Abstract

Neutrophils are well characterized as mediators of peripheral tissue damage in lupus, but it remains unclear whether they influence loss of self-tolerance in the adaptive immune compartment. Lupus neutrophils produce elevated levels of factors known to fuel autoantibody production, including interleukin-6 and B cell survival factors, but also reactive oxygen intermediates, which can suppress lymphocyte proliferation. In order to assess whether neutrophils directly influence the progression of auto-reactivity in secondary lymphoid organs (SLO), we characterized the localization and cell-cell contacts of splenic neutrophils at several stages in the progression of disease in the NZB/W murine model of lupus. Neutrophils accumulate in SLO over the course of lupus progression, preferentially localizing near T lymphocytes early in disease and B cells with advanced disease. RNA sequencing reveals that the splenic neutrophil transcriptional program changes significantly over the course of disease, with neutrophil expression of anti-inflammatory mediators peaking during early- and mid-stage disease, and evidence of neutrophil activation with advanced disease. To assess whether neutrophils exert predominantly protective or deleterious effects on loss of B cell self-tolerance in vivo, we depleted neutrophils at different stages of disease. Neutrophil depletion early in lupus resulted in a striking acceleration in the onset of renal disease, SLO germinal center formation, and auto-reactive plasma cell production. In contrast, neutrophil depletion with more advanced disease did not alter SLE progression. These results demonstrate a surprising temporal and context dependent role for neutrophils in restraining auto-reactive B cell activation in lupus.

Introduction

A central feature of lupus pathogenesis is production of autoantibodies that target multiple organ systems, resulting in chronic inflammation and, in severe cases, life-threatening organ damage. However, the mechanisms underlying the dysregulated adaptive immune response and progression of auto-reactivity in lupus remain incompletely characterized. Although B and T cells are well known to play a key role in SLE disease pathogenesis (1), the contribution of innate immune cells to disease is increasingly recognized (2). Neutrophils help orchestrate the outcome of immune responses by tailoring their effector program to an acute inflammatory response during infection, immunosuppression during chronic inflammatory states such as malignancy, or resolution of inflammation to promote healing. In SLE, neutrophils are known to mediate tissue damage and act as a source of self-nucleic acids that drive aberrant plasmacytoid dendritic cell (pDC) activation (3–5). Neutrophil-specific components are targeted by autoantibodies in 10–20% of SLE patients, likely due to a high neutrophil turnover rate, impaired dying cell clearance, and elevated propensity for extracellular trap formation (NETosis) (4–11). Because NETosis involves extravasation of nucleic acid and histone, this form of cell death may provide antigenic fuel for auto-reactive lymphocytes as well as interferon-producing pDC (3, 4). In vivo inhibition of NETosis with peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD4) inhibitors in murine lupus models ameliorates vascular, dermal, and renal tissue pathology and reduces systemic IFN-I signaling (10, 12).

In contrast, recent literature has contended that neutrophils in lupus—similar to neutrophils in other inflammatory conditions such as malignancy and sepsis—may acquire an immunosuppressive phenotype and restrain development of auto-reactivity (13, 14). In an amyloid-induced model of systemic autoimmunity, neutrophil production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) mediates suppression of systemic IFNγ levels and auto-antibody production (15). Additionally, in vitro co-culture of splenic neutrophils with B lymphocytes isolated from the NZB/W lupus model demonstrated that neutrophils can suppress B cell immunoglobulin production. Interestingly, neutrophil capacity for suppression of B cells was only apparent early in disease, suggesting that the neutrophil effector program may change with disease progression (16). Neutrophils may have different effects on adaptive immunity depending on the type of cell encounter. Thus, splenic neutrophils isolated in murine lupus were also able to suppress Treg differentiation in vitro, effects that should propagate autoimmunity (16–18). However, little is known about which immune cell types neutrophils interact with in vivo. It has been suggested that the predominant effect of neutrophil ROS in SLE may be protective, as was demonstrated by the finding of accelerated autoimmunity in MRL/lpr mice deficient in NADPH oxidase (NOX2, the enzyme responsible for oxidative burst in neutrophils) (19). Aside from ROS, circulating neutrophils in SLE also produce elevated amounts of pro-inflammatory mediators including interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor-necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), B-cell activation-factor (BAFF), and a proliferation inducing ligand (APRIL), factors known to promote adaptive immune dysregulation in lupus (4, 20–22). The cytokine profile of neutrophils in SLE remains incompletely characterized, particularly neutrophil production of anti-inflammatory factors such as TGFβ and IL-1RA.

Thus, although recent literature highlights that neutrophils influence the course of autoimmune disease, a more complete in vivo model is needed to reconcile the conflicting data pointing toward both pathogenic and regulatory effects on the adaptive immune compartment. We hypothesize here that neutrophils have the capacity for either deleterious or protective influence on the development of auto-reactivity, dependent on variables including stage and severity of disease, tissue localization, cellular interactions, and differences in inflammatory pathways driving SLE. Here, we assess whether neutrophils contribute directly to loss of B cell self-tolerance within secondary lymphoid tissues using the NZB/W murine model of lupus. Specifically, we characterize the localization, changing cellular contacts, and transcriptional program of splenic neutrophils at several stages during the course of autoimmunity. We find that neutrophils are in close proximity to splenic T and B lymphocytes and that lymphocyte-neutrophil contacts in the spleen change over the course of disease. Transcriptome profiling of splenic neutrophils demonstrates that neutrophils display a regulatory transcriptional program that is apparent during the initiation of disease, but is lost with advanced disease. Consistent with this result, neutrophil depletion early in disease resulted in a striking acceleration in the development of B cell auto-reactivity and renal proteinuria, a result that was not apparent in advanced disease. Collectively, our findings demonstrate that the neutrophil effector program and the nature of neutrophil impact on autoimmunity are strongly dependent on the stage and severity of disease, a critical consideration in the assessment of neutrophils as a potential therapeutic target in lupus.

Materials and methods

Mice

Female (NZBxNZW)F1 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and housed in the pathogen-free animal facility at the University of Rochester. All murine experiments were conducted in accordance with the policies established by the University of Rochester’s University Committee of Animal Resources and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Depletion of neutrophils with anti-Ly6G antibody

Female (NZBxNZW)F1 mice were injected intraperitoneally with neutrophil-depleting antibody anti-Ly6G (clone 1A8) (BioXCell) or ChromPure rat whole IgG isotype control (Jackson ImmunoResearch) using 500μg antibody per mouse every 2 days over the entirety of the indicated depletion periods. Mice were sacrificed 24 hours following the last antibody injection. Flow cytometry was used to verify the efficacy of neutrophil depletion.

Quantitation of renal pathology and serum anti-dsDNA

Proteinuria was quantitated using urinalysis reagent sticks (Teco Diagnostics). At sacrifice, kidneys were formalin fixed for histological analysis. Kidney sections (4 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Pathology was analyzed and scored in a blinded fashion (B.I.G.) (23). Briefly, the severity of glomerular, interstitial, and vascular lesions was determined on a scale of 0 to 4+. Multiple sections at a minimum of two different levels were examined, with each section typically containing >50 glomeruli and >25 blood vessels. Blood was collected by submandibular bleed and serum anti-dsDNA IgG concentration was determined by ELISA (Alpha Diagnostic International).

Flow cytometric quantitation of leukocyte subsets

Bone marrow was isolated by flushing of murine femur and tibia with RPMI 1640. Splenocytes were isolated by mechanical disaggregation. Erythrocytes were lysed with ammonium chloride buffer and leukocytes stained for FACS analysis with an LSR II (Becton-Dickinson). Lymphocyte populations were identified as CD3+CD4+CD8− (CD4+ T cells), CD3+CD4+CD8−CD25+FoxP3+ (Tregs), CD3+CD4+CD8−CXCR5hiPD1+ICOS+ (TFH cells), CD3−CD19+ (B cells), and CD19+CD95+Peanut-agglutinin+ (germinal center B cells). Myeloid cells were identified using B220+/CD4+/CD8+ cell exclusion and expression of CD11b+Gr-1hiLy6Cint (neutrophils) and CD11b+Gr-1lo−intCD11c−F4/80hi (monocytes/macrophages), which were further sub-gated into Ly6CloCX3CR1hiSSClo (M2 Mϕ) or Ly6ChiCX3CR1loSSClo (M1 Mϕ). Dead cells were excluded from all analyses using AQUA (Invitrogen). Antibodies used for flow cytometry: anti-CD3 (145-2C11), anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD8 (53-8.7), anti-CXCR5 (L138D7), anti-Foxp3 (150D), anti-CD25 (3C7), anti-PD1 (29F.1A12), anti-ICOS (15F9), anti-CD19 (6D5), anti-CD95 (SA367H8), anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), anti-Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), anti-Ly6C (HK1.4), anti-CX3CR1 (SA011F11).

Immunohistochemical characterization of secondary lymphoid organs (SLO)

Freshly isolated spleen was snap-frozen in OCT buffer and cut into 4μm sections for immunohistochemical staining. Sections were blocked (5% normal donkey serum/PBS), antibody-labeled, and mounted in Prolong Gold Antifade with DAPI (Life Technologies). Tissue sections were imaged with Zeiss Axioplan Microscope at 200× magnification for all images. Axiovision software (Zeiss) was used for morphometric analyses. Germinal centers were identified as PNA+PCNA+B220dim cell clusters and follicles as clusters of B220bright cells. The marginal zone (MZ) was identified as a line of MOMA+ staining in the peripheral region B220+ follicles. The extent of germinal center formation was calculated by dividing the total area occupied by GC by the total area of the tissue section. Neutrophil contacts with B and T lymphocytes in the spleen were quantitated based on the number of neutrophils (Ly6Gbright cells with PMN nuclear morphology) that appeared to be in contact with B220+ or CD3+ cells in the white pulp. Neutrophil localization relative to primary and secondary splenic follicles as well as to the marginal zone (MOMA+ line) was quantitated by positioning splenic follicles in a consistent fashion within the 200× field and measuring the distance between Ly6G+ cells and the follicle edge (B220+ cell clusters) or MOMA+ marginal zone line. Stains used for IHC: anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), PNA (peanut agglutinin), anti-PCNA (PC10), anti-MOMA (MOMA-2), anti-Ly6G (1A8), anti-CD3 (145-2C11).

ELISpot assay for antibody-secreting cells

ELISpot was performed as described previously (23, 24). Briefly, in order to detect anti-dsDNA-secreting cells, 96-well MultiScreen plates (Millipore) were coated with poly-L-lysine and incubated with calf thymus DNA. Plates were coated with goat anti-mouse IgG (Fc fragment specific, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) to detect total IgG-secreting cells. Cell suspensions from spleen, bone marrow and kidney were added to individual wells, starting with 5×105 cells in the top row and preforming a 2-fold serial dilution. Cells were incubated overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2. After incubation, plates were washed several times with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS, incubated with alkaline phosphatase-goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Southern Biotech), and finally developed with Vector Blue alkaline phosphatase substrate III kit (Vector Laboratories). Antibody-secreting cells were enumerated with a stereoscopic microscope (Cellar Technology Ltd.).

Purification of splenic neutrophils for RNA sequencing

Splenic neutrophils were purified by mechanical disaggregation of freshly isolated spleen without the use of erythrocyte lysis. Splenic neutrophils were isolated for RNAseq analysis pre-enrichment by magnetic negative selection (Miltenyi), followed by sorting of CD11bhiLy6GhiLy6bhiLy6Cint cells with doublet and dead (DAPI+) cell exclusion to obtain a purity of ≥97% CD11bhiLy6Ghi cells, as determined by post-sort analysis. Neutrophils were kept cold (at 4˚C) throughout the entire course of neutrophil isolation and handled gently to avoid mechanical activation. Antibodies used for FACS purification: anti-Ly6B (REA115), anti-Ly6C (HK1.4), anti-Ly6G (1A8), anti-CD11b (M1/70).

Low input RNA sequencing

Neutrophil total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (Qiagen) and RNA quality assessed with the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent) (n=6 mice per 3 age groups). 1ng of total RNA was pre-amplified with the SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input RNA Kit for Sequencing (Takara Bio USA). The quantity and quality of the subsequent cDNA was determined using the Qubit Flourometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the Agilent Bioanalyzer. 1ng of cDNA was used to generate Illumina compatible sequencing libraries with the NexteraXT (Illumina) library preparation kit. The amplified libraries were hybridized to the Illumina single end flow cell and amplified using the cBot (Illumina) at a concentration of 10pM per lane. Single-end reads of 100nt were generated for each sample and aligned to the organism specific reference genome. Sequenced reads were cleaned using Trimmomatic-0.32 before mapping to the mouse reference genome (GRCm38.p4) with STAR-2.4.2a. Raw read counts were obtained using HTSeq and gencode M6 mouse gene annotations. DESeq2 1.12.3 was used to perform data normalization. Following an expression level cutoff of 1 (rlog deseq norm counts), principle components analysis was performed using all transcripts. Additionally, a list of 130 genes of immunologic interest was compiled and differential analysis was conducted using deSeq. These include genes involved in neutrophil regulation of immune responses, both protective mediators and pro-inflammatory mediators, as well as genes involved in neutrophil responses to inflammation such as IFN regulated genes and cytokine signaling genes like the Stat family. The full transcriptome data set is available on GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; accession GSE97439).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis comparing among experimental groups was done using the Mann-Whitney U-test or Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA using GraphPad Prism and MultiExperiment Viewer software. Differential expression analysis of RNA sequencing data was conducted using a Benjamini-Hochberg correction (FDR≤0.05). Principal components analysis was conducted using JMP Pro 13. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Results

Neutrophils accumulate in the spleen and exhibit changing lymphocyte contacts during the progression of lupus

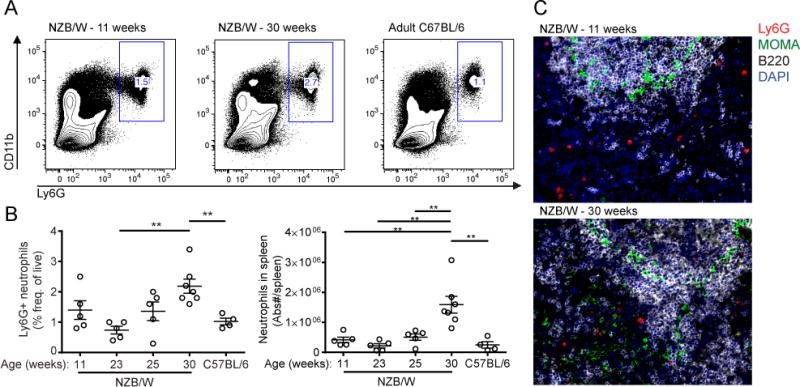

Under homeostatic conditions, neutrophils are present in SLO tissues at a frequency of 1–2% of total splenocytes, although their numbers can increase dramatically during an immune response (25). In order to characterize neutrophils in lupus and their impact on adaptive immunity, we first quantitated neutrophil infiltration of the spleen at several points over the course of lupus progression by FACS analysis of splenocytes from female NZB/W mice at 11, 23, 25, and 30 weeks of age. Between 23 weeks of age (around the onset of overt pathology, including proteinuria) and 30 weeks of age (advanced lupus), we observed a significant increase in both the frequency and total numbers of neutrophils infiltrating the spleen (Fig. 1A, 1B). Neutrophils were observed predominantly in the red pulp and interfollicular areas of the white pulp (Fig. 1C), and although we observe infiltration with the progression of disease, the average neutrophil proximity to B cell follicles did not change over the course of disease nor were they detected in GCs (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Neutrophils accumulate in the spleen over the course of lupus progression. (A) Representative FACS plots showing frequency of Ly6G+CD11b+ neutrophils as a fraction of CD45+ splenocytes. (B) Quantitation of frequency (of CD45+Live) and numbers of Ly6G+CD11b+ splenocytes cells by FACS (n=4–5mice/group). C57BL/6 mice are 15–20-week old female mice in (A) and (B). (C) Representative IHC of spleen showing neutrophil localization relative to the marginal zone (MOMA+). 200× Mag. Analysis was done as described in Materials and Methods. n=5 mice per group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 by unpaired Student’s t-test. Data shown are the mean ± s.e.m.

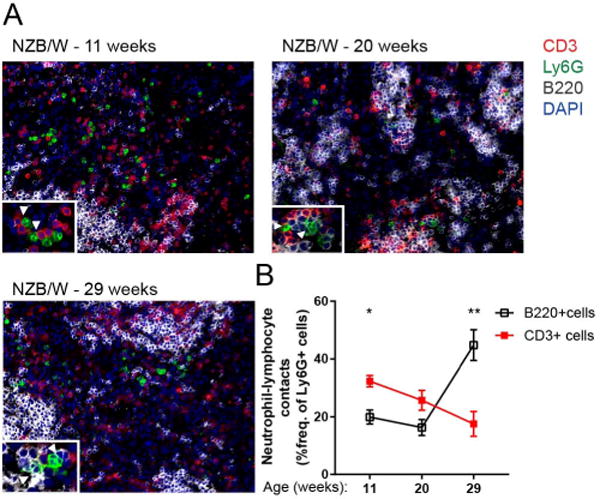

In order to address the hypothesis that neutrophils are directly interacting with splenic B and T lymphocytes, neutrophil contacts with B and T cells were quantitated by IHC of spleens isolated from 11, 20, and 29 week-old NZB/W mice. Neutrophils were observed in close contact with T and B lymphocytes in the splenic white pulp during all stages of disease (Fig. 2A). At 11 weeks, early in disease, the frequency of neutrophil contacts with T cells was 1.5-fold higher than contacts with B cells (Fig. 2B). By 29 weeks of age, this phenomenon is reversed, with nearly half of all Ly6G+ neutrophils in the white pulp in close contact with B220+ B cells, and only 20% of neutrophils in contact with CD3+ T cells. The changing frequency of neutrophil contacts with splenic lymphocytes over the course of disease suggests that the functional impact neutrophils have on splenic lymphocyte populations changes over the course of disease.

Figure 2.

Neutrophil contacts with splenic B and T lymphocytes in NZB/W spleen change over the progression of lupus. (A) Representative IHC showing neutrophil proximity to B220+ cells and CD3+ cells in lupus spleen at several stages in the progression of lupus. Insets show neutrophil localization in relation to CD3+ and B220+ cells. (B) Quantitation of neutrophils in contact with B220+ B cells and CD3+ T cells as a frequency of Ly6G+ cells per 200× field. Analysis was performed as described in Materials and Methods. n=5 mice per group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 by Mann-Whitney U-test comparing frequency of neutrophils in contact with B220+ B cells and frequency of neutrophils in contact with CD3+ T cells. Data shown are the mean ± s.e.m.

Analysis of the splenic neutrophil transcriptional program over the course of lupus progression

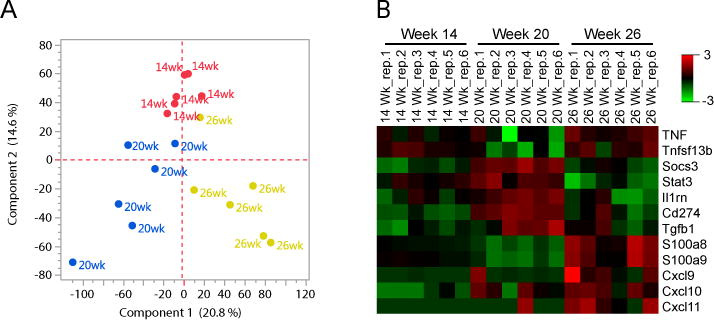

Because we observed significant changes in neutrophil frequency and localization relative to splenic B and T leukocytes in the spleen over the course of disease, we hypothesized that neutrophil function changes with disease progression. Because very little is known about the neutrophil effector program within the SLO in autoimmunity, we employed RNA sequencing as an unbiased approach to assess whether splenic neutrophils display a regulatory or pro-inflammatory transcriptional program, as well as determine whether this program changes over the course of disease. Neutrophils were pre-enriched and FACS sorted from NZB/W splenocytes at three time points, 14 weeks (early disease), 20 weeks (mid-disease), and 26 weeks (advanced disease) (26). Neutrophil mRNA was isolated and the transcriptome sequenced using an Illumina platform.

Principal components analysis of the entire neutrophil transcriptome revealed clear separation of neutrophils isolated at the three disease time points, indicating significant changes in the neutrophil transcriptional program with lupus progression (Fig. 3A). Differential expression analysis (using a significance cutoff of FDR<0.05) revealed several transcripts of immunologic interest (Fig. 3B), including TNFα (Tnf) and BAFF (Tnfsf13b), factors known to promote B cell auto-reactivity in SLE (27–29). Interestingly, these two factors show a relative decrease at 20 weeks of age, followed by an increase with more advanced disease (26 weeks) (Fig. 3B). Concomitantly, between 14 and 20 weeks, we observed an increase in pro-resolving and anti-inflammatory mediators including PD-L1 (Cd274), IL-1RA (Il1rn), and TGFβ (Tgfb1) (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that, during the onset and acceleration of auto-antibody production in NZB/W mice between 14 and 20 weeks of age, splenic neutrophils adopt a more regulatory transcriptional program.

Figure 3.

Transcriptional profile of splenic neutrophils is consistent with acquisition of a protective phenotype as auto-reactivity accelerates and loss of this phenotype in advanced disease. (A) Principle components analysis reveals differential gene expression (cutoff >1, norm (rlog) expression) over the course of disease. (B) Differential expression analysis was conducted for 130 select genes of immunologic interest based on neutrophil function and regulation of immune responses using deSeq. Expression heat map of normalized and rlog transformed mRNA counts quantitated via RNAseq for select genes that were differentially expressed among the 3 experimental groups (significance cutoff, FDR<0.05, ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis). n=6/group.

The increase in protective, anti-inflammatory mediators by 20 weeks coincides with an increase in Stat3 and Socs3, transcription factors involved in induction of an anti-inflammatory neutrophil phenotype in response to prolonged exposure to an inflammatory cytokine milieu (30, 31). It is notable that expression of genes associated with restraining inflammation, including PD-L1 (Cd274), IL-1RA (Il1rn), and TGFβ (Tgfb1) is down regulated between 20 and 26 weeks. Concomitantly, genes involved in neutrophil responses to inflammation and activation increased during this time frame. This includes the alarmins S100a8 and S100a9 (32), which have largely although not exclusively been associated with proinflammatory functions (33, 34). The interferon regulated chemokines, CXCL9 (MIG), CXCL10 (IP-10), and CXCL11 (I-TAC), important for T cell chemoattraction and activation were also significantly up-regulated (35) at 26 weeks (Fig. 3B). Based on these findings, we hypothesize that neutrophils acquire a protective transcriptional program between 14 and 20 weeks of age during the initial rise in auto-reactivity in NZB/W mice, but that the neutrophil phenotype shifts to a more activated state by 26 weeks (advanced disease).

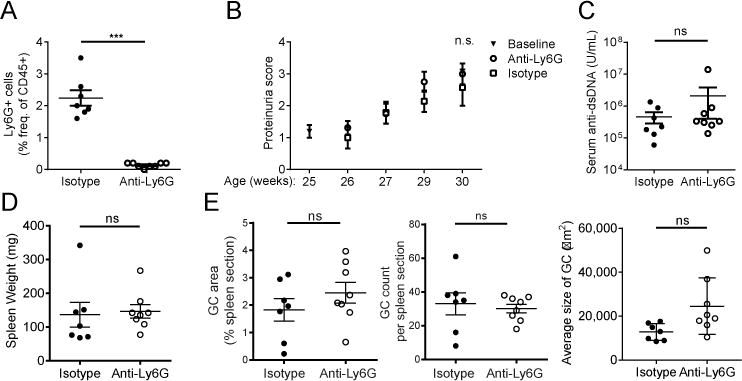

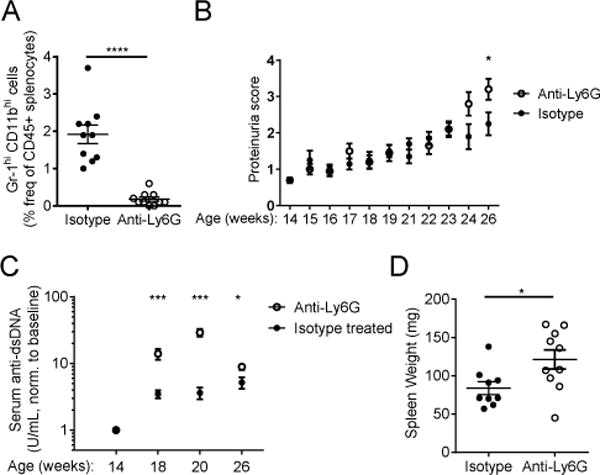

Depletion of neutrophils after auto-reactivity is established does not alter disease

In order to examine whether neutrophils exert predominantly protective or deleterious effects in modulation of auto-reactivity in lupus, we depleted neutrophils continuously in female NZB/W mice using an anti-Ly6G (1A8) antibody or isotype control (polyclonal rat IgG) over a period from 25–30 weeks of age. Anti-Ly6G injection effectively depleted neutrophils, as quantitated by FACS analysis of splenocytes isolated at sacrifice (30 weeks) (Fig. 4A). However, neutrophil depletion from 25–30 weeks of age did not result in a significant alteration in the progression of disease, including proteinuria, serum anti-dsDNA levels, splenomegaly, or germinal center formation (Fig. 4B–E). These results suggest that neutrophils are not required for progression of autoimmunity once active disease is well established.

Figure 4.

Continuous depletion of neutrophils from 25–30 weeks of age (established disease) does not alter lupus disease progression. (A) Quantitation of the efficacy of neutrophil depletion by FACS analysis of the frequency of Gr-1hiCD11bhi splenocytes at sacrifice (30 weeks of age) following 5 weeks of treatment with anti-Ly6G (1A8) or isotype control. (B) Progression of renal disease was assessed by quantitation of proteinuria. Scoring: 0.5=trace, 1=0.3g/L, 2=1g/L, 3=3g/L, 4>20g/L. (C) Quantitation of serum anti-dsDNA IgG by ELISA at sacrifice. (D) Splenomegaly was assessed at sacrifice. (E) Splenic germinal center size & number were quantitated by immunohistochemistry as described in Materials and Methods. n=10 mice per group. Outliers > x ®±2σ were excluded from analysis in (D) and (E). ‘ns’=not significant, ***p<0.001 by Mann-Whitney U-test. Data shown are the mean ± s.e.m.

Depletion of neutrophils during onset of lupus accelerates development of autoimmunity

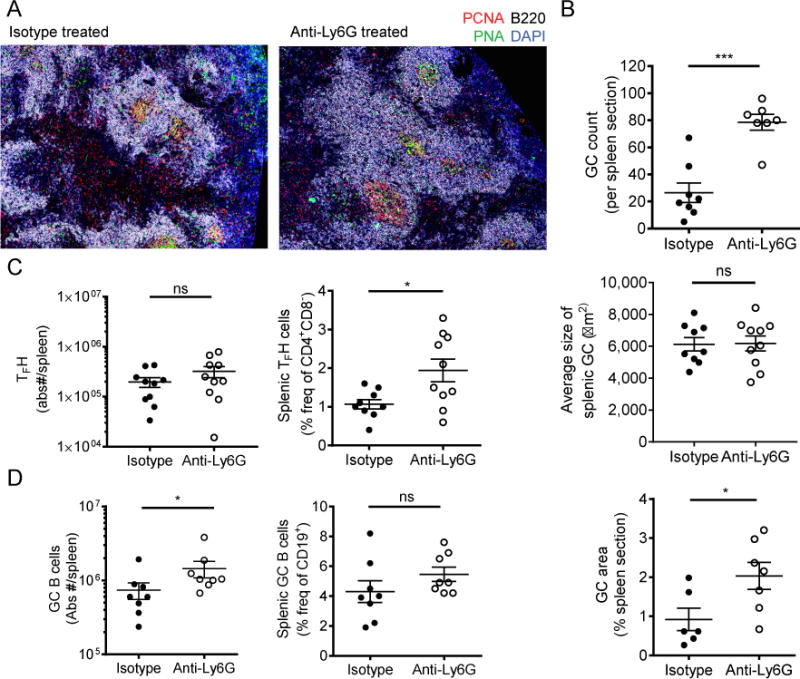

Although neutrophil depletion during established disease did not significantly alter the course, we next assessed whether neutrophils modulate adaptive immune responses at early stages of lupus. We depleted neutrophils as above, continuously in NZB/W mice over a 12-week period, from 14–26 weeks of age. The efficacy of depletion was assessed by FACS analysis of splenocytes (Fig. 5A), peripheral blood, and bone marrow (Supplemental Fig. 1A, 1B) isolated at sacrifice. Following anti-Ly6G treatment, mice exhibited an early and significant rise in plasma anti-dsDNA levels compared to isotype treated mice and developed proteinuria at an accelerated rate (Fig. 5B, 5C). Comparison of kidney histopathology did not reveal a statistically significant difference between anti-Ly6G- and isotype-treated groups (data not shown). Depletion during this 12-week period also resulted in significantly increased splenomegaly (Fig. 5D) and enhanced germinal center formation (Fig. 6A, 6B).

Figure 5.

Continuous depletion of neutrophils from 14–26 weeks of age (disease onset) accelerates development of auto-immunity. (A) Quantitation of the efficacy of neutrophil depletion by FACS analysis of the frequency of Gr-1hiCD11bhi splenocytes at sacrifice (26 weeks of age) following 12 weeks of treatment with anti-Ly6G (1A8) or isotype control. (B) Progression of renal disease was assessed by quantitation of proteinuria. Scoring: 0.5=trace, 1=0.3g/L, 2=1g/L, 3=3g/L, 4>20g/L. (C) Serum anti-dsDNA was quantitated by ELISA at baseline (immediately before depletion began), and after 4, 6, 12 weeks of antibody treatment. (D) Splenomegaly assessed at sacrifice. Outliers > x ®±2σ were excluded from analysis in (D) n=10 mice per group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by Mann-Whitney U-test. Data shown are the mean ± s.e.m.

Figure 6.

Germinal center formation is greatly accelerated with neutrophil depletion during the onset of autoimmunity. (A) Representative IHC of splenic germinal center formation in the isotype-treated versus anti-Ly6G-treated mice. 200× Mozaix. (B) IHC analysis was used to quantitate the extent of splenic germinal center formation. (C–D) FACS analysis was used to assess the frequency and absolute numbers of TFH cells and germinal center B cells (gating as described in Mat. & Met.). N=10 mice per group (B–D). Outliers > x+2d were excluded from analysis in (C) and (D). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by Mann-Whitney U-test. Data shown are the mean + s.e.m.

In order to assess whether neutrophil depletion alters the frequency of other immune cells, FACS analysis was used to quantitate the frequency and absolute numbers of M1 and M2 macrophages, GC B cells, T follicular helper cells (Tfh), and FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs). Consistent with the finding that GC formation is significantly augmented with anti-Ly6G treatment, we found a significant increase in numbers of GC B cells and frequency of Tfh cells following neutrophil depletion. The increase in Tfh frequency was not a global effect on T cells as there was no significant change in FoxP3+ Treg frequencies or absolute numbers in the spleen (Supplemental Fig. 2A). We also did not observe significant alterations in frequency of monocyte/macrophage populations or a shift in polarization to an M1 versus M2 phenotype following neutrophil depletion (Supplemental Fig. 2B, 2C). Together these results suggest that neutrophil depletion during the onset of lupus results in acceleration in the progression of auto-reactivity and magnitude of the adaptive immune dysregulation.

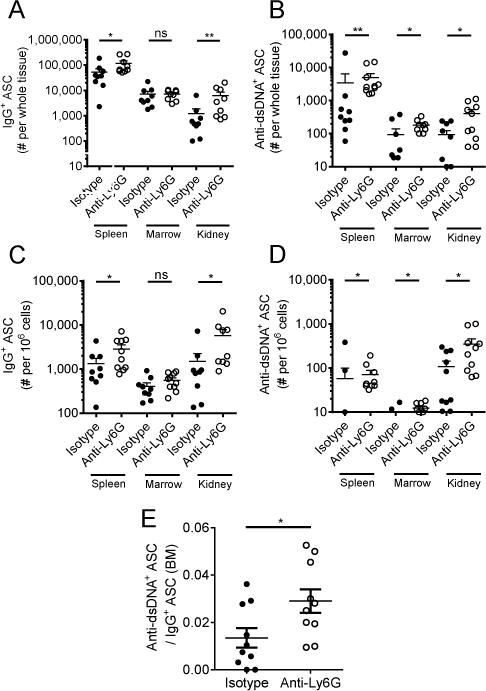

Because the accelerated rise in serum anti-dsDNA levels seen with neutrophil depletion (Fig. 5C) may be attributable to either antibody production or antibody clearance (including precipitation of immune complexes), we quantitated the production of both total IgG and anti-dsDNA IgG antibody secreting cells (ASC) directly by ELISPOT. Notably, total IgG and anti-dsDNA ASC increase significantly in spleen, kidney, and bone marrow following anti-Ly6G treatment (Fig. 7A–D). Additionally, there was enrichment in auto-reactive anti-dsDNA IgG ASC as a fraction of total IgG ASC in the bone marrow (Fig. 7E), suggesting that neutrophil depletion beginning at the onset of autoimmunity results in a systemic increase in auto-reactive B cells. Overall, these results indicate that neutrophils have a protective function during the early stages of lupus, but that this protective effect is lost by advanced stages of disease.

Figure 7.

Changes in frequency of anti-dsDNA+ and IgG+ antibody secreting cells (ASC) in spleen, kidney, and bone marrow. ELISPOT quantitation of (A) absolute number of IgG+ ASC per whole tissue, (B) absolute number of anti-dsDNA+IgG+ ASC per whole tissue, (C) frequency of IgG+ ASC per 106 cells, (D) frequency of anti-dsDNA+IgG+ ASC per 106 cells. (E) Anti-dsDNA IgG-secreting cells as a fraction of the total IgG-secreting cells in bone marrow. n=10 mice per group. Outliers > x ®±2σ were excluded from analysis. Zero value data points are not shown on graphs due to log scale but were included in the analysis. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by Mann-Whitney U-test. Data shown are the mean ± s.e.m.

Discussion

Neutrophils play a key role in the innate immune response to infections, but have increasingly been recognized to contribute to autoimmunity in diverse ways. Somewhat unexpectedly given the dominance of literature (mostly in vitro) supporting a pro-inflammatory role for neutrophils in lupus (2, 4, 8), we find that depletion of neutrophils early in murine SLE profoundly accelerates disease. This was evidenced by significant enhancement of splenic GC reactions and generation of autoantibody secreting cells in SLO. Notably, autoantibody secreting cells accumulated in target tissue (kidney) as well as the BM suggesting systemic effects of neutrophil absence on the autoimmune process. The findings that late neutrophil depletion had no impact on disease, shift in splenic neutrophil interactions from T cells to B cells, and change in transcriptional profile over the course of the disease highlights the plasticity in neutrophil roles in SLE. Our results indicate a dominantly suppressive effect for much of the disease likely mediated by direct interaction with T and B cells, whereas neutrophils acquire a more activated phenotype later in disease.

The finding that B cell autoimmunity is profoundly accelerated by neutrophil depletion starting early in disease strongly implicates a direct role for neutrophils in modulating the adaptive immune response in SLE. Although neutrophils have been shown to act in an immunosuppressive capacity during chronic inflammatory conditions such as malignancy or viral infection, the possibility that a pro-resolving or protective neutrophil is present in lupus has only recently been proposed (15, 16, 36–39). In an amyloid-induced lupus model neutrophil depletion worsened disease similar to our findings. A regulatory effect for neutrophils was suggested to be mediated by ROS inhibition of NK cell IFNγ production at local sites of inflammation (15). Another study demonstrated that Gr-1hiCD11b+ splenocytes suppress lupus pathogenesis in young male but not female NZB/W mice based on the finding that administration of anti-Gr-1 antibody in vivo increased anti-dsDNA antibody titers (16). Limitations of this study include the use of anti-Gr-1 antibody, which depletes both neutrophils and some monocyte populations (40–42). Ours is the first study in a well-accepted murine lupus model demonstrating that specific (anti-Ly6G) depletion of neutrophils accelerates disease via promotion of GC reactions.

Nonetheless, this finding should be considered in the context of literature implicating neutrophils as exerting a highly pathogenic impact on loss of tolerance in certain contexts. Neutrophils in both peripheral blood and bone marrow have been shown to express elevated amounts of BAFF, a factor known to underlie failure of auto-reactive B cell anergy (20, 27, 43, 44). Along these lines and in contrast to our findings, neutrophil depletion in a B6.Faslpr/J/Tnfrsf17−/− autoimmune model resulted in significant amelioration of autoimmunity, including reduced serum anti-dsDNA titers and splenic plasma cell frequency. This result depended on splenic neutrophil production of BAFF, which was shown in vitro to stimulate CD4+ T cell production of IFNγ—a critical mediator of auto-reactive germinal center formation (21, 44). The contrasting results in this model may be attributable to the strong dependence of the lupus phenotype on specific immune pathways, such as BAFF signaling. We do not rule out the possibility that neutrophils can augment the progression of auto-reactivity in the NZB/W model, particularly during advanced disease, where we observed a notable rise in transcription of BAFF and TNFα between 20 and 26 weeks. It is also possible that other neutrophil functions in addition to pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion, such as NETosis, are dominantly pro-inflammatory. On the other hand, it is interesting to note that when NETs were inhibited in the NZM lupus model vascular damage was ameliorated but anti-DNA antibodies actually did rise (10, 12), suggesting that even NETosis may have unexpected anti-inflammatory effects (45). It is also important to consider that the lack of effect of neutrophil depletion from 25–30 weeks of age in our experiments may be attributable to neutrophil effects being overwhelmed by a strong immune response and rapidly worsening autoimmunity in this period. Nonetheless, our findings clearly demonstrate that neutrophils are non-essential for progression of both auto-reactivity and tissue pathology during this time frame, regardless of the precise mechanisms of contribution to the disease.

Our analysis of neutrophil contacts in the spleen reveals that neutrophils are preferentially localized near T cells early in disease, with a shift toward predominant B cell interactions with advanced disease. These data, in conjunction with the results of neutrophil depletion, suggest that neutrophils play a protective role via interaction with splenic T cells. Prior studies have investigated the effects of splenic neutrophils on lymphocyte proliferation and effector function in vitro but with apparently conflicting results. Thus, Trigunaite et al. reported that NZB/W splenic Gr-1highCD11b+ cells suppressed B cell differentiation to antibody secreting cells in vitro, suggesting that splenic neutrophils play a protective role and consistent with worsening disease upon in vivo anti-Gr-1 antibody administration in male mice. Interesting differences were noted in the mechanisms of suppression by neutrophils isolated from young male vs. female mice, with an ROS and NO dependence only in neutrophils from female mice. Similar to our study, a plasticity in neutrophil function was suggested by the loss of the suppressive phenotype in neutrophils from older mice (16). This same group also described Gr-1+ cell inhibition of Tfh differentiation in vitro and correspondingly increased Tfh with in vivo depletion of Gr-1+ cells, although the specificity of these findings to a neutrophil population is undetermined (46). In other studies, co-culture of neutrophils with T cells impaired Treg differentiation and promoted Th17 differentiation (17), leaving an open question as to whether neutrophils are predominantly immunosuppressive. Additionally, it is unclear to what extent these in vitro assays recapitulate neutrophil-lymphocyte interactions in vivo. In particular, the results of in vitro culture of neutrophils are confounded by the fact that neutrophils are easily activated when isolated and cultured ex vivo, and thus neutrophil respiratory burst or neutrophil cell death in vitro may underlie the observed suppression of splenic lymphocyte proliferation. Our results significantly add to the literature by providing the first in vivo evidence for a dominant inhibitory effect for neutrophils in lupus with significant increases in Tfh and GC B cells upon early neutrophil depletion. These data are compatible with neutrophil inhibition of Tfh differentiation, but it is also possible that inhibition of B cell differentiation plays a role given the contacts between neutrophils and B cells throughout the disease course.

Our results highlight that the influence of neutrophils on adaptive immune dysregulation depends on both the specific cell encounter and the phenotype of the neutrophil. This may have parallels in other chronic inflammatory conditions such as HIV infection, cancer, and hepatitis B, where neutrophils can adopt a granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell (gMDSC) phenotype (13) (38, 39). In addition to ROS production, neutrophils may acquire a suppressive phenotype via production of a wide variety of soluble and cell surface mediators (47–52). Our work expands the potential mechanisms by which neutrophils regulate adaptive immune responses in SLO, including TGFβ1, IL-1RA, and PD-L1. PD-L1 is particularly interesting in light of its association with a gMDSC phenotype and a recent report demonstrating significant elevation in PD-L1 expressing neutrophils in human SLE, correlating with disease activity (53). PD-L1 delivers inhibitory signals to activated T and B cells upon ligation of PD-1, and thus may provide a critical negative feedback mechanism to dampen autoimmune responses. Of note, Tfh express PD-1, and PD-L1-PD-1 interactions have been specifically shown to negatively regulate Tfh expansion (54). Further, blocking PD-L1 in the NZB/W lupus mouse model increased splenic PD-1+ T cells, anti-DNA levels, and nephritis (55). Based on our data, we hypothesize that PD-L1 expression by splenic neutrophils and inhibition of Tfh may be a key mechanism by which neutrophils suppress lupus disease development.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate the plasticity of neutrophil phenotype and function in terms of both transcriptional profile in SLO and changing spatial localization relative to B and T cells, dependent on the stage and severity of the disease. In turn, this neutrophil plasticity has dramatic effects on B cell autoimmunity, with surprisingly dominant regulatory effects as evidenced by the promotion of GC reactions and auto-reactive PC generation in the setting of neutrophil depletion. Despite the apparent complexity of neutrophil contributions to the outcome of autoimmunity, it is increasingly clear that neutrophils can exert a strong influence on adaptive immune dysregulation in lupus, highlighting the need for further investigation into the factors that may tip the balance in neutrophil acquisition of a pro-inflammatory versus regulatory phenotype.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the University of Rochester’s Flow Cytometry Core and Genomics Research Center for their technical expertise and helpful advice.

This work was supported by a CTSI pilot award (AKB), a Lupus Foundation of America LIFELINE Grant (JHA), and the Bertha and Louis Weinstein research fund (JHA). JHA has been supported by NIH grants P01-AI078907, R01-AI-077674, NIAMS Accelerated Medicines Partnership (1UH2AR067690),

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ahmed S, Anolik JH. B-cell biology and related therapies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatic diseases clinics of North America. 2010;36:109–130. viii–ix. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith CK, Kaplan MJ. The role of neutrophils in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Current opinion in rheumatology. 2015;27:448–453. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia-Romo GS, Caielli S, Vega B, Connolly J, Allantaz F, Xu Z, Punaro M, Baisch J, Guiducci C, Coffman RL, Barrat FJ, Banchereau J, Pascual V. Netting neutrophils are major inducers of type I IFN production in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:73ra20. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denny MF, Yalavarthi S, Zhao W, Thacker SG, Anderson M, Sandy AR, McCune WJ, Kaplan MJ. A distinct subset of proinflammatory neutrophils isolated from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus induces vascular damage and synthesizes type I IFNs. J Immunol. 2010;184:3284–3297. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pradhan VD, Badakere SS, Bichile LS, Almeida AF. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) in systemic lupus erythematosus: prevalence, clinical associations and correlation with other autoantibodies. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:533–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schnabel A, Csernok E, Isenberg DA, Mrowka C, Gross WL. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Prevalence, specificities, and clinical significance. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:633–637. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakkim A, Furnrohr BG, Amann K, Laube B, Abed UA, Brinkmann V, Herrmann M, Voll RE, Zychlinsky A. Impairment of neutrophil extracellular trap degradation is associated with lupus nephritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9813–9818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909927107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villanueva E, Yalavarthi S, Berthier CC, Hodgin JB, Khandpur R, Lin AM, Rubin CJ, Zhao W, Olsen SH, Klinker M, Shealy D, Denny MF, Plumas J, Chaperot L, Kretzler M, Bruce AT, Kaplan MJ. Netting neutrophils induce endothelial damage, infiltrate tissues, and expose immunostimulatory molecules in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2011;187:538–552. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmona-Rivera C, Zhao W, Yalavarthi S, Kaplan MJ. Neutrophil extracellular traps induce endothelial dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus through the activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1417–1424. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knight JS, Subramania V, O’Dell AA, Yalavarthi S, Zhao W, Smith CK, Hodgin JB, Thompson PR, Kaplan MJ. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition disrupts NET formation and protects against kidney, skin and vascular disease in lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:2199–2206. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ren Y, Tang J, Mok MY, Chan AW, Wu A, Lau CS. Increased apoptotic neutrophils and macrophages and impaired macrophage phagocytic clearance of apoptotic neutrophils in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2888–2897. doi: 10.1002/art.11237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knight JS, Zhao W, Luo W, Subramanian V, O’Dell AA, Yalavarthi S, Hodgin JB, Eitzman DT, Thompson PR, Kaplan MJ. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition is immunomodulatory and vasculoprotective in murine lupus. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2981–2993. doi: 10.1172/JCI67390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marvel D, Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment: expect the unexpected. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3356–3364. doi: 10.1172/JCI80005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janols H, Bergenfelz C, Allaoui R, Larsson AM, Ryden L, Bjornsson S, Janciauskiene S, Wullt M, Bredberg A, Leandersson K. A high frequency of MDSCs in sepsis patients, with the granulocytic subtype dominating in gram-positive cases. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;96:685–693. doi: 10.1189/jlb.5HI0214-074R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang X, Li J, Dorta-Estremera S, Di Domizio J, Anthony SM, Watowich SS, Popkin D, Liu Z, Brohawn P, Yao Y, Schluns KS, Lanier LL, Cao W. Neutrophils Regulate Humoral Autoimmunity by Restricting Interferon-gamma Production via the Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species. Cell Rep. 2015;12:1120–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trigunaite A, Khan A, Der E, Song A, Varikuti S, Jorgensen TN. Gr-1(high) CD11b+ cells suppress B cell differentiation and lupus-like disease in lupus-prone male mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2392–2402. doi: 10.1002/art.38048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji J, Xu J, Zhao S, Liu F, Qi J, Song Y, Ren J, Wang T, Dou H, Hou Y. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells contribute to systemic lupus erythaematosus by regulating differentiation of Th17 cells and Tregs. Clin Sci (Lond) 2016;130:1453–1467. doi: 10.1042/CS20160311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu H, Zhen Y, Ma Z, Li H, Yu J, Xu ZG, Wang XY, Yi H, Yang YG. Arginase-1-dependent promotion of TH17 differentiation and disease progression by MDSCs in systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:331ra340. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aae0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell AM, Kashgarian M, Shlomchik MJ. NADPH oxidase inhibits the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:157ra141. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palanichamy A, Bauer JW, Yalavarthi S, Meednu N, Barnard J, Owen T, Cistrone C, Bird A, Rabinovich A, Nevarez S, Knight JS, Dedrick R, Rosenberg A, Wei C, Rangel-Moreno J, Liesveld J, Sanz I, Baechler E, Kaplan MJ, Anolik JH. Neutrophil-mediated IFN activation in the bone marrow alters B cell development in human and murine systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2014;192:906–918. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson SW, Jacobs HM, Arkatkar T, Dam EM, Scharping NE, Kolhatkar NS, Hou B, Buckner JH, Rawlings DJ. B cell IFN-gamma receptor signaling promotes autoimmune germinal centers via cell-intrinsic induction of BCL-6. J Exp Med. 2016;213:733–750. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez P, Rodriguez-Carrio J, Caminal-Montero L, Mozo L, Suarez A. A pathogenic IFNalpha, BLyS and IL-17 axis in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus patients. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20651. doi: 10.1038/srep20651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bekar KW, Owen T, Dunn R, Ichikawa T, Wang W, Wang R, Barnard J, Brady S, Nevarez S, Goldman BI, Kehry M, Anolik JH. Prolonged effects of short-term anti-CD20 B cell depletion therapy in murine systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2443–2457. doi: 10.1002/art.27515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ichikawa HT, Conley T, Muchamuel T, Jiang J, Lee S, Owen T, Barnard J, Nevarez S, Goldman BI, Kirk CJ, Looney RJ, Anolik JH. Beneficial effect of novel proteasome inhibitors in murine lupus via dual inhibition of type I interferon and autoantibody-secreting cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:493–503. doi: 10.1002/art.33333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coquery CM, Loo W, Buszko M, Lannigan J, Erickson LD. Optimized protocol for the isolation of spleen-resident murine neutrophils. Cytometry A. 2012;81:806–814. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elbourne KB, Keisler D, McMurray RW. Differential effects of estrogen and prolactin on autoimmune disease in the NZB/NZW F1 mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 1998;7:420–427. doi: 10.1191/096120398678920352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vincent FB, Morand EF, Schneider P, Mackay F. The BAFF/APRIL system in SLE pathogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10:365–373. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu LJ, Yang X, Yu XQ. Anti-TNF-alpha therapies in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:465898. doi: 10.1155/2010/465898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vazquez MI, Catalan-Dibene J, Zlotnik A. B cells responses and cytokine production are regulated by their immune microenvironment. Cytokine. 2015;74:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panopoulos AD, Zhang L, Snow JW, Jones DM, Smith AM, El Kasmi KC, Liu F, Goldsmith MA, Link DC, Murray PJ, Watowich SS. STAT3 governs distinct pathways in emergency granulopoiesis and mature neutrophils. Blood. 2006;108:3682–3690. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-003012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Condamine T, Mastio J, Gabrilovich DI. Transcriptional regulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;98:913–922. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4RI0515-204R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vogl T, Eisenblatter M, Voller T, Zenker S, Hermann S, van Lent P, Faust A, Geyer C, Petersen B, Roebrock K, Schafers M, Bremer C, Roth J. Alarmin S100A8/S100A9 as a biomarker for molecular imaging of local inflammatory activity. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4593. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryckman C, Vandal K, Rouleau P, Talbot M, Tessier PA. Proinflammatory activities of S100: proteins S100A8, S100A9, and S100A8/A9 induce neutrophil chemotaxis and adhesion. J Immunol. 2003;170:3233–3242. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dessing MC, Tammaro A, Pulskens WP, Teske GJ, Butter LM, Claessen N, van Eijk M, van der Poll T, Vogl T, Roth J, Florquin S, Leemans JC. The calcium-binding protein complex S100A8/A9 has a crucial role in controlling macrophage-mediated renal repair following ischemia/reperfusion. Kidney international. 2015;87:85–94. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gasperini S, Marchi M, Calzetti F, Laudanna C, Vicentini L, Olsen H, Murphy M, Liao F, Farber J, Cassatella MA. Gene expression and production of the monokine induced by IFN-gamma (MIG), IFN-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant (I-TAC), and IFN-gamma-inducible protein-10 (IP-10) chemokines by human neutrophils. J Immunol. 1999;162:4928–4937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurko J, Vida A, Glant TT, Scanzello CR, Katz RS, Nair A, Szekanecz Z, Mikecz K. Identification of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:281. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez PC, Ochoa AC. Arginine regulation by myeloid derived suppressor cells and tolerance in cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Immunol Rev. 2008;222:180–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cloke T, Munder M, Taylor G, Muller I, Kropf P. Characterization of a novel population of low-density granulocytes associated with disease severity in HIV-1 infection. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48939. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pallett LJ, Gill US, Quaglia A, Sinclair LV, Jover-Cobos M, Schurich A, Singh KP, Thomas N, Das A, Chen A, Fusai G, Bertoletti A, Cantrell DA, Kennedy PT, Davies NA, Haniffa M, Maini MK. Metabolic regulation of hepatitis B immunopathology by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Nat Med. 2015;21:591–600. doi: 10.1038/nm.3856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daley JM, Thomay AA, Connolly MD, Reichner JS, Albina JE. Use of Ly6G-specific monoclonal antibody to deplete neutrophils in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:64–70. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dunay IR, Fuchs A, Sibley LD. Inflammatory monocytes but not neutrophils are necessary to control infection with Toxoplasma gondii in mice. Infect Immun. 2010;78:1564–1570. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00472-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wojtasiak M, Pickett DL, Tate MD, Londrigan SL, Bedoui S, Brooks AG, Reading PC. Depletion of Gr-1+, but not Ly6G+, immune cells exacerbates virus replication and disease in an intranasal model of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:2158–2166. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.021915-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scapini P, Nardelli B, Nadali G, Calzetti F, Pizzolo G, Montecucco C, Cassatella MA. G-CSF-stimulated neutrophils are a prominent source of functional BLyS. J Exp Med. 2003;197:297–302. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coquery CM, Wade NS, Loo WM, Kinchen JM, Cox KM, Jiang C, Tung KS, Erickson LD. Neutrophils contribute to excess serum BAFF levels and promote CD4+ T cell and B cell responses in lupus-prone mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schauer C, Janko C, Munoz LE, Zhao Y, Kienhofer D, Frey B, Lell M, Manger B, Rech J, Naschberger E, Holmdahl R, Krenn V, Harrer T, Jeremic I, Bilyy R, Schett G, Hoffmann M, Herrmann M. Aggregated neutrophil extracellular traps limit inflammation by degrading cytokines and chemokines. Nat Med. 2014;20:511–517. doi: 10.1038/nm.3547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Der E, Dimo J, Trigunaite A, Jones J, Jorgensen TN. Gr1+ cells suppress T-dependent antibody responses in (NZB x NZW)F1 male mice through inhibition of T follicular helper cells and germinal center formation. J Immunol. 2014;192:1570–1576. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duffy D, Perrin H, Abadie V, Benhabiles N, Boissonnas A, Liard C, Descours B, Reboulleau D, Bonduelle O, Verrier B, Van Rooijen N, Combadiere C, Combadiere B. Neutrophils transport antigen from the dermis to the bone marrow, initiating a source of memory CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2012;37:917–929. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beauvillain C, Delneste Y, Scotet M, Peres A, Gascan H, Guermonprez P, Barnaba V, Jeannin P. Neutrophils efficiently cross-prime naive T cells in vivo. Blood. 2007;110:2965–2973. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-063826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Megiovanni AM, Sanchez F, Robledo-Sarmiento M, Morel C, Gluckman JC, Boudaly S. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils deliver activation signals and antigenic molecules to dendritic cells: a new link between leukocytes upstream of T lymphocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:977–988. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0905526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maletto BA, Ropolo AS, Alignani DO, Liscovsky MV, Ranocchia RP, Moron VG, Pistoresi-Palencia MC. Presence of neutrophil-bearing antigen in lymphoid organs of immune mice. Blood. 2006;108:3094–3102. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abi Abdallah DS, Egan CE, Butcher BA, Denkers EY. Mouse neutrophils are professional antigen-presenting cells programmed to instruct Th1 and Th17 T-cell differentiation. Int Immunol. 2011;23:317–326. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxr007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang D, de la Rosa G, Tewary P, Oppenheim JJ. Alarmins link neutrophils and dendritic cells. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:531–537. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luo Q, Huang Z, Ye J, Deng Y, Fang L, Li X, Guo Y, Jiang H, Ju B, Huang Q, Li J. PD-L1-expressing neutrophils as a novel indicator to assess disease activity and severity of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis research & therapy. 2016;18:47. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-0942-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hams E, McCarron MJ, Amu S, Yagita H, Azuma M, Chen L, Fallon PG. Blockade of B7-H1 (programmed death ligand 1) enhances humoral immunity by positively regulating the generation of T follicular helper cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:5648–5655. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kasagi S, Kawano S, Okazaki T, Honjo T, Morinobu A, Hatachi S, Shimatani K, Tanaka Y, Minato N, Kumagai S. Anti-programmed cell death 1 antibody reduces CD4+PD-1+ T cells and relieves the lupus-like nephritis of NZB/W F1 mice. J Immunol. 2010;184:2337–2347. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.