Highlights

-

•

75% of pancreas transplantation is SPKT.

-

•

The optimal surgical management for graft perforation is still unknown.

-

•

Delayed graft duodenal perforation is very rare.

-

•

The omega loop may contribute to increased pressure by luminal congestion.

-

•

When delayed duodenal graft perforation occurs, graft excision may not be necessary.

Keywords: Pancreas transplantation, Delayed duodenal graft perforation, Chronic rejection, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Pancreas transplantation is the best treatment option in selected patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Here we report a patient with a nonmarginal duodenal perforation five years after a simultaneous pancreas-living donor kidney transplantation (SPLKT).

Presentation of case

A 31-year old male who underwent SPLKT five years previously presented with severe abdominal pain. He had a marginal duodenal perforation four years later, treated by primary closure and drainage. Biopsy of the pancreas and duodenum graft at that time showed chronic rejection in the pancreas and acute inflammation with an ulcer in the duodenum. At presentation, computerized tomography scan showed mesenteric pneumatosis with enteric leak and ileal dilatation proximal to the anastomotic site. We performed emergent laparotomy and found a 1.0 cm perforation at the nonmarginal, posterior wall of the duodenum. Undigested fiber-rich food was extracted from the site and an omental patch placed over the perforation. An ileostomy was created proximal to the omega loop for decompression and a drain placed nearby. The postoperative course was unremarkable.

Discussion

There are only eight previous cases of graft duodenal perforation in the literature. Fiber-rich food residue passing through the anastomosis with impaction may have led to this perforation.

Conclusion

When a patient is stable, even in the presence of delayed duodenal graft perforation, graft excision may not be necessary. Intraoperative exploration should include Doppler ultrasound examination of the vasculature to rule out thrombosis as a contributor to ischemia. Tissue biopsy should be performed to diagnose rejection.

1. Introduction

Pancreas transplantation is the optimal treatment for selected patients with Type 1 diabetes mellitus. According to the International Pancreas Transplant Registry (IPTR), of more than 35,000 pancreas transplantations reported by the end of 2010, approximately 75% were simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantations, 18% were pancreas after kidney transplantation, and 7% were pancreas transplantation alone [1]. With advances in surgical technique, immunosuppression, management of graft rejection, and other related complications, the reported 10-year and 20-year patient survival rates were 63% and 36%, respectively [2]. The surgical complication rate is reported as 22% including graft pancreatitis, infection/abscess, necrosis, graft-vessel thrombosis, anastomotic leak, and intraabdominal hemorrhage [3]. Although most complications occur within 60 days of transplantation, delayed graft duodenal perforation is very rare.

This work has been reported in accordance with the SCARE criteria [4].

2. Presentation of case

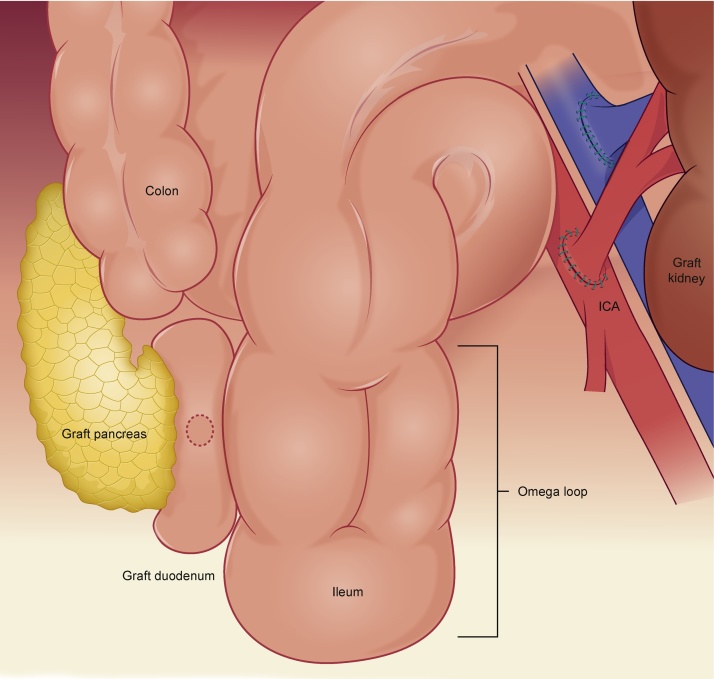

A 31-year old male five years status-post simultaneous pancreas-living donor kidney transplantation (SPLKT) presented with severe abdominal pain. He developed type 1 diabetes mellitus at the age of 8 years and was treated with peritoneal dialysis since age 25. His past surgical history includes SPLKT initially with bladder drainage, then converted to enteric drainage one year later due to recurrent urinary tract infections. At that time, a side-to-side duodeno-ileostomy was performed and an omega loop created to minimize reflux. After SPLKT he was free from peritoneal dialysis and insulin therapy, which preopertaively included approximately 30 U of long acting insulin daily. He had a marginal duodenal perforation four years later, treated by primary closure and drainage. Biopsy of the graft showed chronic rejection in the pancreas and acute inflammation with ulcer in the duodenum. The maintenance trough level of Tacrolimus was increased from 5 ng/ml to 10 ng/ml postoperatively and remained stable. Current medications include tacrolimus 1.5 mg, mycophnolic acid 360 mg, esomeprazol, clopidgrel, carvedilol, simbastatin/ezetimibe, and allopurinol.

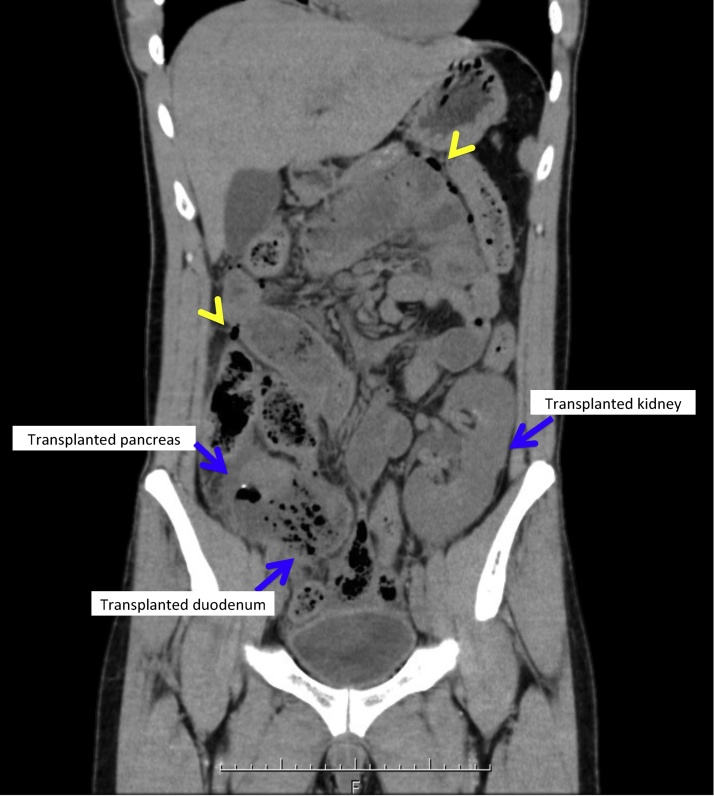

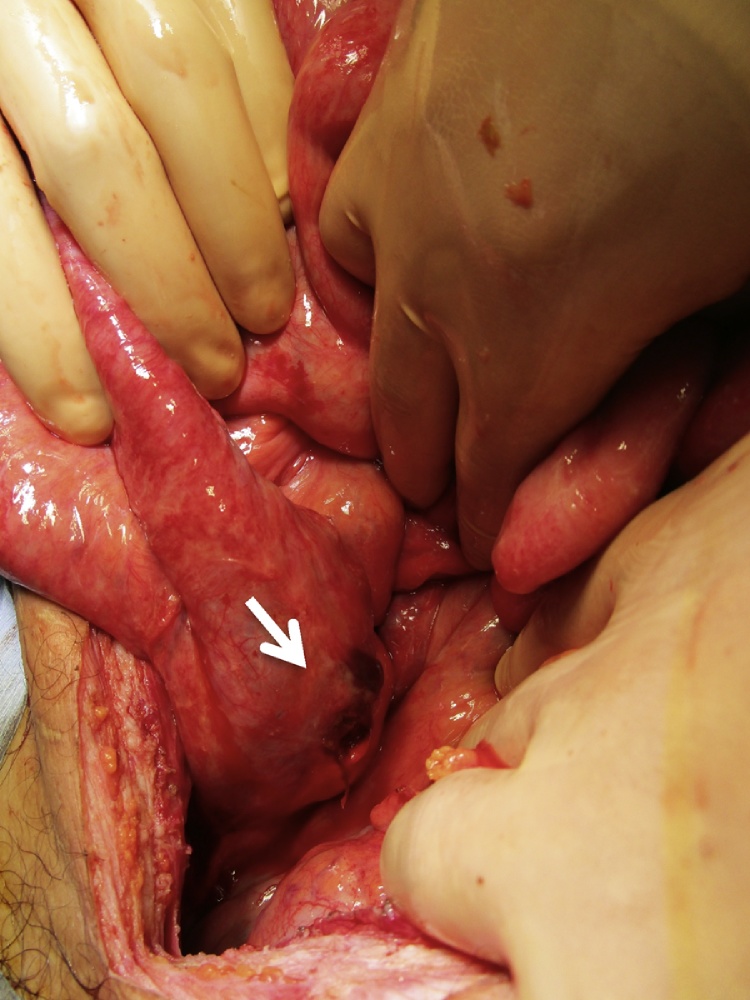

At presentation, physical examination of the abdomen showed generalized tenderness with guarding and rebound. Laboratory studies showed elevated lipase and creatinine levels at 377 U/L and 1.16 mg/dl, respectively. The trough level of tacrolimus was within the optimal range at 6.5 ng/ml. Cytomegalovirus antigen was not detected. A computed tomography scan showed mesenteric pneumatosis intestinalis with enteric leak and ileal dilatation proximal to the anastomotic site including the omega loop [Fig. 1]. Given the findings, we proceeded with exploration. Operative findings included a 1.0 cm perforation in the posterior wall of the graft duodenum [Fig. 2, Fig. 3]. There were a few intraabdominal adhesions. The distance between the enteric anastomosis to the ileocecal valve was approximately 40 cm. Undigested fiber-rich food was extracted from the site and an omental patch placed over the perforation. An ileostomy was created proximal to the omega loop for decompression and a drain placed nearby. The postoperative course was unremarkable. Stoma closure was performed four months later and he has been well using the same immunosuppressant regimen.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography scan of the abdomen shows free air (arrow head) and the graft duodenum impacted with food.

Fig. 2.

Perforation of the posterior wall of the graft duodenum.

Fig. 3.

A schematic drawing.

3. Discussion

Most pancreas transplantation procedures are performed with systemic venous delivery of insulin and either bladder (systemic-bladder) or enteric (systemic-enteric) drainage of the exocrine secretions. The primary surgeon chose systemic venous-bladder drainage initially that allowed measurement of urinary amylase as a marker for graft rejection. The chronic loss of pancreatic secretions can result in dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, local bladder irritation and allograft pancreatitis [5]. The need for conversion to enteric drainage has been reported to be 20%–30% as for this patient [6]. At the second operation, a side-to-side duodeno- ileostomy was performed at 40 cm from ileocecal valve, with an omega loop created to minimize reflux. A Roux-en-Y configuration was not chosen due to the anatomical difficulties associated.

The optimal configuration of anastomosis is unknown. In International Pancreas Transplant Registry analyses, no differences were reported in short-term outcomes according to surgical technique (bladder versus enteric exocrine drainage, Roux limb versus no Roux limb, systemic versus portal venous delivery of insulin) [7]. The optimal configuration varies depending on the surgeons’ experiences and preferences. To avoid increased luminal pressure by food residue, a Roux-en Y configuration may have had an advantage in this case.

There are eight previous cases of graft duodenal perforation reported in the literature [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. The causes of perforation include rejection, cytomegalovirus duodenitis, simple ulcer, bowel ischemia at the anastomotic margin, and internal hernia. Three of the eight cases eventually required graft pancreatectomy. Two of them required graft excision due to repeated perforation after drainage was attempted initially, and one due to graft failure by severe systemic infection including cytomegalvirus. The optimal surgical management for graft perforation is still unknown. Successful management includes direct closure with or without omentopexy, graft duodenectomy graft pancreatectomy, and omentopexy with diverting ileostomy, as in the present patient. Subsequent procedures, intended for preventing recurrence such as converting to other configurations, e.g Roux-en-Y configuration for enteric anastomosis, are not reported.

In this patient, during the abdominal exploration, the abdominal fossa was clean without adhesions despite two previous operations. Perker et al. investigated the influence of common immunosuppressive drugs on adhesion formation after abdominal surgery in an experimental rat model [15]. Laparotomy was made and cecum was exteriorized and abraded. Rats were randomized to be treated with either systemic immunosuppressive agents such as mycophnolate mofetil, tacrolimus, or cyclosporine, or agents directly placed into the peritoneal cavity. Fourteen days later at repeat laparotomy, they found significantly less adhesions in the intraperitoneal mycophnolate mofetil, systemic mycophenoate mofetil and intraperitoneal cyclosporine groups. Formerly, tacrolimus has reduced peritoneal adhesions in a bowel transplantation model in rats [16]. The medications of this patient included mycophnolic acid and tacrolimus with optimal range. Immunosuppresive agents might play a role in preventing postoperative peritoneal adhesions.

The exact cause of perforation is unknown, in part because no tissue nor Doppler ultrasound was examined. The elevated lipase level may be a result of chronic rejection but can be considered also as a consequence of perforation. Due to the fact that the postoperative course was unremarkable without changing the immunosuppression regimen, we believe that fiber-rich food residue passing through the anastomosis with impaction may have led to this perforation. The omega loop may contribute to increased pressure in the graft duodenum by luminal congestion. Patients suspected to have chronic rejection, may need modification of their diet. At last, it was ideal that a tissue biopsy had been taken at operation to differentiate cytomegalovirus infection and chronic rejection, which had completely different treatment.

4. Conclusion

As general surgeons caring for an increasing number of post-transplant patients, it is important to be familiar with the anatomy of this procedure, as well as the complications and their management. When a patient is stable, even in the case of delayed duodenal graft perforation, graft excision may not be necessary. Intraoperative exploration should include Doppler ultrasound examination of the vasculature to rule out thrombosis as a contributor to ischemia. Tissue biopsy should be performed to diagnose rejection.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflict of interest to be declared.

Sources of funding

No source to be stated.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent

Informed consent for the publication of this work has been taken by the patient.

Author contribution

Taizo Sakata: operated the patient and wrote the manuscript.

Hideki Katagiri: surgeon operated the patient.

Tadao Kubota: surgeon responsible for the in-patient optimizaiton and reviewed the manuscript.

Takashi Sakamoto and Kentaro Yoshikawa: surgeons who provided clinical care of the patient during his treatment.

Toru Kojima: reviewed the manuscript.

Alan Kawarai Lefor: reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Cheol Wonng Jung: One of the primary surgeons who follows this patient at outpatient clinic.

Guarantor

Taizo Sakata.

References

- 1.Gruessner A.C. Update on pancreas transplantation: comprehensive trend analysis of 25,000 cases followed up over the course of twenty-four years at the International Pancreas Transplant Registry (IPTR) Rev. Diabet. Stud. 2011;8:6–16. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2011.8.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sollinger H.W., Odorico J.S., Becker Y.T., D’Alessandro A.M., Pirsch J.D. One thousand simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants at a single center with 22-year follow-up. Ann. Surg. 2009;250:618–630. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b76d2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grochowiecki T., Gałązka Z., Madej K. Surgical complications related to transplanted pancreas after simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2014;46:2818–2821. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sollinger H.W., Messing E.M., Eckhoff D.E. Urological complications in 210 consecutive simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants with bladder drainage. Ann. Surg. 1993;218:561–570. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199310000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Del Pizzo J.J., Jacobs S.C., Bartlett S.T., Sklar G.N. Urological complications of bladder-drained pancreatic allografts. Br. J. Urol. 1998;228:284–296. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gruessner A.C., Sutherland D.E.R. Pancreas transplant outcomes for United States (US) and non-US cases as reported to the United Netwerk for Orgn Sharing (UOS) and the International Pancreas Transplant Registry (IPTR) as of May 2003. In: Cecka J.M., Terasaki P.I., editors. Clinical Transplants 2003. UCLS immunogenetics Center; Los Angeles, Calif: 2004. 3:21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gruessner R.W., Manivel C., Dunn D.L., Sutherland D.E. Pancreaticoduodenal transplantation with enteric drainage following native total pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis: a case report. Pancreas. 1991;6:479–488. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199107000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schleibner S., Theodorakis J., Illner W.D., Leitl F., Abendroth D., Land W. Ulcer perforation in the grafted duodenal segment following pancreatic transplantation—a case report. Transplant. Proc. 1992;24:827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stephanian E., Gruessner R.W., Brayman K.L., Gores P., Dunn D.L., Najarian J.S. Conversion of exocrine secretions from bladder to enteric drainage in recipients of whole pancreticoduodenal transplants. Ann. Surg. 1992;216:663–672. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199212000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esterl R.M., Stratta J.R., Taylor R.J., Radio S.J. Rejection with duodenal rupture after solitary pancreas transplantation: an unusual cause of severe hematuria. Clin. Transplant. 1995;9:155–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee H.K., Chung D.H., Jung J., Kim S.C., Han D.J., Kang K.H. Three cases of pancreas, allograft dysfunction. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2000;15:105–110. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2000.15.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyagi S., Sekiguchi S., Akamatsu Y., Satoh K., Takeda I. Nonmargical-donor duodenal ulcers caused by rejection after simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplantation: a case report. Transplant. Proc. 2011;43:3292–3295. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.09.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takayuki Y., Narumi Shunji, Okada Manabu. Delayed graft duodenal perforation after simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation. Jpn. J. Gastroenterol. Surg. 2015;48(11):929–935. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peker Kemal, Inal Abdullah, Sayar Ilyas. Prevention of intraabcominal adhesions by local and systemic administration of imuunosuppressive drugs. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2013;15(December (12)) doi: 10.5812/ircmj.14148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wasserberg N., Nunoo-Mensah J.W., Ruiz P., Tzakis A.G. The effect of immunosuppression on peritoneal adhesions formation after small bowel transplantation in rats. J. Surg. Res. 2007;141(2):294–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.12.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]