Abstract

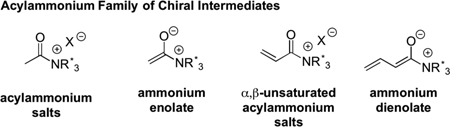

Although acylammonium salts are well-studied, chiral α,β--unsaturated acylammonium salts have received much less attention. While these intermediates are convenient synthons readily available from several commodity unsaturated acids and acid chlorides and possess three reactive sites, their application in organic synthesis has been limited likely due to a lack of appropriate chiral Lewis bases for their generation. In recent years, the utility of chiral, unsaturated acylammonium salts has expanded considerably demonstrating the unique reactivity of this intermediate leading to the development of a diverse array of catalytic, asymmetric transformations including organocascade processes. This Minireview highlights the recent and growing interest in these intermediates which might spark further research into their untapped potential for asymmetric organocascade catalysis. A cursory comparison is made to related unsaturated iminium and acylazolium intermediates.

Keywords: enantioselective, ammonium enolate, organocascade, isothiourea catalysts, cinchona alkaloids, ammonium dienolate

1. Introduction

The seminal work of Wegler in 1932 demonstrated the potential of chiral acylammonium salts for asymmetric acyl transfer processes. Wegler utilized naturally occurring alkaloids (e.g. brucine) as Lewis bases for the kinetic resolution of 1-phenylethanol.1 While enantioselectivities were moderate, these early studies established the potential of chiral acylammonium intermediates. The renewed interest in this area in the1960’s can be attributed to the discovery of dimethyl aminopyridine (DMAP) and related pyridine derivatives and their use as Lewis base catalysts for general acylation reactions by Steglich and Höfle2 as well as Litvinenko and Kirichenko.3 These discoveries ultimately ushered in a new family of chiral intermediates for organocatalysis,4 the acylammonium family, that to date include ammonium enolates, α,β-unsaturated acylammonium salts, and ammonium dienolates. In this Minireview, the current state of the art in the emerging area of unsaturated acylammonium catalysis will be described with a final cursory comparison to related unsaturated iminium and acylazolium intermediates,5 which can be seen as complimentary organocatalytic species. Rather than providing multiple examples of each reaction type, a representative example is presented for brevity.

2. α,β-Unsaturated acylammonium salts

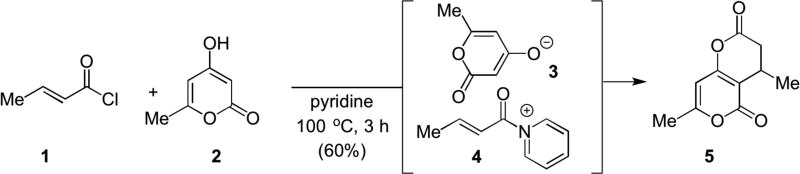

In the 1960s, Yamamura first studied α,β-unsaturated acylammonium salts for Michael-lactonization reactions between α,β-unsaturated acid chlorides and hydroxypyrones employing pyridine as both solvent and a Lewis base.6 Use of crotonyl chloride and hydroxypyrone 2 afforded enol lactone 5 in 60% yield. The authors proposed the intermediacy of an α,β-unsaturated acylammonium salt 4 for the first time, which was formed in situ, from the acid chloride and pyridine (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

The first use of a Lewis base to generate an unsaturated acylammonium salt from an acid chloride leading to Michael-lactonizations.

2.2. Conjugate Additions

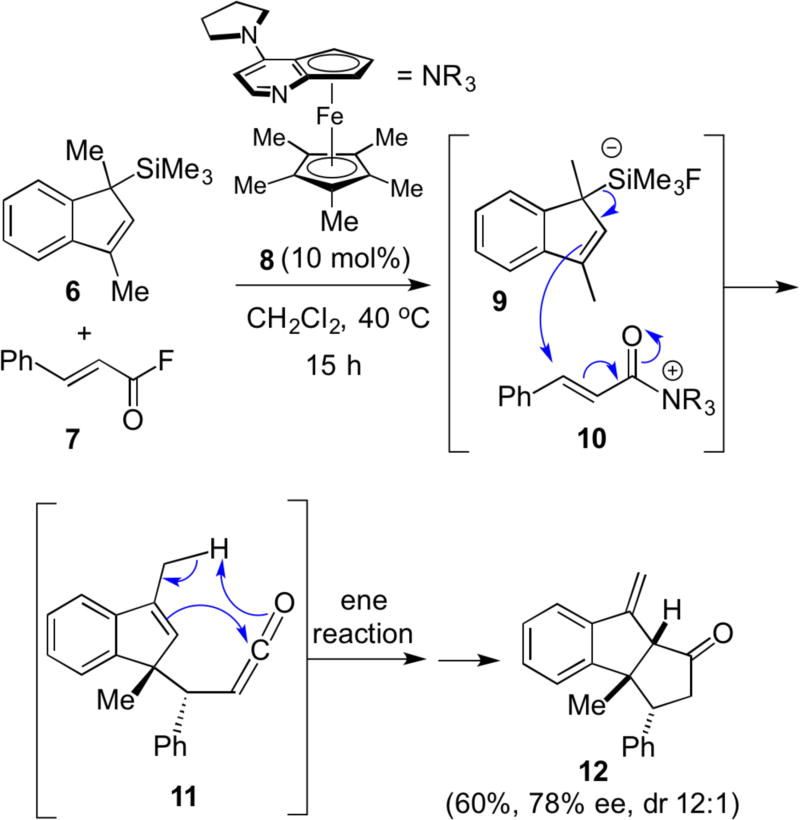

Although the formation of unsaturated acylammonium salts was known since the late 1960s, their utility for asymmetric synthesis was realized only about 10 years ago. A seminal report by Fu in 2006 introduced the first use of chiral α,β-unsaturated acylammonium salts for an organocascade reaction. Addition of the silyl indene 6 led to a net [3+2] annulation to deliver diquinane 12 in 60% yield and 78% ee.7 In this well designed process, the authors proposed that in situ generation of the chiral salt 10 upon reaction of Fu’s chiral pyridine derivative 8 with α,β-unsaturated acid fluoride 7 simultaneously releases fluoride anion leading to activation of the allyl silane and silicate 9. This initiates a cascade involving a stereochemical-setting Sakurai reaction followed by an intramolecular ene reaction with a presumably in situ generated ketene (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

First use of chiral α,β-unsaturated acylammonium salts in a net [3+2] annulation process

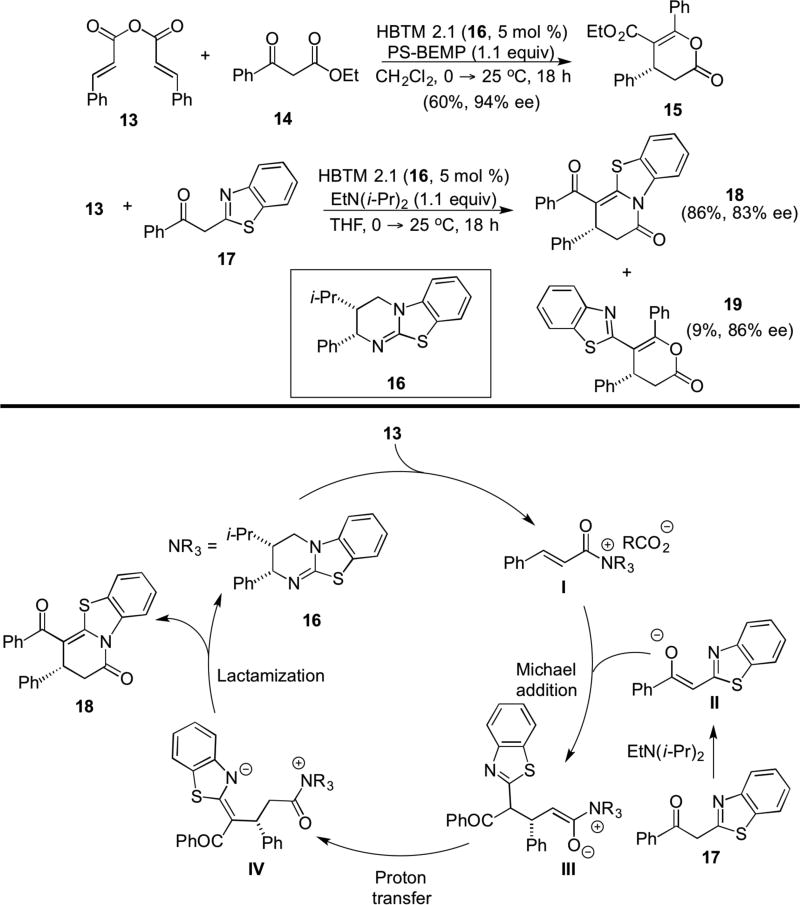

Nearly 7 years after the seminal report by Fu, a series of reports including those from Lupton in 2012 (vide infra, Sect. 2.3)8 and the groups of Smith and Romo in 2013 began to demonstrate the broader utility of chiral, unsaturated acylammonium salts for organocascade asymmetric catalysis. Smith and co-workers employed symmetrical, α,β-unsaturated anhydrides as precursors for unsaturated acylammonium salts and an anionic bis-nucleophile, namely the enolate of a β-ketoester. The modified Birman-Okamoto-type isothiourea catalyst 16 (HBTM 2.1)9 proved optimal as a chiral Lewis base promoter and use of a supported Brønsted base promoted a Michael-enolate-lactonization process with various 1,3-diketones delivering enol lactones (e.g. 15) in up to 94% ee (Scheme 3). The authors proposed that initial formation of an unsaturated acylammonium salt from the anhydride and the modified Birman catalyst, HBTM 2.1 (16), leads to a Michael addition followed by O-acylation by the oxyanion of the resulting enolate sequence affords dihydropyranone 15 in 94% ee.10 This methodology was also applied to the synthesis of dihydropyridones (e.g. 18) through use of aryl thiazole ketones, e.g. 17, with dihydropyranone 19 obtained as a minor product. The formation of 18 was rationalized by invoking a Michael addition of enolate II to unsaturated acyammonium salt I. Subsequent proton transfer generates methylene benzothiazole intermediate IV which undergoes lactamization to afford 18.

Scheme 3.

Smith’s catalytic, asymmetric Michael-lactonization and Michael-lactamization organocascade with symmetrical anhydrides (inset shows catalytic cycle for formation of lactam 18)

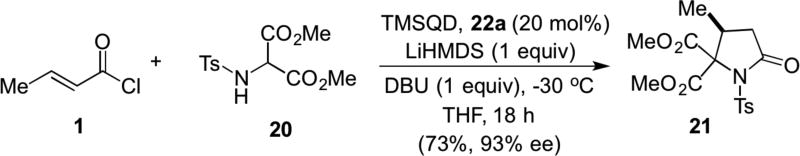

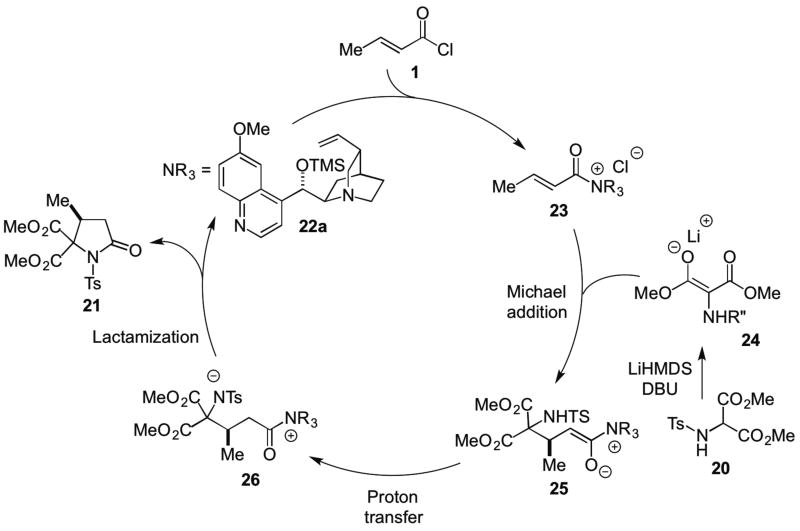

In the same year, the Romo group described two additional organocascade processes involving unsaturated acylammonium salts. Namely, a Michael-proton transfer-lactamization and an Michael aldol-lactonization organocascade leading to γ- and δ-lactams and bi- and tri-cyclic-β-lactones, respectively. Addition of an amino malonate as a bis-nucleophile to an unsaturated acylammonium salt generated in situ from commodity acid chlorides using a cinchona alkaloid as Lewis base catalyst, TMSQD (22a). The reaction involved α-deprotonation of aminomalonates e.g. 20 in THF followed by addition of DBU and TMSQD with slow addition of β-methyl acryloyl chloride (1) at low temperatures in THF (Scheme 4). This delivered substituted pyrrolidinone 21 in 73% yield and 93% ee.11 The utility of this process to access both γ- and δ-lactams stems from the readily available starting materials including the use of commodity acid chlorides.

Scheme 4.

Romo’s Michael-proton transfer-lactamization organocascade with commodity acid chlorides.

The proposed catalytic cycle involves kinetic generation of a malonate enolate 24 with LiHMDS which undergoes a Michael addition with the unsaturated acylammonium salt 23, derived from acid chloride 1 and TMSQD (22a) to produce the intermediate ammonium enolate 25. Subsequent proton transfer generates the zwitterionic intermediate 26 enabling the resulting nitrogen anion to undergo lactamization with the pendant acylammonium to deliver pyrrolidinone 21 (Scheme 5). The authors determined that a Li counterion versus Na, through use of NaHMDS, was crucial for high enantioselectivity. This was proposed to be a result of tighter coordination of the enolate oxygen atom and the acylammonium carbonyl with the Li cation in the transition state arrangement for the initial Michael addition.

Scheme 5.

Proposed catalytic cycle for the Michael-Proton Transfer-Lactamization organocascade

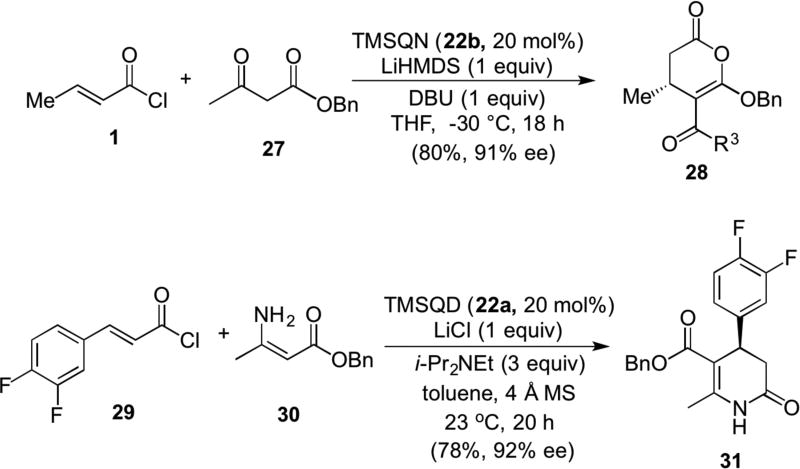

A mechanistically related reaction involving ketoesters (e.g. 27) as bis-nucleophiles, reminiscent of work by Smith with the exception that acid chlorides were employed (e.g. 1), provided enol lactones (e.g. 28) through a presumed Michael-proton transfer-lactonization cascade with unsaturated acylammonium salts (Scheme 6). In this case, the cinchona alkaloid derivative TMSQN 22b was the optimal Lewis base catalyst and a similar cascade with enamide 30 as a bis-nuclelophile afforded dihydropyridone 31, a known precursor to an α1a-adrenergic receptor antagonist.12 A described 13C NMR study suggested that only mild activation is induced upon formation of unsaturated acylammonium salt intermediates, however formation of a bulky ammonium may simply preclude 1,2-addition.

Scheme 6.

Romo’s Michael-proton transfer-lactonization/lactamization organocascade with commodity acid chlorides (e.g. 1)

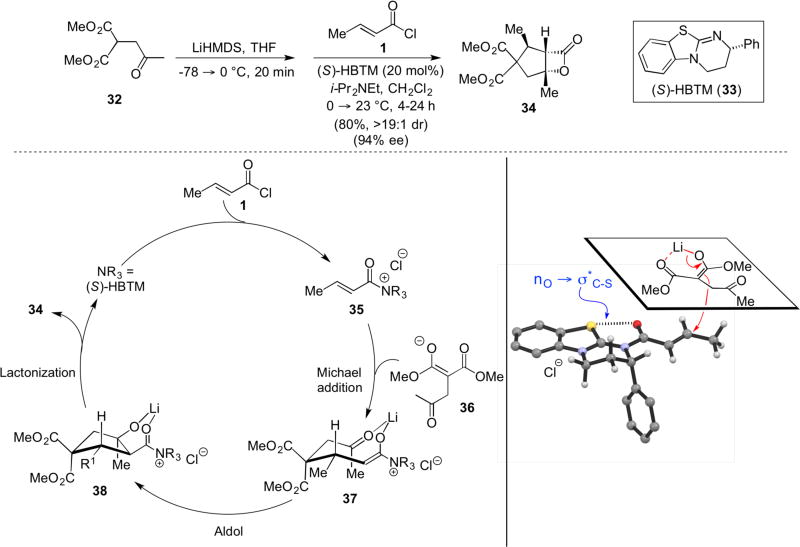

For more than a decade, the Romo group has employed chiral acylammonium enolates for the synthesis of β-lactones though nucleophile(Lewis bases)-catalyzed aldol-lactonization13 Most recently the use of ketoacids provided facile access to both bi- and tricylic β-lactones through activation of acid substrates with tosyl chloride enabling a nucleophile-catalyzed aldol-lactonization (NCAL).14 Building from these previous studies, an organocascade process was designed to make use of unsaturated acylammonium salts, again derived from commodity acid chlorides, for the in situ generation of ammonium enolates through an initial Michael addition. A subsequent aldol-lactonization sequence led to the rapid construction of highly substituted cyclopentanes bearing fused β-lactones (Scheme 7). The cyclopentyl-fused, β-lactones (e.g. 34) were obtained in high enantiomeric purity and good yields using Birman’s homobenzotetramisole (HBTM) catalyst with ketomalonates and commodity acid chlorides.15 Importantly, this organocascade highlighted the triple reactivity of the unsaturated acylammonium salt intermediate in its ability to participate first as an electrophile, then a nucleophile through the ammonium enolate, and finally as an electrophile through the acylammonium intermediate. The proposed organocascade involves generation of ammonium enolate 37 by the Michael addition of malonate anion 36 to the α,β-unsaturated acylammonium chloride 35. The incipient ammonium enolate then undergoes an aldol reaction with the pendant ketone followed by β-lactonization to deliver bicyclic β-lactone 34 with high enantio- and diastereoselectivity. A model was proposed to rationalize the stereochemical outcome premised on previous proposals by Birman for acylammonium intermediates derived from related isothioureas16 in which he invoked a rare no → σ*C-S interaction.17 This interaction assists in controlling the conformation of the unsaturated acylammonium salt and in conjunction with the expected s-trans conformation leads to the overall structure shown. The pseudoaxial phenyl ring of the boat-like tetrahydropyrimidine thus blocks the α-face directing the initial Michael addition to the β-face. The remaining stereocenters were proposed to be dictated through diastereoselective aldol-lactonization governed by the cyclic, chair-like transition state arrangement 37.

Scheme 7.

Romo’s nucleophile (Lewis base)-catalyzed Michael aldol-lactonization (NCMAL) organocascade, proposed catalytic cycle, and rationalization of absolute stereochemistry.

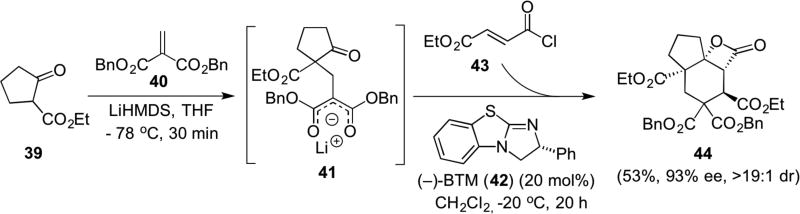

The Romo group combined the power of the NCMAL process with an initial Michael reaction to develop a multicomponent reaction that also features a kinetic resolution. The initial racemic, Michael adduct 41 generated between the enolate of β-ketoester 39 and methylenemalonate 40 engages in a NCMAL reaction with unsaturated acylammonium salt derived from acid chloride 43. This results in a three component organocascade affording the complex cyclohexyl fused-tricyclic β-lactone 44 with four contiguous stereocentres with both high enantio- and diastereoselectivity (Scheme 8).15

Scheme 8.

The first multicomponent organocascade involving unsaturated acylammonium salts also featuring a kinetic resolution of in situ generated racemic malonate enolate 41.

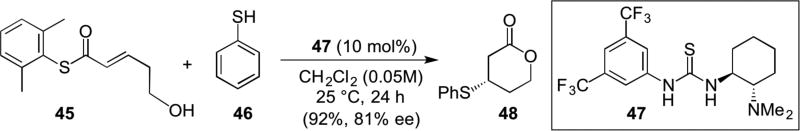

The breadth of nucleophiles capable of engaging in a Michael reaction with α,β-unsaturated acylammonium salts was extended to sulphur by Matsubara.18 In this case, bulky thioesters (e.g. 45) served as precursors to unsaturated acylammonium salts with bi-functional thiourea catalyst 47 serving as both a Lewis base and H-bond donor (Scheme 9). Thiophenol (46) undergoes a thia-Michael addition and subsequent lactonization ensues with the pendant alcohol delivering β-mercaptolactones (e.g. 48). The enantioselectivities observed suggest that a background thia-Michael of thiophenol with thioester 45 is slow relative to the catalysed process proceeding through the unsaturated acylammonium salt.

Scheme 9.

Matsubara’s isothiourea catalyzed thia-Michael lactonization organocascade employing thioester substrates (e.g. 45).

Building on their previous studies, Matsubara recently reported the asymmetric synthesis of benzothiazepines (e.g. 51) from tosylated aminothiophenols (e.g. 49) and mixed anhydrides (e.g. 50) mediated by (−)-BTM (42) (Scheme 10). The thia-Michael showed complete regioselectivity with respect to the bis-nucleophile 49 (S vs. N) reflecting the soft nature of sulfur as a nucleophile.19 Critical to the success of this process was the use of mixed anhydrides 50 with bulky alkyl substituents (e.g. i-Pr).

Scheme 10.

Matsubara’s thia-Michael-proton transfer-lactamization organocascade delivering benzothiazepines (e.g. 51).

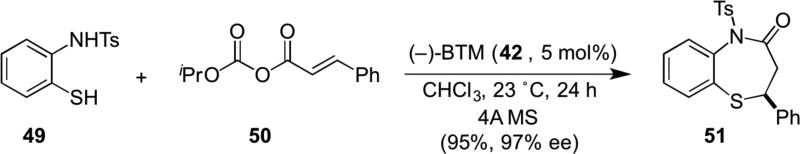

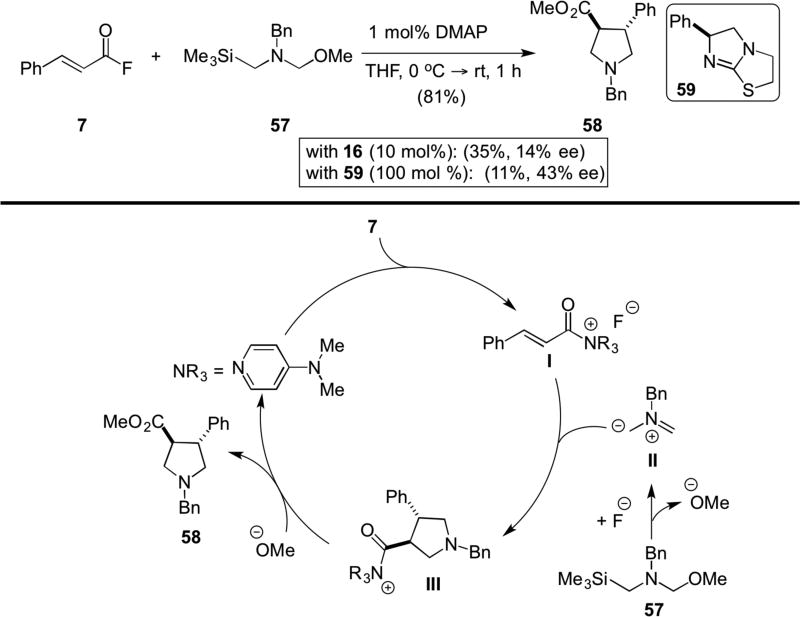

In an extension of their previous studies and early studies by Yamamura, the Romo group reported the synthesis of polycyclic dihydropyranones from commodity acid chlorides and cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyls with N,N-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) as Lewis base promoter (Scheme 11).20 The use of excess (2.0 equiv) cyclic-β-diketones and prolonged reaction times were critical for optimal yields and this was attributed to the reversible formation of an enol ester by-product 56 formed through O-acylation which was shown to re-enter the catalytic cycle but only slowly through cross-over experiments. Under optimized conditions, crotonyl chloride 1 and hydroxycoumarin 52 with DMAP as Lewis base promoter, provided enol-lactone 53 in good yield. Amino ester 54 also participated under similar conditions to deliver a dihydropyridone 55 previously used in the synthesis of dielsine. Comparative 13C NMR studies were also reported to determine the extent of β-carbon activation, if any, upon formation of acylammonium salt intermediates. The authors concluded that the principal effect of acylammonium formation may be slowing the rate of 1,2-addition rather than significant activation of the β-carbon which in this case would be solely through inductive effects propagated through the carbon framework.

Scheme 11.

Romo’s synthesis of polycyclic dihydropyranones (e.g. 53) and a dihydropyridone 55 through a Michael-enol lactonization/enamino lactamization organocascade. Comparative 13C NMR studies of crotonyl chloride and derived unsaturated acylammonium intermediates.

2.3. Cycloadditions

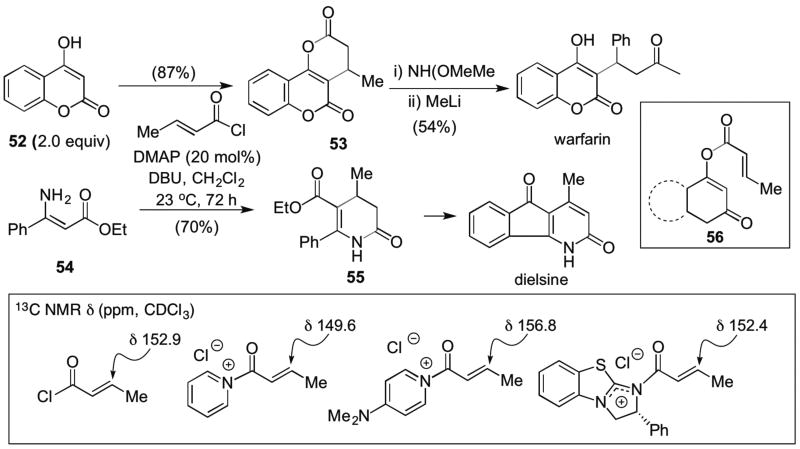

Following the report by Fu,7 the Lupton lab reported the first 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions of in situ generated, unstabilised azomethine ylides with unsaturated acylammonium salts.8 These were derived from acid fluorides (e.g. 7) and isothiourea Lewis bases (Scheme 12). Generation of fluoride ion upon acylammonium salt generation affords the 1,3-dipole II in situ from 57 which then engages in a 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition leading to adduct III followed by esterification to deliver pyrrolidines 58. The authors also studied enantioselective versions with isothiourea catalysts. After extensive mechanistic investigations, the authors concluded that the cycloaddition preferentially occurs with acyl fluoride 7 and therefore only low enantioselectivity was achieved.

Scheme 12.

Lupton’s 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of an unsaturated acylammonium salt with an azomethine ylide generated in situ from 57.

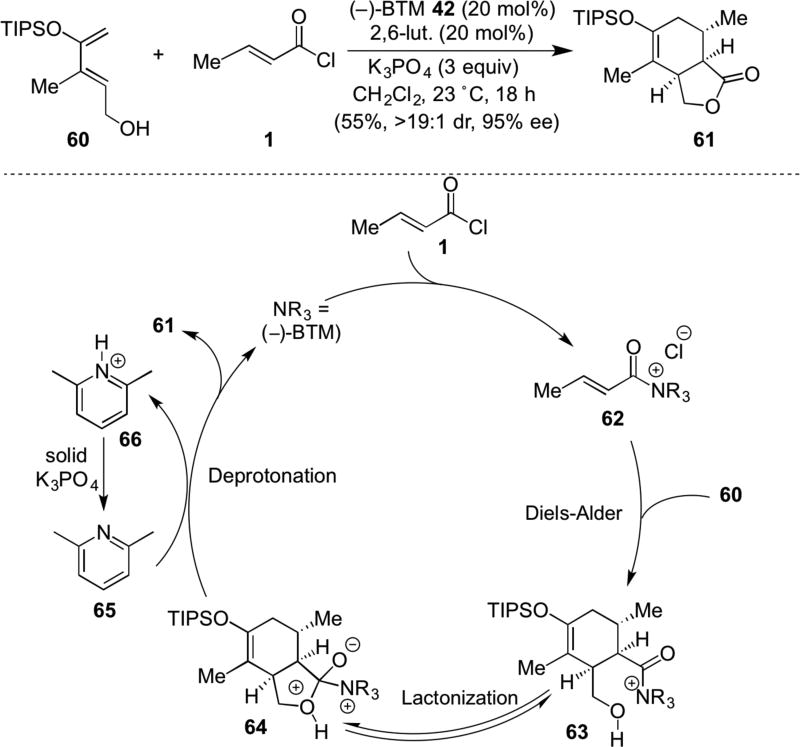

The utility of chiral α,β-unsaturated acylammonium salts as dienophiles for the venerable Diels-Alder reaction was studied by the Romo group leading to development of an asymmetric Diels-Alder lactonization (DAL) organocascade (Scheme 13).21 Use of O-silylated dienes bearing pendant alcohols (e.g. 60) with commodity acid chlorides (e.g. 1) led to versatile bicyclic γ-lactones (e.g. 61) with high levels of diastereo- and enantiocontrol with (−)-BTM as Lewis base promoter. Use of a shuttle base combination of 2,6-lutidine 65 and K3PO422 was essential for high endo/exo selectivity by presumably reducing a reversible, initial D-A process prior to lactonization. The proposed catalytic cycle leading to an enantioselective DAL necessarily involves initial intermolecular DA between diene 60 and unsaturated acylammonium salt 62 delivering the cycloadduct 61 which undergoes terminating lactonization through deprotonation. The importance of the deprotonation step of intermediate 64 was reflected in greatly differing yields and diastereoselectivities based on Brönsted base employed. Computational studies by the Tantillo group provided further support for the previously described preferred conformation of the unsaturated acylammonium isothiourea adduct (cf. Scheme 7) rationalizing the enantioselectivity. Comparative energy calculations rationalized the high endo selectivity of the DAL process and the slower direct, background D-A reaction with acid chlorides.

Scheme 13.

Romo’s Diels-Alder-lactonization (DAL) organocascade employing novel chiral unsaturated acylammonium dienophiles with proposed catalytic cycle.

In addition, the greater utility of the terminating acylammonium lactonization step was realized through development of both stereodivergent and kinetic resolutions through the DAL process. Use of racemic dienes (e.g. 67) bearing a pendant, secondary alcohol delivered readily separable diastereomeric mixtures of enantiopure tricyclic γ-lactones 68a and 68b, previously employed as intermediates toward compactin23a and forskolin.23b (Scheme 14).21

Scheme 14.

Stereodivergent DAL organocascades employing racemic diene 67 delivering complex, separable diastereomeric cycloadducts 68a,b.

2.4. Unsaturated acylammonium-ammonium dienolate interplay

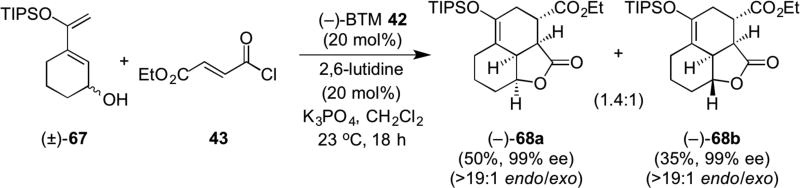

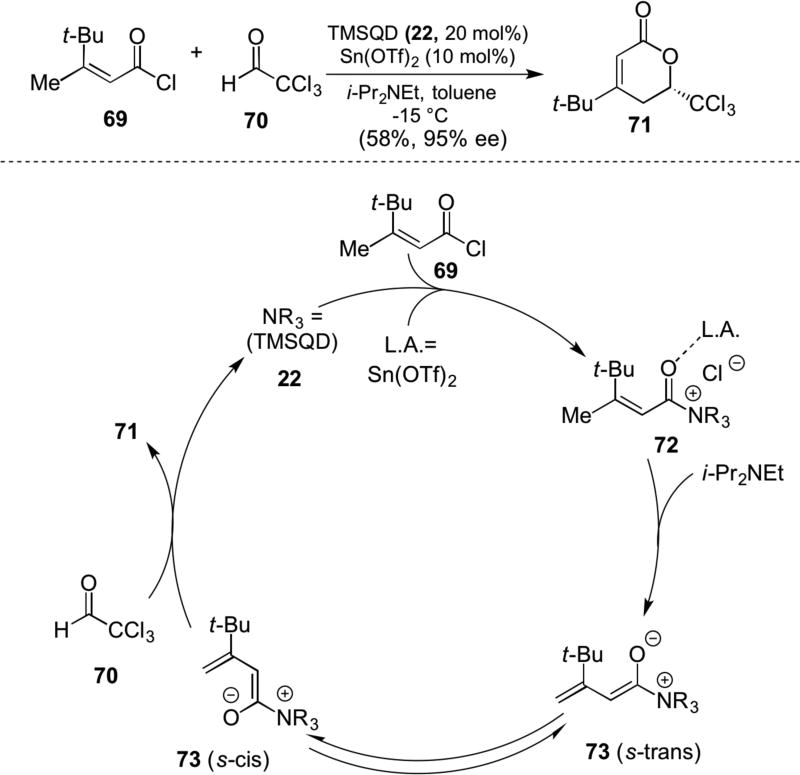

A new concept of converting unsaturated acylammonium salts into nucleophilic species, namely ammonium dienolates, was introduced by Peters in 2007.24 The chiral dienolate 73 was generated by deprotonation of the unsaturated acylammonium species 72 derived from acid chloride 69 and TMSQD (22a) through the action of Sn(OTf)2 and Hünig’s base. This zwitterionic dienolate undergoes a net 4+2 cycloaddition, presumably through the s-cis conformation, with chloral 70 delivering δ-lactone 71 in good yields and high enantiopurity. (Scheme 15).

Scheme 15.

Peters’ ammonium dienolate generation and net [4+2] cycloaddition with chloral (70) with postulated catalytic cycle.

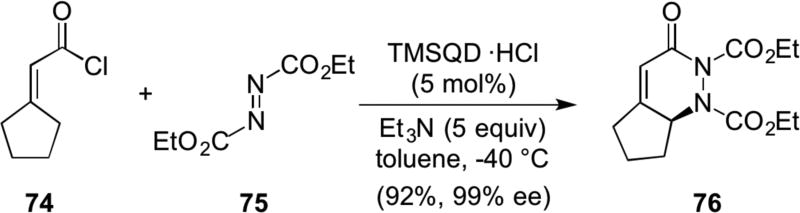

Recently Ye, extended the utility of ammonium dienolates to overall γ-amination of α,β-unsaturated acid chlorides catalyzed by TMSQD (22a).25 For example, generation of ammonium dienolate, from acid chloride 74 and TMSQD led to a [4+2] cyclization with diethy azodicarboxylate 75, to provide dihydropyridazinone 76 in good yields with high enantioselectivity (Scheme 16). Reductive ring opening of the resultant dihydropyridazinone generated γ-amino acids. Subsequently, both Peters and Ye reported extensions of this concept with aromatic aldehydes,26 isatilidines27 and N-Boc imines28 as reaction partners with ammonium dienolates.

Scheme 16.

Ye’s [4+2] cycloaddition of ammonium dienolates and azo compounds leading to net γ-amination of unsaturated acid chlorides.

3. Complimentarity to α,β-unsaturated iminium and acylazolium catalysis

To place the utility of unsaturated acylammonium salts in context of related intermediates, namely iminium and N-heterocyclic acylazolium intermediates, early and analogous reactions employing these latter species are briefly presented. A cursory overview of analogies and differences will be made between these related but distinct organocatalytic intermediates both in terms of their generation and reactivity.

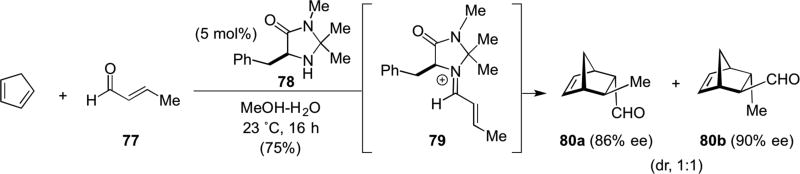

3.1. Diels-Alder cycloadditions through α,β-unsaturated iminium catalysis

The discovery of imidazolidinone-catalyzed Diels-Alder reactions of iminium salts with cyclopentadiene by MacMillan ushered in a new mode of asymmetric functionalization of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes.29 The chiral iminium ion 79 formed between imidazolidinone 78 and enal 77 underwent enantioselective Diels-Alder cycloaddition with cyclopentadiene to afford endo-80a and exo-80b cycloadducts (Scheme 17).

Scheme 17.

Macmillan’s Diels-Alder cycloaddition employing α,β-unsaturated iminium catalysis.

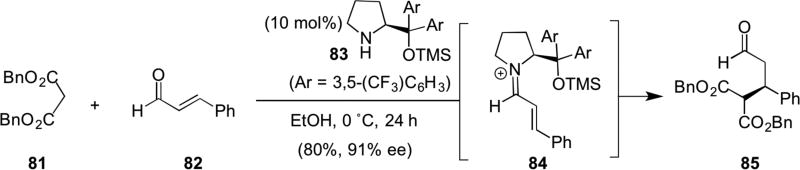

3.2. Michael additions through α,β-unsaturated iminium catalysis

The first Michael reaction with a chiral, α,β-unsaturated iminium species was reported by Jørgensen in 2006.30 Conjugate addition of dibenzyl malonate (81) to iminium 84 derived from cinnamaldehyde (82) and the proline-derived catalyst 83 provided optically active aldehyde 85 (Scheme 18).

Scheme 18.

Jørgensen’s Michael addition employing α,β-unsaturated iminium catalysis.

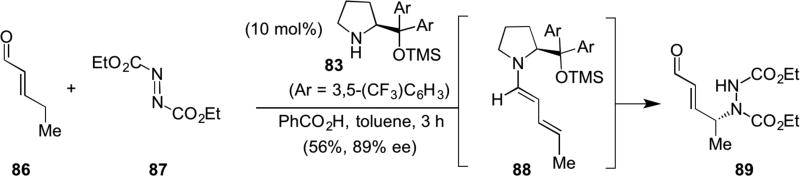

3.3. Umpolung reactivity through dienamine formation

Another reaction manifold for unsaturated iminium species was discovered by Jørgensen’s lab.31 While conducting mechanistic studies, they observed the formation of an electron-rich dienamine intermediate 88, presumably formed by γ-deprotonation of the unsaturated iminium species. Nucleophilic addition to the azo compound, diethylazodicarboxylate (DEAD, 87), provided evidence for this intermediate through generation of the corresponding γ-aminated enal with high enantio- and regioselectivity using the same prolinol-derived catalyst 83 (Scheme 19). Conceptually this can be viewed as an umpolung reactivity of electrophilic enals.

Scheme 19.

Jørgensen’s Michael addition employing iminium catalysis.

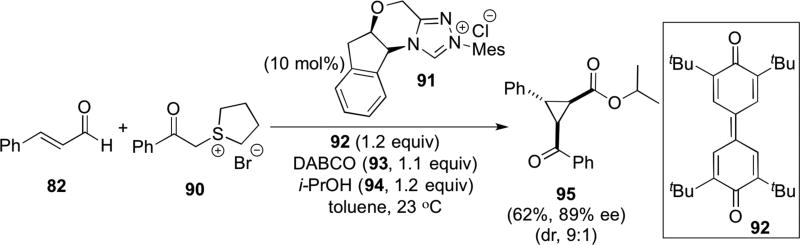

3.3. Cyclopropanation-esterification through α,β-unsaturated acylazolium catalysis

The utility of unsaturated acylazolium intermediates continues to expand and readers are directed to recent reviews in this area.32 Only one example is provided here which demonstrates close analogy to several reactions described herein for unsaturated acylammonium salts;; namely, the triple reactivity of these related intermediates. Studer reported a cyclopropanation proposed to proceed through initial Michael addition of the sulfonium ylide generated from sulfonium salt 90 to the unsaturated acylazolium derived from cinnamaldehyde (82) and triazolium salt 91. Subsequent ring closure through enolate displacement of the sulfonium species and final esterification by i-PrOH present in the reaction mixture provided cyclopropyl ester 95. As might be anticipated, a competing pathway is direct esterification of the intermediate acylazolium leading to ester by-products (e.g. cinnamic acid isopropyl ester). An external oxidant 92 is required to oxidize to the unsaturated acylazolium, however one advantage is the mild reaction conditions (23 °C).33

An interesting contrasting mechanistic pathway first reported by Bode for reactions involving unsaturated acylazolium intermediates invokes nucleophilic addition to the acylazolium carbonyl followed by [3,3] Claisen rearrangement.34

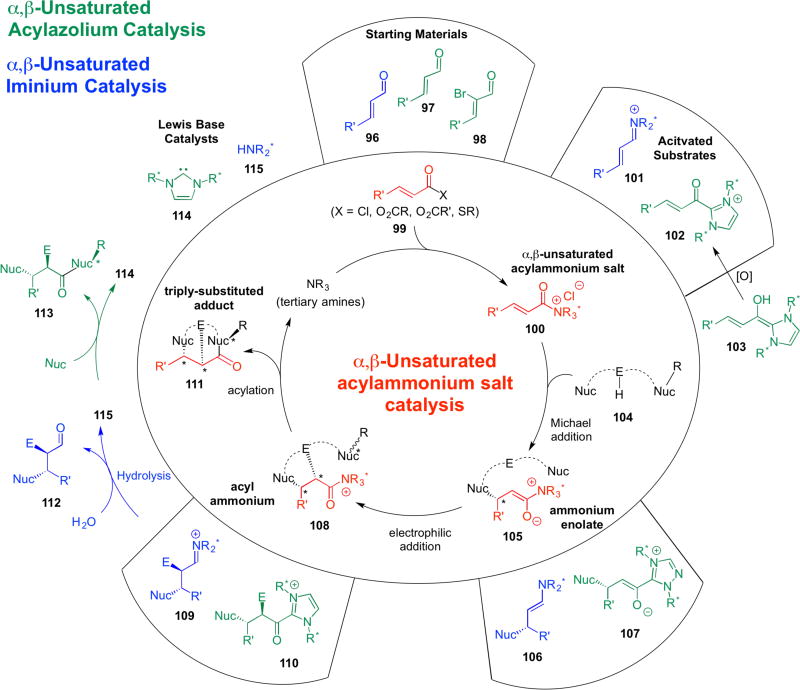

3.4. Comparing and contrasting unsaturated acylammonium catalysis with iminium and acylazolium catalysis

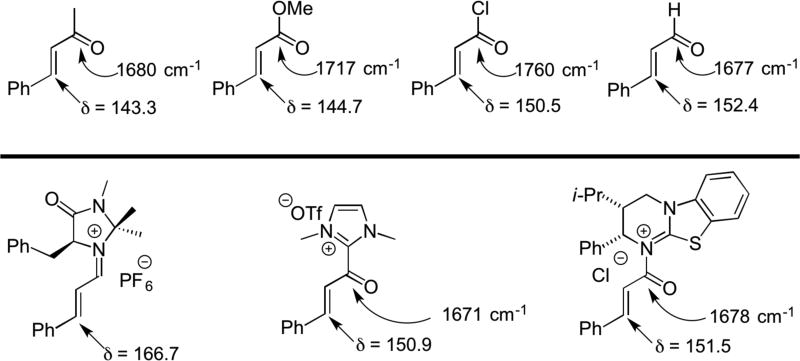

We offer a cursory comparison of these three related but distinct species contrasting their respective catalytic cycles (Scheme 21) and limited spectral data (Scheme 22) that has been reported to date that may reflect differences in their reactivity. Readers are also directed to numerous reports describing the reactivity of α,β-unsaturated iminium35 and α,β-unsaturated acylazolium species32 which point to their differing reactivity.

Scheme 21.

Contrasting the starting materials, intermediates, and catalytic cycles involved in α,β-unsaturated acylammonium catalysis (center circle) with acylazolium (green) and iminium (blue) catalysis.

Scheme 22.

Comparison of C=O IR stretching frequencies and 13C chemical shifts of β-carbons for unsaturated β-phenyl ketones, esters, acid chlorides, and aldehydes to α,β-unsaturared iminium, acylazolium, and acylammonium salts.

With respect to generation of these intermediates, commodity α,β-unsaturated acid chlorides, anhydrides, and thioesters (cf. 99) have been employed as precursors for unsaturated acylammonium salts 100, whereas acylazoliums are typically prepared from unsaturated aldehydes 97 but require oxidation of the enol homoenolate to the acylazolium (103→102). Recently, the use of ynals,36 α-bromo aldehydes 98,37 α,β-unsaturated acyl fluorides,38 and p-nitrophenol esters39 as starting materials is enabling direct generation of α,β-unsaturated acylazolium intermediates.

Analogous intermediates are seen throughout the catalytic cycles to the ammonium enolate 105 (cf. 106, 107) and the acylammonium (cf. 109, 110). When considering the requirements for catalyst turnover during the catalytic cycle, a closer analogy can be made between unsaturated acylazolium and acylammonium organocascades. With both of these intermediates, there is a requirement for a termination step involving nucleophilic substitution of the acylazolium or acylammonium intermediate in an intra- or intermolecular process (108→111). The required termination step enables generation of an additional ring in this final step of the organocascade. As described above with Diels-Alder lactonizations, this has been used to great advantage for introduction of an additional stereocenter through stereodivergent cycloadditions with racemic dienes bearing pendant secondary alcohols (cf. Scheme 14). This strategy has not yet been studied in the context of acylazolium intermediates. In the case of iminium catalysis, hydrolysis is required for catalyst turnover pointing to a practical advantage of non-stringent anhydrous conditions. The ability to functionalize all three carbons of both unsaturated acylammonium and acylazolium species also renders these intermediates similar (cf. Scheme 20). In addition to intermolecular reactions leading to substituted acid derivatives, this enables the use of tethered nucleophile-electrophile-nucleophile (cf. 104) combinations to generate polycyclic carbocycles and heterocycles with multiple stereocenters (cf. 111).

Scheme 20.

Studer’s α,β-unsaturated acylazolium mediated cyclopropanation-esterification cascade.

A comparison of C=O IR stretching frequencies shows a correlation between α,β-usaturated aldehydes (1677 cm−1) and both acylazolium (1671 cm−1) and acylammonium salts (1678 cm−1) (Scheme 22). These data suggest that activation of acyl carbons by N-heterocyclic carbene and tertiary amine catalysts may impart an activation comparable to an aldehyde. Comparison of the 13C chemical shifts of the β-carbons of these species also suggests, not surprisingly, that through resonance effects of iminium activation (δ 166.7) is significant compared to both acylammonium (δ 151.5) and acylazolium (δ 150.9) species which activate only inductively.

4. Conclusion and outlook

The preceding account demonstrates that chiral, α,β-unsaturated acylammonium salts are highly versatile three carbon synthons with unique and divergent reactivity. These intermediates are readily derived from the reaction of commodity acid chlorides, or more generally from in situ activated carboxylic acids, with both isothiourea and cinchona alkaloid Lewis bases. This provides a highly practical strategy for the expeditious synthesis of optically active polycyclic carbocycles and heterocycles with correspondence to natural products and drugs. Further applications of these intermediates would appear to be limited only by the range of nucleophiles and electrophiles with sufficient and matched reactivity. These intermediates are complimentary to reactions developed involving iminium and acylazolium catalysis, with greater analogy to the latter class of intermediates. Athough unsaturated acylammonium salts were first discovered nearly 40 years ago, synthetic chemists have only recently begun to tap into their utility for asymmetric catalysis and particularly organocascade catalysis. Further developments in this area will undoubtedly reveal further hidden potential in this very simple yet highly practical and powerful activation mode for unsaturated carboxylic acids.

Acknowledgments

The methodology developed in the Romo group and presented here was supported by NSF (CHE-1112397), the Welch Foundation (AA-1280), and partially by NIH (R37 GM052964).

References

- 1.Wegler R. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1932;498:62–76. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Steglich W, Höfle G. Angew. Chem. 1969;81:1001. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.1969, 8, 981; [Google Scholar]; b) Höfle G, Steglich W. Synthesis. 1972:619–621. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litvinenko LM, Kirichenko AI. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR. 1967;176:197–200. [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) France S, Guerin DJ, Miller SJ, Lectka T. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2985–3012. doi: 10.1021/cr020061a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gaunt MJ, Johansson CCC. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:5596–5605. doi: 10.1021/cr0683764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Müller CE, Schreiner PR. Angew. Chem. 2011;123:6136–6167. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2011, 50, 6012 – 6042. [Google Scholar]; (d) Abbasov ME, Romo D. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014;31:1318–1327. doi: 10.1039/c4np00025k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Mukherjee S, Yang JW, Hoffmann S, List B. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:5471–5569. doi: 10.1021/cr0684016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Doyle AG, Jacobsen EN. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:5713–5743. doi: 10.1021/cr068373r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) MacMillan DWC. Nature. 2008;455:304–308. doi: 10.1038/nature07367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Barbas C., III Angew. Chem. 2008;120:44–50. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2008, 47, 42 – 47; [Google Scholar]; e) Grossmann A, Enders D. Angew. Chem. 2012;124:320–332. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2012, 51, 314 – 325. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kato K, Shizuri Y, Hirata Y, Yamamura S. Chem. Commun. 1968:324–325. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bappert E, Müller P, Fu GC. Chem. Commun. 2006:2604–2606. doi: 10.1039/b603172b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pandiancherri S, Ryan SJ, Lupton DW. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:7903–7911. doi: 10.1039/c2ob26047f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Birman VB, Li X. Org. Lett. 2008;6:1115–1118. doi: 10.1021/ol703119n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kobayashi M, Okamoto S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:4347–4350. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson E, Fallan C, Simal C, Slawin A, Smith AD. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:2193–2200. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vellalath S, Van KN, Romo D. Angew. Chem. 2013;125:13933–13938. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306050. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2013, 52, 13688 – 13693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nantermet PG, Barrow JC, Selnick HG, Homnick CF, Freidinger RM, Chang RSL, O’Malley SS, Reiss DR, Broten TP, Ransom RW, Pettibone DJ, Olah T, Forray C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000;10:1625–1628. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00696-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Cortez GS, Tennyson R, Romo D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:7945–7946. doi: 10.1021/ja016134+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nguyen H, Ma G, Fremgen T, Gladysheva T, Romo D. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:2–12. doi: 10.1021/jo101638r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Liu G, Shirley ME, Romo D. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:2496–2500. doi: 10.1021/jo202252y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leverett CA, Purohit VC, Romo D. Angew. Chem. 2010;122:9669–9673. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004671. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2010, 49, 9479–9483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu G, Shirley ME, Van KN, McFarlin RL, Romo D. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:1049–1057. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birman VB, Li X, Han Z. Org. Lett. 2007;9:37–40. doi: 10.1021/ol0623419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Nagao Y, Hirata T, Goto S, Sano S, Kakehi A, Iizuka K, Shiro M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:3104. [Google Scholar]; b) Beno BR, Yeung K-S, Bartberger MD, Pennington LD, Meanwell NA. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:4383–4438. doi: 10.1021/jm501853m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukata Y, Okamura T, Asano K, Matsubara S. Org. Lett. 2014;16:2184–2187. doi: 10.1021/ol500637x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukata Y, Asano K, Matsubara S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:5320–5323. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b02537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vellalath S, Van KN, Romo D. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015;56:3647–3652. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbasov ME, Hudson BM, Tantillo DJ, Romo D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:4492–4495. doi: 10.1021/ja501005g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hafez AM, Taggi AE, Wack H, Esterbrook J, Lectka T. Org. Lett. 2001;3:2049. doi: 10.1021/ol0160147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.a) Takatori K, Hasegawa K, Narai S, Kajiwara M. Heterocycles. 1996;42:525. [Google Scholar]; b) Calvo D, Port M, Delpech B, Lett R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:1023. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tiseni PS, Peters R. Angew. Chem. 2007;119:5419–5422. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700859. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2007, 46, 5325–5328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen L-T, Sun L-H, Ye S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:15894–15897. doi: 10.1021/ja206819y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tiseni PS, Peters R. Org. Lett. 2008;10:2019–2022. doi: 10.1021/ol800742d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen L-T, Jia W-Q, Ye S. Angew. Chem. 2013;125:613–616. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207405. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2013, 52, 585–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jia W-Q, Chen X-Y, Sun L-H, Ye S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014;12:2167–2171. doi: 10.1039/c4ob00114a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahrendt KA, Borths CJ, MacMillan DWC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:4243–4244. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brandau S, Landa A, Franzèn J, Marigo M, Jørgensen KA. Angew. Chem. 2006;118:4411–4415. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2006, 45, 4305–4309. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertelsen S, Marigo M, Brandes S, Dinèr P, Jørgensen KA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:12973–12980. doi: 10.1021/ja064637f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.For reviews of acylazolium chemistry including applications of α,β unsaturated acylazolium intermediates, see: Mahatthananchai J, Bode JW. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:696–707. doi: 10.1021/ar400239v.Flanigan DM, Romanov-Michadilidis F, White NA, Rovis T. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:9307–9387. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00060.

- 33.Biswas A, Sarkar SD, Tebben L, Studer A. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:5190–5192. doi: 10.1039/c2cc31501g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahatthananchai J, Zheng P, Bode JW. Angew. Chem. 2011;123:1711. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005352. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2011, 50, 1673–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.For a review of iminium catalysis including applications of α,β-unsaturated iminium intermediates, see: Erkkila A, Majander I, Pihko PM. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;107:5416–5470. doi: 10.1021/cr068388p.

- 36.Zeitler K. Org. Lett. 2006;8:637–640. doi: 10.1021/ol052826h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun F-G, Sun L-H, Ye S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011;353:3134–3138.For a recent example, see: Mondal S, Yetra SR, Patra A, Kunte SS, Gonnade RG, Biju AT. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:14539–14542. doi: 10.1039/c4cc07433e.

- 38.Ryan SJ, Candish L, Lupton DW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:4694–4697. doi: 10.1021/ja111067j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng J, Huang Z, Chi YR. Angew. Chem. 2013;125:8754–8758. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2013, 52, 8592–8596. [Google Scholar]