Abstract

Importance

Emphasizing sun protection behaviors among young children may minimize sun damage and foster lifelong sun protection behaviors that will reduce the likelihood of developing skin cancer, especially melanoma.

Objective

To determine whether a multicomponent sun protection program delivered in pediatric clinics during the summer could increase summertime sun protection among young children.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized controlled clinical trial with 4-week follow-up that included 300 parents or relatives (hereafter simply referred to as caregivers [mean age, 36.0 years]) who brought the child (2-6 years of age) in their care to an Advocate Medical Group clinic during the period from May 15 to August 14, 2015. Of the 300 caregiver-child pairs, 153 (51.0%) were randomly assigned to receive a read-along book, swim shirt, and weekly text-message reminders related to sun protection behaviors (intervention group) and 147 (49.0%) were randomly assigned to receive the information usually provided at a well-child visit (control group). Data analysis was performed from August 20 to 30, 2015.

Intervention

Multicomponent sun protection program composed of a read-along book, swim shirt, and weekly text-message reminders related to sun protection behaviors.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Outcomes were caregiver-reported use of sun protection by the child (seeking shade and wearing sun-protective clothing and sunscreen) using a 5-point Likert scale, duration of outdoor activities, and number of children who had sunburn or skin irritation. The biologic measurement of the skin pigment of a child's arm was performed with a spectrophotometer at baseline and 4 weeks later.

Results

Of the 300 caregiver-child pairs, the 153 children in the intervention group had significantly higher scores related to sun protection behaviors on both sunny (mean [SE], 15.748 [0.267] for the intervention group; mean [SE], 14.780 [0.282] for the control group; mean difference, 0.968) and cloudy days (mean [SE], 14.286 [0.282] for the intervention group; mean [SE], 12.850 [0.297] for the control group; mean difference, 1.436). Examination of pigmentary changes by spectrophotometry revealed that the children in the control group significantly increased their melanin levels, whereas the children in the intervention group did not have a significant change in melanin level on their protected upper arms (P < .001 for skin type 1, P = .008 for skin type 2, and P < .001 for skin types 4-6).

Conclusions and Relevance

A multicomponent intervention using text-message reminders and distribution of read-along books and swim shirts was associated with increased sun protection behaviors among young children. This was corroborated by a smaller change in skin pigment among children receiving the intervention. This implementable program can help augment anticipatory sun protection guidance in pediatric clinics and decrease children's future skin cancer risk.

The incidence of melanoma is 74 000 cases per year, and it is the second most common form of cancer among adolescents and young adults in the United States.1,2 Whether it occurs during childhood or adolescence, sun exposure increases the risk of skin cancer.3,4 Emphasizing sun protection behaviors among young children may minimize sun damage and foster lifelong sun protection behaviors that will reduce the likelihood of developing melanoma.

Sun protection is one of the anticipatory guidance topics recommended by Bright Futures, a national health promotion and prevention initiative led by the American Academy of Pediatrics (https://brightfutures.aap.org/Pages/default.aspx). Handouts that pediatric clinicians can provide to families include age-specific information about sun protection.5 An estimated 43% of US children 6 to 11 years of age experience 1 or more cases of sunburn each year,6 thus demonstrating the need for better sun protection education of caregivers. Our hypothesis is that pediatricians' seasonal age-specific sun protection recommendations would be more effective if supported by a home program that reinforced effective strategies for sun protection.

Recommended strategies for sun protection include the use of sunscreen, sun avoidance, and the use of sun-protective clothing.1 While sunscreen use and sun avoidance were the most frequently used strategies (62% and 27% of children, respectively, used these strategies), the use of sun-protective clothing, which is effective when wet, is as effective as sunscreen in reducing the number of moles, which are precursors of and the strongest risk factor for the development of melanoma, on the bodies of children.6-9 Our objective was to determine whether a multicomponent intervention that gave a read-along book and a sun-protective swim shirt to children in pediatric clinics and sent 4 weekly text-message reminders could increase summertime sun protection among young children.

Methods

Study Setting and Dates

This randomized controlled clinical trial was performed from May 15 to August 14, 2015, at 2 urban pediatric clinics with 15 participating pediatricians. The clinical locations serve populations in which 38% of adults older than 25 years of age hold bachelor's degrees or higher degrees, the median household income is approximately $69 000, and the population is 88%white, 3% African American, and 10% Hispanic or Latino.10 This study was approved by the Northwestern University institutional review board and the Advocate Health Care institutional review board (trial protocol in Supplement 1). Informed consent was obtained from all participating parents of eligible children.

Recruitment

Parents or relatives (hereafter simply referred to as caregivers [mean age, 36.0 years]) were enrolled in this study if they were at least 18 years of age, could read in either English or Spanish, brought a child between 2 and 6 years of age to a well-child visit, were able to receive text messages, and would return for a follow-up visit in 4to 6 weeks. The caregivers were recruited by on-site research assistants.

Interventions

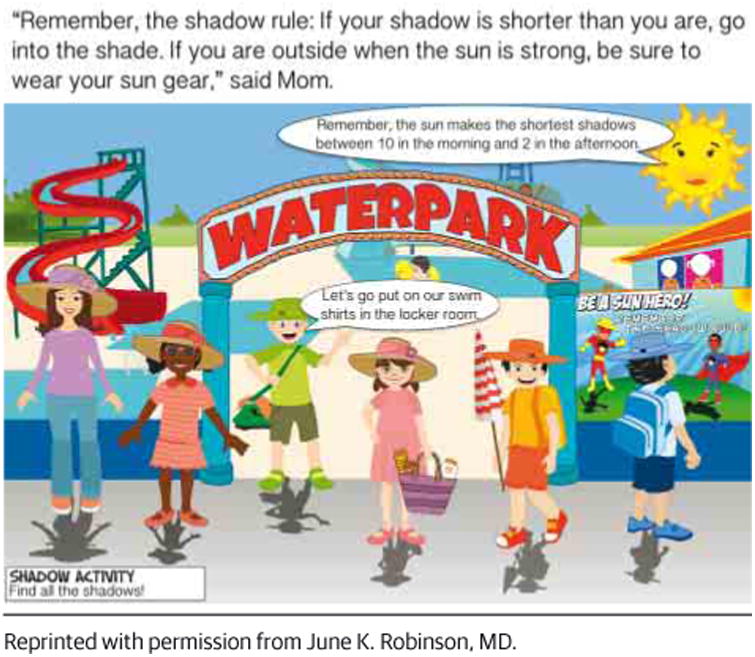

Block randomization by day to either the intervention or control group ensured that children in the control group did not see the intervention materials. Pediatricians were blinded to the randomization and did not perform verbal sun protection counseling. Some distributed age-appropriate Bright Futures handouts. After the conclusion of the visit with the pediatrician, those in the intervention group received a read-along book and a sun-protective swim shirt and made an appointment to return for a visit with the research coordinator in about 4 to 6 weeks. The 13-page read-along book emphasized sun protection behaviors with child characters representing all ethnic/ racial groups going to a water park11 (Figure 1). Between baseline and follow-up visits, 4 sun protection reminders were sent weekly via text messages. The caregivers completed an exit survey at the follow-up visit.

Figure 1. Representative Page From a Read-Along Book Demonstrating Sun Protection Behaviors.

“Remember, the shadow rule: If your shadow is shorter than you are, go into the shade. If you are outside when the sun is strong, be sure to wear your sun gear.” said Morn. Reprinted with permission from June K. Robinson, MD.

After completing an exit survey, the caregivers in the control group received all study materials (read-along book and swim shirt) at the follow-up visit. The caregivers received a $20 gift card when the baseline assessment was completed and a $50 gift card when the follow-up assessments were completed.

Data Collection

A prospective study design was used to survey caregivers at baseline and at follow-up 4 weeks later. Each eligible child's skin melanin content was assessed by spectrophotometry at base-line and follow-up (Mexameter MX18 probe; Courage + Khazaka Electronic GmbH).12

Measures

At baseline, data on the demographic characteristics and sun sensitivity of the caregiver and the child were obtained. Information on the child's skin color was obtained by showing color bars to the caregiver, who was instructed to select the bar that most closely resembled the color of the child's skin on the upper inner arm and to circle 1 of 6 numbers beside the bar (signifying skin types 1-6).13 Children with skin type 4, 5, or 6 were grouped together because they are unlikely to have either sunburn or sun irritation when in temperate climates.

At baseline and follow-up, the child's sunburn or skin irritation was assessed by the caregiver indicating how many times in the past month the child (1) “had red or painful sunburn (even a small part of his/her skin) for more than 12 hours” or (2) “had skin irritation from the sun (even a small part of his/her skin) for more than 12 hours” (Cronbach α = .94, determined by use of an internal reliability test). The caregiver reported the average number of hours the child was outside per day between 10 AM and 4 PM in the past month (α = .81) (survey in eAppendix in Supplement 2).

Data on sun protection by the child were provided by the caregiver reporting on the frequency of 5 behaviors using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “never” to “always.” These behaviors were assessed separately for warm sunny days and warm cloudy days for a total of 10 questions at baseline and follow-up. These behaviors included wearing sunscreen, a shirt with sleeves covering the shoulders, a hat with a brim, and sunglasses and staying in the shade. The 5 questions assessing sun protection behavior during sunny days were summed to create an aggregate score for sunny-day behaviors (range, 5-25; α = .63 at baseline; α = .53 at follow-up); the 5 questions assessing sun protection behavior during cloudy days were aggregated to create a score for cloudy-day behaviors (range, 5-25; α = .53 at baseline; α = .60 at follow-up).14

Another set of scales separated each of the 5 skin protection behaviors, and each scale consisted of the sum of 2 items: Likert scale scores for behavior frequency on a warm sunny day and on a warm cloudy day (range, 2-10). For example, the scores for sunscreen use on a sunny day and the scores for sunscreen use on a cloudy day were summed for an overall score of sunscreen use. All 5 scales had significant correlations between the 2 items within each scale (all P < .01) at both base- line and follow-up (for sunscreen behavior, r = 0.712 at baseline and r = 0.679 at follow-up; for shirt behavior, r = 0.830 at baseline and r = 0.815 at follow-up; for hat behavior, r = 0.801 at baseline and r = 0.813 at follow-up; for sunglasses behavior, r = 0.792 at baseline and r = 0.828 at follow-up; and for shade behavior, r = 0.770 at baseline and r = 0.792 at follow-up).

Biologic Measure

The melanin indices of the sun-exposed right dorsal forearm and the sun-protected (when wearing a short-sleeved shirt) right upper outer arm near to the shoulder were obtained with the spectrophotometer at the baseline and follow-up visits for both control and intervention groups. The area under the intensity curve along the 450- to 615- nm wavelength interval of reflected light ranges from 1 to 1000, with the lower range associated with light skin color.

Intervention-Specific Measures

The weekly text messages that elicited yes or no responses from caregivers in the intervention group were as follows: (1) Did you read the book with your child? (2) During the past week, did your child wear a hat? (3) During the past week, did your child wear the swim shirt given at the first study visit? (4) In the past week, did your child get a sunburn or skin irritation on even a small part of skin?

Statistical Analysis

Based on preliminary data showing that sun protection behaviors increased 20% after counseling, the sample size required to detect a 20% difference in using sun protection between the control and intervention groups was 300 (150 in each group), assuming an α level of less than .05 and a power of 80% or greater in a 2-tailed test. For our comparison of sun protection use on both sunny and cloudy days, it was determined that we would be able to detect effect sizes that correspond to small η2 values (ie, proportion of explained variance), in the range of 2% (or smaller). The sample sizes were expected to yield a power of greater than 90%.

The primary outcome measure was sun protection use on both sunny days and cloudy days. Two 2 (condition) by 2 (time) mixed-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed, one for the sunny-day behaviors scale and one for the cloudy-day behaviors scale.

Next, the intervention effects on specific skin protection behaviors were assessed (sunscreen, shirt, hat, sunglasses, and shade behaviors). For these analyses, five 2 (condition) by 2 (time) mixed-measures ANOVAs were performed. Lastly, to determine whether individual behaviors were affected by the intervention, ten 2 (condition) by 2 (time) mixed-measures ANOVAs were performed, one for each behavior on sunny days and one for each behavior on cloudy days. When omnibus significant effects were observed, post hoc pairwise comparisons using the Tukey test were used to compare mean values across the groups as recommended by Jaccard.15

Additional outcomes for participating children include change in melanin index, number of children who had sunburn or skin irritation from sun, and duration of outdoor activities. Differences between the intervention and control groups were analyzed using mixed-measures ANOVA followed by the Tukey test, the 2-tailed t test, and the χ2 test, respectively.

Results

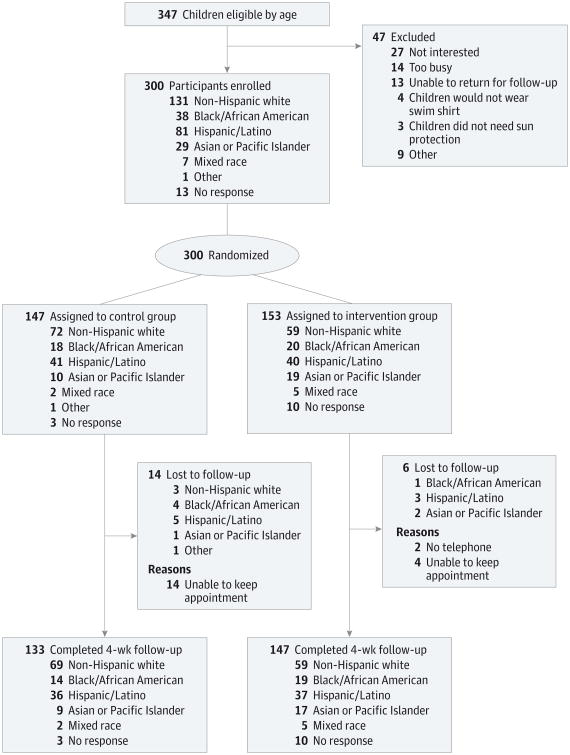

Of 347 eligible caregiver-child pairs, 300 (86.5%) participated in our study. Of the 300 caregiver-child pairs, 153 (51.0%) were randomly assigned to receive a read-along book, swim shirt, and weekly text-message reminders related to sun protection behaviors (intervention group), and 147 (49.0%) were randomly assigned to receive the information usually provided at a well-child visit (control group) (Figure 2). There were significant differences between the groups in the type of care-giver-child relationship and in the level of education of the mothers and fathers. Independent-groups t tests comparing groups on parental history of skin cancer (t = -2.915; P = .65), parental skin sensitivity (t = -1.935; P = .05), and child skin sensitivity (t = -0.518; P = .61) showed no significant differences (Table 1).

Figure 2. CONSORT Diagram.

Tabl 1. Characteristics of Caregivers and Children.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | χ2 Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n = 153) | Control (n = 147) | ||

| Caregiver | |||

| Age, y | |||

| 16-30 | 41 (26.8) | 36 (24.5) | 6.710 |

| 31-40 | 100 (65.4) | 89 (60.5) | |

| 41-50 | 12 (7.8) | 17 (11.6) | |

| >50 | 5 (3.3) | 5 (3.4) | |

| Relationship to child | |||

| Mother | 140 (91.5) | 132 (89.8) | 8.309a,b |

| Father | 13 (8.5) | 8 (5.4) | |

| Relative | 0 (0.0) | 7 (4.8) | |

| Mother's highest level of education | |||

| Middle school 7th-9th grades | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.1) | 11.653a,b |

| Some high school | 7 (4.6) | 1 (0.7) | |

| High school graduate | 19 (12.4) | 18 (12.2) | |

| Some post–high school education | 27 (17.6) | 33 (22.4) | |

| College graduate or advanced degree | 100 (65.4) | 89 (60.5) | |

| Father's highest level of education | |||

| Middle school 7th-9th grades | 2 (1.3) | 8 (5.4) | 18.71a,c |

| Some high school | 14 (9.2) | 5 (3.4) | |

| High school graduate | 26 (17.0) | 43 (29.3) | |

| Some post–high school education | 20 (13.1) | 28 (19.0) | |

| College graduate or advanced degree | 86 (56.2) | 58 (39.5) | |

| Did not respond | 5 (3.3) | 5 (3.4) | |

| Annual household income, $ | |||

| 10000-19 999 | 13 (8.5) | 20 (13.6) | 3.727 |

| 20000-34 999 | 29 (19.0) | 25 (17.0) | |

| 35000-50 999 | 19 (12.4) | 25 (17.0) | |

| 51000-100 000 | 39 (25.5) | 34 (23.1) | |

| >100000 | 32 (20.9) | 27 (18.4) | |

| Did not respond | 21 (13.7) | 16 (10.9) | |

| Hispanic (all Hispanic white) | |||

| Yes | 40 (26.1) | 41 (27.9) | 2.968 |

| No | 110 (71.9) | 106 (72.1) | |

| Did not respond | 3 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Race | |||

| White (including Hispanic) | 99 (64.7) | 113 (76.9) | 6.105 |

| Black | 20 (13.1) | 18 (12.2) | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 19 (12.4) | 10 (6.8) | |

| Mixed race | 5 (3.3) | 2 (1.4) | |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Did not respond | 10 (6.5) | 3 (2.0) | |

| Child | |||

| Age, y | |||

| 2-3 | 54 (35.3) | 50 (34.0) | 0.236 |

| >3-4 | 26 (17.0) | 23 (15.6) | |

| >4-5 | 27 (17.6) | 28 (19.0) | |

| >5-6 | 46 (30.1) | 46 (31.3) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 69 (45.1) | 75 (51.0) | 1.053 |

| Female | 84 (54.9) | 72 (49.0) | |

| Skin type of upper inner arm | |||

| 1-2 | 114 (74.5) | 113 (76.9) | 0.426 |

| 3-4 | 31 (20.3) | 26 (17.7) | |

| 5-6 | 7 (4.6) | 8 (5.4) | |

| Did not respond | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

Analysis of variance followed by the Tukey test.

P = .05.

P = .01.

Attrition

Of the 300 caregiver-child pairs who completed assessments at baseline, 280 finished assessments at follow-up (93.3% retention rate). To test for attrition bias, the caregiver-child pairs who did not complete assessments at follow-up were compared with those who did complete assessment at follow-up on baseline measures. The χ2 test was performed for categorical variables (eg, race), and the t test was performed for continuous variables (eg, sunscreen use). Owing to the number of analyses performed, an adjusted P value of less than .01 was used to determine statistical significance. The control and intervention groups were compared based on demographic characteristics and other baseline variables, with the χ2 test used for categorical variables (eg, race) and the t test used for continuous variables (eg, skin sensitivity to sun).

Compared with the caregiver-child pairs who completed the study, those who were lost to attrition did not differ based on any demographic characteristics. Caregivers who were lost to attrition had significantly lower baseline scores of care-givers' perceptions of their own risk of getting skin cancer (t = 3.279; P = .001) and reported that their children were less likely to wear a hat on a sunny day (t = −3.174; P = .004) and less likely to use sunscreen on a cloudy day (t = −2.219; P = .03).

Intervention Effects

Of the 153 caregiver-child pairs in the intervention group, 95 caregivers (62.1%) reported reading the read-along book with their child within 1 week of the baseline visit, and 88 children (57.5%) wore the study-providedswimshirtwithin3 weeks of the baseline visit. There were no significant differences between intervention and control groups in duration of outdoor activity or in the number of children who had sunburn or skin irritation over the study period (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of Sun Protection Behaviors, Melanin Indices, Durations of Outdoor Activities, and Incidences of Sunburn and Skin Irritation Between Control and Intervention Groups.

| Variable | Mean (SD) | P Value for Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Group | Intervention Group | ||||

| Baseline (n = 147) | Follow-up (n = 143) | Baseline (n = 153) | Follow-up (n = 147) | ||

| Sunny day,a Likert scale score | |||||

| Sunscreen | 3.68 (1.14) | 3.66 (1.16) | 3.60 (1.13) | 3.93 (1.05) | .03 |

| Shirt | 3.74 (0.92) | 3.57 (1.15) | 3.66 (0.88) | 3.84 (1.07) | .04 |

| Hat | 2.71 (1.22) | 2.57 (1.25) | 2.53 (1.11) | 2.56 (1.23) | .55 |

| Sunglasses | 2.58 (1.15) | 2.36 (1.09) | 2.64 (1.14) | 2.62 (1.17) | .10 |

| Shade | 2.81 (1.03) | 2.67 (0.88) | 2.60 (0.91) | 2.79 (0.97) | .06 |

| Composite score (5-25) | 15.50 (3.57) | 14.78 (3.47) | 15.03 (3.24) | 15.75 (3.02) | .002 |

| Cloudy day,a Likert scale score | |||||

| Sunscreen | 2.90 (1.32) | 2.73 (1.19) | 3.00 (1.23) | 3.27 (1.20) | .001 |

| Shirt | 3.71 (0.97) | 3.67 (1.18) | 3.60 (0.95) | 3.76 (1.04) | .15 |

| Hat | 2.31 (1.11) | 2.42 (1.12) | 2.15 (1.06) | 2.35 (1.19) | .20 |

| Sunglasses | 2.23 (1.14) | 1.99 (1.01) | 2.41 (1.08) | 2.36 (1.16) | .12 |

| Shade | 2.55 (1.01) | 2.52 (0.93) | 2.44 (0.96) | 2.56 (1.03) | .27 |

| Composite score (5-25) | 13.63 (3.95) | 12.850 (3.61) | 14.02 (3.44) | 14.29 (3.34) | .01 |

| Melanin indexa,b (95% CI), nm | |||||

| Outer upper arm | |||||

| Skin type 1 (n = 133) | 180.15 (58.30) | 209.42 (73.13) | 196.24 (101.48) | 199.38 (106.11) | .001 |

| Skin type 2 (n = 83) | 310.47 (114.05) | 352.00 (148.75) | 287.91 (287.91) | 299.02 (299.02) | .01 |

| Skin type 3 (n = 31) | 397.17 (132.42) | 432.64 (129.62) | 406.79 (152.73) | 436.74 (193.94) | .80 |

| Skin types 4-6 (n = 31) | 645.67 (195.21) | 770.33 (177.63) | 668.69 (245.00) | 667.44 (251.49) | .001 |

| Forearm | |||||

| Skin type 1 (n = 133) | 222.18 (65.03) | 256.72 (71.26) | 223.24 (97.48) | 247.80 (107.14) | .18 |

| Skin type 2 (n = 83) | 352.47 (137.33) | 377.68 (125.71) | 323.09 (103.41) | 346.64 (105.09) | .85 |

| Skin type 3 (n = 31) | 437.17 (111.90) | 458.83 (126.84) | 422.53 (158.80) | 459.53 (150.28) | .46 |

| Skin types 4-6 (n = 31) | 696.40 (154.47) | 761.13 (138.37) | 681.94 (203.47) | 706.81 (195.70) | .06 |

| Duration of outdoor activities,c h | |||||

| Weekdays | 3.46 (1.05) | 3.54 (1.63) | 3.05 (1.86) | 3.69 (1.55) | .44 |

| Weekends | 4.08 (2.10) | 4.05 (1.56) | 4.02 (1.4) | 4.07 (1.60) | .91 |

| Sunburn/skin irritation,d No. (%) | 47 (32.0%) | 31 (21.7) | 51 (33.3) | 45 (30.6%) | .77,e.16f |

Analysis of variance followed by the Tukey test.

Skin type determined by participant's color bar selection.

Two-tailed t test comparing control group with intervention group at follow-up only.

Determined by use of the χ2 test.

At baseline.

At follow-up.

Sunny-Day Behavior Scores

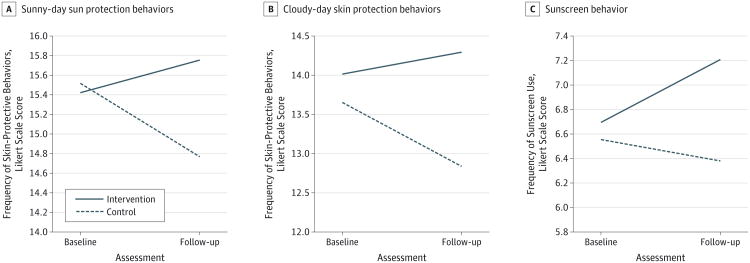

The ANOVA showed a significant interaction of time by group (F1,277 = 10.220; P < .01; η2 = 0.036) (Figure 3A). At baseline, the control group had higher scores related to sunny-day skin protection behaviors (mean difference between intervention and control, −0.071). Post hoc Tukey test results revealed that while the increase in behavior scores in the intervention group were statistically significant (mean difference between follow-up and baseline, 0.72), the control group significantly decreased their behavior scores (mean difference between follow-up and baseline, −0.72). The intervention group had significantly higher scores related to sun protection behaviors at follow-up compared with the control group (mean [SE], 15.748 [0.267] for the intervention group; mean [SE], 14.780 [0.282] for the control group; mean difference, 0.968).

Figure 3. Sun Protection Behaviors.

Change in composite Likert scale scores from baseline to follow-up in control and intervention groups for (A) sunny-day behaviors (range, 5-25); (B) cloudy-day behaviors (range, 5-25); and (C) sunscreen behavior (range, 2-10).

Cloudy-Day Behavior Scores

At follow-up, the intervention group had significantly higher skin protection behavior scores during cloudy days than did the control group (mean [SE], 14.286 [0.282] for the intervention group; mean [SE], 12.850 [0.297] for the control group; mean difference, 1.436) (ANOVA: F1,278 = 8.054; P < .01; η2 = 0.028) (Figure 3B). These analyses controlled for any differences in cloudy-day behavior scores at baseline. Similar to sunny-day behavior scores, the intervention group increased their scores related to sun protection behaviors on cloudy days over the study period (mean difference between follow-up and baseline, 0.266), whereas the control group significantly decreased their scores related to sun protection behaviors from baseline to follow-up (mean difference, -0.782).

Skin Protection Behavior Scores

At follow-up, the intervention group had significantly higher scores related to sunscreen use than did the control group (mean [SE], 7.197 [0.174] for the intervention group; mean [SE], 6.383 [0.182] for the control group; mean difference between intervention and control groups, 0.814) (ANOVA: F1,278 = 10.411; P < .01; η2 = 0.036) (Figure 3C). The intervention group significantly increased their scores related to sunscreen use (mean difference between baseline and follow-up, 0.496). The ANOVAs were not significant for seeking shade or for wearing shirts, hats, or sunglasses.

Individual Sun Protection Behaviors

The ANOVA of the interaction of group by time revealed significant interactions for 3 items: (1) sunscreen use on sunny days (F1,277 = 4.912; P < .05; η2 = 0.017); (2) sunscreen use on cloudy days (F1,278 = 11.416; P < .01; η2 = 0.039); and (3) wearing a shirt with sleeves on sunny days (F1,275 = 4.185; P < .05; η2 = 0.015). At follow-up, the intervention group had (1) significantly higher scores related to sunscreen use on sunny days (mean [SE], 3.932 [0.091] for the intervention group; mean [SE], 3.659 [0.096] for the control group; mean difference, 0.273); (2) significantly higher scores related to sunscreen use on cloudy days (mean [SE], 3.265 [0.099] for the intervention group; mean [SE], 2.729 [0.104] for the control group; mean difference, 0.536); and (3) significantly higher scores related to wearing a shirt with sleeves on sunny days (mean [SE], 3.837 [0.091]; for the intervention group; mean [SE], 3.569 [0.0.97] for the control group; mean difference, 0.268).

Melanin Indices

The ANOVAs examining change in melanin index across skin types (1, 2, and 3 for lighter skin colors and 4, 5, and 6 for darker skin colors) were exploratory owing to the slightly lower number of children in several skin-type categories. Results revealed significant increases in the melanin index in the control group from baseline to follow-up that were not observed in the intervention group with regard to the skin on the outer upper arm (Table 2). Follow-up Tukey test results revealed significant higher mean differences (all P = .05) from baseline to follow-up for the control group for type 1 (29.269 nm), type 2 (41.530 nm), and types 4, 5, and 6 skin (124.666 nm). There were no other significant differences in change in melanin index between the control and intervention groups with regard to the skin on the forearm.

Discussion

This multicomponent skin protection program (composed of a read-along book, a sun-protective swim shirt, and weekly sun protection text messages) increased the number of children who practiced sun protection behaviors over the summer, on both sunny and cloudy days. Children who were in the intervention group were more likely to use sunscreen and wear a shirt with sleeves. Across all skin types, the intervention group had significantly less change in the melanin index on the sun-protected upper arm than did the control group.

While more children in the intervention group were reported by caregivers to engage in sun protection behaviors, fewer children in the control group were reported by care-givers to engage in sun protection behaviors. The sun-protective habits of the control groups' families may have deteriorated over the summer for reasons related to the inconvenience of sun protection behaviors, particularly sunscreen use because it is the most common form of sun protection.6,16-19 Notably, the intervention prevented this deterioration in sun protection behaviors and significantly increased overall sunscreen use.

Previous attempts to improve summertime sun protection behaviors among caregivers and young children via increased counseling at a pediatric clinic were not effective.20,21 The lack of effect of counseling may contribute to 0.01% of pediatrician visits, including sun protection counseling.22 Promisingly, other randomized controlled clinical trials with distribution of sun protection products (eg, sunscreen and clothing) increased parental knowledge and practice of sun protection behaviors.23-25 However, none of these studies evaluated whether children receiving the intervention experienced less pigment change. In addition, the interventions in those studies tended to rely on a combination of regular follow-up and counseling in pediatric clinics.

Our multicomponent sun protection programis unique in several aspects. It significantly increased caregiver-reported sun protection behaviors without clinicians providing anticipatory guidance. Regular text messages reinforced behavior change. Furthermore, the read-along book may have prompted children to request sun protection from their caregivers. To corroborate the survey results and provide a biologic end point of efficacy, melanin indices were monitored over time. The children in the intervention group had significantly lower increases in the melanin index on the upper arm that was covered by the shirt, which provided biological support for the survey results showing that children in the intervention group were more likely to wear a shirt with sleeves. The lack of difference in the change in the melanin index on the forearm between the control and intervention groups may be due to a failure to use sunscreen on the forearm that was not covered by the shirt or may be due to the use of sunscreens that do not completely block UV radiation.

Despite the present study's strengths, there are a few limitations to note. First, although there is very low incentive to be gained by participants' attempting to deceive study staff members, there is always a small possibility that the caregivers' reported data may have been influenced by social desirability bias. Second, the Cronbach α values for the sunny-day and cloudy-day behavior Likert scale scores were relatively low at baseline and follow-up. This suggests that participants did not engage in all the sun protection behaviors equally but, perhaps, displayed preferences that drove changes in the composite scale scores. Lastly, although the participant population was ethnically heterogeneous, the relatively small number of children in each minority group prevented an ethnically stratified analysis of the data. Future studies should examine whether the intervention affected behavior equally among the different ethnic groups. Finally, the number of children in some of the skin-type groups was lower than desired. Future studies would benefit by expanding on these findings with larger samples of children in each skin-type group.

Conclusions

The 2014 Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care of the American Academy of Pediatrics state that age-specific anticipatory guidance is to be performed at every well-child visit.26 Pediatricians' seasonal age-specific sun protection recommendations will be more effective if supported by an effective, easily accessible, multicomponent program that can be reinforced at home. Because pediatricians distribute read-along books to improve literacy, they may distribute a book focusing on sun protection in the spring and summer and incur similar costs in doing so.27-29 Fostering sun protection behaviors in childhood may help children decrease their future risk of skin cancers. The multicomponent program presented in this study (composed of regular text-message reminders, a read-along book, and a swim shirt) was effective in increasing sun protection behaviors while minimizing biologic measures of sun damage (namely, the melanin index).

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Question

How can pediatricians improve sun protection behaviors among young children?

Findings

In this summertime randomized clinical trial of 300 children and their caregivers, families that received read-along books emphasizing sun protection, sun-protective shirts, and weekly text-message reminders related to sun protection behaviors reported statistically significantly higher sun protection behavior scores. Children in the intervention group also had significantly less pigment darkening of the upper outer arm protected by the shirt.

Meaning

Pediatric anticipatory sun protection guidance can be augmented by distributing handouts that include age-specific information about sun protection.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This research initiative is funded by the Pediatric Sun Protection Foundation, Inc.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding agency had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional Contributions: We greatly appreciate the help of all the study participants, as well as the research assistance provided by Francisco Acosta, BA, Yanina Guevara, BA, Rachel Rockwell, BA, and Sara Tayazime, BA, all of whom were affiliated with the Department of Dermatology at Northwestern University during this study and were paid as salaried employees with funding provided by the sponsor. In addition, we appreciate the support of Advocate Health Care in allowing accrual of caregivers and their children in 2 ambulatory pediatric clinics.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Drs Turrisi and Robinso had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Reidy, Crawford, Turrisi, Robinson.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Ho, Reidy, Huerta, Dilley, Crawford, Hultgren, Mallett, Turrisi.

Drafting of the manuscript: Ho, Huerta, Hultgren, Turrisi, Robinson.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Ho, Reidy, Huerta, Dilley, Crawford, Mallett, Turrisi.

Statistical analysis: Ho, Hultgren, Turrisi. Obtained funding: Robinson.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Reidy, Huerta, Dilley, Crawford, Robinson.

Study supervision: Reidy, Huerta, Turrisi, Robinson.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Disclaimers: Dr Robinson is the Editor of JAMA Dermatology. She was not involved in the editorial review or decision to accept this manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Diao DY, Lee TK. Sun-protective behaviors in populations at high risk for skin cancer. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2013;7:9–18. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S40457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Cancer StatisticsWorking Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999-2011. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Cancer Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dennis LK, Vanbeek MJ, Beane Freeman LE, Smith BJ, Dawson DV, Coughlin JA. Sunburns and risk of cutaneous melanoma: does age matter? a comprehensive meta-analysis. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(8):614–627. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elwood JM, Jopson J. Melanoma and sun exposure: an overview of published studies. Int J Cancer. 1997;73(2):198–203. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19971009)73:2<198::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balk SJ, O'Connor KG, Saraiya M. Counseling parents and children on sun protection: a national survey of pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):1056–1064. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall HI, McDavid K, Jorgensen CM, Kraft JM. Factors associated with sunburn in white children aged 6 months to 11 years. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(1):9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallagher RP, Rivers JK, Lee TK, Bajdik CD, McLean DI, Coldman AJ. Broad-spectrum sunscreen use and the development of new nevi in white children: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(22):2955–2960. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.22.2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith A, Harrison S, Nowak M, Buettner P, Maclennan R. Changes in the pattern of sun exposure and sun protection in young children from tropical Australia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(5):774–783. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison SL, Buettner PG, Maclennan R. The North Queensland “Sun-Safe Clothing” study: design and baseline results of a randomized trial to determine the effectiveness of sun-protective clothing in preventing melanocytic nevi. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(6):536–545. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.State and County QuickFacts. [Accessed January 8, 2016]; US Census Bureau website. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/index.html.

- 11.Andrade AC, Onate A, Reidy K, Hultgren B. Sun protection read-along books to support pediatricians' anticipatory guidance. Patient Educ Couns. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eilers S, Bach DQ, Gaber R, et al. Accuracy of self-report in assessing Fitzpatrick skin phototypes I through VI. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(11):1289–1294. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho BK, Robinson JK. Color bar tool for skin type self-identification: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(2):312–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16(3):297–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaccard J. Interaction Effects in Factorial Analysis of Variance. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cokkinides V, Weinstock M, Glanz K, Albano J, Ward E, Thun M. Trends in sunburns, sun protection practices, and attitudes toward sun exposure protection and tanning among US adolescents, 1998-2004. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):853–864. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saraiya M, Glanz K, Briss PA, et al. Interventions to prevent skin cancer by reducing exposure to ultraviolet radiation: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(5):422–466. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahé E, Beauchet A, de Maleissye MF, Saiag P. Are sunscreens luxury products? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(3):e73–e79. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banks BA, Silverman RA, Schwartz RH, Tunnessen WW., Jr Attitudes of teenagers toward sun exposure and sunscreen use. Pediatrics. 1992;89(1):40–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen L, Brown J, Haukness H, Walsh L, Robinson JK. Sun protection counseling by pediatricians has little effect on parent and child sun protection behavior. J Pediatr. 2013;162(2):381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhave N, Reidy K, Randall Kinsella T, Brodsky AL, Robinson JK. Caregivers' response to pediatric clinicians sun protection anticipatory guidance: sun protective swim shirts for 2-6 year old children. J Community Med Health Educ. 2014;4(4):316–325. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akamine KL, Gustafson CJ, Davis SA, Levender MM, Feldman SR. Trends in sunscreen recommendation among US physicians. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(1):51–55. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.4741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crane LA, Deas A, Mokrohisky ST, et al. A randomized intervention study of sun protection promotion in well-child care. Prev Med. 2006;42(3):162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glasser A, Shaheen M, Glenn BA, Bastani R. The sun sense study: an intervention to improve sun protection in children. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34(4):500–510. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.34.4.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buller DB, Burgoon M, Hall JR, et al. Using language intensity to increase the success of a family intervention to protect children from ultraviolet radiation: predictions from language expectancy theory. Prev Med. 2000;30(2):103–113. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker Cynthia, Barden Graham A, III, Brown OW, et al. Simon Geoffrey R Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine; Bright Futures Periodicity Schedule Workgroup. 2014 recommendations for pediatric preventive health care. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):568–570. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-4096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golova N, Alario AJ, Vivier PM, Rodriguez M, High PC. Literacy promotion for Hispanic families in a primary care setting: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 1999;103(5, pt 1):993–997. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.5.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Needlman R, Fried LE, Morley DS, Taylor S, Zuckerman B. Clinic-based intervention to promote literacy: a pilot study. Am J Dis Child. 1991;145(8):881–884. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1991.02160080059021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanders LM, Gershon TD, Huffman LC, Mendoza FS. Prescribing books for immigrant children: a pilot study to promote emergent literacy among the children of Hispanic immigrants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(8):771–777. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.8.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.