Abstract

Background

Antihypertensive medication use may vary by race and ethnicity. Longitudinal antihypertensive medication use patterns are not well described in women.

Methods and Results

Participants from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a prospective cohort of women (n=3302, aged 42–52), who reported a diagnosis of hypertension or antihypertensive medication use at any annual visit were included. Antihypertensive medications were grouped by class and examined by race/ethnicity adjusting for potential confounders in logistic regression models. A total of 1707 (51.7%) women, mean age 50.6 years, reported hypertension or used antihypertensive medications at baseline or during follow‐up (mean 9.1 years). Compared with whites, blacks were almost 3 times as likely to receive a calcium channel blocker (odds ratio, 2.92; 95% CI, 2.24–3.82) and twice as likely to receive a thiazide diuretic (odds ratio, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.93–2.94). Blacks also had a higher probability of reporting use of ≥2 antihypertensive medications (odds ratio, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.55–2.45) compared with whites. Use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers and thiazide diuretics increased over time for all racial/ethnic groups. Contrary to our hypothesis, rates of β‐blocker usage did not decrease over time.

Conclusions

Among this large cohort of multiethnic midlife women, use of antihypertensive medications increased over time, with angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers becoming the most commonly used antihypertensive medication, even for blacks. Thiazide diuretic utilization increased over time for all race/ethnic groups as did use of calcium channel blockers among blacks; both patterns are in line with guideline recommendations for the management of hypertension.

Keywords: disparities, hypertension, medication, race/ethnicity, women

Subject Categories: Hypertension, Health Services, Race and Ethnicity, Women, Epidemiology

Introduction

An estimated 76 million adults have hypertension (HTN), which translates into 1 of 3 adults.1 After age 55, women have equal or greater prevalence of HTN compared with men.2 Life expectancy for women with HTN is on average 4.9 years shorter than women with normal blood pressure (BP) at the age of 50.3 The prevalence of HTN among black women in the United States is one of the highest in the world, at more than 40%.1 Furthermore, blacks develop HTN at younger ages than other racial/ethnic groups and are at higher risk for adverse outcomes including stroke and renal failure.4, 5

Effective management of HTN results in reduction of cardiovascular events including stroke and heart disease.6, 7, 8 In 2002, the Antihypertensive and Lipid Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT), a randomized, double‐blind, multicenter trial, compared 4 classes of antihypertensive medications; angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), represented by lisinopril; calcium channel blockers (CCBs), represented by amlodipine; α‐blockers, represented by doxazosin; and thiazide diuretics (THZDs), represented by chlorthalidone.8 The doxazosin arm was terminated early because of increased risk for stroke, combined cardiovascular disease (CVD), and heart failure (HF) compared with chlorthalidone.9 Among both blacks and non‐blacks, chlorthalidone, compared with lisinopril, was associated with significantly lower rates of HF, combined coronary heart disease, and combined CVD. In addition, for blacks, chlorthalidone was associated with significantly lower rates of stroke. Compared with amlodipine, chlorthalidone was associated with significantly lower risk for HF in both blacks and non‐blacks.8 The ALLHAT investigators recommended THZDs as first‐step therapy for HTN given equivalency between the treatment groups for the primary outcome and the superiority of chlorthalidone compared with amlodipine for HF, and compared with lisinopril for combined cardiovascular disease (CVD), stroke, and HF, as well as the lower expense of chlorthalidone compared with lisinopril and amlodipine.8

In the following year, the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) recommended the use of THZD diuretics as initial pharmacologic therapy for HTN management.10 More recently, the 2014 Evidence‐Based Guidelines for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults (Eighth Joint National Committee) recommended the initiation of THZDs, or ACEIs/ARBs or CCBs, alone or in combination for non‐black patients with HTN.11 For black patients with HTN, the writing committee recommended THZDs or CCBs, alone or in combination.

To date, little is known about patterns of antihypertensive medication utilization among midlife women, particularly variations by race/ethnicity. We sought to describe patterns of antihypertensive medication classes among women by race/ethnicity, over time using data from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a prospective cohort study of women transitioning through menopause. We hypothesized that THZDs would increase over time, with a greater increase around the time of ALLHAT and JNC 7 publication, and that both THZD and CCB use would increase among blacks while ACEI/ARB use would decline. We also hypothesized that use of β‐blockers (BBs) would decline for all women irrespective of race and ethnicity.

Methods

Study Population

SWAN is an ongoing community‐based longitudinal study with seven clinical sites. The overall aim of SWAN is to examine a wide variety of health‐related characteristics among women transitioning through menopause. The full study design and procedures, including recruitment and enrollment, have been described in detail elsewhere.12, 13 Between November 1995 and October 1997, 3302 women were enrolled from 7 geographically distinct sites across the United States. Sites used various sampling frameworks and recruitment strategies to enroll representative groups of women from the surrounding communities. All sites enrolled non‐Hispanic whites in addition to a specific minority racial/ethnic group. For the Boston, MA; Chicago, IL; Pittsburgh, PA; and Detroit, MI, sites, black women were enrolled, while Chinese and Hispanic and Japanese women were enrolled at the Oakland, CA; Hudson County, NJ; and Los Angeles, CA, sites, respectively. Eligibility requirements for SWAN included age between 42 and 52 years upon entry, menses within the 3 months prior to enrollment, and presence of their uterus and at least one ovary at time of enrollment. Of note, women who had their uterus and/or ovaries removed after enrollment were not excluded but were defined as unknown menopausal status. Women who reported taking oral contraceptives or hormonal therapy in the prior 3 months of a screening visit were also excluded from enrollment. Each participant read and signed an informed consent document, and all methods used in SWAN were approved by the institutional review boards at each study site.

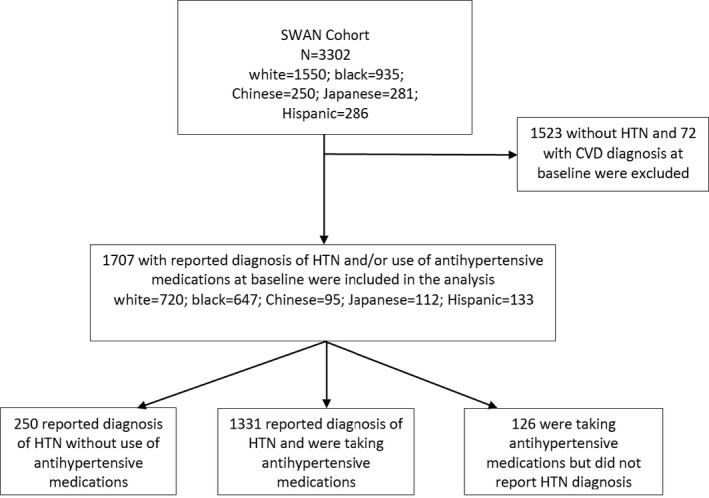

For our analysis, we included women who were classified as having HTN at any visit from the date of enrollment through visit 12 (January 1996–April 2013). A woman was considered to have HTN if she reported use of one or more medications to control BP and/or reported that her healthcare provider told her she had HTN. Women with a diagnosis of coronary artery disease or CVD at baseline were excluded (n=72) as they may use antihypertensive medications without a prior diagnosis of HTN. Of the 3302 women in SWAN, 1523 women without HTN and 72 with a diagnosis of CVD at baseline were excluded from this analysis. A total of 1707 participants who reported use of antihypertensives and/or reported that their provider told them they had HTN were included in the current analysis. Of these, 126 women were taking antihypertensive medications but did not report HTN, and 250 women reported HTN without taking antihypertensive medications (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram. CVD indicates cardiovascular disease; HTN, hypertension; SWAN, Study of Women's Health Across the Nation.

Use of Antihypertensive Medications

The primary aim of this study was to examine antihypertensive medication utilization patterns over time by medication class for each of the racial/ethnic groups enrolled in SWAN. Each participant was asked at each annual visit whether she has been told by a healthcare provider that she has high BP or a diagnosis of HTN since her last study visit. Participants also reported on the use of all medications in the past 30 days in the context of a detailed medication inventory and review by a trained study interviewer at each annual visit.

Antihypertensive drugs were grouped by class and included the following: ACEIs/ARBs, BBs, CCBs, THZDs, α‐blockers, loop diuretics, and potassium‐sparing diuretics. If a woman reported using ≥2 antihypertensives we counted these separately. For the multivariate models, use of ≥2 antihypertensives were categorized as combination. We examined prevalence of antihypertensive medication use over time. SWAN did not collect data on specific doses for the majority of visits; therefore, dose was not considered in this analysis.

Other Measures

Information on demographic characteristics was collected at the baseline SWAN visit and included age at entry, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic characteristics (highest education level attained, income, occupation), calendar year, and SWAN site. Information on medical history was assessed by self‐report at baseline and each subsequent annual visit, and included newly diagnosed CVD, diabetes mellitus, and renal disease. Participants were free of known CVD (prior myocardial infarction, stroke, revascularization, angina) at baseline; these outcomes were assessed at each annual visit. Income was included in models as a categorical variable (<20K, 20 to <50K, 50 to <100K, 100 to <150K, and 150K+). Information on a number of additional risk factors for HTN was collected at baseline and during follow‐up, including body mass index (kg/m2) and smoking status.

Menopausal status was defined as premenopausal, early perimenopausal, late perimenopausal, and postmenopausal according to predefined definitions.12, 13 Premenopausal status was defined as a menstrual period within the past 3 months with no change in regularity. Early perimenopause was defined as a menses within the past 3 months with a change in regularity. For these analyses, premenopausal and early perimenopausal were combined. Late perimenopause was defined as no menses for ≥3 months but at least one period within the past 12 months. Postmenopause was defined as no menses for ≥12 consecutive months with no other reason for the amenorrhea. Menopausal status was categorized as unknown if a woman had used hormonal therapy, had a hysterectomy, or had bilateral salpingo‐oophorectomy prior to becoming postmenopausal. Menopausal status was added to models as a time‐varying covariate. Race/ethnicity and menopausal status were examined separately as independent variables.

Statistical Analysis

We described the baseline participant characteristics in each ethnic group using descriptive statistics (mean, median, and range). Continuous variables were analyzed using ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis tests, whereas categorical variables were analyzed using chi‐square test. All variables assessed at baseline and each annual visit were included in the models as time‐varying covariates. After grouping the most common antihypertensive medications by class, we examined racial differences over time using generalized estimation equations, starting from SWAN baseline in 1996. The autoregressive covariance structure14 was used in each model. This structure has homogeneous variances and correlations that decline exponentially with distance.

Factors selected a priori for inclusion in the base models included several covariates known to be possible correlates of HTN: race/ethnicity (white, black, Chinese, Japanese, and Hispanic), age, body mass index, diabetes mellitus, and menopause transition stage. CVD events, which occurred during follow‐up, were also added to the models. Other covariates of interest included educational level, income, smoking status, and BP (systolic and diastolic as time‐varying covariates). Interaction terms for ethnicity and diabetes mellitus and ethnicity and CVD were also included in the models. Ethnicity included all race/ethnicity groups (white, black, Chinese, Japanese, and Hispanic) when used as an interaction term. We examined the data two ways, by calendar year and by time relative to the final menstrual period. We did not find any association of medication use around final menstrual period, thus we chose to present the data by calendar year in relation to publication of major clinical treatment guidelines and clinical trials. Subgroup analysis excluding the 126 women who reported use of antihypertensive medications but did not report HTN. We also examined use of antihypertensives by study site. Results are expressed as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs.

Since women with specific comorbidities may be prescribed a particular class of antihypertensive medication, we performed a subgroup analysis for women with diabetes mellitus. Because of the low prevalence of vascular disease in this cohort, medication class by stroke or transient ischemic attack was not examined. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

At enrollment, 46.7%, 28.3%, 8.5%, 7.8%, and 8.7% of the 3302 participants were white, black, Japanese, Chinese, and Hispanic, respectively. A total of 1707 women reported having been diagnosed with HTN and/or using antihypertensive medications between January 1996 and April 2012. Characteristics of these women at the visit where HTN was identified are shown in Table 1. Among women with HTN, 42.2%, 37.9%, 5.6%, 5.6%, and 7.8% were white, black, Chinese, Japanese and Hispanic, respectively. Mean follow‐up was 9.1 years (SD 5.8 years). The mean age when HTN was first reported was 50.6±5.5 (SD) years. The majority (73.1%) had completed some years of college or greater. Approximately 30% of SWAN participants with HTN were late perimenopausal or postmenopausal at the time of first reported diagnosis of HTN. Mean body mass index was 31.3 kg/m2, consistent with obesity. In terms of comorbidities, ≈15% of women reported current smoking, with the highest rates for black (21.0%) and the lowest rates for Chinese women (1.1%). Percentage of diabetes mellitus ranged from 4.5% in Japanese women to 13.3% in black women. Among these women, those reporting a diagnosis of heart disease or stroke during follow‐up were low.

Table 1.

Demographics of Study Participants at Time of First Reported HTN Diagnosis

| Characteristic, No. (%) | Total (N=1707) | White (n=720) | Black (n=647) | Chinese (n=95) | Japanese (n=112) | Hispanic (n=133) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 50.6 (5.5) | 50.8 (5.5) | 49.7 (5.1) | 52.4 (6.0) | 52.2 (5.8) | 50.1 (5.9) | 0.0001 |

| Education level | 0.0001 | ||||||

| High school or less | 440 (25.8) | 128 (17.8) | 181 (28.0) | 28 (29.5) | 19.0 (17.0) | 84 (63.2) | |

| Some college or greater | 1248 (73.1) | 586 (81.4) | 457 (70.6) | 67 (70.5) | 93 (83.0) | 45 (33.8) | |

| Menopausal status | 0.02 | ||||||

| Premenopause/early perimenopause | 1064 (62.8) | 434 (60.7) | 441 (68.5) | 47 (50.1) | 61 (54.4) | 81 (63.3) | |

| Late perimenopause | 89 (5.3) | 39 (5.5) | 30 (4.7) | 7 (7.5) | 6 (5.4) | 7 (5.5) | |

| Postmenopause | 421 (24.8) | 187 (26.1) | 129 (20.1) | 32 (34.0) | 35 (31.3) | 38 (29.7) | |

| Menopausal status unknowna | 120 (7.1) | 56 (7.8) | 44 (6.8) | 8 (8.5) | 10 (9.0) | 2 (1.6) | |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 31.3 (7.7) | 30.8 (7.5) | 33.8 (7.7) | 25.2 (4.9) | 24.6 (4.0) | 31.6 (6.5) | 0.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 127 (18) | 123 (15) | 133 (20) | 125 (15) | 121 (13) | 130 (13) | 0.0001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 79 (11) | 77 (6) | 81 (12) | 79 (11) | 79 (10) | 83 (9) | 0.0001 |

| Current smoking (yes or no) | 263 (15.4) | 97 (13.5) | 136 (21) | 1 (1.1) | 10 (8.9) | 19 (14.3) | 0.0001 |

| History of diabetes mellitus | 174 (10.2) | 60 (8.3) | 89 (13.3) | 6 (6.3) | 5 (4.5) | 16 (12.0) | 0.006 |

| History of CHD | 12 (0.7) | 3 (0.4) | 7 (1.1) | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.16 |

| History of stroke/TIA (yes or no) | 12 (0.7) | 7 (1.0) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) | 0.15 |

| Self‐reported diagnosis of HTN—not taking medication | 250 (14.6) | 124 (17.2) | 70 (10.8) | 12 (12.6) | 19 (17.0) | 25 (18.8) | 0.007 |

| Antihypertensive medication class | |||||||

| ACEI/ARB | 365 (21.4) | 151 (21.0) | 133 (26.6) | 12 (12.6) | 32 (38.6) | 37 (27.8) | 0.02 |

| β‐Blocker | 274 (16.1) | 119 (16.5) | 96 (14.8) | 20 (21.1) | 25 (22.3) | 14 (10.5) | 0.06 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 229 (13.4) | 70 (9.7) | 119 (18.4) | 5 (5.3) | 15 (13.4) | 20 (15.0) | 0.0001 |

| Thiazide diuretic | 381 (22.3) | 138 (19.2) | 197 (30.4) | 18 (18.9) | 15 (13.4) | 12 (9.0) | 0.0001 |

| Use of ≥2 antihypertensive medications | 220 (12.9) | 77 (10.7) | 107 (16.5) | 4 (4.2) | 18 (16.1) | 14 (10.5) | 0.0001 |

| Other antihypertensive medicationsb | 250 (14.7) | 99 (39.6) | 133 (53.2) | 4 (1.6) | 9 (3.6) | 5 (2.0) | 0.0001 |

ACEI indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CHD, coronary heart disease; HTN, hypertension; TIA, transient ischemia attack.

Menopausal status was categorized as unknown if a woman had used hormonal therapy or had a hysterectomy (with or without bilateral oophorectomy prior to their final menstrual period).

Other antihypertensive medications include α‐blockers, nonthiazide diuretics, clonidine, hydralazine, methyldopa, minoxidil, and reserpine.

A total of 250 women (14.6% of all women with HTN) in the SWAN cohort reported being diagnosed with HTN but not taking antihypertensive medications. Black and Chinese women were less likely to report a diagnosis of HTN without being on pharmacotherapy as compared with white, Japanese, or Hispanic women.

The most common classes of antihypertensive medications used by SWAN women were THZDs (22.3%) and ACEIs/ARBs (21.4%), followed by BBs (16.1%) and CCBs (13.4%) (Table 1). Japanese patients reported the highest rate (38.6%) of ACEI/ARB use, followed by Hispanics (27.8%) and blacks (26.6%). BB use was more common among Chinese (21.1%) and Japanese (22.3%) patients compared with the other racial/ethnic groups. Almost one third of blacks (30.4%) were taking a THZD compared with 19.2% of white and 18.9% of Chinese patients. The lowest rates of THZD use were observed among Hispanics (9.0%). The number of women who reported taking ≥2 antihypertensive medications was 12.9%. Blacks reported the highest rates of CCB use (18.4%), followed by Hispanics (15%). Less commonly, used antihypertensive medications (data not shown) included non‐THZD diuretics such as loop diuretics and potassium‐sparing diuretics (14.5%) and α‐blockers (0.5%).

We also examined the probability of taking a specific antihypertensive medication class, by race/ethnicity after adjusting for age, body mass index, menopausal status, systolic BP, diabetes mellitus, education, and income levels (Table 2). Among women with HTN, blacks were more likely than whites to report using CCBs (OR, 2.92; 95% CI, 2.24–3.82), THZDs (OR, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.93–2.94), and ≥2 antihypertensive medications (OR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.55–2.45). Use of ACEIs/ARBs and BBs were not statistically significantly different between blacks and whites. Hispanic women were more likely to report using ACEIs/ARBs (OR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.36–3.02) and CCBs (OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.13–2.89), compared with whites, while use of BBs, THZDs, and ≥2 antihypertensive medications were similar. Chinese patients reported similar use of all antihypertensive medications compared with whites, with the exception of CCBs, which were used less often (OR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.19–0.89). Among Chinese patients, THZDs were used more often as compared with whites (OR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.12–2.52). No differences in antihypertensive medication classes were observed between Japanese and white patients. We observed no significant differences after further adjusting for study site (data not shown). We also stratified by study site and found that patterns of use were similar between sites (data not shown). In sensitivity analyses, we observed no significant differences when women of unknown menopausal status were removed from the models.

Table 2.

Odds Ratio of Taking Antihypertensives by Medication Class and Racial/Ethnic Group

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CIs) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACEIs/ARBs | β‐Blockers | Calcium Channel Blockers | Thiazide Diuretics | Combination | |

| Black vs white | 1.13 (0.91–1.40) | 0.92 (0.72–1.19) | 2.92 (2.24–3.82), P<0.0001 | 2.38 (1.93–2.94), P<0.0001 | 1.95 (1.55–2.45), P<0.0001 |

| Hispanic vs white | 2.03 (1.36–3.02), P=0.005 | 0.80 (0.49–1.31) | 1.81 (1.13–2.89), P=0.01 | 0.66 (0.42–1.05) | 1.31 (0.86–2.00) |

| Chinese vs white | 0.79 (0.52–1.20) | 1.20 (0.76–1.90) | 0.47 (0.19–0.89), P=0.03 | 1.68 (1.12–2.52), P=0.01 | 0.83 (0.54–1.28) |

| Japanese vs white | 1.25 (0.85–1.86) | 1.22 (0.79–1.87) | 1.54 (0.97–2.45) | 0.98 (0.67–1.43) | 1.46 (0.96–2.23) |

Adjusted for age, body mass index, menopausal status, systolic blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, education, income, cardiovascular disease (CVD), ethnicity×CVD, and ethnicity×diabetes mellitus. Combination was defined as the reported use of ≥2 antihypertensive medications by a participant. ACEIs indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers.

Since women with diabetes mellitus may be more likely to be prescribed ACEIs/ARBs, we examined use of antihypertensive medications by race/ethnicity, comparing diabetics with nondiabetics (Table 3). Among white, black, and Japanese women, those with diabetes mellitus were more likely to use ACEIs/ARBs compared with nondiabetic women (OR, 1.70 [95% CI, 1.28–2.24] for whites, OR, 2.33 [95% CI, 1.84–2.95] for blacks, and OR 2.1 [95% CI 1.22–3.64] for Japanese women). Black women with diabetes mellitus were also more likely to be using ≥2 antihypertensive medications (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.12–2.0) and less likely to be taking a THZD (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.56–0.98) compared with black nondiabetic women. We also excluded women who reported use of antihypertensive medications but did not report having HTN and observed no significant differences, compared with the main analysis (Table 2), with the exception of greater CCB use among Japanese women (OR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.05–2.70) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Odds Ratio of Taking Antihypertensives by Medication Class and Racial/Ethnic Group Comparing Diabetics With Nondiabetics

| Diabetics vs Nondiabetics | Odds Ratio (95% CIs) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACEIs/ARBs | β‐Blockers | Calcium Channel Blockers | Thiazide Diuretics | Combination | |

| Total | 1.93 (1.47–2.53) | 0.90 (0.71–1.14) | 0.94 (0.66–1.35) | 1.11 (0.86–1.44) | 1.22 (0.93–1.60) |

| White | 1.70 (1.28–2.24), P=0.0002 | 0.93 (0.73–1.18) | 0.96 (0.66–1.40) | 1.00 (0.78–1.31) | 1.17 (0.88–1.54) |

| Black | 2.33 (1.84–2.95), P=0.0001 | 1.19 (0.92–1.52) | 1.02 (0.82–1.28) | 0.74 (0.56–0.98), P=0.03 | 1.53 (1.12–2.0), P=0.001 |

| Chinese | 2.11 (0.98–4.56) | 0.97 (0.54–1.70) | 1.37 (0.63–3.01) | 0.84 (0.62–1.12) | 1.43 (0.73–2.79) |

| Japanese | 2.10 (1.22–3.64), P=0.008 | 0.89 (0.63–1.26) | 0.54 (0.16–1.80) | 1.04 (0.34–3.20) | 0.78 (0.38–1.60) |

| Hispanic | 1.67 (0.85–3.27) | 0.63 (0.26–1.52) | 0.62 (0.27–1.40) | 0.68 (0.29–1.58) | 0.92 (0.44–1.92) |

Nondiabetics are the reference group, adjusted for age, body mass index, menopausal status, systolic blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, education, income, cardiovascular disease (CVD), ethnicity×CVD, and ethnicity×diabetes mellitus. Combination was defined as the reported use of ≥2 antihypertensive medications by a participant. ACEIs indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers.

Table 4.

Odds Ratio of Taking Antihypertensives by Medication Class and Racial/Ethnic Group*

| Odds Ratio (95% CIs) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACEIs/ARBs | β‐Blockers | Calcium Channel Blockers | Thiazide Diuretics | Combination | |

| Black vs white | 1.09 (0.87–1.35) | 0.99 (0.76–1.28) | 3.12 (2.37–4.12), P<0.0001 | 2.35 (1.89–2.92), P<0.0001 | 1.91 (1.51–2.40), P<0.0001 |

| Hispanic vs white | 1.86 (1.24–2.77), P=0.003 | 0.84 (0.51–1.38) | 1.90 (1.17–3.06), P=0.01 | 0.65 (0.41–1.04) | 1.24 (0.81–1.89) |

| Chinese vs white | 0.74 (0.48–1.13) | 1.13 (0.70–1.85) | 0.43 (0.20–0.96), P=0.04 | 1.70 (1.12–2.57), P=0.01 | 0.78 (0.51–1.21) |

| Japanese vs white | 1.18 (0.79–1.76) | 1.25 (0.79–1.96) | 1.69 (1.05–2.70), P=0.03 | 0.96 (0.66–1.41) | 1.42 (0.93–2.12) |

Adjusted for age, body mass index, menopausal status, systolic blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, education, income, cardiovascular disease (CVD), ethnicity×CVD, and ethnicity×diabetes mellitus. ACEIs indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers. Combination was defined as the reported use of ≥2 antihypertensive medications by a participant.

*Excluding women who reported antihypertensive medication use but not a diagnosis of hypertension.

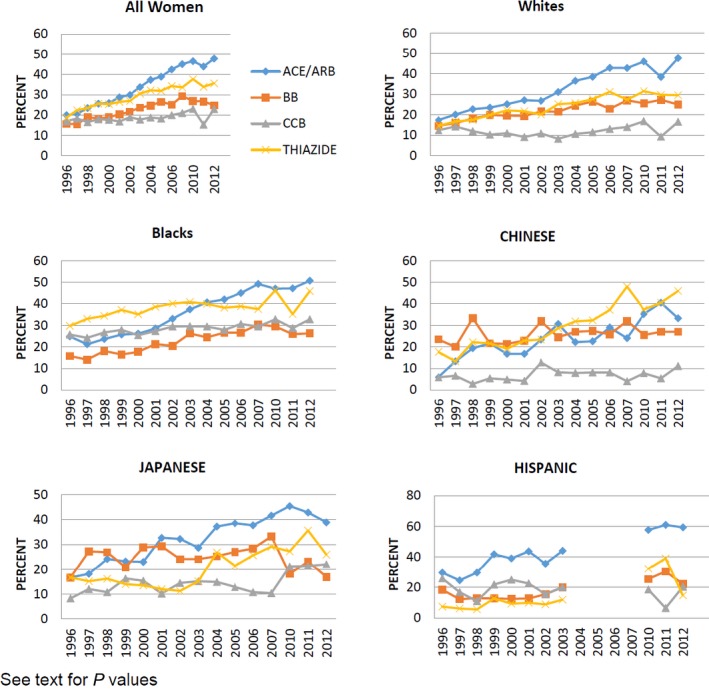

We next examined antihypertensive medication patterns of use over time (Figure 2). At the beginning of data collection in 1996, use of ACEIs/ARBs, BBs, CCBs, and THZDs were similar. By 2012, the most common antihypertensive medication class reported was ACEIs/ARBs followed by THZDs for white, black, and Japanese race/ethnic groups. The greatest increase over time was observed for ACEIs/ARBs (20.0–47.8%) followed by THZDs (18.8–35.7%). As the cohort aged, greater use of ≥2 antihypertensive medications were reported (P<0.0001). In Chinese patients, THZD use increased from 17.7% to 46% (P=0.01), and ACEI/ARB use increased from 5.9% to 33.3% (P=0.0008), while BB use remained essentially unchanged (23.5–27%) (P=0.52). By 2012, the most common antihypertensive medications reported by Chinese patients were THZDs followed by ACEIs/ARBs. BB use did not decline significantly over time among any of the groups, and increased among the following groups: whites (P=0.0001), blacks (P=0.0001), and Hispanics (P=0.03). Lastly, although use of THZDs increased over time, we did not observe a significant increased use around the time of ALLHAT or JNC 7 publication (2002–2003) or shortly thereafter (P=0.40).

Figure 2.

Antihypertensive medications over time by race/ethnicity. ACE indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BB, β‐blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; THIAZIDE, thiazide diuretic.

Discussion

In this large, multiethnic cohort of midlife women, we observed that use of antihypertensive medications increased over time as participants aged. During follow‐up, THZDs and ACEI/ARB utilization increased for most racial/ethnic groups; however, no clear uptake in THZDs was noted around the time of publication for ALLHAT or JNC 7. Furthermore, ACEIs/ARBs were more commonly reported compared with THZDs for most racial/ethnic groups by 2012 and BB use did not appear to decline over time as was expected. We also noted that the use of CCBs was higher in black women than other groups.

The number of SWAN women who reported antihypertensive medication use increased as participants aged. Ample evidence exists demonstrating increases in HTN with age10, 15; thus, an increase in antihypertensive medications was expected. Among participants in the Framingham Heart Study, the probability of receiving antihypertensive medications over a lifetime was 60%. Similar rates of antihypertensive use have been observed in data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES).16 These findings show comparable rates of antihypertensive medication reported by SWAN women.

We had expected to see a significant increase in THZD use during, or shortly after, the years in which ALLHAT and JNC 7 were published (2002–2003). THZDs have long been recommended for controlling BP, with reductions in CVD outcomes, and are low‐cost agents, which can promote adherence.11, 17, 18, 19 In 2003, the JNC 7 report recommended THZDs for the treatment of stage I HTN.10 Although we observed no specific point of increase in THZD use during those years, an increase in THZD and ACEI/ARB use was observed during the period examined. ACEI/ARB use increased among all groups over time, with the exception of Chinese women, who reported THZDs as the most commonly used antihypertensive medication class by 2012. Among the SWAN women, THZDs were the second most commonly used antihypertensive medication class after ACEIs/ARBs. Using data from NHANES, Gu et al16 observed diuretics to be the most commonly used antihypertensive medications as of 2009–2010, of which THZDs were the most common diuretic used. Of note, ACEIs were the second most commonly used antihypertensive drug class. When individual antihypertensive medications were examined, lisinopril was the most commonly reported antihypertensive medication used.16

In contrast, the National Disease and Therapeutic Index, which surveyed a national sample of US physicians between 1998 and 2004, noted ACEIs to be the leading antihypertensive prescribed,20 which is similar to the utilization patterns observed in the SWAN cohort. Data from the National Disease and Therapeutic Index did note an increase in THZD prescriptions after publication of ALLHAT in 2002, which we did not observe in the SWAN data.

We also expected to see a decline in the use of BBs for BP management, given the recommendation of JNC 7. Although there was no significant increase in BB use in general, there was an increase among whites and blacks. In contrast to our hypothesis, we did not observe a significant decline in use, with the exception among Japanese patients. Prior data from NHANES noted reductions in the use of BBs in the late 1990s through 2002.17 However, recent data from NHANES (2009–2010) observed an increase in BB use from 20.3% to 31.9%.16 HTN trials using BBs have not demonstrated a reduction in CVD events in comparison to other classes of antihypertensive medications.21, 22 In the ASCOT‐BPLA (Anglo‐Scandinavian Cardiac Outcome Trial‐Blood Pressure Lowering) trial, adults with HTN randomized to atenolol had higher rates of CVD events compared with those randomized to amlodipine.22 A meta‐analysis examined use of BBs for primary HTN and also noted no reduction in heart events with an increase in stroke.23 Consequently, current recommendations for management of HTN do not recommend BBs as first‐line agents.10, 11

In the SWAN cohort, black patients were almost 3 times as likely to report using a CCB compared with white patients. Investigators for the MESA (Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) trial observed that CCBs were the second most common antihypertensive medication class used by blacks, with ACEIs/ARBs being the most common.18, 24 Among black participants, ALLHAT investigators observed no significant difference between the CCB amlodipine and the THZD chlorthalidone for the primary outcome of nonfatal myocardial infarction or coronary heart disease mortality, or secondary outcomes including all‐cause mortality, stroke, combined coronary heart disease, or combined CVD.8 Higher rates of HF were observed among black participants randomized to amlodipine compared with those randomized to chlorthalidone.25, 26 In long‐term follow‐up of ALLHAT participants, investigators observed that black participants had an increased HF risk associated with amlodipine compared with chlorthalidone.27 However, it should be noted that participants were no longer blinded to treatments during the 8 to 10 years of post‐trial follow‐up and may have had their antihypertensive medication doses and class modified. Furthermore, use of ACEIs/ARBs are still the most commonly reported antihypertensive medication among blacks in SWAN. ALLHAT observed an increased risk for stroke, combined coronary heart disease, combined CVD, and HF in black participants randomized to lisinopril compared with those randomized to chlorthalidone.8 Given the ALLHAT results, and the recent 2014 guidelines, it is surprising to see no decline in the use of ACEIs/ARBs or CCBs among blacks.

Study Strengths and Limitations

Several strengths and limitations exist in the current study. First, data on dosage of medication was not collected for most years of the study. This limits our ability to examine the effective control of HTN among these women. Second, recruitment of minorities was completed at specific sites; therefore, differences observed in medication use patterns may reflect geographic patterns in use as opposed to differences by race/ethnicity. However, when we stratified by site, patterns in medication use appear similar by race, suggesting a lack of significant geographic variation. Last, data collection was interrupted for one site, which included enrollment of Hispanic women; thus, data between 2003 and 2010 are missing for Hispanics, which introduces potential for biases when examining longitudinal trends in antihypertensive classes for Hispanic women. We conducted a subgroup analysis with and without these women in our models to examine potential implications of this missing data and did not observe differences in our results.

Conclusions

Among this large cohort of multiethnic midlife women, use of antihypertensive medications increased over time, with ACEIs/ARBs becoming the most commonly used antihypertensive medication, even for blacks. THZD use increased over time for all race/ethnic groups as did CCB use among blacks. Both patterns are in line with guideline recommendations for the management of HTN.

Sources of Funding

The SWAN trial has grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Health and Human Services, through the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), and the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH) (grants U01NR004061, U01AG012505, U01AG012535, U01AG012531, U01AG012539, U01AG012546, U01AG012553, U01AG012554, and U01AG012495). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA, NINR, ORWH, or the NIH.

Disclosures

Derby reports research funding from the NIH. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Acknowledgments

Clinical Centers: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor—Siobán Harlow, PI 2011–present; MaryFran Sowers, PI 1994–2011; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA—Joel Finkelstein, PI 1999–present; Robert Neer, PI 1994–1999; Rush University, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL—Howard Kravitz, PI 2009–present; Lynda Powell, PI 1994–2009; University of California, Davis/Kaiser—Ellen Gold, PI; University of California, Los Angeles—Gail Greendale, PI; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY—Carol Derby, PI 2011–present, Rachel Wildman, PI 2010–2011; Nanette Santoro, PI 2004–2010; University of Medicine and Dentistry—New Jersey Medical School, Newark—Gerson Weiss, PI 1994–2004; and the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA—Karen Matthews, PI. National Institutes of Health Program Office: National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD—Winifred Rossi 2012–present; Sherry Sherman 1994–2012; Marcia Ory 1994–2001; National Institute of Nursing Research, Bethesda, MD—Program Officers. Central Laboratory: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor—Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services). Coordinating Center: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA—Maria Mori Brooks, PI 2012–present; Kim Sutton‐Tyrrell, PI 2001–2012; New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA—Sonja McKinlay, PI 1995–2001. Steering Committee: Susan Johnson, Current Chair; Chris Gallagher, Former Chair. We thank the study staff at each site and all the women who participated in SWAN.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e004758. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004758.)

References

- 1. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER III, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB; American Heart Association Statistics C and Stroke Statistics S . Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–e360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd‐Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Soliman EZ, Sorlie PD, Sotoodehnia N, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Franco OH, Peeters A, Bonneux L, de Laet C. Blood pressure in adulthood and life expectancy with cardiovascular disease in men and women: life course analysis. Hypertension. 2005;46:280–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferdinand KC, Ferdinand DP. Race‐based therapy for hypertension: possible benefits and potential pitfalls. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2008;6:1357–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hertz RP, Unger AN, Cornell JA, Saunders E. Racial disparities in hypertension prevalence, awareness, and management. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2098–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). SHEP Cooperative Research Group. JAMA. 1991;265:3255–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, Celis H, Arabidze GG, Birkenhager WH, Bulpitt CJ, de Leeuw PW, Dollery CT, Fletcher AE, Forette F, Leonetti G, Nachev C, O'Brien ET, Rosenfeld J, Rodicio JL, Tuomilehto J, Zanchetti A. Randomised double‐blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension. The Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst‐Eur) Trial Investigators. Lancet. 1997;350:757–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Major outcomes in high‐risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288:2981–2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Major cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients randomized to doxazosin vs chlorthalidone: the antihypertensive and lipid‐lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT). ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. JAMA. 2000;283:1967–1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr, Roccella EJ. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison‐Himmelfarb C, Handler J, Lackland DT, LeFevre ML, MacKenzie TD, Ogedegbe O, Smith SC Jr, Svetkey LP, Taler SJ, Townsend RR, Wright JT Jr, Narva AS, Ortiz E. 2014 evidence‐based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sowers M, Crawford SL, Sternfeld B, Morganstein D, Gold E, Greendale G, Evans D, Neer R, Matthews K, Sherman S, Lo A, Weiss G, Kelsey J. SWAN: a multi‐center, multi‐ethnic, community‐based cohort study of women and the menopausal transition In: Kelsey J, Lobo RA, Marcus R, eds. Menopause: Biology and Pathobiology. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000:175–188. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnston JM, Colvin A, Johnson BD, Santoro N, Harlow SD, Bairey Merz CN, Sutton‐Tyrrell K. Comparison of SWAN and WISE menopausal status classification algorithms. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2006;15:1184–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Patetta M. SAS, Longitudinal Data Analysis With Discrete and Continuous Responses. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ong KL, Cheung BM, Man YB, Lau CP, Lam KS. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among United States adults 1999–2004. Hypertension. 2007;49:69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gu Q, Burt VL, Dillon CF, Yoon S. Trends in antihypertensive medication use and blood pressure control among United States adults with hypertension: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001 to 2010. Circulation. 2012;126:2105–2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gu Q, Paulose‐Ram R, Dillon C, Burt V. Antihypertensive medication use among US adults with hypertension. Circulation. 2006;113:213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wright JT Jr, Probstfield JL, Cushman WC, Pressel SL, Cutler JA, Davis BR, Einhorn PT, Rahman M, Whelton PK, Ford CE, Haywood LJ, Margolis KL, Oparil S, Black HR, Alderman MH; ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group . ALLHAT findings revisited in the context of subsequent analyses, other trials, and meta‐analyses. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:832–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Psaty BM, Lumley T, Furberg CD. Meta‐analysis of health outcomes of chlorthalidone‐based vs nonchlorthalidone‐based low‐dose diuretic therapies. JAMA. 2004;292:43–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stafford RS, Monti V, Furberg CD, Ma J. Long‐term and short‐term changes in antihypertensive prescribing by office‐based physicians in the United States. Hypertension. 2006;48:213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dahlof B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Beevers G, de Faire U, Fyhrquist F, Ibsen H, Kristiansson K, Lederballe‐Pedersen O, Lindholm LH, Nieminen MS, Omvik P, Oparil S, Wedel H; LIFE Study Group . Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet. 2002;359:995–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dahlof B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, Wedel H, Beevers DG, Caulfield M, Collins R, Kjeldsen SE, Kristinsson A, McInnes GT, Mehlsen J, Nieminen M, O'Brien E, Ostergren J; ASCOT investigators . Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo‐Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial‐Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT‐BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:895–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lindholm LH, Carlberg B, Samuelsson O. Should beta blockers remain first choice in the treatment of primary hypertension? A meta‐analysis Lancet. 2005;366:1545–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kramer H, Han C, Post W, Goff D, Diez‐Roux A, Cooper R, Jinagouda S, Shea S. Racial/ethnic differences in hypertension and hypertension treatment and control in the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:963–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wright JT Jr, Dunn JK, Cutler JA, Davis BR, Cushman WC, Ford CE, Haywood LJ, Leenen FH, Margolis KL, Papademetriou V, Probstfield JL, Whelton PK, Habib GB; ALLHAT Cooperative Research Group . Outcomes in hypertensive black and nonblack patients treated with chlorthalidone, amlodipine, and lisinopril. JAMA. 2005;293:1595–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Einhorn PT, Davis BR, Wright JT Jr, Rahman M, Whelton PK, Pressel SL; ALLHAT Cooperative Research Group . ALLHAT: still providing correct answers after 7 years. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2010;25:355–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cushman WC, Davis BR, Pressel SL, Cutler JA, Einhorn PT, Ford CE, Oparil S, Probstfield JL, Whelton PK, Wright JT Jr, Alderman MH, Basile JN, Black HR, Grimm RH Jr, Hamilton BP, Haywood LJ, Ong ST, Piller LB, Simpson LM, Stanford C, Weiss RJ; ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group . Mortality and morbidity during and after the Antihypertensive and Lipid‐Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2012;14:20–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]