Abstract

Introduction

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is characterized by precapillary pulmonary hypertension secondary to vaso-occlusive pulmonary vasculopathy and is classified as Pulmonary Hypertension Group 4. The aim of this study is to report the clinical experience of CTEPH in Mexico.

Methods

Consecutive patients diagnosed with CTEPH were identified from the Registro de Pacientes con Hipertension Pulmonar del Instituto de Seguridad y Servicio Social de los Trabajadores del Estado (REPHPISSSTE) registry between January 2009 and February 2014. Right heart catheterization was not routinely performed prior to August 2010 in the work-up of CTEPH.

Results

We identified 50 patients with CTEPH; their median age was 63 years and 58 % were female. Patients had multiple associated co-morbidities and moderate hemodynamic impairment. All patients were treated with anticoagulation. Despite surgical evaluation for pulmonary endarterectomy (PEA), only one patient underwent PEA given the lack of infrastructure for post-operative care and lack of insurance for this procedure. Most of the patients were treated with sildenafil, bosentan, or both, with increasing use of rivaroxaban and sildenafil in recent years. The overall survival of the cohort was similar to that reported in other international registries, despite the limitations of care imposed by drug availability and surgical feasibility.

Conclusion

This is the first report on the CTEPH experience in Mexico. It highlights the similarity of patients in the REPHPISSSTE registry to those in international registries as well as the challenges that clinicians face in a resource-limited setting.

Keywords: Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, Survival, Pulmonary endarterectomy, Management

Introduction

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is caused by chronic obstruction of the pulmonary vasculature by thromboemboli and is classified as Group 4 Pulmonary Hypertension (PH) [1, 2]. CTEPH is defined as precapillary PH with associated elevations in pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) and vascular resistance (PVR), which, untreated, commonly lead to right ventricular (RV) dysfunction, right heart failure, and death [1, 3, 4]. Risk factors for CTEPH include thromboembolic events, splenectomy, intravascular catheters, malignancy, thyroid replacement therapy, and thrombophilia [5–7].

Unlike pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), CTEPH is potentially curable by pulmonary endarterectomy (PEA) [3, 8]; however, the criteria for surgical operability are variable and largely depend on the center’s practices and experience [9, 10]. In addition, for patients with inoperable disease and or persistent or recurrent PH after PEA, riociguat is the only medical therapy thus far approved as effective to treat CTEPH [11]. Riociguat was not yet available in Mexico at the time of this study. Prior to riociguat, medical therapy for CTEPH was extrapolated from medical therapy for Group 1 PAH including endothelin receptor antagonists, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, and prostacyclins [3, 12].

The incidence of CTEPH has been reported to be between <1 % and upwards of 10 % after a symptomatic pulmonary embolism [3]. Conversely, up to 50 % of patients with CTEPH have not had an identifiable acute thromboembolic event [13, 14]. The magnitude and clinical outcomes of patients with CTEPH have been reported mainly from observational registries in the United States, Europe, Japan, and China [3, 15-21].

Because of the dearth of epidemiologic information on the characteristics and management of newly diagnosed CTEPH in the developing world, we examined these factors in a population of patients with CTEPH presenting to a large PH referral center in Mexico City, Mexico.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This is a prospective study of consecutive, newly diagnosed CTEPH patients referred to the Instituto de Seguridad y Servicio Social de los Trabajadores del Estado (ISSSTE) and the Hospital Regional 1° de Octubre and included in the Registro de Pacientes con Hipertension Pulmonar del Instituto de Seguridad y Servicio Social de los Trabajadores del Estado (REPHPISSSTE) registry, from January 2009 to February 2014. The REPHPISSSTE is a comprehensive systematic database of patients with pulmonary hypertension Group 1 (PAH) and 4 (CTEPH) followed at either the ISSSTE hospital or the Hospital Regional 1° de Octubre in Mexico City, Mexico. Inclusion in the registry did not influence the management of the patients by their respective physicians. Right heart catheterization (RHC) was not routinely performed to diagnose CTEPH until after August 2010; therefore, the cohort was divided into two groups: a historical cohort (January 2009 to July 2010) and a contemporary cohort (August 2010 to December 2013). Patients were followed until death or March 31, 2014. The study was approved by the institutional review board at ISSSTE and the Hospital Regional 1° de Octubre.

Study Subjects

Patients were included if they were ≥18 years of age with PH as defined by a mean PAP (mPAP) ≥25 mm Hg and a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) ≤15 mm Hg. Prior to August 2010, PH was diagnosed based on an elevated estimated systolic PAP ≥45 mm Hg with or without RV dysfunction by echocardiography. CTEPH was confirmed by radiographic abnormalities consistent with multiple filling defects detected on ventilation–perfusion (V/Q) lung scintigraphy, computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA), or pulmonary angiography. All patients had been receiving anticoagulation for at least 6 months at enrollment. Eligibility for PEA operability was assessed retrospectively for patients who did not have a diagnostic RHC and prospectively for those who did. The operability assessment was performed by a team of physicians that included a PH specialist, a radiologist, and a thoracic surgeon with special interest in PEA. At enrollment, patients had not been previously treated medically with PAH-specific therapies.

Data Collection

Data collected included patients’ demographic characteristics, medical history, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, blood tests and diagnostic tests, procedures, treatments, and dates of deaths.

Statistical Analysis

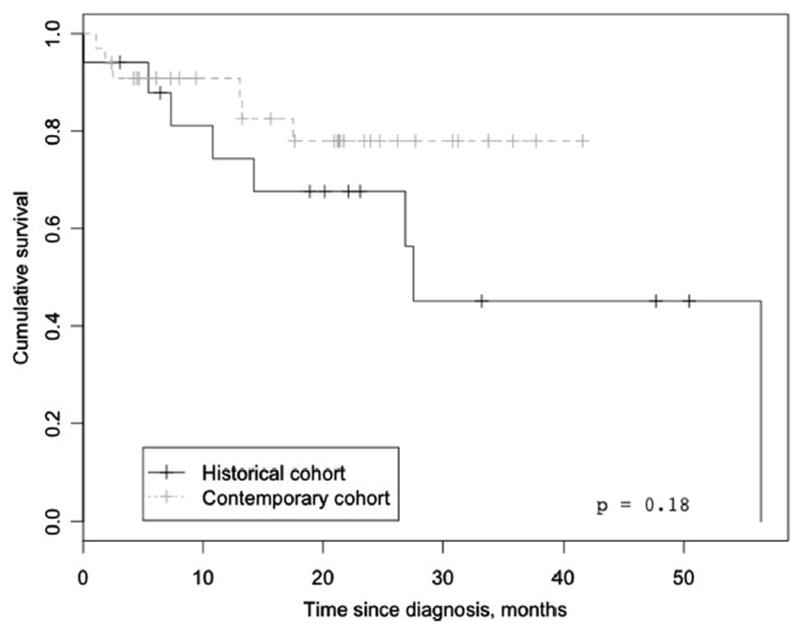

Categorical data were expressed as counts and percentages, and continuous variables were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges. Differences between groups were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Kaplan–Meier curves were used to compare survival among patients who underwent RHC evaluation and those who did not. Since all patients were newly diagnosed upon enrollment, survival time was defined by the date of the echocardiographic assessment in the historical cohort and the date of diagnostic RHC in the contemporary cohort. Survival was censored on March 31, 2014. All analyses were performed using R version 3.1.1. The reported p values are exploratory in nature.

Results

Seventy-one patients newly diagnosed with CTEPH were identified in the REPHPISSSTE registry between January 2009 and December 2013. Twenty-one patients were subsequently followed by their local physicians and were lost to follow-up. The remaining 50 patients were divided into the historical cohort (January 2009 to July 2010, n = 17) and the contemporary cohort (August 2010 to December 2013, n = 33) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for patients in the study cohort and outcomes

The median age was 63 years (IQR 53–75 years) and 58 % were females (Table 1). About half of the patients had a prior diagnosis of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and the median time from VTE to CTEPH diagnosis was 3 years (IQR 2–16 years). Patients in the contemporary cohort were younger than patients in the historical cohort (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristic at the time of diagnosis

| All patients (n = 50) | Contemporary cohort (n = 33) | Historical cohort (n = 17) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63 (53–75) | 61 (49–73) | 70 (62–78) | 0.04 |

| Female, n (%) | 29 (58) | 19 (58) | 10 (59) | 1.00 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.5 (24.0–40.5) | 33.0 (25.0–42.0) | 25.0 (23.0–35.0) | 0.07 |

| Previous diagnosis of VTE | ||||

| Deep venous thrombosis, n (%) | 23 (46) | 18 (55) | 5 (29) | 0.14 |

| Acute pulmonary embolism, n (%) | 21 (42) | 17 (52) | 4 (24) | 0.07 |

| Time from prior VTE to CTEPH diagnosis, years | 3 (2–16) | 3 (2–7) | 3 (2–5) | 0.75 |

| Coagulation profile | ||||

| Protein C deficiency, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Protein S deficiency, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Antiphospholipid antibody, n (%) | 3 (6) | 3 (9) | 0 (0) | 0.54 |

| Lupus anticoagulant, n (%) | 4 (8) | 3 (9) | 1 (6) | 1.00 |

| Factor V leiden mutation n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Antithrombin III deficiency, n (%) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.01 |

Results shown as median (Interquartile range). p value reported between the contemporary and historical groups VTE venous thromboembolism

Blood testing for thrombotic disorders was performed at the time of CTEPH diagnosis. Antithrombin III deficiency was more common in the contemporary group (Table 1). The most frequent established thrombotic risk factor identified was lupus anticoagulant (8 %) followed by antiphospholipid antibodies (6 %) and antithrombin III deficiency (2 %). No patients had a protein C or S deficiency, or a mutation in factor V Leiden.

Multiple co-morbidities were identified at the time of diagnosis (Table 2), but no significant differences were identified between the two cohorts. About 40 % of the study cohort was obese, one-third had hypertension, one-third had obstructive sleep apnea, and less than 10 % had a diagnosis of thrombotic disorder prior to the diagnosis of CTEPH.

Table 2.

Co-morbid conditions at the time of diagnosis

| All patients (n = 50) | Contemporary cohort (n = 33) | Historical cohort (n = 17) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity, n (%) | 20 (40) | 16 (48) | 4 (24) | 0.13 |

| Systemic hypertension, n (%) | 17 (34) | 9 (27) | 8 (47) | 0.21 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea, n (%) | 13 (27) | 11 (34) | 2 (12) | 0.11 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 11 (22) | 5 (15) | 6 (35) | 0.15 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 7 (14) | 4 (12) | 3 (18) | 0.68 |

| Type II diabetes mellitus | 7 (14) | 5 (15) | 2 (12) | 1.00 |

| Cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 6 (12) | 3 (9) | 3 (18) | 0.40 |

| Interstitial lung disease, n (%) | 3 (6) | 1 (3) | 2 (12) | 0.26 |

| Major surgery, n (%) | 3 (6) | 3 (9) | 0 (0) | 0.54 |

| Thrombotic disorder, n (%) | 3 (6) | 3 (9) | 0 (0) | 0.54 |

| Thyroid disorder, n (%) | 3 (6) | 1 (3) | 2 (12) | 0.26 |

| Asthma, n (%) | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | 1 (6) | 1.00 |

| Pregnancy, n (%) | 2 (4) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 0.54 |

| Cancer, n (%) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 0.34 |

p value reported between the contemporary and historical groups

Functional Classification

At the time of diagnosis, most of the patients were significantly limited (NYHA class III or IV). A 6-min walk test was performed in 39 patients at the time of diagnosis. The median of 6-min walk distance (6MWD) was 289 m (IQR 182–402). There were no differences in NYHA class or 6MWD between the two groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Diagnostic testing and functional classification at the time of diagnosis

| All patients (n = 50) | Contemporary cohort (n = 33) | Historical cohort (n = 17) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NYHA functional class, n (%) | 0.54 | |||

| II | 9 (18) | 5 (15) | 4 (24) | |

| III | 29 (58) | 21 (64) | 8 (47) | |

| IV | 12 (24) | 7 (21) | 5 (29) | |

| 6 min walk distance (n = 39), m V/Q scan (n = 42), n (%) | 289 (182–402) | 285 (182–411) | 307 (172–359) | 0.82 |

| Abnormal perfusion | 42 (100) | 30 (100) | 12 (100) | 1.00 |

| Abnormal ventilation | 13 (31) | 8 (27) | 5 (42) | 0.46 |

| CT angiography, n (%) | ||||

| Proximal occlusive lesions | 16 (33) | 11 (33) | 5 (33) | 1.00 |

| Dilation of pulmonary arteries | 20 (42) | 13 (39) | 7 (47) | 0.76 |

| Mosaic perfusion pattern | 20 (42) | 16 (48) | 4 (27) | 0.21 |

| Echocardiographic findings | ||||

| RV dilatation, n (%) | 47 (94) | 30 (91) | 17 (100) | 0.54 |

| PASP, mmHg | 65 (58–75) | 67 (58–74) | 60 (53–75) | 0.36 |

| TAPSE (n = 43), mm | 18 (16–19) | 18 (17–20) | 17 (13–19) | 0.14 |

| Spirometry | ||||

| FEV1 (n = 44), liters | 2.35 (1.80–2.95) | 2.60 (2.10–3.10) | 1.80 (1.70–2.28) | 0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC (n = 44), % | 68 (63–84) | 69 (65–82) | 65 (62–83) | 0.21 |

| Abnormal DLCO (n = 37), n (%) | 8 (22) | 3 (11) | 5 (56) | 0.01 |

| Hemodynamics by RHC | ||||

| MPAP, mmHg | – | 35 (31–43) | – | – |

| Cardiac index (TD), L/min/m2 | – | 2.40 (2.20–2.90) | – | – |

| PVR, Wood units | – | 8.1 (5.6–10.6) | – | – |

p value reported between the contemporary and historical groups

RHC right heart catheterization, NYHA New York Heart Association, V/Q ventilation–perfusion lung scintigraphy, RV right ventricle, PASP pulmonary artery systolic pressure, TAPSE tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in first second, FVC forced vital capacity, DLCO diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide, MPAP mean pulmonary artery pressure, PVR pulmonary vascular resistance, TAPSE tricuspid annular planar systolic excursion, TD thermodilution

Radiographic Findings

Abnormal perfusion was detected in all study patients who underwent a V/Q scan (n = 42), and abnormal ventilation was detected in approximately 30 %. All patients underwent a CTPA, and proximal lesions were detected in 33 % of the scans. Dilation of pulmonary arteries and mosaic perfusion pattern were detected in approximately 40 % of all the scans. Pulmonary angiography was performed in the one patient that underwent PEA.

Spirometry

Spirometry was available in 44 patients. The median FEV1/ FVC ratio was 68 % with no difference between the historical and contemporary groups (Table 3); however, patients in the contemporary group had significantly better FEV1 as compared to the patients in the historical group (2.60 liters vs. 1.80 liters, p = 0.001). Abnormal diffusion capacity was reported in 22 % of patients, with more patients in the historical group having lung diffusion capacity abnormalities as compared to the contemporary group (56 vs. 11 %, p = 0.01).

Echocardiographic Findings

RV dilatation was documented in 94 % of patients (Table 3). The estimated systolic PAP was elevated, with a median of 65 mm Hg (IQR 58–75 mm Hg). The tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) was measured in 43 patients and had a median of 18 mm (IQR 16–19 mm).

Invasive Hemodynamic Parameters

The mPAP was mildly elevated (median 35 mm Hg, IQR 31–43 mm Hg); however, PVR was substantially elevated (median of 8.1 Woods units, IQR 5.6–10.6 WU) and cardiac index tended to be low (median of 2.4 liters/min/m2 (IQR 2.2–2.9 L/min/m2) (Table 3).

Surgical Operability

Operability was assessed retrospectively in 12 patients in the historical group, by chart review, and 7 patients (58 %) were deemed operable but none underwent PEA (Table 4).

Table 4.

Long-term management of CTEPH

| All patients (n = 50) | Contemporary cohort (n = 33) | Historical cohort (n = 17) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticoagulationa | ||||

| Warfarin, n (%) | 29 (59) | 16 (50) | 13 (76) | 0.13 |

| Rivaroxaban, n (%) | 25 (51) | 21 (66) | 4 (24) | 0.007 |

| Enoxaparin, n (%) | 5 (10) | 3 (9) | 2 (12) | 1.00 |

| Digoxin, n (%) | 19 (38) | 9 (27) | 10 (59) | 0.04 |

| PAH-specific therapy | ||||

| Sildenafil, n (%) | 35 (70) | 27 (82) | 8 (47) | 0.02 |

| Bosentan, n (%) | 5 (10) | 5 (15) | 0 (0) | 0.15 |

| Inhaled iloprost, n (%) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| IVC filter placement, n (%) | 8 (16) | 3 (9) | 5 (29) | 0.10 |

| PEA, n (%) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Recurrence of VTE, n (%) | 9 (20) | 7 (21) | 2 (18) | 1.00 |

p value reported between the contemporary and historical groups

PAH pulmonary arterial hypertension, IVC inferior vena cava, PEA pulmonary artery endarterectomy, VTE venous thromboembolism

Patients may have received two different forms of anticoagulation

Patients in the contemporary group were assessed for operability prospectively. Among those, 22 patients (67 %) were deemed operable but only one patient, who also had a right atrial thrombus, underwent PEA and thrombectomy of the cardiac clot. The patient recovered with residual mild PH postoperatively which was treated with sildenafil. The main reason for not operating on the remaining 21 patients was lack of insurance coverage for this surgery.

Pharmacologic and Non-pharmacologic Management

All patients received anticoagulation (Table 4). Ten patients were initiated on warfarin and later switched to enoxaparin or the newer oral anticoagulant (NOAC) rivaroxaban; however, more patients in the contemporary group were initiated on or switched to rivaroxaban than patients in the historical group (66 vs. 24 %, p = 0.007). More than one-third of patients received digoxin including 59 % patients in the historical group and 27 % in the contemporary group (p = 0.04). Fourteen patients (28 %) received no PAH-specific therapy. The majority of patients (70 %) who were treated with PAH-specific medication received sildenafil, with a greater percentage of patients in the contemporary group treated with sildenafil as compared to the historical group. Ten percent of patients were treated with bosentan, and one was treated with inhaled iloprost. Inferior vena cava (IVC) filters were not frequently deployed, with only 16 % receiving an IVC filter after the diagnosis of CTEPH.

Follow-Up and Outcomes

Patients were followed for a median of 20 months (7–26 months). By the end of the study, 14 patients (21 %) were dead (six in the contemporary and eight in the historical group). There was no significant difference in survival between the two cohorts (Fig. 2). VTE recurrence was documented in 20 % of patients and it was similar between groups, regardless of anticoagulant (Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Overall survival of patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension in Mexico

Discussion

This is the first report on the characteristics and management of patients with CTEPH from Mexico. Our study describes patient characteristics at the time of diagnosis and their long-term outcomes. We describe changes in the management of these patients, most notably the implementation of diagnostic RHC in 2010 for the confirmation of PH and the increased use of NOACs. Our main findings are that patients presenting with CTEPH comprise a predominantly middle aged, obese patient population with multiple co-morbidities with advanced pulmonary vascular disease at the time of diagnosis as evidenced by abnormal RV function on echocardiography and a borderline-low cardiac index at RHC. Our study also demonstrates that most of the patients do not undergo PEA, even potentially operable candidates.

Registries from the United States [22], Japan [23], Europe [12, 17], and Canada [12] report a median age of CTEPH patients of approximately 63 years, comparable to our cohort. The slight female predominance observed in our study is consistent with the findings from the International registry [12]. We also noted a history of VTE in 46 % of patients diagnosed with CTEPH, similar to findings from other registries [3, 12, 22, 23]. This study, in contrast to previously published data, reports a lower prevalence of established thrombotic risk factors, with lupus anticoagulant and antiphospholipid antibodies occurring in 6 and 8 % of patients, respectively, as opposed to 10 % and 20 % in an earlier study [24]. This difference could be a random variation between study populations, but we cannot exclude the possibility of genetic differences.

RHC was not routinely performed in the study centers prior to August 2010 and the diagnosis of PH was based solely on echocardiographic findings. Nevertheless, the echocardiographic findings were similar between the patients who underwent a confirmatory RHC and those who did not. All patients in the historical group had abnormal RV function in the setting of clinical and radiologic assessments consistent with the diagnosis of CTEPH. For contemporary patients who underwent RHC, pulmonary hemodynamics were comparable to previous reports [12, 22, 23, 25], with mPAP only modestly elevated (median 35 mm Hg) and cardiac index borderline low. The latter finding, combined with the high incidence of RV dysfunction on echocardiography, suggests advanced disease.

Even though PEA is a potentially curative therapy for patients with CTEPH, there are no defined criteria for discriminating surgically accessible obstructive lesions from inaccessible lesions [9, 10, 26-28]. Assessment of operability remains in large part surgeon- and center-dependent. In the current study, about two-third of patients were deemed operable based on a review of their radiographic images and their clinical profile; however, only one patient underwent PEA. This is due to the lack of infrastructure in Mexico to perform these operations, lack of reimbursement for the procedure, lack of ability to provide the complex post-operative care needed, or funds to obtain the surgery elsewhere. In our cohort, the only patient who underwent PEA had another indication for surgery, a right atrial thrombus, which facilitated insurance approval and allowed a combined surgery to occur with a favorable postoperative outcome: improvement in his hemodynamics, but residual mild PH that was treated with oral sildenafil. However, resources to provide this surgery are lacking not only in Mexico City but also in many other developing countries. In addition, among oral PAH-specific medications, only sildenafil and bosentan were available in Mexico during the study period, both of which have previously produced mixed results in patients with CTEPH [29-32]. Seventy percent of patients in this study received either sildenafil or bosentan or both in addition to anticoagulation. Since these results were compiled, riociguat has been approved to treat CTEPH in Mexico, but no data are yet available on its use there.

The predominant anticoagulant used differed significantly between the two groups. Since the NOACs are associated with better compliance and ease of administration than warfarin [33] and in the absence of data favoring one type of anticoagulation over the other in patients with CTEPH, the more recently enrolled contemporary patients received rivaroxaban more often than warfarin. Rates of VTE recurrence did not differ between the historical and contemporary groups, suggesting similar anticoagulant efficacy, although this was not formally tested. The rate of recurrent thrombotic events in our study was also similar to previous reports [12]. In addition, similar to the CTEPH international registry [12], IVC filters were placed less often in our cohorts than in US-based registries [27, 34] where IVC filters are placed preoperatively.

While patients in our cohort had less severe elevations of mPAP as compared to other contemporary registries [12, 22, 25], the overall survival of CTEPH patients in our cohort was about 80 % at 2 years of follow-up. In a prospective international registry, the 3-year survival rate for CTEPH patients who were operated on was 89 % as compared with a rate of 70 % for those not operated on [35]. The superior survival rates with PEA as compared with non-specific medical therapy in operable candidates could be due to selection bias with patients not undergoing PEA being a sicker cohort, but it still re-emphasizes the importance of assessing surgical operability at diagnosis. On the other hand, appropriate medical therapy should be instituted without delay in areas (like Mexico) where access to PEA is limited, but not if it leads to unnecessary delays in surgery [36].

Our study is an observational, single-center registry, which has inherent study design limitations with a relatively small number of patients and changes in practice over time. However, our study describes the systematic management of a rare disease in a country representative of health care delivery in the developing world. Since the majority of patients were treated with oral sildenafil, we did not have sufficient power to compare differences in outcomes by different PAH-specific medications.

In conclusion, CTEPH is an increasingly recognized condition worldwide with a potentially curable surgical treatment [37]. This is the first report of the clinical characteristics of patients with CTEPH presenting to referral centers in Mexico, and the first report of a prospective database from a region of the world without full access to medical and surgical therapies for CTEPH. In this context, even though medical therapies have evolved in recent years with the greater use of NOACs and PAH-specific medical therapies, current practices may be dictated by limitations in medical and surgical resources rather than evidence-based approaches.

Acknowledgments

Dr Al-Naamani is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Grant Number UL1 TR001064 and TL1 TR001062.

Dr Espitia has received an unrestricted grant from Bayer de Mexico S.A. de C.V. Dr Hill has received research grant support from Actelion, Gilead, Bayer, United Therapeutics, and Reata; has served on the medical advisory board for Gilead and Bayer; and has served on the data monitoring committee for Lung LLC (Limited Liability Company). Dr Preston has received grant support from Actelion, Bayer, Gilead, and United Therapeutics; and has served as a consultant for Actelion, Bayer, Gilead, United Therapeutics, and Pfizer.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest All other authors have reported no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Auger WR, Kim NH, Kerr KM, et al. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Clin Chest Med. 2007;28:255–269x. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lang IM, Pesavento R, Bonderman D, et al. Risk factors and basic mechanisms of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a current understanding. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:462–468. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00049312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lang IM, Madani M. Update on chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2014;130:508–518. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riedel M, Stanek V, Widimsky J, et al. Longterm follow-up of patients with pulmonary thromboembolism. Late prognosis and evolution of hemodynamic and respiratory data. Chest. 1982;81:151–158. doi: 10.1378/chest.81.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonderman D, Wilkens H, Wakounig S, et al. Risk factors for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:325–331. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00087608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li JF, Lin Y, Yang YH, et al. Fibrinogen Aalpha Thr312Ala polymorphism specifically contributes to chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension by increasing fibrin resistance. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e69635. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris TA, Marsh JJ, Chiles PG, et al. High prevalence of dysfibrinogenemia among patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Blood. 2009;114:1929–1936. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-208264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim NH, Delcroix M, Jenkins DP, et al. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:D92–D99. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Armini AM, Morsolini M, Mattiucci G, et al. Pulmonary endarterectomy for distal chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:1005–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.06.052. 1012 e1–e2; discussion 1011–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galie N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), endorsed by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2493–2537. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghofrani HA, D’Armini AM, Grimminger F, et al. Riociguat for the treatment of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:319–329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pepke-Zaba J, Delcroix M, Lang I, et al. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH): results from an international prospective registry. Circulation. 2011;124:1973–1981. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.015008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang I, Kerr K. Risk factors for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:568–570. doi: 10.1513/pats.200605-108LR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Condliffe R, Kiely DG, Gibbs JS, et al. Prognostic and aetiological factors in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:332–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00092008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Condliffe R, Kiely DG, Gibbs JS, et al. Improved outcomes in medically and surgically treated chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:1122–1127. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1841OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coronel ML, Chamorro N, Blanco I, et al. Medical and surgical management for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a single center experience. Arch Bronconeumol. 2014;50:521–527. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Escribano-Subias P, Blanco I, Lopez-Meseguer M, et al. Survival in pulmonary hypertension in Spain: insights from the Spanish registry. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:596–603. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00101211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gan HL, Zhang JQ, Bo P, et al. The actuarial survival analysis of the surgical and non-surgical therapy regimen for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2010;29:25–31. doi: 10.1007/s11239-009-0319-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marini C, Formichi B, Bauleo C, et al. Improved survival in patients with inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Intern Emerg Med. 2013;8:307–316. doi: 10.1007/s11739-011-0610-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishimura R, Tanabe N, Sugiura T, et al. Improved survival in medically treated chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Circ J. 2013;77:2110–2117. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-12-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wieteska M, Biederman A, Kurzyna M, et al. Outcome of medically versus surgically treated patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2016;22(1):92–99. doi: 10.1177/1076029614536604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madani MM, Auger WR, Pretorius V, et al. Pulmonary endarterectomy: recent changes in a single institution’s experience of more than 2,700 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.04.004. discussion 103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanabe N, Sugiura T, Tatsumi K. Recent progress in the diagnosis and management of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Respir Investig. 2013;51:134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonderman D, Turecek PL, Jakowitsch J, et al. High prevalence of elevated clotting factor VIII in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90:372–376. doi: 10.1160/TH03-02-0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lang IM, Simonneau G, Pepke-Zaba JW, et al. Factors associated with diagnosis and operability of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. A case-control study Thromb Haemost. 2013;110:83–91. doi: 10.1160/TH13-02-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corsico AG, D’Armini AM, Cerveri I, et al. Long-term outcome after pulmonary endarterectomy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:419–424. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200801-101OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jamieson SW, Kapelanski DP, Sakakibara N, et al. Pulmonary endarterectomy: experience and lessons learned in 1,500 cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:1457–1462. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00828-2. discussion 1462–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morsolini M, Nicolardi S, Milanesi E, et al. Evolving surgical techniques for pulmonary endarterectomy according to the changing features of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension patients during 17-year single-center experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghofrani HA, Schermuly RT, Rose F, et al. Sildenafil for long-term treatment of nonoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1139–1141. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1157BC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reichenberger F, Voswinckel R, Enke B, et al. Long-term treatment with sildenafil in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:922–927. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00039007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonderman D, Nowotny R, Skoro-Sajer N, et al. Bosentan therapy for inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 2005;128:2599–2603. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jais X, D’Armini AM, Jansa P, et al. Bosentan for treatment of inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: BENEFiT (Bosentan Effects in iNopErable Forms of chronIc Thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension), a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:2127–2134. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghanny S, Crowther M. Treatment with novel oral anticoagulants: indications, efficacy and risks. Curr Opin Hematol. 2013;20:430–436. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328363c170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thistlethwaite PA, Kaneko K, Madani MM, et al. Technique and outcomes of pulmonary endarterectomy surgery. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;14:274–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simonneau G, Delcroix M, Lang I, et al. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. American Thoracic Society; Philadelphia, PA: 2013. Long-term outcome of patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: results of an international prospective registry comparing operated versus non-operated patients; p. A5365. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Auger WR, Fedullo PF. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;30:471–483. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1233316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wittine LM, Auger WR. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2010;12:131–141. doi: 10.1007/s11936-010-0062-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]