Abstract

Background

Pediatric patients awaiting orthotopic heart transplantation frequently require bridge to transplantation (BTT) with mechanical circulatory support. Posttransplant survival outcomes and predictors of mortality have not been thoroughly described in the modern era using a large-scale analysis.

Methods

The United Network for Organ Sharing database was reviewed to identify pediatric heart transplant recipients from 2005 through 2012. Patients were stratified into three groups: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), ventricular assist device (VAD), and direct transplantation (DTXP). The primary outcome was posttransplant survival.

Results

Two thousand seven hundred seventy-seven pediatric patients underwent orthotopic heart transplantation. There were 617 patients who required BTT with mechanical circulatory support (22.2%), of whom there were 428 VAD BTT (69.4%) and 189 ECMO BTT (30.6%). An increase in VAD use was observed during the study period (p < 0.0001). Compared with DTXP, patients in the ECMO BTT group had a lower median age (<1 versus 5 years; p < 0.0001) and were significantly smaller (8 versus 14 kg; p < 0.001), whereas patients in the VAD BTT group were older (8 versus 5 years; p = 0.0002) and larger (24 versus 14 kg; p < 0.001). Actuarial survival was greater in the DTXP group compared with ECMO BTT, but similar to VAD BTT at 30 days and 1, 3, and 5 years. However, this survival difference was lost after censoring the first 4 months after transplant. In multivariable analysis, when restricted to the first 4 months of survival, independent predictors for mortality were ECMO BTT, age, diagnosis, and functional status, whereas VAD BTT was not.

Conclusions

Pediatric patients with DTXP or VAD BTT have equivalent posttransplant survival. However, those requiring ECMO BTT have inferior early post-transplant survival compared with those receiving DTXP.

Heart transplantation remains the definitive, gold standard treatment for pediatric patients with end-stage heart failure. Because of the scarcity of available donor organs, in conjunction with a growing number of children diagnosed with end-stage heart failure, the list of pediatric patients awaiting heart transplantation continues to grow, and the waiting list mortality remains the highest of any group in need of solid organ transplantation [1, 2].

To achieve survival to heart transplantation, the use of mechanical circulatory support (MCS) is often required in a bridge to transplantation (BTT) strategy. Patients may be bridged using ventricular assist devices (VADs) or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) [3]. Several large single-center [4–6] and multicenter [7–9] studies, as well as a prospective randomized controlled trial [10], have reported their experience using MCS as a BTT. However, the impact of MCS as a BTT on post-transplant survival has not been thoroughly examined. The primary aim of this study was to estimate differences in posttransplant survival of pediatric patients requiring MCS as a BTT in the modern era compared with patients who underwent direct transplantation (DTXP).

Patients and Methods

The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database was queried to identify pediatric cardiac transplant patients (≤18 years of age) between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2012. Patients were categorized as either DXTP or MCS as a bridge to transplant with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO BTT) or with a ventricular assist device (VAD BTT). Additionally, we performed a secondary analysis with a fourth level of exposure for patients who were initially placed on ECMO before undergoing a VAD implantation during the listing period (“bridge to VAD”). These patients were identified in the UNOS registry as those requiring ECMO support at “time of listing” but VAD support at “time of transplant.”

Variables were first investigated for frequency, distribution, and amount of missing data. The primary exposure variable was defined as one of three levels of BTT: DXTP, VAD, or ECMO. The primary outcome variable was 5-year survival. All potential confounders were selected a priori and investigated using a three-step process. First, the crude association between BTT type and survival was estimated. Stratified analyses were then run adjusting for one additional covariate entered as a categorical variable (diagnosis, medical condition at transplant, functional status at transplant based on the Lansky score [11], and age in years). Variables that changed the crude hazard ratio (HR) by more than 10% were considered potential confounders and further investigated in multivariable Cox models. Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazards regression were used for time-to-event analysis. Multivariable Cox models were built by including all potential confounders and then removing one variable at a time and comparing the Akaike’s information criterion for nested models. The final model with the best fit was then tested for violations of the proportionality assumption using martingale residuals. Marked deviations from the proportional hazards assumption were observed. Extended multivariable Cox models that incorporated interaction terms for the variables that violated the assumption were then investigated; however, this method did not fully correct for the violations. We also investigated accelerated time to failure models using a Weibull distribution, which yielded similar results to the Cox models. As a final step, separate Cox models were fit, one to the data for the first 4 months after transplant and one to the data beginning at 4 months after transplant. These models did not violate the proportional hazards assumption based on the martingale residuals and therefore were the included analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Graphs were created using Prism Graphpad version 5.0 graphical software (La Jolla, CA).

Results

Recipient Characteristics

Two thousand seven hundred seventy-seven pediatric patients who underwent orthotopic heart transplantation were identified. Recipient characteristics are presented in Table 1. There were 2,160 patients who underwent DTXP and 617 patients requiring a BTT with MCS (22.2%). While the proportion of patients bridged with VAD compared with those with ECMO was nearly equivalent in 2005, we observed a steady trend toward the increased use of VAD throughout the study period (p < 0.0001; Fig 1). Of the 617 patients requiring a BTT with MCS, there were 428 in the VAD BTT group (69.4%) and 189 in the ECMO BTT group (30.6%). Compared with the DTXP group, the median age of patients in the ECMO group was younger (<1 versus 5 years) whereas the median age of patients in the VAD group was older (8 versus 5 years; p < 0.0001). The same relationship was observed for weight at time of transplant for the DTXP, ECMO BTT, and VAD BTT groups (14 versus 8 versus 24 kg, respectively; p < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Pediatric Heart Transplant Recipientsa

| Characteristic | DTXP (n = 2,160) | ECMO (n = 189) | VAD (n = 428) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y (median and IQR) | 5 (0–13) | 0 (0–6) | 8 (1–14) | <0.0001b |

| Weight, kg (median and IQR) | 14 (7–43) | 8 (4–21) | 24 (11–52) | <0.0001b |

| Female | 1007 (47) | 85 (45) | 191 (45) | 0.71c |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Congenital defect, s/p surgery | 729 (34) | 83 (44) | 64 (15) | <0.0001c |

| Idiopathic DCM | 514 (24) | 32 (17) | 200 (47) | |

| Idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy | 112 (5) | 6 (3) | 6 (1) | |

| DCM s/p myocarditis | 49 (2) | 12 (6) | 42 (10) | |

| HLHS | 74 (3) | 7 (4) | 1 (<1) | |

| Other | 682 (32) | 49 (26) | 115 (27) | |

| Days on waitlist (median and IQR) | 46 (16–106) | 13 (6–36) | 52 (23–102) | <0.0001b |

| Medical condition at transplant | ||||

| ICU | 951 (44) | 173 (92) | 317 (74) | <0.0001c |

| Hospitalized, non-ICU | 387 (18) | 8 (4) | 78 (18) | |

| Not hospitalized | 822 (38) | 8 (4) | 33 (8) | |

| Previous heart transplant | 166 (8) | 14 (7) | 7 (2) | <0.0001c |

| Functional status at transplant | ||||

| 10% | 98 (5) | 46 (24) | 72 (17) | <0.0001c |

| 20% | 60 (3) | 4 (2) | 24 (6) | |

| 30% | 65 (3) | 2 (1) | 29 (7) | |

| 40% | 199 (9) | 7 (4) | 59 (14) | |

| 50% | 124 (6) | 1 (1) | 23 (5) | |

| 60% | 253 (12) | 7 (4) | 52 (12) | |

| 70% | 137 (6) | 2 (1) | 22 (5) | |

| 80% | 175 (8) | 3 (2) | 29 (7) | |

| 90% | 165 (8) | 7 (4) | 20 (5) | |

| 100% | 145 (7) | 3 (2) | 15 (4) | |

| N/A (<1 year old) | 638 (30) | 98 (52) | 64 (15) | |

| Unknown | 101 (5) | 9 (5) | 19 (4) | |

| Ischemic time (median and IQR) (hours) | 3.5 (3–4) | 3.8 (3–4) | 3.4 (3–4) | 0.005b |

Data are number of patients (%) unless indicated.

p value by one-way median analysis.

p value by χ2 test.

DCM = dilated cardiomyopathy; DTXP = direct transplantation; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HLHS = hypoplastic left heart syndrome; ICU = intensive care unit; IQR = interquartile range; N/A = not available; s/p = status post; VAD = ventricular assist device.

Fig 1.

Percent of pediatric patients bridged to transplant using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO; dark gray bars) or ventricular assist device (VAD; light gray bars) support per year (Cochran–Armitage p for trend <0.0001).

The most common pretransplant diagnosis was a “congenital defect status-post surgery” in the ECMO BTT and DTXP groups (44.0% and 34.0%, respectively), whereas dilated cardiomyopathy was the most common diagnosis in the VAD BTT group (47.0%). The ECMO BTT group spent a median of 13 days on the waitlist, whereas the VAD BTT and DTXP groups spent 52 and 46 days, respectively (p < 0.0001). Finally, a greater number of patients in the ECMO BTT group had undergone a previous heart transplantation than those in the VAD BTT group (7% versus 2%; p < 0.0001).

Posttransplant Survival

Posttransplant survival with ECMO BTT was reduced at all times when compared with DTXP (30 days and 1, 3, and 5 years; Table 2, Fig 2). There was no difference when comparing VAD BTT and DTXP groups. Compared with the DTXP group, the unadjusted HR for mortality in the ECMO BTT group was 3.20 (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.49 to 4.11; < 0.0001), whereas the HR for the VAD BTT group was 1.21 (95% CI, 0.93 to 1.57; p = 0.15; Table 3).

Table 2.

Posttransplant Outcomes by Bridge to Transplant Typea

| Bridge Type | Survival

|

Postoperative Complications

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-Day | 1-Year | 3-Year | 5-Year | Stroke | Dialysis | |

| DTXP | 2073 (98) | 1615 (91) | 978 (79) | 472 (77) | 47 (2) | 100 (5) |

| ECMO | 147 (79) | 105 (61) | 73 (50) | 40 (35) | 14 (7) | 56 (30) |

| VAD | 389 (96) | 283 (90) | 137 (74) | 58 (49) | 25 (6) | 24 (6) |

Data are number of patients (%).

DTXP = direct transplantation; ECMO = extracorporeal oxygenation; VAD = ventricular membrane assist device.

Fig 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for the first 4 months after transplant by bridge to transplant type (Wilcoxon p < 0.0001). (DTXP = direct transplantation [black line]; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [red line]; VAD = ventricular assist device [blue line].)

Table 3.

Unadjusted Hazard Ratio for the Association Between Bridge to Transplant Type and Mortality

| Bridge Type | HR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| DTXP | 1.0 | … | |

| ECMO | 3.20 | 2.49–4.11 | <0.0001 |

| VAD | 1.21 | 0.93–1.57 | 0.15 |

CI = confidence interval; DTXP = direct transplantation; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HR = hazard ratio; VAD = ventricular assist device.

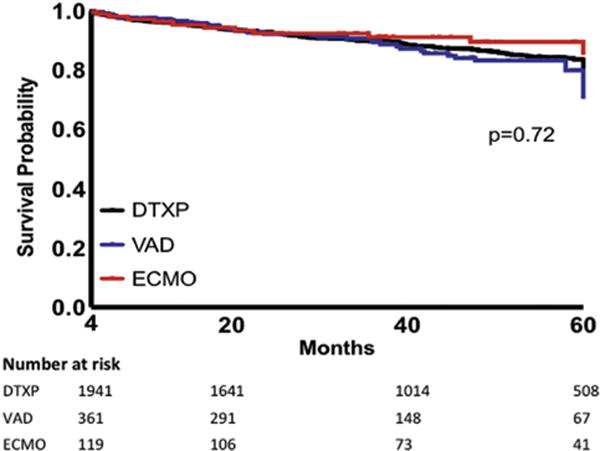

We observed significant violations of the proportional hazards assumption when mortality was analyzed for the entire follow-up period, which precluded accurate use of a single Cox model to identify adjusted HRs [12]. To overcome this limitation, separate Cox models were fit to cover two time periods, each of which individually satisfied the proportional hazards assumption (0 to 4 months and >4 months after transplant). When adjusted for diagnosis, functional status, and age, the adjusted HR for mortality restricted to the first 4 months after transplant was 2.77 in the ECMO BTT group compared with the DTXP group (95% CI, 2.12 to 3.61; p < 0.0001; Table 4). After censoring for the first 4 months after transplant, this mortality difference was lost at 1, 3, and 5 years (Table 5, Fig 3). This was confirmed with multivariable analysis adjusting for diagnosis, functional status, and age, in which the adjusted HR for mortality in the ECMO BTT group was 0.66 (95% CI, 0.36 to 1.20; p = 0.17) and for the VAD BTT group, 1.15 (95% CI, 0.81 to 1.61; p = 0.44; Table 5). The most common cause of death in the ECMO BTT group was multiorgan failure (9.3%), whereas in the VAD BTT group it was acute rejection (5%). Retransplantation was rarely performed in any group.

Table 4.

Adjusted Hazard Ratios for Time to Death by Bridge to Transplant Type Restricted to the First Four Months After Transplant (n = 2,777)

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| DTXP | 1.0 | … | … |

| ECMO | 2.77 | 2.12–3.61 | <0.0001 |

| VAD | 1.20 | 0.91–1.58 | 0.20 |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Other | 1.0 | … | … |

| Congenital defect, s/p surgery | 1.38 | 1.10–1.73 | 0.006 |

| Idiopathic DCM | 0.74 | 0.57–0.96 | 0.03 |

| Idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy | 0.88 | 0.51–1.51 | 0.64 |

| DCM s/p myocarditis | 0.70 | 0.41–1.20 | 0.20 |

| HLHS | 1.46 | 0.90–2.37 | 0.12 |

| Functional status at transplant | |||

| 100% | 1.0 | … | … |

| 90% | 1.46 | 0.76–2.81 | 0.26 |

| 80% | 1.58 | 0.83–3.00 | 0.16 |

| 70% | 1.60 | 0.82–3.11 | 0.17 |

| 60% | 1.35 | 0.73–2.51 | 0.34 |

| 50% | 1.17 | 0.57–2.40 | 0.67 |

| 40% | 1.49 | 0.80–2.77 | 0.21 |

| 30% | 1.99 | 0.99–4.02 | 0.05 |

| 20% | 2.47 | 1.23–4.95 | 0.01 |

| 10% | 3.20 | 1.77–5.77 | 0.0001 |

| N/A (<1 year old) | 2.04 | 1.11–3.76 | 0.02 |

| Unknown | 2.30 | 1.20–4.42 | 0.01 |

| Age, y | |||

| 0–1 | 1.0 | … | … |

| >1–5 | 0.78 | 0.53–1.15 | 0.21 |

| >5–10 | 0.59 | 0.38–0.91 | 0.02 |

| >10–15 | 1.01 | 0.71–1.45 | 0.94 |

| >15–18 | 1.44 | 0.98–2.12 | 0.06 |

CI = confidence interval; DCM = dilated cardiomyopathy; DTXP = direct transplantation; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HLHS = hypoplastic left heart syndrome; HR = hazard ratio; N/A = not available; s/p = status post; VAD = ventricular assist device.

Table 5.

Adjusted Hazard Ratios for Time to Death by Bridge to Transplant Type Excluding the First Four Months After Transplant (n = 2,421)

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| DTXP | 1.0 | … | … |

| ECMO | 0.66 | 0.36–1.20 | 0.17 |

| VAD | 1.15 | 0.81–1.61 | 0.44 |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Other | 1.0 | … | … |

| Congenital defect, s/p surgery | 1.39 | 1.03–1.88 | 0.03 |

| Idiopathic DCM | 0.96 | 0.70–1.31 | 0.80 |

| Idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy | 0.80 | 0.41–1.55 | 0.51 |

| DCM s/p myocarditis | 1.01 | 0.52–1.98 | 0.97 |

| HLHS | 1.17 | 0.58–2.38 | 0.67 |

| Functional status at transplant | |||

| 100% | 1.0 | … | … |

| 90% | 1.78 | 0.88–3.58 | 0.11 |

| 80% | 1.81 | 0.91–3.61 | 0.09 |

| 70% | 1.95 | 0.95–4.03 | 0.07 |

| 60% | 1.02 | 0.50–2.07 | 0.96 |

| 50% | 1.17 | 0.51–2.66 | 0.71 |

| 40% | 1.65 | 0.85–3.21 | 0.14 |

| 30% | 2.19 | 1.03–4.65 | 0.04 |

| 20% | 2.06 | 0.93–4.56 | 0.08 |

| 10% | 2.65 | 1.34–5.24 | 0.005 |

| N/A (<1 year old) | 1.38 | 0.69–2.77 | 0.37 |

| Unknown | 1.49 | 0.68–3.26 | 0.32 |

| Age, y | |||

| 0–1 | 1.0 | … | … |

| >1–5 | 0.72 | 0.45–1.17 | 0.19 |

| >5–10 | 0.46 | 0.27–0.80 | 0.006 |

| >10–15 | 0.96 | 0.62–1.48 | 0.85 |

| >15–18 | 1.44 | 0.92–2.27 | 0.11 |

CI = confidence interval; DCM = dilated cardiomyopathy; DTXP = direct transplantation; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HLHS = hypoplastic left heart syndrome; HR = hazard ratio; N/A = not available; s/p = status post; VAD = ventricular assist device.

Fig 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve by bridge to transplant type excluding the first 4 months after transplant (Wilcoxon p = 0.72). (DTXP = direct transplantation [black line]; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [red line]; VAD = ventricular assist device [blue line].)

Posttransplant Complications

When compared with the DTXP group, both the ECMO BTT and the VAD BTT groups had a higher incidence of stroke (Table 2). There was also a significantly higher incidence of renal failure requiring dialysis in the ECMO BTT group compared with the DTXP group.

Secondary Analysis of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation–to–Ventricular Assist Device Patients

There were 52 patients within the VAD BTT cohort who were undergoing ECMO at the time of listing before being transitioned to VAD (12.1%; 1.9% of all patients). These patients had a mean age of 6.6 ± 6.2 years and a mean weight of 26.8 ± 23.9 kg, and the most common diagnosis in this group was dilated cardiomyopathy (Table 6). There was no difference in short-term or midterm posttransplant survival of this group compared with the DTXP group, with an adjusted HR for mortality of 0.82 (95% CI, 0.36 to 1.87; p = 0.64) for the first 4 months after transplant and 0.52 (95% CI, 0.13 to 2.10; p = 0.36) for greater than 4 months after transplant.

Table 6.

Baseline Characteristics of Pediatric Patients Bridged to Heart Transplantation With Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation to Ventricular Assist Device Strategya

| Characteristic | ECMO to VAD (n = 52) |

|---|---|

| Age, y (median and IQR) | 3 (1–9) |

| Weight, kg (median and IQR) | 16 (10–31) |

| Female | 26 (50) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Congenital defect, s/p surgery | 13 (25) |

| Idiopathic DCM | 18 (35) |

| Idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy | 1 (2) |

| DCM s/p myocarditis | 10 (19) |

| HLHS | 0 (0) |

| Other | 10 (19) |

| Days on waitlist (median and IQR) | 59 (26–82) |

| Medical condition at transplant | |

| ICU | 47 (90) |

| Hospitalized, non-ICU | 3 (6) |

| Not hospitalized | 2 (4) |

| Previous heart transplant | 0 (0) |

| Functional status at transplant | |

| 10% | 15 (29) |

| 20% | 3 (6) |

| 30% | 2 (4) |

| 40% | 4 (8) |

| 50% | 2 (4) |

| 60% | 3 (6) |

| 70% | 4 (8) |

| 80% | 1 (2) |

| 90% | 5 (10) |

| 100% | 1 (2) |

| N/A (<1 year old) | 9 (17) |

| Unknown | 6 (6) |

| Ischemic time (median and IQR) (hours) | 3 (3–4) |

Data are number of patients (%) unless indicated.

DCM = dilated cardiomyopathy; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HLHS = hypoplastic left heart syndrome; ICU = intensive care unit; IQR = interquartile range; N/A = not available; s/p = status post; VAD = ventricular assist device.

Additionally, the HRs for mortality for the VAD BTT and ECMO BTT groups were not substantively changed after including the separate exposure level of ECMO to VAD, indicating that temporary use of ECMO as a bridge to VAD strategy does not confer an increased hazard of posttransplant mortality compared with patients in the DTXP group. When stratified by diagnosis, there was no difference in posttransplant survival during the follow-up period (p = 0.6 by log-rank test). Posttransplant survival and incidence of complications of patients undergoing a BTT with an ECMO-to-VAD strategy are listed in Table 7.

Table 7.

Posttransplant Outcomes by Diagnosis Among Pediatric Patients Bridged to Heart Transplantation Using an Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation to Ventricular Assist Device Strategya

| Diagnosis | Survival

|

Postoperative Complications

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-Day | 1-Year | 3-Year | 5-Year | Stroke | Dialysis | |

| Congenital defect, s/p surgery | 12 (92) | 6 (75) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 1 (8) |

| Idiopathic DCM | 18 (100) | 9 (90) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 3 (17) | 1 (6) |

| Idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | N/A | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| DCM s/p myocarditis | 9 (90) | 7 (88) | 5 (83) | 1 (50) | 1 (10) | 1 (10) |

| HLHS | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Other | 10 (100) | 8 (100) | 4 (100) | 2 (67) | 3 (30) | 0 (0) |

Data are number of patients (%).

DCM = dilated cardiomyopathy; HLHS = hypoplastic left heart syndrome; N/A = not available; s/p = status post.

Comment

In this retrospective review of pediatric heart transplant recipients in the modern era, patients in the ECMO BTT group had significantly worse survival at all times when compared with the DTXP group, whereas posttransplant survival in the VAD BTT and DTXP groups were equivalent. However, once censored for the first 4 months after transplant, the survival disadvantage seen in the ECMO BTT group was lost. To date, this is the largest post-transplant survival analysis in pediatric heart patients requiring a BTT with MCS. These findings are consistent with previous reports that have focused on outcomes in an earlier era (1998 to 2005) [13], small children and infants [14], or after the Berlin EXCOR randomized controlled trial [15].

We observed that VAD use as a BTT in children has increased during the last decade and, in total, was used in 22% of children listed for heart transplantation, consistent with findings from others [16, 17]. Furthermore, the use of VAD as a BTT was more likely to occur in older, larger children, and result in a posttransplant survival comparable with that of the DTXP group out to 5 years. The alternative, use of ECMO as a BTT, was more commonly observed in smaller, younger children and led to a substantially reduced posttransplant survival when compared with the DTXP group. Interestingly, when censoring for the first 4 months after transplant, our analysis revealed that the ECMO BTT group had similar mid-term outcomes as the DTXP group. Additionally, we observed no increased risk of mortality with the use of ECMO as a bridge to VAD strategy, which is often used in unstable adult patients before listing for transplantation and commitment to midterm VAD support but has not been reported in a cohort of pediatric heart transplantation patients.

A major limitation to VAD support in the smallest patients remains the lack of device availability [18]. Given the known thromboembolic, bleeding, and infectious complications associated with the use of ECMO [19, 20], it raises the question of whether the observed early mortality in the ECMO BTT group would be markedly reduced if durable VAD support were made available to the smallest children requiring MCS as a BTT. A number of devices currently under development [21], including the infant Jarvik 2000 [22] and PediaFlow [23], could help to answer this question if brought to clinical trial.

As survival data are well reported and maintained by the UNOS database, we were able to adequately explore our primary question, the effect of BTT with MCS on posttransplant survival. However, further inferences made in regard to patient characteristics, etiologic factors, or posttransplant complications were hindered by the limited granularity of the UNOS database. Linkage of the UNOS database to other sources of clinical data, such as The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Congenital Heart Surgery Database, may address this limited granularity of the UNOS database and provide enhanced information about patient characteristics, diagnosis, etiologic factors, and posttransplant complications [24, 25]. For example, data fields specifying congenital diagnosis or type of stroke (ischemic versus hemorrhagic) are not currently available [14]. It is important to note that although we controlled for covariates that confounded the relationship between BTT type and survival, there is the possibility of confounding by indication [26], which could not be adequately controlled for in this observational data set. Additionally, there were inconsistencies in the completeness of reported complication rates. As such, we limited our analysis of posttransplant complications to the incidence of stroke and dialysis requirement, as these represent major adverse events and were well reported. For instance, we were unable to discern whether the strokes that occurred were new strokes after transplant or had occurred previously while receiving VAD or ECMO support. Similarly, whether posttransplant dialysis was present before transplant was also not certain, which was recently reported in 3% of pediatric patients before transplant [27]. Answers to more specific questions related to diagnosis, timing and severity of complications, and factors contributing to mortality may be obtained through both (1) large single-center and multicenter studies, and (2) linkage of the UNOS database to other sources of clinical data.

In conclusion, these results demonstrate that when VAD is the MCS modality of choice for a BTT, pediatric patients have an equivalent midterm posttransplant survival as those undergoing DTXP. These findings underscore the importance of continued evolution of device technology and translation of safe, effective miniaturized VADs into clinical practice.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BTT

bridge to transplantation

- CI

confidence interval

- DTXP

direct transplantation

- ECMO

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- HR

hazard ratio

- MCS

mechanical circulatory support

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- VAD

ventricular assist device

References

- 1.Almond CS, Thiagarajan RR, Piercey GE, et al. Waiting list mortality among children listed for heart transplantation in the United States. Circulation. 2009;119:717–27. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.815712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mah D, Singh TP, Thiagarajan RR, et al. Incidence and risk factors for mortality in infants awaiting heart transplantation in the USA. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:1292–8. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dipchand AI, Kirk R, Edwards LB, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Sixteenth Official Pediatric Heart Transplantation Report—2013; focus theme: age. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:979–88. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobs JP, Asante-Korang A, O’Brien SM, et al. Lessons learned from 119 consecutive cardiac transplants for pediatric and congenital heart disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:1248–54. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.10.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen JM, Richmond ME, Charette K, et al. A decade of pediatric mechanical circulatory support before and after cardiac transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:344–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Botha P, Solana R, Cassidy J, et al. The impact of mechanical circulatory support on outcomes in paediatric heart transplantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;44:836–40. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morales DL, Almond CS, Jaquiss RD, et al. Bridging children of all sizes to cardiac transplantation: the initial multicenter North American experience with the Berlin Heart EXCOR ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassidy J, Dominguez T, Haynes S, et al. A longer waiting game: bridging children to heart transplant with the Berlin Heart EXCOR device—the United Kingdom experience. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:1101–6. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaushal S, Matthews KL, Garcia X, et al. A multicenter study of primary graft failure after infant heart transplantation: impact of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation on outcomes. Pediatr Transplant. 2014;18:72–8. doi: 10.1111/petr.12181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fraser CD, Jr, Jaquiss RD, Rosenthal DN, et al. Berlin Heart Study Investigators Prospective trial of a pediatric ventricular assist device. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:532–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lansky SB, List MA, Lansky LL, Ritter-Sterr C, Miller DR. The measurement of performance in childhood cancer patients. Cancer. 1987;60:1651–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19871001)60:7<1651::aid-cncr2820600738>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allison PD. Survival analysis using SAS A practical guide. 2nd. Carey, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies RR, Russo MJ, Hong KN, et al. The use of mechanical circulatory support as a bridge to transplantation in pediatric patients: an analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:421–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kilic A, Nelson K, Scheel J, Ravekes W, Cameron DE, Vricella LA. Outcomes of heart transplantation in small children bridged with ventricular assist devices. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:1420–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eghtesady P, Almond CS, Tjossem C, et al. Berlin Heart Investigators Post-transplant outcomes of children bridged to transplant with the Berlin Heart EXCOR Pediatric ventricular assist device. Circulation. 2013;128(11 Suppl 1):S24–31. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies RR, Haldeman S, McCulloch MA, Pizarro C. Ventricular assist devices as a bridge-to-transplant improve early post-transplant outcomes in children. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:704–12. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zafar F, Castleberry C, Khan MS, et al. Pediatric heart transplant waiting list mortality in the era of ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;34:82–8. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Connor MJ, Rossano JW. Ventricular assist devices in children. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2014;29:113–21. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delmo Walter EM, Alexi-Meskishvili V, Huebler M, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for intraoperative cardiac support in children with congenital heart disease. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010;10:753–8. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2009.220475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies RR, Haldeman S, McCulloch MA, Pizarro C. Creation of a quantitative score to predict the need for mechanical support in children awaiting heart transplant. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:675–82. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.04.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baldwin JT, Borovetz HS, Duncan BW, Gartner MJ, Jarvik RK, Weiss WJ. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute pediatric circulatory support program: a summary of the 5-year experience. Circulation. 2011;123:1233–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.978023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei X, Li T, Li S, et al. Pre-clinical evaluation of the infant Jarvik 2000 heart in a neonate piglet model. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:112–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson CA, Jr, Wearden PD, Kocyildirim E, et al. Platelet activation in ovines undergoing sham surgery or implant of the second generation PediaFlow pediatric ventricular assist device. Artif Organs. 2011;35:602–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2010.01124.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pasquali SK, Jacobs ML, Jacobs JP. Linking databases. In: Barach PR, Jacobs JP, Lipshultz SE, Laussen PC, editors. Pediatric and congenital cardiac care. Vol 1. Outcomes analysis. London: Springer-Verlag; 2014. pp. 395–402. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pasquali SK, Jacobs JP, Shook GJ, et al. Linking clinical registry data with administrative data using indirect identifiers: implementation and validation in the congenital heart surgery population. Am Heart J. 2010;160:1099–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stafford KA, Boutin M, Evans SR, Harris AD. Difficulties in demonstrating superiority of an antibiotic for multidrug-resistant bacteria in nonrandomized studies. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:1142–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vanderlaan RD, Manlhiot C, Edwards LB, Conway J, McCrindle BW, Dipchand AI. Risk factors for specific causes of death following pediatric heart transplant: an analysis of the registry of the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2015 Sep 18; doi: 10.1111/petr.12594. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/petr.12594 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]