Abstract

Understanding the molecular basis of mosquito behavioural complexity plays a central role in designing novel molecular tools to fight against their vector-borne diseases. Although the olfactory system plays an important role in guiding and managing many behavioural responses including feeding and mating, but the sex-specific regulation of olfactory responses remain poorly investigated. From our ongoing transcriptomic data annotation of olfactory tissue of blood fed adult female An. culicifacies mosquitoes; we have identified a 383 bp long unique transcript encoding a Drosophila homolog of the quick-to-court protein. Previously this was shown to regulate courtship behaviour in adult male Drosophila. A comprehensive in silico analysis of the quick-to-court (qtc) gene of An. culicifacies (Ac-qtc) predicts a 1536 bp single copy gene encoding 511 amino acid protein, having a high degree of conservation with other insect homologs. The age-dependent increased expression of putative Ac-qtc correlated with the maturation of the olfactory system, necessary to meet the sex-specific conflicting demand of mating (mate finding) versus host-seeking behavioural responses. Sixteen to eighteen hours of starvation did not alter Ac-qtc expression in both sexes, however, blood feeding significantly modulated its response in the adult female mosquitoes, confirming that it may not be involved in sugar feeding associated behavioural regulation. Finally, a dual behavioural and molecular assay indicated that natural dysregulation of Ac-qtc in the late evening might promote the mating events for successful insemination. We hypothesize that Ac-qtc may play a unique role to regulate the sex-specific conflicting demand of mosquito courtship behaviour versus blood feeding behaviour in the adult female mosquitoes. Further elucidation of this molecular mechanism may provide further information to evaluate Ac-qtc as a key molecular target for mosquito-borne disease management.

Keywords: Ecology, Evolution, Genetics, Zoology

1. Introduction

Mosquitoes are the vectors for many deadly infectious diseases including malaria, dengue, chikungunya, zika fever and yellow fever claiming a few hundred million lives annually. An adult female mosquito transmits the pathogens from an infected vertebrate host to a healthy host during a blood meal. The control of mosquito-borne diseases is still dependent on the use of chemical insecticides to suppress mosquito population or to interrupt mosquito-human interaction. However, the rapid emergence of insecticide resistance poses a challenge to control vector populations effectively. An alternative to overcome this challenge includes designing molecular tools to interfere the complex feeding and mating behavioural properties [1]. Compared to the vast research concentrated on female mosquitoes, male mosquito biology is rather less explored possibly due to its indirect influence on parasite transmission. Males induce several post-mating behavioural changes in females, which also includes the blood feeding behaviour. Thus, male mosquitoes maintain the unbroken chains of the mosquito life cycle and significantly contribute in transmitting diseases in an indirect way. In nature, both males and females feed on nectar sugar for their regular metabolic energy source. Only adult female mosquitoes take blood meal to fulfil the requirement of extra nutrients for their egg maturation. However the molecular basis of evolution and adaptation of dual feeding behaviour i.e. nectar sugar versus blood meal in adult female mosquitoes is not fully understood [2, 3]. Likewise, demystifying the process through which mosquitoes manage complex mating behavioural events i.e. swarm formation, suitable mate finding and successful aerial coupling is yet a major challenge to entomologists [4, 5, 6, 7]. A few molecular markers linked to mating behaviour have been characterized in Drosophila melanogaster [8, 9, 10]. But, the unavailability of any molecular marker regulating the complex mating behaviour in mosquitoes restricted our understanding.

Previous studies have indicated that neuro-olfactory system of mosquitoes regulates many complex behavioural responses such as mating, host seeking and blood feeding [11, 12, 13, 14]. Current evidence indicates that both male and female mosquito’s olfactory system encodes a fairly similar number of proteins [15, 16], but how sex-specific olfactory proteins manage the conflicting demand of feeding and/or mating behaviour is not known. Modest changes occurring in the olfactory repertoire in response to blood feeding in adult female mosquitoes have been reported by various groups [17, 18]. Therefore, we hypothesize that regulation of some of the sex-specific unique genes may facilitate and manage similar functions e.g. mate partner location by adult male/female mosquitoes or host finding for blood feeding by adult female mosquitoes.

An. culicifacies is one of the major rural vectors in India accounting for more than 65% of malaria cases. Control of this mosquito species has become worse due to the rapid emergence of multiple insecticide resistance [19]. In an effort to understand the complex feeding behaviour of adult An. culicifacies female mosquito [3], we have identified a unique transcript from the olfactory system of the blood-fed mosquito, encoding the ‘quick-to-court’ (qtc) protein. An. culicifacies qtc protein is a homolog of Drosophila coiled-coil qtc (Q9VMU5) protein and shown to play an important role in driving the male courtship behaviour. In D. melanogaster, it is predominantly expresses in olfactory organs, central nervous system and male reproductive tract [20, 21]. Mutations in the Dm-qtc not only caused the males to show elevated levels of male-male courtship, but also favoured abnormally quick courtship when placed in the presence of a virgin female [18]. Recently, a qtc homolog has also been identified from whole body transcriptome of the insect Bactrocera dorsalis [22, 23] but yet its function is yet to be characterized.

A significant modulation of this unique transcript, Ac-qtc in the olfactory tissue (∼5 fold up-regulation) in response to blood feeding prompted us to investigate its possible role in managing sex-specific conflicting demands of ‘mate choice’ and/or ‘food choice’ in the mosquito An. culicifacies. A comprehensive in silico function prediction analysis and extensive transcriptional profiling established a possible correlation that Ac-qtc might play a crucial role in the regulation and coordination of mosquito sex-specific behaviours.

2. Materials and methods

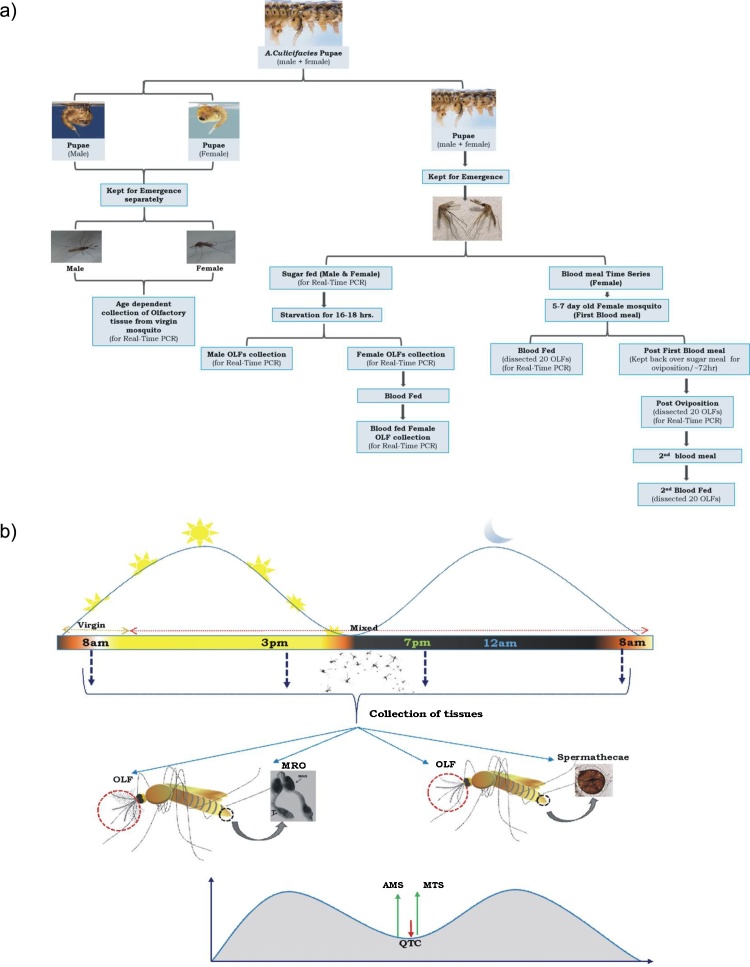

Fig. 1a represents a technical overview and workflow of the experiments to demonstrate the possible sex-specific role of Ac-qtc in adult An. culicifacies.

Fig. 1.

Technical designing and experimental work flow: (a) Experimental overview to demonstrate the possible role of Ac-qtc in mosquito behavioural regulation; (b) Pictorial presentation of the assay designed to correlate the function of Ac-qtc in the mating success of A.culicifacies mosquito. OLF: Olfactory; MRO: Male reproductive organ.

2.1. Mosquito rearing and maintenance

The cyclic colony of An. culicifacies, sibling species A was reared and maintained in standard laboratory conditions at 28 ± 2 °C and 80% relative humidity in central insectary facility as mentioned previously [3, 24]. All protocols for rearing and maintenance of the mosquito culture were approved by ethical committee of the institute.

2.2. Tissue collection and RNA extraction

From the ice anesthesized adult male and female An. culicifacies mosquitoes various tissues were collected. This included olfactory tissues (including antennae, maxillary palp, proboscis and labium), brain, reproductive tissues (male reproductive organ includes testes and male accessory gland; female reproductive organ consists of spermathecae and autrium) and legs. The tissues were dissected and collected in trizol. The developmental stages of An. culicifacies viz. egg, larvae (stages I − IV) and pupae were also collected in trizol after removal of extra water through filter paper. Total RNA was isolated by the standard trizol method as described previously [3, 25].

2.3. Bioinformatic analysis

The putative Ac-qtc was identified as a partial cDNA from olfactory tissue cDNA library sequence database of the blood fed adult female mosquito (unpublished). Multiple BLAST analysis against mosquito draft genome and other transcript database were done using open source analysis tools available at www.vectorbase.org. Domain prediction, multiple sequence alignment, and phylogenetic analysis were done using multiple softwares as described earlier [25].

2.4. Behavioural and molecular assay

To track the possible role of Ac-qtc in mating behaviour, an assay was designed (Fig. 1b) favouring sex-specific changes of the behavioural activities occurring in response to day/night cycle in the 5–6 days old mosquitoes. As per assay design, we collected olfactory and reproductive tissues from either virgin and/or mixed cage mosquitoes of both the sexes. For the assurance of mating success, we mixed an equal number of male and female virgin mosquitoes in a single cage at early morning (0800 h) and collected tissues at 1500 h, 1900 h, and overnight/0800 h next morning from the same cage. To test and validate the completion of insemination process, we profiled and compared the expression of two independent sperm-specific transcripts in the spermathecae of adult female mosquitoes. Previously characterized sperm-specific genes (AMS/FJ869235.1and MTS/FJ869236.1) of the mosquito An. gambiae [26] were queried to search and select sperm-specific homologs from the draft genome database of the mosquito An. culicifacies. The identified Ac-ams (ACUA010089) and Ac-mts (ACUA014389) transcripts sequences were used to design RT-PCR primers (See supplemental data for gene and primer sequence).

2.5. cDNA preparation and gene expression analysis

1 μg of total RNA was used to synthesize the first strand cDNA using Verso cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific) as described in the manufacturer protocol. Routine differential gene expression analysis was performed by the RT-PCR. Relative gene expression analysis was done using SYBR green qPCR (Thermo Scientific) master mix and Illumina Eco Real-Time PCR machine. The four step PCR cycle included an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, 40 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C, 15 s at 52 °C, and 22 s at 72 °C. Fluorescence reading was recorded at 72 °C after each cycle. In final steps, PCR at 95 °C for 15 sec followed by 55 °C for 15 sec and again 95 °C for 15 sec were completed before driving a melting curve. Reproducibility of the result was ensured by repeating the experiments with three independent biological replicates. Throughout the experiment, actin gene was used as an internal control and the relative quantification data were analyzed by 2–ΔΔCt method [27]. Statistical analysis of differential gene expression was done using Student’s t-test.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Identification, annotation and molecular characterization of Ac-qtc

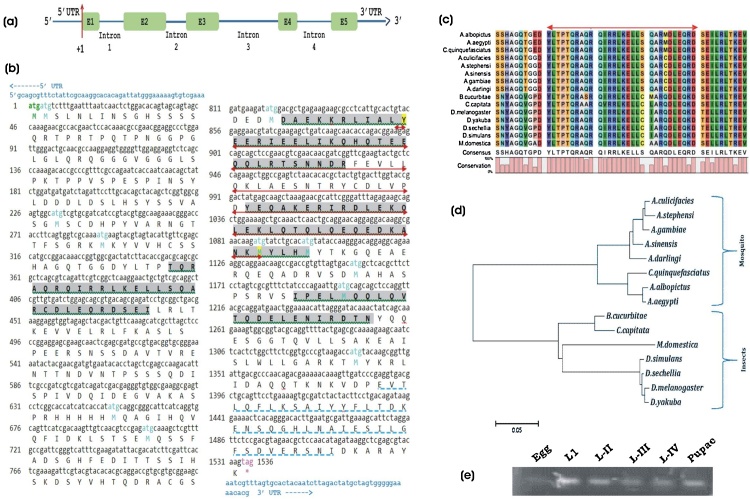

To identify the differentially expressed genes in naïve sugar fed vs. blood fed olfactory system (OLF) of An. culicifacies mosquito, currently we are annotating large-scale RNA-Seq transcriptomic databases (unpublished). During this annotation, we identified a unique transcript from blood fed olfactory transcriptome encoding Drosophila homolog of quick-to-court (qtc) protein, which plays a crucial role in many aspects of male mating behaviour. BLASTX analysis of the partial 383 bp long transcript showed 59% identity with the qtc homolog of Drosophila melanogaster, but no putative conserved domain was identified. To retrieve full-length An. culicifacies qtc transcript, we performed BLASTN analysis against An. culicifacies genome and transcript databases using the partial transcript as a query sequence. Comparative alignment analysis of the partial and full-length transcript indicated that the identified 383 bp putative Ac-qtc transcript lacks both 5′ and 3′ sequences. The detail in silico analysis of 1536 bp long full-length qtc transcript (ACUA027268) encoding a 511 amino acid long protein showed coiled-coil domain signature at the 3′ end of the sequence. Ac-qtc is a single copy gene, comprised of a 50 bp 5′ UTR region followed by five exons and four introns followed by a 50 bp 3′UTR region as shown in Fig. 2a. A comprehensive primary structural analysis of this full-length transcript (ACUA027268) revealed that it has four coiled-coils features and one conserved GRIP domain at the 3′ end of the sequence (Fig. 2b; Table 1). Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis revealed a high degree of sequence conservation within the mosquito and other insect species (Fig. 2c). RT-PCR analysis indicated that Ac-qtc was constitutively expressed in all the aquatic stages of development, except in the egg of the mosquitoes (Fig. 2d). This suggested that the quick-to-court protein is evolutionary conserved with the common function in the regulation of insects behavioural responses.

Fig. 2.

Genomic and molecular characterization of An. culicifacies quick-to-court gene: (a) Schematic representation of the genomic architecture of the mosquito Ac-qtc. Five green coloured boxes (E1-E5) indicates the exons and +1 mark the transcription initiation site. (b) Gene organization and molecular features of full length Ac-qtc: The gene contains 1536 bp nucleotide, encoding 511 AA long peptides with four coiled-coils domains. Both 5′ and 3′-UTR regions are highlighted (Light blue) letters. The complete coding region of 511 amino acids starts from ATG/Methionine/green colour, ending with TAG/Red/*. The different features are highlighted with different colour code, viz. Coiled-coil domains (grey colour and green underlined), Pre-folding domain (Red arrow) and GRIP-domain (sky blue dotted line). (c) Multiple sequence alignment of selected coiled coil domain (marked with green arrow) and (d) phylogenetic relationship of Ac-qtc with other mosquito species and Drosophila (e) Developmental expression of Ac-qtc in An. culicifacies by RT-PCR.

Table 1.

Molecular features of predicted domain in the mosquito Ac-qtc gene.

| SI. No. | Feature Type | Start Site | End Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Coiled-coils (Ncoils) | 118 | 146 |

| 2. | Coiled-coils (Ncoils) | 275 | 310 |

| 3. | Coiled-coils (Ncoils) | 332 | 367 |

| 4. | Coiled-coils (Ncoils) | 396 | 417 |

| 5. | Prefolding Domain | 285 | 363 |

| 6. | GRIP domain | 463 | 504 |

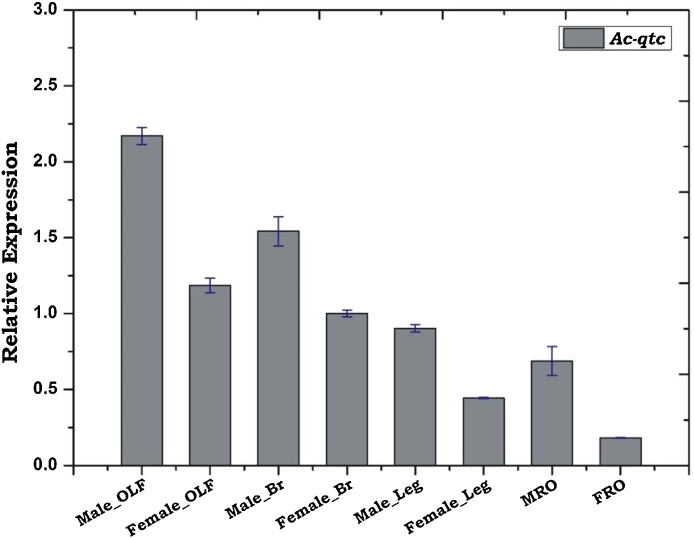

3.2. Ac-qtc abundantly expresses in the olfactory and brain tissues of adult mosquitoes

Sex and tissue-specific transcriptional profiling of Ac-qtc in the naive mosquitoes revealed the qtc gene expression in the olfactory tissue, brain and reproductive organs of both the sexes (Fig. 3). The previous study in D. melanogaster also demonstrates that Dm-qtc is expressed in the olfactory organs, central nervous system of both the sexes and male reproductive tract [18]. Interestingly, a relatively higher abundance of qtc gene in the olfactory tissue of male An. culicifacies indicated its possible involvement in the regulation of mosquito mating behaviour.

Fig. 3.

Tissue and sex specific relative expression analysis of Ac-qtc in the adult mosquito. Male OLF: Male olfactory tissue (Antennae, maxillary palp and proboscis); Female OLF: female olfactory tissue; Male-Br: Male brain; Female-Br: female brain; Male-leg; Female-leg; MRO: Male reproductive organ; FRO: Female reproductive organ.

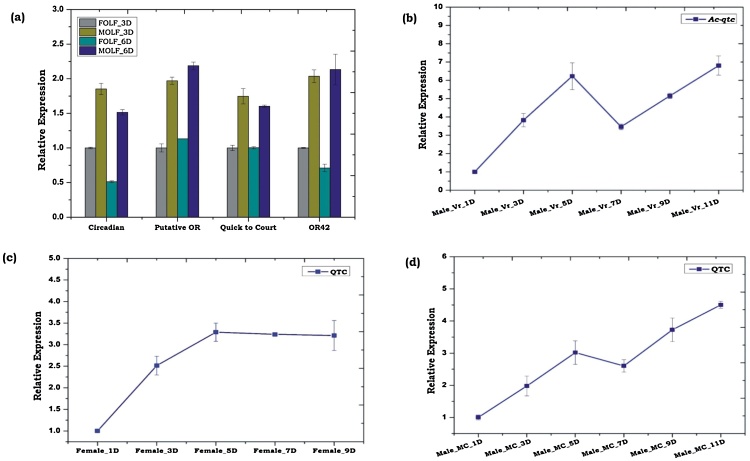

3.3. The sex-specific and age-dependent expression may regulate olfactory system maturation

Unlike Drosophila, unavailability of the proper molecular marker restricted our understanding of the complex mating biology in mosquitoes. In particular, studies on An. culicifacies mating behaviour are too limited [28]. However, our identification of the quick-to-court transcript from the blood fed olfactory tissue transcriptome data depicts that Ac-qtc may regulate the key molecular factors driving sex-specific behavioural modulation in An. culicifacies.

To test this hypothesis, we first examined the sex-specific relative expression of a pool of four transcripts including qtc, that were identified from the ongoing olfactory tissue transcriptomic study of blood fed adult female mosquito (Fig. 4a). Our data indicated that male olfactory system matures faster than female olfactory system even if they are at the same age. Next, we monitored the age-dependent transcriptional regulation of Ac-qtc in virgin male and female mosquitoes. Irrespective of the mosquito sexes, it showed age-dependent enrichment of Ac-qtc at the highest level (∼6- fold up-regulated/p ≤ 0.004) on the 5th day, when compared to 1-day old virgin mosquitoes (Fig. 4b, c), followed by at least 2-fold down-regulation (p ≤ 0.0172) on the 7th day. Interestingly after 7th-day Ac-qtc expression switched to up-regulation in male mosquitoes but it remained constant after 5th day in case of female mosquitoes. A similar pattern of Ac-qtc gene expression was also observed in the possibly mated male mosquitoes (Fig. 4d), which were collected from a mixed cage containing an equal number of male and female mosquitoes.

Fig. 4.

Sex specific and age dependent transcriptional response of Ac-qtc transcripts in the olfactory tissue of An. culicifacies. (a) Expression analysis of four transcripts viz. circadian, putative olfactory receptor (putative OR), quick-to-court and olfactory receptor 42 (OR42); FOLF: Female Olfactory; MOLF: Male Olfactory; (b-c) Age dependent transcriptional profiling of Ac-qtc in the virgin male and female mosquitoes (c): Male-Vr-1D: Male virgin mosquito of 1 Day old; Female-Vr-1D: Female virgin mosquito of 1 Day old. (d) Age dependent relative expression analysis of Ac-qtc transcript in the mated mosquito. Male-MC-1D: Male mosquito of 1 day old, collected from mixed cage (MC) containing equal number of male and female mosquitoes.

Although, it is yet unclear that how environmental guided non-genetic and/or genetic factors regulate the complex sexual behavioural events. But, our observations indicated that once male mosquitoes achieved the specific age of adulteration, the natural dysregulation of Ac-qtc by unknown mechanism may promote the courtship behaviour (see next paragraph). These results also corroborate with the previous findings in Drosophila where a mutation in Dm-qtc gene causes accelerated male-male courtship behaviour [18]. A recent study by Houot et al. also suggested that the qtc and shaker genes, which are abundantly expressed in the neuro-olfactory system of Drosophila, decrease the ability to discriminate between the sex targets [28, 29, 30, 31]. This is probably due to the declined perception to wild type female pheromone [28, 29, 30, 31].

3.4. Natural dysregulation of Ac-qtc may promote mating success

An alternative interpretation, of the above argument, could be that a significant downregulation (p ≤ 0.0172) of Ac-qtc in the 5–7 day old virgin adult male mosquitoes may be crucial for the auto-activation of courtship behaviour in case of An. culicifacies mosquitoes. In the lack of any molecular marker for mating behaviour studies, we attempted to trace the possible functional correlation of male Ac-qtc in the mating success i.e. insemination event completion in the laboratory-reared mosquitoes. However, our initial experiments of Ac-qtc gene silencing using purified dsRNA injection in the thorax of male mosquito’s remains unsuccessful, primarily due to a high mortality rate of these mosquitoes (data not shown).

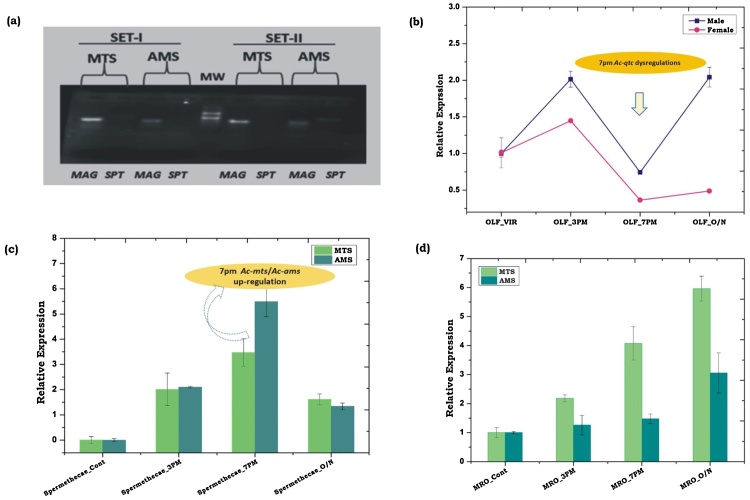

Available literature suggests that in most Anopheline mosquitoes, the mating behavioural activities commenced by the onset of sunset, usually at 1700 h which may continue till 2000 h [29, 32, 33]. We hypothesize that the transcriptional modulation of Ac-qtc in response to dawn/dusk cycle must have a functional correlation with the mating success, especially insemination events where adult females receive and store the sperms in their spermathecae delivered by the male during copulation [34, 35]. For experimental verification of this idea, we first identified two sperm-specific transcripts from the draft genome of An. culicifacies, using (ams and mts) as query sequences, previously characterized from An. gambiae [26]. To validate sperm specificity, the primers designed against Ac-ams (ACUA010089) and Ac-mts (ACUA014389) were tested by RT-PCR in the male accessory glands (MAG) and spermathecae (SPT) collected from laboratory reared 3–4 day old virgin male and female mosquitoes, respectively (Fig. 5a). A non-specific poor amplification was visible in case of Ac-ams in virgin female mosquito spermathecae. This was verified by incorrect melting curve signal that appeared in Real-Time PCR data (Supplemental Fig. S1). To trace the possible functional correlation of Ac-qtc in mating success, we collected olfactory and reproductive tissues two hours prior or later onset of the sunset as described in methodology section (See experimental design Fig. 1b). We then analysed and compared sex-specific regulation of Ac-qtc in the olfactory tissue, and sperm-specific Ac-ams/Ac-mts genes in the male and female reproductive organs.

Fig. 5.

(a) RT-PCR based expression validation of Ac-ams and Ac-mts in MAG (Male Accessory Gland) and SPT (Spermathecae). (b) Sex-specific transcriptional profiling of Ac-qtc at different circadian time in the olfactory tissues of the mosquito An. culicifacies; (c) Transcriptional response of Ac-mts and Ac-ams in the spermathecae of An. culicifacies at different circadian time. (d) Transcriptional response of Ac-mts and Ac-ams in male reproductive organ (MRO) at different circadian time. OLF: Olfactory; VIR: Virgin; Cont: Control; O/N: Overnight.

When compared to the virgin counterpart, significant down-regulation of Ac-qtc was observed in the olfactory system in both the sexes at 1900 h (Fig. 5b). This indicated that the lower expression of Ac-qtc may favour the increased mating frequency and active courtship engagement. A significant modulation of Ac-ams/Ac-mts expression in the mated female spermathecae (Fig. 5c) as well as male reproductive organs (Fig. 5d) supports the idea that a natural dysregulation of Ac-qtc in the late evening i.e. 1900 h may favour the copulation process by facilitating the release of unknown sex driving factors for successful insemination in the copulating couples. However, the exact molecular mechanism of qtc protein mediated regulation of insect’s mating events is still unknown.

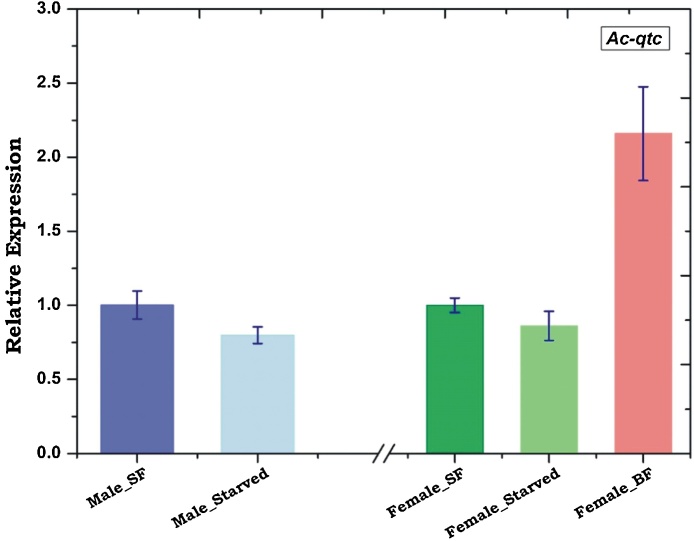

3.5. Ac-qtc regulation is independent of the nutritional status of the mosquitoes

Though feeding and mating are two mutually exclusive behavioural properties of any biological system. But those behaviours are dependent on each other to some extent at least for insects to facilitate the reproductive success and consequently their survival. The molecular basis of the sex-specific regulation of these conflicting behavioural demands (feeding vs. mating) remains largely unknown. Current studies in Drosophila suggested that food odour and sex-specific pheromone signals in the neuro-olfactory system work collaboratively to drive both the meal and/or mate attraction [31]. Thus to test whether Ac-qtc has any sex-specific relation to the nutritional status of naïve mosquitoes, we examined and compared the relative expression of Ac-qtc transcript in starved and sugar fed mosquitoes in both the sexes. To perform this experiment, we collected olfactory tissue from 5-6-day old sugar fed and 16–18 h starved mosquitoes. Relative gene expression analysis indicated that starvation did not affect the abundance of qtc transcript, but showed a two-fold up-regulation (p ≤ 0.03) in response to immediate i.e. 30 min − 1 h post blood feeding (Fig. 6). Together these data suggested that Ac-qtc may not be essential for regulating mosquito sugar feeding behaviour but it may have an important role in the regulation of host-seeking/blood feeding behaviour in the adult female mosquitoes.

Fig. 6.

Effect of starvation on Ac-qtc expression: both male and female mosquitoes were kept starved for 16–18 h and the olfactory tissues were collected for qtc expression study. Additionally blood meal was provided to female mosquitoes after starvation. SF: Sugar Fed; BF: Blood Fed.

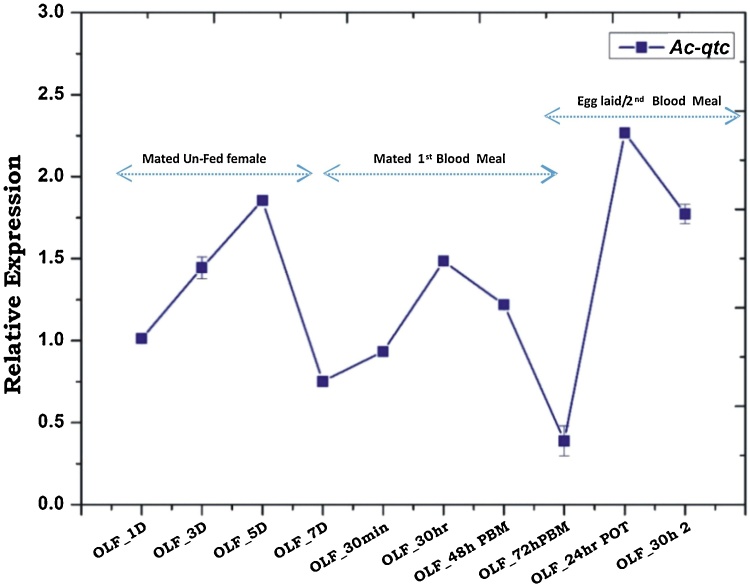

3.6. Blood meal alters expression of Ac-qtc in adult female mosquito

To further evaluate Ac-qtc role in response to blood feeding behaviour of female mosquitoes, we performed a blood meal time series experiment as described earlier [3]. We collected olfactory tissue from An. culicifacies mosquito depending on their age and blood feeding status. Ac-qtc expression analysis revealed increased abundance till 5th day, but significant (2.5 fold/p ≤ 0.03) downregulation on 7th day in the naive unfed adult female mosquitoes. This pattern is similar to the adult male mosquitoes (Fig. 7), which may probably to achieve the optimal courtship behavioural success in both the sexes.

Fig. 7.

Transcriptional behaviour of Ac-qtc in two consecutive blood meal follow up. OLF-1D − OLF-7D: Olfactory tissue from 1Day −7 Day old female; OLF–30 min: Olfactory tissue collected from 30 min post blood fed mosquito; OLF-30 h: Olfactory tissue collected from 30 h post blood fed mosquito; OLF-48 h: Olfactory tissue collected from 48 h of post blood fed mosquito; OLF-72 h: Olfactory tissue collected from 72 h post blood fed mosquito; OLF-24 h POT: Olfactory tissue collected from 24 h of post oviposition of mosquito; OLF-30 h 2: Olfactory tissue collected from 30 h of 2nd blood meal. PBM: Post Blood Meal.

Although it is not clear whether the first blood meal transiently and/or completely pauses re-mating events, but a consistent up-regulation of Ac-qtc just after blood feeding (within 30 min) till 30 h post blood meal (Fig. 7) indirectly suggested that adult female mosquito may not seek any courtship event at least for the first 30 h post blood meal. Furthermore, the continuous sharp downregulation (∼4 fold) of Ac-qtc till 72 h post first blood meal still remains questionable. It is unclear, whether Ac-qtc promotes host-seeking behaviour for second blood meal and/or it initiates mate partner finding. Significant up-regulation (∼1.3 fold; Fig. 7b) of Ac-qtc after oviposition and prior to second blood meal also support our hypothesis. Second blood meal again rapidly downregulated the Ac-qtc expression, when examined 30 h post blood fed in the olfactory tissue. Together these data indicate that Ac-qtc may have a unique role in driving dual mode of behavioural responses possibly to meet the conflicting demand of sexual mate partner and/or finding a suitable vertebrate host for blood feeding.

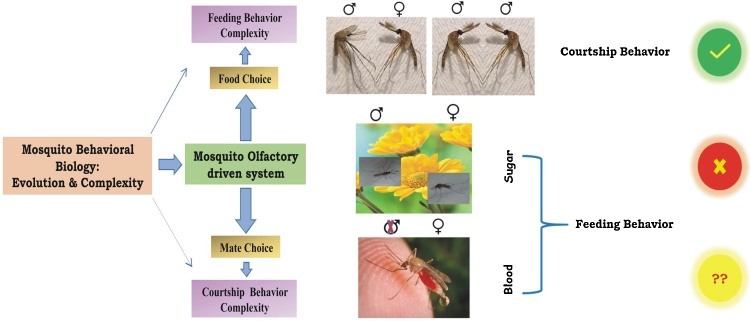

4. Conclusion

Understanding the sex-specific molecular genetics of mosquito’s behavioural biology is more complex. This is partly due to unique nature of blood feeding evolution and adaptation in the adult female mosquitoes, and limitation of generating mutants. Through comprehensive molecular approach, we examined the sex-specific transcriptional regulation of a unique transcript Ac-qtc, and predicted its possible role with ‘food choice’ and/or ‘mate choice’ behavioural performance (Fig. 8). Our data provides the first molecular evidence that Ac-qtc proteins may have a dual mode of action in the regulation of a cluster of mosquito olfactory genes that are linked to mating success and/or blood feeding in adult female mosquitoes. We believe these findings may guide to uncover the functional nature of Ac-qtc controlling complex mating and/or blood feeding behaviour in mosquitoes.

Fig. 8.

Proposed hypothesis for the possible function of quick-to-court gene in mosquito. Photo credit to James Gathany for the blood fed mosquito picture.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Tanwee Das De: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Punita Sharma, Charu Rawal, Seena Kumari, Sanjay Tavetiya, Jyoti Yadav: Performed the experiments.

Yasha Hasija: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Rajnikant Dixit: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Government of India (No.3/1/3/ICRMR-VFS/HRD/2/2016). Rajnikant Dixit is a recipient of a ICMR Visiting Fellowship. Tanwee Das De is recipient of UGC Research Fellowship (CSIR-UGC-JRF/20-06/2010/(i)EU-IV). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Data associated with this study has been deposited at Genbank under the accession number KX575650.

Acknowledgement

We thank insectary staff members of NIMR for mosquito rearing. We also thank Kunwarjeet Singh for technical assistance in the laboratory. Finally, we are thankful to Xcelris Genomics, Ahmedabad, India for generating NGS sequencing data.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Liu N. Insecticide Resistance in Mosquitoes: Impact, Mechanisms, and Research Directions. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2015;60:537–559. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pates H., Curtis C. Mosquito Behavior and Vector Control. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2005;50:53–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.50.071803.130439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma P., Sharma S., Maurya R.K., Thomas T., De T.D., Singh N., Pandey K.C., Valecha N., Dixit R. Unraveling dual feeding associated molecular complexity of salivary glands in the mosquito Anopheles culicifacies. Biol. Open. 2015;4(8):1002–1015. doi: 10.1242/bio.012294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibson G., Russell I. Flying in Tune: Sexual Recognition in Mosquitoes. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1311–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fawaz E.Y., Allan S.A., Bernier U.R., Obenauer P.J., Diclaro J.W. Swarming mechanisms in the yellow fever mosquito: aggregation pheromones are involved in the mating behaviour of Aedes aegypti. J. Vector Ecol. 2014;39:347–354. doi: 10.1111/jvec.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paton D., Touré M., Sacko A., Coulibaly M.B., Traoré S.F., Tripet F. Genetic and Environmental Factors Associated with Laboratory Rearing Affect Survival and Assortative Mating but Not Overall Mating Success in Anopheles gambiae Sensu Stricto. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howell P.I., Knols B.G.J. Male mating biology. Malar. J. 2009;8:1475–2875. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-S2-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carey A.F., Carlson J.R. Insect olfaction from model systems to disease control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:12987–12995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103472108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mackay T.F.C., Heinsohn S.L., Lyman R.F., Moehring A.J., Morgan T.J., Rollmann S.M. Genetics and genomics of Drosophila mating behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:6622–6629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501986102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demir E., Dickson B.J. fruitless Splicing Specifies Male Courtship Behavior in Drosophila. Cell. 2005;121:785–794. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rideout E.J., Dornan A.J., Neville M.C., Eadie S., Goodwin S.F. Control of sexual differentiation and behavior by the doublesex gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:458–466. doi: 10.1038/nn.2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saveer A.M., Kromann S.H., Birgersson G., Bengtsson M., Lindblom T., Balkenius A., Hansson B.S., Witzgall P., Becher P.G., Ignell R. Floral to green: mating switches moth olfactory coding and preference. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2012;279:2314–2322. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.2710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schymura D., Forstner M., Schultze A., Kröber T., Swevers L., Iatrou K., Krieger J. Antennal expression pattern of two olfactory receptors and an odorant binding protein implicated in host odor detection by the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2010;6:614–626. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6.614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biessmann H., Nguyen Q.K., Le D., Walter M.F. Microarray-based survey of a subset of putative olfactory genes in the mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Insect Mol. Biol. 2005;14:575–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2005.00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pitts R.J., Rinker D.C., Jones P.L., Rokas A., Zwiebel L.J. Transcriptome profiling of chemosensory appendages in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae reveals tissue- and sex-specific signatures of odor coding. BMC Genom. 2011;12:271. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rinker D.C., Pitts R.J., Zhou X., Suhb E., Rokas A., Zwiebel L.J. Blood meal-induced changes to antennal transcriptome profiles reveal shifts in odor sensitivities in Anopheles gambiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:8260–8265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302562110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthews B.J., McBride C.S., Gennarom M.D., Despon O., Vosshall L.B. Theneurotranscriptome of the Aedes aegypti mosquito. BMC Genom. 2016;17:32. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2239-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaines P., Tompkins L., Woodard C.T., Carlson J.R. quick-to-court, a Drosophila Mutant With Elevated Levels of Sexual Behavior, Is Defective in a Predicted Coiled-Coil Protein. Genetics. 2000;154:1627–1637. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.4.1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raghavendra K., Barik T.K., Sharma S.K., Das M.K., Dua V.K., Pandey A., Ojha V.P., Tiwari S.N., Ghosh S.K., Dash A.P. A note on the insecticide susceptibility status of principal malaria vector Anopheles culicifacies in four states of India. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2014;51:230–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winbush A., Reed D., Chang P.L., Nuzhdin S.V., Lyons L.C., Arbeitman M.N. Identification of Gene Expression Changes Associated With Long-Term Memory of Courtship Rejection in Drosophila Males. G3. 2012;2:1437–1445. doi: 10.1534/g3.112.004119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gomulski L.M., Dimopoulos G., Xi Z., Soares M.B., Bonaldo M.F., Malacrida A.R., Gasperi G. Gene discovery in an invasive tephritid model pest species, the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata. BMC Genom. 2008;9:243. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng W., Peng T., He W., Zhang H. High-Throughput Sequencing to Reveal Genes Involved in Reproduction and Development in Bactrocera dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae) PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas T., De T.D., Sharma P., Verma S., Rohilla S., Pandey K.C., Dixit R. Structural and functional prediction analysis of mosquito Ninjurin protein: Implication in the innate immune responses in Anopheles stephensi. Int. J. Mosq. Res. 2014;1:60–65. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dixit R., Rawat M., Kumar S., Pandey K.C., Adak T., Sharma A. Salivary gland transcriptome analysis in response to sugar feeding in malaria vector Anopheles stephensi. J. Insect Physiol. 2011;57:1399–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dixit R., Roy U., Patole M.S., Shouche Y.S. Molecular and phylogenetic analysis of a novel family of fibrinogen related proteins from mosquito Aedes albopictus cell line. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2008;32:382–386. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krzywinska E., Krzywinski J. Analysis of expression in the Anopheles gambiae developing testes reveals rapidly evolving lineage-specific genes in mosquitoes. BMC Genom. 2009;10:300. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahmood F., Reisen W.K. Anopheles culicifacies: effects of age on the male reproductive system and mating ability of virgin adult mosquitoes. Med. Vet. Entomol. 1994;8:31–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1994.tb00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sawadogo S.P., Diabaté A., Toé H.K., Sanon A., Lefevre T., Baldet T., Gilles J., Simard F., Gibson G., Sinkins S., Dabiré R.K. Effects of Age and Size on Anopheles gambiae s.s. Male Mosquito Mating Success. J. Med. Ento. Mol. 2013;50:285–293. doi: 10.1603/me12041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cook P.E., Sinkins S.P. Transcriptional profiling of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes for adult age estimation. Insect Mol. Biol. 2010;19:745–751. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2010.01034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Houot B., Fraichard S., Greenspan R.J., Ferveur J.F. Genes Involved in Sex Pheromone Discrimination in Drosophila melanogaster and Their Background-Dependent Effect. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charlwood J.D., Wilkes T.J. Studies on the age-composition of samples of Anopheles darlingi Root (Diptera: Culicidae) in Brazil. Bull. Entomol. Res. 1979;69:337–342. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawkes F., Young S., Gibson G. Modification of spontaneous activity patterns in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae s.s. when presented with host-associated stimuli. Physiol. Entomol. 2012;37:233–240. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Degner E.C., Harrington L.C. A mosquito sperm's journey from male ejaculate to egg: Mechanisms, molecules, and methods for exploration. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2016;3483:897–911. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lebreton S., Trona F., Echeverry F.B., Bilz F., Grabe V., Becher P.G., Carlsson M.A., Nässel D.R., Hansson B.S., Sachse S., Witzgall P. Feeding regulates sex pheromone attraction and courtship in Drosophila females. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:13132. doi: 10.1038/srep13132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.