Abstract

Providing palliative care in Indigenous communities is of growing international interest. This study describes and analyzes a unique journey mapping process undertaken in a First Nations community in rural Canada. The goal of this participatory action research was to improve quality and access to palliative care at home by better integrating First Nations’ health services and urban non-Indigenous health services. Four journey mapping workshops were conducted to create a care pathway which was implemented with 6 clients. Workshop data were analyzed for learnings and promising practices. A follow-up focus group, workshop, and health care provider surveys identified the perceived benefits as improved service integration, improved palliative care, relationship building, communication, and partnerships. It is concluded that journey mapping improves service integration and is a promising practice for other First Nations communities. The implications for creating new policy to support developing culturally appropriate palliative care programs and cross-jurisdictional integration between the federal and provincial health services are discussed. Future research is required using an Indigenous paradigm.

Keywords: Journey mapping, palliative care, participatory action research, Indigenous paradigm, service integration, policy

Background

Palliative care

Palliative care is an approach to health care aimed at preventing and alleviating suffering and improving quality of life for people living with life-limiting illness and their families.1,2 In the past decade, understandings of palliative care have shifted away from a focus on end-of-life and cancer care, to being appropriate beginning at the time of a life-limiting illness diagnosis.3,4 A palliative approach to care that is offered concurrently with treatment throughout the illness trajectory reduces suffering, improves quality of life, and increases the likelihood that people will die at home if that is the setting of their choice.5–12

A palliative approach to care integrates physical, psychological, social and spiritual aspects of care.2 Best practices in palliative home care provision include an interdisciplinary team approach and the integration of services across the care continuum to support people who are dying and their families.3

The need to develop palliative care in Canadian First Nations communities

In this research, a First Nations community refers to a community populated by Indigenous people. In Canada, use of the term Indigenous, which is inclusive of all the original inhabitants of Canada (Métis, Inuit, and First Nations), is now replacing the terms Aboriginal and First Nations. However, in this article, the term First Nations is used because that is how the study community self-identified during the research.

In Canada, the need to develop palliative care programs in First Nations communities is urgent because the First Nations population is aging with high rates of chronic disease.13,14 There are 617 First Nations communities in Canada, mostly located in rural and remote areas.15 First Nations communities hold an enormous amount of traditional knowledge and expertise in supporting individuals and families at the end of life.16 However, lack of access to local palliative care services and poor health services integration require that many First Nations community members travel to urban and regional centers to receive care in hospitals and long-term care homes.16–21

The Canadian federal government has jurisdictional responsibility for funding health services in First Nations communities, but federal home care services include neither funding for palliative care nor sufficient home care funding to provide care for community members with complex end-of-life needs. Provincially funded palliative care services rarely extend to First Nations communities and even when they do, they are not well integrated with local home and community care services. As a result, although First Nations people want the opportunity to die at home in their home communities,3,17,18 many die in urban and regional centers feeling lonely and isolated, separated from family, community, and culture.22–24 Creating local palliative care programs in First Nations communities would better respect the wishes, traditions, and culture of First Nations seniors and their families17,25,26 and could reduce health care costs by decreasing the number of unnecessary hospital admissions and emergency department visits.27

Developing palliative care programs for Indigenous people is of growing international interest. In 2010, the International Journal of Palliative Care published a special issue on Indigenous palliative care that contained research and case studies from Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand. A more recent Australian paper (2013) reviewed Aboriginal palliative care models in Australia and concluded that there is a need for culturally specific palliative care models which are culturally appropriate, locally accessible, and delivered in collaboration and partnership with Aboriginal controlled health services.28 This research thus contributes to an international knowledge base.

A public health approach: building capacity for community-based palliative care

Over the past 25 years, a public health (or health promoting) approach to palliative care has emerged.29–31 This approach encompasses a variety of social efforts by governments, organizations, and communities that aim to improve the well-being of individuals and families facing a life-limiting illness(es).32 The public health approach to palliative care provision moves away from the medical model of service delivery, where care is delivered within professional services.31,32 The focus is on community-based care provided by family and health care providers in the clients’ home rather than in institutions.33 This approach emphasizes community development and seeks to intentionally create constructive partnerships between formal and informal care at policy, research, and practice levels.34

Although formal palliative care services are currently lacking in their communities, First Nations people have long-standing cultural traditions and knowledge that can be built on to provide care in the community.23,26,35–37 A public health approach to palliative care is consistent with the goals of First Nations communities because it moves away from the medicalized and institution-based Western model of providing end-of-life care. Instead, dying is normalized as part of the natural cycle of life and palliative care focuses on increased service provision to allow clients to receive care in their home communities where end-of-life traditions and ceremonies can be embraced. Successful implementation of a public health approach requires building community capacity38 as described in this research.

Broader participatory action research context of the study

This study was nested within the “Improving End-of-Life Care in First Nations Communities” (EOLFN) project—a 5-year participatory action research (PAR) project where researchers partnered with 4 Canadian First Nations communities to develop local palliative care programs using a process of community capacity development. The overarching goal was to improve end-of-life care in these 4 communities, giving community members the choice to die at home. Consistent with the PAR methodology, the process of change was the focus of the project—the communities worked with the researchers to identify the problem, do something about it, evaluate that solution, and make changes as required.39,40 Change was created incrementally through an emergent process. The ongoing PAR cycle included each community identifying an issue related to palliative care program development, taking action to address it, and evaluating the experience and outcome.3,41 Thus, evaluation is embedded throughout the PAR process.

Overall EOLFN project outcomes included community-based palliative care programs and teams that were locally designed and controlled in 4 First Nations communities, a policy framework for health care decision makers, and a Workbook of research-informed strategies and resources to guide palliative care development in other First Nations.3,41,42 This article focuses on one strategy (journey mapping) that one partnering community (Naotkamegwanning First Nation) created, implemented, and evaluated during their program development process.

Through the EOLFN project, Naotkamegwanning worked with the EOLFN research team to implement a community capacity development model and build a local palliative care program.3 A community needs assessment identified that Naotkamegwanning community members wanted the choice to die at home but were unable to due to the lack of a local palliative care program and lack of service integration between federally funded health care services in the community and provincially funded health care services.43,44 A palliative care Leadership Team (composed of Elders, community members, and local health care providers) was established to guide local palliative care program development. Creating an integrated care pathway for community members in need of palliative care was a priority. In this research, a care pathway is defined as a diagram that “outlines the expected care for clients who would benefit by receiving palliative care, including the appropriate timeframes for different phases of palliative care.”3(p2) The focus is on providing clients “the best palliative care and most positive outcomes as they move between different health care providers and organizations.”3(p2)

Description and Analysis of Journey Mapping

Purpose

The purpose of this article is to present the journey mapping process undertaken in Naotkamegwanning to improve access to and integration of health services for clients who want to receive their palliative care at home. The aims are to describe and analyze the journey mapping process and outcomes. The questions guiding the study were as follows:

What learnings and promising practices emerged from journey mapping in Naotkamegwanning that can be used to inform palliative care development in other First Nations communities?

What are the perceived benefits of the journey mapping process?

Was the journey mapping process and the resultant care pathway perceived to improve quality, access, and integration of health services for palliative care clients?

Research methods

This research embraced an Indigenous paradigm as the theoretical perspective. An Indigenous paradigm emphasizes relational accountability and honors Indigenous worldviews.45–48 A 2-eyed seeing approach enabled the incorporation of both Indigenous and Western ways of knowing.49 A PAR methodology was adopted,39,40 and an instrumental case study design was employed.50 The overall PAR research project, and this embedded case study, were approved by the Research Ethics Board of Lakehead University (REB #020 10-11) and the Chief and Council of Naotkamegwanning First Nation. All participants in the case study provided informed consent.

Case description

The case description includes 2 parts. First, the First Nations community context is described. This is followed by a description of the journey mapping process that was implemented in Naotkamegwanning over 2 years.

Community description

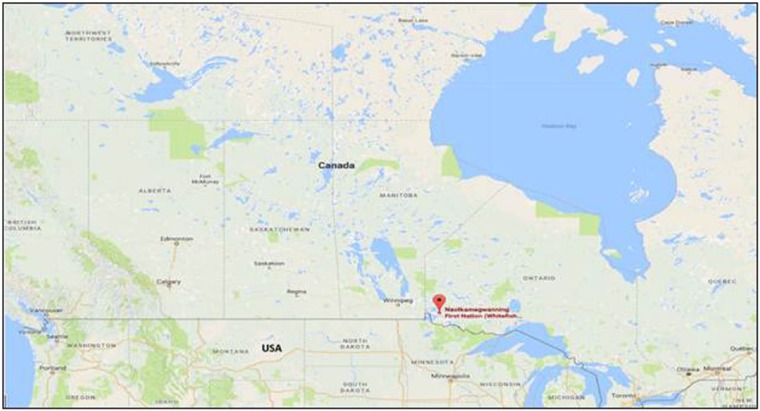

Naotkamegwanning First Nations is an Ojibway community located in Northwestern Ontario (rural Canada) in the Treaty 3 territory (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Naotkamegwanning First Nation (Whitefish Bay) area in Canadian Context (https://www.google.ca/maps/place/Naotkamegwanning+First+Nation+(Whitefish+Bay+First+Nation)/@49.4143563,-94.0863256,12.75z/data=!4m5!3m4!1s0x52bdced49415d4c5:0xd4d72b9a6706301f!8m2!3d49.4108329!4d-94.095833).

Approximately 712 people live in Naotkamegwanning, which has year-round road access. Naotkamegwanning community members take pride in keeping their cultural practices, beliefs, and traditions strong. Many people speak Ojibway and continue a connection with the land. The importance of passing on teachings, language, and cultural practices is evident in their delivery of programs and services within the community. In Naotkamegwanning, talking about death and dying is not culturally appropriate; instead, the community talks about Wiisokotaatiwin (“taking care of each other”). Thus, the community development work avoided the use of certain words (eg, death, dying, palliative, and end-of-life care)—the goal was to develop a culturally appropriate approach to service provision that supported very sick community members to remain at home to the end of life if that was their choice.

The nearest urban center (Kenora) has a population of approximately 15 348 and is 96 km to the north; this is the location where Naotkamegwanning community members access most of their health services. Specialty services are available in two larger urban centres: Thunder Bay, Ontario, approximately 460 km away, and Winnipeg Manitoba, approximately 290 km away (see Figure 2 for the community context in relation to Northwestern Ontario).

Figure 2.

Naotkamegwanning First Nation (Whitefish Bay) in the context of Northwestern Ontario (https://www.google.ca/maps/place/Naotkamegwanning+First+Nation+%28Whitefish+Bay+First+Nation%29/@49.2210023,-91.681051,8z/data=!4m2!3m1!1s0x52bdced49415d4c5:0xd4d72b9a6706301f).

Naotkamegwanning’s Community Care Program provides basic home and community care services in Naotkamegwanning. The program consists of services integrated at the local level that are funded by both the federal (nursing, personal support, and respite through the Home and Community Care Program) and provincial (home support and home maintenance through the Long Term Care Program) governments. The Community Care Program employs 8 staff and is funded to operate Monday to Friday, 8:30 am to 4:30 pm. The program provides services such as client assessment, home care nursing, homemaking, personal care and, respite, and provides medical equipment and supplies.44

The Community Care Program staff were drivers of change within the community to create a palliative care program with enhanced services. The Program Coordinator was the local lead for the EOLFN research and the Leadership Team. She applied for and received 10 months of pilot funding from the North West Local Health Integration Network for enhanced services to implement the care pathway following the journey mapping.

Description of journey mapping process

The process of journey mapping undertaken in Naotkamegwanning was inspired by the researchers’ knowledge of “customer journey mapping” and “value stream mapping” from the marketing and manufacturing industries, respectively. Journey maps help to understand customers’ interactions with company touchpoints and identify areas for improvement.51,52 Value stream mapping has evolved from a manufacturing-based model of flow53,54 to a health care quality improvement strategy. Value stream mapping is now commonly used to improve quality and efficiency of health services and better integrate services provided by different people or organizations by creating a visual map of the client experience.55,56 Many external health care providers who provided services in Naotkamegwanning, such as staff in home care agencies and hospitals, had already embraced value stream mapping in their organizations as a process of quality improvement.

In this research, the term journey mapping was adopted as it was more meaningful and acceptable to First Nations community participants. A facilitator external to the community was hired who was very experienced in value stream mapping in health care. However, it quickly became apparent that the usual terminology, facilitation style, and value stream mapping techniques were disempowering and not culturally appropriate for the First Nations participants. As a result, the workshop format was revamped to a story telling exchange, and the facilitator sat with the participants in a circle (rather than continuing to stand) through the process. This new format was more consistent with the guiding principles of the Indigenous paradigm,45 and it was well accepted by the external health care providers.

In collaboration with the Naotkamegwanning Leadership Team, the researchers implemented a series of 4 journey mapping workshops to design a palliative care pathway that would provide community members with the option to receive care at home in their community. These workshops brought together Elders, community leaders, and approximately 25 internal and external health care providers, all chosen by the community. The goals of the workshops included discussing the journey for Naotkamegwanning community members when they require palliative care (including discussions of the current and desired care pathways) and identifying areas for improving communication and service integration among health care and social service providers. Workshops were held in the First Nations community health center, in a hotel meeting room (Kenora), and the Kenora hospital. It was important for the locations to be accessible and comfortable for the First Nations and external health care provider participants. A key goal was relationship building during the workshops.

During the workshops, internal and external health care providers and the research team worked together to create a “desired” palliative care pathway for providing care for people who need palliative care at home in Naotkamegwanning. Workshops were highly interactive and engaged participants in identifying and drawing the steps in the care pathway on the wall, and then attaching notes to identify who was involved at each step and how, and the facilitators and barriers to care. Typical journey mapping workshop supplies included a large roll of paper, different color adhesive notepads, markers, and tape. Equipment included audio recorders, batteries, a laptop, and projector.

Through the workshops, barriers to service integration were identified related to lack of communication between health care providers, ineffective protocols for obtaining client consent to release information, insufficient discharge planning, and lack of cultural competence of external health care providers. In addition, strategies to overcome integration obstacles were developed or identified (eg, new consent forms, new discharge planning and care conferencing protocols in hospital, and cultural competency training). The aim and process of the 4 journey mapping workshops are summarized in Table 1 below. More workshop details are available elsewhere57 and in a journey mapping toolkit that can be found on the project website.58

Table 1.

Summary of Naotkamegwanning journey mapping workshops.

| Date | Length | Participants | Facilitator/format | Focus/results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Workshop 1 Introducing the journey mapping process and engaging stakeholders |

August 15, 2013 | ½ d (4 h) | n = 14 Community members, EOLFN research team, internal and external HCPs |

Principal investigator Face-to-face workshop |

Engagement and journey mapping (current state) Focused on bringing together community members, internal and external health care and service providers, and the research team for the first time Initial engagement of stakeholder partners Presented results of community needs assessment Announced the new palliative care program name: (Wiisokotaatiwin [taking care of each other]) Discussed “current” and “desired future” states of the client experience and how to move toward the desired future state. Group began to identify areas or improving communication and service integration among themselves that would improve the experience of the residents of Naotkamegwanning First Nation Established commitment from stakeholders to attend future journey mapping workshops and understanding that the goal of journey mapping was to create a palliative care pathway |

|

Workshop 2 Implemented and adapted value stream mapping using principles of Indigenous paradigm |

February 5-6, 2014 | 2 d (14 h) | n = 17 Community members, EOLFN research team, internal and external HCPs |

Outside consultant Face-to-face workshop |

Value stream mapping (began future state) Reunited existing stakeholders and introduced new stakeholders that were not present in Workshop 1, creating a more robust group of community members, internal and external health care and service providers, and research team members Consultant introduced “lean” concepts and value stream mapping Lean terminology was not culturally appropriate and was abandoned, shifted to an open discussion that embraced a 2-eyed seeing perspective Discussed in detail the gaps and barriers in establishing the palliative care pathway Identified communication breakdowns and strategies for improvement Mapped out the desired future state, resulting in a flowchart diagram of the various touchpoints involved in the desired future state of care pathway Created list of service providers involved in the future state Composed report and recommended next steps were provided to stakeholders |

|

Workshop 3 Finalizing the care path and next steps |

August 6, 2014 | ½ d (3 h) | n = 20 Community members, EOLFN research team, internal and external HCPs |

Principal investigator and community consultant Face-to-face workshop and webinar |

Journey mapping (future state/planning of details) Reunited the stakeholders and introduced the care path flowchart, discussed, and agreed on next steps Introduced the 9 stages in palliative care pathway (a linear care path diagram) for validation by stakeholders Worked through stages 1-5 building on what was identified in previous workshops Identified the outstanding gaps, barriers, and challenges in implementing the care pathway Of the 9 stages involved in the care path, the Leadership Team identified stages 6-9 as private to the community, thus they wanted to discuss the details of these stages only within the Leadership Team. The community informed the external partners that they would not be involved in stages 6-9 Created an action plan and agreed on next steps. It was determined that the next steps for the stakeholders would involve follow-up teleconferences to review a work plan to implement the care path |

|

Workshop 4 Including cultural components in the care path |

October 1-2, 2014 | 2 d (11 h) | n = 9 Project advisory committee and community members and EOLFN research team |

Community consultant Face-to-face workshop |

Validation of concepts from previous meetings; including cultural components and creation of care pathway This workshop was private to the community involving only members of the leadership and research teams (no external health care providers were present as the focus was on the internal community roles and activities) Review what had been done over the previous year with all of the stakeholders and ensure cultural components, beliefs, and traditions were incorporated into all of the stages of the care path The care pathway evolved from a linear process to a circular diagram identified as the 9-stage Wiisokotaatiwin Program care pathway A draft of stages 6-9 was created and documented during this workshop |

Abbreviations: HCPs, health care providers; EOLFN, Improving End-of-Life Care in First Nations Communities.

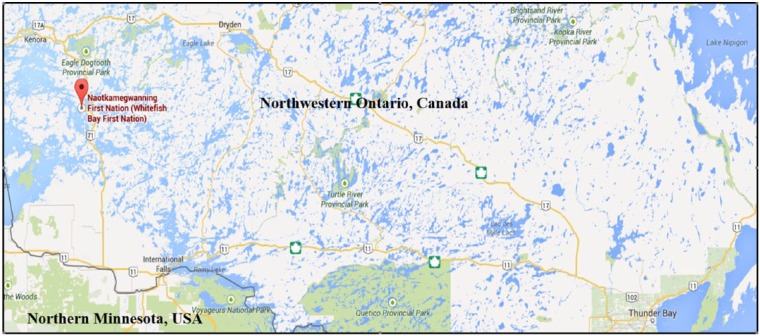

The outcome of these 4 workshops was the creation of a 9-stage palliative care pathway (Figure 3). This new care pathway integrated care within the community and between First Nations, regional, and district health services (see Table 2).

Figure 3.

The 9-stage Wiisokotaatiwin Program care pathway.59

Table 2.

First Nations and regional health services associated with the Wiisokotaatiwin Program care pathway.

| Naotkamegwanning Health Services (Naotkamegwanning) |

| ● Community Care Program (Program Coordinator, Home Care Nurse, Personal Support Workers, Home Maker, Home Support) ● First Nations Health Services (Administration, Health Clerk/Reception, Community Health Nurse, Community Health Educator, Mental Health Services, Elder Support Worker, Family Support Worker, Circle of Hope and Healing, Community Wellness Worker, Suicide Prevention/Black River Camp, Community Transportation Services) |

| District Health Services (Kenora) |

| ● Aboriginal Health Access Centre (Nurse Practitioner, Mental Health and Emotional Services) ● First Nations Health Authority (Psychologist, Social Worker, Mental Health Team, Spiritual Care providers) ● District hospital (Palliative Care Coordinator, Discharge Planner) ● District provincial home care agency (Physiotherapy, Occupational therapy, Social Work) ● Pharmacy (Medication and medical supplies) ● Health care equipment agency (home health care equipment) ● Funeral home |

| Regional Health Services (Thunder Bay) |

| ● Palliative Pain and Symptom Management Program (education, mentoring, and support for primary care health care providers providing palliative care) ● Telemedicine Nurse, Hospice Palliative Care Hospital Unit (pain and symptom management, palliative care clinical consultation) ● Telemedicine Program, Thunder Bay Regional Cancer Centre (access to telemedicine network for palliative care consultations) |

Consistent with the PAR methodology, the care pathway was then implemented through the community’s new palliative care program: the Wiisokotaatiwin Program. Six clients in need of palliative care were identified and enrolled in the Program.44 Care during the first 6 stages of the care pathway was provided in an integrated way between local (internal) and external health care providers. The last 3 stages of the care pathway were supported only by local health care providers to respect and protect cultural teachings about end of life.

Following implementation of the care pathway for 6 months, a fifth workshop was held to reflect on the experience to date and assess whether changes were required in the care pathway to improve client experience and service integration. Participants were those who attended the initial 4 workshops and who had been involved in implementing the care pathway with clients. Overall, the value of the care pathway was affirmed and some additional barriers to integration were identified, with plans made to overcome them (eg, need for translation services and need for increased physician involvement in care conferences). This final workshop is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of Naotkamegwanning First Nation Workshop 5.

| Date | Length | Participants | Facilitator/format | Focus/results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 7, 2016 (approximately 6 mo into the pilot implementation of the Wiisokotaatiwin Program) | 1 day | n = 11 Internal and external providers who had been involved in the development of the original care pathway and/or were key members of the clients’ care team and Leadership Team members |

EOLFN Consultant Face-to-face case study format: 3 clients’ stories were shared and then discussed using the following questions: were the care path steps followed, why or why not, were they effective, and what if any changes needed to be made to the care pathway? |

To assess implementation of the Wiisokotaatiwin Program Care Path ● Positive aspects of the care pathway were affirmed; areas where change was needed to make it more effective were identified and positive changes suggested ● The case study review revealed that the care path is, in general, effective, although there are specific areas where work needs to be done (eg, need translation services and schedule case conference when physician is in community) ● Recommendations and responsibilities to help alleviate the problems were identified |

Abbreviation: EOLFN, Improving End-of-Life Care in First Nations Communities.

Having described the journey mapping process (what was done), we turn now to the analysis of what was learned.

Analysis: process and outcome of journey mapping

Data collection

Throughout the PAR project, a mixed-methods approach was used to assess journey mapping implementation and outcomes. Detailed process data documented the planning and implementation of the workshops, and a focus group explored community members’ reflections on the experience. Following implementation of the care pathway, the perceived impact of the journey mapping to improve service integration was assessed through the fifth workshop (previously described) and surveys with internal and external health care providers.

Workshop data

Qualitative data in the form of researchers’ field notes, observations of the workshops, photos, workshop summary reports, and video recordings were collected during Workshops 1 to 4 (2013-2014). The facilitator of Workshop 5 (2016) prepared a written report summarizing the activities and outcomes of the workshop, including participants’ overall assessment of the care pathway.

Focus group

In April 2015, after the completion of the 4 journey mapping workshops, a focus group was conducted with Naotkamegwanning community members. Consistent with the principles of the Indigenous paradigm, the focus group was conducted using a sharing circle format. The focus group was guided by open-ended questions that were designed to explore the experience of community members in relation to these overarching questions: How effective was the journey mapping process to create the care pathway? What learnings and promising practices can be shared? Of the 8 community members invited, 7 participated in the focus group. Also, participating was the EOLFN Community Consultant who was hired to support and assist the Home and Community Care Program Coordinator (EOLFN Community Lead) in Naotkamegwanning (n = 8). The focus group was audio recorded and transcribed for analysis.

Survey

After the completion of the 4 journey mapping workshops, an online survey was conducted (between June and August 2015) with external health care providers (service providers who are external to the community but provide services in Naotkamegwanning, eg, hospital and home care providers) and members of the EOLFN Research Team. The survey combined a rating scale with 14 statements and 9 open-ended questions. The scale portion of the survey sought to document respondents’ perceptions of the journey mapping including the benefits for service integration related to communication, collaboration, and care delivery. The open-ended questions sought information related to the most and least beneficial aspects of the journey mapping workshops, what could have improved the workshops, and if participants would recommend similar workshops to other First Nations communities. Nine surveys were returned (56% response rate).

To decrease the data collection burden on the participants, increase First Nations participants’ cultural safety during the research process and because it was not essential to the study purpose, demographic data were not collected from focus group and survey participants. This is consistent with the PAR approach and the ethical principles guiding Indigenous health research. It is necessary to gather data that are meaningful to the participants in a way that is culturally safe for them. Indigenous health research ethics now prevent invasive or exploitive research as experienced by many Indigenous people in the past.

Data analysis

An incremental approach to data analysis was undertaken.

Focus group

To respect the Indigenous paradigm, the focus group data were analyzed first because these data best captured the voice of the community members related to the research questions. Generating the themes from the community perspective allowed for sensitization to the Naotkamegwanning participants’ perspective and provided a culturally respectful lens from which the journey mapping workshop data could be analyzed. A 3-part inductive analysis process was used which included line-by-line analysis of the transcript to identify the ideas represented during the focus group, grouping the ideas into themes and subthemes, and organizing the themes to address the research questions.60,61 The themes were displayed using a culturally appropriate visual diagram. The thematic diagram was refined several times to better reflect the data, more effectively address the research questions, and more clearly provide a structure to describe the journey mapping experience. An Elder was consulted for advice on how best to visually tell the story. Member checking was used to validate the themes and ensure that the voice of the community was accurately interpreted.62

Workshop data

Next, the journey mapping data were inventoried and organized by workshop sequence (1-4) and date. Within each electronic workshop folder were 3 categories: preparatory workshop documents, post workshop data (ie, meeting minutes, observations, field notes, and reports), and other data (ie, photographs and a video). The themes generated from the focus group analysis were used as a sensitizing framework to guide the analysis. An additional guide for analysis was created based on the research questions,63 and these questions were also used to examine the data (see Table 4). The written report summarizing Workshop 5 was also analyzed using the research questions as a guide.

Table 4.

Workshop data analysis guide.

| ● How effective was the journey mapping process to create the care pathway for integrated home palliative care? |

| ● What learnings and promising practices have emerged from this case study that can inform development for other First Nations communities? |

| ● What was the role or contribution of the various participants in the journey mapping process? |

| ● How did each stakeholder role contribute to the journey mapping process? |

| ● How did each of the 4 journey mapping workshops contribute to creating the care pathway? |

| ● What were the facilitators and barriers in the journey mapping process? |

| ● What were the key catalysts during the journey mapping workshops? |

| ● How did the workshops contribute to system integration? |

| ● How could the journey mapping process be improved in future? |

| ● What is the unfinished business in the journey mapping process? |

| ● What was the most significant change that resulted from the journey mapping and creation of the care pathway? |

| ● What process of palliative care journey mapping in First Nations communities is recommended for the future? |

| ● Was the concept of 2-eyed seeing evident in the data? If so, how? |

| ● Is there anything else in these data that is interesting, important, or relevant to the research questions? |

Survey

Finally, the survey data were transferred from SurveyMonkey into Microsoft Excel. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the quantitative data from the rating scale. The responses to the open-ended questions were analyzed line-by-line to capture participants’ opinions about the journey mapping experience. These qualitative data were then grouped, and 3 overarching themes were identified and summarized.

Results

The results of the analysis are organized by the questions that guided this case study.

What learnings and promising practices emerged from journey mapping in Naotkamegwanning that can inform palliative care development in other First Nations communities?

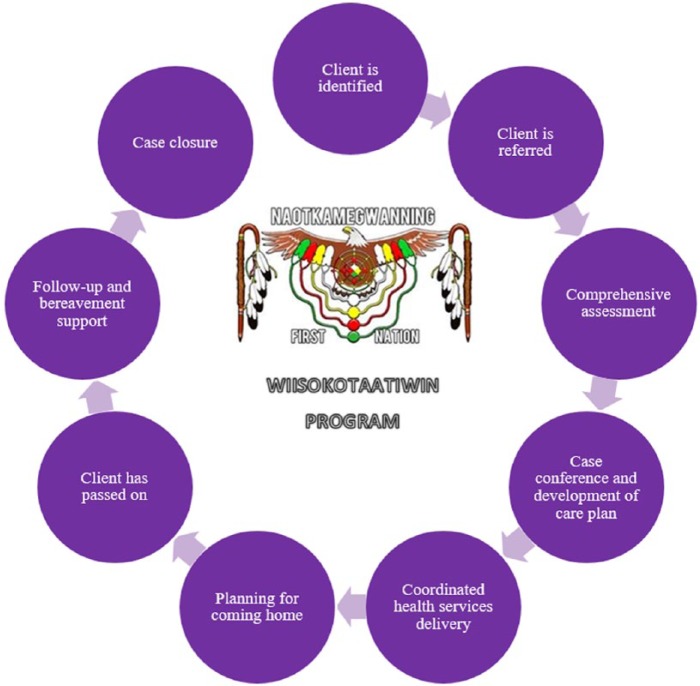

Focus group and workshop data findings

The results of the qualitative analysis of the focus group and journey mapping workshop data are represented in Figure 4 which incorporates an eagle perched atop a pine tree. This depiction emerged from a desire to communicate the findings visually and symbolically which is meaningful to Indigenous people who were the main intended audience. The eagle is an important symbol in Ojibway culture. Representation of the data within the body of an eagle is symbolic to the Naotkamegwanning First Nation community specifically as the eagle appears in the community logo. The journey mapping figure adopts the perched eagle as a grounding metaphor to infer that the journey mapping process must be founded in the community’s vision for change. The pine tree represents the EOLFN project’s overall approach based on the principles of PAR and the community capacity development model which guided the process of palliative care development.3

Figure 4.

Conducting effective palliative care journey mapping: learnings and promising practices.

As part of the member checking process, the figure was shared with key informant community members who verified that the figure is a thoughtful and appropriate representation of the findings. An Elder from outside of the community was also consulted, and he felt that the use of the eagle to represent the findings was appropriate and meaningful.

As shown in Figure 4, the qualitative data are grounded by the foundational theme “Journey mapping must be founded in the community’s vision for change.” Supporting the foundational theme and infusing up through the pine tree’s branches are the core ethical concepts of conducting journey mapping in First Nations communities: “building trusting relationships” and “honoring community control.” At the center of the eagle’s body is the core organizing concept, “Naotkamegwanning palliative care journey mapping.” A thematic map extending from the core out into the body identifies 4 major themes (closest to the center) and 5 subthemes that extend outward into the wingspan. These themes and subthemes are supported by direct quotes from the focus group participants or field notes and collectively represent the lessons learned and promising practices that emerged from the data. The learnings from the analysis of the process and focus group data are summarized in the following paragraph.

At the outset, journey mapping must be founded in the community’s vision for change. Journey mapping also requires community planning which involves ensuring the community’s readiness for journey mapping, and then obtaining community support, followed by creating awareness. Journey mapping is a time commitment that involves face-to-face meetings on a regular basis as well as stakeholder follow-through. Stakeholder commitment to journey mapping workshops and involvement in creation of the care pathway are essential. Communication should be respectful of the community’s beliefs, as death and dying are not discussed and palliative care is a Westernized concept, therefore not a familiar term in the Ojibway language. The value stream mapping approach, although familiar to the external service providers, did not resonate with community members. Journey mapping workshops should be in a format that is culturally relevant and familiar. Naotkamegwanning journey mapping was effective in creating a 9-stage, culturally appropriate care pathway, and Elder guidance is recommended throughout the journey mapping process. Health care providers and caregivers must tailor each client’s experience through the care pathway to their individual wishes, values, and beliefs.

Survey findings

Analysis of the open-ended survey questions resulted in the following 3 overarching themes:

Journey mapping was a time commitment.

Journey mapping increased communication and established partnership.

Journey mapping is recommended to create a care pathway.

One of those themes “Journey mapping was a time commitment” illustrates another learning that emerged about journey mapping. When asked what the barriers were during the journey mapping workshops, all respondents identified time as a barrier. Survey respondents expressed that journey mapping was a major time commitment, stating that the duration from start to finish was too lengthy, and the time between workshops (6 months) needed to be reduced. One of the most time-consuming components of the journey mapping workshops was working through each of the 9 stages in the care pathway. To work through the care pathway, health care providers and community members needed to understand one another’s policies and procedures to identify gaps and problems in service delivery. Despite being time-consuming, the responses to the rating scale indicated that as a result of the journey mapping workshops, health care providers reported that they better understood each other’s mandates, and that gaps and problems in service delivery were identified during the journey mapping workshops.

What are the perceived benefits of the journey mapping process?

Survey findings

Overall, there was a high level of agreement on most rating scale items among the survey respondents (see Table 5). The survey results indicate many perceived benefits related to service delivery, relationship building, and communication and partnerships.

Table 5.

Summary of rating scale findings (n = 9).

| Statement | Do not know | Disagreea | Agreeb |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Naotkamegwanning journey mapping workshops helped me look at my work in a different way than before | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| 11% | 11% | 78% | |

| The Naotkamegwanning journey mapping workshops helped me better understand the roles of the other care providers involved | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| 0% | 11% | 89% | |

| The Naotkamegwanning journey mapping workshops helped me better understand the policies and procedures (mandates) of the other organizations involved | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| 0% | 0% | 100% | |

| The Naotkamegwanning journey mapping workshops identified gaps and problems in service delivery | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| 0% | 0% | 100% | |

| The Naotkamegwanning journey mapping workshops identified new strategies to improve communication, coordination, and integration of care delivery | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| 0% | 11% | 89% | |

| The Naotkamegwanning journey mapping workshops helped me better understand the needs and preferences of clients in Naotkamegwanning | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| 0% | 11% | 89% | |

| The Naotkamegwanning journey mapping workshops generated commitment to solve service delivery issues for residents of Naotkamegwanning | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| 0% | 11% | 89% | |

| The Naotkamegwanning journey mapping workshops will help to improve care delivery for Naotkamegwanning residents who are in the last year of life | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| 11% | 11% | 78% | |

| I feel like my voice was heard in the Naotkamegwanning journey mapping workshops | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| 12.5% | 0% | 87.5% | |

| I feel like the voice of the community members was respected during the Naotkamegwanning journey mapping workshops | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| 0% | 0% | 100% | |

| I feel like the views of the community members were incorporated during the Naotkamegwanning journey mapping workshops | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| 0% | 0% | 100% | |

| I feel external health care providers and community members now better understand each other | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| 11% | 11% | 78% | |

| The Naotkamegwanning journey mapping process was effective to create a care pathway for palliative care | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| 0% | 0% | 100% | |

| I recommend that other First Nations communities do a journey mapping exercise to improve palliative care in their community | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| 0% | 0% | 100% |

“Disagree” = disagree + strongly disagree. None (0%) of the survey respondents selected strongly disagree for any statements 1 to 14.

“Agree” = agree + strongly agree.

Service delivery–related outcomes

All respondents (100%) agreed that conducting the journey mapping had the following benefits: helped me better understand the policies and procedures (mandates) of the other organizations involved, identified gaps and problems in service delivery, and was effective to create a care pathway for palliative care. Furthermore, most agreed or strongly agreed that the workshops identified new strategies to improve communication, coordination, and integration of care delivery; generated commitment to solve service delivery issues for residents of Naotkamegwanning; and will help to improve care delivery for Naotkamegwanning residents who are in the last year of life.

Relationship building outcomes

Most respondents agreed that external health care providers and community members now better understand each other, better understand the needs and preferences of clients in Naotkamegwanning, better understand the roles of the other care providers involved, and look at their work in a different way than before.

Other perceived benefits emerged from the analysis of the open-ended survey questions as indicated by the following theme.

Journey mapping increased communication and established partnerships

Survey respondents indicated that the journey mapping workshops led to increased communication and established partnerships among community members and internal and external health care providers. When asked what the most significant outcome of the journey mapping was, respondents indicated that increased communication between the community and health care providers was achieved. For example,

[The most valuable aspect of participating in the journey mapping was] meeting the community members and learning the intricacies of service provision in the area, as well as learning how providers can work together in more coordinated care to deliver services in rural First Nations communities. (External Partner Survey Respondent)

One respondent stated that there was an “increased awareness of the need to facilitate (help promote) communication between organizations and the community.”

Respondents indicated that the use of telemedicine technology was a facilitator to journey mapping as it increased communication between the participants from Naotkamegwanning/Kenora and those in Thunder Bay during the third workshop which took place in Kenora (many of the Thunder Bay–based participants were unable to attend in person due to travel time and cost).

Was the journey mapping process and the resultant care pathway perceived to improve quality, access, and integration of health services for palliative care clients?

Workshop data findings

During Workshop 5, it was revealed that all steps in the care pathway were being followed (Table 3), suggesting that the care pathway is being implemented as intended and that the pathway is effective in integrating services. Although areas for improvement in the care pathway were identified, participants perceived the process to have improved quality, access, and integration of services. Quality improvement will be ongoing, and the care pathway revisited on an ongoing basis as the individuals involved in the care path change. The following excerpt from the workshop report illustrates the effectiveness of the process:

What was quite evident and encouraging was the obvious commitment of the partners to finding solutions to identified problems; the process of developing the care path has in itself fostered relationships, increased communication; and thereby improved care. There seemed to be general agreement that although a lot of work remains to be done, the care path and the Wiisokotaatiwin program in general have benefitted community members who are very ill and their families. (EOLFN Community Consultant)

Survey findings

As can be seen in Table 5, there was a high level of agreement on the rating scale items related to outcomes. When asked how effective the journey mapping workshops were in creating a care pathway for Naotkamegwanning clients in need of palliative care, respondents stated that the goals (creation of a care pathway) were achieved. All respondents (100%) recommended that other First Nations communities do a journey mapping exercise to improve palliative care in their community.

The following theme, which emerged from the open-ended questions, is also related to the perceived impact of journey mapping.

Journey mapping is recommended to create a care pathway

Survey respondents agreed that they would recommend journey mapping to create a care pathway for First Nations community members who could benefit by palliative care. Survey respondents also had suggestions on how to improve the journey mapping process for future use.

When asked what the most significant change or outcome of the journey mapping was, a respondent indicated that “a care path was actually developed which will benefit the community, and we had the opportunity to study the process and make recommendations on the process for other communities.”

When asked “How effective were the journey mapping workshops in creating a care pathway for Naotkamegwanning clients in need of palliative care?” most respondents stated that the journey mapping workshops were “very effective” in creating the care pathway. Some respondents offered additional comments stating that “we floundered a bit with process, but I think the key in creating the care pathway is to get all the players together and committed, and the workshops certainly accomplished that.” Another respondent stated that “we needed to change the facilitation strategy to better engage the community members more quickly.”

Survey respondents agreed that the value stream mapping process used in Workshop 2 was not successful nor was the facilitation style. Value stream mapping was identified as both a barrier and the least valuable aspect of participating in the journey mapping workshops. Respondents felt that value stream mapping disengaged community members and was intimidating to them. They also felt that a “fancy process” was not needed, and a respondent indicated to “keep it [journey mapping] simple.”

When asked what suggestions they had for First Nations communities that conduct journey mapping workshops in the future, one respondent summarized, by stating that

I would strongly recommend journey mapping workshops as the most effective way of developing a care path, which for all intents and purposes, is the [palliative care] program; you need a good facilitator for the workshops who understands health care and the community, but no need for processes—keep it simple: “what happens now?” “What do we want to happen?” “What do we need to do to make that happen?”

Discussion

The purpose of this article was to describe and analyze the journey mapping strategy used by Naotkamegwanning First Nation to create their palliative care pathway. Over a period of 2 years in Naotkamegwanning, by implementing the principles of PAR and an Indigenous paradigm, an effective methodology for conducting journey mapping gradually evolved. Naotkamegwanning community members, the researchers, and internal and external heath care providers perceived journey mapping as an effective tool to create the care pathway. Having the care pathway developed helped to integrate the services of internal and external health care providers with the community’s cultural practices. The journey mapping process was also seen as contributing to improved client care in Naotkamegwanning.

Before discussing the implications of these findings, some study limitations are acknowledged. First, the research methodology was chosen to generate new knowledge through an in-depth analysis of the experience of one community (case study method) as opposed to other methods that intend generalizability. The findings presented in Figure 4 now offer a promising practice to guide other communities in developing their palliative care pathways. Broad applicability of findings must be evaluated through future research implementing our detailed journey mapping toolkit (http://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/1-Example-EOLFN-Journey-Mapping-Guide.pdf) in other contexts. There is intentional unoccupied space in the wingspan of the eagle to symbolize opportunity for future research and evolution of this figure. Second, for future journey mapping, time is required (likely 2 years) for relationship building and ensuring a process that respects community control, scheduling, and pacing of workshops.

Despite these limitations, this research makes important contributions to the literature on journey mapping and palliative care development in First Nations communities and suggests implications for policy and practice. This research contributes a detailed analysis of the journey mapping process as well as the application of journey mapping to develop palliative care programs; we are unaware of similar work in Canada or internationally on the use of journey mapping to develop palliative care.

The results of this research suggest that journey mapping is an effective process to create a palliative care pathway for First Nations communities, and that it can contribute to service integration. This research also provides many valuable lessons learned and promising practices related to conducting journey mapping to design a palliative care pathway in a First Nations community. The implications of these findings for policy, practice, and future research are discussed below.

Implications for policy

This case study contributes to the literature related to journey mapping to create a palliative care pathway in First Nations communities and how the journey mapping process could be conducted in the future. Specifically, it provides new knowledge of how to create a palliative care pathway for providing culturally appropriate palliative home care in First Nations communities through integration of federal and provincial health services. Also, the EOLFN capacity development model that guided the community capacity development was validated as a theory of change to guide the process.3 One unique feature of the integration process is that the First Nations community initiated the integration and controlled it, letting the external providers know how they needed to assist/support.

This work was done in the absence of a guiding policy framework. Thus, the findings also provide guidance for creation of new policy based on community capacity development in First Nations communities and creating regional health services partnerships to overcome jurisdictional barriers and provide culturally appropriate palliative care. In terms of implementing the care pathway, it is important to acknowledge the additional government pilot funding that was obtained to enhance service delivery for the Wiisokotaatiwin Program.44 The care pathway could not have been implemented without this enhanced funding.

The findings also illustrate the relevance of the emerging public health approach as a policy paradigm for developing palliative care in First Nations communities with the focus on creating partnerships, making a practical difference, individual leaning and personal growth, and developing community capacity.32 A public health approach is an appropriate policy paradigm to address the palliative care needs of First Nations communities as it includes community development as a primary strategy and acknowledges the need to address the social determinants of health. This case study has presented journey mapping as a strategy that can support First Nations people to receive palliative care at home if that is their choice. Journey mapping could also further reduce costs and burden to the health care system by allowing First Nations people to receive palliative care services in their home communities and avoid unnecessary transfers to acute care that uproot them and their families from their community and culture.

Implications for practice

The learnings that emerged from this case study offer the following lessons learned and promising practices that may guide other First Nations communities in implementing journey mapping to develop a palliative care pathway.

Community controlled and community paced

Successful journey mapping is community controlled and community paced from the onset. The Leadership Team planned and implemented the journey mapping process with support from the researchers. The overall process may take 2 years. General community members are kept involved and informed by the Leadership Team. There was also a well-attended meeting open to all the members of the community at the beginning and end of the EOLFN project where the advisory committee and researchers answered questions.

Contribution of stakeholders was essential

Face-to-face stakeholder commitment for long-term involvement was essential in the journey mapping process and creation of the palliative care pathway. Planning by the Leadership Team determined which stakeholders were most relevant to include in journey mapping before the first workshop. All stakeholders invited were involved in providing services to people living in Naotkamegwanning and were personally motivated to improve quality of service. There was a high level of retention of the stakeholders over the 2-year period, with only a few unavoidable changes due to retirement, illness, or maternity leave.

Each stakeholder had an important role in the journey mapping workshops, and they were all essential for moving forward the process and creation of that care pathway. To implement the care pathway and provide services to the community members in the proposed new way, stakeholder commitment needed to continue after the journey mapping workshops were complete. In addition, this involvement needs to be supported by the stakeholders’ organization (ie, participation requires a major commitment of time and sometimes telemedicine or travel costs).

Value stream mapping is not recommended

The standard value stream mapping approach as commonly used in quality improvement in health services did not enhance the journey mapping experience or facilitate the creation of the palliative care pathway. In fact, this approach was a barrier. The value stream mapping workshop facilitation style and lean terminology was introduced because it is familiar to most health care providers and a key tool used in their own settings. However, the approach proved unfamiliar to community members and did not resonate with them. Thus the journey mapping approach needed to be adapted from value stream mapping to be more consistent with the Indigenous paradigm. Therefore, the value stream mapping approach is not recommended for use in other First Nations communities. Applying the guiding principles of the Indigenous paradigm45–48 is more appropriate.

Workshop facilitators must be responsive, and continually monitor the audience

Workshop facilitators play a key role during the journey mapping workshops, because they must be aware of what the audience is telling them and also pay attention to nonverbal information. The lesson learned is that when the facilitator is not from the community, or is from a different cultural background, they must familiarize themselves and be aware of cues that indicate lack of interest, disagreement, or frustration in participants. These cues can vary culturally between First Nations participants and external health care professionals. For example, during Workshop 2, First Nations community members and Elders disengaged and did not participate until the original structured format of the workshop was abandoned and revised to be more appropriate for culture and context. Furthermore, the focus group findings indicated that community members felt intimidated and at times felt as though they were not listened to by the health care providers. Yet, the health care providers did not perceive this; they perceived that the community voice was being heard.

The differing expectations and opinions between community members and health care providers are lessons learned for future facilitation and stakeholders. The facilitator and other stakeholders must all work to ensure that everyone gets a chance to participate and that all stakeholders are listened to. Where possible, the facilitator should be an Indigenous person, or co-facilitators can include 1 member of the community and 1 external person. When necessary, the workshop facilitator should engage Elders or community members by asking “what do you think?” to facilitate participation. Having a cultural guide such as an Elder in the workshop to consult and support also assists the facilitator. This promising practice ensures that all voices are heard, avoids disempowerment, and ensures that power and control are community driven and focused.

In addition, attention needs to be paid to terminology. Initially, there was not enough Elder and community support for journey mapping. However, when the term Wiisokotaatiwin began being used (as opposed to palliative care or dying), Elders and community members started to understand the vision and goal of the work being done and became more engaged. Strong internal community leadership was key. The need to change terminology to be culturally and community appropriate was one of the issues identified during the journey mapping process and rectified.

Journey mapping improved communication, improved service integration, and enhanced services

One of the most significant barriers to service integration and care delivery related to communication problems between organizations and providers (eg, use of consent forms, documentation lacking or not shared). During the journey mapping workshops, stakeholders collaborated on many initiatives for improving communication. The improved collaboration and improved communication translated into better service integration and enhanced services for the clients.

Journey mapping integrated the expectations of the community and the health care providers

The journey mapping process provided an environment (time, place) and strategy for promoting mutual understanding between the community and the external health care providers. During the journey mapping, it became clear that 2 distinct worldviews and their related expectations existed pertaining to providing and receiving palliative care.

Implications for future research

An important contribution of this research is an illustration of the importance of using an Indigenous paradigm. The Indigenous paradigm provided an appropriate foundation to investigate this case study using a PAR methodology. In terms of future research, this research used a case study design and offers emerging lessons learned and promising practices that need to be replicated more broadly in other communities. In addition, further research is needed to assess the long-term benefits and potential unintended impacts of the journey mapping.

Conclusions

This case study presented a unique journey mapping process (adapted from value stream mapping to be more culturally appropriate) that was undertaken to improve access to and integration of local and regional health services to provide culturally appropriate palliative home care in Naotkamegwanning First Nation (in rural Ontario, Canada). The article presented data on how to implement journey mapping for service integration as well as data on the perceived benefits and outcomes of journey mapping as an integration strategy. Lessons learned and promising practices were also offered. It is concluded that journey mapping improves service integration and is a promising practice for other First Nations communities looking to develop an integrated palliative care pathway. The details presented here (about journey mapping processes and outcomes) have relevance to assist Indigenous communities in Canada and internationally.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Naotkamegwanning Leadership Team members. They acknowledge the First Nations community owns the knowledge created, and thank the community for allowing them to share it internationally. They also thank the Wiisokotaatiwin Program partners who participated in the journey mapping workshops.

Footnotes

Peer Review:Two peer reviewers contributed to the peer review report. Reviewers’ reports totaled 284 words, excluding any confidential comments to the academic editor.

Funding:The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant #105885). C.J.M.’s participation was partially supported by the Canada Research Chairs Program.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: JK, MLK, MC, and HP conceived and designed the research. JK and MLK analyzed the data. JK and SN wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JK, MLK, and SN contributed to the writing of the manuscript and jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper. JK, MLK, SN, MC, HP, ECW, and CJM agree with manuscript results and conclusions, made critical revisions, and approved final version. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1. Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association. A Model to Guide Hospice Palliative Care: Based on National Principles and Norms of Practice. http://www.chpca.net/media/319547/norms-of-practice-eng-web.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed February 18, 2017.

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Definition of Palliative Care. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Published 2015. Accessed March 1, 2017.

- 3. Improving End-of-Life Care First Nations Communities Research Team (EOLFN). Developing Palliative Care Programs in First Nations Communities: A Workbook (Version 1) Journey Mapping Guide (e-Book). http://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Palliative-Care-Workbook-Final-December-17.pdf

- 4. Kelley AS, Meier DE. Palliative care: a shifting paradigm. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:781–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aiken LS, Butner J, Lockhart CA, Volk-Craft BE, Hamilton G, Williams FG. Outcome evaluation of a randomized trial of the PhoenixCare intervention: program of case management and coordinated care for the seriously chronically ill. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:111–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association. The Way Forward National Framework: A Roadmap for an Integrated Palliative Approach to Care. http://www.hpcintegration.ca/media/60044/TWF-framework-doc-Eng-2015-final-April1.pdf. Accessed February 27, 2017.

- 8. Connor SR, Pyenson B, Fitch K, Spence C, Iwasaki K. Comparing hospice and nonhospice patient survival among patients who die within a three-year window. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brumley R, Endguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:993–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in Elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association. The Pan-Canadian Gold Standard for Palliative Home Care: Towards Equitable Access to High Quality Hospice Palliative and End-of-Life Care at Home. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association; http://www.chpca.net/media/7652/Gold_Standards_Palliative_Home_Care.pdf. Published 2006. Accessed March 1, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13. First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC). First Nations Regional Longitudinal Health Survey (RHS) 2002/2003: Results for Adults, Youth and Children Living in First Nations Communities. Ottawa, ON: First Nations Centre. First Nations Information Governance Centre; https://fnigc.ca/sites/default/files/ENpdf/RHS_2002/rhs2002-03-the_peoples_report_afn.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed April 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14. First Nations Information Governance Centre. First Nations Regional Health Survey (RHS) 2008/10: national report on adults, youth and children living in First Nations communities. http://fnigc.ca/sites/default/files/FirstNationsRegionalHealthSurvey(RHS)2008-10-NationalReport.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed February 22, 2017.

- 15. Government of Canada, Indigenous and Northern Affairs (Internet). First Nations People in Canada. https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng.

- 16. Prince H, Mushquash C, Kelley ML. Improving end-of-life care in First Nations communities: outcomes of a Participatory Action Research Project. Psynopsis. 2016:17–19. http://www.cpa.ca/docs/File/Psynopsis/fall2016/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hotson KE, Macdonald SM, Martin BD. Understanding death and dying in select first nations communities in northern Manitoba: issues of culture and remote service delivery in palliative care. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2004;63:25–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gorospe EC. Establishing palliative care for American Indians as a public health agenda. Internet J Pain Symptom Contr Palliative Care. 2006:4 https://ispub.com/IJPSP/4/2/8930. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kitzes J, Berger L. End-of-life issues for American Indians/Alaska Natives: insights from one Indian Health Service area. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:830–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lemchuck-Favel L, Jock R. Aboriginal health systems in Canada: nine case studies. J Aborigin Health. 2004;4:28–51. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nova Scotia Aboriginal Home Care Steering Committee. Aboriginal Long Term Care in Nova Scotia: Aboriginal Transition Fund Home Care on-Reserves Project. Halifax, NS. http://novascotia.ca/dhw/ccs/documents/Aboriginal-Long-Term-Care-in-Nova-Scotia.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed March 13, 2017.

- 22. Kaufert JM, O’Neil JD. Cultural mediation of dying and grieving among Native Canadian patients in urban hospitals. In: De Spelder LA, Strickland AL. eds. The Path Ahead: Readings in Death and Dying. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company; 1989:59–75. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kelly L, Minty A. End-of-life issues for aboriginal patients. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53:1459–1465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Castleden H, Crooks VA, Hanlon N, Schuurman N. Providers’ perceptions of Aboriginal Palliative Care in British Columbia’s rural interior. Health Soc Care Community. 2010;18:483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ellerby JH, McKenzie J, McKay S, Gariepy GJ, Kaufert JM. Bioethics for clinicians: 18. Aboriginal cultures. Can Med Assoc J. 2000;163:845–850. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Habjan S, Prince H, Kelley ML. Caregiving for Elders in first nations communities: social system perspective on barriers and challenges. Can J Aging. 2012;31:209–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Paz-Ruiz S, Gomez-Batiste X, Espinosa J, Porta-Sales J, Esperalba J. The costs and savings of a regional public palliative care program: the Catalan experience at 18 years. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. O’Brien AP, Bloomer MJ, McGrath P, et al. Considering aboriginal palliative care models: the challenges for mainstream services. Rural Remote Health. 2013;13:2339 http://www.rrh.org.au/articles/subviewnew.asp?ArticleID=2339. Accessed March 28, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. World Health Organization. Cancer Pain Relief and Palliative Care (Technical report series 804). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1990. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/trs/WHO_TRS_804.pdf. Accessed March 28, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stjernsward J. Palliative care: the public health strategy. J Public Health Policy. 2007;28:42–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Karapliagkou A, Kellehear A. Public health approaches to end of life care: a toolkit. Public Health England and National Council for Palliative Care. http://www.ncpc.org.uk/sites/default/files/Public_Health_Approaches_To_End_of_Life_Care_Toolkit_WEB.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed April 1, 2017.

- 32. Sallnow L, Richardson H, Marrya SA, Kellehear A. The impact of a new public health approach to end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2016;30:200–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Abel J, Walter T, Carey LB, et al. Circles of care: should community development redefine the practice of palliative care? BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3:383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kellehear A. Compassionate Cities: Public Health and End-of-Life Care. London, England and New York, NY: Routledge; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kelley ML. Guest editorial: an indigenous issue: why now? J Palliat Care. 2010;26:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hampton M, Baydala A, Bourassa C, et al. Completing the circle: Elders speak about end-of- life care with Aboriginal families in Canada. J Palliat Care. 2010;26:6–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hordyk SR, Macdonald ME, Brassard P. End-of-life care in Nunavik, Quebec: Inuit experiences, current realities, and ways forward. J Palliat Med. 2017;20:647–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rosenberg J, Mills J, Rumbold B. Putting the public into public health: community engagement in palliative and end of life care. Progr Palliat Care. 2016;24:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lewin K. Action research and minority issues. J Soc Issue. 1946;2:34–46. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kemmis S, McTaggart R. Participatory action research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. Handbook of Qualitative Research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2005:559–603. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fruch V, Monture L, Prince H, Kelley ML. Coming home to die: six nations of the Grand River Territory develops community-based PC. Int J Indigen Health. 2016;11:50–74. [Google Scholar]

- 42. EOLFN Research Team A Framework to Guide Policy and Program Development for Palliative Care in First Nations Communities. http://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca/wpcontent/uploads/2015/01/Framework_to_Guide_Policy_and_Program_Development_for_PC_in_FN_Communities_January_16_FINAL.pdf38. Published 2015. Accessed April 2, 2017.

- 43. EOLFN Research Team. Naotkamegwanning First Nation community needs assessment report. Final report. http://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca/wpcontent/uploads/2013/01/NFN_CommunityNeedsAssessment_Report_August2013_wo_RECs.pdf. Published 2008. Accessed March 31, 2017.

- 44. Nadin S, Kelley ML, Prince H, Crow M. An Evaluation of Naotkamegwanning First Nation’s Wiisokotaatiwin Pilot Program. Final report. http://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca/wpcontent/uploads/2016/01/Naotkamegwanning_Wiisokotaatiwin_Program_Evaluation_EOLFN_FINAL-Revised-Dec12-16.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed April 2, 2017.

- 45. Atkinson J. Privileging indigenous research methodologies. Paper presented at the Indigenous Voices Conference; Carins, QLD; October, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kovach M. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations and Contexts. Toronto, ON; Buffalo, NY: University of Toronto Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wilson S. What is an Indigenous research methodology? Can J Nat Educ. 2001;25:175–179. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wilson S. Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Black Point, NS: Fernwood Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bartlett C, Marshall M, Marshall A. Two-eyed seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together Indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. J Environ Stud Sci. 2012;2:331–340. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stake RE. Case studies. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 1998:346. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lord J. A Quick Guide to Customer Journey Mapping (E-book). http://bigdoor.com/blog/2013/11/01/a-quick-guide-to-customer-journey-mapping/. Published 2013.

- 52. Richardson A. Understanding Customer Experience (E-book). https://hbr.org/2010/10/understanding-customer-experie. Published 2010.

- 53. Rother M, Shook J. Learning to See: Value Stream Mapping to Add Value and Eliminate Muda. 1.3 ed. Cambridge, MA: Productivity Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Baudin M. Where do “value stream maps” come from? (Web log article). http://michelbaudin.com/2013/10/25/where-do-value-stream-maps-come-from/. Published 2013. Accessed March 2, 2017.

- 55. Ben-Tovim DI, Bassham JE, Bolch D, Martin MA, Dougherty M, Szwarcbord M. Lean thinking across a hospital: redesigning care at the Flinders Medical Centre. Aust Health Rev. 2007;31:10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Poksinska B. The current state of Lean implementation in health care. Qual Manage Health Care. 2010;19:319–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Koski J. A Case Study of Journey Mapping to Create a Palliative Care Pathway for Naotkamegwanning First Nation: An Analysis and Lessons Learned Using Participatory Action Research [unpublished master’s thesis]. Thunder Bay, ON: Lakehead University; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Improving End-of-Life Care First Nations Communities Research Team (EOLFN). Developing PC Programs in First Nations Communities: A Workbook (Version 1). Journey Mapping Guide. http://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/1-Example-EOLFN-Journey-Mapping-Guide.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2017.

- 59.Netaawgonebiik Health Services Home & Community Care and Long-Term Care. Wiisokotaatiwin Program Guidelines. http://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/4-Example-NFN-Wiisokotaatiwin-Program-Guidelines-Booklet.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2017.

- 60. Thorne S, Kirkham SR, O’Flynn-Magee K. The analytic challenge in interpretive description. Int J Qual Method. 2004:3 https://sites.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/3_1/pdf/thorneetal.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 61. MacPherson I, McKie L. Qualitative research in programme evaluation. In: Bourgeault IL, Dingwall R, De Vries RG. eds. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Methods in Health Research. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE; 2010:454–478. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cresswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation Checklist. https://wmich.edu/sites/default/files/attachments/u350/2014/qualitativeevalchecklist.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2017.