Abstract

This paper describes the rationale, design, and methods of the Treatment for Anxiety in Autism Spectrum Disorders study, a three-site randomized controlled trial investigating the relative efficacy of a modular CBT protocol for anxiety in ASD (Behavioral Interventions for Anxiety in Children with Autism) versus standard CBT for pediatric anxiety (the Coping Cat program) and a treatment-as-usual control. The trial is distinct in its scope, its direct comparison of active treatments for anxiety in ASD, and its comprehensive approach to assessing anxiety difficulties in youth with ASD. The trial will evaluate the relative benefits of CBT for children with ASD and investigate potential moderators (ASD severity, anxiety presentation, comorbidity) and mediators of treatment response, essential steps for future dissemination and implementation.

Keywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder, Anxiety Disorder, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, Randomized Controlled Trial

Introduction

Rationale, Design and Methods

The Treatment of Anxiety in Autism Spectrum Disorder (TAASD) study is a National Institute of Health funded, multi-site, randomized controlled trail (RCT) to evaluate the efficacy of standard relative to modular cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for anxiety in cognitively-able children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). We describe the rationale, methodological choices, challenges and design of the TAASD study.

Anxiety in Youth with ASD

Affecting as many as 1 in 68 children in the United States, ASD is an increasingly common childhood neurobiological condition [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2009]. Anxiety disorders are prevalent and impairing among youth with ASD, making them important candidates for services (Volkmar and Klin 2000; White et al. 2009). A recent meta-analysis found that as many as 40% of youth with ASD have one or more diagnosable anxiety disorders, the most frequent being specific phobia (29.8%), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD; 17.4%) and social anxiety disorder (16.6%; van Steensel et al. 2011). As in youth without ASD, co-occurrence of anxiety disorders is common (Simonoff et al. 2008). Prevalence estimates vary according to study recruitment, sampling and assessment methods (i.e., questionnaire versus interview, informant versus self-report), and range from 11–84% across studies (Van Steensel et al. 2011; White et al. 2009). Further, research suggests up to 46% of children with ASD experience qualitatively varied fears and worries, such as fears of change, novelty, or unusual specific stimuli (e.g., men with beards, toilets) that do not fit neatly into traditional diagnostic categories (e.g., OCD, specific phobia, social, separation and generalized anxiety disorder) and yet are associated with significant distress and impairment (Kerns et al. 2014; Mayes et al. 2013). Interfering anxiety is associated with a number of physical and psychosocial symptoms in children with ASD, including gastrointestinal illness, self-injurious behavior, depressive symptoms, enhanced family stress, and reduced social responsiveness and initiation (Bellini 2004; Mazurek et al. 2013; Kelly et al. 2008; Kerns et al. 2014; Sukhodolsky et al. 2008).

The relationship between anxiety and core ASD symptoms is complex. Symptoms of anxiety and OCD can be difficult to disentangle from core features of ASD due to symptom overlap (e.g., social avoidance, compulsive behavior), the varied focus of anxiety concerns (e.g., fears of novelty/change, which are often resisted in ASD) and the communication and emotion recognition deficits associated with ASD. Moreover, anxiety may influence the severity and nature of ASD symptoms and vice versa (Kerns and Kendall 2012; Wood and Gadow 2010). Characteristics of ASD, such as executive functioning deficits, cognitive rigidity, and sensory differences, may enhance risk for anxiety. In turn, anxiety symptoms may reduce social and adaptive functioning as well as aggravate repetitive and restricted behavior. Wood and Gadow (2010) proposed that heightened anxiety triggers maladaptive coping responses (e.g., externalizing) as well as avoidance of social and adaptive tasks (e.g., social gathering, schoolwork). These responses relieve anxiety in the short-term, but increase the likelihood of greater avoidance and maladaptive behavior in the long-term (i.e., via negative reinforcement), escalating functional impairment. In keeping with these theories, several large studies have found linkages between clinical anxiety and increased severity of ASD symptoms, such as repetitive behaviors (Sukhodolsky et al. 2008), sensory symptoms (Mazurek et al. 2013), and total ASD symptoms (Kelly et al 2008), even when controlling for intellectual impairment, social difficulties, and level of speech impairment.

Despite the interwoven nature of these disorders, emerging research suggests that anxiety symptoms can be reliably differentiated and assessed in youth with ASD. Studies show convergent, concurrent, and discriminant validity for diagnostician-, child-, and parent-reports of anxiety symptoms that separate from autism symptoms (Kerns et al. 2014; Renno and Wood 2013; Storch et al. 2012a, b; Ung et al. 2014), though some studies also suggest variations in the construct and validity of anxiety in ASD depending assessment method (White et al. 2015; Kerns et al. 2015). Moreover, evidence suggests youth with ASD demonstrate similar biomarkers for anxiety, including similar physiological responses and genetic markers as those shown by typically developing (Gadow et al. 2009; 2010; Roohi et al. 2009). Cumulatively, these studies support the existence of anxiety in children with ASD that is separable from ASD symptom severity as well as significantly related to child functioning. Maladaptive and interfering anxiety is thus both an identifiable and potentially important treatment target for youth with ASD. Moreover, treatment of anxiety may positively impact not only anxiety symptoms, but also the severity of core ASD symptoms (Wood et al. 2009b).

Treatment of Anxiety in Youth with ASD

At present, no psychosocial or medication treatments for anxiety in school-aged children with ASD meets American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines for efficacy (Chambless and Hollon 1998). Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a psychosocial intervention that has produced improvements in anxiety for children without ASD with medium to large effect-sizes (Ollendick et al. 2006; Kendall et al. 2008; Walkup et al. 2008; Wood et al. 2006). CBT has been found to significantly improve anxiety symptoms in approximately 60% of treated youth, more than double the placebo response (Walkup et al. 2008), in addition to improving functional outcomes (Barrett et al. 2001; Wolk et al., 2015; Wood,2006). Yet, youth with ASD have traditionally been excluded from these efficacy trials.

Youth with ASD may have difficulty with standard practice CBT for various reasons, including their social and communication deficits, potentially interfering restricted and repetitive behaviors, lower insight and motivation to participate in treatment and distinct experience and/or expression of anxiety. Puleo and Kendall (2011) found that anxiety-disordered youth with moderate (compared to minimal) autism spectrum symptoms were more likely to respond to family versus individual CBT. These findings suggest that, with certain modifications, CBT may be accessible and beneficial to youth with ASD.

Several CBT protocols have been developed to reduce anxiety and OCD in youth with ASD (Chalfant et al. 2007; Reaven et al. 2012; Wood et al. 2009a; White et al. 2013; Sofronoff et al. 2005; Lehmkuhl et al. 2008). Modified protocols have included both group (White et al. 2013, Reaven et al. 2012; Chalfant et al. 2007) and individual formats (Wood et al. 2009a, b). Though efficient, the linear format of group therapy may limit matching intervention strategies to participant characteristics. Given the heterogeneity of phenotypes in ASD, individual interventions (e.g., modular treatments) tailored to a participant’s specific characteristics may be particularly advantageous (Mundy et al. 2007). Modular approaches may offer increased efficiency (reusability of modules, ease of tailoring, updating and reorganizing protocols) and effectiveness (e.g., more adaptable for applied contexts, diverse clinical presentations, comorbidity) relative to fixed protocols (Chorpita et al. 2005). Particularly, modular treatment may allow the flexibility necessary to address the often interwoven nature of anxiety and ASD symptoms, and promote improvement in overall functioning as well as core ASD and anxiety symptoms.

The Behavioral Interventions for Anxiety in Children with Autism (BIACA) program is an individual, modular CBT program for children with ASD. In an exploratory trial (Wood et al. 2009a) in children (ages 7–11 years) with ASD and comorbid anxiety (N=40), Wood et al. (2009a, b) found that BIACA was superior to a waiting list in anxiety response rate (76.5 vs. 8.7%); remission rate (52.9 vs. 8.7%); and overall clinical severity (d=2.5). Primary outcomes were comparable to those of CBT for typically developing children with anxiety disorders (Walkup et al. 2008; Wood et al., 2006). In a randomized controlled trial conducted by Storch et al. (2013a) (N=45), BIACA was associated with a significantly greater response rate (75%) than treatment-as-usual (TAU; 14%), with large between group effect size reductions in the anxiety symptoms of children with ASD (d=1.42). Further, in an exploratory trial of adolescents (ages 11–15 years) with ASD and comorbid anxiety BIACA (79%) was again superior to a waitlist (19%) in anxiety response rates (Wood et al. 2015). These findings were replicated in Storch et al. (2015). BIACA has also been associated with significant between group improvements in overall adaptive impairment (d=.58) and ASD symptom severity (d=.77) in children with ASD and comorbid anxiety (Drahota et al. 2011; Storch et al. 2015; Wood et al. 2009a, 2015).

Innovations of the TAASD Trial

The TAASD study stands apart from these studies due to its comparison of two CBT treatments, stringency of anxiety measurement, and power to examine potential moderators and mediators of treatment response.

Assessing the Relative Benefit of Care

TAASD will compare the Coping Cat program (Kendall et al. 1997), the BIACA program, and TAU. By so doing, the results will provide data regarding the efficacy of two versions of CBT for anxiety in ASD youth (comparisons of treatments to TAU), as well as comparisons of two programs with different emphases; Coping Cat addresses anxiety with a flexible manual-based approach; BIACA addresses anxiety with a manual-based approach that uses modules that can be selected to address ASD-related issues (e.g., social skill deficits, preoccupying interests, difficulties with generalization). Whereas the Coping Cat program has the potential advantage of a direct focus on anxiety and individualizes treatment within that focus, BIACA has the potential advantage of added modules to address ASD related issues as well as coordinated family involvement.

Differential Predictors of Treatment Response

The TAASD study will explore the question “What treatment works best for which participant” (Kiesler 1966)? Several potential moderators have been identified in multimodal trials comparing active treatments of child mental health disorders, including comorbidity, parent factors, and child insight (Compton et al. 2014; Garcia et al. 2010). Puleo and Kendall (2011) found that moderate autism symptoms in typically developing children with an anxiety disorder moderated treatment response for standard CBT versus family-based CBT. That is, youth with moderate ASD presentations were found to have benefited more from family CBT than from individual CBT. In addition, consistent with Mikami et al. (2010), Lerner et al. (2012) found that youth with ASD who rated their social abilities much higher than did their parents experienced significantly greater reductions in social anxiety following a social skills intervention. Given these findings, the role of ASD severity in differential CBT outcomes will be explored in the TAASD trial. For example, greater ASD symptom severity may hinder responsiveness to standard CBT, but not to a program designed to anticipate and address ASD-related challenges. Or, potentially, addressing anxiety and ASD issues may thin the focus on anxiety and result in non-differential outcomes. The TAASD trial will also explore whether treatment-related reductions in anxiety mediate improved autism symptoms or vice versa.

Enhancing Methodological Rigor and Outcome Measurement

Extant studies have been informative and have helped shape current practice. Nevertheless, studies with small samples or waitlist control conditions are less rigorous. By evaluating two versions of CBT as well as a TAU control condition (i.e., participants may participate in psychotherapy or psychotropic medication treatments in the community with monitoring by the research staff), TAASD results will add valuable practical and scientific information. Moreover, whereas the measures used in past studies have been more limited in focus (focused on anxiety but not ASD symptoms) and rigor (limited reliability/validity data for youth with ASD), TAASD employs a multi-method approach that includes diverse measures of anxiety with known psychometric properties in ASD samples as well as multiple measures of ASD symptomology.

Specific Aims and Hypotheses

To address the issues in the field and to conduct the “next needed” study, the research team opted for a full RCT with two active treatments and a TAU control condition, Independent Evaluators (IEs) blind to treatment condition, and the inclusion of measures with known psychometric properties among youth with ASD and anxiety. The following specific aims and hypotheses will be tested with this design:

Aim 1 Evaluate differential change over time in anxiety symptoms and response rates for the treatment conditions (Coping Cat, BIACA) compared to each other and relative to a TAU. Hypothesis: Independent evaluator ratings of anxiety severity will be significantly lower for participants receiving either of the CBT treatments relative to TAU at post-treatment and significantly lower for participants receiving (BIACA) relative to standard CBT at post-treatment.

Aim 2 Examine the durability of treatment gains for youth who are deemed treatment responders. Hypothesis: Week 16 treatment responders will remain significantly improved relative to baseline at the 6-month follow-up assessment.

Aim 3 Identify participant factors that are linked with differential treatment response (e.g., an interaction between treatment condition and ASD severity). Hypothesis: Autism symptom severity will moderate anxiety outcomes, with BIACA yielding greater reductions in anxiety for participants with more severe ASD.

Aim 4 Explore whether treatment reductions in anxiety mediate improved autism symptoms and whether treatment related reductions in autism symptoms mediate improved anxiety. Hypothesis: Reductions in anxiety due to treatment (either condition) will mediate improved autism symptoms. Also, reductions in autism symptoms due to treatment will be associated with improved anxiety.

Procedures and Management

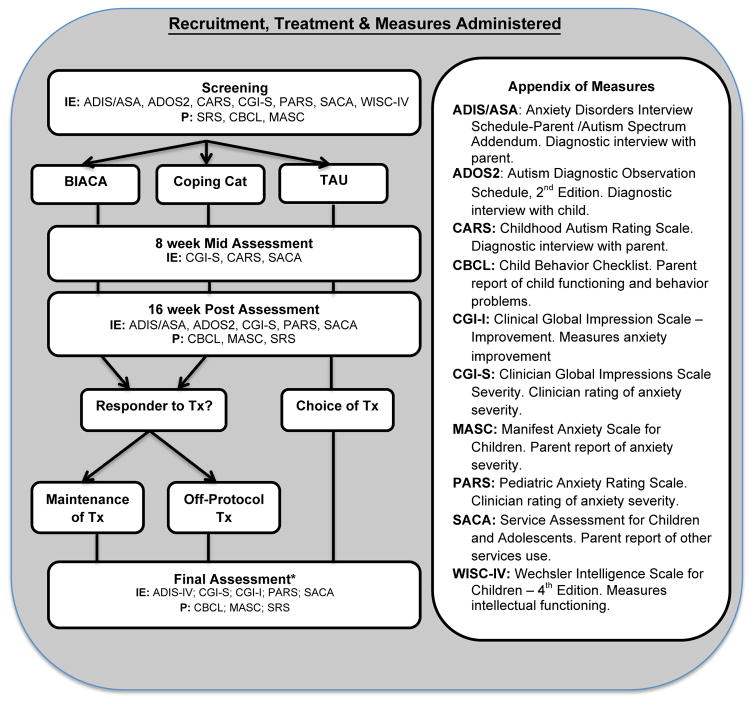

With federal funding, a 3-site study was approved in the spring of 2014 to recruit approximately 180 (60 per site) participants (aged 7–13 years) who meet criteria for ASD and anxiety over 3 years. At the time of this manuscript, 2 of the 3 years of the study had been completed. Study protocol is as follows. Assessments occur at screening, mid-treatment, post-treatment and 6-month follow-up. Participants meeting initial phone screen requirements attend a screening visit that includes informed consent (parent), assent (child) and comprehensive assessment of inclusion/exclusion criteria. Participants determined to be eligible during screening are randomly assigned using a computer-generated schedule to 16-weeks of BIACA (45% of sample), Coping Cat (45% of sample) or treatment as usual (TAU) in the community (10% of sample). Participants complete mid-treatment assessments after session 8 (week 8 for TAU) and post-treatment assessments within a week of their final treatment session (week 16 for TAU). Youth randomized to active treatment conditions may complete monthly booster sessions for 6-months after Post-treatment and a 6-month Follow-up Assessment. Youth in TAU are offered their choice of interventions (BIACA, Coping Cat) following the 16-week TAU period and complete a 2nd post-assessment after a subsequent 16 weeks of their elected treatment. Treatment responders are asked to delay any new services or medication changes until after the 6-month follow-up period; however, non-responders at post-treatment are allowed to pursue alternate treatment. Families complete 6-month follow-up assessments whether or not they pursue additional community-based treatment during the follow-up period (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Recruitment, treatment, and measures administered

The three sites are University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), University of South Florida (USF), and Temple University (TU). The A.J. Drexel Autism Institute, as a consultant to the study, collaborates with TU to oversee independent evaluations training and adherence for all sites. Data management and integrity are managed by USF, and therapy adherence is managed by UCLA and TU. A Steering Committee, comprised of the principal investigators, senior personnel and study coordinators, has weekly conference calls to review recruitment, protocol implementation, reporting and discussion of adverse events. In addition, weekly within- and between-site supervision meetings/phone conferences for therapists (separate calls for BIACA and Coping Cat cases) and independent evaluations ensure consistency in assessment and treatment implementation across sites and study years.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria along with the rationale for these criteria are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Outpatient youth ages 7 – 13 inclusive | Developmentally appropriate level for treatment |

| Meet criteria for ASD | Group of interest |

| Minimum score of 14 on PARS Severity items | Defines interfering level of anxiety |

| Minimum anxiety severity score of 3 on the CGI-S | Defines interfering level of anxiety |

| Verbal Comprehension IQ>70 | Verbal comprehension likely needed to profit from CBT |

| Anxiety symptoms are considered the primary mental health problem | Condition being treated |

| Stable on all psychiatric medications | Unstable medication may confound treatment |

|

| |

| Exclusion criteria | Rationale |

|

| |

| Receiving concurrent therapy targeting anxiety, social skills training or behavioral interventions | May confound treatment |

| Current clinically significant suicidality or individuals who have engaged in suicidal behaviors within 6 months | Require a higher level of care than provided |

| Been nonresponsive to an adequate trials of CBT for anxiety within the previous 2 years | Not likely to respond to study treatment |

| Lifetime bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | Require a higher level of care than provided |

| Initiation of a new psychiatric medication or a dose change on an established psychiatric medication | Medication effects can confound treatment |

Participants are required to meet criteria for ASD per the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule – Second Edition (ADOS-2; Lord et al. 2012), Child Autism Rating Scale-Second Edition (CARS-2HF; Schopler et al. 1980), and expert clinical judgment. In addition they are required to demonstrate interfering (i.e., clinically significant) anxiety (severity score ≥ 14 on the parent-reported PARS total, which excludes the symotom count item; Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study 2002). Interfering anxiety, rather than a specific anxiety disorder or disorders, determines eligibility because (a) CBT treatment is suitable for a range of anxiety symptoms; (b) clinically significant anxiety may arise in ASD that has a distinct presentation; and (c) treatment approaches that have applicability across multiple problem domains have more translational value than disorder-specific interventions. Youth are also required to score ≥ 70 on selected subscales (Vocabulary, Matrix Reasoning) of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV (WISC-IV). This cut-off, which has been used in prior trials (see White et al. 2013; Reaven et al. 2012; Wood et al. 2009a) was chosen to include a broader range of youth with ASD, but also select a group amenable to the cognitive and verbal demands of CBT.

Participants with comorbid depression, tic disorder or disruptive behavior disorders are enrolled as long as anxiety symptoms are principal (i.e., most impairing/distressing as determined by semi-structured diagnostic interview) after ASD. Participants taking psychotropic medications are allowed if the dose is stable and the family and prescriber affirm no plans to alter the dose or change medications in the foreseeable future. If a psychotropic medication is recently initiated or a dose changed, families have an allotted time to wait for stabilization. With regard to exclusionary criteria, only intervention services that require an extensive time commitment such as behavioral interventions (e.g., applied behavior analysis) or that target similar constructs as the study therapy (e.g., other anxiety therapy) restrict study participation. Other adjunctive services are allowable, and families can choose to discontinue ongoing behavioral or anxiety services to participate in the trial. These entry criteria are reflective of individuals with ASD, who tend to have multiple comorbidities, to be prescribed psychotropic medication and to be enrolled in a variety of adjunctive services (Mandell et al. 2008; Storch et al. 2013a; Wood et al. 2009a). The inclusion and exclusion criteria represent an effort to balance the internal and external validity of the study.

Sample Size/Power Estimates

With the proposed sample and using general linear mixed models (GLMM), there will be at least 80% power to detect a two-group (BIACA treatment vs Coping Cat treatment) difference of d=.47 averaged over the two post-screening treatment time points (Mid- and Post-treatment). There will also be at least 80% power to detect the Condition X Time interaction represented by a change from no difference at screening to a difference of d=.33 at posttreatment. Further, our power will be sufficient to detect group differences at any one time point, with group differences in the order of d=.44 during the acute treatment period and d=.53 at the 6 month follow-up resulting in 80% power at α=.05.

Independent Evaluator (IE) Blindness and Training

Qualified IEs blind to treatment condition conduct all assessments of target symptoms. IEs provide ratings and were trained at the study startup meeting using didactic presentation, discussion, and video exemplars. IEs are considered reliable when they score within 15% of the gold standard rating (PI’s mean rating) on the PARS and when they are within 1 point of the gold standard rating on the CGI-I and ADIS-IV-P severity ratings. All IEs achieve this standard of reliability, participate in weekly case conceptualization cross-site calls, and receive real-time supervision at each site. All ADOS-2 assessors are research-certified.

Although blindness may not be essential for obtaining reliable ratings of improvement (Compton et al. 2014), emphasis was placed on precautions needed to maintain IE blindness to treatment condition. Children and their families are provided with both written and verbal reminders prior to each assessment that emphasize the importance of not disclosing any treatment-identifying information to the evaluator. IEs do not attend clinical supervision meetings, have a work space separate from the treatment area, and are trained to avoid any discussion of treatment programs with families. Further, because there are two different treatment conditions, seeing the child in clinic would likely not unblind the IE to the specific treatment program.

Measures

During the study planning phase, measures were chosen based on their acceptable psychometric properties and their coverage of a range of anxiety and related behaviors in youth with ASD. Additional assessments included demographic variables, comorbid psychopathology, cognitive, and psychosocial functioning as well as treatment adherence, alliance, expectancy and satisfaction. The assessment protocol is as follows.

ASD Assessment

Autism symptom severity is assessed using measures that examine both (a) IE and (b) parent-report of symptoms. The measures provide both a categorical view of autism severity (i.e., inclusion diagnoses) as well as a continuous view for examining symptom severity throughout treatment.

Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2)

The ADOS-2 (Lord et al. 2012) is a semi-structured observational assessment administered directly to the participant to elicit social interaction, use of language, and observe potential restricted or repetitive behaviors. The ADOS-2, Module 3 is the primary tool for the assessing the presence of ASD at screening. The ADOS-2, Module 3 has appropriate sensitivity (.91) and specificity (.84; Gotham et al., 2007).

The Childhood Autism Rating Scale- Second Edition (CARS-2)

The CARS-2 (Perry et al. 2005; Schopler et al. 1980) is a 15-item clinician administered evaluation and direct observation measure of autism severity. The CARS-2 is completed at the screening assessment using information obtained from a parent interview, observations made during the ADOS, and the results of intelligence testing. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale to index its deviation from normative behavior, taking into account frequency, intensity, peculiarity, and duration. The CARS-2 was chosen due to its relative brevity and utility with higher functioning individuals. Psychometrics from the developer’s sample indicate that it has demonstrated internal consistency (.94), inter-rater reliability (.80), and retest stability (.88; Perry et al., 2005).

Social Responsiveness Scale: Parent Version – Second Edition (SRS)

The SRS (Constantino et al. 2004; Frazier et al. 2014) assesses the level of ASD symptomatology at screening, post-treatment, and at six-month follow-up. The SRS measures social deficits that are characteristic of ASD. Parents rate their child on a 4-point scale, focusing on observed aspects of routine reciprocal social behavior and preoccupations. The SRS allows for a continuous measure of ASD symptoms, including normal functioning, from the perspective of the parent in ways that are not directly tapped by the diagnostic interviews. It has demonstrated sound psychometric properties, including internal (.72–.93), inter-rater (.8), and retest reliability (.83; Constantino et al. 2003; Frazier et al. 2014) as well as demonstrated convergent validity (.7) with the ASD Diagnostic Interview-Revised. Further, recent research suggests that the SRS measures a construct that is distinct from anxiety (Constantino et al. 2003; Kerns et al. 2014; Renno and Wood 2013).

Anxiety Assessment

Anxiety is assessed using multiple measures, including continuous measures and diagnostic instruments. These instruments are designed to capture the wide range of interfering anxiety found in youth with ASD as well as systematically differentiate ASD and anxiety symptoms.

Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS)

The PARS (Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study, 2002) is a clinician-rated interview that assesses anxiety symptoms over the past week, as well as associated severity and impairment. PARS scores range from 0 to 25: children with a minimum score of 14 meeting criteria for anxiety. The PARS has been found to be sensitive to both CBT in anxious children with and without ASD (Walkup et al. 2008; Wood et al. 2009a), and has demonstrated good inter-rater reliability (.86), high test-retest reliability (.83), and convergent validity in anxious youth with ASD (Storch et al. 2012b).

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule: Parent Version and Autism Spectrum Addendum

The ADIS-P ( Silverman and Albano 1996) is a semi-structured interview for diagnosing anxiety disorders in youth ages 7 – 17 years. The ADIS-P has demonstrated inter-rater reliability (.91) and convergent validity (.51) in youth with ASD (Ung et al. 2014). In the present study, the ADIS-P includes an Autism Spectrum Addendum (ADIS/A; Kerns et al. 2014), a set of additional questions designed to systematically guide differential diagnosis of ASD and anxiety symptoms and capture impairing anxiety symptoms that arise in ASD, but do not fit traditional diagnostic categories (e.g., GAD, Social Phobia). Such symptoms include social fear without awareness of social ridicule; fears about novelty, change, or uncertainty; excessive worry about access to a circumscribed interest, and other unusual fears (e.g., men with beards). With the ADIS/A, anxiety symptoms are systematically differentiated from sensory aversions, perseverative behaviors and social deficits characteristic of ASD via specific probes that gather information on each child’s social awareness, social motivation, history of bullying and peer rejection, sensitivity to various sensations, perseverative interests and general cognitive rigidity. For example, unusual phobias as differentiated from sensory aversions by requiring that the child not only display a negative reaction to the stimuli (e.g., covering ears in response to a specific sound), but also anticipatory fear and avoidance of the stimuli as well as associated cues and contexts (e.g., avoidance of all department stores due to fear of loud speaker announcements). As another example, Social Anxiety Disorder is not diagnosed unless the child displays sufficient social motivation and awareness of negative evaluation to suggest that their social avoidance, distress and isolation are attributable, in part, to anxiety as opposed to ASD alone. Similarly, the child’s social worries are considered in light of their particular history of social rejection and bullying to determine if these concerns are excessive or realistic. Initial research with the ADIS-P/ASA supports its inter-rater reliability (.89–.99), 2-week retest reliability (.88–1.00) and convergent and divergent validity (Kerns et al. 2014).

Primary Outcome Measures

Response to modular versus standard CBT in reducing anxiety and ASD symptom severity is tested using the PARS (Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study, 2002), a categorical measure of treatment response, the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Scale (Guy 1976), and a continuous measure of autism severity, the SRS.

Clinical Global Impression Scales

The Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement Scale (CGI-I; Guy 1976) is a 7-point scale rating of treatment response anchored by 1 (“very much improved”) and 7 (“very much worse”). Responder status is defined as a CGI-rating of 1 or 2 (much/very improved) improved. The CGI-Severity (CGI-S) is a 7-point rating of severity anchored by 1 (“not at all ill”) and 7 (“extremely ill”). The CGI has demonstrated appropriate psychometric properties, with ratings associated with clinician-rated and self-report measures of anxiety symptom severity and impairment (Zaider et al. 2003). The CGI has been used in previous trials of CBT in anxious youth with and without ASD as an indicator of treatment response with medium to large effect-sizes (Storch et al., 2013a; Walkup et al. 2008).

Potential Moderators and Mediators

Moderation of ASD symptom severity will be examined through multi-method continuous measures, including an independent evaluator-rated measure (ADOS-2) and a parent-report questionnaire (SRS). In particular, we will examine whether children with greater ASD severity respond differentially when compared to TAU and when the two treatments are compared. Given the overlap of anxiety and autism symptoms, we will investigate the degree to which reductions in anxiety symptom severity (as measured by the PARS) mediate the effects of treatment on autism symptom severity (SRS), particularly the symptoms in the social domain. We will also examine the reverse mediation, or the degree to which autism symptoms mediate anxiety symptom severity following intervention.

Treatments

Many features of the treatment are similar: both are manual-based yet implemented flexibly, both target anxiety, and both follow principles and strategies associated with CBT. Although Coping Cat and BIACA both have 16 sessions, Coping Cat has weekly hour-long meetings whereas BAICA has weekly 90-min meetings. Rather than force a matched duration, the decision was made to implement the two treatments “as they have been implemented and evaluated in prior studies.” We will not control for differences in treatment duration because duration and treatment condition are the same (including treatment duration would be redundant). Rather, variability in weekly sessions length (60 v. 90 min) by treatment condition will be considered in the interpretation of findings. Specifically, we will consider the relative effort and resource use of each intervention given its relative efficacy.

BIACA

BIACA therapists work with families for 16 weekly sessions, each lasting approximately 90 min (45 min with the child and 45 min with the family/parents), implementing the BIACA manual (Wood et al. 2009a, b). BIACA elements include (1) teaching children to identify and label different emotional states in themselves and others, (2) providing families with psychoeducation about ASD and anxiety, (3) identifying core anxious cognitions as well as creating specific competing coping cognitions, (4) creating a structured rewards system and using the child’s areas of special interest to increase engagement and use of coping skills, (5) teaching the concept of gradual exposure (“baby steps”) and persistence (“keep practicing”) to habituate children to various anxiety-provoking triggers, and (6) providing supplementary social skills needed to successfully complete various exposure tasks and overcome realistic sources of anxiety (e.g., peer rejection, social isolation).

The manual includes four anxiety coping skills training modules (e.g., affect recognition and cognitive restructuring), which are integrated into an acronym (the “KICK” plan) to help children remember the skills. In addition, child daily living skills are addressed with the family in order to increase the child’s self-efficacy and confidence. Early in treatment, a hierarchy is developed identifying all target behaviors, including anxious and avoidant behaviors, social skill deficits, restricted and repetitive behaviors, and behavioral problems. Ultimate goals are set forth as measureable outcomes (e.g., “engage in appropriate peer play 100% of the time during recess”), which permits the delineation of specific proximal goals that gradually increase in difficulty. Anxiety and all other target behaviors are addressed using in vivo exposure therapy techniques during sessions and in the community, with children gradually introduced to greater anxiety-provoking situations over time. Therapeutic concepts are taught using multimodal stimuli (e.g., discussion scaffolded by drawing, writing, photographs and cartoons, and acting) and guided Socratic questioning, relying upon children’s special interests as metaphors to maintain enthusiasm and motivation. Children and parents are taught friendship skills (e.g., play-date hosting; joining peers at play) in several social modules. Parents (in weekly sessions) are taught to support children in entering and maintaining conversations or play. These skills are practiced at school, in the community, and on play-dates. To address unwanted and/or problematic repetitive behaviors, habit reversal procedures are implemented using incompatible replacement behaviors. All target behaviors are reinforced with a reward system for completion of at-home tasks. Points for various rewards and privileges are earned by completing these at-home tasks that are extensions of exposures completed and skills learned during treatment sessions. The modular format is guided by an algorithm designed to address each child’s clinical needs within the 16-session format (Sze and Wood 2008).

A typical progression through treatment is as follows. All families are first given an introduction and some psychoeducation regarding the nature of ASD and anxiety as well as how each can increase difficulties within the child. If the child presents any adaptive functioning deficits, a self-help skills and autonomy-granting module is used with the family. Coping skills training commences, with social intervention and friendship skills modules presented if the child has significant social skills deficits. An anxiety hierarchy and reward system specifically tailored to produce maximum motivation is then created for each child. In-vivo and corresponding home-based exposures are then repeated continuously until symptom remission. If the child has obsessions or compulsions, then an exposure/response prevention module is used. If a child has special interests or preoccupations that interfere with their social engagement, a special interest suppression module is used.

Coping Cat

Participants randomized to Coping Cat program receive 16 weekly 60-min sessions that represent the standard of practice for individual child-focused CBT for anxiety found to be effective in multiple trials (Kendall et al. 2008; Walkup et al. 2008). The first eight sessions focus on teaching skills to the child, whereas the second eight sessions provide the child the opportunity to practice newly learned skills (through exposure tasks) both within and between sessions (homework). The goal is to teach youth to recognize the signs of unwanted anxious arousal and to let these signs serve as cues for the use of anxiety management strategies.

The main features are: (1) recognizing anxious feelings and somatic reactions to anxiety, (2) identifying cognition in anxiety-provoking situations (i.e., unrealistic or negative expectations), (3) developing a plan to cope with the situation (i.e., modifying anxious self-talk into coping self-talk as well as identifying coping actions that might be effective), (4) behavioral exposure tasks, and (5) evaluating performance and self-reinforcement for effort. The treatment uses behavioral training strategies such as affect labeling in self and others, modeling, imaginal and in vivo exposure tasks, role-play, and contingent reinforcement. To help reinforce and generalize the skills, specific homework tasks are assigned and monitored within the child Coping Cat workbook (Kendall and Hedtke 2006). Points (to be used for various rewards and privileges) are earned by completing in-session and at-home tasks that are extensions of exposures completed and skills learned during treatment. Parent involvement in the child’s treatment occurs (weekly update, scheduling, etc.) and parents may be included in exposure tasks. Parents consult in the child’s treatment, and are given a model for assisting with the treatment in the role of the child’s “cognitive behavioral coach.” In addition to a regular 15-min check-in at the start of each session, parents are scheduled for meetings with the therapist after the 3rd and 8th sessions, and prior to the end of treatment. Parents are also given a copy of the Parent Companion (Kendall et al. 2010), a pamphlet that describes their child’s treatment and their potential contributions as parents to beneficial outcomes.

TAU

Participants randomized to the TAU condition receive care but wait for a period of 16 weeks before receiving treatment in the context of the study. During this time, youth may receive psychotherapy and/or initiate or change current psychiatric medication (if applicable). Eight weeks into the TAU period, youth participate in a mid-point assessment. This assessment in conjunction with bi-weekly check-in calls will allow the research staff to monitor the participant during the TAU period. If a participant’s anxiety worsens during this phase, PIs determine if the TAU period should be cut short. After completion of the post TAU assessment, TAU youth and their families are offered treatment (BIACA or Coping Cat). The TAU condition allows for the examination of potential differences in response relative to care available in the community, an important comparison if both CBT conditions demonstrate positive yet similar response rates. The TAU condition also provides data regarding the feasibility of CBT in treating youth with ASD and comorbid anxiety as well as estimates for tests of differential outcome. Although CBT is the gold standard for typically developing youth, this has not been established in youth with ASD and anxiety.

Participant Safety, Adjunctive Services and Attrition Prevention

Procedures for Monitoring Participant Safety

Participant safety is a foremost consideration in the TAASD study. Effective screening and mental health evaluations help to determine the appropriateness of participation. If at any point, symptoms become distressing or dangerous, participants are withdrawn from the study and, as needed, alternative treatments are instituted.

Adverse events (AEs) are monitored. The project coordinator conducts weekly inquiries regarding any health complaints, recent illness or injury, and need for medical consultation. This allows detection and appropriate response to any adverse event experienced by the child while maintaining the blindness of the independent evaluator. All AE complaints are relayed to the site PI and treating clinician who take immediate action, which may include monitoring, adjunctive intervention within study protocol, or removal from the study and provision of off-protocol intervention. We also administer a standard form at every treatment session and assessment to ascertain the presence of any thoughts, wishes, or behaviors related to self-harm or harm to others since the last study contact. This was included given recent FDA concerns regarding suicidality and antidepressant medication, which participants in this study may be taking.

Adjunctive Services and Attrition Prevention (ASAP)

It is not possible to define a priori all possible situations that may require adjunctive services during the course of a long and complex trial. The potential for suicidality and self-injurious behaviors in participants was particularly considered in this trial. ASD is associated with many risk factors for suicidality such as social isolation, bullying, and elevated internalized symptoms (Cappadocia et al. 2012; van Steensel et al. 2011). Storch and colleagues (Storch et al. 2013b) found that approximately 11% of treatment seeking youth with autism spectrum disorder and co-occurring anxiety had suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Additionally, there is the potential for self-injurious behavior associated with anxiety in youth with ASD (Kerns et al. 2015).

Prior to study launch, a plan for potential risks associated with having ASD was developed based on strategies implemented in other large federally funded multisite RCTs (March et al. 2006; Walkup et al. 2008). To address participant crises or unusual needs/circumstances that arise, additional treatment sessions (i.e., ASAP sessions, as in Child/Adolescents Anxiety Multimodal Study; Walkup et al. 2008) are provided to address these needs and facilitate participant retention. A maximum number of sessions are allowed for each phase of the study (Screening: 1; Acute Treatment: 2; Follow-up: 2). Participants who require more than this limited intervention are prematurely terminated as defined below.

At any time, participants may have deteriorated or developed crises that led the site team to recommend additional off protocol treatments above and beyond that provide by ASAP described above. Such “prematurely terminated” participants may continue to be treated within their assigned treatment arm, and we continue to collect assessments. Participants who are “prematurely terminated” will be distinguished from “drop outs”—defined as participants who refused to furnish further data or who refused study treatment or both. Stated differently, dropouts are defined as those participants who withdraw consent to participate whereas premature terminators are defined as participants for whom study treatments require supplementation and are therefore withdrawn by the study team. Study drop outs are encouraged to return for a last assessment, which is then followed by end-of-treatment recommendations.

All participants who have an insufficient response at posttreatment (or anytime during the follow-up period) are offered appropriate referrals in the community for continued support. During the follow-up period, participants are seen for booster sessions in their respective treatment arm every 4 weeks for the 6-month duration, which is similar to the protocol in other trials (March et al. 2006; Walkup et al. 2008). Strict rescue criteria are used if a child’s symptoms worsen meaningfully, the child requires a higher standard of care (i.e., inpatient), and/or the child experiences suicidality or meaningful side effects.

Quality Assurance and Data Management

Multisite studies benefit from a distribution of tasks. Throughout TAASD, both assessments and therapy are checked for quality assurance. TU serves as the quality assurance site for IE measures and will review 20% of assessments to assess inter-rater reliability by study completion. The UCLA site assesses therapy quality assurance by having experienced raters rate two randomly selected tapes per child: one tape from the early phase of therapy (sessions 1–6) and one from the late phase (sessions 7–16). TU also rates treatment integrity for the Coping Cat cases. By study completion, 15% percent of these rated tapes will be rated for internal reliability by a secondary person. USF manages data analysis and security. A secure online data collection software collects participant data across sites. Specific identifiers and codes restrict access to authorized personal. Routine monitoring is performed by the study PI’s and throughout the study an independent Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) will oversee data collection.

Design Challenges and Paths not Taken

Why Not Compare CBT to Pharmacotherapy or Combined Treatment?

Based on an evaluation of the literature, and with expert consultant input, it was decided that the use of a medication comparison was not justified given the limited supporting efficacy data for youth with ASD. There have been no controlled, well-powered studies of (SSRIs) for anxiety in ASD. Recently, the NIH STAART Autism Network supported a multi-site trial testing the efficacy of citalopram versus placebo for high levels of repetitive behavior in 149 youth with ASD (King et al. 2009). No benefit of citalopram was observed on the primary treatment target, repetitive behaviors (Mdosage=16.5mg/day). Most studies of SSRIs in ASD involve small, mixed samples (McDougle et al. 2003), usually in open trial formats (Steingard et al. 1997), with varying efficacy endpoints and target symptoms. Therefore, non-pharmacological interventions for anxiety in ASD have significant public health implications.

Based on the participant characteristics of similar samples in prior studies (Wood et al. 2009a, 2015), it is expected that some participants will be taking psychoactive medication. Medication dosage is monitored throughout treatment to ensure there are no changes in dose or medication that could influence the results. Maintaining a stable dose helps address the concern that changes in anxiety might be linked to psychoactive medication use. Medication use will also be considered in the data analyses.

Why Compare Two Active CBT Treatments?

Using TAU, along with two versions of CBT allows a test of efficacy of CBT for anxiety in ASD. Moreover, it permits a test of the relative strengths of a modular CBT that addresses potentially relevant ASD features (e.g., social skills) and a CBT that directly addresses anxiety. A non-specific or non-CBT comparison condition may not be acceptable to families, may be linked to high attrition, and is not likely to yield meaningful gains in youth with ASD.

Differentiation of Anxiety and ASD

Although some symptoms of anxiety and of ASD are similar (e.g., social avoidance, perseveration) and potentially related, the underlying pathology of these disorders likely differs (Kerns and Kendall 2012). The assessment instruments needed for proper study in an ASD-and-anxiety sample should be able to effectively differentiate anxiety from ASD symptoms and converge with other measures of anxiety (Storch et al. 2012a, b). The primary symptom outcome measure (PARS) is an IE-administered measure with evidence of convergent and discriminant validity within samples of youth with ASD that permits refined questioning about the nature of anxiety symptoms, an assessment approach that is likely to lead to increased precision. In addition, for research purposes, TAASD uses additional measures (e.g., the ADIS/A) created to aide in distinguishing anxiety symptoms and ASD symptoms and to capture symptoms of anxiety that may have a differential treatment response.

Why Not Conduct a Single Site Trial?

Although cost and project complexity are greater with a multi- over a single-site study, the use of multiple sites allow for rapid participant recruitment and the dissemination of the findings. Moreover, each site offers its own area of expertise in the tested treatments and assessments. Multiple sites also allow for greater generalizability by providing greater heterogeneity in the ethnicity and socio-demographic characteristics of participants. Finally, a multi-site study provides data regarding treatment transportability.

Conclusion

There is a growing and pressing need to know the relative efficacy of treatments for anxiety in youth with ASD and anxiety. To date, no RCTs have evaluated the relative efficacy of standard CBT for anxiety in children with ASD, modular CBT for youth with ASD and anxiety, and TAU. Moreover, there are limited data on the potential moderators and/or mediators of how and when different versions of CBT are needed for children with ASD. Such data will be an instrumental stepping-stone to effective dissemination and implementation.

References

- Barrett PM, Duffy AL, Dadds MR, Rapee RM. Cognitive–behavioral treatment of anxiety disorders in children: Long-term (6-year) follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:135–141. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.69.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellini S. Social skill deficits and anxiety in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developental Disorders. 2004;19:78–86. doi: 10.1177/10883576040190020201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cappadocia MC, Weiss JA, Pepler D. Bullying experiences among children and youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42:266–277. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfant AM, Rapee R, Carroll L. Treating anxiety disorders in children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders: A controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37:1842–1857. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0318-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:7–18. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Weisz JR. Modularity in the design and application of therapeutic interventions. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 2005;11:141–156. doi: 10.1016/j.appsy.2005.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Compton SN, Peris TS, Almirall D, Birmaher B, Sherrill J, Kendall PC, Albano AM. Predictors and moderators of treatment response in childhood anxiety disorders: Results from the CAMS trial. Journal of Consulingt and Clinical Psychol. 2014;82:212–224. doi: 10.1037/a0035458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Davis SA, Todd RD, Schindler MK, Gross MM, Brophy SL, Reich W. Validation of a brief quantitative measure of autistic traits: Comparison of the social responsiveness scale with the autism diagnostic interview-revised. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2003;33:427–433. doi: 10.1023/A:1025014929212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Gruber CP, Davis S, Hayes S, Passanante N, Przybeck T. The factor structure of autistic traits. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:719–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drahota A, Wood JJ, Sze KM, Van Dyke M. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on daily living skills in children with high-functioning autism and concurrent anxiety disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2011;41:257–265. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1037-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier TW, Ratliff KR, Gruber C, Zhang Y, Law PA, Constantino JN. Confirmatory factor analytic structure and measurement invariance of quantitative autistic traits measured by the Social Responsiveness Scale-2. Autism: The InternationalJjournal of Research and Practice. 2014;18:31–44. doi: 10.1177/1362361313500382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Roohi J, DeVincent CJ, Kirsch S, Hatchwell E. Association of COMT (Val158Met) and BDNF (Val66Met) gene polymorphisms with anxiety, ADHD and tics in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:1542–1551. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0794-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Roohi J, DeVincent CJ, Kirsch S, Hatchwell E. Glutamate transporter gene (SLC1A1) single nucleotide polymorphism (rs301430) and repetitive behaviors and anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010;40:1139–1145. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-0961-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AM, Sapyta JJ, Moore PS, Freeman JB, Franklin ME, March JS, Foa EB. Predictors and moderators of treatment outcome in the Pediatric Obsessive Compulsive Treatment Study (POTS I) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:1024–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.06.013. quiz 1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham K, Risi S, Pickles A, Lord C. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule: Revised algorithms for improved diagnostic validity. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37:613–627. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0280-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: National Institute for Mental Health; 1976. Clinical Global Impressions; pp. 218–222. Vol. Revised DHEW Pub. (ADM) [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AB, Garnett MS, Attwood T, Peterson C. Autism spectrum symptomatology in children: The impact of family and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:1069–1081. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Flannery-Schroeder E, Panichelli-Mindel SM, Southam-Gerow M, Henin A, Warman M. Therapy for youths with anxiety disorders: A second randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychol. 1997;65:366–380. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Hedtke K. Coping Cat Workbook. 2. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Hudson JL, Gosch E, Flannery-Schroeder E, Suveg C. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: a randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:282–297. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Podell J, Gosch E. The Coping Cat: Parent Companion. Armore: Workbook Publishing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kerns CM, Kendall PC. The presentation and classification of anxiety in autism spectrum disorder. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2012;19:323–347. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns CM, Kendall PC, Berry L, Souders MC, Franklin ME, Schultz RT, … Herrington J. Traditional and atypical presentations of anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2014;44:2851–2861. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2141-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns CM, Kendall PC, Zickgraf H, Franklin ME, Miller J, Herrington J. Not to be overshadowed or overlooked: functional impairments associated with comorbid anxiety disorders in youth with ASD. Behavior therapy. 2015;46:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiesler DJ. Basic methodologic issues implicit in psychotherapy process research. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 1966;20:135–155. doi: 10.1037/h0022911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BH, Hollander E, Sikich L, McCracken JT, Scahill L, Bregman JD, Ritz L. Lack of efficacy of citalopram in children with autism spectrum disorders and high levels of repetitive behavior: citalopram ineffective in children with autism. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:583–590. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmkuhl HD, Storch EA, Bodfish JW, Geffken GR. Brief report: Exposure and response prevention for obsessive compulsive disorder in a 12-year-old with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38:977–981. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0457-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner MD, Calhoun CD, Mikami AY, De Los Reyes A. Understanding parent-child social informant discrepancy in youth with high functioning autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42:2680–2692. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1525-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S, Gotham K, Bishop SL. (ADOS-2) Manual (Part 1): Modules 1–4. 2. 2012. Autism diagnostic observation schedule. [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, Morales KH, Marcus SC, Stahmer AC, Doshi J, Polsky DE. Psychotropic medication use among Medicaid-enrolled children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e441–448. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March J, Silva S, Vitiello B, Team T. The treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS): Methods and message at 12 weeks. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:1393–1403. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000237709.35637.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes SD, Calhoun SL, Aggarwal R, Baker C, Mathapati S, Molitoris S, Mayes RD. Unusual fears in children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2013;7:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2012.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek MO, Vasa RA, Kalb LG, Kanne SM, Rosenberg D, Keefer A, et al. Anxiety, sensory over-responsivity, and gastrointestinal problems in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41:165–176. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9668-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougle CJ, Stigler KA, Posey DJ. Treatment of aggression in children and adolescents with autism and conduct disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2003;64(Suppl 4):16–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami AY, Calhoun CD, Abikoff HB. Positive illusory bias and response to behavioral treatment among children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:373–385. doi: 10.1080/15374411003691735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy PC, Henderson HA, Inge AP, Coman DC. The modifier model of autism and social development in higher functioning children. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 2007;32:124–139. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.32.2.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, King NJ, Chorpita BF. Empirically supported treatments for children and adolescents. In: Kendall PC, editor. Child and adolescents therapy: Cognitive-behavioral procedures. 3. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 492–520. [Google Scholar]

- Perry A, Condillac RA, Freeman NL, Dunn-Geier J, Belair J. Multi-site study of the childhood autism rating scale (CARS) in five clinical groups of young children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005;35:625–634. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puleo CM, Kendall PC. Anxiety disorders in typically developing youth: Autism spectrum symptoms as a predictor of cognitive-behavioral treatment. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2011;41:275–286. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaven J, Blakeley-Smith A, Culhane-Shelburne K, Hepburn S. Group cognitive behavior therapy for children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders and anxiety: A randomized trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53:410–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renno P, Wood JJ. Discriminant and convergent validity of the anxiety construct in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43:2135–2146. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1767-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study G. The pediatric anxiety rating scale (PARS): Development and psychometric properties. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:1061–1069. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roohi J, DeVincent CJ, Hatchwell E, Gadow KD. Association of a monoamine oxidase-a gene promoter polymorphism with ADHD and anxiety in boys with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:67–74. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0600-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopler E, Reichler RJ, DeVellis RF, Daly K. Toward objective classification of childhood autism: Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1980;10:91–103. doi: 10.1007/BF02408436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Albano AM. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV.: Parent interview schedule. Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T, Chandler S, Loucas T, Baird G. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:921–929. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofronoff CK, Attwood T, Hinton S. A randomised controlled trial of a CBT intervention for anxiety in children with Asperger syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:1152–1160. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steingard RJ, Zimnitzky B, DeMaso DR, Bauman ML, Bucci JP. Sertraline treatment of transition-associated anxiety and agitation in children with autistic disorder. Journal of Childand Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 1997;7:9–15. doi: 10.1089/cap.1997.7.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Arnold EB, Lewin A, Nadeau J, Jones AM, de Nadai AS, Murphy T. The effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus treatment as usual for anxiety in children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013a;52(2):132–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Ehrenreich May J, Wood JJ, Jones AM, De Nadai AS, Lewin AB, Murphy TK. Multiple informant agreement on the anxiety disorders interview schedule in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal Of Child And Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2012a;22:292–299. doi: 10.1089/cap.2011.0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Lewin AB, Collier AB, Arnold E, De Nadai AS, Dane BF, Murphy TK. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus treatment as usual for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and comorbid anxiety. Depression and Anxiety. 2015;32:174–181. doi: 10.1002/da.22332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Sulkowski ML, Nadeau J, Lewin AB, Arnold EB, Mutch PJ, Murphy TK. The phenomenology and clinical correlates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013b;43:2450–2459. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1795-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Wood JJ, Ehrenreich-May J, Jones AM, Park JM, Lewin AB, Murphy TK. Convergent and discriminant validity and reliability of the pediatric anxiety rating scale in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012b;42:2374–2382. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1489-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhodolsky DG, Scahill L, Gadow KD, Arnold LE, Aman MG, McDougle CJ, Vitiello B. Parent-rated anxiety symptoms in children with pervasive developmental disorders: Frequency and association with core autism symptoms and cognitive functioning. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:117–128. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze KM, Wood JJ. Enhancing CBT for the treatment of autism spectrum disorders and concurrent anxiety. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2008;36:403–409. doi: 10.1017/S1352465808004384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ung D, Arnold EB, De Nadai AS, Lewin AB, Phares V, Murphy TK, Storch EA. Inter-rater reliability of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV in high-functioning youth with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 2014;26:53–65. doi: 10.1007/s10882-013-9343-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of the autism spectrum disorders-autism and developmental disabiolties monitoring network, United States. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2009;58:SS-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Steensel FJA, Bögels SM, Perrin S. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child And Family Psychology Review. 2011;14:302–317. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0097-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmar FR, Klin A. Diagnostic issues in Asperger syndrome. In: Klin A, Volkmar FR, editors. Asperger Syndrome. Vol. 27. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. pp. 25–71. [Google Scholar]

- Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, Birmaher B, Compton SN, Sherrill JT, Kendall PC. Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359:2753–2766. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Lerner MD, McLeod BD, Wood JJ, Ginsburg GS, Kerns C, et al. Anxiety in youth with and without autism spectrum disorder: examination of factorial equivalence. Behavior Therapy. 2015;46:40–53. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Ollendick T, Albano AM, Oswald D, Johnson C, Southam-Gerow MA, … Scahill L. Randomized controlled trial: Multimodal anxiety and social skill intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43:382–394. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1577-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Oswald D, Ollendick T, Scahill L. Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:216–229. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk CB, Kendall PC, Beidas RS. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for child anxiety confers long-term protection from suicidality. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;54:175–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ. Effect of anxiety reduction on children’s school performance and social adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:345–349. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.345. 2006-03514-012 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Drahota A, Sze K, Har K, Chiu A, Langer DA. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009a;50:224–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01948.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Drahota A, Sze K, Van Dyke M, Decker K, Fujii C, Spiker M. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on parent-reported autism symptoms in school-age children with high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009b;39:1608–1612. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0791-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Ehrenreich-May J, Alessandri M, Fujii C, Renno P, Laugeson E, … Storch EA. Cognitive behavioral therapy for early adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and clinical anxiety: A randomized, controlled trial. Behavior Therapy. 2015;46:7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Gadow KD. Exploring the nature and function of anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2010;17:281–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01220.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Piacentini JC, Southam-Gerow M, Chu BC, Sigman M. Family cognitive behavioral therapy for child anxiety disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:314–321. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000196425.88341.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaider TI, Heimberg RG, Fresco DM, Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR. Evaluation of the clinical global impression scale among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:611–622. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]