Abstract

Pseudomonas fluorescens HC1-07, previously isolated from the phyllosphere of wheat grown in Hebei province, China, suppresses the soilborne disease of wheat take-all, caused by Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici. We report here that strain HC1-07 also suppresses Rhizoctonia root rot of wheat caused by Rhizoctonia solani AG-8. Strain HC1-07 produced a cyclic lipopeptide (CLP) with a molecular weight of 1,126.42 based on analysis by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Extracted CLP inhibited the growth of G. graminis var. tritici and R. solani in vitro. To determine the role of this CLP in biological control, plasposon mutagenesis was used to generate two nonproducing mutants, HC1-07viscB and HC1-07prtR2. Analysis of regions flanking plasposon insertions in HC1-07prtR2 and HC1-07viscB revealed that the inactivated genes were similar to prtR and viscB, respectively, of the well-described biocontrol strain P. fluorescens SBW25 that produces the CLP viscosin. Both genes in HC1-07 were required for the production of the viscosin-like CLP. The two mutants were less inhibitory to G. graminis var. tritici and R. solani in vitro and reduced in ability to suppress take-all. HC1-07viscB but not HC-07prtR2 was reduced in ability to suppress Rhizoctonia root rot. In addition to CLP production, prtR also played a role in protease production.

Additional keyword: biosurfactant

Take-all and Rhizoctonia root rot, caused by the soilborne necrotrophic fungal pathogens Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici and Rhizoctonia solani AG-8, respectively, cause severe damage to irrigated and dryland wheat and barley (6,48,49) in the Inland Pacific Northwest (PNW) of the United States. Take-all is considered one of the most important root diseases of wheat in the United States and worldwide and Rhizoctonia root rot is a severe problem in Australian cereal production; however, surprisingly, in the United States, root rot caused by R. solani AG-8 seems to be confined to the PNW. The incidence and severity of Rhizoctonia root rot is greatly exacerbated by reduced tillage, and this disease is the primary cause for the slow adoption of no-till (direct seeding), which is needed to reduce soil erosion in the PNW. Because of the lack of genetic resistance and the fact that fungicides are effective only during the seedling phase of these diseases, biological control by either introduced or indigenous agents and sustainable management practices represent the best options for long-term control (6,47,48,61,62). A disease decline phenomenon resulting in soils suppressive to either take-all (62,63) or Rhizoctonia root rot (36,54) has been described and many growers have utilized this highly sustainable natural form of biocontrol to manage these diseases. For example, Cook (6) reported that 0.8 million ha of PNW farmland are now cropped continuously or nearly so to rotations of spring wheat, spring barley, and winter wheat, and these crops suffer little damage from take-all owing to take-all decline (TAD) (6). Several promising biocontrol agents capable of suppressing take-all and Rhizoctonia root rot have been described and tested in the PNW and elsewhere. In particular, antibiotic-producing strains of gram-positive Bacillus spp. and gram-negative Pseudomonas spp. have proved to be effective as seed treatments in controlling G. graminis var. tritici or R. solani AG-8 under field conditions in the PNW (7,28,51,61).

Several groups of antibiotics are known to mediate the suppression of fungal phytopathogens by fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. (20,21,35), and antibiotics of special interest have included phenazines (37,38,58), pyoluteorin (20,25), pyrrolnitrin (20,24), and 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol (40,62), as well as biosurfactants like cyclic lipopeptides (CLPs) and rhamnolipids (27,45,52, 53,57). CLPs are versatile molecules with antimicrobial, cytotoxic, and surfactant properties produced by many different bacterial genera, including plant-associated Pseudomonas spp. (8,52). The potential of CLPs produced by Pseudomonas spp. to suppress diverse phytopathogens is documented in several different studies. For example, Tran et al. (59) demonstrated that the CLP massetolide A from Pseudomonas fluorescens SS101 played an important role in suppression of Phytophthora infestans, whereas viscosin contributed to the control of broccoli head rot by Pseudomonas fluorescens PfA7B (4). The CLP viscosin-amide produced by Pseudomonas sp. DR54 triggered the encystment of Pythium zoospores and reduced the mycelial growth of R. solani and Pythium ultimum (43). Amphisin played an important role in the surface motility of Pseudomonas sp. strain DSS73, allowing efficient containment of root-infecting plant-pathogenic fungi (44,45). Lipodepsipeptides produced by the pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae mediate the antagonism of this organism towards several phytopathogenic fungi (19). van den Broek et al. (60) reported that a lipopeptide was likely involved in the suppression of take-all of wheat by Pseudomonas sp. PCL1171. Finally, CLPs produced by Pseudomonas sp. CMR12a acted synergistically with phenazines in the control of Pythium and Rhizoctonia spp. on bean (9,50).

The biosynthesis and regulation of CLPs in Pseudomonas spp. has been well studied (8,52), with biosynthesis governed by nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) encoded by large gene clusters and composed of modules, one for each amino acid incorporated in the oligopeptide. Each module consists of several conserved domains, responsible for recognition, activation, transport, and binding of the amino acid to the peptide chain. A special thioesterase domain in the last module coordinates cyclization and release of the peptide product (8,18,52). In addition, many studies have focused on the genetic regulation of CLP production in pseudomonads. The well-known GacS/GacA two-component regulatory system appears to serve as a master switch for CLP production as it does for other secondary metabolites (10,16). Furthermore, acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing is involved in the regulation of some of the CLPs produced by Pseudomonas spp. (10,17). LuxR type transcriptional regulator genes, such as salA and syrG, were also found to play a role in CLP biosynthesis regulation (3,12,15). DnaK, a member of the Hsp70 heat-shock protein family, is involved in regulation of CLP synthesis in P. putida (16).

This study focused on the biocontrol agent P. fluorescens strain HC1-07, isolated from the phyllosphere of wheat grown in a field in Hebei province. In this region of China, there is a long history of cereal production; take-all is a chronic problem and little is known about the communities of wheat-associated, disease-suppressive bacteria (64). Strain HC1-07 was selected for further study because it was representative of one of the morphotypes of fluorescent pseudomonads isolated from wheat. This strain suppressed take-all of wheat caused by isolates of G. graminis var. tritici from both China and the PNW of the United States (64).

This study was part of an ongoing collaboration to select and develop biocontrol agents for use in Chinese agriculture, identify mechanisms of action, and determine the relatedness of the Chinese agents to others worldwide. Our specific aim was to determine the role of CLPs in the suppression G. graminis var. tritici and R. solani AG-8 by strain HC1-07. A CLP produced by strain HC1-07 was isolated and identified as a viscosin-like compound and two genes, viscB and prtR, involved in the CLP production were identified by random plasposon mutagenesis. We characterized the two CLP-deficient mutants and showed them to be less effective at controlling take-all compared with the wild-type strain; however, only the mutant disrupted in viscB was less suppressive of Rhizoctonia root rot.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms, media, and culture conditions

Bacteria and fungi used in this study are listed in Table 1. A spontaneous rifampicin-resistant derivative of P. fluorescens HC1-07 (64) with growth characteristics similar to those of the wild-type strain was used throughout this study. P. fluorescens and Escherichia coli were routinely cultured in King’s medium B (KMB) agar and broth (29) and Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (1), respectively. When needed, antibiotics were supplemented in the following concentrations: chloramphenicol (13 μg ml−1), tetracycline (25 μg ml−1), ampicillin (40 μg ml−1), cycloheximide (100 μg ml−1), and rifampicin (100 μg ml−1) (Table 1). Bacteria were stored at −80°C in LB broth supplemented with 40% (vol/vol) glycerol.

TABLE 1.

Bacteria and plasmids used in this study

| Organism, strain, or plasmid | Genotype, characteristicsz | Source/reference |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas fluorescens HC1-07 | CLP+ | 64 |

| HC1-07rif | Rifr CLP+ | This study |

| HC1-07viscB | Rifr viscB::TnMod CLP− | This study |

| HC1-07viscB-1 | Rifr CLP+ complemented mutant; viscB+ | This study |

| HC1-07prtR2 | Rifr prtR::TnMod CLP− | This study |

| HC1-07prtR2-1 | Rifr CLP+ complemented mutant; prtR2+ | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| S17-1(λpir) | thi pro hsdR hsdM recA rpsL RP4-2 Tetr::Mu Kanr::Tn7 λpir | Laboratory collection |

| DH5α | F− endAl hsdR17 supE44 thi-l gyrA96 relAl ΔargF-lacZYA U169 Φ80d lacZΔM15 λ− | Laboratory collection |

| Plasmids | ||

| p TnMod-OTc′ | TnMod; oriR; Tcr | 13 |

| pEX18Gm | Gene replacement vector; Gmr oriT sacB | Laboratory collection |

CLP = cyclic lipopeptide; Rifr, Tetr, Kanr, Tcr, and Gmr = resistant to rifampicin, tetracycline, kanamycin, tetracyline, and gentamicin, respectively.

G. graminis var. tritici isolates LD5, ARS-A1, and R3-111a-1 (32) and R. solani AG-8 isolate C-1 (26) were grown on one-fifth-strength potato dextrose agar (1/5 PDA) prepared from either fresh potato and adjusted to pH 6.5 as described by Yang et al. (64) or commercial potato dextrose broth (PDB) (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD). To prepare homemade PDA, diced potato tubers (200 g) were cooked in water in a microwave for 15 min and the resultant broth was strained and brought to 1 liter, supplemented with dextrose (20 g) and agar (15 g), and then autoclaved (64). All fungi were stored at 4°C on 1/5 PDA made from fresh potato and amended with rifampicin (100 μg ml−1) (31).

Generation of CLP-deficient mutants by transposon mutagenesis

CLP-deficient mutants of HC1-07rif were generated by subjecting the strain to mutagenesis with plasposon TnMod-OTc′ (13). The plasposon was delivered into HC1-07rif using biparental matings with E. coli S17-1 (λpir). The transposants were selected on LB amended with tetracycline and rifampicin, then screened for the loss of biosurfactant production by the drop-collapse assay (14), which measures the ability of a bacterial metabolite to reduce surface tension of a liquid spotted on a piece of Parafilm.

The number of TnMod-OTc′ copies in genomes of the biosurfactant-deficient mutants was analyzed by Southern blot hybridization. Briefly, genomic DNA was isolated using a GenElute Bacterial Genomic DNA kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted DNA was dissolved in 100 μl of sterile deionized water and stored at −20°C. Genomic DNA of the mutants was digested to completion with endonucleases EcoRV and PstI. The DNA fragments were separated on a 1% agarose gel and transferred onto a Hybond N nylon membrane (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) using standard techniques (1). The hybridization probe contained a 515-bp fragment of the tetracycline resistance gene and was obtained by amplification of p TnMod-OTc′ with primers Tet_UP and Tet_LOW (38). The probe was labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) using DIG High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany).

The hybridization conditions included prehybridization (1.5 h at 65°C) and hybridization (12 h at 65°C) steps followed by stringency washes (twice each for 5 min with 2× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate] and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS] at room temperature, and twice each for 30 min with 0.1× SSC and 0.1% SDS at 65°C). The hybridized DIG-labeled probe was immunodetected according to the protocol provided by Roche.

To characterize regions flanking plasposon insertion sites, 1 μg of total genomic DNA was digested with EcoRI (does not cut within TnMod-OTc′) and the resultant fragments were self-ligated under conditions favorable for intramolecular reactions. The ligation mixture (2 μl) was transformed into E. coli DH5α by electroporation and clones containing the resultant TnMod-OTc′-based plasmids were selected by plating on LB amended with tetracycline. Regions of the HC1-07 genome flanking the TnMod-OTc′ insertion sites were sequenced using the plasposon-based oligonucleotide primers Ori (5′-GGCCTTTTGCTCACATGT-3′) and Tet (5′-TCAATTCTTGCGGAGAAC-3′).

Genetic complementation of CLP-deficient mutants

The CLP-deficient mutants HC1-07viscB and HC1-07prtR2 were complemented as follows. The 1.0-kb fragment of viscB corresponding to the TnMod-OTc′ integration site in HC1-07viscB was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with primers viscB1 (5′-GGAGCAACTGGTACAGGCGT-3′) and viscB2 (5′-GCACTTCGTAGGTAGTGGCGT-3′) using DNA of HC1-07 as a template. Similarly, the 1.0-kb fragment of prtR that corresponds to the plasposon integration site in HC1-07prtR2 was amplified by PCR with primers PrtR1 (5′-AGCTCAACACCGAGCAGC-3′) and PrtR2 (5′-TATCGGCAGCCAGGTGTT-3′), again using DNA of HC1-07 as a template. Both amplicons were cloned into pEX18Gm and the resultant plasmids were single-pass sequenced to ensure the absence of mutations. The plasmids were mobilized into HC1-07viscB or HC1-07prtR2, respectively, using biparental matings with E. coli S17-1 (λpir). Single crossover events were recovered on LB medium supplemented with gentamicin, and several gentamicin-resistant colonies were streaked on LB amended with 5% sucrose to select for double crossovers. The reversion to wild-type viscB and prtR alleles and the loss of the pEX18Gm backbone were confirmed by PCR with primer sets viscB1/viscB2, PrtR1/PrtR2, and GM_UP/GM_LOW (38). The complemented mutants were also assayed by the drop collapse assay for the gain of function to produce CLP.

Phenotypic profiling

Swimming and swarming motility were visualized by spot-inoculating bacteria on standard succinate medium (12) supplemented with 0.25% (wt/vol) (swimming motility assays) and 0.6% (wt/vol) (swarming motility assays) of agar. The inoculated plates were incubated overnight at 28°C. Biofilm formation was assessed in untreated polystyrene flat-bottom 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, NC) prefilled with 200 μl of M63 medium, as described by O’Toole and Kolter (46) and Dubern et al. (17). Exoprotease production was assessed according to Lawrence et al. (34) by inoculating 20 μl of a 24-hold bacterial culture in wells cut in 2.5% skim milk agar using a 4-mm cork borer. The inoculated plates were incubated for 48 h at 28°C and the diameter of the halo was measured. The production of siderophores was determined by measuring orange haloes after 2 days of growth at 28°C on CAS (chrome azurol S) agar (54). All assays were repeated twice, with three replicates per strain.

In vitro inhibition of fungal pathogens by strain HC1-07 and its isogenic derivatives

The capacity of HC1-07 and its isogenic mutant and recombinant derivatives to inhibit the growth of G. graminis var. tritici isolates LD5, ARS-A1, and R3-111a-1 and R. solani AG-8 isolate C-1 was tested on PDA made from fresh potato, as described by Yang et al. (64). Aliquots (5 μl) from overnight cultures of each strain grown in KMB broth were spotted 1 cm from the edge of a Petri dish containing homemade PDA and allowed to soak into the agar. A 0.5-cm plug from the leading edge of a 7-day-old 1/5 PDA culture of G. graminis var. tritici or 5-day-old culture of R. solani was placed in the center of the plate. The inoculated plates were incubated at 24°C and scored after 5 or 7 days by measuring the distance between the edges of the bacterial colony and the fungal mycelium. Each plate consisted of three isolates and a control that was not inoculated. All assays were repeated twice and each isolate was replicated three times. Inhibition was expressed relative to a noninoculated control.

Isolation and characterization of CLP

To extract the CLP, strain HC1-07 and its mutant derivatives were grown on KMB agar for 48 h at 28°C. The bacterial cells were scraped from the agar surface and washed twice in 20 ml of sterile deionized water. The supernatant was passed through a membrane filter (0.22-μm pore size), acidified to pH 2.0 with 9% HCl, and kept on ice for 1 h. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation (30 min at 6,000 rpm and 4°C) and washed twice with sterile deionized water (pH 2.0) (14). The precipitate was resuspended in 20 ml of sterile deionized water (pH 8.0) and lyophilized (Supermodul Yo-220; Thermo Savant, NY). The lyophilized extract was stored at −20°C. The lyophilized sample was analyzed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) by the State Key Laboratory of Coordination Chemistry, Nanjing University, essentially as described by Hong et al. (23). Briefly, an aliquot of the biosurfactant sample was dissolved in methanol to obtain a stock solution of 1 mg ml−1. Freshly prepared working solutions were made by diluting the stock solution with methanol to 10 or 15 μg ml−1. ESI mass spectra were recorded using a Finnigan MAT LCQ ion-trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Finnigan, San Jose, CA) in the positive ionization mode. Samples were injected at a flow rate of 2 μl min−1. Source voltage and capillary voltage were 5.0 kV and 17 V in positive ion mode. Capillary temperature and sheath gas (N2) flow were set at 290 and 12 arbitrary units, respectively, in both scan modes. Data were acquired in positive MS total ion scan mode (mass scan range of m/z 200 to 2,000).

Effect of CLPs on the growth of G. graminis var. tritici and R. solani AG-8

The effect of the CLP on growth of the G. graminis var. tritici isolates and R. solani AG-8 C-1 was examined as follows. The CLP was extracted from strain HC1-07 as described above. A 5-mm-diameter plug was excised from the margin of a 7-day-old 1/5 PDA culture of G. graminis var. tritici or 5-day-old culture of R. solani AG-8 and placed in the center of a Petri plate containing 1/5 PDA amended with the CLP at 0, 10, or 100 μg ml−1. The inoculated plates were incubated at room temperature and radial hyphal growth was measured at 5 days for R. solani AG-8 or 7 days for G. graminis var. tritici. Three replicate plates per concentration were included in the experiment and the entire experiment was repeated twice.

Treatment of wheat seed with bacteria

For greenhouse biocontrol or root colonization studies in the field, wheat seed (‘Penawawa’ or ‘Louise’) was treated with bacteria, as described by Yang et al. (64). Briefly, KMB plates were spread inoculated with the test bacterium and incubated for 48 h at room temperature. A 1% methyl cellulose solution (4 ml) (M-6385; Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the plate and the bacteria were scraped into a test tube, shaken for 30 s, and then mixed with 5.3 g of wheat seed. Treated seed were dried for 2 h under a stream of sterile air. The final density of bacteria was ≈107 CFU seed−1. For field studies, larger amounts of seed were treated using the same proportions.

Preparation of oat-kernel inoculum

Inoculum of G. graminis var. tritici and R. solani AG-8 was prepared essentially as described by Kwak et al. (31). Briefly, 250 ml of untreated whole oat grains plus 350 ml of water were combined in a 1-liter flask and autoclaved for 90 min on each of two successive days. Sterile oat grains were inoculated with agar disks of G. graminis var. tritici isolate LD5 or R. solani AG-8 isolate C-1. After 3 to 4 weeks of growth at room temperature, the contents of each jar were air dried and stored at 4°C.

Biological control assays

A tube assay previously described by Yang et al. (64) was used to determine the biocontrol activity of bacteria against take-all or Rhizoctonia root rot. Briefly, plastic tubes (2.5 cm in diameter and 16.5 cm long) were supported in a hanging position in racks (200 cones rack−1). The hole in the bottom of each tube was plugged with a cotton ball and the tube was then filled with a 6.5-cm-thick column of sterile vermiculite followed by air-dried and sieved Quincy virgin soil (Shano sandy loam) (10 g). For some experiments, the soil was first pasteurized (60°C for 30 min) in order to reduce the interference from other soilborne pathogens. G. graminis var. tritici or R. solani colonized oat-kernel inoculum was pulverized in a Waring Blender and sieved into fractions of known particle sizes. The fraction of 0.25 to 0.5 mm was added to the soil at 0.7 and 1.0% (wt/wt) for G. graminis var. tritici and R. solani, respectively. Three bacteria-treated wheat seed were placed on the soil surface and covered with a 1.5-cm-thick topping of vermiculite. Each tube received 10 ml of water. The rack of tubes was incubated at 15 to 18°C in a 12-h cycle of light and darkness and, for the first 4 days, was covered with plastic. After the plastic was removed, each cone received 10 ml of water two times a week and diluted (1:3 [vol/vol]) Hoagland’s solution (macroelements only) once a week. All treatments were replicated five times and arranged in a randomized complete block design. After 3 to 4 weeks, plants were removed from the tubes, the roots were washed free of soil, and plants were evaluated for disease severity on a scale of 0 to 8, as previously described (26,51), where 0 = no disease evident and 8 = plants dead or nearly so. All experiments were repeated at least twice with similar results.

Rhizosphere colonization assays

Bacterial strains were tested under both controlled and field conditions for ability to colonize roots of wheat. For assays under controlled conditions, bacteria (strains HC1-07rif, HC1-07viscB, HC1-07prtR2, HC1-07viscB-1, and HC1-07prtR2-1) were prepared and applied individually to Quincy virgin soil in a 1% methylcellulose suspension, as previously described (33,39), to obtain 104 CFU g−1 of soil. The actual density of each strain introduced into the soil was determined by assaying 0.5 g of inoculated soil, as described below. Control soils consisted of soil amended only with a 1% methylcellulose suspension. Each treatment was replicated six times with a single pot serving as a replicate. Spring wheat (Penawawa) seed were pregerminated in the dark on moistened sterile filter paper in petri dishes (24 h) and were sown (6 per pot) in square pots (height, 6.5 cm; width, 7 cm) containing 200 g of Quincy virgin soil (33) inoculated with one of the bacterial strains. Control treatments consisted of soil amended with a 1% methylcellulose suspension. Plants were grown for three successive cycles in a controlled environment chamber at 15 to 18°C with 12-h photoperiod. After 2 weeks of growth (one cycle), population densities of bacteria were determined essentially as described by Mavrodi et al. (39). Briefly, for each replicate, the roots plus adhering rhizosphere soil from three individual plants were excised and assayed by first vortexing in 10 or 20 ml of sterile water (depending on the amount of roots) followed by sonication in a water bath. Each plant was processed separately. Population densities of the introduced strains were monitored by the modified dilution endpoint method (42,64). Briefly, to detect the introduced strains, the soil suspensions were serially diluted in wells of 96-well microtiter plates containing sterile water (200 μl) and these dilutions were transferred to plates containing 1/3× KMB broth supplemented with rifampicin, cycloheximide, ampicillin, and chloramphenicol (1/3× KMB+++Rif). Population densities of total culturable heterotrophic aerobic bacteria were determined by performing the same assay in 1/10× tryptic soy broth supplemented with only cycloheximide (1/10× TSB+). Plates with 1/3× KMB+++Rif and 1/10× TSB+ were incubated for 72 and 48 h, respectively, at room temperature and an optical density at 600 nm ≥ 0.1, measured with a microplate reader, was scored as positive for growth.

A field test of the ability of strain HC1-07rif to colonize the rhizosphere of the spring wheat (Louise) grown without irrigation at the Washington State University Plant Pathology Research Farm, Pullman was conducted in 2010. As previously described (64), the plot was cultivated in the spring and fertilized with 89-25-20-10 (N-P-S-Cl), which was applied as a dry formulation and incorporated to a depth of 10 to 15 cm. Seed furrows (40.6 cm apart) were opened mechanically to a depth of 6 to 8 cm and seed were hand sown and covered with ≈3 cm of soil. Treatments included strain HC1-07rif, applied at ≈107 CFU seed−1 as described above, and nontreated seed as a control. Treatments were part of a larger experiment and arranged in a randomized complete block design.

Each treatment consisted of four 2.13-m-long rows and was replicated six times. Every 3 weeks, plants were sampled from three locations in a replicate by digging them with a shovel to a depth of ≈20 cm, and excess soil was removed from the roots by gentle shaking. Plants from each replicate were placed in a new plastic bag, transferred to the laboratory, and immediately processed. For each replicate, the roots plus adhering rhizosphere soil from three individual plants were processed separately. The population size of introduced strain HC1-07rif and the indigenous culturable heterotrophic aerobic bacteria in the rhizosphere was detected with the dilution end-point assay, as described above.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by using appropriate parametric and nonparametric procedures with the STATISTIX 8.0 software (Analytical Software, St. Paul, MN). All population data were converted to log CFU per gram (fresh weight) of root. Differences in population densities among treatments were determined by standard analysis of variance, and mean comparisons among treatments were performed by using Fisher’s protected least-significant-difference test (P = 0.05) or the Kruskal-Wallis all-pairwise comparison test (P = 0.05). Data from phenotypic assays were compared by using a two-sample t test or the Wilcoxon rank sum test (P = 0.05).

Accession numbers

The nucleotide sequences of viscB and prtR genes of P. fluorescens HC1-07 were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AFN27384.1 and AFN27386.1, respectively.

RESULTS

Isolation and characterization of biosurfactants produced by P. fluorescens HC1-07

Extraction of CLP from the culture supernatant of P. fluorescens HC1-07 yielded a white precipitate (≈90% pure) (data not shown) that was analyzed by ESI-MS. Results of the analysis revealed a major peak in the mass spectrum at m/z 1,125.42 [M+H]−, which closely matched the molecular weight of the biosurfactants viscosin, massetolide F, or massetolide L (produced by some strains of P. fluorescens) (Supplemental Figure 1) (10). Amino acid analysis of the CLP (conducted by the Washington State University Laboratory for Bioanalysis & Biotechnology, Pullman) narrowed the possibilities to massetolide F or viscosin (data not shown).

The CLP extracted from HC1-07 was tested for the capacity to inhibit hyphal growth of G. graminis var. tritici and R. solani. Addition of the CLP to growth media at concentrations of 10 and 100 μg ml−1 resulted in strong inhibition of both pathogens (Table 2; Supplemental Figure 2) but G. graminis var. tritici was more sensitive to the CLP than R. solani. The hyphal growth of G. graminis var. tritici was completely inhibited by the viscosin-like CLP at 100 μg ml−1, whereas the same amount of this CLP caused only 55% inhibition of R. solani (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Relative inhibition (%) of radial hyphal growth of Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici and R. solani pathogenic isolates cultured on one-fifth-strength potato dextrose agar (1/5 PDA) amended with cyclic lipopeptide (CLP) at the indicated concentrationz

| Pathogens | CLP concentration (μg/ml) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 0 | 10 | 100 | |

| G. tritici LD5 | 0 | 42.9 | 100.0 |

| G. tritici ARS-A1 | 0 | 50.0 | 100.0 |

| G. tritici R3-111a-1 | 0 | 35.0 | 100.0 |

| R. solani AG-8 | 0 | 10.0 | 55.0 |

Data represent the mean from three replicate plates. Reduction of radial hyphal growth of the pathogens on 1/5 PDA amended with indicated concentration of CLP compared with that on the control plate (no CLP amended).

Plasposon mutagenesis and characterization of CLP-deficient mutants

To clone genes involved in the production of the CLP, P. fluorescens HC1-07 was subjected to mutagenesis with the TnMod-OTc′ plasposon. As a result, in total, 390 transformants were obtained. Two of these, HC1-07viscB and HC1-07prtR2, failed to produce CLP, which was evident from the absence of foam formation after vigorous shaking and inability to lower the surface tension of water during the collapsed drop assay (Fig. 1). Southern hybridization showed that each of the two mutants contained single-transposon integration events. The mutants were further tested for the ability to swim and swarm on semisolid medium, and to produce siderophores, exoprotease, and biofilm. Results of the testing revealed that HC1-07viscB and HC1-07prtR2 were deficient in swimming and swarming motility (Table 3; Supplemental Figure 3A and B). In addition to that, HC1-07prtR2 lost the ability to secrete exoprotease at 23 and 29°C (Table 3; Supplemental Figure 3C), while HC1-07viscB retained the wild-type levels of exoprotease production. The production of siderophores in both mutants remained unaffected and similar to that in HC1-07 (Table 3; Supplemental Figure 3D). HC1-07viscB and HC1-07prtR2 were reduced in ability to form biofilms compared with the wild-type strain (Table 3; Fig. 1B). The genetic complementation of mutants with the corresponding wild-type DNA fragments restored the surface motility and production of exoprotease to the wild-type levels and partially restored biofilm formation (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of biosurfactant production and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens HC1-07rif and its cyclic lipopeptide-deficient mutants and complemented mutant derivatives. A, Drop collapse assay with cultures of the wild-type strain HC1-07rif, two mutants (HC1-07viscB and HC1-07prtR2), and two complemented mutants (HC1-07viscB-1 and HC1-07prtR2-1). Bacterial cells grown for 2 days at 28°C were resuspended in sterile water, and 20-μl droplets were spotted on Parafilm. A flat droplet is indicative of viscosin production. B, Biofilm formation by strain HC1-07 and its mutants in polystyrene microtiter plates. Cells firmly attached to the walls of the wells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet.

TABLE 3.

Phenotypes of HC1-07, cyclic lipopeptide (CLP)-deficient mutants, and complemented strainsx

| Strain | CLP | Production ofy | Biofilm formationz | Swarming motility | Swimming motility | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Exoprotease (cm) | Siderophores (cm) | |||||

| HC1-07rif | + | 0.97 A | 1.12 A | 0.35 A | + | + |

| HC1-07 viscB | − | 0.93 A | 1.37 A | 0.05 B | − | − |

| HC1-07 viscB-1 | + | 0.96 A | 1.26 A | 0.20 AB | + | + |

| HC1-07 prtR2 | − | ND | 1.13 A | 0.06 B | − | − |

| HC1-07 prtR2-1 | + | 0.96 A | 1.18 A | 0.21 AB | + | + |

Means in the same column followed by the same letter are not significantly different at P = 0.05 according to the Kruskal-Wallis all-pairwise comparison test. ND = no halo detected. HC1-07prtR2 was not included in the analysis of halo diameter.

Halo diameter.

Absorbance at 600 nm.

Identification of genes affected by the plasposon insertions

In order to identify genes interrupted by TnMod-OTc′ in strains HC1-07viscB and HC1-07prtR2, we recovered and sequenced DNA regions flanking the plasposon insertions. Comparison of the resultant sequences against the nonredundant GenBank dataset revealed that, in HC1-07viscB, the plasposon insertion disrupted a gene with strong similarity (90% identity at the amino acid level to NRPS; blastp E-value 0.0) to viscB, a gene involved in the production of the biosurfactant viscosin in P. fluorescens SWB25, and closely related to NRPSs from other Pseudomonas spp. (Table 4). Collectively, this finding, along with data generated by MS and amino acid analyses, indicated that the CLP was similar to viscosin. In HC1-07prtR2, the plasposon insertion disrupted a gene encoding a transmembrane regulator with strong similarity (94% identity at the amino acid level; blastp E-value 5e-148) to PrtR of P. fluorescens SWB25. Results of blast searches revealed that homologous genes were also present in other fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. (Table 5).

TABLE 4.

Comparison of the putative nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) ViscB of Pseudomonas fluorescens HC1-07 to similar protein sequences from other Pseudomonas spp.

| Organism | Gene function | NCBI accession numberz | Blastp E-value | Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. fluorescens SBW25 | Putative NRPS | YP002872142.1 | 0.0 | 90 |

| P. synxantha BG33R | NRPS MassC | ZP10142895.1 | 0.0 | 81 |

| Pseudomonas sp. Ag1 | Putative NRPS | ZP10143315.1 | 0.0 | 79 |

| P. fluorescens SS101 | Putative NRPS | ABH06369.2 | 0.0 | 79 |

National Center for Biotechnology Information.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of the regulatory protein PrtR of Pseudomonas fluorescens HC1-07 to similar protein sequences from other Pseudomonas spp.

| Species | Strain | Gene function | NCBI accession numberz | Blastp E-value | Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. fluorescens | SBW25 | Putative transmembrane regulator | YP002873451.1 | 5e-148 | 94 |

| P. fluorescens | LS107d2 | Transmembrane regulator | AAF81075.1 | 2e-143 | 89 |

| P. extremaunstralis | 14.3b | Transcriptional regulator | ZP101437425.1 | 2e-142 | 89 |

| P. fluorescens | SS101 | Transmembrane regulator | EIK58907.1 | 3e-136 | 85 |

National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Impact of viscB and prtR mutations on rhizosphere colonization of HC1-07

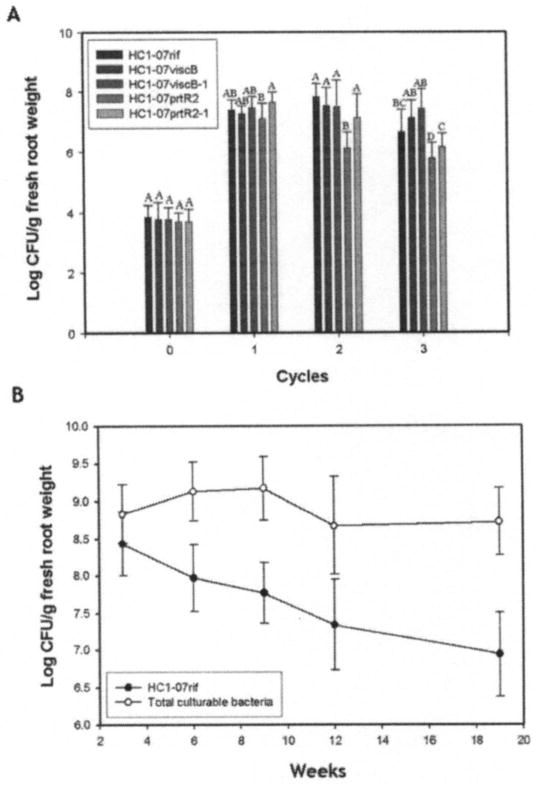

The impact of viscB and prtR mutations on the ability of HC1-07 to colonize and persist in the rhizosphere of wheat was tested under controlled conditions in a growth chamber. In the wheat cycling experiment, HC1-07rif, mutants, and complemented mutants were introduced individually into Quincy virgin soil and population sizes of each strain were determined in the wheat rhizosphere after each 2-week-long growth cycle of wheat. Of the two tested mutants, only HC1-07prtR2 was mildly but significantly impaired in the ability to persist in the wheat rhizosphere (Fig. 2A). In cycle 2, the population size of HC1-07prtR2 was ≈1 log unit lower than that of the wild-type parent and significantly less than the other strains. Complementation of the prtR mutation restored plant colonization to the wild-type levels. In cycle 3, the same trend was seen, and the population size of mutant HC1-07prtR2 was significantly lower than that of the wild type and the complemented strain HC1-07prtR2-1.

Fig. 2.

A, Root colonization by HC1-07rif, cyclic lipopeptide-deficient mutants HC1-07viscB and HC1-07prtR2, and complemented mutants HC1-07viscB-1 and HC1-07prtR2-1 in a wheat cycling experiment conducted under controlled conditions in a growth chamber. Bacteria were introduced into the soil to give approximately 104 CFU g soil−1. Cycle 0 shows population sizes of each strain in the soil at the time of planting. Each cycle of wheat growth lasted 2 weeks, at which time the wheat was harvested and another cycle of wheat was then planted. Bars indicate means and error bars indicate standard deviations. The same letter above bars for the same cycle indicates that the means are not significantly different (P = 0.05) according to the Fisher’s protected least-significant-difference test (unless indicated otherwise). B, Root colonization of spring wheat (‘Louise’) in the field at Pullman, WA by strain HC1-07rif. Seed were treated with HC1-07rif at approximately 106 CFU/seed, population sizes were determined every 3 weeks after planting, and the last sample was taken at week 19. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Because HC1-07 was originally isolated from the phyllosphere, we also determined its ability to colonize and survive in the rhizosphere of wheat in the field. Under field conditions, the population sizes of HC1-07 on the roots at the first sampling time (3 weeks after planting) were 108 CFU g−1 fresh root weight and declined thereafter to ≈107 CFU g−1 fresh root weight over a period of 16 weeks (Fig. 2B).

Impact of viscB and prtR mutations on biocontrol of take-all and Rhizoctonia root rot

The capacity of P. fluorescens HC1-07 and its isogenic mutants and complemented mutant derivatives to inhibit hyphal growth of G. graminis var. tritici and R. solani was first assessed in vitro. The wild-type HC1-07 demonstrated strong inhibition of three isolates of G. graminis var. tritici and of R. solani AG-8 (Table 6; Supplemental Figure 4). In contrast, CLP-deficient mutants HC1-07viscB and HC1-07prtR2 were greatly reduced in ability to inhibit the growth of the pathogens, and complemented derivatives of both mutants regained the ability.

TABLE 6.

In vitro inhibition of Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici and Rhizoctonia solani by the wild-type HC1-07, cyclic lipopeptide-deficient mutants, and complemented mutant derivatives

| Treatment | Relative inhibition of radial hyphal growth (%)z | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| G. graminis var. tritici | R. solani | |||

|

| ||||

| LD5 | ARS-A1 | R3-111a-1 | ||

| HC1-07rif | 56.1 A | 56.3 A | 56.8 A | 46.1 B |

| HC1-07viscB | 15.3 B | 5.8 C | 12.5 C | 8.7 C |

| HC1-07viscB-1 | 50.1 A | 47.2 B | 49.9 AB | 54.8 A |

| HC1-07prtR2 | 10.1 B | 16.7 C | 8.1 C | 5.7 C |

| HC1-07prtR2-1 | 47.9 A | 53.3 AB | 44.9 B | 50.8 AB |

Data represent the mean from three replicate plates. Means in the same column followed by the same letter are not significantly different at P = 0.05 according to Fisher’s protected least significant difference test. Distance between the bacterial colony and the edge of the mycelium on one-fifth-strength potato dextrose agar compared with that on the control plate (not inoculated with bacteria).

The wild-type HC1-07, its CLP-deficient mutants HC1-07viscB and HC1-07prtR2, and complemented mutants were also tested for the ability to suppress G. graminis var. tritici and R. solani AG-8 under controlled conditions. Strain HC1-07 applied as a seed treatment provided significant suppression of take-all and Rhizoctonia root rot based on root disease ratings when compared with the nontreated controls in both raw and pasteurized soil (Table 7). When compared with the wild-type parent, the two CLP-deficient mutants provided significantly less suppression (P = 0.05) of take-all based on root disease ratings. However, the mutants did not lose all of their biocontrol activity. Genetically complemented mutants regained the ability to control take-all (Table 7) to the same level as the wild type. The results were similar when tests were done in both raw and pasteurized soil. In contrast, these strains responded differently against Rhizoctonia root rot. Mutant HC1-07viscB but not HC1-07prtR2 suppressed Rhizoctonia root rot significantly less than the wild type in raw and pasteurized soil (Table 7). Only in pasteurized soil did the genetically complemented strain HC1-07viscB-1 show fully restored biocontrol activity (Table 7). Thus, the viscosin-like CLP appeared to be a more important determinant of disease suppression against take-all than Rhizoctonia root rot.

TABLE 7.

Severity ratings of take-all and Rhizoctonia root rot disease in wheat inoculated with HC1-07 wild-type, cyclic lipopeptide-deficient mutants, and complemented mutants as seed treatments

| Treatmenty | Disease severity ratingz | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Take-all | Rhizoctonia root rot | |||

|

|

|

|||

| Pasteurized | Raw | Pasteurized | Raw | |

| HC1-07rif | 2.8 D | 3.2 C | 2.5 C | 2.4 C |

| HC1-07viscB | 3.5 C | 3.6 B | 3.3 B | 2.9 B |

| HC1-07viscB-1 | 3.1 D | 3.4 C | 2.6 C | 2.6 BC |

| HC1-07prtR2 | 3.9 B | 3.7 B | 2.8 C | 2.8 BC |

| HC1-07prtR2-1 | 3.0 D | 3.3 C | 2.6 C | 2.5 BC |

| CK+pathogen | 4.4 A | 3.9 A | 4.3 A | 4.3 A |

| CK+MC+pathogen | 4.1 AB | 4.1 A | 4.1 A | 4.2 A |

CK, a nontreated control; CK+MC, seed treated with methyl cellulose; bacteria were applied to the seed with methyl cellulose at a dose of 107 CFU seed−1.

Ratings represent the mean disease severity on 90 replicate plants on a scale of 0 to 8, where 0 = no disease detected and 8 = dead plants. Means in the same column followed by the same letter are not significantly different at P = 0.05 according to the Kruskal-Wallis all-pairwise comparison test.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated the involvement of a CLP from P. fluorescens stain HC1-07 in the biocontrol of take-all and Rhizoctonia root rot, two economically important diseases of wheat. Results of this work revealed that P. fluorescens HC1-07 produces a CLP with molecular structure similar to that of viscosin. Viscosin is a CLP that was first isolated from P. viscosa (30) and was later implicated as a key metabolite responsible for the ability of Pseudomonas spp. to control the brown blotch disease of mushrooms caused by P. tolaasii (56). Three lines of evidence suggested that the viscosin-like CLP is an important component of the biocontrol activity of strain HC1-07. First, the addition of CLP extracted from HC1-07 to the growth medium even at a concentration of 10 μg ml−1 inhibited the hyphal growth of both G. graminis var. tritici and R. solani AG-8. Second, both CLP-nonproducing mutants HC1-07viscB and HC1-07prtR2 were significantly less effective in biocontrol of take-all than HC1-07, and HC1-07viscB was reduced in activity against Rhizoctonia root rot. Finally, genetic complementation of the mutants HC1-07viscB and HC1-07prtR2 restored their biocontrol activity to wild-type levels. CLP production is only one mechanism of suppression in strain HC1-07 because the mutants still retained significant biocontrol activity compared with the nontreated controls. In addition, the viscosin-like CLP appears to be a much more important determinant of disease suppression against take-all than Rhizoctonia root rot because the mutant HC1-07prtR2 was not significantly different from the wild type in Rhizoctonia spp. control. This is not surprising given that both extracted CLP and HC1-07 showed greater inhibition of G. graminis var. tritici than R. solani in vitro. In addition, these two organisms belong to different classes of fungi (Ascomycetes and Basidiomycetes, respectively). Furthermore, it is also known that G. graminis var. tritici is especially sensitive to many different mechanisms of biocontrol compared with other soilborne fungi (63).

In order to identify genes involved in the production of the viscosin-like CLP in HC1-07, we subjected this strain to plasposon mutagenesis and characterized genetic loci affected in the two resultant CLP-deficient mutants. In the first mutant, HC1-07viscB, the mutation site was located in the gene similar to viscB of P. fluorescens SBW25, which encodes for ViscB, a NRPS. In SBW25 (from the phyllosphere of sugar beet in the United Kingdom), viscB is one of the three key genes (viscA, viscB, and viscC) in the synthesis of viscosin (11). In the second mutant, the mutation site was found in the gene prtR, which encodes a transmembrane regulator PrtR. prtR is translationally coupled to an upstream gene, prtI, which encodes an ECF (extracytoplasmic function) σ factor. PrtR was reported to be required for protease expression at 29 but not 23°C in Pseudomonas LS107d2 (5). We found that mutating the prtR gene also resulted in the loss of protease activity but at both 23 and 29°C; thus, protease production in the mutant HC1-07prtR was not related to the temperature. Interestingly, prtR in HC1-07 not only plays a role in protease production but also functions in regulation of the production of the viscosin-like CLP. De Bruijn and Raaijmakers (12) reported a similar phenomenon in P. fluorescens SS101, where the serine protease ClpP regulates the biosynthesis of the CLP massetolides, which are involved in swarming motility, biofilm formation, and antimicrobial activity.

CLP production is known to play an important role in surface motility and biofilm formation (11,52). Our soft agar assays showed that the mutants HC1-07viscB and HC1-07prtR2 were completely impaired in surface motility, a result also reported for the viscosin-deficient mutants of P. fluorescens SBW25 (11). In addition, microtiter plate assays showed that the two mutants produced significantly less biofilm than the wild-type HC1-07 and the complemented mutants. Different CLPs, including arthrofactin and putisolvin, have been reported to influence biofilm formation; however, the way that this occurs is still unclear but their impact on cell surface hydrophobicity may be important in this process. Hydrophobic interactions and surface-active compounds, such as CLPs, are thought to play a role in the adherence of cells to surfaces (53).

The function of CLPs in colonization and dispersal of bacteria in natural habitats is still emerging but apparently varies by plant species and ecological niche. Tran et al. (59) showed that the wild-type strain P. fluorescens SS101, when applied to tomato seed, was more effective in colonizing the root system of tomato seedlings than its massetolide-deficient mutant. Similarly, a viscosin-deficient mutant of P. fluorescens strain 5064 was unable to colonize the surface of intact broccoli florets (22). Surfactin and amphisin produced by B. subtilis strain 6031 and Pseudomonas sp. DSS73, respectively, were also shown to be important traits in the colonization of Arabidopsis roots and sugar beet seed (2,44). In contrast, the massA-minus mutant 10.24 was detected at higher populations in the wheat and apple rhizosphere and in soil compared with the wild-type P. fluorescens SS101 at 30 days after the strains were introduced into an orchard soil (41). We found that loss of the ability to produce the viscosin-like CLP had no effect on the ability of HC1-07 to colonize the wheat rhizosphere in the cycling experiment. The slight loss in rhizosphere competence in mutant HC1-07prtR2 may be related to loss of other traits that prtR impacts. The cycling experiment is an especially robust assay to test the role of a trait or gene in root colonization because bacteria introduced into the soil must survive, colonize the root, and then recolonize the root again after surviving in the soil.

In conclusion, our study specifically shows that the biocontrol strain P. fluorescens HC1-07 produces a viscosin-like CLP that plays a key role in the suppression of root diseases of wheat but the CLP does not contribute to the rhizosphere competence of the strain. In a broader context, our results add support to an emerging picture that certain biocontrol microorganisms, mechanisms, metabolites, or genes are cosmopolitan in agro-ecosystems worldwide, where they contribute to some level of natural suppression of soilborne and foliar plant diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Special Fund for Agro-Scientific Research in the Public Interest (200903052 and 201003065), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31171809 and 30971956), and Chinese Scholarship of Research Plan for Joint Educational Ph.D. Program. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

Contributor Information

Ming-Ming Yang, Department of Plant Pathology, College of Plant Protection, Nanjing Agricultural University, Engineering Center of Bioresource Pesticide in Jiangsu Province, Key Laboratory of Monitoring and Management of Crop Diseases and Pest Insects, Ministry of Agriculture, Nanjing, 210095, China. Department of Plant Pathology, Washington State University, Pullman 99164-6430.

Shan-Shan Wen, Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, Washington State University, Pullman 99164-6420.

Dmitri V. Mavrodi, Department of Biological Sciences, The University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg 39406

Olga V. Mavrodi, Department of Plant Pathology, Washington State University, Pullman 99164-6430

Diter von Wettstein, Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, Washington State University, Pullman 99164-6420.

Linda S. Thomashow, United States Department of Agriculture–Agricultural Research Service, Root Disease and Biological Control Research Unit, Pullman, WA 99164-6420

Jian-Hua Guo, Department of Plant Pathology, College of Plant Protection, Nanjing Agricultural University, Engineering Center of Bioresource Pesticide in Jiangsu Province, Key Laboratory of Monitoring and Management of Crop Diseases and Pest Insects, Ministry of Agriculture, Nanjing, 210095, China.

David M. Weller, United States Department of Agriculture–Agricultural Research Service, Root Disease and Biological Control Research Unit, Pullman, WA 99164-6420

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. Short Protocols in Molecular Biology. 5. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bais HP, Fall R, Vivanco JM. Biocontrol of Bacillus subtilis against infection of Arabidopsis roots by Pseudomonas syringae is facilitated by biofilm formation and surfactin production. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:307–319. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.028712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bender CL, Scholz-Schroeder BK. New insights into the biosynthesis, mode of action, and regulation of syringomycin, syringopeptin and coronatine. In: Ramos J-L, editor. Pseudomonas, Vol. 2, Virulence and Gene Regulation. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2004. pp. 125–158. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun PG, Hildebrand PD, Ells TC, Kobayashi DY. Evidence and characterization of a gene cluster required for the production of viscosin, a lipopeptide biosurfactant, by a strain of Pseudomonas fluorescens. Can J Microbiol. 2001;47:294–301. doi: 10.1139/w01-017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burger M, Woods RG, McCarthy C, Beacham IR. Temperature regulation of protease in Pseudomonas fluorescens LS107d2 by an ECF sigma factor and a transmembrane activator. Microbiology. 2000;146:3149–3155. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-12-3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook RJ. Take-all of wheat. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2003;62:73–86. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook RJ, Weller DM, Youssef El-Banna A, Vakoch D, Zhang H. Yield responses of direct-seeded wheat to rhizobacteria and fungicide seed treatments. Plant Dis. 2002;86:780–784. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2002.86.7.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’aes J, De Meyer K, Pauwelyn E, Höfte M. Biosurfactants in plant-Pseudomonas interactions and their importance to biocontrol. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2010;2:359–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’aes J, Hua GK, De Maeyer K, Pannecoucque J, Forrez I, Ongena M, Dietrich LE, Thomashow LS, Mavrodi DV, Höfte M. Biological control of Rhizoctonia root rot on bean by phenazine and cyclic lipopeptide producing Pseudomonas CMR12a. Phytopathology. 2011;101:996–1004. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-11-10-0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Bruijn I, de Kock MJD, de Waard P, van Beek TA, Raaijmakers JM. Massetolide A biosynthesis in Pseudomonas fluorescens. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:2777–2789. doi: 10.1128/JB.01563-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Bruijn I, de Kock MJD, Yang M, de Waard P, van Beek TA, Raaijmakers JM. Genome-based discovery, structure prediction and functional analysis of cyclic lipopeptide antibiotics in Pseudomonas species. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:417–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Bruijn I, Raaijmakers JM. Diversity and functional analysis of LuxR-type transcriptional regulators in cyclic lipopeptide biosynthesis in Pseudomonas fluorescens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:4753–4761. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00575-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennis JJ, Zylstra GJ. Plasposons: Modular self-cloning minitransposon derivatives for rapid genetic analysis of gram-negative bacterial genomes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2710–2715. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2710-2715.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Souza JT, de Boer M, de Waard P, van Beek TA, Raaijmakers JM. Biochemical, genetic, and zoosporicidal properties of cyclic lipopeptide surfactants produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:7161–7172. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7161-7172.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubern JF, Coppoolse ER, Stiekema WJ, Bloemberg FV. Genetic and functional characterization of the gene cluster directing the biosynthesis of putisolvin I and II in Pseudomonas putida strain PCL1445. Microbiology. 2008;154:2070–2083. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/016444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubern JF, Lagendijk EL, Lugtenberg BJJ, Bloemberg GV. The heat shock genes dnaK, dnaJ, and grpE are involved in regulation of putisolvin biosynthesis in Pseudomonas putida PCL1445. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5967–5976. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.17.5967-5976.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubern JF, Lugtenberg BJJ, Bloemberg GV. The ppuI-rsaL-ppuR quorum-sensing system regulates biofilm formation of Pseudomonas putida PCL1445 by controlling biosynthesis of the cyclic lipopeptides putisolvins I and II. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:2898–2906. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.8.2898-2906.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finking R, Marahiel MA. Biosynthesis of non-ribosomal peptides. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2004;58:453–488. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fogliano V, Ballio A, Gallo M, Woo S, Scala F, Lorito M. Pseudomonas lipodepsipeptides and fungal cell wall-degrading enzymes act synergistically in biological control. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2002;15:323–333. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haas D, Défago G. Biological control of soil-borne pathogens by fluorescent pseudomonads. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:307–319. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haas D, Keel C. Regulation of antibiotic production in root-colonizing Pseudomonas spp. and relevance for biological control of plant diseases. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2003;41:117–153. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.41.052002.095656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hildebrand PD, Braun PG, McRae KB, Lu X. Role of the biosurfactant viscosin in broccoli head rot caused by a pectolytic strain of Pseudomonas fluorescens. Can J Plant Pathol. 1998;20:296–303. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong J, Miao R, Zhao CM, Jiang J, Tang HW, Guo ZJ, Zhu LG. Mass spectrometry assisted assignments of binding and cleavage sites of copper(II) and platinum(II) complexes towards oxidized insulin B chain. J Mass Spectrom. 2006;41:1061–1072. doi: 10.1002/jms.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howell CR, Stipanovic RD. Control of Rhizoctonia solani on cotton seedlings with Pseudomonas fluorescens and with an antibiotic produced by the bacterium. Phytopathology. 1979;69:480–482. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howell CR, Stipanovic RD. Suppression of Pythium ultimum-induced damping-off of cotton seedlings by Pseudomonas fluorescens and its antibiotic, pyoluteorin. Phytopathology. 1980;70:712–715. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang ZY, Bonsall RF, Mavrodi DV, Weller DM, Thomashow LS. Transformation of Pseudomonas fluorescens with genes for biosynthesis of phenazine-1-carboxylic acid improves biocontrol of Rhizoctonia root rot and in situ antibiotic production. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2004;49:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim BS, Lee JY, Hwang BK. In vitro control and in vitro antifungal activity of rhamnolipid B, a glycilipid antibiotic, against Phytophthora capsici and Colletotrichum orbiculare. Pest Manage. Sci. 2000;56:1029–1035. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim DS, Cook RJ, Weller DM. Bacillus sp. L324-92 for biological control of three root diseases of wheat grown with reduced tillage. Phytopathology. 1997;87:551–558. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1997.87.5.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King EO, Ward MK, Raney DE. Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescein. J Lab Clin Med. 1954;44:301–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kochi M, Weiss DW, Pugh L, Groupe V. Viscosin, a new antibiotic. Bacteriol Proc. 1951;1:29–30. doi: 10.3181/00379727-78-19071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwak YS, Bakker PAHM, Glandorf DCM, Rice JT, Paulitz TC, Weller DM. Diversity, virulence, and 2,4-diacetyl-phloroglucinol sensitivity of Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici isolates from Washington State. Phytopathology. 2009;99:472–479. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-99-5-0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwak YS, Bonsall RF, Okubara PA, Paulitz TC, Thomashow LS, Weller DM. Factors impacting the activity of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas fluorescens against take-all of wheat. Soil Biol Biochem. 2012;54:48–56. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landa BB, de Werd HA, McSpadden Gardener BB, Weller DM. Comparison of three methods for monitoring populations of different genotypes of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas fluorescens in the rhizosphere. Phytopathology. 2002;92:129–137. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2002.92.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lawrence RC, Fryer TF, Reiter B. Rapid method for the quantitative estimation of microbial lipases. Nature. 1967;213:1264–1265. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lugtenberg B, Kamilova F. Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2009;63:541–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacNish GC. Changes in take-all (Gaeumannomyces graminis vartritici), Rhizoctonia root rot (Rhizoctonia solani) and soil pH in continuous wheat with annual applications of nitrogenous fertilizer in Western Australia. Aust J Exp Agric. 1988;28:333–341. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mavrodi DV, Blankenfeldt W, Thomashow LS. Phenazine compounds in fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. biosynthesis and regulation. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2006;44:417–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.44.013106.145710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mavrodi DV, Bonsall RF, Delaney SM, Soule MJ, Phillips G, Thomashow LS. Functional analysis of genes for biosynthesis of pyocyanin and phenazine-1-carboxamide from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:6454–6465. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6454-6465.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mavrodi OV, Mavrodi DV, Weller DM, Thomashow LS. The role of dsbA in root colonization by Pseudomonas fluorescens Q8r1-96. Microbiology. 2006;152:863–872. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mavrodi OV, McSpadden Gardener BB, Bonsall RF, Weller DM, Thomashow LS. Genetic diversity of phlD from 2,4-diacetyl-phloroglucinol-producing fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. Phytopathology. 2001;91:35–43. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2001.91.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mazzola M, Zhao X, Cohen MF, Raaijmakers JM. Cyclic lipopeptide surfactant production by Pseudomonas fluorescens SS101 is not required for suppression of complex Pythium spp. population. Phytopathology. 2007;97:1348–1355. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-97-10-1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McSpadden Gardener BB, Mavrodi DV, Thomashow LS, Weller DM. A rapid polymerase chain reaction-based assay characterizing rhizosphere populations of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing bacteria. Phytopathology. 2001;91:44–54. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2001.91.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nielsen TH, Christophersen C, Anthoni U, Sorensen J. Viscosinamide, a new cyclic depsipeptide with surfactant and antifungal properties produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens DR54. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;86:80–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nielsen TH, Nybroe O, Koch B, Hansen M, Sorensen J. Genes involved in cyclic lipopeptide production are important for seed and straw colonization by Pseudomonas sp. strain DSS73. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:4112–4116. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.4112-4116.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nielsen TH, Sorensen J. Production of cyclic lipopeptides by Pseudomonas fluorescens strains in bulk soil and in the sugar beet rhizosphere. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:861–868. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.2.861-868.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Toole GA, Kolter R. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple convergent signaling pathways: A genetic analysis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:449–461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paulitz TC, Okubara PA, Schroeder KL. Integrated control of soilborne pathogens of wheat. In: Gisi ICU, Gullino M, editors. Recent Developments in Management of Plant Diseases. Plant Pathology in the 21st Century. Vol. 1. Springer; Dordrecht, the Netherlands: 2009. pp. 229–245. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paulitz TC, Schroeder KL, Schillinger WF. Soilborne pathogens of cereals in an irrigated cropping system: Effects of tillage, residue management, and crop rotation. Plant Dis. 2010;94:61–68. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-94-1-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paulitz TC, Smiley RW, Cook RJ. Insights into the prevalence and management of soilborne cereal pathogens under direct seeding in the Pacific Northwest, U.S.A. Can J Plant Pathol. 2002;24:416–428. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perneel M, D’hondt L, De Maeyer K, Adiobo A, Rabaey K, Höfte M. Phenazines and biosurfactants interact in the biological control of soil-borne diseases caused by Pythium spp. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:778–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pierson EA, Weller DM. Use of mixtures of fluorescent Pseudomonads to suppress take-all and improve the growth of wheat. Phytopathology. 1994;84:940–947. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Raaijmakers JM, de Bruijn I, de Kock MJD. Cyclic lipopeptide production by plant-associated Pseudomonas spp.: Diversity, activity, biosynthesis, and regulation. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2006;19:699–710. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raaijmakers JM, De Bruijn I, Nybroe O, Ongena M. Natural functions of lipopeptides from Bacillus and Pseudomonas: more than surfactants and antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2010;34:1037–1062. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roget DK. Decline in root rot (Rhizoctonia solani AG-8) in wheat in a tillage and rotation experiment at Avon, South Australia. Aust J Exp Agric. 1995;35:1009–1013. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shin SH, Lim Y, Lee SE, Yang NW, Rhee JH. CAS agar diffusion assay for the measurement of siderophores in biological fluids. J Microbiol Methods. 2001;44:89–95. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(00)00229-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soler-Rivas C, Jolivet S, Arpin N, Olivier JM, Wichers HJ. Biochemical and physiological aspects of brown blotch disease of Agaricus bisporus. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1999;23:591–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1999.tb00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stanghellini ME, Miller RM. Biosurfactants: Their identity and potential efficacy in the biological control of zoosporic plant pathogens. Plant Dis. 1997;81:4–12. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1997.81.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thomashow LS, Weller DM. Role of a phenazine antibiotic from Pseudomonas fluorescens in biological control of Gaeumannomyces graminis var tritici. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3499–3508. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.8.3499-3508.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tran H, Ficke A, Asiimwe T, Höfte M, Raaijmakers JM. Role of the cyclic lipopeptide massetolide A in biological control of Phytophthora infestans and in colonization of tomato plants by Pseudomonas fluorescens. New Phytol. 2007;175:731–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van den Broek D, Chin-A-Woeng TFC, Eijkemans K, Mulders IHM, Bloemberg GV, Lugtenberg BJJ. Biocontrol traits of Pseudomonas spp. are regulated by phase variation. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2003;16:1003–1012. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.11.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weller DM, Cook RJ. Suppression of take-all of wheat by seed treatments with fluorescent Pseudomonads. Phytopathology. 1983;73:463–469. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weller DM, Landa BB, Mavrodi OV, Schroeder KL, De La Fuente L, Blouin Bankhead S, Allende Molar R, Bonsall RF, Mavrodi DV, Thomashow LS. Role of 2,4-diacetyl-phloro-glucinol-producing fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. in the defense of plant roots. Plant Biol. 2007;9:4–20. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weller DM, Raaijmakers JM, Gardener BB, Thomashow LS. Microbial populations responsible for specific soil suppressiveness to plant pathogens. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2002;40:309–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.40.030402.110010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang MM, Mavrodi DV, Mavrodi OV, Bonsall RF, Parejko JA, Paulitz TC, Thomashow LS, Yang HT, Weller DM, Guo JH. Biological control of take-all by fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. from Chinese wheat fields. Phytopathology. 2011;101:1481–1491. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-04-11-0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.