Abstract

Background

Noninvasive echocardiographic tissue Doppler assessment (E/e′) in response to exercise or pharmacological intervention has been proposed as a useful parameter to assess left ventricular (LV) filling pressure (LVFP) and LV diastolic dysfunction. However, the evidence for it is not well summarized.

Methods and Results

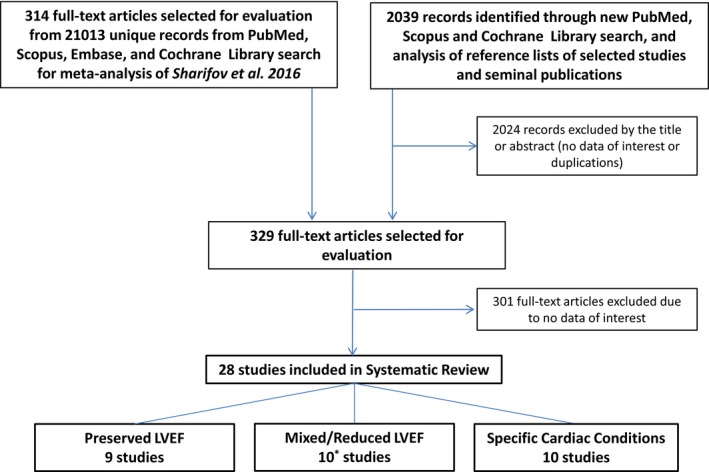

Clinical studies that evaluated invasive LVFP changes in response to exercise/other interventions and echocardiographic E/e′ were identified from PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases. We grouped and evaluated studies that included patients with preserved LV ejection fraction (LVEF), patients with mixed/reduced LVEF, and patients with specific cardiac conditions. Overall, we found 28 studies with 9 studies for preserved LVEF, which was our primary interest. Studies had differing methodologies with limited data sets, which precluded quantitative meta‐analysis. We therefore descriptively summarized our findings. Only 2 small studies (N=12 and 10) directly or indirectly support use of E/e′ for assessing LVFP changes in preserved LVEF. In 7 other studies (cumulative N=429) of preserved LVEF, E/e′ was not useful for assessing LVFP changes. For mixed/reduced LVEF groups or specific cardiac conditions, results similar to preserved LVEF were found.

Conclusions

We find that there is insufficient evidence that E/e′ can reliably assess LVFP changes in response to exercise or other interventions. We suggest that well‐designed prospective studies should be conducted for further evaluation.

Keywords: diastolic dysfunction echocardiography, diastolic heart failure, Doppler echocardiography, E/e′, exercise echocardiography, left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, left ventricular diastolic function, left ventricular filling pressure

Subject Categories: Echocardiography, Heart Failure, Diagnostic Testing, Exercise Testing, Clinical Studies

Introduction

Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction leading to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is a major clinical problem.1, 2, 3 Elevated left ventricular filling pressure (LVFP) is often used as a clinical surrogate for impaired diastolic function in patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).4, 5 LVFP is usually measured at rest in routine clinical practice. However, changes in LVFP with exercise or other physiological intervention provide incremental information to assess diastolic function.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 A direct measurement of LVFP requires an invasive intervention, which has significant risk and costs, and is therefore performed in select patients only. Echocardiography is frequently used for noninvasive evaluation of diastolic function and estimating LVFP.4, 5, 6 Echocardiographic quantification of LVFP is based on E/e′ measurement, which is the ratio of the early diastolic velocity on transmitral Doppler (E) and the early diastolic velocity of mitral valve annulus obtained from tissue Doppler (e′).4, 5, 6, 11, 12, 13, 14 The guidelines recommend using E/e′ in evaluating LV diastolic function.4, 5, 6, 10 In research studies, E/e′ is also used as a primary or secondary end point for assessing the treatment efficacy and quantifying changes in LVFP.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19

Despite extensive use of E/e′, there continues to be ongoing debate about the usefulness of E/e′ in assessing LVFP.20, 21, 22, 23, 24 In our recent comprehensive meta‐analysis, we have found limited evidence for the use of E/e′ under resting conditions to estimate LVFP in preserved LVEF.20 It has been suggested that changes in E/e′ with exercise or other physiological/pharmacologic interventions may more accurately reflect changes in the LVFP and diastolic properties.5, 6, 8, 10, 25 Here we decided to evaluate the evidence describing the relationship of E/e′ and LVFP in preserved LVEF with exercise or other physiological interventions. We also summarize the available evidence describing the relationship of E/e′ and LVFP in a wider spectrum of LVEF and for specific cardiac conditions.

Methods

Search Strategy and Study Selection

Original clinical studies that evaluated LVFP by using echocardiographic E/e′ and invasive techniques were screened from PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases to September 2016 using a number of search strategies (Figure). Specific search terms and full‐text studies excluded after evaluation are listed in Tables S1 and S2. Clinical studies (in English) that reported changes in E/e′ and invasively measured LVFP attributable to physiologic and/or pharmacologic or other therapeutic intervention and/or repeated serial measurements in the adult subjects (age >18 years) with any LVEF and clinical conditions were included. References of important studies were also reviewed for comprehensive search. LVFP measurements included LV end diastolic pressure, LV pre‐A wave pressure, LV mean diastolic pressure, left atrial pressure, and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) obtained during the left or right heart catheterization or from a permanently implantable cardiac pressure monitoring system. Only studies that utilized transthoracic echocardiographic pulsed‐wave tissue Doppler imaging for E/e′ measurements at interventricular septum (E/e′septal), lateral mitral annulus (E/e′lateral), and/or mean of septal and lateral values (E/e′mean) were selected.

Figure 1.

Summary of the literature search. Studies that include data for patients with preserved LVEF (LVEF ≥50%) were our primary interest. Other studies that include data for patients with mixed or reduced LVEF (LVEF <50%) and patients with specific cardiac conditions were our secondary interest. For this review, with studies identified during a comprehensive literature search for recent meta‐analysis, Sharifov et al20 were initially evaluated. An updated literature search was then performed based on specific search strings as described. One study included a data set for primary and secondary analysis. LVEF indicates left ventricular ejection fraction.

The studies were included if they reported at least 1 of the following data sets: (1) E/e′ and LVFP values at baseline and after intervention; (2) changes in E/e′ and LVFP values because of intervention; (3) assessment of correlation between E/e′ and LVFP postintervention, alone, or combined with baseline; (4) assessment of correlation between changes in E/e′ and LVFP with intervention; and (5) the diagnostic accuracy of either postintervention E/e′ values or postintervention changes in E/e′ to predict elevated LVFP or LVFP changes.

Patient Cohorts and Study Analysis

Included studies were grouped and analyzed based on patient cohorts. The first group was for studies that included patients with LVEF ≥50%, including HFpEF patients, but without a substantial number of moderate‐to‐severe valvular heart disease, hypertrophic or restrictive cardiomyopathy, congenital heart disease, acute coronary syndromes, septic shock, cardiac transplant, and atrial fibrillation. This group was our primary interest. Other groups were for studies that included patients with reduced/mixed LVEF, and for studies that included patients grouped with specific cardiac conditions (eg, cardiac transplants). Overall, we found 28 studies: 9 studies24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 for our primary interest, and 19 studies25, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51 for secondary interest (Figure). One study included a data set for primary and secondary interest.30 Since most of the studies were single center with differing methodologies with many reporting only a limited data set, we chose descriptive methodologies to summarize the results.

Results

Studies in LVEF ≥50% With or Without HFpEF

Table 1 summarizes study details and results for the 9 studies that included participants with preserved LVEF (≥50%), including HFpEF patients (see Table S3 for more details). All studies, except 1,29 had a prospective design and all studies, except 1,32 simultaneously measured echocardiographic and hemodynamic variables. Most of these studies had a low sample size (median N = 22 with interquartile range of 11–82). Three of these studies had subjects perform exercise stress echocardiography using a supine bicycle29, 31 or passive and then active leg‐raise33 for evaluating patients with suspected HFpEF. There was an increase in invasive LVFP but no consistent relationship for the changes in E/e′ postintervention in these 3 studies. Talreja et al31 found that E/e′ provides a reliable estimation of PCWP with exercise in a small study of 12 patients. Based on their scatterplot,31 we estimated that stress E/e′septal >15 predicts PCWP ≥20 mm Hg with sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 100%. Maeder et al29 found decreased E/e′septal with exercise and no correlation between poststress E/e′septal and PCWP. In the largest exercise study in patients with exertional dyspnea (N=181), Choi et al33 recorded no change of E/e′septal despite a significant elevation of LV end diastolic pressure with passive and active leg raise.

Table 1.

Summary of Studies With Subjects With Preserved LVEF (>50%), With or Without HFpEF Patients

| Study | Study Design | Population | N | Intervention | Echo./Cath. Timing | LVFP Change Postintervention | E/e′ Change Postintervention | E/e′‐LVFP Relation Postintervention | ΔE/e′‐ΔLVFP Relation | Prediction of Elevated LVFP Postintervention | Study Summary for Relationship Between E/e′ and LVFP | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventions to increase LVFP | ||||||||||||

| Firstenberg, 200028 | Prospectivea | Healthy volunteers | 7 | Saline infusion | Simultaneous |

↑ PCWP |

↔ Lateral, Septal |

··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | E/e′ does not change despite LVFP increase |

| Talreja, 200731 | Prospective | Exertional dyspnea (NYHA class II–III) | 12 | Supine bicycle | Simultaneous |

↑ PCWP |

↑ Septal |

··· | ··· | Se./Sp.b: 83%/100% to predict PCWP ≥20 mm Hg if E/e′>15 | E/e′ does provide a reliable estimation of PCWP with exercise (E/e′ >15 is associated with PCWP >20 mm Hg) | |

| Maeder, 201029 | Case–Controla | 14 HFpEF and 8 matching Controls | 22 | Supine bicycle | Simultaneous |

↑ PCWP |

↓ Septal |

n.s. | ··· | ··· | E/e′ does not reflect the hemodynamic changes during exercise in HFpEF patients and in controls | |

| Choi, 201633 | Prospective | HFpEF (at rest 8<E/e′<15, E/A<1, or e′<8 cm/s) | 181 | Passive and active leg‐raise | Simultaneous |

↑ LVEDP, Pre‐A |

↔ Septal |

··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | E/e′ does not change despite LVFP increase |

| Interventions to decrease LVFP | ||||||||||||

| Firstenberg, 200028 | Prospectivea | Healthy volunteers | 7 | Lower‐body negative pressure | Simultaneous |

↓ PCWP |

↔ Lateral, Septal |

··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | E/e′ does not change despite LVFP decrease |

| Efstratiadis, 200932 | Prospective | HFpEF patients | 10 | Nesiritide i.v. | Consequentive |

↓ LVEDP, PCWP |

↓ Lateral |

··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | See also Weeks, 200845 |

| Chan, 201127 | Prospective | Patients without significant CAD | 16 | Dobutamine i.v. | Simultaneous |

↓ LVEDP, LVMDP |

↔ Lateral, Septal |

n.s. | ··· | ··· | E/e′ does not predict changes in LVFP at peak stress with dobutamine | |

| Manouras, 201330 |

Prospectivea

Consecutive |

Stable angina and/or exertional dyspnea | 38 | Nitroglycerin i.v. | Simultaneous |

↓ LVEDP, Pre‐A |

↔ Lateral, Septal, Mean |

n.s. | n.s. | ··· | E/e′ does not reliably predict changes in LVFP; not recommended for monitoring load reducing therapy | Results for cohort with LVEF >55% |

| Santos, 201524 | Prospective | Unexplained dyspnea | 118 | Position change from supine to upright | Simultaneous |

↓ PCWP |

↔ Lateral, Septal, Mean |

n.s. | n.s. | ··· | E/e′ does not accurately estimate PCWP. Positional change in E/e′ does not reflect change in PCWP | |

| Analysis of combined measurements from baseline and during intervention | ||||||||||||

| Firstenberg, 200028 | Prospectivea | Healthy volunteers | 7 | Lower‐body negative pressure—saline infusion | Simultaneous |

↓↔↑ PCWP |

↔ Lateral, Septal |

n.s. | ··· | ··· | ··· | E/e′ does not change despite wide range of LVFP change |

| Bhella, 201126 | Prospective | 11 outpatient HFpEF, 24 old and 12 young healthy Controls | 47 | Lower‐body negative pressure—saline infusion | Simultaneous |

↓↔↑ PCWP |

··· Mean |

··· | ··· | ··· | E/e′ does not reliably track changes in LVFP; not recommended in research with healthy volunteers or for the titration of therapy in HFpEF patients | R 2 and Slopes for individual linear regression widely differed |

↑ or ↓ indicates statistically significant increase or decrease was measured in the cohort; ↔, no statistically significant change was measured in the cohort; CAD, coronary artery disease; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; Lateral, Septal, and Mean, E/e′lateral, E/e′septal, and E/e′mean; LVEDP, left ventricular end diastolic pressure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVFP, left ventricular filling pressure; LVMDP, left ventricular mean diastolic pressure; N, number of patients with LVEF >50% (not always a total N of patients in the study); n.s., study reports that correlation coefficient is not statistically significant; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; pre‐A, left ventricular pre‐A wave pressure; Se./Sp., Sensitivity and Specificity.

Based on our read.

Our assessment made from the study data.

In another set of studies, authors performed stress echocardiography using differing pharmacological interventions27, 30, 32 or body position change24 that resulted in significant decrease of LVFP (Table 1). Only in 1 small study,32 authors reported the decrease of group average E/e′lateral in response to decreased LVFP for 10 HFpEF patients. However, this study did not provide any individual data for further analysis. Interestingly, in another publication from the same group45 (Table 2), authors reported no correlation between individual changes of E/e′ and LVFP for a combined cohort of 10 HFpEF and 15 heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) patients. In studies24, 27, 30 with a total of 179 HFpEF and/or coronary artery disease patients, there were no significant changes in E/e′ values despite reduced LVFP. Furthermore, in these studies there was no significant correlation between postintervention values of E/e′ and LVFP or between individual changes in E/e′ and LVFP.

Table 2.

Summary of Studies With Subjects With Reduced or Various LVEF, With or Without HF

| Study | Study Design | Population | N | Intervention | Echo./Cath. Timing | LVFP change Postintervention | E/e′ Change Postintervention | E/e′‐LVFP Relation Postintervention | ΔE/e′‐ΔLVFP Relation | Prediction of Elevated LVFP Postintervention | Study Summary for Relationship Between E/e′ and LVFP | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventions to increase LVFP | ||||||||||||

|

Burgess, 200625

Gibby, 201344 |

Prospectivea | Unselected patients undergoing heart catheterization, LVEF 56±12% | 37 | Single‐leg supine cycle | Simultaneous |

↔(?)b

LVMDP |

↔(?)b

Septal |

Sign. | ··· |

To detect LVMDP >15 mm Hg: AUC: 0.89c; Se./Sp.: 73%/96% if E/e′ >13 in25 Se/Sp.: 67%/95% if E/e′ >13 in44 |

E/e′ does correlate with LVFP during exercise and it can be used to reliably identify patients with elevated LVFP during exercise | LVMDP and E/e′ significantly increased in 9 patients during exercise |

| Yamada, 201446 | Consecutive | Various chronic cardiac diseases, LVEF 58±14% | 22 | Leg‐positive pressure | Simultaneous |

↑ LVEDP. Pre‐A |

↑ Lateral |

··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | On group average, E/e′ does increase reflecting elevation of LVFP |

| Marchandise, 201440 | Prospective Consecutive | LV systolic dysfunction, LVEF 27±11% | 40 | Semisupine bicycle | Simultaneous |

↑ PCWP |

↓ Lateral, Septal, Mean |

Sign. | ··· | ··· | E/e′ is less reliable for estimating LVFP during exercise than at rest | |

| Interventions to decrease LVFP | ||||||||||||

| Weeks, 200845 | Prospective | 10 HFpEF and 15 HFrEF, LVEF 45±10% | 25 | Nesiritide i.v. | Consequentive |

↓ LVEDP, PCWP |

↓ Lateral |

··· | n.s. | ··· | E/e′ does not reflect changes in LVFP | See also Efstratiadis, 200932 |

| Manouras, 201330 |

Prospectivea

Consecutive |

Stable angina and/or exertional dyspnea, LVEF >40% | 65 | Nitroglycerin i.v. | Simultaneous |

↓ LVEDP, Pre‐A |

↔ Lateral, Septal, Mean |

n.s. | n.s. |

To detect LVEDP >16 mm Hg: AUC n.s. To detect Pre‐A >12 mm Hg: AUC n.s. |

E/e′ does not reliably predict changes in LVFP | |

| Egstrup, 201336 | Prospectivea | Chronic HFrEF, LVEF 36±8% | 14 | Dobutamine i.v. | Simultaneous |

↔ PCWP |

↔ Septal |

n.s. | ··· | ··· | E/e′ does not reflect the PCWP during low‐dose dobutamine | |

| Chiang, 201442 | Prospectivea Consecutive | Suspected CAD, LVEF 43±16% | 60 | Glyceryl trinitrate i.v. | Simultaneous |

↓ LVEDP, Pre‐A |

↓ Septal |

n.s. | ··· | ··· | E/e′ does not reflect changes in LVFP | |

| Serial or repeated measurements | ||||||||||||

| Ritzema, 201141 | Sub analysis of prospectively enrolled clinical trial cohort | Ambulant chronic HFrEF, LVEF 32±12% | 15 | 1 to 7 measurements (median 4) for 0 to 52 weeks (median 23 weeks) using implantable LAP monitoring system | Simultaneous |

↓↑ LAP |

↓↑ Lateral, Septal, Mean |

For total of 60 measurements Lateral: n.s. Septal: Sign. Mean: n.s. |

Septal: Sign. |

For total of 60 measurement: to detect LAP ≥15 mm Hg: Lateral AUC 0.90c; Se./Sp.: 73%/87% if E/e′≥12 Septal AUC 0.90c; Se./Sp.: 84%/91% if E/e′≥15 Mean AUC 0.95c; Se./Sp.: 84%/96% if E/e′≥14 |

While E/e′ weakly correlate with LAP, E/e′ does reliably detect raised LAP | |

| Goebel, 201150 | Sub analysis of prospectively enrolled clinical trial cohort | Patients scheduled for aortocoronary bypass surgery, LVEF between 25% and 35% | 5 | Repeated measurements for 6 months using a telemetric intraventricular pressure sensor | Simultaneous |

↓↑ LVEDP, LVMDP |

↓↑ Lateral, Septal, Mean |

For total of 21 measurements Lateral: n.s. Septal: n.s. Mean: n.s. |

··· |

For total of 21 measurements: to detect LVEDP >15 mm Hg: AUC n.s. to detect LVMDP >12 mm Hg: Lateral, Septal AUC n.s.; Mean AUC 0.82c |

E/e′ does not reliably correlate with LVFP, does not reliably detect raised LVFP | |

? indicates not clear from text; ↑ or ↓, statistically significant increase or decrease was measured in the cohort; ↔, no statistically significant change was measured in the cohort; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CAD, coronary artery disease; HFpEF/HFrEF, heart failure with preserved/reduced ejection fraction; LAP, left atrial pressure; Lateral, Septal, and Mean, E/e′lateral, E/e′septal, and E/e′mean; LVEDP, left ventricular end diastolic pressure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVFP, left ventricular filling pressure; LVMDP, left ventricular mean diastolic pressure; N, number of patients; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; pre‐A, left ventricular pre‐A wave pressure; Se./Sp., sensitivity and specificity; Sign./n.s., study reports that correlation coefficient is/is not statistically significant.

Based on our read.

Our assessment made from the study data.

Statistically significant value of AUC.

In 2 other studies, participants underwent preload changes leading to lower LVFP caused by low body negative pressure and increase in LVFP by saline infusion.26, 28 Both studies found that E/e′ cannot reliably track changes in LVFP in healthy people26, 28 and in HFpEF patients.26

Studies in Reduced or Mixed LVEF

Table 2 summarizes study details and results for the 10 studies that included participants with mixed or reduced LVEF (see Table S4 for more details). In the study of Burgess et al,25 which included 37 unselected patients with varying LVEF, authors reported a significant correlation (r=0.59) between E/e′septal and LV mean diastolic pressure during single‐leg supine exercise. They reported high AUC value (0.89) for exercise E/e′septal to predict an elevation of LV mean diastolic pressure >15 mm Hg.25 In their reports for the same patient cohort, E/e′septal >13 had sensitivity of ≈70% and specificity of ≈95% for estimating elevated LV mean diastolic pressure >15 mm Hg.25, 44 In another study of 22 patients,46 mean E/e′lateral increased with preload stress. However, on detailed analysis, E/e′lateral increase was observed in only a small subset of patients (N=6). No correlation of E/e′ and LVFP or diagnostic value of E/e′lateral was reported.46 In another study in patients with reduced LVEF (N=40), authors reported a significant correlation between exercise E/e′ and LVFP and a paradoxical decrease of exercise E/e′ values despite LVFP elevation.40

In 4 studies, investigators used different pharmacological agents to decrease LVFP and measured corresponding changes in E/e′ (Table 2).30, 36, 42, 45 Despite differences in patient cohorts, agents, and measured indices, all studies concluded that E/e′ does not reflect changes in LVFP.30, 36, 42, 45

In 2 studies, the investigators performed serial measurements using implanted hemodynamic measurement devices (Table 2).41, 50 In 1 study of 15 patients with chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, the investigators found high diagnostic values of E/e′mean, E/e′lateral, or E/e′septal to predict the elevated mean left atrial pressure (≥15 mm Hg). In their study, E/e′lateral and E/e′mean had no correlation and E/e′septal had only modest correlation (r=0.46) with mean left atrial pressure on serial measurements.41 In another study of 5 patients with reduced LVEF, the investigators found no correlation between E/e′ and LVFP and no significant diagnostic value of E/e′ to detect elevated LVFP on serial measurements.50

Studies in Specific Cardiac Conditions

Table 3 summarizes study details and results for the 10 studies that included participants with specific cardiac conditions (see Table S5 for more details). In 3 studies, cardiac transplant patients were evaluated.37, 38, 39 In 1 study of 14 transplant patients, serial measurements revealed an excellent correlation between changes in E/e′mean and changes in PCWP.39 In contrast, in another study with a larger cohort (N=57), there was no difference in the E/e′ values postexercise despite changes in PCWP.37 In another study with similarly large sample cohort, the investigators found low predictive power of exercise E/e′ for identifying elevated PCWP and a modest correlation for the E/e′‐PCWP and ΔE/e′‐ΔPCWP.38

Table 3.

Summary of Studies With Specific Cardiac Conditions

| Study | Study Design | Population | N | Intervention | Echo./Cath. Timing | LVFP Change Postintervention | E/e′ Change Postintervention | E/e′‐LVFP Relation Postintervention | ΔE/e′‐ΔLVFP Relation | Prediction of Elevated LVFP Postintervention | Study Summary for Relationship Between E/e′ and LVFP | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventions to increase LVFP | ||||||||||||

| Gurudevan, 200747 |

Retrospectivea

Consecutive |

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension with E<A (NYHA class III–IV), LVEF 66±9% | 61 | Pulmonary thromboendarterectomy | ≤48 hours before and ≤10±6 days after surgery |

↑ PCWP |

↑ Lateral, Septal |

··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | On group average, E/e′ does increase reflecting the postsurgery elevation of PCWP |

| Dalsgaard, 200949 | Prospectivea | Severe aortic stenosis, LVEF 57±8% | 28 | Supine bicycle | Simultaneous |

↑ PCWP |

↔ Lateral, Septal |

Sign. | n.s. | ··· | E/e′ does not detect exercise‐induced changes in PCWP in patients with severe aortic stenosis | |

| Meluzin, 201338 | Prospectivea | Heart transplants, LVEF 65±1% | 61 | Supine bicycle | Simultaneous |

? PCWP |

? Mean |

Sign. | Sign. | Only for patients with PCWP <15 mm Hg at rest (N=50): AUC 0.74b to detect PCWP ≥25 mm Hg | E/e′ does not sufficiently precise predict the exercise‐induced elevation of PCWP | |

| Andersen, 201348 | Prospective | Post myocardial infarction with LAVI >34 mL, 8<E/e′<15, LVEF 56±7% | 61 | Supine bicycle | Simultaneous |

↑ PCWP |

↓ Lateral, Septal, Mean |

n.s. | ··· | ··· | E/e′ does not reflect exercise‐induced changes in PCWP post‐MI patients with resting E/e′ in the intermediate range | PCWP ↑ and E/e′ ↓ |

| Clemmensen, 201637 | Prospectivea | Heart transplants, LVEF 65±1% | 57 | Semi‐supine bicycle | Simultaneous |

↑ PCWP |

↔? Mean |

··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | E/e′ change did not differ in patients with exercise elevated and not elevated LVFP |

| Interventions to decrease LVFP | ||||||||||||

| Hadano, 200734 | Prospectivea Consecutive | Patients undergoing cardiac surgery, LVEF 40±17% | 52 | Cardiac surgery | Consequentive |

↓ PCWP |

↑ Lateral, Septal |

Sign. | ··· | ··· | E/e′ does correlate with PCWP after cardiac surgery | PCWP ↓ and E/e′ ↑ |

| Serial or repeated measurements | ||||||||||||

| Sundereswaran, 199839 | Prospective | Heart transplants, LVEF 56±12% | 14 | Repeated measurements at unknown interval | Simultaneous |

↓↑ PCWP |

↓↑ Mean |

··· | Sign. |

To detect a change in PCWP ≥5 mm Hg: Se./Sp.: 77%/75% if change in E/e′ >2.5 |

E/e′ does estimate LVFP and track changes in LVFP | |

| Nagueh, 199935 | Prospectivea | HCM enrolled for ethanol septal reduction | 17 | Measurements repeated at the end of surgery | Simultaneous |

↓↑ Pre‐A |

↓↑ Lateral |

··· | Sign. | ··· | E/e′ does track changes in LVFP | |

| Dokainish, 200443 | Prospectivea Consecutive | ICU or CCU, LVEF 47±18% | 9 | Measurements repeated at 48 hours | Simultaneous |

↓↑ PCWP |

↓↑ Mean |

··· | Sign. | ··· | E/e′ does track changes in LVFP | |

| Mullens, 200951 | Prospective Consecutive | ICU (LVEF<30%) | 51 | Measurements repeated at 48 hours | Simultaneous |

↓↑ PCWP |

? Mean |

··· | n.s. | ··· | In advanced HF, E/e′ does not reliably predict LVFP | |

? indicates not clear from text; ↑ or ↓, statistically significant increase or decrease was measured in the cohort; ↔, no statistically significant change was measured in the cohort; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; ICU/CCU, intensive/critical care unit; Lateral, Septal, and Mean, E/e′lateral, E/e′septal, and E/e′mean; LAVI, left atrial volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVFP, left ventricular filling pressure; N, number of patients; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; pre‐A, left ventricular pre‐A wave pressure; Se./Sp., sensitivity and specificity; Sign./n.s., study reports that correlation coefficient is/is not statistically significant.

Based on our read.

Statistically significant value of AUC.

In patients with severe aortic stenosis (N=28)49 and in patients with recent myocardial infarction (N=61),48 the investigators concluded that E/e′ does not reflect exercise‐induced changes in PCWP.48, 49 Three studies measured E/e′ and PCWP before and after cardiovascular surgery.34, 35, 47 In 1 study, a strong correlation between E/e′lateral and PCWP was noted before and 30 days after cardiac surgery (coronary artery bypass grafting or aortic valve replacement) (N=52, LVEF 40±17%).34 Interestingly in these patients, E/e′septal increased whereas PCWP decreased after surgery.34 In a study of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (N=17), ethanol‐induced septal infarction caused changes in PCWP of either direction, which strongly correlated with changes in E/e′lateral.35 In patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (with E<A, NYHA class III‐IV, and preserved LVEF, N=61), both PCWP and E/e′ increased following pulmonary thromboendarterectomy.47 Another study reported a strong correlation between individual changes in PCWP and E/e′mean in 9 patients with differing LVEF in the intensive care unit following 2 days of treatment with diuretics and/or inotropes.43 However, in 51 patients with decompensated heart because of advanced systolic HF, no correlation was found between changes in E/e′mean and PCWP.51

Discussion

The major findings of our study are that there is lack of robust clinical evidence to support the use of E/e′ in response to physiological and/or pharmacological intervention to estimate LVFP changes and LV diastolic dysfunction. Furthermore, most of the studies are single center with limited sample size with nonuniform study methodologies and data reporting that does not allow for quantitative meta‐analysis of the studies.

Invasive LVFP measurements (primarily LV end diastolic pressure or PCWP as its surrogate) in response to altered physiological conditions provide incremental information about the LV function and stiffness.4 In proper context, it can be extremely useful in diagnosing diastolic dysfunction.4 Since some studies5, 35, 43, 52, 53 have suggested that echocardiographic E/e′ can be used to estimate LVFP quantitatively/semiquantitatively, there has been tremendous interest in evaluating changes in E/e′ to physiological and/or pharmacological interventions as a surrogate to changes in LVFP and therefore its potential use in assessing LV diastolic function.5, 6, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Recent meta‐analysis has demonstrated that E/e′ measurements at rest have limited diagnostic accuracy in evaluating LVFP in patients with preserved LVEF.20 In the present systematic review, we again noted absence of meaningful correlation (where reported) between E/e′ and LVFP at rest in preserved LVEF (Table S3). In contrast, for the reduced or mixed LVEF group, a stronger correlation between E/e′ and LVFP is reported (Table S4), which may be related to a wider range of E/e′ and LVFP (for instance, see Figure 4 in Nagueh et al54). However, other factors may also be playing an important role as Manouras et al30 demonstrated a higher correlation for the reduced LVEF group compared to preserved LVEF despite similar LVFP and E/e′ range of values in the 2 cohorts (see Table 3 and Figure 4, Manouras et al30). It is interesting to note that the recent American Society of Echocardiography guidelines propose a consensus‐based approach consisting of multiple parameters for evaluating diastolic function in preserved LVEF.10 Regarding posthemodynamic changes induced by exercise or physiological interventions, we note that there is no significant correlation between E/e′ and LVFP in preserved LVEF cohorts (Table S3). Moreover, most studies demonstrated worse correlation in mixed or reduced LVEF cohorts after exercise or physiological interventions (Table S4). A similar trend was also noticed in patients with specific cardiac conditions (Table S5).

For evaluating the relationship of change in E/e′ to changes in LVFP in response to exercise or physiological/pharmacological intervention, we find that there are only 2 studies with limited sample size that directly31 or indirectly32 support the use of E/e′ for the assessment of LVFP changes in HFpEF patients. In 12 patients, Talreja et al31 found a promising diagnostic value of specific exercise E/e′ cutoff (>15) to predict elevation of exercise PCWP (>20 mm Hg). Efstratiadis et al32 reported concordant reduction of E/e′ and LVFP following nesiritide infusion in 10 patients. Seven other studies24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 33 (cumulative N=429) found that E/e′ does not reliably reflect changes in LVFP in response to physiological or pharmacological intervention in preserved EF. For studies that evaluated mixed LVEF groups, results similar to those of the preserved LVEF group were noted. Only 1 study25 demonstrated a clinically meaningful relationship and diagnostic characteristics of E/e′ in estimating elevated LVFP with exercise and reduced exercise capacity. No consistent trends were found in other studies with mixed groups. Also, in specific cardiac conditions we did not find consistent trends across the studies. In the present study we did not evaluate the prognostic value or the pathognomonic mechanisms that may be attributed to the lack of reported relationships with exercise or other interventions of changes in E/e′ and LVFP. It is well recognized7 that LVFP may increase in diastolic dysfunction on invasive measurements. However, E/e′ measurements did not demonstrate a predictable relationship, which may be attributable to the small sample size of individual studies with relatively heterogeneous LV mechanics. This requires further exploration in future studies.

A number of guidelines/tools such as STARD55 and QUADAS56 have been developed for evaluating diagnostic test accuracy studies. As evident from our data tables, because of a limited number of studies, limited sample size, and nonuniform methodologies and data reporting, performing such an analysis would not substantially alter our results. Here we are unable to quantify effects of publication bias due to lack of consistent findings and limited studies. However, this is unlikely to affect the overall conclusions.

In summary, our review indicates that there is inadequate evidence for using E/e′ for estimating LVFP changes in response to exercise/other physiological interventions. Well‐designed prospective multicenter studies are required for evaluation and validation before recommending it for clinical and research purposes.

Sources of Funding

The study was supported by a National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant R01‐HL104018. The funding organizations did not have any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

Table S2. Full‐Text Studies Excluded After Evaluation (No Data of Interest)

Table S3. Detailed Summary of Studies With Subjects With LVEF ≥50%

Table S4. Detailed Summary of Studies With Subjects With Mixed or Reduced LVEF

Table S5. Detailed Summary of Studies With Subjects With Specific Cardiac Conditions

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e004766. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004766.)

References

- 1. Steinberg BA, Zhao X, Heidenreich PA, Peterson ED, Bhatt DL, Cannon CP, Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC. Trends in patients hospitalized with heart failure and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: prevalence, therapies, and outcomes. Circulation. 2012;126:65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kane GC, Karon BL, Mahoney DW, Redfield MM, Roger VL, Burnett JC Jr, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ. Progression of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and risk of heart failure. JAMA. 2011;306:856–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paulus WJ, Tschope C, Sanderson JE, Rusconi C, Flachskampf FA, Rademakers FE, Marino P, Smiseth OA, De Keulenaer G, Leite‐Moreira AF, Borbely A, Edes I, Handoko ML, Heymans S, Pezzali N, Pieske B, Dickstein K, Fraser AG, Brutsaert DL. How to diagnose diastolic heart failure: a consensus statement on the diagnosis of heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction by the Heart Failure and Echocardiography Associations of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2539–2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nagueh SF, Appleton CP, Gillebert TC, Marino PN, Oh JK, Smiseth OA, Waggoner AD, Flachskampf FA, Pellikka PA, Evangelista A. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:107–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Bohm M, Dickstein K, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fonseca C, Gomez‐Sanchez MA, Jaarsma T, Kober L, Lip GY, Maggioni AP, Parkhomenko A, Pieske BM, Popescu BA, Ronnevik PK, Rutten FH, Schwitter J, Seferovic P, Stepinska J, Trindade PT, Voors AA, Zannad F, Zeiher A. ESC, guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1787–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Borlaug BA, Nishimura RA, Sorajja P, Lam CS, Redfield MM. Exercise hemodynamics enhance diagnosis of early heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:588–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Erdei T, Smiseth OA, Marino P, Fraser AG. A systematic review of diastolic stress tests in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, with proposals from the EU‐FP7 MEDIA study group. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:1345–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dorfs S, Zeh W, Hochholzer W, Jander N, Kienzle RP, Pieske B, Neumann FJ. Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure during exercise and long‐term mortality in patients with suspected heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:3103–3112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, Byrd BF III, Dokainish H, Edvardsen T, Flachskampf FA, Gillebert TC, Klein AL, Lancellotti P, Marino P, Oh JK, Popescu BA, Waggoner AD. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016;29:277–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pal N, Sivaswamy N, Mahmod M, Yavari A, Rudd A, Singh S, Dawson DK, Francis JM, Dwight JS, Watkins H, Neubauer S, Frenneaux M, Ashrafian H. Effect of selective heart rate slowing in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2015;132:1719–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maier LS, Layug B, Karwatowska‐Prokopczuk E, Belardinelli L, Lee S, Sander J, Lang C, Wachter R, Edelmann F, Hasenfuss G, Jacobshagen C. RAnoLazIne for the treatment of diastolic heart failure in patients with preserved ejection fraction: the RALI‐DHF proof‐of‐concept study. JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1:115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kosmala W, Holland DJ, Rojek A, Wright L, Przewlocka‐Kosmala M, Marwick TH. Effect of If‐channel inhibition on hemodynamic status and exercise tolerance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1330–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Edelmann F, Wachter R, Schmidt AG, Kraigher‐Krainer E, Colantonio C, Kamke W, Duvinage A, Stahrenberg R, Durstewitz K, Loffler M, Dungen HD, Tschope C, Herrmann‐Lingen C, Halle M, Hasenfuss G, Gelbrich G, Pieske B. Effect of spironolactone on diastolic function and exercise capacity in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the Aldo‐DHF randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309:781–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ito H, Ishii K, Iwakura K, Nakamura F, Nagano T, Takiuchi S. Impact of azelnidipine treatment on left ventricular diastolic performance in patients with hypertension and mild diastolic dysfunction: multi‐center study with echocardiography. Hypertens Res. 2009;32:895–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hammoudi N, Achkar M, Laveau F, Boubrit L, Djebbar M, Allali Y, Komajda M, Isnard R. Left atrial volume predicts abnormal exercise left ventricular filling pressure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:1089–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen SM, He R, Li WH, Li ZP, Chen BX, Feng XH. Relationship between exercise induced elevation of left ventricular filling pressure and exercise intolerance in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2016;13:546–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kosmala W, Jellis CL, Marwick TH. Exercise limitation associated with asymptomatic left ventricular impairment: analogy with stage B heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:257–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huynh QL, Kalam K, Iannaccone A, Negishi K, Thomas L, Marwick TH. Functional and anatomic responses of the left atrium to change in estimated left ventricular filling pressure. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1428–1433.e1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sharifov OF, Schiros CG, Aban I, Denney TS, Gupta H. Diagnostic accuracy of tissue Doppler index E/e' for evaluating left ventricular filling pressure and diastolic dysfunction/heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002530 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Galderisi M, Lancellotti P, Donal E, Cardim N, Edvardsen T, Habib G, Magne J, Maurer G, Popescu BA. European multicentre validation study of the accuracy of E/e' ratio in estimating invasive left ventricular filling pressure: EURO‐FILLING study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15:810–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Previtali M, Chieffo E, Ferrario M, Klersy C. Is mitral E/E' ratio a reliable predictor of left ventricular diastolic pressures in patients without heart failure? Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;13:588–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Penicka M, Bartunek J, Trakalova H, Hrabakova H, Maruskova M, Karasek J, Kocka V. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in outpatients with unexplained dyspnea: a pressure‐volume loop analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1701–1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Santos M, Rivero J, McCullough SD, West E, Opotowsky AR, Waxman AB, Systrom DM, Shah AM. E/e' ratio in patients with unexplained dyspnea: lack of accuracy in estimating left ventricular filling pressure. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:749–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burgess MI, Jenkins C, Sharman JE, Marwick TH. Diastolic stress echocardiography: hemodynamic validation and clinical significance of estimation of ventricular filling pressure with exercise. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1891–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bhella PS, Pacini EL, Prasad A, Hastings JL, Adams‐Huet B, Thomas JD, Grayburn PA, Levine BD. Echocardiographic indices do not reliably track changes in left‐sided filling pressure in healthy subjects or patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:482–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chan AK, Govindarajan G, Del Rosario ML, Aggarwal K, Dellsperger KC, Chockalingam A. Dobutamine stress echocardiography Doppler estimation of cardiac diastolic function: a simultaneous catheterization correlation study. Echocardiography. 2011;28:442–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Firstenberg MS, Levine BD, Garcia MJ, Greenberg NL, Cardon L, Morehead AJ, Zuckerman J, Thomas JD. Relationship of echocardiographic indices to pulmonary capillary wedge pressures in healthy volunteers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1664–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maeder MT, Thompson BR, Brunner‐La Rocca HP, Kaye DM. Hemodynamic basis of exercise limitation in patients with heart failure and normal ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:855–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Manouras A, Nyktari E, Sahlen A, Winter R, Vardas P, Brodin LA. The value of E/Em ratio in the estimation of left ventricular filling pressures: impact of acute load reduction: a comparative simultaneous echocardiographic and catheterization study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;166:589–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Talreja DR, Nishimura RA, Oh JK. Estimation of left ventricular filling pressure with exercise by Doppler echocardiography in patients with normal systolic function: a simultaneous echocardiographic‐cardiac catheterization study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2007;20:477–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Efstratiadis S, Michaels AD. Acute hemodynamic effects of intravenous nesiritide on left ventricular diastolic function in heart failure patients. J Card Fail. 2009;15:673–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Choi S, Shin JH, Park WC, Kim SG, Shin J, Lim YH, Lee Y. Two distinct responses of left ventricular end‐diastolic pressure to leg‐raise exercise in euvolemic patients with exertional dyspnea. Korean Circ J. 2016;46:350–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hadano Y, Murata K, Tanaka N, Muro A, Akagawa E, Tanaka T, Kunichika H, Matsuzaki M. Ratio of early transmitral velocity to lateral mitral annular early diastolic velocity has the best correlation with wedge pressure following cardiac surgery. Circ J. 2007;71:1274–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nagueh SF, Lakkis NM, Middleton KJ, Spencer WH III, Zoghbi WA, Quinones MA. Doppler estimation of left ventricular filling pressures in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1999;99:254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Egstrup M, Gustafsson I, Andersen MJ, Kistorp CN, Schou M, Tuxen CD, Moller JE. Haemodynamic response during low‐dose dobutamine infusion in patients with chronic systolic heart failure: comparison of echocardiographic and invasive measurements. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14:659–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Clemmensen TS, Eiskjaer H, Logstrup BB, Mellemkjaer S, Andersen MJ, Tolbod LP, Harms HJ, Poulsen SH. Clinical features, exercise hemodynamics, and determinants of left ventricular elevated filling pressure in heart‐transplanted patients. Transpl Int. 2016;29:196–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meluzin J, Hude P, Krejci J, Spinarova L, Podrouzkova H, Leinveber P, Dusek L, Soska V, Tomandl J, Nemec P. Noninvasive prediction of the exercise‐induced elevation in left ventricular filling pressure in post‐heart transplant patients with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2013;18:63–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sundereswaran L, Nagueh SF, Vardan S, Middleton KJ, Zoghbi WA, Quinones MA, Torre‐Amione G. Estimation of left and right ventricular filling pressures after heart transplantation by tissue Doppler imaging. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Marchandise S, Vanoverschelde JL, D'Hondt AM, Gurne O, Vancraeynest D, Gerber B, Pasquet A. Usefulness of tissue Doppler imaging to evaluate pulmonary capillary wedge pressure during exercise in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:2036–2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ritzema JL, Richards AM, Crozier IG, Frampton CF, Melton IC, Doughty RN, Stewart JT, Eigler N, Whiting J, Abraham WT, Troughton RW. Serial Doppler echocardiography and tissue Doppler imaging in the detection of elevated directly measured left atrial pressure in ambulant subjects with chronic heart failure. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:927–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chiang SJ, Daimon M, Ishii K, Kawata T, Miyazaki S, Hirose K, Ichikawa R, Miyauchi K, Yeh MH, Chang NC, Daida H. Assessment of elevation of and rapid change in left ventricular filling pressure using a novel global strain imaging diastolic index. Circ J. 2014;78:419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dokainish H, Zoghbi WA, Lakkis NM, Al‐Bakshy F, Dhir M, Quinones MA, Nagueh SF. Optimal noninvasive assessment of left ventricular filling pressures: a comparison of tissue Doppler echocardiography and B‐type natriuretic peptide in patients with pulmonary artery catheters. Circulation. 2004;109:2432–2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gibby C, Wiktor DM, Burgess M, Kusunose K, Marwick TH. Quantitation of the diastolic stress test: filling pressure vs. diastolic reserve. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14:223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weeks SG, Shapiro M, Foster E, Michaels AD. Echocardiographic predictors of change in left ventricular diastolic pressure in heart failure patients receiving nesiritide. Echocardiography. 2008;25:849–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yamada H, Kusunose K, Nishio S, Bando M, Hotchi J, Hayashi S, Ise T, Yagi S, Yamaguchi K, Iwase T, Soeki T, Wakatsuki T, Sata M. Pre‐load stress echocardiography for predicting the prognosis in mild heart failure. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:641–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gurudevan SV, Malouf PJ, Auger WR, Waltman TJ, Madani M, Raisinghani AB, DeMaria AN, Blanchard DG. Abnormal left ventricular diastolic filling in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: true diastolic dysfunction or left ventricular underfilling? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1334–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Andersen MJ, Ersboll M, Gustafsson F, Axelsson A, Hassager C, Kober L, Boesgaard S, Pellikka PA, Moller JE. Exercise‐induced changes in left ventricular filling pressure after myocardial infarction assessed with simultaneous right heart catheterization and Doppler echocardiography. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2803–2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dalsgaard M, Kjaergaard J, Pecini R, Iversen KK, Kober L, Moller JE, Grande P, Clemmensen P, Hassager C. Left ventricular filling pressure estimation at rest and during exercise in patients with severe aortic valve stenosis: comparison of echocardiographic and invasive measurements. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Goebel B, Luthardt E, Schmidt‐Winter C, Otto S, Jung C, Lauten A, Figulla HR, Gummert JF, Poerner TC. Echocardiographic evaluation of left ventricular filling pressures validated against an implantable left ventricular pressure monitoring system. Echocardiography. 2011;28:619–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mullens W, Borowski AG, Curtin RJ, Thomas JD, Tang WH. Tissue Doppler imaging in the estimation of intracardiac filling pressure in decompensated patients with advanced systolic heart failure. Circulation. 2009;119:62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ommen SR, Nishimura RA, Appleton CP, Miller FA, Oh JK, Redfield MM, Tajik AJ. Clinical utility of Doppler echocardiography and tissue Doppler imaging in the estimation of left ventricular filling pressures: a comparative simultaneous Doppler‐catheterization study. Circulation. 2000;102:1788–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nagueh SF, Mikati I, Kopelen HA, Middleton KJ, Quinones MA, Zoghbi WA. Doppler estimation of left ventricular filling pressure in sinus tachycardia. A new application of tissue Doppler imaging. Circulation. 1998;98:1644–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nagueh SF, Middleton KJ, Kopelen HA, Zoghbi WA, Quinones MA. Doppler tissue imaging: a noninvasive technique for evaluation of left ventricular relaxation and estimation of filling pressures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1527–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bossuyt PM, Cohen JF, Gatsonis CA, Korevaar DA. STARD 2015: updated reporting guidelines for all diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, Leeflang MM, Sterne JA, Bossuyt PM. QUADAS‐2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

Table S2. Full‐Text Studies Excluded After Evaluation (No Data of Interest)

Table S3. Detailed Summary of Studies With Subjects With LVEF ≥50%

Table S4. Detailed Summary of Studies With Subjects With Mixed or Reduced LVEF

Table S5. Detailed Summary of Studies With Subjects With Specific Cardiac Conditions