Abstract

Objective

This study examines the potential effects of nativity and acculturation on active life expectancy (ALE) among Mexican-origin elders.

Method

We employ 17 years of data from the Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly to calculate ALE at age 65 with and without disabilities.

Results

Native-born males and foreign-born females spend a larger fraction of their elderly years with activities of daily living (ADL) disability. Conversely, both foreign-born males and females spend a larger fraction of their remaining years with instrumental activities of daily life (IADL) disability than the native-born. In descriptive analysis, women with low acculturation report higher ADL and IADL disability. Men manifest similar patterns for IADLs.

Discussion

Although foreign-born elders live slightly longer lives, they do so with more years spent in a disabled state. Given the rapid aging of the Mexican-origin population, the prevention and treatment of disabilities, particularly among the foreign born, should be a major public health priority.

Keywords: active life expectancy, disability, Hispanic health, Mexican elders, acculturation

Introduction

Americans are living longer than ever before. In 2013, life expectancy at birth in the United States was 78 years, and those who survived to age 65 could expect to live to 84 (Arias, 2012). Among those over 65, the proportion of the population 85 to 94 years old experienced the fastest growth between 2000 and 2010, increasing from 3.9 million to 5.1 million, a growth rate of 29.9% (Werner, 2011). All segments of the population have benefited from declining mortality; however, substantial gender and race/ethnic differentials in life expectancy remain, although they are not always what one might expect (Hayward, Warner, & Crimmins, 2007). The Black and Mexicanorigin populations share a similar disadvantaged socioeconomic profile, and on average, the Mexican-origin population has very low levels of education, a major morbidity and mortality risk factor (Crimmins, Hayward, & Seeman, 2004). Yet, while Blacks experience higher levels of morbidity and shorter life spans than non-Hispanic Whites, the Mexican-origin population enjoys average life expectancies at birth and at age 65 that are equal to if not longer than those of non-Hispanic Whites (Palloni & Arias, 2004). In 2008, Hispanic women who survived to age 65 could expect to live to 87, and Hispanic men who survived to age 65 could expect to live to 84. Non-Hispanic White women and men who survived to age 65 could expect to live to 85 and 82 respectively, and African-American women and men could expect to live to 83 and 80, respectively (Arias, 2010).

These statistics reveal a consistent female advantage in life expectancy. Yet even among women, other social factors, including nativity, affect life expectancy. Among Hispanic women, the foreign-born have the longest life expectancies at age 65 (Cantu, Hayward, Hummer, & Chiu, 2013; Palloni & Arias, 2004). The general female mortality advantage and their longer life spans raise questions concerning both the reasons for this female advantage and the cultural and socioeconomic factors that account for racial and ethnic group differences. It also raises questions related to the quality of life and level of functioning that characterizes the additional years that women live. Based on a study that estimated active life expectancy (ALE) using performance-oriented mobility assessments or POMAs among Mexican-origin individuals 65 or older, researchers found that foreign-born Mexican-origin women spend the greatest number of years, as well as the largest proportion of years after 65, with physical mobility limitations (R. J. Angel, Angel, & Hill, 2014). Foreign-born Mexican-origin women spend 64% of their remaining years with serious limitations in physical functioning based on the POMA, compared with 61% for native-born women, 52% for foreign-born men, and 53% for native-born men (Angel et al., 2014). Of course, because Mexicanorigin women in the United States live longer than men or native-born women, they have a greater opportunity to experience health problems (J. L. Angel, Torres-Gil, & Markides, 2012; Markides, Rudkin, Angel, & Espino, 1997).

In this article, we use a longitudinal sample of Mexican-origin individuals 65 and older to compare estimates of ALE based on two widely used measures of functional capacity, basic Activities of Daily Living (ADLs), and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs). Assessments of problems with the independent performance of ADLs and capacity to carry out IADLs are commonly used measures of disability and independence (Spector & Fleishman, 1998). Our objective is to explore the potential role of acculturation on estimates of ALE based on these two measures. These two measures of functional capacity differ in important respects that may affect the manner in which acculturation and gender affect each. ADLs refer to basic functional capacities, such as the ability to carry out self-care activities such as bathing, dressing, and toileting (Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson, & Jaffe, 1963). ADLs represent specific and concrete measures of disability and predict the risk of long-term care (Kane, Kane, & Ladd, 1998). IADLs, however, assess one’s ability to carry out more complex activities that require cognitive competence and some familiarity with the local cultural environment. Such tasks include driving, managing finances, and performing light housekeeping (Lawton & Brody, 1969). Given the more contextually dependent nature of IADLs, we hypothesize that acculturation will have a greater impact on estimates of ALE based on this scale. Our operationalization of acculturation consists of language proficiency which subsumes two highly related conceptual dimensions: culture and linguistic competency. This measure, therefore, does not tap other dimensions of acculturation, including belief systems and group-specific behaviors.

A Model of ALE: Issues of Culture and Gender

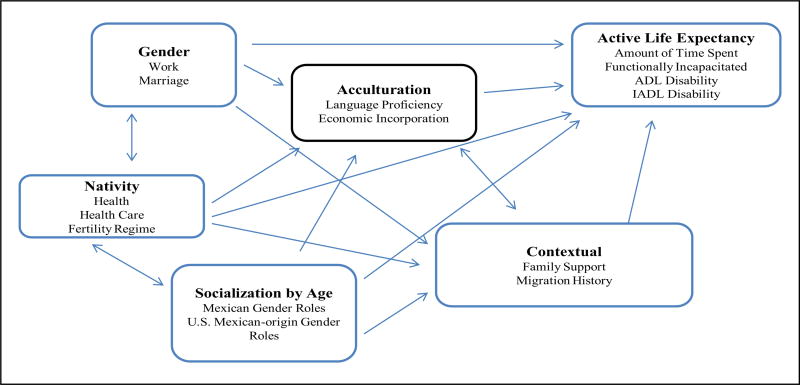

Figure 1 presents a conceptual model that includes factors that influence ALE, defined in terms of the number of years spent with either an ADL or IADL disability prior to death among older adults of Mexican-origin. Such estimates of the length of life spent in a disabled state are influenced by the respondent’s subjective understanding of the questions used to assess functional status and the ability to carry out more complex life-management tasks. Although such subjective measures clearly reflect actual functional capacity as they might be assessed by an independent observer, self-reports are complex cognitive and culturally influenced constructs that may reflect more than an objective state (Glass, 1998). Our conceptual model as depicted in Figure 1 is based on the assumption that lower levels of acculturation are associated with more traditional gender and family roles, which include less experience with activities such as driving and managing finances. Greater acculturation reflects more familiarity with American culture and less of a dependence on a spouse or other family members.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model of healthy aging for older Hispanics.

Note. ADL = Activities of Daily Living; IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living.

A number of scholars find evidence for a gender-based Mexican cultural orientation which places great value on the family and defines woman’s core roles as those of wife, nurturer, and caregiver (Baca Zinn & Pok, 2002). A husband’s core role is to serve as a provider and decision maker. Given such traditional gender and family role orientations, women may report greater competence in performing such tasks as shopping, cooking, and doing laundry than men (Lawton & Brody, 1969). Men, however, may be more likely to carry out such tasks as driving and handling money (Lawton & Brody, 1969). These distinctions in the cultural and gender-based content of the items making up the disability measures are important because they may be affected by acculturation, a concept defined in terms of the adoption of the social norms and traits of a host society (Abraido-Lanza, Armbrister, Florez, & Aguirre, 2006).

Acculturation, then, is a central focus of the analysis because it determines the extent to which one adopts traditional gender-based behaviors across different spheres of daily activity (Abraido-Lanza et al., 2006). Lower acculturation decreases the ability of Mexican-origin women’s ability to perform more complex tasks, such as managing finances and driving. The reason for this is that less-acculturated Mexican-origin women in the United States are a particularly disadvantaged population (Kim et al., 2011; Parrado & Flippen, 2005). They lack critical social and economic resources needed to age successfully (R. J. Angel & Angel, 2009). Moreover, Mexican immigrants have a higher fertility regime than U.S.-born Mexican-origin women in the United States (Martin et al., 2012). As a result, immigrant Mexican-origin women have fewer opportunities to work outside the home than the U.S.-born and thus be more inclined to report fewer difficulties with performing the tasks needed to maintain a household, such as cleaning, cooking, and housekeeping. Assimilation is important in the Mexican American population in terms of enhancing financial well-being (Borjas, 2005). Fewer years spent in the United States also increase the risk of poverty at age 65, wealth accumulation, and dependency on family and the government among Mexican-origin immigrant elders (R. J. Angel & Angel, 2009).

Although we do not have direct measures of gender or family roles, we use an acculturation scale, as well as other variables related to a traditional orientation, including education, and marriage to tap potential differences in gender and family roles. Our analysis is motivated by the wide use of self-reported ADLs and IADLs in the literature on functional capacity, and they are used widely in comparative research of group differences in functional decline and ALE (Chiu & Wray, 2011; Minicuci et al., 2004; Wiener, Hanley, Clark, & Nostrand, 1990). The possibility of cultural and gender influences on the measurement characteristics of these scales has important implications for population research and public policy (Lynch, Brown, & Harmsen, 2003). An understanding of cultural influences on disability also contributes to the literature on the nexus of gender and immigration as it relates to ALE.

Mindful of gender inequalities in work and family roles for the Mexicanorigin population in the United States, our major analytic task is to determine the extent to which traditional gender roles associated with nativity and acculturation influence the likelihood of disability-free life expectancy for Mexican elderly 65 and older. We should note that we are testing a portion of this model and are unable to pay close attention to certain components of the model, including psychological aspects of age-graded socialization. We expect that individuals with low acculturation to have higher levels of IADL than ADL net of nativity. High acculturation is associated with a lower need for IADL assistance due to reluctance to ask for help. Social context, however, is an important consideration. Individuals who have low education and physically demanding jobs are more likely to report a need for assistance with both ADL and IADL disability.

Data

We use data from the Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly (H-EPESE) to estimate the proportion of life spent in a disabled state prior to death for native-born and foreign-born Mexican-origin men and women. The H-EPESE is a longitudinal cohort study of community-dwelling Hispanic elderly, aged 65 years and older, residing in the five southwestern states of Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas (Markides et al., 1997). The H-EPESE has been used extensively to study the prevalence of disability among Mexican-origin adults in the United States (Peek, Ottenbacher, Markides, & Ostir, 2003; Peek, Patel, & Ottenbacher, 2005).

These data provide detailed information on risk factors for physical illness and mortality for a sample of 3,050 individuals of Mexican-origin who were first interviewed in 1993–1994. This panel was re-contacted in 1995–1996, 1998–1999, 2000–2001, 2004–2005, 2007, and 2010–2011. Because of attrition in the original cohort, in 2004, a new cohort of 902 individuals who were the same age as the original cohort (75 or older at the time) was added to increase sample size and statistical power. This new panel was re-contacted in 2007 and 2010–2011. We use aggregated individual-level data from 1993–2011 to obtain prevalence estimates across survey years with a mortality linkages through NDI up to December 31, 2011. Respondents ranged in age from 65 to 107 years. The final analytic sample includes 3,952 unique individuals and 35,701 person-years of data.

Measures

Disability refers to limitations in performance of social roles and tasks in the context of the socio-cultural and physical environment (Spector & Fleishman, 1998). Respondents were given a detailed interview about demographic characteristics, health status, impairments, and disabilities. Measures of disability included ADLs and IADLs. The survey measured seven ADL activities: walking across a small room (8-foot walk), bathing (either a sponge bath, tub, or shower), dressing (putting on a shirt, buttoning or zipping, or putting on shoes), eating (holding a fork, cutting food, or drinking from a glass), transferring from a bed to a chair, personal grooming (brushing hair), and using the toilet (Branch, Katz, Kniepmann, & Papsidero, 1984; Katz et al., 1963). For each of the seven items, respondents were asked to indicate whether they could perform the activity without help, with help, or whether they were unable to do so. ADL disability was dichotomized as no help needed versus needing help with or unable to perform one or more of the tasks. A positive response was coded as an ADL limitation.

IADLs (Fillenbaum, Hughes, Heyman, George, & Blazer, 1998; Lawton & Brody, 1969; Rosow & Breslau, 1966) are self-report measures commonly used in studies that assess basic activities necessary to reside in the community. Similar to the ADLs, IADLs are intended to identify elderly individuals who are having difficulty performing important activities of living and may be at risk for loss of independence in the community (Ostir & DiNuzzo, 2003). Ten IADL activities were measured: preparing meals, doing heavy housework (wash windows, wall, and floors), walk up and down the stairs without help, doing light housework (dishwashing, bed making, etc.), shopping, managing money, taking medicines, telephoning, going places outside of walking (driving car or traveling on bus or taxi), and walk a half mile without help. Respondents were asked to indicate whether they could perform the activity without help or whether they were unable to do the activity at all. IADL disability was dichotomized as no help needed versus unable to perform one or more of the tasks. A positive response was coded as an IADL limitation.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

We include several known socio-demographic correlates of health status in our descriptive analysis, including age, sex, marital status, educational attainment, number of children, social support, living arrangements, and health status. Age is a continuous variable, ranging from 65 to 107. Marital status is coded as 1 for unmarried and as 0 otherwise. Education is a continuous variable. Our measurement of social support is measured by two items: emotional and instrumental support. Respondents were asked, “In times of trouble, can you count on at least some of your family or friends?” Respondents were also asked, “Can you talk about your deepest problems with at least some of your family or friends?” Response categories for these items were coded 0 = hardly ever/some of the time or 1 = most of the time. We include three dichotomies based on living arrangements. The categories are (a) married with spouse for those married individuals who are living with their spouse only, (b) married with family for married individuals who are living with their spouse and some other family member, and (c) alone for single individuals with no family members living with them.

We used the performance-oriented mobility assessment (POMA) to assess functional mobility. The POMA is based on three tasks: standing balance (semi-tandem and side by side), a timed 8-ft walk at a normal pace (gait speed), and a timed test of five repetitions of rising from a chair and sitting down (Guralnik, Ferrucci, Simonsick, Salive, & Wallace, 1995). Each assessment was coded 0 = unable to complete task, 1 = poor, 2 = moderate, 3 = good, and 4 = best. Respondents who received a score of 0 on at least one POMA’s item are coded as having a POMA disability.

Our assessment of chronic conditions is based on a summative measure of six self-reported items that asked whether the respondent had ever been told by a doctor or other medical personnel that he or she had any of the conditions. Respondents were asked whether they had ever had (a) arthritis or rheumatism; (b) diabetes, sugar in your urine, or high blood sugar; (c) high blood pressure; (d) a heart attack, or coronary, or myocardial infarction, or coronary thrombosis; (e) a stroke, a blood clot in the brain, or a brain hemorrhage; or (f) cancer or a malignant tumor of any type.

We use two measures of immigration status. To classify nativity, we use birth place information and categorize those respondents born in the United States versus born in Mexico. To measure life course stage at migration, we include three ages at immigration groups: those who arrived in childhood (0–19 years), middle age (20–49 years), and those who arrived in later life (after age 50).

Acculturation is measured in terms of three questions: In your opinion, how well do you (a) Understand spoken English, (b) Speak English, and (c) Read English. For each of the three items respondents were asked to indicate whether they could perform the activity: (a) not at all, (b) not too well, (c) pretty well, or (d) very well. A scale was developed to measure level of acculturation. Respondents who scored less than six are coded as having low acculturation, respondents who scored six or higher are coded as having medium/high acculturation.

Statistical Analysis

The study combines age-specific mortality rates with age-specific prevalence of ADL and IADL disabilities to calculate Sullivan-based multistate life table models of ADL and IADL disabilities free and life expectancy with ADL and IADL for each group (Sullivan, 1971). This technique is a prevalence-based method of estimating healthy life expectancy. This method divides total life expectancy into the different health states based on the age-specific prevalence of disabled (with ADL and IADL) and non-disabled (ADL and IADL free) states.

To estimate mortality rates, Gompertz models of the following form stratified by sex and nativity are used.

| (1) |

where, x is age, m(x) is age-specific mortality rate, β0 is the constant term, and β1 is the coefficient for age (Teachman & Hayward, 1993).

To estimate prevalence probability, the logistic regressions of the following form stratified by sex and nativity are fitted.

| (2) |

where, π is the prevalence probability.

By using Equation 1, age-specific mortality rates can be estimated, and total life expectancy is obtained. From Equation 2, the age-specific prevalence of ADL and IADL is obtained. The estimated prevalence is used to divide total life expectancy into the different health states based on the age-specific prevalence of disabled (with ADL and IADL) and non-disabled (ADL and IADL free) states. Disabled/non-disabled life expectancy calculated by this method is the number of remaining years (at a specific age) that a population can expect to live in a disabled/non-disabled state (Jagger, Cox, Le Roy, & European Health Expectancy Monitoring Unit, 2006). For additional detail, please refer to Jagger et al. (2006).

A bootstrapping technique is used here to obtain standard errors for the total life expectancy, healthy life expectancy, and unhealthy life expectancy. Bootstrapping generates repeated estimates of the healthy life expectancy by randomly drawing a series of bootstrap samples from the analytic samples. Repeating this approach for 300 times, distributions of the total life expectancy, healthy life expectancy and unhealthy life expectancy are obtained, which allow us to estimate sampling variability for the total life expectancy, healthy life expectancy and unhealthy life expectancy. Based on the 300 life tables for a given group, confidence intervals were obtained for the distributions of the total life expectancy, healthy life expectancy, and unhealthy life expectancy for that group. Statistical significant tests can be performed according to the confidence intervals.

We use the formula below to calculate confidence intervals:

| (3) |

Where X is total life expectancy, healthy life expectancy, unhealthy life expectancy, or ratio of healthy to total life expectancy. SE is the standard error of X The 95%, 99%, and 99.9% confidence intervals can be obtained by using α = 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively.

Results

ADL Active Life Expectancy

Table 1 presents estimates of life expectancy for men and women at age 65, as well as the average number of years spent with and without any ADL disability. The analysis is stratified by nativity to determine whether an immigrant advantage emerges. Overall life expectancy for the foreign-born is modestly higher than the native-born. Among women, total life expectancy at age 65 is slightly higher (18.9 years) for the foreign-born than for the native-born (17.8 years), although the difference is not statistically significant. Likewise, no statistically significant differences emerge in ALE (13.5 vs. 14.0 years). However, foreign-born women experience a significantly higher (p < .01) number of elderly years spent with ADL disability than native-born women (4.9 vs. 4.3 years). Similarly, there are statistically significant differences (p < .01) in the ratio of number of years lived with ADL disability to the total number of years lived. The results indicate that foreign-born women spend 74% of their remaining years after age 65 in a healthy state compared with 76% for native born.

Table 1.

ADL and IADL Active Life Expectancy at Age 65 by Nativity and Gender.

| ADL

|

IADL

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native-born

|

Foreign-born

|

Native-born

|

Foreign-born

|

|

| Years (SE) | Years (SE) | Years (SE) | Years (SE) | |

| Females | ||||

| Total life expectancy | 17.8 (0.32) | 18.9 (0.39) | 17.8 (0.32) | 18.9 (0.39) |

| ALE | 13.5 (0.27) | 14.0 (0.30) | 7.2 (0.21) | 5.5 (0.23)*** |

| Disabled life expectancy | 4.3 (0.16) | 4.9 (0.21)** | 10.8 (0.26) | 13.4 (0.35)*** |

| Ratio of active to total | 0.76 (0.01) | 0.74 (0.01)** | 0.40 (0.01) | 0.29 (0.01)*** |

| Males | ||||

| Total life expectancy | 15.3 (0.32) | 16.5 (0.45)* | 15.3 (0.32) | 16.5 (0.45)* |

| ALE | 12.5 (0.30) | 13.9 (0.40)* | 8.6 (0.25) | 8.8 (0.31) |

| Disabled life expectancy | 2.7 (0.15) | 2.6 (0.15) | 6.7 (0.23) | 7.6 (0.29)** |

| Ratio of active to total | 0.82 (0.01) | 0.84 (0.01) | 0.56 (0.01) | 0.54 (0.01) |

Source. Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly (H-EPESE) Waves 1 to 7.

Note. ADL = Activities of Daily Living; IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; ALE = Active Life Expectancy.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001 (nativity differentials).

A different pattern emerges for men. The foreign-born have a significant advantage (p < .05) in total life expectancy over the native-born. Results show that at age 65, foreign-born males can expect to live an additional 16.5 years compared with 15.3 years for the native-born. Furthermore, foreign-born males spend a greater amount of time healthy (13.9 vs. 12.5 years) than the native-born (p < .05). Conversely, no statistically significant differences emerge in the number of years spent with ADL disability. In addition, Table 1 shows that the ratio of the number of years lived with ADL disability to the total number of years lived is largely similar for foreign-born and native-born men (84% vs. 82%, respectively).

IADL Active Life Expectancy

The third and fourth columns of Table 1 present estimates of life expectancy for men and women at age 65, as well as the average number of years spent with and without any IADL disability. Life expectancy for both foreign-born and native-born Mexican elderly men and women are identical to the previous analysis. Among women, ALE at age 65 is 5.5 years for the foreign-born compared with 7.2 years for the native-born (p < .001). Foreign-born women also spend a larger fraction of their elderly years with IADL disability than native-born women (13.4 vs. 10.8 years; p < .001). Furthermore, Table 1 reveals statistically significant differences (p < .001) in the ratio of number of years lived with IADL disability to the total number of years lived. Foreign-born women spend 29% of their remaining years after age 65 in a healthy state compared with 40% for native-born.

For men, a slightly different pattern emerges. The foreign-born spend a significantly larger number of years with IADL disability than the native-born (7.6 vs. 6.7 years). In addition, the ratio of number of elderly years lived with IADL disability to the total number of years lived is slightly lower for foreign-born men compared with native-born men. Foreign-born men spend 54% of their remaining years in a healthy state compared with 56% for native-born men. Conversely, there are no statistically significant differences in ALE among foreign-born and native-born men.

Wave 1: Demographic characteristics

Table 2 presents demographic and health characteristics of the sample. The analyses compare differences in ADL disability and IADL disability by nativity and level of acculturation separately for men and women. In the first half of the table, the data reveal that regardless of nativity, women with low acculturation reported fewer years of education. Similar patterns are observed for men. There were no statistically significant differences for marital status by acculturation. Lower acculturated native-born women are slightly older than medium-high acculturated native-born women (p < .01). Highly acculturated native-born men were more likely to live alone than low-acculturated foreign-born men or with their spouse only or in an extended household. Regardless of nativity, low-acculturated men and women report more children than medium-high acculturated men and women. In terms of immigration factors, foreign-born men and women with low acculturation were more likely than the medium-high acculturated foreign-born to have arrived in the United States in later life. Conversely, among the foreign-born, those with medium and high levels of acculturation were more likely to have immigrated in childhood, although substantial fractions arrived in mid-late-life.

Table 2.

Demographic and Health Characteristics Comparing Low Versus

| Nativity acculturation |

Females

|

Males

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native-born

|

Foreign-born

|

Native-born

|

Foreign-born

|

|||||

| Low | Medium/High | Low | Medium/High | Low | Medium/High | Low | Medium/High | |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age (M) | 72.9 | 72.0** | 73.9 | 73.6 | 72.2 | 71.8 | 73.4 | 74.8 |

| Education (M years) | 2.4 | 7.0*** | 3.2 | 5.6*** | 2.9 | 7.2*** | 2.1 | 5.2*** |

| Marital status (married) | 43.9 | 45.8 | 39.9 | 37.0 | 63.9 | 74.8 | 75.0 | 77.7 |

| Number of children | 5.7 | 4.5*** | 5.1 | 4.4* | 5.0 | 4.4* | 6.3 | 5.6* |

| Life course stage at migration | ||||||||

| Childhood | — | — | 17.2 | 38.2*** | — | — | 19.9 | 34.3*** |

| Mid life | — | — | 52.4 | 49.1*** | — | — | 56.5 | 50.0*** |

| Late life | — | — | 30.4 | 12.7*** | — | — | 23.6 | 15.8*** |

| Social support | ||||||||

| Emotional support (most of the time) | 76.3 | 74.8 | 73.4 | 61.3* | 71.5 | 68.2 | 76.3 | 63.3* |

| Instrumental support (most of the time) | 75.8 | 79.1 | 76.2 | 61.8* | 69.2 | 70.9 | 78.3 | 66.6 |

| Living arrangements | ||||||||

| Spouse only | 28.9 | 29.5 | 22.6 | 20.8 | 37.9 | 45.4* | 31.5 | 39.9 |

| Spouse/others | 42.0 | 41.4 | 51.2 | 45.7 | 34.7 | 42.0* | 56.0 | 47.1 |

| Alone | 29.1 | 29.1 | 26.2 | 33.5 | 27.5 | 12.6* | 12.5 | 13.1 |

| Health | ||||||||

| Any ADL | 9.7 | 7.0 | 12.7 | 11.6 | 7.1 | 8.1 | 9.3 | 9.7 |

| Any IADL | 60.8 | 50.0** | 77.1 | 61.9** | 43.6 | 34.8* | 50.9 | 44.0** |

| Limited physical mobility (POMA) | 76.1 | 59.2*** | 60.3 | 65.2 | 62.5 | 53.9 | 45.7 | 56.9 |

| Chronic conditions (M) | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| N | 239 | 661 | 416 | 258 | 132 | 503 | 252 | 244 |

Source. Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly (HEPESE) Wave 1.

Note. These data have been inflated using person weights to obtain sample estimates. ADL = Activities of Daily Living; IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; POMA = performance-oriented mobility assessment.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

The second half of Table 2 shows that less acculturated foreign-born men and women report more emotional support than medium and highly acculturated foreign-born women (p < .05). A similar pattern is revealed in needing instrumental support for low-acculturated foreign-born women. Finally, there were few differences in health and self-reported ADL across acculturation groups for both men and women. However, there were statistically significant differences for both men and women in regard to lower acculturated scores among the foreign-born reporting at least one IADL disability. Less acculturated foreign-born women were also more likely than the native-born with low acculturation scores to report a function limitation (POMA). Although less acculturated foreign-born women report more family to rely on for support, they also report a greater need for assistance in terms of IADL disability and functional limitations. Ancillary analyses reveal that foreign-born women with low acculturation reported at least one IADL disability (59.1%). Altogether, our findings reveal that acculturation interacts with nativity across all measures of social, demographic, and health characteristics at the Wave 7 follow-up.

Wave 7: Immigration characteristics

Table 3 presents immigration-related characteristics of survivors and the deceased at wave 7 separately for men and women. The table compares six outcomes: no ADL disability, at least one ADL disability, and deceased, no IADL disability, at least one IADL disability, and deceased by nativity. For women, the data reveal that mid-life immigrants (20–49 years old) were more likely to have died at the last follow-up. There were no statistically significant differences across groups in level of acculturation. Similar patterns in mortality were observed among mid-life migrant men. Although women are more likely than men to have survived by Wave 7, they also report having at least one ADL and/or one IADL.

Table 3.

Immigration-Related Characteristics of Survivors and Deceased at Wave 7.

| NoADL

|

ADL

|

Deceased

|

No IADL

|

IADL

|

Deceased

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native born |

Foreign born |

Native born |

Foreign born |

Native born |

Foreign born |

Native born |

Foreign born |

Native born |

Foreign born |

Native born |

Foreign born |

|

| Females | ||||||||||||

| Life course stage at migration | ||||||||||||

| Childhood | — | 19 9** | — | 16.7** | — | 28.5** | — | 0.0** | — | 19 1** | — | 28.5** |

| Mid life | — | 56.1** | — | 53.1** | — | 51.7** | — | 100.0** | — | 51.7** | — | 51.7** |

| Late life | — | 24.0** | — | 30.2** | — | 19.8** | — | 0.0** | — | 29 2** | — | 19.8** |

| Acculturation | ||||||||||||

| Low | 15.9** | 44.3 | 34.3** | 61.1 | 23.1** | 52.6 | 8.5 | 29.4* | 24.1 | 55.4* | 23.1 | 52.6* |

| Medium/high | 84.1** | 55.7 | 65.7** | 38.9 | 76.9** | 47.4 | 91.5 | 70.6* | 75.9 | 44.6* | 76.9 | 47.4* |

| N | 107 | 64 | 105 | 87 | 601 | 439 | 26 | 10 | 186 | 141 | 601 | 439 |

| Males | ||||||||||||

| Life course stage at migration | ||||||||||||

| Childhood | — | 9.3* | — | 29.8* | — | 28.8* | — | 1 1.3* | — | 17.4* | — | 28.8* |

| Mid life | — | 67.5* | — | 57.2* | — | 49.4* | — | 63.1* | — | 64.6* | — | 49.4* |

| Late life | — | 23.3* | — | 12.9* | — | 21.8* | — | 25.6* | — | 18.0* | — | 21.8* |

| Acculturation | ||||||||||||

| Low | 18.7 | 47.0 | 22.3 | 62.9 | 17.4 | 51.4 | 13.1 | 45.6 | 23.0 | 55.0 | 17.4 | 51.4 |

| Medium/high | 81.3 | 53.0 | 77.7 | 37.1 | 82.6 | 48.6 | 86.9 | 54.5 | 77.0 | 45.0 | 82.6 | 48.6 |

| N | 62 | 52 | 34 | 37 | 486 | 359 | 31 | 19 | 65 | 70 | 486 | 359 |

Source. Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly (H-EPESE) Wave 7.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Summary and Discussion

While previous research has focused on comparing ALE across racial and ethnic groups, few studies have focused specifically on disabled and non-disabled life expectancy outcomes within Mexican-origin elders residing in the United States. Our findings are consistent with the literature that foreign-born individuals residing in the United States have lower mortality than their native-born peers (Singh & Hiatt, 2006). Although foreign-born Mexican elderly live longer, they are doing so in a disabled state. Foreign-born women in particular spend a larger fraction of their elderly years with both ADL and IADL disability compared with native-born women. Foreign-born males also spend a significantly larger fraction of their elderly lives with IADL disability compared with native-born men. However, they also spend a significantly larger fraction of non-disabled years ADL free. High rates of IADL disability among foreign-born men and women may be attributed largely to the problems they encounter with driving or obtaining transportation, areas in which they are clearly handicapped (J. L. Angel, Angel, McClellan, & Markides, 1996).

The descriptive analyses reveal the important role that acculturation plays in disability. Foreign-born women who were categorized as less acculturated if they lacked English language proficiency reported a greater number of IADLs than foreign-born women with higher acculturation scores. Similarly, less acculturated native-born women resemble the low-acculturated foreign-born. Men manifest similar patterns. What these results clearly reveal is that acculturation interacts with nativity and that lower acculturation scores magnify the disparity in IADL disability for foreign-born men and women. Our measure of acculturation is based on language proficiency and use, and consequently reflects both a cultural orientation and social competence. By social competence we mean the ability to function in a new linguistic environment. The data reveal that higher levels of acculturation, defined in terms of language proficiency, are associated with higher levels of education. This association raises the possibility that the two are confounded and that our language proficiency and education co-vary in a potentially complex manner. More education probably improves one’s language ability. Of course, proficiency in English is probably affected by the country in which the education was obtained. The greater the fraction of education obtained in the United States, the more likely one is to have mastered English.

Our findings underline the importance of considering acculturation when planning for health interventions to address the needs of the growing Mexican elder population. Specifically, the results regarding the lack of linguistic competency highlight the important implications for healthy aging. As recent research shows, low acculturation magnifies health disparities in diabetes and other disabling chronic illnesses (Afable-Munsuz, Gregorich, Markides, & Pérez-Stable, 2013). Moreover, limited English proficiency is linked to major barriers in access to medical and social services (Mutchler & Brallier, 1999). Although the majority of individuals in the H-EPESE cohort report medium to high acculturation, those with low acculturation scores clearly are at risk for dependency on family and formal supports. This issue merits special attention in the development of community-based long-term care programs to appropriately target the specific needs of different sub-groups of older individuals of Mexican-origin who are entering into their last decades of life.

In conclusion, lower mortality among foreign-born Mexican-origin elderly individuals is not matched by low disability rates (Cantu et al., 2013; Eschbach, Al-Snih, Markides, & Goodwin, 2007; Hayward, Hummer, Chiu, Gonzales, & Wong, 2014; Markides et al., 2007). Extended life expectancy of foreign-born Mexican elderly in the United States is accompanied by a lengthy period of disability, particularly for foreign-born females. Given the rapid aging of the older Mexican-origin population and their relatively long life spans, public health interventions designed to prevent functional disability merit serious attention.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: We gratefully acknowledge financial support for this research provided by the NIH National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01 MD005894-01) , the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG10939-10), and the University of Texas Population Research Center (grant R24 HD42849).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abraido-Lanza AF, Armbrister AN, Florez KR, Aguirre AN. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1342–1346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afable-Munsuz A, Gregorich SE, Markides KS, Pérez-Stable EJ. Diabetes risk in older Mexican Americans: Effects of language acculturation, generation and socioeconomic status. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2013;28:359–373. doi: 10.1007/s10823-013-9200-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel JL, Angel RJ, McClellan JL, Markides KS. Nativity, declining health, and preferences in living arrangements among elderly Mexican Americans: Implications for long-term care. The Gerontologist. 1996;36:464–473. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.4.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel JL, Torres-Gil F, Markides K, editors. Aging, health, and longevity in the Mexican-origin population. New York, NY: Springer Sciences; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Angel RJ, Angel JL. Hispanic families at risk: The new economy, work, and the welfare state. New York, NY: Springer Sciences; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Angel RJ, Angel JL, Hill T. Longer life, sicker life? Increased longevity and extended disability among Mexican-origin elders. The Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences. 2014 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu158. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias E. United States life tables by Hispanic origin vital and health statistics (Vol. 152, Table G) Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias E. United States life tables, 2008 (National Vital Statistics Reports) Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baca Zinn M, Pok AYH. Tradition and transition in Mexican-origin families. In: Taylor RL, editor. Minority families in the United States. 3rd. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2002. pp. 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas G. Gender and assimilation among Mexican Americans. In: Blau FD, Kahn LM, editors. Mexican immigration to the United States (Vol. ER Working Paper No. 11512) Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Branch LG, Katz S, Kniepmann K, Papsidero JA. A prospective-study of functional status among community elders. American Journal of Public Health. 1984;74:266–268. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantu P, Hayward MD, Hummer RA, Chiu C-T. New estimates of racial/ethnic differences in life expectancy with chronic morbidity and functional loss: Evidence from the National Health Interview Survey. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2013;28:283–297. doi: 10.1007/s10823-013-9206-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu C-J, Wray LA. Physical disability trajectories in older Americans with and without diabetes: The role of age, gender, race or ethnicity, and education. The Gerontologist. 2011;51:51–63. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins EM, Hayward MD, Seeman TE. Race/ethnicity, socio-economic status, and health. In: Anderson NB, Bulatao RA, Cohen B, editors. Critical perspectives on racial and ethnic differences in health in late life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. pp. 310–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschbach K, Al-Snih S, Markides KS, Goodwin JS. Disability and active life expectancy of older U.S.-and foreign-born Mexican Americans. In: Angel JL, Whitfield KE, editors. The health of aging Hispanics: The Mexican-origin population. New York, NY: Springer; 2007. pp. 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Fillenbaum GG, Hughes DC, Heyman A, George LK, Blazer DG. Relationship of health and demographic characteristics to mini-mental state examination score among community residents. Psychological Medicine. 1988;18:719–726. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700008412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass TA. Conjugating the “tenses” of function: Discordance among hypothetical, experimental, and enacted function in older adults. The Gerontologist. 1998;38:101–112. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;332:556–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward MD, Hummer RA, Chiu C, Gonzales C, Wong R. Does the Hispanic paradox in mortality extend to disability? Population Research and Policy Review. 2014;33:81–96. doi: 10.1007/s11113-013-9312-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward MD, Warner DF, Crimmins EM. Does longer life mean better health? Not for native-born Mexican Americans in the health and retirement study. In: Angel JL, Whitfield KE, editors. The health of aging Hispanics: The Mexican-origin population. New York, NY: Springer; 2007. pp. 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Jagger C, Cox B, Le Roy S. European Health Expectancy Monitoring Unit. Health expectancy calculation by the Sullivan method (EHEMU Technical Report) 2006 Retrieved from http://www.eurohex.eu/pdf/Sullivan_guide_final_jun2007.pdf.

- Kane RA, Kane RL, Ladd RC. The heart of long-term care. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G, Worley CB, Allen RS, Vinson L, Crowther MR, Parmelee P, Chiriboga DA. Vulnerability of older Latino and Asian immigrants with limited English proficiency. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011;59:1246–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EP. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch SM, Brown JS, Harmsen KG. The effect of altering ADL thresholds on active life expectancy estimates for older persons. The Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological & Social Sciences. 2003;58:S171–S178. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.3.s171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS, Eschbach K, Ray LA, Peek MK. Census disability rates among older people by race/ethnicity and type of Hispanic origin. In: Angel JL, Whitfield KE, editors. The health of aging Hispanics. New York, NY: Springer; 2007. pp. 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS, Rudkin L, Angel RJ, Espino D. Health status of Hispanic elderly. In: Martin LG, Soldo BJ, editors. Racial and ethnic differences in the health of older Americans. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1997. pp. 285–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Osterman MJK, Wilson EC, Mathews TJ. Births: Final data for 2010 (National Vital Statistics Report, Vol. 61, No. 1) 2012 Retrieved from http://waterbirthsolutions.com/Downloadables/1.pdf. [PubMed]

- Minicuci N, Noale M, Pluijm SMF, Zunzunegui MV, Blumstein T, Deeg DJH, Jylhä M. Disability-free life expectancy: A cross-national comparison of six longitudinal studies on aging. The CLESA project. European Journal on Aging. 2004;1:37–44. doi: 10.1007/s10433-004-0002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutchler JE, Brallier S. English language proficiency among older Hispanics in the United States. The Gerontologist. 1999;33:310–319. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostir GV, DiNuzzo T. In: Resource book of the Hispanic established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. Black Sandra A, Ray Laura A, Angel Ronald J, Espino David V, Miranda Manuel, Markides Kyriako S., editors. Ann Arbor, MI: National Archive for Computerized Data on Aging; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Palloni A, Arias E. Paradox lost: Explaining the Hispanic adult mortality advantage. Demography. 2004;41:385–415. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrado EA, Flippen CA. Migration and gender among Mexican women. American Sociological Review. 2005;70:606–632. [Google Scholar]

- Peek MK, Ottenbacher KJ, Markides KS, Ostir GV. Examining the disablement process among older Mexican American adults. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57:413–425. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00367-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek MK, Patel K, Ottenbacher KJ. Expanding the disablement process model among older Mexican Americans. The Journal of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences. 2005;60:M334–M339. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosow I, Breslau N. A Guttman health scale for the aged. Journal of Gerontology. 1966;21:556–559. doi: 10.1093/geronj/21.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh GK, Hiatt RA. Trends and disparities in socioeconomic and behavioural characteristics, life expectancy, and cause-specific mortality of native-born and foreign-born populations in the United States, 1979–2003. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;35:903–919. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector WD, Fleishman JA. Combining activities of daily living with instrumental activities of daily living to measure functional disability. The Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological & Social Sciences. 1998;53:S46–S47. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.1.s46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan DF. A single index of mortality and morbidity. HSMHA Health Reports. 1971;86(4):347–354. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teachman JD, Hayward MD. Interpreting hazard rate models. Sociological Methods & Research. 1993;21:340–371. [Google Scholar]

- Werner CA. The older population: 2010. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-09.pdf.

- Wiener JM, Hanley RJ, Clark R, Nostrand JFV. Measuring the activities of daily living: Comparisons across national surveys. Journal of Gerontology. 1990;45:S229–S237. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.6.s229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]