To the Editor

The prescribing of antipsychotic medications persists at high levels in US nursing homes (NHs) despite extensive data demonstrating marginal clinical benefits and serious adverse effects, including death.1,2 However, imprecise and outdated data have limited the understanding of the current state of antipsychotic medication prescribing in NHs.3 We analyzed recent and detailed NH prescription data to address: (1) What is the current level of antipsychotic use? (2) Does antipsychotic use in NHs display geographic variation? and (3) Which antipsychotics are most commonly prescribed?

Methods

We used September 2009 through August 2010 prescription dispensing data from a large, long-term care pharmacy (Omnicare Inc) that serves 48 states and half of all NH residents in the United States. Pharmacy claims data are complete and accurate due to the connection to reimbursement documentation. Data elements include state location, patients’ sex, age, and enrollment dates, and national drug codes for all drugs dispensed regardless of payer (eg, Medicare Part D, private insurance, and out of pocket).

Overall and state-level annual prevalence of antipsychotic use was calculated as the percentage of NH residents receiving at least 1 antipsychotic drug. We arrayed the states into distributions of lowest to highest quintiles of antipsychotic use, calculated means and 95% confidence intervals, generated a map to illustrate geographic variation, and tested for differences using a robust regression model with quintile indicators. We identified the name and type of antipsychotic (atypical or conventional) and estimated the median and interquartile range (IQR) of the number of prescriptions and duration of use calculated as days receiving therapy during the first 90 days observed. All analyses were calculated using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc) and 2-sided tests; statistical significance was set at P<.05. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Results

We identified 1 402 039 unique NH residents and a subset of residents observed continuously for at least 90 days (n=561 681 residents and n=5038 NHs). Approximately 39.4% of study NHs had more than 100 residents, 76.2% were for profit, and 59.7% had multiple owners.

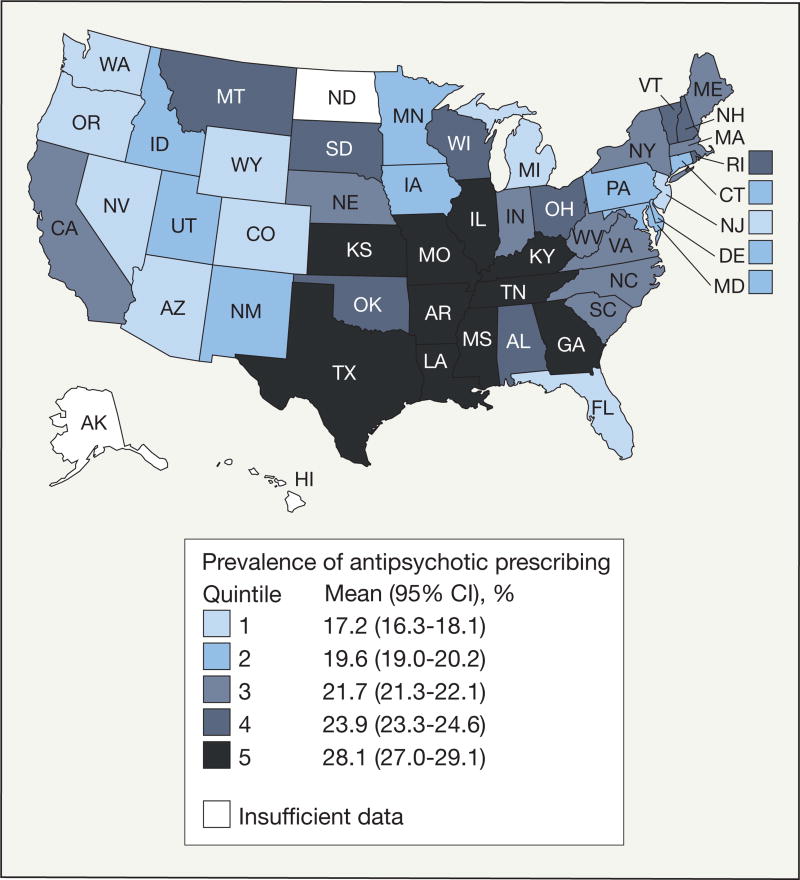

Of the overall sample of 1 402 039 NH residents, 308 449 (22.0%; 95% CI, 21.9%–22.1%) received 1 or more prescriptions of antipsychotics. Prevalence of antipsychotic drug prescribing in NHs varied significantly (quintile 1 vs quintiles 2–5, P<.001) with the highest quintile states (28.1%; 95% CI, 27.0%–29.1%) located in the central south and the lowest quintile states (17.2%; 95% CI, 16.3%–18.1%) located mostly in the west (Figure). Of 4 338 723 antipsychotic prescriptions in NHs, the majority (68.6%; 95% CI, 68.5–68.7) were for the atypical agents quetiapine fumarate, risperidone, and olanzapine (n=2 988 573) (Table). Among the 186 076 residents receiving antipsychotics and observed for 90 days, 13 956 (7.5%; 95% CI, 7.3%–7.6%) received only 1 prescription for antipsychotics while the median number was 10 (IQR, 5–14) prescriptions. The median duration of antipsychotic therapy during the 90-day observation period ranged from 30 (IQR, 8–74) days to 77 (IQR, 67–85) days.

Figure.

State-Level Prevalence of Antipsychotic Prescribing in Nursing Homes

State-level samples ranged from 767 to 104 460 residents.

Table.

Most Commonly Prescribed Antipsychotic Medications in Nursing Homes (NHs)

| Generic Drug Name | No. of Residents Prescribed Drug |

% of Total Prescriptions |

Type of Antipsychotic |

Duration of Use During 90-Day Stay in NH, Median (IQR), da |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quetiapine fumarate | 1 356 223 | 31.1 | Atypical | 72 (67–85) |

| Risperidone | 1 061 897 | 24.4 | Atypical | 70 (50–83) |

| Olanzapine | 570 453 | 13.1 | Atypical | 70 (48–83) |

| Haloperidol | 402 077 | 9.2 | Conventional | 30 (7–70) |

| Aripiprazole | 347 900 | 8.0 | Atypical | 69 (50–82) |

| Clozapine | 232 125 | 5.3 | Atypical | 77 (67–85) |

| Ziprasidone | 138 881 | 3.2 | Atypical | 66 (30–82) |

| Chlorpromazine | 65 159 | 1.5 | Conventional | 30 (8–74) |

| Fluphenazine | 54 867 | 1.3 | Conventional | 54 (26–76) |

| All othersb | 109 141 | 2.9 | Atypical and conventional | 70 (52–83) |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Calculated among 186 076 residents of NHs receiving at least 1 antipsychotic and observed for at least 90 days.

Includes paliperidone, perphenazine, thiothixene, loxapine, trifluoperazine, combination of olanzapine and fluoxetine, asenapine, lloperidone, molindone, pimozine, trilafon, loxitane, and mesoridazine.

Comment

Our finding that 22.0% of NH residents received antipsychotics in 2009–2010 is within the lower range of rates that were documented 25 years earlier before the passage of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987, which instituted regulations on the appropriate use of antipsychotics in NHs.4,5

The reasons for our findings are unclear. Geographic variation suggests the absence of an evidence-based approach to the use of these medications in NHs. The most common antipsychotics prescribed are often used for off-label indications related to dementia, and the extended durations of use raise concerns about the care of frail elders residing in NHs.

While our study included data from only 1 long-term care pharmacy, a comparison of our sample with data from NHs in the 2010 Online Survey, Certification and Reporting showed substantial overlap (61.9% vs 66.4% female, respectively; 66.4% vs 71.4% aged ≥75; and 54.5% vs 66.0% eligible for Medicaid). We were unable to assess appropriate vs inappropriate prescribing.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant R18HS019351-01. Dr Briesacher was also supported by research scientist award K01AG031836 from the National Institute on Aging.

Role of the Sponsor: The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Additional Contributions: We thank Kathy M. Mazor, EdD, Leslie R. Harrold, MD, MPH, and Celeste A. Lemay, MPH (Meyers Primary Care Institute and University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester), and Jennifer L. Donovan, PharmD, RPh, Abir O. Kanaan, PharmD (Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Worcester), for collaborating on the study. We also thank Sarah Foy and Sruthi Valluri (Meyers Primary Care Institute, Worcester, Massachusetts) for administrative assistance in preparing the manuscript. No compensation was received by any of the persons listed.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Briesacher had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Briesacher, Tjia, Gurwitz.

Acquisition of data: Briesacher.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Briesacher, Tjia, Field, Peterson, Gurwitz.

Drafting of the manuscript: Briesacher.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Briesacher, Tjia, Field, Peterson, Gurwitz.

Statistical analysis: Briesacher, Tjia, Field, Peterson.

Obtained funding: Briesacher, Tjia, Gurwitz.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Briesacher.

Study supervision: Briesacher.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Dr Briesacher reported receiving research support and consulting fees from Novartis. Dr Tjia reported serving as a consultant to Qualidigm. No other disclosures were reported.

References

- 1.Briesacher BA, Limcangco MR, Simoni-Wastila L, et al. The quality of antipsychotic drug prescribing in nursing homes. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(11):1280–1285. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.11.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maher AR, Maglione M, Bagley S, et al. Efficacy and comparative effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic medications for off-label uses in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;306(12):1359–1369. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y, Briesacher BA, Field TS, Tjia J, Lau DT, Gurwitz JH. Unexplained variation across US nursing homes in antipsychotic prescribing rates. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(1):89–95. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shorr RI, Fought RL, Ray WA. Changes in antipsychotic drug use in nursing homes during implementation of the OBRA-87 regulations. JAMA. 1994;271(5):358–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rovner BW, Edelman BA, Cox MP, Shmuely Y. The impact of antipsychotic drug regulations on psychotropic prescribing practices in nursing homes. AmJ Psychiatry. 1992;149(10):1390–1392. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.10.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]