Abstract

Depression is the most important nonmotor symptom in blepharospasm (BL). As facial expression influences emotional perception, summarized as the facial feedback hypothesis, we investigated if patients report fewer depressive symptoms if injections of botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) include the “grief muscles” of the glabellar region, compared to treatment of orbicularis oculi muscles alone. Ninety BL patients were included, half of whom had BoNT treatment including the frown lines. While treatment pattern did not predict depressive symptoms overall, subgroup analysis revealed that in male BL patients, BoNT injections into the frown lines were associated with remarkably less depressive symptoms. We hypothesize that in BL patients presenting with dystonia of the eyebrow region, BoNT therapy should include frown line application whenever justified, to optimize nonmotor effects of BoNT denervation.

Keywords: botulinum neurotoxin, blepharospasm, depression, facial feedback, frown lines, grief muscles

Introduction

In blepharospasm (BL) and other focal dystonias, depression is the most important non-motor symptom, requiring adequate attention in the overall treatment strategy. While interaction of mood and movement disorders is complex and mutual, two sources of depression are unique in facial dystonia: First, as involuntary facial movements and impaired controllability of gestures exert a strong effect on social appearance, BL patients often experience stigmatization.1 Second, facial expression influences the emotional perception of oneself (summarized as the facial feedback hypothesis2), and patients with facial dystonia including forehead or eyebrows often display a mien of sadness, grief, or frown. These negative expressions are similar to those of patients with major depression, in whom activation of corrugator and procerus muscles in the glabellar region contributes to facial features like omega melancholicum and Veraguth’s folds (Figure 1).3 Interestingly, recent controlled studies provide evidence that a single injection of botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) into the frown lines alleviates symptoms of major depression in psychiatric patients, predominantly in women.4 BoNT represents the treatment of choice for most facial dystonias and was shown to improve the quality of life with improved social functioning and mental disposition.5 Moreover, it reduces depressive symptoms in BL patients when injected into the orbicularis oculi muscle.5 Assuming a facial feedback mechanism participating in disturbances of mood in BL patients, BoNT treatment strategies including the injection of frown lines should improve depressive symptoms independently from other treatment strategies (eg, medication). The rationale for this study was to investigate if BL patients treated with BoNT report fewer depressive symptoms, when injections include the “grief muscles” of the glabellar region.

Figure 1.

Omega melancholicum and veraguth’s folds in two male patients.

Notes: (A) 73-year-old patient with major depression. (B) 65-year-old patient with blepharospasm. Dystonic movements include the frown line.

Patients and methods

In 2014, files of all BL patients of the outpatient units for movement disorders and BoNT treatment at the Department of Ophthalmology, and the Department of Neurology, were considered for the study. All files were analyzed by the same author (JRB). Patient inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) idiopathic BL, 2) treatment with BoNT in 2010, and 3) information on depressive symptoms as measured by Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI), obtained after at least one BoNT injection cycle. Patients were excluded from the study if they had 1) evidence for a nonidiopathic origin of BL, 2) disease onset before adulthood, 3) dystonia exceeding focal distribution (ie, generalized dystonia), or 4) diagnosis of affective or schizophrenic psychosis. In those patients, we analyzed treatment details retrospectively, stratifying patients into subgroups defined by BoNT treatment pattern: 1) excluding frown line application: injections of orbicularis oculi muscle only (“excl. frown line”); 2) including frown line application: injections of orbicularis oculi plus procerus, frontalis, or corrugator supercilii muscles (“incl. frown line”).

Data were analyzed using Stata (V. 13.0, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). BDI values were calculated as medians with the respective 95% CI. In subgroups, BDI values were compared using robust regression analysis, because they were not distributed normally as shown by Shapiro–Wilk test. Furthermore, Cook–Weisberg test detected heteroscedasticity in our data. Multiple regression analysis was undertaken to account for the effects of age on BDI values. A Poisson regression model was used to compare subgroups defined by BDI ≥10. P-values below 0.05 were considered significant. Also, as patients in prior depression studies were mainly female,4 the effect of gender was calculated (multiple regression model).

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Bonn (vote 156/07). All patients participating in the study gave written informed consent. Also, both patients in Figure 1 agreed to the publication of their images.

Results

Of 340 files screened, 90 patients were included (26%), 62 of which were female (68%). In all patients, BoNT injection patterns had been chosen according to the extent of dystonic facial movements, and in 45 patients (50%), BoNT treatment included frown line application. Total BDI values did not differ significantly between both treatment patterns (excl. frown line: BDI 7 [CI, 6.1–10.1]; incl. frown line: BDI 6 [CI, 6.1–9.5]; P=0.810). Also, prevalence of an at least mild disturbance of mood (BDI ≥10) was not different in both groups (excl. frown line: n=12; incl. frown line: n=16; P=0.5). Of the 28 patients with depressive symptoms identified here (31%), eight were on antidepressive medication (six with frown line injection and two without frown line injection; 9% of all patients). There were no further differences in patients’ characteristics and demographics with regard to the two treatment groups as indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study sample of 90 blepharospasm patients, with subgroups according to frown line involvement

| Item | All patients | Blepharospasm subgroups

|

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excluding frown lines | Including frown lines | |||

| Number | 90 | 45 | 45 | |

| Females | 68% | 60% | 76% | 0.11F |

| Age (years) | 67 (27–86) | 67 (27–86, 63–70) | 67 (43–83, 64–69) | 0.56M |

| Age at disease onset (years) | 60 (15–69) | 60 (15–69, 53–59) | 58 (30–68, 52–58) | 0.61M |

| Disease duration (years) | 9.5 (1–44) | 10 (1–40, 8–13) | 8 (2–44, 8–14) | 0.73M |

| Disease severity score (JRS) | 6 (3–8) | 6 (3–7, 5–6) | 6 (4–8, 5.9–6.4) | 0.36M |

| BoNT treatments (n) | 19 (1–101) | 18 (1–97, 18–33) | 19 (1–101, 21–36) | 0.44M |

| BDI score | 7 (0–31) | 7 (0–31, 6–10) | 6 (0–24, 6–10) | 0.91M |

| BDI score ≥10 (n) | 28 (31%) | 12 (27%) | 16 (36%) | 0.50F |

| Antidepressants (n) | 8 (9%) | 2 (4%) | 6 (13%) | 0.26F |

Notes: All results are given in median, range, and 95% CI, if not stated otherwise.

Fisher’s exact test;

Mann–Whitney test.

Abbreviations: BDI, Beck’s Depression Inventory; BoNT, botulinum neurotoxin; JRS, Jankovic Rating Scale.

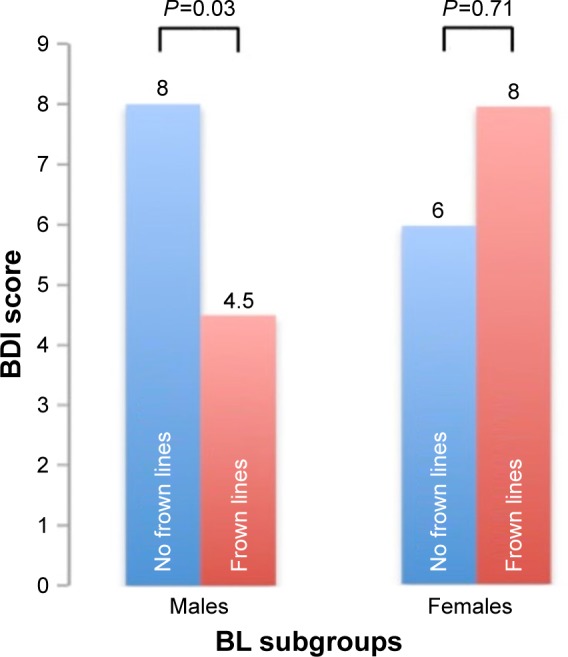

However, in subgroup analysis according to gender, male patients had significantly lower BDI values when treatment pattern included the frown lines (excl. frown lines n=18, BDI 8 [CI, 5.4–11.4]; incl. frown line: n=10, BDI 4.5 [CI, 2.4–6.6]; P=0.03; Figure 2). In patients receiving BoNT application to the frown lines, the median number of injection cycles was significantly higher in female (n=23 [CI, 23.5–41.5]), than in male patients (n=16.5 [CI, 7.6–22.2]; P=0.002). Also, female patients had longer disease duration than males (female: 11 years, range [2–44], CI, 9.34–16.43 vs males: 4 years, range [3–16], CI, 2.99–9.41, P=0.03). Considering subgroup differences in potential confounders, calculations were controlled for age, number of BoNT treatments, and disease duration. The effect of treatment pattern on male patients was stable, and even more obvious when comparing subgroups defined by BDI ≥10 (frequency of patients with BDI ≥10, excl. frown line: 1.47 [95% CI, 0.13–2.57]; incl. frown line: 0; P=0.041; not shown).

Figure 2.

BDI score in BL subgroups defined by gender and treatment pattern.

Notes: Analysis was controlled for age, number of BoNT treatments, and disease duration. Data are given as median.

Abbreviations: BDI, Beck’s Depression Inventory; BL, blepharospasm; BoNT, botulinum neurotoxin.

In women, no effect of treatment pattern on BDI values (excl. frown line: n=27, BDI 6 [CI, 5.1–10.7]; incl. frown line: n=35, BDI 8 [CI, 6.7–10.8]; P=0.71), or on prevalence of depression (BDI ≥10), became obvious.

Discussion

In this pilot study, BoNT injections into the frown lines were associated with less depressive symptoms in male BL patients. Our observations might be explained by the facial feedback hypothesis,2 which implicates a mutual influence of facial muscle activity and emotions. So far, this concept was not studied in neurological disorders, nor in BL patients, and mechanisms underlying the facial feedback hypothesis remain to be clarified. A recent research letter comparing data from three randomized placebo-controlled studies investigating the effect of BoNT on depression revealed that 1) antidepressive response to BoNT was inversely correlated with the severity of glabellar frown lines; 2) severity of frown lines was not predictive of baseline depression severity; and 3) improvement of depression after BoNT treatment was not related to a visible effect in frown line severity.6 As such, effects of BoNT on depression – in addition to improvement of vision – are feasible. Interestingly, in healthy volunteers, who imitated facial expressions of anger after peripheral denervation of frown muscles with BoNT, functional magnetic resonance imaging revealed a reduced activation of the left amygdala and associated autonomic brainstem regions.7 This impact on the interaction of facial expression and limbic activation might represent another mechanism of BoNT denervation on depressive symptoms in BL patients. Of note, there are no studies investigating isolated BoNT injections into the frown lines, without treatment of the orbicularis oculi muscle. This study design would allow more detailed analysis of the therapeutic potential of BoNT injections on depression in BL patients. However, we believe that facial feedback mechanisms of dystonic disturbance of both – frown line and orbicularis oculi muscle regions – promote depression in BL patients, and therefore, should be treated in parallel.

Remarkably, we observed no effect of BoNT frown line treatment on depressive symptoms in women with BL, in contrast to psychiatric patients with major depression.4 Besides the lower number of male patients in our study, which might restrict comparison, this observation could be attributed to the higher number of frown line treatment cycles in our female patients. At the moment, we do not know if this reflects attenuation to the effects of BoNT on facial features over a longer course of treatment, which might result in an abatement of emotional response. In major depression, improvement continued over 24 weeks, even though the cosmetic effects of BoNT wore off at 12–16 weeks.4 Eventually, men are more susceptible to effects of facial feedback than women, albeit previous studies in psychiatric patients permit no conclusion.8 Previous studies revealed gender differences in emotional perception, with men being better to recognize anger.9 Furthermore, gender-dependent differences in rating dynamic facial expressions were observed: men estimated expression of anger (not happiness) more intense, when a dynamic, not a static, stimulus was given, while women equally judged dynamic stimulus of both – anger and happiness – as more intense.9,10 As such, BoNT treatment might attenuate the dynamic nature of frowning in BL – resembling a mien of grief or anger – leading to a weaker reaction in men.

We are well aware that our study has several limitations. Interpretation of our results requires a note of caution for the overall interpretation, as the study is limited because of the small sample size and the retrospective analysis of BDI values. Also, we have no information on depressive symptoms, or therapy with antidepressants, before initiation of BoNT treatment. Nevertheless, as depression is common in BL patients, attention and assessment of mood symptoms is mandatory, regardless of prior treatment with conventional antidepressants.

Based on current evidence and our observations, we hypothesize that in BL patients presenting with dystonia of the eyebrow region, BoNT therapy should include frown line application, to optimize nonmotor effects of denervation. Furthermore, we believe that the robust effects observed in male BL patients justify to link the facial feedback mechanism, and its modulation by BoNT treatment, to facial movement disorders. However, before adjoining the facial feedback mechanism to the multiple facets of BoNT treatment in dystonia, prospective studies are required. Also, gender-specific responses to stigma and impaired controllability of gestures in dystonia have to be addressed.

Acknowledgments

The abstract of this paper was presented at the Nineteenth International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders 2015 as a poster presentation with interim findings. The poster’s abstract (poster number 1282) was published in “Poster Abstracts” in Movement Disorders, Volume 30, Issue Supplement S1, June 2015, Pages S568–S63: DOI: 10.1002/mds.26296.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Dr Janis Rebecca Bedarf has received travel grants and honoraria for scientific presentations from IPSEN Pharma Germany and MERZ Pharmaceuticals Germany and has also received financial support from the PD Fonds Deutschland gGmbH, outside the submitted work. Dr Joan Philipp Michelis reports personal fees and non-financial support from MERZ Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from IPSEN Pharma Germany, outside the submitted work. Dr Sied Kebir has nothing to disclose. Prof Dr Bettina Wabbels received travel and research grants and honoraria for scientific presentations from Allergan Germany, Desitin Germany and MERZ Pharmaceuticals Germany, outside the submitted work. Dr Sebastian Paus reports personal fees from Allergan Germany, personal fees from IPSEN Pharma Germany, personal fees from MERZ Pharmaceuticals Germany, outside the submitted work. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Rinnerthaler M, Mueller J, Weichbold V, Wenning GK, Poewe W. Social stigmatization in patients with cranial and cervical dystonia. Mov Disord. 2006;21(10):1636–1640. doi: 10.1002/mds.21049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zajonc RB. Emotion and facial efference: a theory reclaimed. Science. 1985;228(4695):15–21. doi: 10.1126/science.3883492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greden JF, Genero N, Price HL. Agitation-increased electromyogram activity in the corrugator muscle region: a possible explanation of the “omega sign”? Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(3):348–351. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.3.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Poth PE, et al. Treatment of major depressive disorder using botulinum toxin A: a 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):837–844. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ochudlo S, Bryniarski P, Opala G. Botulinum toxin improves the quality of life and reduces the intensification of depressive symptoms in patients with blepharospasm. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(8):505–508. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reichenberg JS, Hauptman AJ, Robertson HT, et al. Botulinum toxin for depression: does patient appearance matter? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(1):171–173.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hennenlotter A, Dresel C, Castrop F, Ceballos-Baumann AO, Wohlschläger AM, Haslinger B. The link between facial feedback and neural activity within central circuitries of emotion new insights from botulinum toxin-induced denervation of frown muscles. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(3):537–542. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magid M, Finzi E, Kruger TH, et al. Treating depression with botulinum toxin: a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;48(6):205–210. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1559621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biele C, Grabowska A. Sex differences in perception of emotion intensity in dynamic and static facial expressions. Exp Brain Res. 2006;171(1):1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0254-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rotter NG, Rotter GS. Sex differences in encoding and decoding of negative facial emotion. J Nonverbal Behav. 1988;12(2):139–148. [Google Scholar]