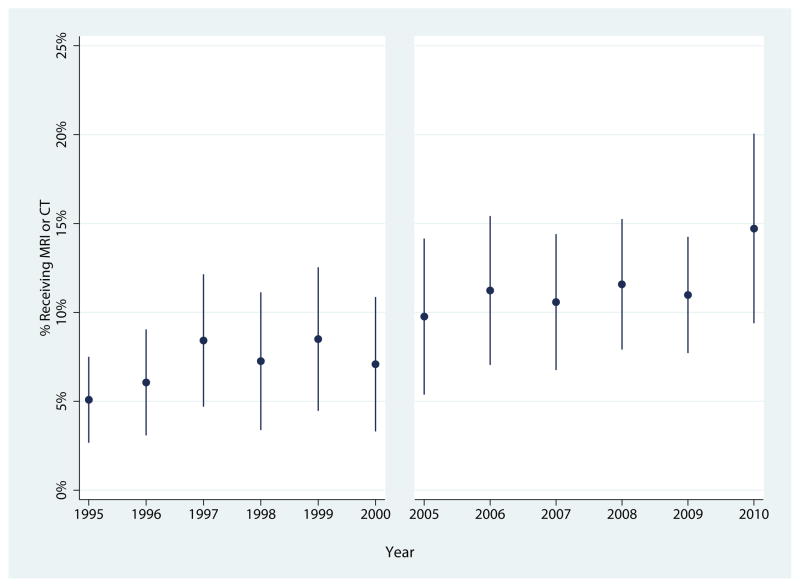

Headaches have a lifetime prevalence greater than 90%.(1) This nearly universal condition results in 13 million outpatient visits annually in the United States (ref). Headache neuroimaging is ordered in 12.4% of these visits resulting in approximately $1 billion in annual outpatient expenditures in the United States.(2) Neuroimaging is commonly ordered despite the fact that the yield of significant abnormalities in patients with migraines and chronic headaches is comparable to that seen in healthy research volunteers.(3–6) As a result, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) (migraines), European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS) (migraines), and American Academy of Radiology (ACR) (chronic uncomplicated headaches) have all released guidelines recommending against routine neuroimaging.(7–10) Furthermore, the Choosing Wisely campaign, an initiative to stimulate dialog about potentially unnecessary tests, has specifically identified neuroimaging in headache patients as a target (www.choosingwisely.org). Therefore, interventions to curb headache neuroimaging utilization have the potential to dramatically reduce healthcare expenditures and additional downsides including patient inconvenience, radiation exposure related to CT scans, and the occurrence of false positive results.

While the need to reduce headache neuroimaging is clear, little is known about the factors associated with their use, which may have implications for future health care efficiency interventions. Therefore, we aimed to identify patient demographic and clinical predictors of headache neuroimaging. We also investigated neuroimaging utilization in populations where guidelines specifically recommend against use (migraines and chronic headaches with no red flags) to determine the magnitude of guideline discordant care. We then used simulation analysis to determine the per-patient probability of headache neuroimaging over 5 years in two common clinical scenarios, a new diagnosis of migraines and a flare up of chronic headaches.

Methods

Dataset

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) is a nationally representative survey that uses a three-stage sampling design (geographic regions, physician practices stratified within specialties, and patient visits within practices) to characterize outpatient, office-based care. For this study, we analyzed all headache visits for patients over 18 years of age in NAMCS from 2007–2010. Headache visits were identified using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Single-level Clinical Classification System (CCS) (ICD-9CM codes 339.xx, 784.0x, and 346.xx) with the addition of tension headaches, 307.81. For the migraine subset of visits, ICD-9-CM codes 346.xx were used.(11)

Defining Headache Visits and Neuroimaging Appropriateness

We used a series of increasingly-specific definitions of “headache visits” in order to estimate whether headache imaging was concordant with guidelines. First, we analyzed all visits with a physician-assigned ICD-9 based headache diagnosis in any of the three diagnostic positions for the visit. Next, to increase specificity, we analyzed only visits with a principal headache diagnosis. To further increase specificity and begin to estimate guideline concordance, we then focused on all visits with a migraine ICD-9 diagnosis. For the subset of visits with a primary migraine diagnosis, we then further increased specificity by selecting the visits where there was concordance between the patient’s reason for visit and the physician’s ICD-9 diagnosis by using NAMCS headache reason for visit code, 12100. As NAMCS allows patients to report three separate reasons for visits, we investigated visits where headache was the primary reason for visit. This approach allowed us to identify neuroimaging utilization using both a maximally sensitive definition of headache visits (all visits with any headache diagnosis), as well as a maximally specific definition (visits with a primary migraine diagnosis where the patient’s primary reason for visit was also headache).

Multiple studies have identified potential “red flags” for intracranial pathology that establish the circumstances under which neuroimaging should be considered for headache patients.(7, 8, 12–14) Specifically, “red flags” were considered to be any of the following: any non-headache neurologic symptom as a reason for the visit, pregnancy or suspected pregnancy (pregnancy reason for visit or ordering a pregnancy test), fever (measured at the visit or as a reason for visit), AIDS/HIV (ICD-9 diagnoses 042.xx, V08, V0179, 759.71, or an HIV-related reason for visit),), trigeminal neuralgia (ICD-9 350.1x or 053.12), epilepsy (ICD-9 345.xx), cancer (as identified as a NAMCS comorbidity), age over 50 with a new headache, uncontrolled hypertension (BP > 180/105) and cluster headache or trigeminal autonomic cephalgia diagnosis (ICD-9 339.0x, 339.1x).

Identification of Neuroimaging

CT and MRI utilization are directly abstracted from the NAMCS survey instrument.

Analysis

We characterized the study population using descriptive statistics after applying survey weights using patient and visit characteristics as reported on the NAMCS survey instrument. We used logistic regression (Bernoulli distribution) to predict probability of receiving any neuroimaging study in the sub-population of headache visits for a series of predictor variables: age, sex, race/ethnicity, year, insurance type, whether the patient had a headache reason for visit, whether headache was the principal diagnosis, migraine diagnoses (any migraine vs. migraine with aura), the presence of any “red flag”, the number of physician visits in the last year, provider type, whether the patient has been seen before in the practice, whether the visit was for a new or chronic problem (routine or flare up), and patient comorbidities. Of note, chronic headache was defined as those patients with a headache ICD-9 diagnosis for whom the major reason for visit was identified as a chronic problem (onset greater than 3 months ago). Based on this model, average marginal effects were used to estimate the probability of receiving neuroimaging for two patient populations where guidelines specifically recommend against their use. Specifically we estimated neuroimaging utilization in the following scenarios: Scenario 1, a patient presents to a primary care physician with a primary complaint of new migraine headaches (major reason for visit was listed as new problem) without red flags; Scenario 2, a patient presents to a primary care physician with a primary complaint of a flare up of chronic headaches (major reason for visit was listed as flare up of chronic problem) without red flags.

Monte Carlo Simulation

The policy and clinical significance of receiving a neuroimaging study at a given visit is limited because it does not account for the fact that patients usually have multiple visits over time. Consequently, we developed a simulation model to translate the per-visit probability of receiving neuroimaging into the per-patient probability of receiving neuroimaging on different time scales. We used the two clinical scenarios described above and simulated neuroimaging use over 5 years of follow up. These scenarios were translated into a simple Markov model (Figure 1). The probability and distribution of receiving neuroimaging at the initial visit and at a return visit was derived from our model predicting the probability of receiving neuroimaging. The probability per year of a return visit was derived from a claims database using a flat distribution between the group with the lowest (0.54 visits/year) and highest (3.2 visits/year) frequency of headache visits.(15) A Monte Carlo process was used to estimate the probability of a patient receiving a neuroimaging study over 5 years over 10,000 random draws with replacement from the probability distributions.

Figure 1.

A Monte Carlo simulation of neuroimaging utilization for a patient presenting to their primary care physician with a new complaint of migraine headaches followed routinely for 5 years.

Results

Population

Detailed demographics of this population are presented in Table 1. Most of the population was female (78.5%) and less than 65 years of age (88.1%). Visits were to the following providers: primary care physicians (54.8%), neurologists (20%), other specialists (13%), and non-primary care generalists (12.2%). Thirty-six percent of visits were classified as a new problem, and 83.7% of patients had been seen by the same practice previously. Between 2007–2010, headache diagnoses accounted for 51.1 million visits, with migraine diagnoses comprising about half (25.4 million). In two-thirds (16.1 million) of the migraine visits, the migraine diagnosis was listed as the primary diagnosis. Of these 16.1 million migraine visits, approximately half (7.7 million) listed headaches as a reason for visit with the majority having headache as the primary reason for visit (91%). Red flags were identified in 22.9% of all headache visits and 15.3% of migraine visits.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical variables in patients with an ICD-9 diagnosis of headache

| Demographics | # Visits in millions (95% CI) | % Total (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–40 | 20.2 (16.6 – 23.8) | 39.5% (36.2% – 42.9%) |

| 41–65 | 24.8 (20.4 – 29.3) | 48.6% (45.0% – 52.2%) |

| 66+ | 6.1 (4.7 – 7.4) | 11.9% (09.8% – 14.4%) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 40.0 (33.0 – 46.0) | 78.1% (75.4% – 80.6%) |

| Male | 11.0 (9.2 – 13.0) | 21.9% (19.4% – 24.6%) |

| Race Ethnicity | ||

| White | 41.0 (34.0 – 48.0) | 80.2% (76.4% – 83.5%) |

| African American | 5.7 (4.2 – 7.3) | 11.2% (8.8% – 14.2%) |

| Hispanic | 2.4 (1.5 – 3.2) | 4.6% (3.2% – 6.6%) |

| Other | 2.0 (1.3 – 2.7) | 4.0% (2.9% – 5.6%) |

| Insurance | ||

| Private | 32.0 (26.0 – 38.0) | 62.2% (58.0% – 66.2%) |

| Medicare | 5.7 (4.5 – 7.0) | 11.3% (9.2% – 13.7%) |

| Medicaid | 6.7 (5.0 – 8.4) | 13.1% (10.6% – 16.1%) |

| Worker’s Comp | 0.7 (0.3 – 1.1) | 1.4% (0.8% – 2.4%) |

| Self Pay | 3.1 (2.3 – 4.0) | 6.1% (4.6% – 8.0%) |

| No Charge | 0.2 (0.0 – 0.4) | 0.3% (0.1% – 1.1%) |

| Other | 2.9 (1.9 – 3.9) | 5.6% (4.1% – 7.7%) |

| Comorbidities/Conditions | ||

| Arthritis | 6.2 (4.4 – 8.0) | 12.2% (9.9% – 15.0%) |

| Asthma | 3.6 (2.4 – 4.8) | 7.0% (5.4% – 9.0%) |

| Cancer | 1.4 (0.9 – 2.0) | 2.8% (1.8% – 4.3%) |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 1.2 (0.7 – 1.7) | 2.3% (1.6% – 3.4%) |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 0.1 (0.0 – 0.3) | 0.3% (0.1% – 0.8%) |

| Chronic Renal Failure | 0.2 (0.0 – 0.4) | 0.4% (0.2% – 0.8%) |

| COPD | 0.9 (0.4 – 1.4) | 1.7% (1.0% – 2.9%) |

| Depression | 10.0 (7.5 – 13.0) | 19.8% (16.9% – 23.1%) |

| Diabetes | 2.9 (1.9 – 3.9) | 5.6% (4.2% – 7.5%) |

| HIV | 0.1 (0.0 – 0.3) | 0.3% (0.1% – 1.0%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 6.8 (5.1 – 8.5) | 13.3% (11.0% – 16.0%) |

| Hypertension | 11.0 (8.8 – 13.0) | 21.3% (18.7% – 24.1%) |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 0.7 (0.3 – 1.1) | 1.3% (0.7% – 2.4%) |

| Obesity | 3.9 (2.9 – 4.9) | 7.7% (6.2% – 9.6%) |

| Osteoporosis | 1.0 (0.5 – 1.4) | 1.9% (1.2% – 3.1%) |

| Pregnancy | 0.2 (0.0 – 0.3) | 0.3% (0.1% – 1.0%) |

| Visit Characteristics | ||

| Seen by this practice before | 43.0 (36.0 – 49.0) | 83.7% (80.9% – 86.2%) |

| Year | ||

| 2007 | 2.3 (1.6 – 3.0) | 24.9% (21.2% – 28.9%) |

| 2008 | 11.0 (8.5 – 14.0) | 22.2% (18.4% – 26.6%) |

| 2009 | 16.0 (11.0 – 20.0) | 31.2% (25.8% – 37.3%) |

| 2010 | 11.0 (9.2 – 13.0) | 21.7% (18.5% – 25.2%) |

| Visits in the past year | ||

| 0 | 2.3 (1.6 – 3.0) | 4.5% (3.3% – 6.2%) |

| 1–2 | 16.0 (14.0 – 19.0) | 32.0% (29.2% – 35.0%) |

| 3–5 | 15.0 (11.0 – 18.0) | 28.4% (24.7% – 32.4%) |

| 6+ | 6.3 (4.9 – 7.6) | 12.3% (10.2% – 14.7%) |

| Unknown | 12.0 (9.2 – 14.0) | 22.8% (20.1% – 25.7%) |

| Chronicity | ||

| New Problem | 18.0 (16.0 – 21.0) | 36.0% (31.7% – 40.6%) |

| Chronic Problem, routine | 19.0 (16.0 – 22.0) | 37.3% (34.0% – 40.7%) |

| Chronic Problem, flare up | 8.5 (5.7 – 11.0) | 16.7% (13.3% – 20.7%) |

| Other | 5.1 (3.7 – 6.5) | 10.0% (8.0% – 12.3%) |

| Visit Provider | ||

| PCP | 28.0 (23.0 – 33.0) | 54.8% (50.7% – 58.8%) |

| Non-PCP Generalist | 6.3 (4.1 – 8.5) | 12.4% (9.5% – 15.9%) |

| Neurologist | 10.0 (8.2 – 12.0) | 20.0% (16.9% – 23.6%) |

| Other Specialist | 6.6 (5.0 – 8.1) | 12.9% (10.5% – 15.6%) |

COPD= chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, HIV= human immunodeficiency virus, PCP= primary care physician

Neuroimaging Utilization

The combined MRI/CT utilization was 12.4% of visits during patient visits for any headache diagnosis and 9.8% in those with a migraine diagnosis (Table 2). Neuroimaging utilization was 15.9% in visits with headache as the primary diagnosis and 11.7% in visits with migraine as a primary diagnosis. Utilization was higher for patients with a primary diagnosis of migraine and either headache as one of the reasons for visit (14.7%) or headache as the primary reason for visit (15.9%). After removing patients with red flags, the MRI/CT utilization decreased to 10.2% in those with any headache diagnosis and 8.3% in those with a migraine diagnosis.

Table 2.

Neuroimaging utilization using different definitions of a headache visit

| Total Visits # in millions (95% CI) | MRI % of Visits (95% CI) | CT % of Visits (95% CI) | MRI or CT % of Visits (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With and without red flags | ||||

| All Headaches a | 51.1 (43.2 – 58.9) | 7.6% (6.1% – 9.4%) | 5.1% (3.7% – 6.9%) | 12.4% (10.5% – 14.7%) |

| All Migraines b | 25.4 (19.6 – 31.2) | 6.0% (4.4% – 8.2%) | 3.8% (2.1% – 6.8%) | 9.8% (7.4% – 12.9%) |

| Primary Headaches c | 29.2 (23.8 – 34.6) | 10.1% (7.9% – 12.9%) | 6.2% (4.2% – 9.0%) | 15.9% (13.1% – 19.1%) |

| Primary Migraines d | 16.1 (11.6 – 20.6) | 7.2% (4.9% – 10.5%) | 4.5% (2.2% – 9.1%) | 11.7% (8.4% – 16.0%) |

| Primary Migraines headache RFV e | 7.68 (4.78 – 10.60) | 8.0% (4.8% – 13.0%) | 6.7% (3.5% – 12.6%) | 14.7% (10.0% – 21.1%) |

| Primary Migraines primary headache RFV f | 6.98 (4.17 – 9.80) | 8.6% (5.2% – 14.1%) | 7.3% (3.7% – 13.8%) | 15.9% (10.7% – 22.9%) |

| Without red flags | ||||

| All Headaches a | 39.4 (32.7 – 46.0) | 5.6% (4.4% – 7.1%) | 4.6% (3.2% – 6.8%) | 10.2% (8.3% – 12.5%) |

| All Migraines b | 21.5 (16.0 – 27.1) | 4.8% (3.4% – 6.8%) | 3.5% (1.7% – 7.1%) | 8.3% (6.0% – 11.4%) |

| Primary Headaches c | 23.2 (18.4 – 28.0) | 7.7% (5.9% – 10.1%) | 5.5% (3.4% – 8.7%) | 13.2% (10.5% – 16.4%) |

| Primary Migraines d | 14.1 (9.7 – 18.5) | 6.2% (4.1% – 9.4%) | 4.4% (1.9% – 9.7%) | 10.6% (7.4% – 15.0%) |

| Primary Migraines headache RFV e | 6.7 (3.9 – 9.5) | 7.5% (4.3% – 12.6%) | 6.1% (2.8% – 12.6%) | 13.5% (8.8% – 20.3%) |

| Primary Migraines primary headache RFV f | 6.1 (3.3 – 8.8) | 8.1% (4.6% – 13.7%) | 6.5% (2.9% – 13.7%) | 14.6% (9.4% – 22.0%) |

ICD-9CM codes of 339.xx, 784.0x, 346.xx, and 307.81 in any position.

ICD-9-CM codes 346.xx in any position

ICD-9CM codes of 339.xx, 784.0x, 346.xx, and 307.81 in the primary position.

ICD-9-CM codes 346.xx in the primary position

ICD-9-CM codes 346.xx in the primary position with headache RFV code 12100 in any position

ICD-9-CM codes 346.xx in the primary position with headache RFV code 12100 in the primary position

Multivariable logistic regression model

The c-statistic of the model was 0.66. A migraine diagnosis was associated with a significant decrease in neuroimaging utilization (OR=0.6, 95% CI 0.4–0.9), whereas headache as the primary diagnosis was associated with increased utilization (OR=2.2, 95% CI 1.3–3.6) (Table 3). Migraine with aura was not significantly associated with neuroimaging utilization. Red flags (OR=1.4 95% CI 0.95–2.2) and headache as a reason for visit (OR= 1.2, 95% CI 0.8–1.9) were not significantly associated with neuroimaging. If the reason for the visit was a chronic problem, neuroimaging utilization was decreased compared to a new problem (routine, chronic OR=0.3, 95% CI 0.2–0.6; flare up, chronic OR=0.5, 95% CI 0.3–0.95). First visits to a practice (OR=3.2, 95% CI 1.4–7.4), were significantly associated with increased neuroimaging utilization. Visits to neurologists (OR=1.7 95% CI 0.99–2.9) and a diabetes diagnosis (OR=2.0, 95% CI 0.99–4.2) were also associated with increased neuroimaging, with both approaching statistical significance.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression exploring the associations between patient demographic and clinical factors and headache neuroimaging utilization

| Odd ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (reference: 18–40) | ||

| 41–65 | 0.9 | 0.6–1.5 |

| 66+ | 0.9 | 0.4–1.9 |

| Gender (reference: female) | 0.9 | 0.6–1.4 |

| Race/Ethnicity (reference: white) | ||

| African American | 1.1 | 0.6–2.0 |

| Hispanic | 0.6 | 0.3–1.2 |

| Other | 0.7 | 0.2–2.3 |

| Headache Reason For Visit code | 1.2 | 0.8–1.9 |

| Primary Headache ICD-9 diagnosis | 2.2* | 1.3–3.6 |

| Migraine ICD-9 code | 0.6* | 0.4–0.9 |

| Red flags | 1.4 | 0.95–2.2 |

| Number of past visits (reference: none) | ||

| 1–2 | 0.4 | 0.2–1.1 |

| 3–5 | 0.5 | 0.2–1.3 |

| 6+ | 0.4 | 0.1–1.2 |

| Unknown | 0.4 | 0.1–1.2 |

| Provider type (reference: PCP) | ||

| Generalist, non PCP | 0.5 | 0.3–1.05 |

| Neurology | 1.8 | 0.99–2.9 |

| Other Specialist | 0.6 | 0.3–1.2 |

| Year of visit (reference: 2007) | ||

| 2008 | 1.1 | 0.6–1.9 |

| 2009 | 1.2 | 0.7–2.3 |

| 2010 | 1.5 | 0.7–3.2 |

| Not seen before in this practice | 3.2* | 1.4–7.4 |

| Major reason for visit (reference: new problem) | ||

| Chronic problem, routine | 0.3* | 0.2–0.6 |

| Chronic problem, flare-up | 0.5* | 0.3–0.96 |

| Other/unknown | 0.1* | 0.04–0.4 |

PCP=primary care provider

p<0.05# Additional model covariates were insurance status and comorbidities listed in Table 1.

Using this model, we estimated neuroimaging utilization under two clinical scenarios where guidelines specifically recommend against neuroimaging use. Scenario 1, for a patient presenting to their primary care physician with a primary complaint of new migraine headaches without red flags, the predicted probability of receiving neuroimaging was 14.3% (95% CI 7.4%–21.2%) at an initial visit and 5.4% (95% 2.8%–8.0%) at follow-up visits. Scenario 2, for a patient presenting to their primary care physician with a primary complaint of a flare up of chronic headaches without red flags, the predicted probability of receiving neuroimaging was 13.3% (95% CI 5.3%–21.3 %) at an initial visit and 9.0% (95% CI 4.8%–13.1%) at follow-up visits.

Monte Carlo Simulation

In scenario 1 (new migraine headaches), 20% (95% CI 11%–31%) of patients were predicted to receive a neuroimaging study at 1 year, 25% (15%–37%) at 2 years, 30% (18%–43%) at 3 years, 34% (21%–48%) at 4 years, and 39% (24%–54%) at 5 years. In scenario 2 (flare up of chronic headaches), 23% (95% CI 12%–35%) of patients were predicted to receive a neuroimaging study at 1 year, 31% (18%–45%) at 2 years, 38% (23%–54%) at 3 years, 45% (28%–61%) at 4 years, and 51% (32%–68%) at 5 years.

Discussion

In the United States, headache neuroimaging utilization is common, costly, and rising over the last two decades.(2, 16) We demonstrate that 39% of patients presenting with new migraines and over half of patients with chronic migraines will receive neuroimaging over a 5-year period emphasizing that current practice is to order these tests routinely. This is particularly concerning because these are the clinical scenarios in which current guidelines specifically recommend against their use. As a result, efforts to reduce neuroimaging in this population have the potential to improve guideline-concordant care and also substantially reduce health care costs, patient inconvenience, radiation exposure, and the occurrence of false positive results.

Current headache practice guidelines suggest that three factors should lead to fewer headache neuroimaging studies: chronic headaches, a migraine diagnosis, and absence of red flags.(7–10) We found that physicians are less likely to order neuroimaging studies in those with chronic headaches and migraines. However, neuroimaging utilization remains substantial even in these populations. Specifically, neuroimaging is performed in 14.3% of visits with a primary diagnosis of migraine as a new problem and 5.4% of subsequent visits. Similarly, neuroimaging is obtained in 13.3% of visits for patients with a primary complaint of a flare up of chronic headaches and 9.0% of subsequent visits. Surprisingly, red flags for intracranial pathology were not associated with neuroimaging. This result suggests that physicians may be ordering these tests based on variables beyond those that may increase the yield of these studies. Possibilities include patient requests for testing, patient reassurance, a desire to avoid malpractice liability, and self-referral incentives for physicians that own imaging equipment.(17) Of note, the red flag definition used in this study was designed to maximize sensitivity at the cost of specificity; therefore, some of the patients with red flags in this study likely did not have a true red flag. Consequently, we would not conclude that the low imaging utilization in the red flag study population reflects imaging underutilization in the real world red flag population. The virtue of a red flag definition with high sensitivity is that it increases the strength of inferences in the population that was not marked as having a red flag. As a result, we can more strongly conclude that the considerable neuroimaging utilization observed was not due to red flags.

Besides a primary ICD-9 diagnosis of headache, visits to a neurologist and first time visits to a practice were significantly associated with neuroimaging utilization. The fact that neurologist visits resulted in higher utilization may be due to several factors, including the tendency of specialists to order more tests, see sicker patients, perform more complete and detailed clinical histories and examinations that uncover red flags, and patient expectations for testing may be even higher when seeing a specialist.(18) However, the fact that neurologists are associated with higher utilization suggests that referrals to specialists are unlikely the answer to curbing neuroimaging utilization in this population. In contrast, the higher utilization in first visits to a practice indicates that enhancing continuity of care may be one way to limit testing. Even after adjusting for all model variables, a first visit to a practice was associated with a more than 3-fold increase in the probability of ordering a neuroimaging study. Similar findings of continuity of care resulting in lower utilization of health care services have been demonstrated previously.(19, 20) This may be explained by a provider tendency to order neuroimaging at a first encounter or a patient tendency to seek out a new provider until a neuroimaging study is ordered. In essence, limiting referrals to specialists and better continuity of care may reduce unnecessary neuroimaging tests, although future studies evaluating these potential interventions are needed as many other factors likely influence inappropriate neuroimaging utilization.

Limitations of this study include the lack of potentially relevant clinical information such as worsening of headache with exertion, Valsalva, or vomiting, or abnormal physical examination findings.(13) On the other hand, we were able to use the ICD-9 and NAMCS reason for visit codes to evaluate those with non-headache neurologic symptoms, pregnancy, fever, HIV, giant cell arteritis, trigeminal neuralgia, cluster headaches, epilepsy, and cancer. Similarly, the accuracy of the headache diagnosis cannot be ascertained with this data as the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) classification is not provided. This is an important limitation as the specific headache classification may influence the utilization of neuroimaging. Moreover, we were unable to use the ICHD definition of chronic headaches. The chronicity of headaches was determined by the chronicity of the major reason for visit (new problem with onset less than 3 months ago, routine chronic problem, flare up of a chronic problem), more detailed clinical information was not available. Misspecification of either simulation model structure or parameters may have lead to inaccurate mean estimates; however, we allowed for a wide degree of parameter variation making it unlikely that that actual effects fall outside the specified confidence intervals. Another limitation is that NAMCS is an observational study that relies on physicians to fill out surveys. However, previous studies have indicated that the NAMCS method has a high degree of sensitivity, specificity, and concordance with regards to diagnostic testing when compared with direct observation of outpatient visits.(21)

The routine use of neuroimaging, even in common clinical scenarios where guidelines recommend against their use, highlights the need for interventions to curb utilization. Enhancing continuity of care is one potential way to decrease guideline discordant testing. Future studies are needed to investigate other patient and physician reasons for use and potential barriers to waste reduction efforts.

Clinical or Public Health Relevance Bullet Points.

Neuroimaging is routinely ordered in patients with a headache diagnosis, even in those clinical scenarios where guidelines specifically recommend against their use (migraines, chronic headaches, no red flags)

After 5 years, a patient with new migraines has a 40% chance of receiving neuroimaging

First visits to a physician are associated with higher utilization of neuroimaging; therefore, enhancing continuity of care is one possible intervention to curb utilization

Acknowledgments

Authorship contributions: Brian Callaghan was involved in the study design, planning and interpretation of the statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript. Kevin Kerber contributed to interpretation of the statistical analysis and critical revisions of the manuscript. Rob Pace was involved in the design and critical revisions of the manuscript. Lesli Skolarus contributed to interpretation of the statistical analysis and critical review of the manuscript. Wade Cooper contributed to interpretation of the statistical analysis and critical review of the manuscript. James Burke contributed to the study design, planning and interpretation of the statistical analysis, and to critical revisions of the manuscript.

James Burke had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

Funding/support: Drs. Callaghan is supported by the Katherine Rayner Program, the Taubman Medical Institute, and NIH K23 NS079417. Dr. Kerber is supported by NIH/NCRR #K23 RR024009, AHRQ #R18 HS017690, and 1R01DC012760. Dr. Skolarus is supported by NIH/NINDS K23NS073685 and R21-NS-084081. Dr. Burke is supported by NINDS K08 NS082597.

References

- 1.Rasmussen BK, Jensen R, Schroll M, Olesen J. Epidemiology of headache in a general population--a prevalence study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44(11):1147–57. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90147-2. Epub 1991/01/01. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callaghan BC, Kerber KA, Pace RJ, Skolarus LE, Burke JF. Headaches and Neuroimaging: High Utilization and Costs Despite Guidelines. JAMA internal medicine. 2014 Mar 17; doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke CE, Edwards J, Nicholl DJ, Sivaguru A. Imaging results in a consecutive series of 530 new patients in the Birmingham Headache Service. J Neurol. 2010 Aug;257(8):1274–8. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5506-7. Epub 2010/03/04. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris Z, Whiteley WN, Longstreth WT, Jr, Weber F, Lee YC, Tsushima Y, et al. Incidental findings on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b3016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3016. Epub 2009/08/19. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sempere AP, Porta-Etessam J, Medrano V, Garcia-Morales I, Concepcion L, Ramos A, et al. Neuroimaging in the evaluation of patients with non-acute headache. Cephalalgia. 2005 Jan;25(1):30–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00798.x. Epub 2004/12/21. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang HZ, Simonson TM, Greco WR, Yuh WT. Brain MR imaging in the evaluation of chronic headache in patients without other neurologic symptoms. Acad Radiol. 2001 May;8(5):405–8. doi: 10.1016/S1076-6332(03)80548-2. Epub 2001/05/10. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandrini G, Friberg L, Coppola G, Janig W, Jensen R, Kruit M, et al. Neurophysiological tests and neuroimaging procedures in non-acute headache (2nd edition) Eur J Neurol. 2011 Mar;18(3):373–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03212.x. Epub 2010/09/28. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandrini G, Friberg L, Janig W, Jensen R, Russell D, Sanchez del Rio M, et al. Neurophysiological tests and neuroimaging procedures in non-acute headache: guidelines and recommendations. Eur J Neurol. 2004 Apr;11(4):217–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2003.00785.x. Epub 2004/04/06. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silberstein SD. Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000 Sep 26;55(6):754–62. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.6.754. Epub 2000/09/20. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strain JD, Strife JL, Kushner DC, Babcock DS, Cohen HL, Gelfand MJ, et al. Headache. American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria. Radiology. 2000 Jun;215( Suppl):855–60. Epub 2000/10/19. eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lafata JE, Tunceli O, Cerghet M, Sharma KP, Lipton RB. The use of migraine preventive medications among patients with and without migraine headaches. Cephalalgia. 2010 Jan;30(1):97–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01909.x. Epub 2009/06/06. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Luca GC, Bartleson JD. When and how to investigate the patient with headache. Semin Neurol. 2010 Apr;30(2):131–44. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249221. Epub 2010/03/31. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Detsky ME, McDonald DR, Baerlocher MO, Tomlinson GA, McCrory DC, Booth CM. Does this patient with headache have a migraine or need neuroimaging? JAMA. 2006 Sep 13;296(10):1274–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.10.1274. Epub 2006/09/14. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MS, Lamont AC, Alias NA, Win MN. Red flags in patients presenting with headache: clinical indications for neuroimaging. Br J Radiol. 2003 Aug;76(908):532–5. doi: 10.1259/bjr/89012738. Epub 2003/08/02. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasse LA, Ritchey PN, Smith R. Predicting the number of headache visits by type of patient seen in family practice. Headache. 2002 Sep;42(8):738–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02175.x. Epub 2002/10/23. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burke JF, Skolarus LE, Callaghan BC, Kerber KA. Choosing Wisely: highest-cost tests in outpatient neurology. Ann Neurol. 2013 May;73(5):679–83. doi: 10.1002/ana.23865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao VM, Levin DC. The overuse of diagnostic imaging and the Choosing Wisely initiative. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Oct 16;157(8):574–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-8-201210160-00535. Epub 2012/08/29. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callaghan BC, Kerber K, Smith AL, Fendrick AM, Feldman EL. The Evaluation of Distal Symmetric Polyneuropathy: A Physician Survey of Clinical Practice. Arch Neurol. 2011 Nov 14;69(3):339–45. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.1735. Epub 2011/11/16. Eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson LH, Flottemesch TJ, Fontaine P, Solberg LI, Asche SE. Patient medical group continuity and healthcare utilization. Am J Manag Care. 2012 Aug;18(8):450–7. Epub 2012/08/30. eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Maeseneer JM, De Prins L, Gosset C, Heyerick J. Provider continuity in family medicine: does it make a difference for total health care costs? Ann Fam Med. 2003 Sep-Oct;1(3):144–8. doi: 10.1370/afm.75. Epub 2004/03/27. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilchrist VJ, Stange KC, Flocke SA, McCord G, Bourguet CC. A comparison of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) measurement approach with direct observation of outpatient visits. Medical care. 2004 Mar;42(3):276–80. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114916.95639.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]