Abstract

Autophagy and apoptosis are the two major modes of cell death, and autophagy usually inhibits apoptosis. The current understanding has shown that there is a complex crosstalk between the components of these two pathways. Here, we describe a transcriptional mechanism that links autophagy to apoptosis. We show that the cisplatin-resistant MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 osteosarcoma sublines, in comparison to their parental MG63 and U2OS cells, respectively, exhibit increased autophagy but decreased apoptosis levels after treatment with cisplatin. We then used a microarray assay to examine the gene expression changes in these two cisplatin-resistant sublines and found that the expression of the transcription factor FOXO3a was dramatically decreased. Pharmacological treatment with either 3-methyladenine to inhibit autophagy or with rapamycin to activate autophagy in these two cisplatin-resistant sublines resulted in the accumulation or degradation of FOXO3a, respectively. Ectopic expression of FOXO3a in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells significantly enhanced cell sensitivity to cisplatin through a mechanism in which FOXO3a directly binds to the PUMA promoter and activates its expression, as well as its downstream event, the intrinsic apoptosis pathway. Importantly, this overexpression resulted in tumor growth inhibition in vivo. In conclusion, our results provide new insights into the molecular link between autophagy and apoptosis that involves a FOXO3a-mediated transcriptional mechanism. Importantly, our results may facilitate the development of therapeutic strategies for osteosarcoma patients who have become resistant to cisplatin therapy.

Keywords: FOXO3a, cisplatin, PUMA, autophagy, apoptosis, osteosarcoma

Introduction

Autophagy and apoptosis are two well-known cell death processes that play important roles in controlling cell development and differentiation, tissue homeostasis and diseases [1,2]. The process of autophagy includes several distinct stages: (1) the damaged cell organelles or unused proteins are enclosed by a phagophore or isolation membrane; (2) a double membrane is created, forming the autophagosome; (3) the outer membrane subsequently fuses with the endosome and then with the lysosome; (4) the damaged cell organelles or unused proteins are degraded. Autophagy is executed by a number of autophagy-related (Atg) genes [3-5]. Two kinases, including the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), can regulate autophagy through the inhibitory phosphorylation of two Unc-51-like kinases, ULK1 and ULK2 (a homologue of Atg1) [6,7]. Atg13 binds both ULK1 and ULK2 and mediates the interaction of the ULK proteins with the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) family kinase-interacting protein of 200 KDa (FIP200) [8]. In addition, ULKs can phosphorylate and activate Beclin-1, a homologue of Atg6, which further forms a complex with Atg14L, p150 and the class III phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate kinase VPS34, contributing to the activation of downstream autophagy components [9]. Two ubiquitin-like conjugation systems are also involved in autophagy. Atg12, an ubiquitin-like protein, is conjugated to the substrate Atg5 by Atg7 and Atg10 [10]. The resulting conjugate protein complex further binds Atg16 to form an E3-like complex, which binds and activates Atg3 and functions as part of the second ubiquitin-like conjugation system [10]. Atg3 further covalently attaches to Atg8, the most studied being the LC3 proteins, and it is located in the lipid phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) on the surface of autophagosomes. Lipidated LC3 contributes to the closure of autophagosomes and enables the docking of specific cargos and adaptor proteins such as Sequestosome-1/p62 [11].

Apoptosis is a complicated process that includes two main signaling pathways: the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways [12-14]. The extrinsic pathway is initiated on the cell surface by activating pro-apoptotic receptors, such as tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1), death receptors (DRs) and Fas [12-14]. This pathway contains several other proteins, including membrane-bound Fas ligand (FasL), Fas complexes, Fas-associated death domain (FADD), caspase-8 and -10; these proteins ultimately activate downstream caspases and trigger apoptosis [12-14]. Previous studies have demonstrated that ligand binding induces receptor clustering and the recruitment of the adaptor protein FADD and the initiator caspases-8 and -10 as procaspases, forming the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) [12-14]. This event triggers the activation of the apical caspases including caspase-8 and -10, driving their autocatalytic processing and release into the cytoplasm, where they activate the effector caspases-3, -6 and -7 [12-14]. The intrinsic pathway is initiated on the mitochondria [15,16]. In response to DNA damage or cellular stresses, the tumor suppressor p53 activates cell death through the modulation of PUMA and BAX, leading to mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), cytochrome c release, and the formation of the Apaf-1 apoptosome, which in turn activates caspase-9 and initiates the activation of caspase cascades [15,16].

Accumulating evidence has indicated crosstalk among the components of these two pathways, which results in their cooperation or opposition of each other [2,17,18]. For instance, the inhibition of mTOR results in the induction of autophagy, while mTOR also has pleiotropic effects on apoptosis through diverse downstream targets, such as p53, BAD and BCL-2 proteins [2,19]. Beclin 1, the mammalian ortholog of yeast autophagy protein 6 (Atg6), can mediate the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis through interaction with BCL-2 and BCL-XL [20]. Caspases are the executioners of apoptosis, and it has been found that caspases can mediate the cleavage of Beclin 1 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), resulting in the inactivation of Beclin-1-induced autophagy but enhancing apoptosis by promoting the release of proapoptotic factors from the mitochondria [21]. In addition, the anti-apoptotic protein FLIP (Flice inhibitory protein) can function as a suppressor of autophagy through their inhibitory interaction with ATG3, preventing the ATG3-mediated elongation of autophagosomes [22].

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary bone cancer that occurs in teenagers and young adults [23,24]. Osteosarcoma is often treated with a combination of therapies that include surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy [25]. Chemotherapy often results in drug resistance, which reduces patient survival rates. To investigate the molecular mechanism of chemotherapeutic resistance in osteosarcoma cells, we screened and obtained several cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cell lines. After examining the cell viabilities of these cisplatin-resistant cells, we selected the MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cell lines for further studies. Our results indicate that the inhibition of autophagy results in the increased expression of FOXO3a, which directly binds to the PUMA promoter region and positively regulates the expression of PUMA, eventually activating the p53-independent apoptotic pathway. Our findings reveal a new signaling pathway for the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis, which will provide a potential new route for combining cancer drugs and autophagy inhibitors in osteosarcoma chemotherapy.

Material and methods

Cell lines, culture conditions, and transfection

Human osteosarcoma cancer cell lines MG63 and U2OS were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA) and maintained in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.1% penicillin/streptomycin, and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. The cisplatin-resistant MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5, derived from MG63 and U2OS, respectively, were developed by continuously exposing single cell to cisplatin (10 μM) for 3 months, at which point cells regained morphology similar to the parental line. The MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells were maintained in DMEM medium supplemented with 10 μM cisplatin, a concentration at which parental cells are not viable.

For overexpressing FOXO3a in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells, cells under approximately 80% confluent were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, USA) in suspension with 200 ng of pCDNA3-FOXO3a plasmid. The transfected cells were immediately plated into 12-well plates supplemented with 1.0 ml of DMEM medium and incubated at 37°C for 48 h, then subjected to the required experiments.

Pharmacological reagent treatments

For cisplatin treatment, cells were first seeded into 96-well plates for 24 h. Then, the culture medium was replaced with 0.1 ml of fresh medium containing 0.5% FBS and the same medium containing different concentrations of cisplatin (0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100 μM, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for another 72 h. The cell viability was determined using the CellTiter96 AQueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After reading the signals in all wells at 490 nm with a microplate reader, the percentages of surviving cells in each well were calculated by defining the control as 100%.

For 3-methyladenine (3-MA) and Rapamycin treatments, the cells were first seeded into 96-well plates for 24 h and then treated with 5 mM 3-MA for another 9 h or with 500 nM Rapamycin for another 24 h. The cells were then harvested, lysed, and subjected to immunoblot analysis.

Immunoblot analysis

The immunoblot analysis was performed as previously descripted [24]. In brief, cells were lysed and sonicated in 1 × RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) supplemented with 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 × complete protease cocktail inhibitor (Roche, USA). Proteins were boiled at 95°C for 10 min, and then equal amount of proteins were loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel for separation. Antibodies used for western blots were as follows: β-Actin, FOXO3a, p53, Bcl-2 and Bax (mouse, Sigma, USA); PARP (rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology, USA); Caspase 3, LC3, p62, ATG5, ATG7, and PUMA (rabbit, Sigma, USA). The western blot signals were detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (GE Healthcare, USA) with a ChemiDoc MP instrument (Bio-Rad, USA). The images represent three independent replicates.

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis were performed as previously described [26]. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA concentration was measured using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). After treatment with DNase I to remove the contaminated DNA, a total of 500 ng RNA was used as the template to synthesize the first-strand cDNA with the oligo(dT) primer and M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, USA). The resulting cDNAs were subjected to qRT-PCR analysis using the Bio-rad SYBR Green Master Mix kit (Bio-Rad, USA). The expression of β-actin mRNA was selected as an internal control. Primers were listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Microarray analysis

Global-scale gene expression analysis was performed using a GeneChip Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array System (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA), which covers more than 47,000 human gene transcripts. In brief, a total of 500 ng RNA treated with DNase I was synthesized into biotin-labeled cRNA using a GeneChip 3’ In Vitro Transcription (IVT) Express Kit (Affymetrix Inc., USA). The biotin-labeled cRNA was then fragmented and hybridized to the array chip at 45°C for 16 h. The arrays were washed, stained with streptavidin-phycoerythrin (SAPE) for 300 seconds at 35°C, and scanned using a GeneArrayTM Scanner. The significantly changed genes were obtained by examining the hybridization intensity data using GeneSpring GX (Agilent Technologies Inc., USA).

Luciferase assay

The MG63-R12, U2OS-R5, and these two cell lines overexpressing FOXO3a, were co-transfected the firefly luciferase reporter vector pGL4.26-PPUMA-WT-Luc or pGL4.26-PPUMA-Mutant-Luc with the renilla luciferase vector pRL-TK, respectively. The transfected cells were incubated at 37°C for 24 hrs, then subjected to luciferase assay using a Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, USA) according to the manufacturer’s manual. The relative luciferase activity was determined by normalization of firefly luciferase activity against the renilla luciferase.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

Cells under approximately 80% confluent were washed twice with 1 × PBS at room temperature, followed by crosslink with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by the supplementation of glycine (final concentration of 0.125 M). After washing twice with 1 × PBS, cells were lysed in a hypothonic buffer containing 1% NP40, 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 × proteinase inhibitor. Following sonication for 2 min at 4°C, cell lysate was centrifuged in a speed of 13000 g for 10 min. A total of 50 μl supernatant was taken out as input, the remaining part was incubated with Protein A-Sepharose beads (Sigma, USA) and FOXO3a antibody at 4°C. After 12 h, the Protein A beads were washed five times with a buffer containing 20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% TritonX-100, and 1 × proteinase inhibitor. The resulting beads were then eluted with a buffer containing 1 mM sodium bicarbonate and 1% SDS. DNA was precipitated by two-fold volume of ice ethanol, followed by purification with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, USA). The purified DNA was subjected to qRT-PCR analysis using the Bio-rad SYBR Green Master Mix kit (Bio-Rad, USA). PCR was performed with primers listed in Supplementary Table 2.

In vivo tumor formation assay

Two-month-old female athymic nu/nu mice from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China) were maintained following the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Shanghai Jiao Tong University. 1 × 106 cells from each cell line (MG63, MG63-R12, U2OS or U2OS-R5), were suspended in 100 μl of Matrigel Matrix (BD Biosciences, USA) and diluted with 1 × PBS to a 1:1 ratio. The resulting cell suspension was injected intradermally into the flank of the mice (two tumors per mouse, five mice per group). Tumor volume was measured with fine calipers at 5-day intervals and calculated with the formula: Volume = (Length × Width 2)/2.

Statistical analysis

All experiments in this study were independently replicated at least three times. Statistical analyses of the experimental data were performed using a two-sided Student’s t test. Significance was set at the P < 0.05.

Results

Cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma sublines have increased autophagic levels than their parental lines

After a period of chemotherapy, osteosarcoma patients often show increased resistance against chemotherapeutic drugs including cisplatin. To investigate the underlying mechanism, we used the MG63 and U2OS cell lines as parental cells, and continuously exposed them to 10 μM cisplatin for 3 months with a change of fresh medium every 3 days. Finally, we obtained a total of 7 cisplatin-resistant sublines. Four of them were from the MG63 background, including MG63-R1, -R12, -R23, and -R35, and the other three, U2OS-R5, -R20, and -R33, were from the U2OS background. By examining the cell viabilities of these cisplatin-resistant sublines in different concentrations of cisplatin (0, 1, 10, 50 and 100 μM) compared to their parental cell lines, we found that the cell lines MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 showed the strongest resistance against cisplatin (Supplementary Figure 1) under treatment with 50 and 100 μM cisplatin. Thus, we chose the cell lines MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 as the cells for further investigation.

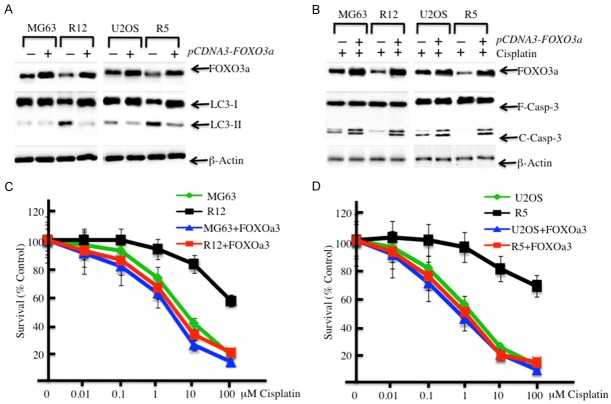

To evaluate the cell viabilities of the MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cell lines, we treated the cells with different concentrations of cisplatin. Compared to their parental lines, the MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells were significantly insensitive to cisplatin-induced growth inhibition (Figure 1A). The IC50 values of cisplatin were approximately 8.35 μM ± 0.13 in MG63 cells vs. 121.07 μM ± 0.96 in MG63-R12 cells and 9.04 μM ± 0.29 in U2OS cells vs. 127.77 μM ± 1.19 in U2OS-R5 cells (P < 0.05). As cisplatin can induce cell apoptosis, we also evaluate the cleavage levels of PARP and caspase-3, two hallmarks of apoptosis. Our results indicated that cisplatin induced the profound cleavage of PARP and caspase-3 in MG63 and U2OS cells, but the cleavage of PARP in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells was significantly reduced with the treatment of cisplatin in comparison to their parental cell lines (Figure 1B). More significantly, the cleavage of caspase-3 was completely absent in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells, even in the presence of cisplatin, whereas it was obvious in their parental cell lines (Figure 1B). These data indicate that MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells are refractory to cisplatin-induced growth inhibition and apoptosis. One possibility for the reduced apoptosis of MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells is the increased autophagic level because autophagy usually inhibits apoptosis. To verify this hypothesis, we also examined the autophagy statuses in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells with or without cisplatin treatment. Western blot analysis was used to measure the ratio of LC3-I and LC3-II, as well as another two autophagic proteins, ATG5 and ATG7. Marked increases in the ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I and the protein levels of ATG5 and ATG7 were observed in cisplatin-resistant cells compared to their parental cells in the absence of cisplatin (Figure 1D). Conversely, with the treatment of cisplatin, the ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I, as well as the ATG5 and ATG7 protein levels, were dramatically decreased in both cisplatin-resistant cells and their parental cells (Figure 1D). Under the same conditions, the ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells was much greater than their parental cells (Figure 1D). These results further suggested that increased autophagy in cisplatin-resistant cells, which may contribute to their growth resistance to cisplatin treatment.

Figure 1.

Cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cells have decreased levels of apoptosis and increased levels of autophagy. (A and B) Cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cells are insensitive to cisplatin treatment. MG63, MG63-R12, U2OS and U2OS-R5 cells were plated in 96-well plates. After 24 hrs, the culture medium was replaced with 0.1 ml of fresh medium containing 0.5% FBS and the same medium containing the indicated concentrations of cisplatin for another 72 hrs. The percentages of surviving cells in each well were calculated by defining the control (MG63 or U2OS, 0 μM cisplatin) as 100%. (C) Cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cells have decreased levels of apoptosis. MG63, MG63-R12, U2OS and U2OS-R5 cells were treated with or without cisplatin (10 μM) for 24 hrs. The cells were collected and subjected to Western blot analyses for PARP (F-PARP, full length PARP; C-PARP, cleaved PARP), caspase-3 (F-Casp-3, full length caspase-3; C-Casp-3, cleaved caspase-3), or β-actin. (D) Cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cells have increased levels of autophagy. The same protein lysates used in (C) were subjected to Western blot to detect the level of LC3, ATG5, ATG7 or β-actin. The data represent three independent experiments.

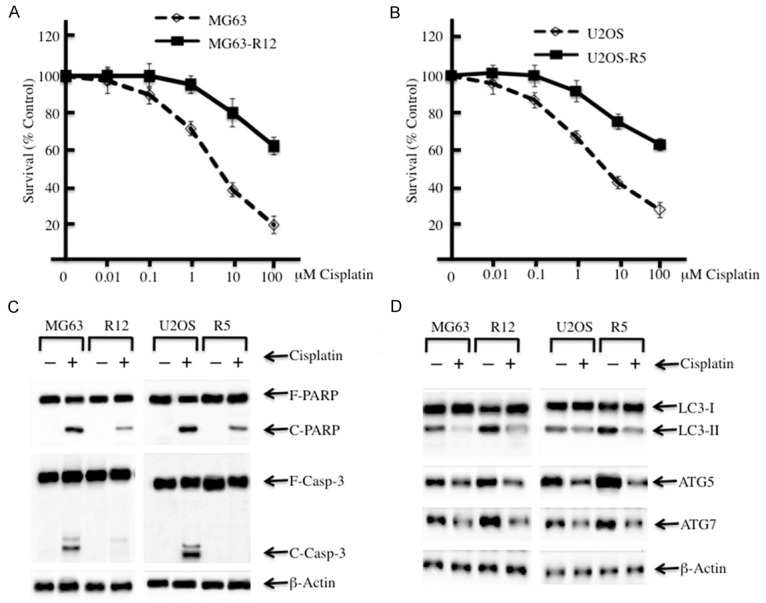

Inhibition of autophagy in cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cancer sublines increases cell sensitivity to cisplatin treatment

As MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells have an increased autophagy status compared to their parental cells, the inhibition of autophagy signaling should result in a similar response to cisplatin treatment. To verify this hypothesis, we primarily treated the cisplatin-resistant and their parental cells with 3-methyladenine (3-MA), an inhibitor of autophagy that blocks autophagosome formation via the inhibition of PI3K, and then examined the autophagy and apoptosis statuses in these cells. Our results indicated that the conversion from LC3-I to LC3-II was completely suppressed in cisplatin-resistant cells and their parental cells with the treatment of 3-MA (Figure 2A). In addition, the ATG5 and ATG7 protein levels were also significantly decreased (Figure 2A). More importantly, these protein levels had no obvious difference between cisplatin-resistant and their parental cells. Next, we further investigated the effects of 3-MA and cisplatin coordinated treatments on the cisplatin-resistant cells. First, we blocked the autophagy process using 5 mM 3-MA treatment for 9 h, and the cells were treated with 10 μM cisplatin medium for another 72 h. Then, the apoptosis status of these cells was examined. Our results indicated that cisplatin-resistant and their parental cells had similar levels of cleaved PARP and caspase-3 (Figure 2B), suggesting that the coordinated treatments of 3-MA and cisplatin resulted in similar apoptosis status in these cells. At the same time, we also evaluated the cell viabilities of MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells and their parental cells under the coordinated treatments of 3-MA and cisplatin. We initially treated cells with 5 mM 3-MA for 9 h and then treated them with different concentrations of cisplatin (0, 0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 10 and 100 μM) for another 72 h. Our results showed that MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells have similar cell viabilities compared to their parental lines after treatment with 3-MA and cisplatin (Figure 2C and 2D). These results further suggested that the higher levels of autophagy in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells were the reason for their resistance to cisplatin.

Figure 2.

The inhibition of autophagy in cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cells enhances their sensitivity to cisplatin. (A) The inhibition of autophagy in cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cells leads to the downregulation of LC3-II, ATG5 and ATG7. MG63, MG63-R12, U2OS and U2OS-R5 cells were plated in 96-well plates. After 24 hrs, the culture medium was replaced with 0.1 ml of fresh medium containing 0.5% FBS and the same medium containing 5 mM 3-MA for another 9 hrs. The cells were collected and subjected to Western blot analyses for LC3, ATG5, ATG7 or β-actin. (B) The inhibition of autophagy in cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cells increased their level of apoptosis. MG63, MG63-R12, U2OS and U2OS-R5 cells were plated in 96-well plates. After 24 hrs, the culture medium was replaced with 0.1 ml of fresh medium containing 0.5% FBS and the same medium containing 5 mM 3-MA for another 9 hrs. Later, the medium was replaced with 0.1 ml of fresh medium containing 0.5% FBS and the same medium containing 10 μM cisplatin for another 72 hrs. The cells were collected and subjected to Western blot analyses of PARP, caspase-3 or β-actin. (C and D) The inhibition of autophagy in cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cells increases their sensitivity to cisplatin. MG63, MG63-R12, U2OS and U2OS-R5 cells were treated as in (B), and then, the percentages of surviving cells in each well were calculated by defining the control (MG63 or U2OS, 0 μM cisplatin) as 100%. The data represent three independent experiments.

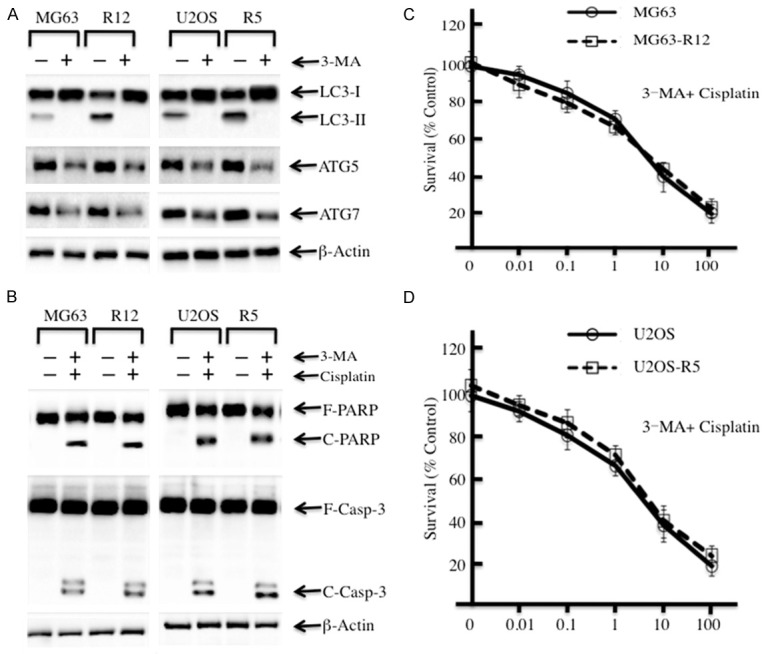

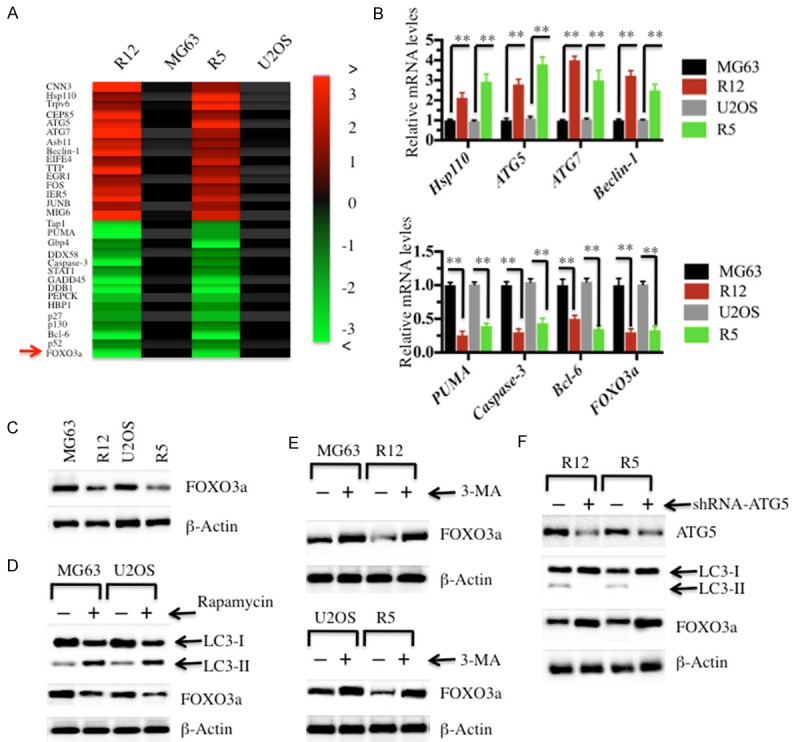

The transcription factor FOXO3a is downregulated cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma sublines

Based on the increased autophagy status of MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells, we next sought to investigate genes that control this process. For this purpose, we subjected the mRNAs from MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells and their parental cells to microarray analysis. The hierarchical clustering analysis revealed distinctive mRNA expression patterns between the cisplatin-resistant cells and their parental cells (Figure 3A). Overall, 435 genes were identified to have aberrant expression in both two cisplatin-resistant cell lines compared to their parental cells (data not shown). Of these genes, 271 genes were upregulated, and the others were downregulated (data not shown). As shown in Figure 3A, we selected 15 upregulated genes and 15 downregulated genes that showed consistent expression patterns in both MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 sublines. Interestingly, of these 15 upregulated genes, we found several of them are critical for autophagy, including ATG5, ATG7 and Beclin-1 (Figure 3A). Of these downregulated genes, we found several of them are important for apoptosis, including PUMA and Caspase-3 (Figure 3A). In addition, we also found that the transcription factor known as FOXO3a was significantly downregulated in both the MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 sublines (Figure 3A). Thus, we selected 8 genes, 4 from the upregulated group (Hsp110, ATG5, ATG7 and Beclin-1) and 4 from the downregulated group (PUMA, Caspase-3, Bcl-6 and FOXO3a), and examined their expression in the MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 sublines by qRT-PCR. Consistent with the microarray results, the expression levels of Hsp110, ATG5, ATG7 and Beclin-1 were upregulated by 2.5-4 fold, whereas the levels of PUMA, Caspase-3, Bcl-6 and FOXO3a were downregulated by 2-4 fold in the MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 sublines compared with their parental cells (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

FOXO3a is downregulated in cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cells. Heat maps of the 30 most significantly (P < 0.01) altered genes in cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cells were shown. (A) The RNA from MG63, MG63-R12, U2OS and U2OS-R5 cells was subjected to miRNA microarray analysis. Each column represents a tissue sample, and each row represents a probe set. The heat maps indicate high (red) or low (green) levels of gene expression. (B) qRT-PCR was performed to verify the expression of Hsp110, ATG5, ATG7, Beclin-1, PUMA, Caspase-3, Bcl-6 and FOXO3a in cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cells. The relative expression of these genes in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells was normalized to their corresponding parental cells (P < 0.001). (C) The FOXO3a protein level was downregulated in cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cells. MG63, MG63-R12, U2OS and U2OS-R5 cells were plated in 96-well plates containing 0.1 ml of 0.5% FBS medium for 24 hrs. The cells were collected and subjected to Western blot analyses for FOXO3a or β-Actin. (D) The activation of autophagy resulted in the downregulation of FOXO3a. MG63, MG63-R12, U2OS and U2OS-R5 cells were plated in 96-well plates. After 24 hrs, the culture medium was replaced with 0.1 ml of fresh medium containing 0.5% FBS and the same medium containing 500 nM rapamycin for another 24 hrs. The cells were collected and subjected to Western blot analyses for LC3, FOXO3a or β-actin. (E and F) The inhibition of autophagy resulted in the accumulation of FOXO3a. MG63, MG63-R12, U2OS and U2OS-R5 cells were treated with or without 3-MA (E), and the MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells were transfected with lentivirus containing either ConshRNA or ATG5-shRNA (F). The cells were collected and subjected to Western blot analyses for FOXO3a, LC3, ATG5 or β-actin. The data represent three independent experiments.

Given that FOXO3a directs a protective autophagy program in hematopoietic stem cells, we next sought to investigate if FOXO3a also participates in the regulation of autophagy in cisplatin-resistant cells. For this purpose, we first examined the FOXO3a protein levels in the MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 sublines. Consistent with the mRNA level, FOXO3a was significantly downregulated in the MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 sublines in comparison to their parental cells (Figure 3C). Next, we wanted to examine if the activation or inhibition of autophagy could affect the FOXO3a protein level. First, we treated MG63 and U2OS cells with rapamycin, a mTOR inhibitor, to activate autophagy to mimic the autophagic condition in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 sublines. The immunoblot results indicated that rapamycin treatment induced autophagy and resulted in the decrease of FOXO3a (Figure 3D). Subsequently, we treated the MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 sublines with 3-MA to inhibit autophagy and then examined the FOXO3a protein level. Our results indicated that the inhibition of autophagy lead to the accumulation of FOXO3a (Figure 3E). In addition, we also blocked autophagy signaling in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 sublines by transfecting the cells with ATG5-shRNA to knockdown ATG5 expression and then detected the FOXO3a level. Interestingly, the blockage of autophagy signaling also resulted in the accumulation of FOXO3a (Figure 3F). These results suggested that the activation or inhibition was able to affect the protein level of FOXO3a.

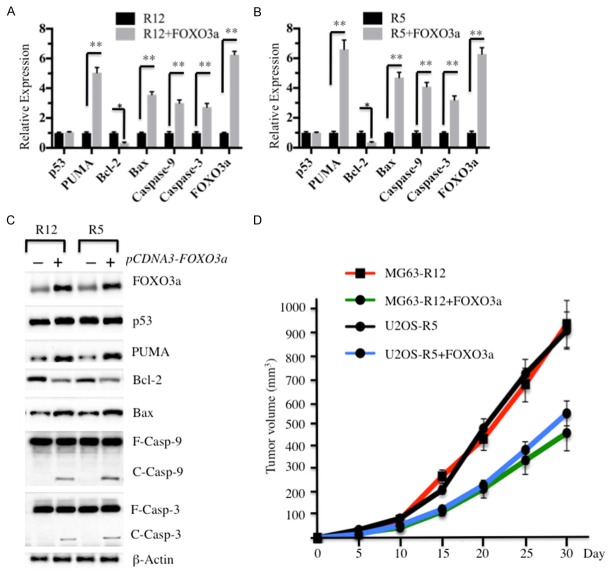

The overexpression of FOXO3a enhances the sensitivity of MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells to cisplatin

Based on the results that MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells have increased autophagy, which contributes to the downregulation of FOXO3a, we next investigated if the overexpression of FOXO3a in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells could affect the autophagy status, as well as enhance the sensitivity of these cells against cisplatin. First, we transfected the overexpression vector pCDNA3-FOXO3a into MG63, MG63-R12, U2OS and U2OS-R5 cells and then examined the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio to evaluate the effect of the FOXO3a protein level on autophagy status. Interestingly, the immunoblot results showed that the overexpression of FOXO3a resulted in a decrease in the autophagy statuses in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells (Figure 4A). Then, we treated cells overexpressing FOXO3a with 10 μM cisplatin and detected the level of apoptosis in these cells. Our results indicated that cisplatin treatment lead to increased cleavage of caspase-3 (Figure 4B), which suggested that cisplatin treatment could increase the level of apoptosis in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells overexpressing FOXO3a. Consistently, we also observed decreased cisplatin resistance in both MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells overexpressing FOXO3a compared to cells without FOXO3a overexpression (Figure 4C and 4D). These results suggested that FOXO3a is critical for the regulation of apoptosis status in cisplatin-resistant cells.

Figure 4.

The overexpression of FOXO3a in cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cells enhances their sensitivity to cisplatin. A: The overexpression of FOXO3a in cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cells resulted in the downregulation of LC3-II. MG63, MG63-R12, U2OS and U2OS-R5 cells were transfected with pCDNA3-FOXO3a plasmid and incubated in medium containing 0.5% FBS. After 24 hrs, the cells were collected and subjected to Western blot analyses for FOXO3a, LC3 or β-Actin. B: The overexpression of FOXO3a in cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cells increases their level of apoptosis. MG63, MG63-R12, U2OS and U2OS-R5 cells were transfected with the pCDNA3-FOXO3a plasmid and incubated in medium containing 0.5% FBS. After 24 hrs, the cells were treated with 10 μM cisplatin for another 72 hrs. The cells were collected and subjected to Western blot analyses for FOXO3a, caspase-3 or β-actin. C and D: The overexpression of FOXO3a in cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cells increased their sensitivity to cisplatin. MG63, MG63-R12, U2OS and U2OS-R5 cells were transfected with the pCDNA3-FOXO3a plasmid, and then, the percentages of surviving cells in each well were calculated by defining the control (MG63 or U2OS, 0 μM cisplatin) as 100%. The data represent three independent experiments.

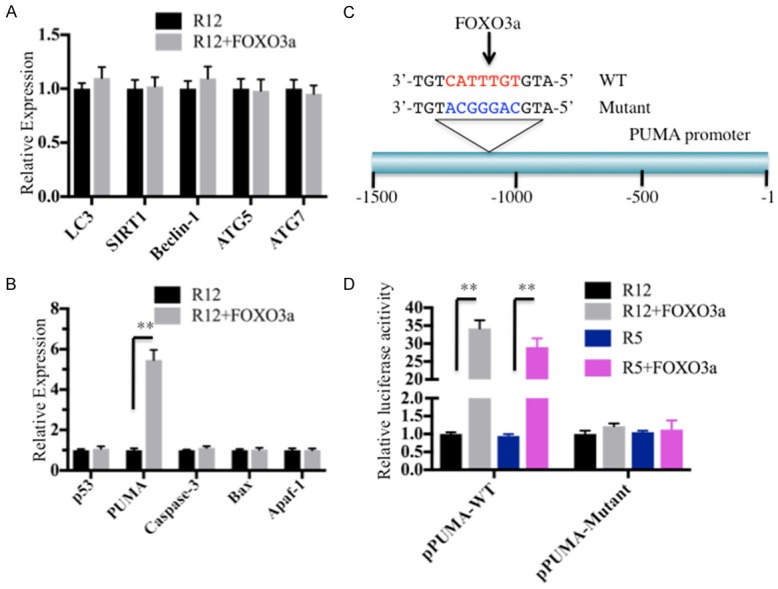

FOXO3a specifically binds to the promoter of PUMA and regulates its expression

Our microarray assay results identified several autophagy genes (ATG5, ATG7 and Beclin-1) that were upregulated and two apoptosis genes (PUMA and Caspase-3) that were downregulated. To examine if FOXO3a could directly regulate the expression of these genes, as well as other critical members involved in the autophagy and apoptosis pathways, such as LC3, SIRT1, p53, Bax and Apaf-1, we performed a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay to detect if FOXO3a could bind to the promoters of these genes. By treating the FOXO3a antibody bound to Protein A agarose to precipitate DNA from MG63-R12 and MG63-R12+FOXO3a cells, the enriched DNAs were detected with qRT-PCR. Our results indicated that no obvious difference was found for the binding of autophagic signaling members, including LC3, SIRT1, ATG5, ATG6 and Beclin-1 in MG63-R12 and MG63-R12+FOXO3a cells (Figure 5A). However, among those autophagic members, we found the expression of PUMA was significantly upregulated in MG63-R12+FOXO3a cells compared to MG63-R12 cells, which suggests that FOXO3a might directly bind to the PUMA promoter region and positively regulate PUMA expression. To verify this conclusion, we analyzed the sequence in the PUMA promoter region to identify if it contained a FOXO3a binding site. Accordingly, we selected a 1,500 bp-promoter region in PUMA and searched for the FOXO3a binding site in the ALGGEN-PROMO database (http://alggen.lsi.upc.es/cgi-bin/promo_v3). By comparing the potential transcription factor binding sites, we found that the PUMA promoter region contained a FOXO3a consensus site (CATTTGT) located at (-1098)-(-1105) bp from the initiation site (Figure 5C). To further verify the binding of FOXO3a to the PUMA promoter, we generated PUMA promoter luciferase reporter constructs containing either with wild type (WT) or mutated FOXO3a-binding sites (Figure 5C). After co-transfecting the pGL4.26-PPUMA-WT-Luc or pGL4.26-PPUMA-Mutant-Luc vector with the Renilla luciferase vector pRL-TK in MG63-R12, MG63-R12+FOXO3a, U2OS-R5 and U2OS-R5+FOXO3a cells, we investigated the contribution of FOXO3a to the activation of PUMA. As shown in Figure 5D, the overexpression of FOXO3a in either MG63-R12 or U2OS-R5 cells activated the expression of PUMA containing the WT promoter but failed to activate the expression of PUMA containing mutated promoter (Figure 5D). These results suggested that FOXO3a was able to directly bind to the promoter of PUMA and modulate its expression.

Figure 5.

FOXO3a binds to the promoter of PUMA and positively regulates its expression. (A) FOXO3a is not able to directly bind to the promoters of the genes involved in autophagic signaling. MG63-R12 and MG63-R12+FOXO3a cells were subjected to a ChIP assay using the FOXO3a antibody, and the binding of autophagic signaling genes, including LC3, SIRT1, Beclin-1, ATG5 and ATG7, was assessed by qRT-PCR. The expression levels of each gene were normalized against the control vector. (B) FOXO3a specifically binds to the promoter of PUMA. The same DNA in (A) was used to examine the binding of apoptotic signaling genes, including p53, PUMA, Bax, Caspase-3 and Apaf-1. (C) A schematic diagram of the PUMA promoter. The promoter region (-1 - -1500) of PUMA is indicated, and the consensus sequence of the FOXO3a binding site is indicated in red. The mutant FOXO3a binding site is indicated in blue. (D) Luciferase assay. MG63-R12, MG63-R12+FOXO3a, U2OS-R5, and U2OS-R5+FOXO3a cells were co-transfected the firefly luciferase reporter vector pGL4.26-PPUMA-WT-Luc or pGL4.26-PPUMA-Mutant-Luc with the Renilla luciferase vector pRL-TK, respectively. After incubation at 37°C for 24 hrs, the cells were subjected to a luciferase assay using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System. The luciferase activities in MG63-R12+FOXO3a and U2OS-R5+FOXO3a cells were normalized against MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells, respectively (**P < 0.001).

Given that PUMA is a key player upstream of intrinsic apoptosis signaling, we next sought to investigate the effect of the FOXO3a level on the apoptosis pathway. Accordingly, we first examined the mRNA levels of intrinsic pathway members, including p53, PUMA, Bcl-2, Bax, Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 in MG63-R12, MG63-R12+FOXO3a, U2OS-R5, and U2OS-R5+FOXO3a cells. Interestingly, we found the levels of PUMA, Bax, Capase-9 and Caspase-3 were significantly increased, while the Bcl-2 mRNA level was dramatically decreased in MG63-R12+FOXO3a and U2OS-R5+FOXO3a cells compared to MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells, respectively (Figure 6A and 6B). However, we did not find an expression change for p53 in these cells (Figure 6A and 6B). Furthermore, we also detected the protein levels in MG63-R12, MG63-R12+FOXO3a, U2OS-R5, and U2OS-R5+FOXO3a cells. Consistently, we also observed the induced levels of PUMA, Bax, cleaved Caspase-9 and Caspase-3, a decreased level of Bcl2, but no change in the p53 level in MG63-R12+FOXO3a and U2OS-R5+FOXO3a cells compared to MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells, respectively (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

The overexpression of FOXO3a activates the p53-independent intrinsic apoptosis pathway. A and B: The overexpression of FOXO3a activates the downstream gene expression of PUMA. The mRNAs from MG63-R12, MG63-R12+FOXO3a, U2OS-R5, and U2OS-R5+FOXO3a cells were used to determine the expression of p53, PUMA, Bcl-2, Bax, Caspase-9, Caspase-3, Apaf-1 and FOXO3a. The relative expression of these genes in cells overexpressing FOXO3a was normalized against the individual gene expression in their corresponding non-overexpression cells (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.001). C: The overexpression of FOXO3a increases the protein levels of PUMA downstream. Cell lysates from MG63-R12, MG63-R12+FOXO3a, U2OS-R5, and U2OS-R5+FOXO3a cells were subjected to Western blot analyses for p53, PUMA, Bcl-2, Bax, Caspase-9, Caspase-3, Apaf-1 and FOXO3a. D: The overexpression of FOXO3a decreases the ability to form tumors in vivo. MG63-R12, MG63-R12+FOXO3a, U2OS-R5, and U2OS-R5+FOXO3a cells were injected intradermally into the flanks of mice. Tumor volumes were measured with fine calipers at 5-day intervals.

Based on the results that the overexpression of FOXO3a activated apoptosis signaling, we next sought to evaluate whether the overexpression of FOXO3a in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 had effects on cell proliferation and sphere formation. As shown in Supplementary Figure 2A, the cell proliferation assay results indicated that the overexpression of FOXO3a in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells significantly inhibited cell growth. The results of the sphere formation assay indicated that the overexpression of FOXO3a in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells lead to a significant decrease in the ability to form spheres (Supplementary Figure 2B). To evaluate if the overexpression of FOXO3a in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells results in similar suppressive effects in vivo, we injected nude mice with MG63-R12, MG63-R12+FOXO3a, U2OS-R5 and U2OS-R5+FOXO3a and then monitored tumorigenesis for 30 days by measuring tumor volumes at 5-day inter-vals. Mice injected with MG63-R12+FOXO3a and U2OS-R5+FOXO3a cells showed significantly decreased tumor volumes (45% reduction by day 25) compared with mice injected with MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells (Figure 6D). These results suggested an important role for FOXO3a in the control of tumorigenesis in vivo, as well as tumor cell proliferation, sphere formation, and cell migration in vitro.

Discussion

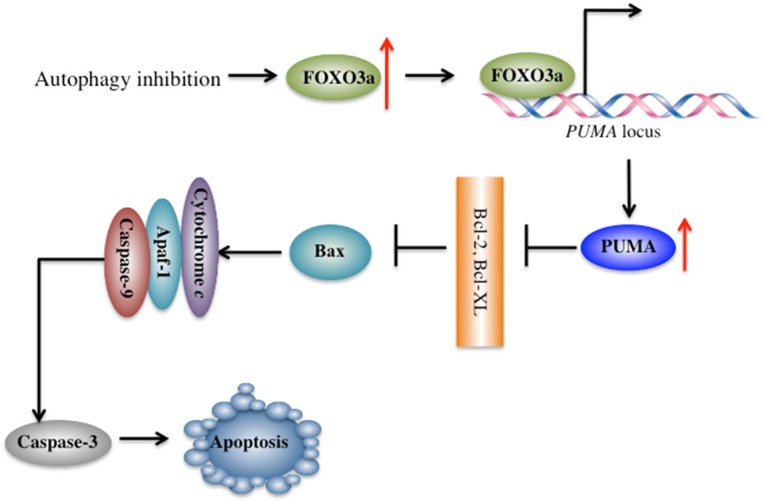

It is well known that autophagy often inhibits apoptosis [2]. Although many regulators that function in both autophagy and apoptosis processes have been identified, the underlying molecular mechanism is still not fully understood [20-22]. In the present study, we discovered that cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma cells have increased autophagy status, which causes the degradation of FOXO3a. Interestingly, the inhibition of autophagy results in FOXO3a accumulation, which can specifically bind to the promoter region of PUMA and activate its expression. The activated PUMA inversely inhibits anti-apoptotic proteins, such as Bcl-2, causing the abolition of Bcl-2 inhibiting Bax. This eventually leads to the activation of Bax, which further activates the caspase cascades and causes apoptosis (Figure 7). In conclusion, our results provide evidence for a transcriptional mechanism that connects autophagy and apoptosis. More importantly, this crosslink provides a reasonable approach for many ongoing clinical trials that use chloroquine-based drugs to inhibit autophagy to enhance the ability of other cancer drugs to induce apoptosis.

Figure 7.

A schematic diagram of the crosslink between autophagy and apoptosis in human osteosarcoma cells. Inhibition of autophagy signaling results in the accumulation of FOXO3a, which specifically binds to the promoter of PUMA and activates its expression. Activated PUMA inversely inhibits anti-apoptotic proteins, such as Bcl-2, causing the abolition of Bcl-2-inhibiting Bax, eventually leading to the activation of Bax, which further activates the caspase cascades and causes apoptosis.

Osteosarcoma is a solid tumor that commonly occurs in children and adolescents. Chemotherapy is an important part of the treatment for most people with osteosarcoma [25]. The drugs used most often to treat osteosarcoma include methotrexate, doxorubicin, cisplatin, ifosfamide, cyclophosphamide and epirubicin. Although these drugs exhibit good antitumor efficacy at the beginning of chemotherapy, osteosarcoma patients tend to show resistance to these drugs over time, and cancer cells are resurgent. To study the resistance of osteosarcoma cells to chemotherapeutic drugs, we treated two osteosarcoma cell lines, MG63 and U2OS, into medium containing cisplatin. Two obtained cisplatin-resistant sublines, MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5, exhibited higher levels of autophagy but lower levels of apoptosis after treatment with cisplatin (Figure 1C and 1D). These phenomena suggest that we may find some molecules that control the crosslink between autophagy and apoptosis in these cells. Then, we performed a microarray assay to analyze gene expression profiles in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells and sought to identify some key regulators. Fortunately, we found that the transcription factor FOXO3a is significantly downregulated in these cisplatin-resistant cells (Figure 3A and 3B). Pharmacological treatments to inhibit or activate autophagy caused inverse effects on the FOXO3a protein level; thus, the inhibition of autophagy causes the accumulation of FOXO3a, while the activation of autophagy leads to FOXO3a degradation (Figure 3C and 3D). However, we did not illuminate the mechanism of FOXO3a downregulation in cisplatin-resistant cells. The current understanding of FOXO3a modification include phosphorylation and ubiquitination. FOXO3a can be phosphorylated by a number of kinases, such as AKT, IKK (IκB kinase), and ERK1 and 2 (extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2), on multiple sites, such as S249, S322 and S325 [27]. The phosphorylation FOXO3a by AKT promotes its association with an ubiquitin E3 ligase, which can polyubiquitinate FOXO3a, eventually causing its degradation [27,28]. In recent years, a number of microRNAs, such as miR-29a [29], miR-132 [30], miR-182 [31], miR-212 [30], and miR-622 [32], have been reported to directly target the 3’-untranslated region (UTR) of FOXO3a and negatively regulate its expression. Because of the complicated mechanism of FOXO3a expression regulation, we will investigate the underlying mechanism of FOXO3a downregulation in cisplatin-resistant cells in the future.

Our results indicate that osteosarcoma cells seem to require a certain level of FOXO3a. The overexpression of FOXO3a in normal MG63 and U2OS cells does not significantly increased cell sensitivity to cisplatin; however, its overexpression in MG63-R12 and U2OS-R5 cells significantly increased the sensitivity of cells to cisplatin (Figure 4C and 4D). Moreover, the overexpression of FOXO3a in cisplatin-resistant cells can significantly decreases cell proliferation, sphere formation, cell migration and in vivo tumor formation ability (Figure 6D and Supplementary Figure 2). These results clearly demonstrate that the FOXO3a level is important for the carcinogenicity of osteosarcoma cells. More importantly, these results provide a new strategy for osteosarcoma drug resistance treatment in the future.

We also demonstrated that FOXO3a was able to directly bind to the PUMA promoter and positively regulate its expression (Figure 5). The degradation of FOXO3a in cisplatin-resistant cells results in the downregulation of PUMA and the inhibition of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway. Based on these results, we revealed the underlying mechanism of the decreased apoptosis status in cisplatin-resistant cells. Importantly, we also established a new crosslink between autophagy and apoptosis, the activation of autophagy causes FOXO3a degradation, thereby resulting in the downregulation of PUMA and eventually leading to the inhibition of apoptosis signaling. This crosslink is not dependent on p53 because it is upstream of PUMA (Figure 6A-C). However, we did not examine if the overexpression or downregulation of p53 has any effect on the FOXO3a level and the sensitivity of MG63-R12 or U2OS-R5 cells to cisplatin. The overexpression or downregulation of p53 in cisplatin-resistant cells would affect PUMA expression; however, we do not know if there is a feedback regulation mechanism between PUMA and FOXO3a. We will investigate the effect of p53 levels on this crosslink in the future.

In summary, our results uncovered three major findings: (1) we identified FOXO3a is a key factor in the regulation of human osteosarcoma cell sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs; (2) we revealed FOXO3a is able to specifically bind to the PUMA promoter and positively regulate the downstream event of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway; and (3) we showed a new transcriptional mechanism that connects autophagy and autophagy.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by two grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81672203 and No. 81602354), and a grant from the Emerging Frontier Technology Research Program of Shanghai Shen-Kang Hospital Development Center (No. SHDC12015103).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Authors’ contribution

Z. C. and H. S. designed the research. K. J. and C. Z. performed the major parts of the experiments. B. Y., B. C., Z. L., C. H., and F. W. performed parts of the research. C. Z., K. J., Z. C and H. S. analysed the data, tested statistics, and coordinated the figures. Z. C. and H. S. wrote the article. C. Z. and K. J. revised the article.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Fuchs Y, Steller H. Programmed cell death in animal development and disease. Cell. 2011;147:742–758. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nikoletopoulou V, Markaki M, Palikaras K, Tavernarakis N. Crosstalk between apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:3448–3459. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Khattouti A, Selimovic D, Haikel Y, Hassan M. Crosstalk between apoptosis and autophagy: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies in cancer. J Cell Death. 2013;6:37–55. doi: 10.4137/JCD.S11034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glick D, Barth S, Macleod KF. Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol. 2010;221:3–12. doi: 10.1002/path.2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizushima N. Autophagy: process and function. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2861–2873. doi: 10.1101/gad.1599207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alers S, Loffler AS, Wesselborg S, Stork B. Role of AMPK-mTOR-Ulk1/2 in the regulation of autophagy: cross talk, shortcuts, and feedbacks. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:2–11. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06159-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung CH, Ro SH, Cao J, Otto NM, Kim DH. mTOR regulation of autophagy. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung CH, Jun CB, Ro SH, Kim YM, Otto NM, Cao J, Kundu M, Kim DH. ULK-Atg13-FIP200 complexes mediate mTOR signaling to the autophagy machinery. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1992–2003. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell RC, Tian Y, Yuan H, Park HW, Chang YY, Kim J, Kim H, Neufeld TP, Dillin A, Guan KL. ULK1 induces autophagy by phosphorylating Beclin-1 and activating VPS34 lipid kinase. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:741–750. doi: 10.1038/ncb2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakatogawa H. Two ubiquitin-like conjugation systems that mediate membrane formation during autophagy. Essays Biochem. 2013;55:39–50. doi: 10.1042/bse0550039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nath S, Dancourt J, Shteyn V, Puente G, Fong WM, Nag S, Bewersdorf J, Yamamoto A, Antonny B, Melia TJ. Lipidation of the LC3/GABARAP family of autophagy proteins relies on a membrane-curvature-sensing domain in Atg3. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:415–424. doi: 10.1038/ncb2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong RS. Apoptosis in cancer: from pathogenesis to treatment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2011;30:87. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-30-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen X, Duan N, Zhang C, Zhang W. Survivin and tumorigenesis: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. J Cancer. 2016;7:314–323. doi: 10.7150/jca.13332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tait SW, Green DR. Mitochondria and cell death: outer membrane permeabilization and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:621–632. doi: 10.1038/nrm2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang F, Zhao X, Shen H, Zhang C. Molecular mechanisms of cell death in intervertebral disc degeneration (review) Int J Mol Med. 2016;37:1439–1448. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu H, Che X, Zheng Q, Wu A, Pan K, Shao A, Wu Q, Zhang J, Hong Y. Caspases: a molecular switch node in the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Int J Biol Sci. 2014;10:1072–1083. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.9719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell. 2010;140:313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zambrano J, Yeh ES. Autophagy and apoptotic crosstalk: mechanism of therapeutic resistance in HER2-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer (Auckl) 2016;10:13–23. doi: 10.4137/BCBCR.S32791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fimia GM, Corazzari M, Antonioli M, Piacentini M. Ambra1 at the crossroad between autophagy and cell death. Oncogene. 2013;32:3311–3318. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT, Tang D. The Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:571–580. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Indran IR, Tufo G, Pervaiz S, Brenner C. Recent advances in apoptosis, mitochondria and drug resistance in cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807:735–745. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wirawan E, Vanden Berghe T, Lippens S, Agostinis P, Vandenabeele P. Autophagy: for better or for worse. Cell Res. 2012;22:43–61. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X, Chen XG, Hu X, Song T, Ou X, Zhang C, Zhang W. MiR-34a and miR-203 inhibit survivin expression to control cell proliferation and survival in human osteosarcoma cells. J Cancer. 2016;7:1057–1065. doi: 10.7150/jca.15061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Z, Wang K, Hou C, Jiang K, Chen B, Chen J, Lao L, Qian L, Zhong G, Liu Z, Zhang C, Shen H. CRL4BDCAF11 E3 ligase targets p21 for degradation to control cell cycle progression in human osteosarcoma cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1175. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01344-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Kramer JL, Rowland JH, Stein KD, Alteri R, Jemal A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:271–289. doi: 10.3322/caac.21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang W, Duan N, Zhang Q, Song T, Li Z, Zhang C, Chen X, Wang K. DNA methylation mediated down-regulation of miR-370 regulates cell growth through activation of the Wnt/betacatenin signaling pathway in human osteosarcoma cells. Int J Biol Sci. 2017;13:561–573. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.19032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X, Hu S, Liu L. Phosphorylation and acetylation modifications of FOXO3a: independently or synergistically? Oncol Lett. 2017;13:2867–2872. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hedrick SM. The cunning little vixen: foxo and the cycle of life and death. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1057–1063. doi: 10.1038/ni.1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guerit D, Brondello JM, Chuchana P, Philipot D, Toupet K, Bony C, Jorgensen C, Noel D. FOXO3A regulation by miRNA-29a controls chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells and cartilage formation. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:1195–1205. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong HK, Veremeyko T, Patel N, Lemere CA, Walsh DM, Esau C, Vanderburg C, Krichevsky AM. De-repression of FOXO3a death axis by microRNA-132 and -212 causes neuronal apoptosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:3077–3092. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Segura MF, Hanniford D, Menendez S, Reavie L, Zou X, Alvarez-Diaz S, Zakrzewski J, Blochin E, Rose A, Bogunovic D, Polsky D, Wei J, Lee P, Belitskaya-Levy I, Bhardwaj N, Osman I, Hernando E. Aberrant miR-182 expression promotes melanoma metastasis by repressing FOXO3 and microphthalmia-associated transcription factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1814–1819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808263106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng CW, Chen PM, Hsieh YH, Weng CC, Chang CW, Yao CC, Hu LY, Wu PE, Shen CY. Foxo3a-mediated overexpression of microRNA-622 suppresses tumor metastasis by repressing hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in ERK-responsive lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:44222–44238. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.