Abstract

Rationale

Therapies which inhibit cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) have failed to demonstrate a reduction in risk for coronary heart disease (CHD). Human deoxyribonucleic acid sequence variants that truncate the CETP gene may provide insight into the efficacy of CETP inhibition.

Objective

To test whether protein truncating variants (PTVs) at the CETP gene were associated with plasma lipid levels and CHD.

Methods and Results

We sequenced the exons of the CETP gene in 58,469 participants from 12 case-control studies (18,817 CHD cases, 39,652 CHD-free controls). We defined PTV as those that lead to a premature stop, disrupt canonical splice-sites, or lead to insertions/deletions that shift frame. We also genotyped one Japanese-specific PTV in 27,561 participants from three case-control studies (14,286 CHD cases, 13,275 CHD-free controls). We tested association of CETP PTV carrier status with both plasma lipids and CHD. Among 58,469 participants with CETP gene sequencing data available, average age was 51.5 years and 43% were female; 1 in 975 participants carried a PTV at the CETP gene. Compared to non-carriers, carriers of PTV at CETP had higher high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C; effect size, 22.6 mg/dL; 95% confidence interval [CI], 18 to 27; P < 1.0×10−4), lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C; −12.2 mg/dL; 95% CI, −23 to −0.98; P = 0.033), and lower triglycerides (−6.3%; 95% CI, −12 to −0.22, P = 0.043). CETP PTV carrier status was associated with reduced risk for CHD (summary odds ratio, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.54 to 0.90; P = 5.1×10−3).

Conclusions

Compared with non-carriers, carriers of PTV at CETP displayed higher HDL-C, lower LDL-C, lower triglycerides, and lower risk for CHD.

Keywords: Cholesteryl ester transfer protein, exome sequencing, protein truncating variants, coronary heart disease, genetics, human, lipids

Subject Terms: Genetics, Lipids and Cholesterol, Coronary Artery Disease

INTRODUCTION

In three randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs), therapies which inhibit cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) have failed to demonstrate a reduction in risk for coronary heart disease (CHD).1–3 Possible reasons for this failure include on-target lack of efficacy, off-target adverse effects of the small molecule, and/or randomized controlled trial design factors such as insufficient statistical power, concurrent statin therapy, or selection of study participants.4–6 A randomized trial of a fourth CETP inhibitor – anacetrapib – is ongoing.7

Studies of humans with naturally occurring genetic variation in genes encoding drug targets can provide insight into the potential efficacy and safety of therapeutic modulation targeting the gene product.8–10 Genetic studies of common, regulatory variants at the CETP gene region initially showed mixed results,11–15 but more recently, have converged on a consensus finding: alleles with lower CETP expression are associated with reduced CHD risk.16

Beyond common deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequence variants, rare mutations that truncate a therapeutic target gene may be of particular value because they most closely mirror pharmacologic inhibition.8, 9, 17 Indeed, protein truncating variants (PTVs; i.e., nonsense, canonical splice-site, and frameshift mutations) at two therapeutic targets – NPC1 Like Intracellular Cholesterol Transporter 1 (NPC1L1)9 and Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 (PCSK9)8 – are associated with lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and reduced CHD risk. A therapeutic trial testing NPC1L1 inhibition was consistent with the human genetic findings,18 and a trial testing PCSK9 inhibition was consistent as well.19 Here, we tested if rare PTVs at the CETP gene were associated with plasma lipids and reduced odds of CHD.

METHODS

Study participants

First, we sequenced a total of 58,469 participants from the Myocardial Infarction Genetics (MIGen) Consortium of African, European, and South Asian ancestries (N=25,273), the DiscovEHR project of the Regeneron Genetics Center and the Geisinger Health System (DiscovEHR) of European ancestry (N=24,138),20 and TAICHI Consortium of East Asian ancestry (N=9,058)21 (Table 1). The MIGen Consortium consists of the Italian Atherosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology (ATVB) Study22, the Deutsches Herzzentrum München Myocardial Infarction Study (DHM)9, the Exome Sequencing Project Early-Onset Myocardial Infarction Study (ESP-EOMI)23, 24 of European and African ancestries, the Jackson Heart Study (JHS),25 the Leicester Acute Myocardial Infarction Peptide Study (Leicester),26 the Lübeck Myocardial Infarction Study (Lubeck),27 the Ottawa Heart Study (OHS),28 the Precocious Coronary Artery Disease Study (PROCARDIS),29 the Pakistan Risk of Myocardial Infarction Study (PROMIS),30 and the Registre Gironi del COR (REGICOR) Study.31

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of each study by protein truncating variant carrier status.

| MIGen | DiscovEHR | TAICHI | BBJ | CAGE-CAD Stage1 | CAGE-CAD Stage2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTV carrier | Non- carrier |

PTV carrier |

Non- carrier |

PTV carrier |

Non- carrier |

PTV carrier |

Non- carrier |

PTV carrier |

Non- carrier |

PTV carrier |

Non- carrier |

|

| N = 26 | N = 25,247 | N = 16 | N = 24,122 |

N = 18 | N = 9,040 | N = 122 | N = 15,476 |

N = 21 | N = 2,584 | N = 76 | N = 9,282 |

|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 53.5 (13) | 53.3 (13) | 47.2 (12) | 46.2 (12) | 61.2 (15) | 60.9 (15) | 65.1 (10) | 65.2 (10) | 66.4 (8) | 65.9 (8) | 63.6 (8) | 62.5 (7) |

| Male gender, n (%) | 26 (79) | 18,387 (73) | 9 (56) | 5,777 (24) | 12 (67) | 6,166 (68) | 78 (64) | 10,943 (71) | 12 (57) | 1711 (66) | 48 (63) | 6041 (65) |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 25.7 (23–28) | 26.2 (24–29) | 33.7 (31–38) | 31.2 (26–37) | 24.8 (23–30) | 24.9 (23–28) | 23.2 (21–25) | 23.4 (21–26) | 23.6 (21–24) | 23.3 (21–25) | 23.7 (22–26) | 23.2 (21–24) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 7 (21) | 7,389 (29) | 3 (19) | 5,048 (21) | N/A | N/A | 78 (64) | 10,282 (66) | 11 (52) | 1336 (51) | 36 (47) | 4752 (51) |

| Medical history | ||||||||||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 12 (36) | 9,499 (38) | 7 (44) | 12,933 (54) | 6 (33) | 4,783 (53) | 54 (44) | 6,408 (41) | 6 (28) | 1182 (45) | 39 (51) | 4760 (51) |

| Type 2 Diabetes, n (%) | 8 (24) | 5,069 (20) | 5 (31) | 4,126 (17) | 8 (44) | 4,343 (48) | 78 (64) | 8,568 (55) | 9 (42) | 917 (35) | 16 (21) | 2174 (23) |

| Lipid-lowering medication*, n (%) | 1 (3) | 3,682 (15) | 4 (25) | 6,129 (25) | 3 (19) | 1,781 (22) | 43 (35) | 5,164 (33) | 6 (28) | 377 (14) | N/A | N/A |

| Lipid profile | ||||||||||||

| LDL cholesterol, mean (SD) | 121 (57) | 130 (48) | 114 (39) | 124 (38) | 126 (42) | 120 (50) | 118 (35) | 125 (38) | 117 (32) | 130 (38) | N/A | N/A |

| HDL cholesterol, mean (SD) | 61 (24) | 41 (14) | 58 (14) | 51 (15) | 58 (23) | 45 (14) | 67 (25) | 50 (15) | 78 (24) | 58 (16) | N/A | N/A |

| Triglycerides, median (IQR) | 124 (70–163) | 150 (102–222) | 162 (105–198) | 126 (89–177) | 138 (89–186) | 121 (83–176) | 138 (89–156) | 145 (86–175) | 74 (57–131) | 109 (80–154) | N/A | N/A |

| Total cholesterol, mean (SD) | 211 (61) | 206 (54) | 207 (50) | 205 (42) | 210 (45) | 190 (46) | 239 (72) | 231 (61) | 218 (37) | 214 (41) | N/A | N/A |

At the time of lipid measurement.

Abbreviations: BBJ, BioBank Japan; CAGE-CAD, the Cardio-metabolic Genome Epidemiology Network and Coronary Artery Disease study; DiscovEHR, the DiscovEHR project of the Regeneron Genetics Center and the Geisinger Health System; IQR, interquartile range; MIGen, Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium; N/A, not applicable; PTV, protein truncating variant; TAICHI, TAICHI consortium; SD, standard deviation; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein

We also genotyped a Japanese-specific PTV at the CETP gene (rs5742907; IVS14+1G>A; splice-donor variant32) in a total of 27,561 Japanese participants from BioBank Japan (BBJ)33 and the Cardio-metabolic Genome Epidemiology Network and Coronary Artery Disease (CAGE-CAD) Stage 1 and Stage 2 studies (Table 1).34

All participants in the study provided written informed consent for genetic studies. The institutional review boards at the Broad Institute and each participating institution approved the study protocol.

Definition of CETP protein truncating variants

PTVs were defined as premature stop (nonsense), canonical splice-sites (splice-donor or splice-acceptor) including IVS14+1G>A (rs5742907), or insertion/deletion variants that shifted frame (frameshift). The positions of these PTVs were based on the GRGh37 human genome reference and the canonical transcript for CETP (Transcript ID: ENST00000200676).

Clinical characteristics, lipid measurements, and definition of CHD

A medical history and laboratory data for cardiovascular risk factors were obtained from all the study participants. Plasma total cholesterol, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels were determined enzymatically. LDL-C level was calculated using the Friedewald equation35, 36 for those with triglycerides <400 mg/dL. If triglycerides ≥400 mg/dL, LDL-C level was directly measured, or set to missing. The effect of lipid-lowering therapy at the time of lipid measurement was taken into account by dividing the measured total cholesterol and LDL-C levels by 0.8 and 0.7, respectively.37 HDL-C and triglyceride levels were not adjusted by lipid-altering medication use, and triglyceride levels were natural logarithm transformed for statistical analysis. CHD case and CHD-free control definitions of each study are in Supplemental Table I.

Sequencing and genotyping to characterize protein truncating variants

Whole exome sequencing of the MIGen Consortium was performed at the Broad Institute (Cambridge, MA, USA) as previously described.23 Sequencing reads were aligned to a human reference genome (build 37) using the Burrows–Wheeler Aligner-Maximal Exact Match algorithm. Aligned non-duplicate reads were locally realigned, and base qualities were recalibrated using the Genome Analysis ToolKit (GATK) software.38 Variants were jointly called using the GATK HaplotypeCaller program. The sensitivity of the Variant Quality Score Recalibration threshold was 99.6% for single nucleotide variants and 95% for insertion/deletion variants. All identified variants were annotated with the use of the Variant Effect Predictor software (version 82).39 The DiscovEHR project and TAICHI Consortium participants were exome-sequenced as previously described.20

We also genotyped one splice-donor variant (IVS14+1G>A [rs5742907]) at the CETP gene using the multiplex PCR-based target sequencing in BBJ,40 or the TaqMan assay in CAGE-CAD Stage 1 and Stage 2.

Statistical analysis

We tested the association of CETP PTV carrier status with lipid levels using linear regression adjusted by age, gender, study, and the first five principal components of ancestry (MIGen), or by age and gender (BBJ and CAGE-CAD Stage 1). Only CHD-free controls in each study were included in this assessment to minimize the effect of ascertainment bias. These data were meta-analyzed to calculate overall summary effect sizes with an inverse-variance weighted fixed-effects model.

We tested the association of CETP PTV carrier status with CHD risk using a Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel method without continuous correction. This method combines score statistics instead of Wald statistics and is useful for rare exposures when some observed odds ratios (OR) are zero. We removed ESP-EOMI and JHS from this analysis because no participant in these two studies carried a PTV at the CETP gene.

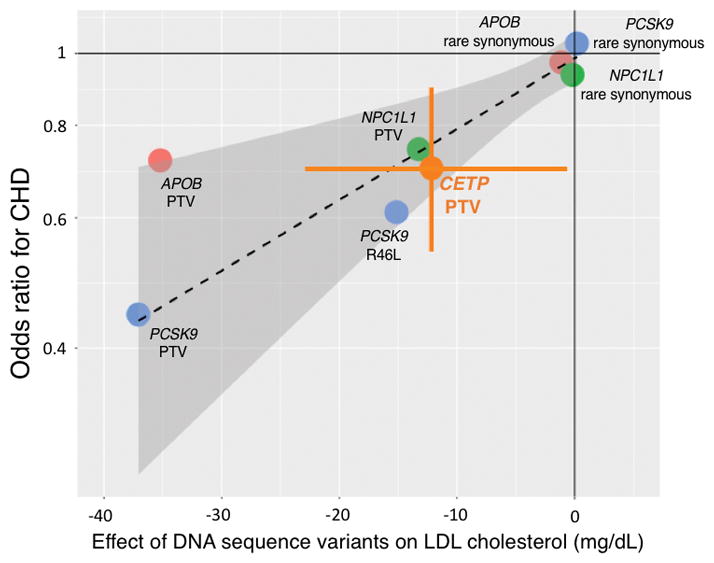

In an exploratory analysis, we evaluated if the effect of CETP PTVs on LDL-C could explain the reduction in CHD risk. We used an inverse-variance weighted model to draw a regression line with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Across four genes (APOB, NPC1L1, PCSK9, and CETP), we plotted the effect of DNA sequence variants in these genes on both LDL-C and CHD risk. The results for APOB, NPC1L1, and PCSK9 are derived from samples of the MIGen Consortium to draw a dose-response reference line. The results for CETP are summary estimate from all studies.

Statistical analyses were performed using R software version 3.2.3 (The R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Prevalence of CETP protein truncating variants

Sequencing of the 16 exons at the CETP gene was performed in 58,469 participants (18,817 CHD cases and 39,652 CHD-free controls) from three projects: the MIGen Consortium, the DiscovEHR project, and TAICHI Consortium. Baseline characteristics of each study are shown in Table 1. A total of 23 PTVs were identified (ten premature stop, nine frameshifts, three splice-donor, and one splice-accepter variants). A total of 60 individuals carried one of the CETP PTVs, including 18 CHD cases (0.096%; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.051 to 0.14%) and 42 CHD-free controls (0.11%; 95% CI, 0.074 to 0.14%). Baseline characteristics by variant carrier status are shown in Supplemental Table II. We genotyped a Japanese-specific splice-donor variant (IVS14+1G>A [rs5742907]) in three studies from Japan and found the carrier frequency to be: BBJ, 0.78%; CAGE-CAD Stage1, 0.81%; and CAGE-CAD Stage2, 0.92%.

Association of CETP protein truncating variants with plasma lipids

We assessed whether CETP PTV carrier status was associated with lipid levels (Table 2 and Supplemental Figure). We obtained plasma lipid profiles in 11,205 control participants from the MIGen Consortium and 6,955 control participants from BBJ and CAGE-CAD Stage 1. CETP PTV carrier status was associated with increased HDL-C (effect size, 22.6 mg/dL; 95% CI, 18 to 27; P < 1×10−4), decreased LDL-C (−12.2 mg/dL; 95% CI, −23 to −0.98; P = 0.033), and decreased triglycerides (−6.3%; 95% CI, −12 to −0.22; P = 0.043).

Table 2.

Associations of CETP protein truncating variant carrier status with HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and total cholesterol.

| MIGen | BBJ + CAGE-CAD | Overall | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect size | 95% CI | P value | Effect size | 95% CI | P value | Effect size | 95% CI | P value | |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 19.2 | 12 to 27 | 2.5 × 10−7 | 24.5 | 19 to 30 | <0.0001 | 22.6 | 18 to 27 | <0.0001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | −20.2 | −45 to 4.8 | 0.11 | −10.2 | −23 to 2.4 | 0.11 | −12.2 | −23 to −0.98 | 0.033 |

| Triglycerides (%) | 2.8% | −27 to 44 | 0.16 | −6.6% | −12 to −0.43 | 0.036 | −6.3% | −12 to −0.22 | 0.043 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 5.2 | −23 to 33 | 0.72 | 8.6 | −8.7 to 26 | 0.97 | 7.6 | −7.1 to 22 | 0.31 |

Abbreviations: BBJ, BioBank Japan; CAGE-CAD, the Cardio-metabolic Genome Epidemiology Network and Coronary Artery Disease study; DiscovEHR, the DiscovEHR project of the Regeneron Genetics Center and the Geisinger Health System; IQR, interquartile range; MIGen, Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium; N/A, not applicable; PTV, protein truncating variant; TAICHI, TAICHI consortium; SD, standard deviation; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein

Association of CETP protein truncating variants with CHD

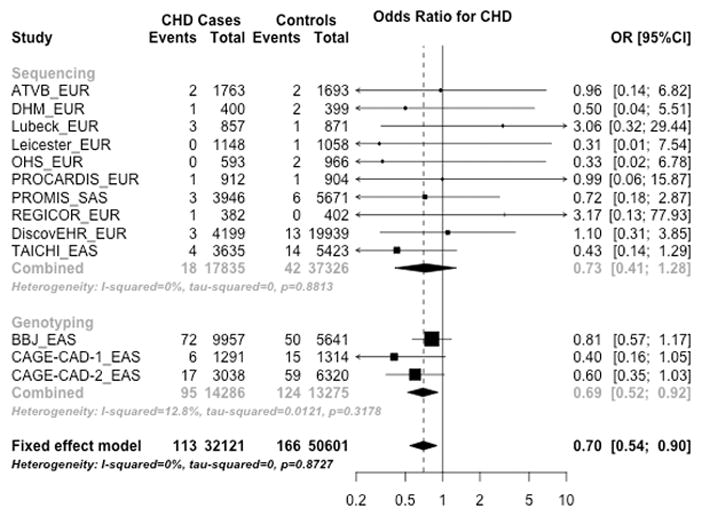

We evaluated the association of CETP PTV carrier status with CHD. Baseline characteristics and lists of CETP PTVs by case-control status in each study are shown in Supplemental Table III and Supplemental Table IV. In an analysis including a total of 82,722 participants, CETP PTV carrier status was significantly associated with lower risk for CHD (summary OR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.54 to 0.90; P = 5.1×10−3) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Association of CETP protein truncating variant carrier status with risk for coronary heart disease.

CETP protein truncating variant carrier status was associated with reduced risk for CHD. Each study column indicates [Study name] _[Ancestry].

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; EAS, East Asian ancestry; EUR, European ancestry; OR, odds ratio; SAS, South Asian ancestry.

DNA sequence variants, LDL-C, and CHD risk across four genes

We explored whether the effect size of CETP PTV on CHD risk was consistent with its effect on LDL-C. We drew a dose-response reference line for CHD risk as a function of LDL-C change conferred by DNA sequence variants in three genes other than CETP. DNA sequence variants in APOB, NPC1L1, and PCSK9 associated with lower LDL-C also correlated with lower CHD risk. The effect of CETP PTV on CHD risk (30% reduction in risk) was consistent with the estimate based on the change in LDL-C (−12.2 mg/dl) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effects of DNA sequence variants in four genes on LDL-C and CHD risk.

Dashed line denotes a dose-response reference line, with the 95% CI indicated by shadow. Error bar indicates CETP PTV 95% CIs of an effect size on LDL-C and odds ratio for CHD.

Abbreviations: CETP, cholesteryl ester transfer protein; CHD, coronary heart disease; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PTV, protein truncating variant.

DISCUSSION

Across more than 80,000 participants, we evaluated whether CETP PTVs were associated with lipid levels and risk for CHD. About 1 in 975 participants carried a PTV at the CETP gene in sequencing studies, and compared with non-carriers, CETP PTV carriers exhibited significantly higher plasma HDL-C levels and lower LDL-C and triglyceride levels. The presence of a CETP PTV was also associated with decreased risk for CHD.

This evidence from rare human mutations that disrupt the CETP gene is consistent with earlier data on common, regulatory variants at the CETP locus. Common variants in the CETP have been associated with increased HDL-C, decreased LDL-C, decreased triglyceride levels,41 and reduced risk for CHD.13, 42–44 And recently, the statistical evidence for association of common CETP variants with CHD has exceeded a stringent genome-wide threshold.16 Exploratory analyses suggest that the effect of CETP PTV on lower CHD risk is consistent with lower LDL-C change conferred by these variants.

If human genetics shows loss of CETP function mutations to be associated with reduced CHD risk, why have three small molecule inhibitors of CETP function all failed to show lower CHD outcomes in randomized clinical trials? Several possibilities emerge. First, this could be due to off-target adverse effects of small molecule inhibitors. Torcetrapib, dalcetrapib, and evacetrapib treatment all led to higher blood pressure in randomized controlled trials1–3; torcetrapib also led to hyperaldosteronism.1

Second, RCT design factors such as limited statistical power could play a role.4, 5 Human genetic evidence is supportive for apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins [low-density lipoprotein, triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, lipoprotein(a)] as causal factors for CHD whereas this is not the case for HDL-C.6 As such, any benefit from CETP inhibition may be solely due to the lowering of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins. On background statin therapy, the LDL cholesterol and apolipoprotein B lowering effect is smaller, as shown in the ACCELERATE trial. 3 As such, it is unclear if RCTs were adequately powered to detect this benefit.

Third, statin therapy may modify the relationship of CETP activity and coronary disease. CETP promotes the transfer of cholesteryl esters from HDL to atherogenic apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins including LDL.4 If not cleared from the circulation, accumulation of such particles in the bloodstream promotes atherosclerotic progression. However, statins lead to substantial upregulation of hepatic LDL receptor density.45 In this context, apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins may be rapidly cleared from the circulation and excreted into the feces. CETP may therefore play a role in promoting reverse cholesterol transport, the process by which cholesterol is extracted from peripheral tissues (e.g. atherosclerotic plaque) and excreted from the body. Indeed, overexpression of CETP leads to enhanced reverse cholesterol transport via a LDL receptor dependent pathway in mouse models.46 Furthermore, individuals with increased on-statin CETP mass were protected from recurrent coronary events, particularly when the achieved LDL cholesterol was less than 80 mg/dl.47 Under this framework, pharmacologic CETP inhibition might prove less effective or potentially harmful among those in whom statin therapy leads to efficient clearance of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins. However, the impact of CETP inhibition on reverse cholesterol transport has been questioned because the mouse studies might have been confounded by cholesterol pool size changes.48 Also, torcetrapib did not elevate fecal cholesterols or bile acids in both on- and off-statin individuals.49

Finally, phenotypic consequences of human PTVs reflect lifelong perturbation of a gene in every human tissue. In contrast, the results of RCTs reflect pharmacologic inhibition initiated later in life. As such, there are intrinsic limitations in using human mutations to anticipate efficacy and safety of pharmacologic manipulation.

These results should be interpreted in the context of study limitations. Definitions of CHD were different among studies. Cases in the MIGen Consortium and the DiscovEHR project were limited to only early-onset CHD while those in East Asian studies were not. Loss of CETP function alters the distribution of cholesterol and triglycerides in lipoproteins and as such, LDL-C levels estimated by the Friedewald equation might overestimate the reduction in participants harboring CETP PTVs. We only assessed four major lipid levels to evaluate effects of CETP PTV carrier status and other traits such as lipoprotein (a) or function of reverse cholesterol transport were unavailable. Results were somewhat stronger in participants from the Japanese genotyping studies, but the point estimates of the OR for CHD were consistent between populations of Japanese and non-Japanese ancestries (0.69 and 0.73, respectively).

Conclusions

In this meta analyses of data from 15 case-control studies, rare PTVs at the CETP gene were associated with higher HDL-C, lower LDL-C, lower triglycerides, and reduced risk for CHD.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is Known?

Human DNA sequence variants that truncate a therapeutic target protein may provide insight into the efficacy of pharmacologic inhibition.

It has been uncertain whether carriers of protein-truncating variants (PTVs) at the cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) gene have altered plasma lipid levels and lower risk for coronary heart disease (CHD).

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Carriers of a PTV at CETP had higher HDL cholesterol, lower LDL cholesterol, and lower triglycerides.

CETP PTV carrier status was also associated with 30% reduced risk for CHD.

Lifelong reduction in CETP function is associated with altered plasma lipids and a lower risk for CHD.

Therapies which inhibit CETP have failed to demonstrate a reduction in risk for CHD. Human DNA sequence variants that truncate a therapeutic target gene may provide insight into the efficacy of pharmacologic inhibition. We tested whether humans carrying PTVs at the CETP gene were associated with lipid levels, and were at reduced risk for CHD. We sequenced the exons of the CETP gene in 58,469 participants from 12 case-control, and genotyped one Japanese-specific PTV in 27561 participants from three case-control studies. PTVs at the CETP gene were defined as mutations that lead to a premature stop, disrupt canonical splice-sites, or lead to insertions/deletions that shift frame. In an analysis including more than 80,000 participants, carriers of a PTV at CETP had higher high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (+22.6 mg/dL), lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (−12.2 mg/dL), and lower triglycerides (−6.3%). CETP PTV carrier status was also associated with 30% reduced risk for CHD (summary odds ratio, 0.70). In conclusion, compared with non-carriers, carriers of PTV at the CETP gene displayed higher HDL-C, lower LDL-C, lower triglycerides, and lower risk for CHD.

Acknowledgments

We thank to all the participants and staffs regarding this project. Also, we express our gratitude to Drs. Toshihiro Tanaka, Yasuhiko Sakata, and Shinichiro Suna for their contribution to the study discussion.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

Dr. Nomura was funded by the Yoshida Scholarship Foundation. Dr. Won was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (No. 2016R1C1B2007920). Dr. Khera is supported by a KL2/Catalyst Medical Research Investigator Training award from Harvard Catalyst funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (TR001100). Dr. Klarin is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of NIH under award number T32 HL007734. Dr. Natarajan is supported by the John S. LaDue Memorial Fellowship in Cardiology from Harvard Medical School. Dr. Kathiresan is supported by the Ofer and Shelly Nemirovsky Research Scholar Award from the Massachusetts General Hospital, the Donovan Family Foundation, and R01 HL127564. Exome sequencing in ATVB, DHM, JHS, OHS, PROCARDIS, and PROMIS was supported by 5U54HG003067 (to Drs. Lander and Gabriel). The JHS is supported and conducted in collaboration with Jackson State University (HHSN268201300049C and HHSN268201300050C), Tougaloo College (HHSN268201300048C), and the University of Mississippi Medical Center (HHSN268201300046C and HHSN268201300047C) contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD). Samples for the Leicester study were collected as part of projects funded by the British Heart Foundation (British Heart Foundation Family Heart Study, RG2000010; UK Aneurysm Growth Study, CS/14/2/30841) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR Leicester Cardiovascular Biomedical Research Unit Biomedical Research Informatics Centre for Cardiovascular Science, IS_BRU_0211_20033). The DiscovEHR project is funded by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CETP

Cholesteryl ester transfer protein

- CHD

Coronary heart disease

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- PTV

Protein truncating variant

- RCT

Randomized controlled clinical trial

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Kathiresan has received grants from Bayer Healthcare, Aegerion Pharmaceuticals, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals; and consulting fees from Merck, Novartis, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Leerink Partners, Noble Insights, Quest Diagnostics, Genomics PLC, and Eli Lilly and Company; and holds equity in San Therapeutics and Catabasis Pharmaceuticals. Other authors have no conflict of interest regarding this study.

References

- 1.Barter PJ, Caulfield M, Eriksson M, et al. Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2109–2122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Abt M, et al. Effects of dalcetrapib in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2089–2099. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholls SJ. Evacetrapib Fails to Reduce Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events. [16 Dec 2016; date last accessed];ACC16. https://www.acc.org/about-acc/press-releases/2016/04/03/13/02/evacetrapib-fails-to-reduce-major-adverse-cardiovascular-events.

- 4.Schaefer EJ. Effects of cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitors on human lipoprotein metabolism: Why have they failed in lowering coronary heart disease risk? Curr Opin Lipidol. 2013;24:259–264. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283612454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamashita S, Matsuzawa Y. Re-evaluation of cholesteryl ester transfer protein function in atherosclerosis based upon genetics and pharmacological manipulation. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2016;27:459–472. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kathiresan S. Will cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibition succeed primarily by lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol? Insights from human genetics and clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2049–2052. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cannon CP, Shah S, Dansky HM, et al. Safety of anacetrapib in patients with or at high risk for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2406–2415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH, Jr, Hobbs HH. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1264–1272. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium Investigators. Stitziel NO, Won HH, et al. Inactivating mutations in NPC1L1 and protection from coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2072–2082. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1405386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kathiresan S the Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium. A PCSK9 missense variant associated with a reduced risk of early-onset myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2299–2300. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0707445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moriyama Y, Okamura T, Inazu A, Doi M, Iso H, Mouri Y, Ishikawa Y, Suzuki H, Iida M, Koizumi J, Mabuchi H, Komachi Y. A low prevalence of coronary heart disease among subjects with increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, including those with plasma cholesteryl ester transfer protein deficiency. Prev Med. 1998;27:659–667. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curb JD, Abbott RD, Rodriguez BL, Masaki K, Chen R, Sharp DS, Tall AR. A prospective study of HDL-C and cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene mutations and the risk of coronary heart disease in the elderly. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:948–953. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300520-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson A, Di Angelantonio E, Sarwar N, Erqou S, Saleheen D, Dullaart RP, Keavney B, Ye Z, Danesh J. Association of cholesteryl ester transfer protein genotypes with CETP mass and activity, lipid levels, and coronary risk. JAMA. 2008;299:2777–2788. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.23.2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirano K, Yamashita S, Nakajima N, Arai T, Maruyama T, Yoshida Y, Ishigami M, Sakai N, Kameda-Takemura K, Matsuzawa Y. Genetic cholesteryl ester transfer protein deficiency is extremely frequent in the omagari area of japan. Marked hyperalphalipoproteinemia caused by CETP gene mutation is not associated with longevity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:1053–1059. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.6.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inazu A, Brown ML, Hesler CB, Agellon LB, Koizumi J, Takata K, Maruhama Y, Mabuchi H, Tall AR. Increased high-density lipoprotein levels caused by a common cholesteryl-ester transfer protein gene mutation. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1234–1238. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011013231803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webb TR, Erdmann J, Stirrups KE, et al. Systematic evaluation of pleiotropy identifies 6 further loci associated with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:823–836. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The TG HDL Working Group of the Exome Sequencing Project, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3, triglycerides, and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:22–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1307095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2387–2397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, Honarpour N, Wiviott SD, Murphy SA, Kuder JF, Wang H, Liu T, Wasserman SM, Sever PS, Pedersen TR for the FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017 Mar 17; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1615664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dewey FE, Gusarova V, O’Dushlaine C, et al. Inactivating variants in ANGPTL4 and risk of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1123–1133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Assimes TL, Lee IT, Juang JM, et al. Genetics of coronary artery disease in taiwan: A cardiometabochip study by the taichi consortium. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0138014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atherosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology Italian Study Group. No evidence of association between prothrombotic gene polymorphisms and the development of acute myocardial infarction at a young age. Circulation. 2003;107:1117–1122. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000051465.94572.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Do R, Stitziel NO, Won HH, et al. Exome sequencing identifies rare LDLR and APOA5 alleles conferring risk for myocardial infarction. Nature. 2015;518:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature13917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study: Design and objectives. The aric investigators. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor HA., Jr The jackson heart study: An overview. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:S6-1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samani NJ, Erdmann J, Hall AS, et al. Genomewide association analysis of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:443–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myocardial Infarction Genetics and CARDIoGRAM Exome Consortia Investigators. Coding variation in ANGPTL4, LPL, and SVEP1 and the risk of coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1134–1144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McPherson R, Pertsemlidis A, Kavaslar N, Stewart A, Roberts R, Cox DR, Hinds DA, Pennacchio LA, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Folsom AR, Boerwinkle E, Hobbs HH, Cohen JC. A common allele on chromosome 9 associated with coronary heart disease. Science. 2007;316:1488–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.1142447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clarke R, Peden JF, Hopewell JC, et al. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2518–2528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saleheen D, Zaidi M, Rasheed A, et al. The pakistan risk of myocardial infarction study: A resource for the study of genetic, lifestyle and other determinants of myocardial infarction in south asia. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24:329–338. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9334-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Senti M, Tomas M, Marrugat J, Elosua R REGICOR Investigators. Paraoxonase1–192 polymorphism modulates the nonfatal myocardial infarction risk associated with decreased HDLs. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:415–420. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inazu A, Jiang XC, Haraki T, Yagi K, Kamon N, Koizumi J, Mabuchi H, Takeda R, Takata K, Moriyama Y. Genetic cholesteryl ester transfer protein deficiency caused by two prevalent mutations as a major determinant of increased levels of high density lipoprotein cholesterol. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1872–1882. doi: 10.1172/JCI117537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konta A, Ozaki K, Sakata Y, Takahashi A, Morizono T, Suna S, Onouchi Y, Tsunoda T, Kubo M, Komuro I, Eishi Y, Tanaka T. A functional SNP in FLT1 increases risk of coronary artery disease in a japanese population. J Hum Genet. 2016 doi: 10.1038/jhg.2015.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeuchi F, Isono M, Katsuya T, Yokota M, Yamamoto K, Nabika T, Shimokawa K, Nakashima E, Sugiyama T, Rakugi H, Yamaguchi S, Ogihara T, Yamori Y, Kato N. Association of genetic variants influencing lipid levels with coronary artery disease in japanese individuals. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clinical chemistry. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warnick GR, Knopp RH, Fitzpatrick V, Branson L. Estimating low-density lipoprotein cholesterol by the friedewald equation is adequate for classifying patients on the basis of nationally recommended cutpoints. Clinical chemistry. 1990;36:15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khera AV, Won HH, Peloso GM, et al. Diagnostic yield and clinical utility of sequencing familial hypercholesterolemia genes in patients with severe hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2578–2589. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLaren W, Pritchard B, Rios D, Chen Y, Flicek P, Cunningham F. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the ensembl API and SNP effect predictor. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2069–2070. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Momozawa Y, Akiyama M, Kamatani Y, et al. Low-frequency coding variants in CETP and CFB are associated with susceptibility of exudative age-related macular degeneration in the japanese population. Hum Mol Genet. 2016 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Global Lipids Genetics Consortium. Willer CJ, Schmidt EM, et al. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1274–1283. doi: 10.1038/ng.2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ridker PM, Pare G, Parker AN, Zee RY, Miletich JP, Chasman DI. Polymorphism in the CETP gene region, HDL cholesterol, and risk of future myocardial infarction: Genomewide analysis among 18 245 initially healthy women from the women’s genome health study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:26–33. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.817304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Voight BF, Peloso GM, Orho-Melander M, et al. Plasma HDL cholesterol and risk of myocardial infarction: A mendelian randomisation study. Lancet. 2012;380:572–580. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60312-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johannsen TH, Frikke-Schmidt R, Schou J, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Genetic inhibition of CETP, ischemic vascular disease and mortality, and possible adverse effects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2041–2048. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 1986;232:34–47. doi: 10.1126/science.3513311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanigawa H, Billheimer JT, Tohyama J, Zhang Y, Rothblat G, Rader DJ. Expression of cholesteryl ester transfer protein in mice promotes macrophage reverse cholesterol transport. Circulation. 2007;116:1267–1273. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.704254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khera AV, Wolfe ML, Cannon CP, Qin J, Rader DJ. On-statin cholesteryl ester transfer protein mass and risk of recurrent coronary events (from the pravastatin or atorvastatin evaluation and infection therapy-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 22 [prove it-timi 22] study) Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:451–456. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tall AR, Yvan-Charvet L, Terasaka N, Pagler T, Wang N. HDL, ABC transporters, and cholesterol efflux: Implications for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2008;7:365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brousseau ME, Diffenderfer MR, Millar JS, Nartsupha C, Asztalos BF, Welty FK, Wolfe ML, Rudling M, Bjorkhem I, Angelin B, Mancuso JP, Digenio AG, Rader DJ, Schaefer EJ. Effects of cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibition on high-density lipoprotein subspecies, apolipoprotein A-I metabolism, and fecal sterol excretion. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1057–1064. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000161928.16334.dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.