Abstract

Cedecea neteri M006 is a rare bacterium typically found as an environmental isolate from the tropical rainforest Sungai Tua waterfall (Gombak, Selangor, Malaysia). It is a Gram-reaction-negative, facultative anaerobic, bacillus. Here, we explore the features of Cedecea neteri M006, together with its genome sequence and annotation. The genome comprised 4,965,436 bp with 4447 protein-coding genes and 103 RNA genes.

Keywords: Cedecea, Gram-negative, Facultative anaerobic, Genome

Introduction

The Cedecea genus is an extremely rare member of the Enterobacteriaceae family [1]. The name Cedecea was proposed in 1980 for a new genus formerly designated as CDC Enteric Group 15 [1, 2]. Cedecea is characterized by positive lipase activity, resistance to colistin and cephalothin, and the inability to hydrolyze gelatin or DNA [3–5]. Discovery was from human sources where its natural environmental habitat remains unknown, Cedecea constitutes a rare pathogen of rising importance [6]. To date, only a few species of Cedecea have been identified: C. davisae, C. lapagei and C. neteri. All three species exhibit different behaviors in the human body. C. davisae has been reported to be associated with scrotal abscess [7] and, most recently, to cause bacteraemia in patients with sigmoid colon cancer [8]. On the other hand, C. lapagei has mostly been reported to be involved in pneumonia cases [5, 9]. C. neteri is associated with bacteremia in heart disease patients [4] and patients with systemic lupus erythematosus [10].

Strain M006 is a strain of Cedecea neteri and is an aquatic isolate from the Sungai Tua Waterfall, a Malaysian tropical rainforest waterfall (N 03 19.91′ E 101 42.15′). In this study, we present an overview of the classification and features of C. neteri M006 as well as its genome sequence and annotation. There are a few C. neteri aquatic isolates deposited in GenBank and C. neteri strain M006 was one of the few isolates discovered from a waterfall which its genome feature has not been reported. Hence, here we firstly reported the genome information of C. neteri M006 isolated from a waterfall environment.

Organisms Information

Classification and features

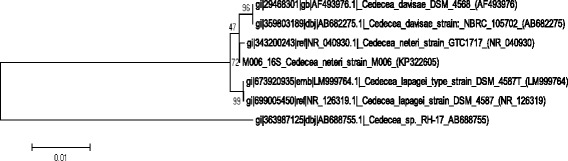

Strain M006 was categorized as a member of the genus Cedecea by 16S rRNA phylogeny and phenotypic characteristics (Table 1). The EzTaxon database [11] was used as the preliminary 16S rRNA gene sequence-based identification. Strain M006 was most closely related to C. neteri GTC 1717T (GenBank accession = AB086230) with a sequence similarity of 99.78%. Subsequent phylogenetic analysis was performed comparing the 16S rRNA gene sequences of strain M006 and related species (Fig. 1). The sequences were aligned and phylogenic trees were built using neighbor-joining (NJ) and maximum-likelihood (ML) methods implemented in MEGA version 5 [12].

Table 1.

Classification and general features of Cedecea neteri M006 according to MIGS recommendations [14]

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [22] | |

| Phylum Proteobacteria | TAS [23, 24] | ||

| Class Gammaproteobacteria | TAS [25–27] | ||

| Order unknown | TAS [23] | ||

| Family Enterobacteriaceae | TAS [28–30] | ||

| Genus Cedecea | TAS [4] | ||

| Species Cedecea neteri | IDA | ||

| Strain: M006 | |||

| Gram stain | negative | TAS [4, 10] | |

| Cell shape | bacillus | TAS [4, 10] | |

| Motility | motile | TAS [4] | |

| Sporulation | Non-spore forming | NAS | |

| Temperature range | 4-28 °C | IDA | |

| Optimum temperature | 28 °C | IDA | |

| pH range; Optimum | e.g., 5.0-8.0; 7 | IDA | |

| Carbon source | D-sorbitol, Sucrose, D-xylose, malonate | TAS [4] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | waterfall | IDA |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | unknown | IDA |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Facultative anaerobic | TAS [4, 10] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free-living | TAS [4] |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Non-pathogen | IDA |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Sungai Tua Waterfall, Malaysia | IDA |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection | 2013 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | N 03 19.91′ | IDA |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | E 101 42.15′ | IDA |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | 586 m | IDA |

Evidence codes – IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay; TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [31]

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of Cedecea neteri M006 relative to the type strains of other species within the genus of Cedecea. The strains and their corresponding GenBank accession numbers of 16S rRNA genes are indicated in parentheses. The sequences were aligned and the phylogenetic inferences were obtained using the maximum-likelihood method with MEGA version 5 [12]. The numbers at the nodes are the percentage of bootstrap values obtained by 500 replicates. Bar, 0.01 substitutions per nucleotide positions

C. neteri M006 cells are Gram-negative, bacillus in shape (0.6-0.7 × 1.3-1.9 μm), are facultatively anaerobic and are motile with 5-9 peritrichous flagella. Colonies formed on nutrient agar are 1.5 mm in diameter and non-pigmented. Scanning electron micrograph pictures of nutrient broth grown cultures showed free-floating cells and clotted cells (Fig. 2). The carbon sources utilized by C. neteri are D-sorbitol, sucrose, D-xylose and malonate. C. neteri is reported to be unable to utilize dulcitol, adoitol, L-rhamnose, erythritol, glycerol and mucate. The optimal temperature for strain M006 is 28 °C.

Fig. 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of Cedecea neteri M006. Scale bar 3.0 μm

C. neteri M006 cells are Gram-negative, bacillus in shape, survive facultative anaerobically and are motile. The colonies formed on nutrient agar are 1.5 mm in diameter and are non-pigmented. The colony is whitish in color and the appearance is round with a smooth edge. Signaling molecules, known as N-acylhomoserine lactone, are produced for communication purposes in order to regulate physiological properties. The preliminary screening of strain M006 using the bacterial biosensor Chromobacterium violaceum (CV026) showed the purple pigmentation indicative the presence of signaling molecules (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Preliminary screening for AHL. AHL screening of strain M006 with CV026. E. carotovora PNP22 and E. carotovora GS101 served as negative and positive controls respectively

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

Strain M006 was selected for the sequencing based on its phylogenetic position and the similarity of its 16S rRNA to other members of the genus Cedecea, The genome project was deposited in the Genomes On-Line Database [13] and the genome sequence was deposited in GenBank (CP009458.1). A summary of the project and the Minimum Information about a Genome Sequence (MIGS) [14] are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Genome sequencing project information

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS 31 | Finishing quality | Complete |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | PacBio |

| MIGS 29 | Sequencing platforms | PacBio |

| MIGS 31.2 | Fold coverage | 74.34× |

| MIGS 30 | Assemblers | HGAP V 2.1.1 |

| MIGS 32 | Gene calling method | IMG-ER |

| Locus Tag | LH23 | |

| Genbank ID | CP009458 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | 2014/10/22 | |

| GOLD ID | Gp0109502 | |

| BIOPROJECT | PRJNA260769 | |

| MIGS 13 | Source List Identifier | M006 |

| Project relevance | Environmental |

Growth conditions and genomic DNA preparation

Cedecea neteri M006 was cultured aerobically on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar medium at 28 °C overnight (16-18 h). Genomic DNA was extracted using the MasterPure™ DNA Purification Kit (Epicentre Inc., Madison, WI, USA). The extracted genomic DNA was examined via a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for its quality.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome of strain M006 was sequenced at the microbiome lab, High Impact Research, University Malaya, using a Pacific Biosciences single-molecule real-time (PacBio SMRT) sequencer. The sequencing was carried out using P5 chemistry on two SMRT cells with a 20-kb prepared SMRTbell library [15]. De novo assembly of 41,094 reads using the hierarchical genome assembly process in the SMRT version 2.1.1 portal resulted with one contig of 3.96 Mb in size. The sequencing average coverage is 74.34 × and this genome has a GC content of 54.41%.

Genome annotation

After genome assembly, it was analyzed using Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology server databases (version 2.0) [16], which identified 4423 predicted coding sequences with a total of 103 RNA genes. The predicted open reading frames were annotated by searching clusters of orthologous groups [17] using the Integrated Microbial Genomes Expert Review [18]. The different groups of RNAs (rRNA and tRNA) were identified by using RNAmmer 1.2 [19] and tRNAscan-SE 1.23 [20] respectively. The additional gene prediction analysis and functional annotation were performed within IMG-ER platform.

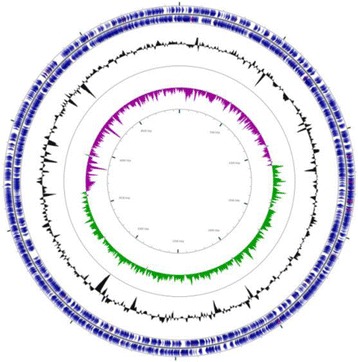

Genome properties

The genome comprised a circular chromosome with a length of 4,965,436 bp and 54.41% G + C content (Fig. 4 and Table 3). It is composed of one contig and of the 4550 predicted genes, 4447 were protein-coding genes. The properties of and the statistics for the genome are summarized in Table 3. The distribution of genes into COG functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Fig. 4.

Graphical circular map of the genome. Starting from the outermost circle and moving inwards, each ring of the circle contains information on a genome: tRNA/rRNA, genes on the reverse and forward strands, GC skew and GC ratio

Table 3.

Genome statistics

| Attribute | Value | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 4,965,436 | 100 |

| DNA coding (bp) | 4,350,834 | 87.62 |

| DNA G + C (bp) | 2,701,616 | 54.41 |

| DNA scaffolds | 1 | 100 |

| Total genes | 4550 | 100 |

| Protein coding genes | 4447 | 97.74 |

| RNA genes | 103 | 2.26 |

| rRNA genes | 22 | 0.48 |

| tRNA | 80 | 1.76 |

| Pseudo genes | 24 | 0.53 |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 3462 | 76.09 |

| Genes with function prediction | 4091 | 89.91 |

| Genes assignmed to COGs | 3611 | 79.36 |

| Genes with Pfam peptides | 4095 | 90.00 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 466 | 10.24 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1079 | 23.71 |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 | 0.00 |

Table 4.

Number of genes associated with general COG functional categories

| Code | Value | % agea | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 189 | 4.70 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 1 | 0.02 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 395 | 9.82 | Transcription |

| L | 133 | 3.31 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 0 | 0.00 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 32 | 0.80 | Cell cycle control, Cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| V | 47 | 1.17 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 181 | 4.50 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 224 | 5.57 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 117 | 2.91 | Cell motility |

| U | 105 | 2.61 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 145 | 3.60 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 231 | 5.74 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 362 | 9.00 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 412 | 10.24 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 96 | 2.39 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 158 | 3.93 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 109 | 2.71 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 266 | 6.61 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 75 | 1.86 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 409 | 10.16 | General function prediction only |

| S | 337 | 8.37 | Function unknown |

| - | 939 | 20.64 | Not in COGs |

aThe total is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome

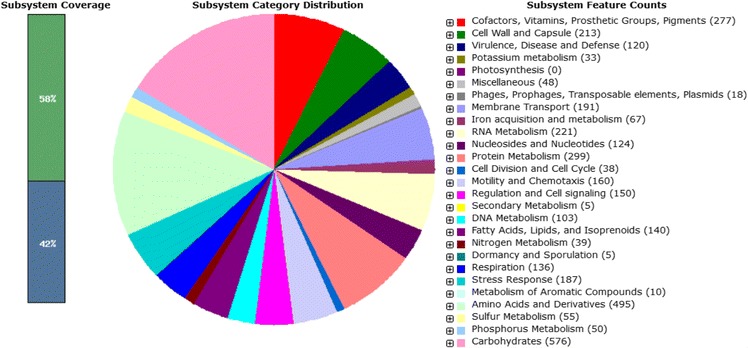

Insights from the genome sequence

RAST annotation allowed the insight of subsystem category distribution of C. neteri strain M006. This category enabled the understanding of various functional roles such as protein classes, amino acid biosynthesis and metabolic pathways. There are 552 subsystems. The most abundant subsystem feature belonged to carbohydrate metabolism (n = 576; out of a total of 3760 subsystem feature counts), followed by amino acid and derivatives (n = 495) and protein metabolism (n = 299) (Fig. 5). One of the subsystem features grouped as regulation and cell signaling was focused to allow functional genes related to quorum sensing (QS) activity to be searched. The in-silico study identified the novel LuxIR homologue of C. neteri, which was later designated as CneIR. The complete open reading frame of C. neteri strain M006 cneI and cneR homologues were found and are 462 bp and 723 bp, respectively. The complete genome sequencing allows deeper understanding of the genetic makeup that may help in identifying the linkage of pathogenicity and virulence factors with its QS properties [15].

Fig. 5.

RAST annotation of C. neteri strain M006. This annotation pipeline allows a view of the subsystem category distribution of C. neteri strain M006. Genes responsible for QS activity in this strain can be found in regulation and cell signaling subsystem (red arrow)

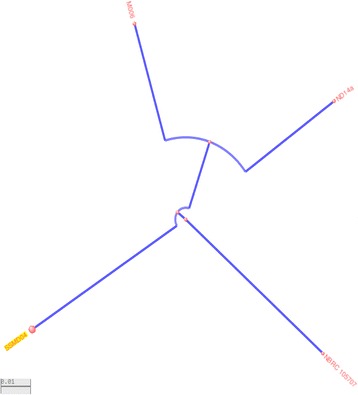

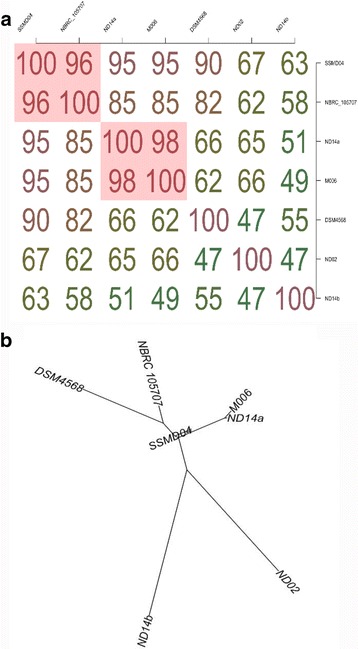

Currently, the availability of genomes of this genus is low. Only 5 complete genomes of C. neteri strains including strain M006 and a draft genome of type strain NBRC 105707 are deposited in NCBI. A matrix and dendrogram were generated based on AAI calculation that provide estimation of the average amino acid identity using best hits (one-way AAI) and reciprocal best hits (two-way AAI) between several genomic datasets of proteins [21], C. davisae type strain DSM 4568 was included in the analyses. From the analyses, we can see closer protein clustering between strain M004 and strain ND14a (Fig. 6). Some of the basic comparisons of the genomes are listed in Table 5.

Fig. 6.

AAI calculation for 6 C. neteri strains and 1 C. davisae strain. Analyses of conserved genes in the core genome computed based on AAI calculator provided (a) an AAI matrix; and (b) AAI-based phylogenetic distance tree, clustered according to distance pattern. The AAI-distance tree was clustered based on BIONJ method

Table 5.

Comparison of several strains of C. neteri

| Organism/Name | Strain | Size (Mb) | GC% | Gene | Protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. neteri | M006 | 4.97 | 54.40 | 4703 | 4531 |

| ND02 | 4.31 | 53.90 | 4053 | 3884 | |

| ND14b | 5.05 | 56.90 | 4491 | 4295 | |

| ND14a | 4.66 | 54.80 | 4426 | 4215 | |

| SSMD04 | 4.88 | 55.10 | 4622 | 4416 | |

| NBRC 105707 | 5.20 | 54.10 | 4944 | 4739 |

Conclusion

This study provides phenotypic and genomic insights into Cedecea neteri strain M006. It reports the isolation of C. neteri from an aquatic environment for the first time. This study also revealed of the QS ability of C. neteri.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the University of Malaya via High Impact Research Grants (UM.C/625/1/HIR/MOHE/CHAN/01, Grant No. A-000001-50001, UM-MOHE HIR Grant UM.C/625/1/HIR/MOHE/CHAN/14/1, no. H-50001-A000027 and GA001-2016) and University of Malaya IPPP grant No. PG090-2015B awarded to Kok-Gan Chan. The authors thank Dr. Andrew Sanderson (PhD, Nottingham) for proofreading this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AHL

N-acylhomoserine lactone

- HGAP

hierarchical genome assembly process

- LB

Luria-Bertani

- ML

Maximum-likelihood

- NJ

Neighbor-joining

- QS

Quorum sensing

- RAST

Rapid Annotation using System Technology

Authors’ contributions

WST carried out the experiment, KGC conceived the idea and supervised the whole project, all authors wrote and proofread the paper. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Grimont PAD, Grimont F, Farmer JJ, III, Asbury MA. Cedecea davisae gen. nov, sp. nov. Cedecea lapagie sp. nov, new Enterobacteriaceae from clinical specimens. Int J. Syst Bacteriol. 1981;31:317–326. doi: 10.1099/00207713-31-3-317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bae BH, Sureka SB, Ajamy JA. Enteric group 15 (Enterobacteriaceae) associated with pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol. 1981;14:774–778. doi: 10.1128/jcm.14.5.596-597.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abate G, Qureshi S, Mazumber SA. Cedecea davisae bacteremia in a neutropenic patient with acute myeloid leukemia. J Infect. 2011;63:83–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farmer JJ, III, Sheth NK, Hudzinski JA, Rose HD, Asbury MF. Bacteremia due to Cedecea neteri sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;16:775–778. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.4.775-778.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalamaga M, Karmaniolas K, Arsenis G, Pantelaki M, Daskalopoulou K, Papadavid E, Migdalis I. Cedecea lapagei bacteremia following cement-related chemical burn injury. Burns. 2008;34:1205–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalamaga M, Sotiropoulos GP, Vrioni G, Tsakris A. Cedecea: an “unknown” pathogen in the family of Enterobacteriaceae – its clinical importance, detection and identification methods. Hellenic Microbiological Society. 2014;59:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bae BH, Sureka SB. Cedecea davisae isolated from scrotal abscess. J Urol. 1983;130:148–149. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)51004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akinosoglou K, Perperis A, Siagris D, Goutou P, Spliopoulou I, Gogos CA, Marangos M. Bacteraemia due to Cedecea davisae in a patient with sigmoid colon cancer: a case report and brief review of the literature. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;74:303–306. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yetkin G, Ay S, Kayabas U, Gedik E, Gucluer N, Caliskan A. A pneumonia case caused by Cedecea lapagei. Mikrobiyol Bul. 2008;42:681–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aguilera A, Pascual J, Loza E, Lopez JL, Garcia G, Liano F, Quereda C, Ortuno J. Bacteraemia with Cedecea neteri in a patient with systemic lupus erythematous. Hospital Ramon y Cajal. 1994:179–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Kim OS, Cho YJ, Lee K, Yoon SH, Kim M, Na H, Park SC, Jeon YS, Lee JH, Yi H, Won S, Chun J. Introducing EzTaxon-e: a prokaryotic 16S rRNA gene sequence database with phylotypes that represent uncultured species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;2:716–721. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.038075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy TBK, Thomas AD, Stamatis D, Bertsch J, Isbandi M, Jansson J, Mallajosyula J, Pagani I, Lobos EA, Hyrpides NC. The Genome OnLine Database (GOLD) v.5: a metadata management system based on a four level (meta)genome project classification. Nucl Acids Res. 2015;43(D1):D1099–106. doi:10.1093/nar/gku950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:541–547. doi: 10.1038/nbt1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan KG, Tan KH, Yin WF, Tan JY. Complete genome sequence of Cedecea neteri strain SSMD04, a bacterium isolated from pickled mackerel sashimi. Genome Announcement. 2014;2:1–2. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01339-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, Meyer F, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Osterman AL, Overbeek RA, McNeil LK, Paarmann D, Paczian T, Parrello B, Pusch GD, Reich C, Stevens R, Vassieva O, Vonstein V, Wilke A, Zagnitko O. The RAST Server: Rapid annotation using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:1–15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stackerbrandt E, Ebers J. Taxonomic parameters revisited: tarnished gold standards. Microbiol Today. 2006;33:152–155. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markowitz VM, Chen IA, Palaniappan K, Ken C, Szeto E, Pillay M, Ratner A, Huang J, Tanja W, Huntemann M, Anderason I, Billis K, Varghese N, Mavromatis K, Pati A, Ivanova NN, Kyrpides IMG 4 version of the integrated microbial genomes comparative analysis system. Nucl Acids Res. 2014;42:D560–D567. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rødland EA, Stærfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucl Acids Res. 2007;35:3100–3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucl Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konstantinidis KT, Tiedje JM. Towards a genome-based taxonomy for prokaryotes. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:6258–6264. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.18.6258-6264.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Phylum XIV. Proteobacteria phyl. nov. In: Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, Garrity GM, editors. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Volume 2 (The Proteobacteria) 2. New York: part B (The Gammaproteobacteria), Springer; 2005. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Validation List No. 107 List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56:1–6. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Class III. Gammaproteobacteria class. nov. In: Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, Garrity GM, editors. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Volume 2. 2. New York: Springer; 2005. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Validation of publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSEM. List no. 106. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:2235–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Williams KP, Kelly DP. Proposal for a new class within the phylum Proteobacteria, Acidithiobacillia classis nov., with the type order Acidithiobacillales, and emended description of the class Gammaproteobacteria. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:2901–2906. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.049270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved lists of bacterial names. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1980;30:225–420. doi: 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahn O. New principles for the classification of bacteria. Zentralbl Bakteriol Parasitenkd Infektionskr Hyg. 1937;96:273–286. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Judicial Commission Conservation of the family name Enterobacteriaceae, of the name of the type genus, and designation of the type species OPINION NO. 15. Int Bull Bacteriol Nomencl Taxon. 1958;8:73–74. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarvel L, Kasarskis A, Lewis S, Matese JC, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]